1—

From Private Practice to Public Service

A Parisian Midwife

4—

Hanging Her Shingle:

Paris, 22 February 1740

A clerk inscribes in the register of the Châtelet police court today that Marguerite Le Boursier, mature maiden, is officially received "mistress matron midwife of the city and fauxbourgs of Paris."[1] She is twenty-five years old. Five months ago she completed her three-year apprenticeship with Anne Bairsin, dame Philibert Mangin, and passed her qualifying examinations at the College of Surgery. This was a major expense—169 livres and 26 sous—and involved a hair-raising test administered by a panel composed of the king's first surgeon or his lieutenant, a number of Paris surgeons, various deans of the medical faculty and royal surgical school, the four sworn midwives of Paris attached to the Châtelet, and receivers, provosts, class masters, and council members.[2] An intimidating ordeal, an awesome rite of passage, but she survived it. She had then submitted letters of capacity and mastery of her art with a request to be formally accepted by the city's court.

Before approving her they must get character references as is customary, but they do not hurry. It has taken this long for police officials to organize interviews with her parish priest and various other neighbors and acquaintances. Those questioned might have been shoemakers, goldbeaters, innkeepers, or tailors who lived nearby, or professors of surgery or doctors regent of the medical faculty with whom she had contact. Whoever they were—the records identifying them are not preserved in her case—they responded affirmatively to the rather formulaic questions asked. Just last week, on the seventeenth and nineteenth of February, they gave sworn depositions that Le Boursier upholds the Catholic, apostolic, and Roman religion, lives an upstanding life, and demonstrates fidelity in the service of the king and of the public.[3] Now that a favorable report has come in, she simply needs to "take the oath required in these

cases" to be legally admitted to the ranks of Paris midwives, swearing never to administer an abortive remedy and always to call masters of the art to help in difficult cases.[4] And she must pledge to honor one further obligation.

On the first Monday of every month, if it is not a holiday, all sworn midwives are expected to attend holy services at the church of St. Côme and, afterward, pay "pious and charitable visits" to indigent women still inconvenienced by present or past pregnancies.[5] The church, dedicated to the martyrs Côme and Damien, patron saints of surgery, sits on the corner of rue de la Harpe and rue des Cordeliers on the Left Bank, halfway between the river and the Luxembourg Gardens. Next to the church is a cemetery surrounded by charnel houses, and beyond the cemetery is the school of surgery, familiarly known also as St. Côme. For centuries the sick have flocked here on the first Monday of each month to be tended for free. It is a scene at once morbid and heartening. The cemetery keeps its ditch open until it has received its full complement of corpses; the dead who cannot be accommodated there are buried in the church or surrounding walls. Often the bodies and bones are used in surgical demonstrations. Since 1664 surgeons have been giving lessons to midwives in the charnel house on the western border of the cemetery, which abuts the church, although seven years ago the courses were moved to the college's amphitheater. Over the cemetery's south wall there is a granary and storehouse, where the poor find provisions. They are comforted, once a month, to be in the helping hands of healers.[6]

Le Boursier will become part of this world now. Perhaps she knows it well already, and even as an apprentice has attended courses there with her teacher. What sort of relationship do they have? She never once mentions Anne Bairsin in her textbook or letters. Yet Delacoux reported that her packet of private papers contained several memoirs on extraordinary deliveries and cesarean sections written, "with precision and exactitude," by Bairsin, "which show her to have been a practitioner both able and learned [instruit ]."[7] So Le Boursier held on to these writings by her teacher all her life, valuing them enough to keep them (and keep track of them) throughout all her travels. They may have guided her hand in certain circumstances, or served some more sentimental purpose. Might she have collected other manuscripts or case studies by female colleagues, and saved them too over the years? Such unacknowledged debts are probably nu-

merous, for she begins to hone her skills now as an official member of the group of Paris midwives, busy women with vast experience, sources of much shared wisdom and lore.

Louis Sébastien Mercier, the famous chronicler of Paris, estimates that each of the two hundred or so midwives of the capital delivers about one hundred babies each year.[8] Such an average is misleading; some of these women are surely much more in demand than others. But there is no doubt that, for one with a good reputation, this is a strenuous and full life. Mercier describes the tavaïolle , a large muslin and lace cloth the midwife wraps every baby in, rich or poor, for the trip to church, a kind of "spiritual frock coat that attends all baptisms, the principal and most conspicuous garment of a midwife. If this cloth is not sanctified, then none in the world can be, because this one gets blessed sometimes as often as four times a day." The midwife also uses it to carry the many candies and sugar-coated almonds [dragées ] she receives as tokens of thanks from mothers, fathers, godparents, and guests at each birth, perhaps two to three pounds of these goodies at a time. "The armoire of such a midwife rivals the boutique of a confectioner on the rue des Lombards."[9]

Because he always has an eye for the sensational and scandalous, Mercier stresses another important role that city midwives play. They do not just officiate at family births; many of them help conceal unwed girls in their apartments, and they are as skilled in diplomacy as in delivery. As a result, hardly anyone seeks an abortion. A girl who finds herself pregnant, though she may concoct a story that she's leaving for the country, need only go around the corner or across the street to the local midwife to hide until she gives birth. Total secrecy is maintained in these apartments, which no one can enter without superior orders. They are divided into many discretely curtained partitions. For two or three months the inhabitants of these cells might converse, but they might never see or know one another. In the capital these wayward girls have privacy; while confined they can look out onto the roofs of their unsuspecting parents' home. In country towns, however, there is no such anonymity, and often a great scandal instead. The city midwife takes care of everything, has the baby baptized, gives it to a wet nurse or to the foundling hospital depending on the fortunes and desires of the parents. Midwives charge a lot to provide these services for fugitive

girls (Mercier calls it usury because his sympathies lie with the young lovers, "victims of their sweet weakness"), often as much as twelve livres a day for the room, board, delivery itself, and of course the confidentiality. Justifying the high cost, they remind everyone that their discretion preserves reputations and saves many from utter ruin. The priest, however, knows that if a midwife unaccompanied by a parent presents a baby for baptism, it is a love child born out of wedlock. He is not particularly happy to see her coming alone; bastards deprive him of the customary fee paid for his services by proud mothers and fathers. Anyone who wants to hear anecdotes about the ruses and the courage love inspires (in which the true identities of the adventurers are, of course, never revealed)—such a person need only get to know four or five midwives. They can tell tales for all classes: women of the people, bourgeoises , courtesans, grandes dames .

The truly poor, those with no resources to pay for a private midwife, deliver at the general hospital, the Hôtel Dieu, infamous for its high death rate and its cramming of five or six to a bed in the main wards. But this hospital's separate maternity clinic, the salle des accouchées , is superbly administered; the critical Mercier even goes so far as to say it is "beyond reproach." Thanks to this establishment, and to the public orphanages, the once rampant crime of infanticide is almost unheard of in the capital these days. Delivering in secret and giving the baby to the foundling hospital, however, has become a widespread practice, and the law has looked the other way. Probably only one in a hundred girls who give birth clandestinely even knows that an edict of King Henry II, now fallen into desuetude, once made their action punishable by death.[10]

Le Boursier and her colleagues have numerous other functions besides assisting married women at births and harboring unwed girls during their pregnancies. Juries of midwives are consulted on capital crimes. They are frequently used as expert witnesses in legal battles, sometimes called upon to ascertain whether a woman is a virgin. (Here Le Boursier points out that occasionally the hymen is still intact even if the person in question has "endured [souffert ] the approaches of the male," and is thus "not an absolute proof of her purity," but that in general its presence allows the midwife to "presume advantageously" for the girl.)[11] They are often asked by parties in a legal dispute to establish whether a pregnancy is true or false and make, if necessary, a déclaration de grossesse to a doctor,

surgeon, or directly to police authorities.[12] And their presence is usually requested to determine whether a dead baby expired in the womb or was killed after birth. The famous lung test is used to establish a mother's veracity when accused of infanticide. A baby in the womb does not breathe air, but of course it does once it is born. If a piece of the baby's lung sinks when thrown into water, so the theory goes, it proves that the child never experienced respiration, that it was stillborn. If the piece of lung floats, however, it is because air has gotten into it. "This circumstance would condemn the mother," Le Boursier explains, no matter how much she insists that her child was born dead, being a proof that air penetrated its lung, consequently that it was once, however briefly, alive.[13] The judgments rendered by midwives are regarded as essential, and sometimes even shape the evolving legal system.[14] They are called in on cases of suspected rape, contraceptive use, or abortion. They question seduced and abandoned women during labor, urging them to identify the child's father, thus ensuring the filiation of bastards. Their word is considered sworn testimony. In a very profound sense, then, the law recognizes them and trusts their verdicts. A doctor writing on medical jurisprudence calls their profession "one of the most important in society."[15] Men, in short, often need and depend on their expertise.

Yet for all their importance—indeed, because of it—relations between midwives and authorities, whether religious or secular, have been strained throughout history. These women are powerful; they have special skills, and knowledge of hidden and forbidden mysteries involving conception, blood, death, and passion. Some have practiced illegally and given their profession a bad name, infamous abortionists like Lepère, la Voisin, and Manon, who toward the end of the 1600s were tortured and either burned alive or strangled for their iniquities.[16] This trade is still rife with risks and dangers. Occasionally midwives are blamed for causing the monstrous defects of deformed babies that spew forth into their hands, blamed for somehow conjuring the creatures they merely catch. Even now rumors of sorcery and witchcraft hover around any one of them who behaves bizarrely. Their petty thefts are punished especially severely, as if they, of all people, custodians of the newly born, should know better. One such, "just a poor midwife," accused of stealing copper candlesticks from a wine shop, is whipped and sent for three years

to the prison of the Châtelet, then for longer to the Conciergerie, where she now languishes in chains. Protesting this unduly harsh treatment, she says she is afraid she will die.[17]

Originally the church supervised and controlled midwives, since their work involves them in baptism, in the saving of lives, or at least of souls. An ordinance declared that Protestant women could never exercise this art because they could not be trusted to ondoyer the child, to assure its eternal life if it was dying too fast to get to the priest.[18] Gradually, the secular state has been taking over surveillance of this group, monitoring it closely. Royal edicts in 1664 and 1678, advertised on huge posters, and numerous parlementary injunctions against particular midwives are evidence of the government's seriousness. In 1717 the art of midwifery was declared of the highest value, and dire sentences were announced for those practicing illegally, "read and publicized in loud and intelligible voice with trumpet fanfare" by the king's official criers "in all usual and accustomed places" so no one could claim ignorance of the law.[19] Midwives, then, obviously get a great deal of attention, both good and bad. "The policing of childbirth," says a contemporary, "is an object of the greatest importance in the administration. It interests humanity; upon it depends the health and life of citizens. Abuses that slip in [to this field] are not private misdemeanors; they are public crimes."[20]

Yet Le Boursier and her colleagues, despite efforts to oversee them, continue to function outside the sphere of male control. They gather a loyal clientele without any external help, simply by word of mouth among their female acquaintances. They select apprentices on their own. They are privy to more secrets about lineage and legitimacy than anyone else. It always seems to the authorities that in spite of their overt cooperation, midwives are first and foremost deeply loyal to the women they serve. For this reason midwives have constantly been denied the right to form a guild, to organize themselves into an autonomous corporation. No official bonding is permitted among these masterless women; they already seem conspiratorial enough. Doctors and surgeons are relieved that midwives have no recognized channels for grouping together, asserting themselves, seeking legal redress, or voicing grievances.

Independently, however, these women play powerful roles in the greatest drama of life.

5—

A Birth:

Paris, January 1744

This baby is finally coming, ready now to make its dive into the world—with the help of an accoucheuse , of course.[1] For months Le Boursier, a robust woman of twenty-nine, has been looking in on the mother-to-be, providing oils and liniments to keep the growing breasts and belly elastic: white pomades of melted pork fat purified with rose water, others of calves' foot marrow, the caul of a baby goat, goose grease, linseed oil, almond paste, and marsh mallow. She counseled the use of supporting bandages recently as the stomach really began to sag, and suggested the woman sleep on one side so that the opening of her womb, a bit off kilter, would be pulled by gravity into alignment with the vagina.[2] To keep the bowels moving and avoid constipation, which only exacerbates the inevitable hemorrhoids, enemas have been administered regularly—mixtures of bran, oil, butter, and river water.[3] There was a false alarm in the seventh month when the baby, who had been sitting up, suddenly turned a somersault and reinstalled itself upside down. The woman had feared she was in labor, but the midwife, upon examination, knew better.[4]

Bloodlettings have been performed at least once a month throughout the pregnancy—whenever the woman felt short of breath or nauseous, got dizzy, bled from the nose, or presented varicose veins in the legs—to relieve tension in the organs and prevent premature delivery. Once before this woman had been pregnant, but lost the baby because another midwife had not known to bleed her.[5] At least she has not needed purgings of manna, rhubarb, cassia, and senna, because she has been spared the bad breath, livid skin tone, and bilious vomiting that many others suffer and for which such remedies would be indicated.[6] The midwife has cautioned her to avoid excessive passions and to coif herself with care, combing and styling to get rid of vermin and to keep herself decent and presentable despite her fatigue. She may powder her hair—nothing with a strong fragrance, though—and put on a bonnet so she won't need to fuss with it for twelve to fifteen days and so her head will stay warm.[7] Walking is recommended, to keep the sinews strong and resilient. Cleanliness is not mentioned—only women of pleasure wash and bathe frequently—but clothing is to be loose and comfortable, the

bed firm and dry, the diet moderate. No ragouts, sauces, fatty meats, or aliments de fantaisie .[8]

Now a few female friends, neighbors, and relatives have gathered, responding to the baby's quickening. They will help the midwife, as their familiar faces afford comfort; but if anyone's presence upsets or inhibits the mother, that person is quickly removed. The room is fresh and airy; it must not be allowed to get too hot.[9] The patient (la malade ), as the birthing mother is called, has been put to bed and will stay there through the delivery. She has only light covers over her. Incontinent these last few days from her great womb pressing on her bladder, she is now, instead, retaining her urine, because the baby has moved down, squeezing the neck of the bladder almost shut. By introducing a hollow tube, an algalie , up into the urinary passage, the midwife quickly relieves that discomfort and watches the bright yellow fluid gush out.[10] This obstruction cleared, the labor pains come more often now. The midwife's greased fingers skirt around the neck of the womb, normally the size of a fish snout or the muzzle of a small dog, and feel the opening growing larger. When it has dilated to the size of a large coin, an ecu de six livres , the serious ministrations begin. On a strong contraction the midwife breaks the waters, piercing the mother's taut membranes with a large grain of salt; and to ease the breathing, lessen engorgement, and soften the cervix so it will stretch and open more easily, she bleeds her from the arm.[11]

The mother strains now, rolling and rocking. A more comfortable position will work better, head and chest raised, legs spread, heels planted against her buttocks, knees held apart by a helper. She is a slight woman with a narrow pelvis, and it is a big baby, a boy from the way the frame feels, although the midwife cannot be sure. Hours have gone by; the cervix is quite open, and still the head has not crowned. A malpresentation certainly, but just how bad is it? If any part other than the head presents, the delivery will have to be breech. The midwife checks the extent of dilation, speaking in comforting, affectionate terms to the mother, encouraging her, assuring her that she is not in danger, telling her honestly that things will still take a long time, for unrealistic expectations and impatience could make her tense, worsening the pain.[12] There is no point in trying to rush nature; the birth will progress in due course.

All along, under the bed linens, the midwife is continuing her tactile exam with fingers and full hand. Mucous, blood, and the waters provide natural lubrication. She hardly needs to look, and it would only offend the mother's modesty. A less experienced midwife could make a terrible mistake right about now. Desperate to hurry things along, she might put a finger into the mother's rectum to push the baby down, but this can ulcerate the anus and destroy the separation between the bowel opening and the vagina, rendering the woman "very disgusting."[13] Too much vaginal meddling is bad too: it can inflame the bladder. The best thing is to wait patiently, alert to all cues. The mother pushes a little, blows into her hand, and the midwife gently rubs her stomach, speaking in soothing tones.

Changes now. The baby is coming faster. She feels a bulge, not hard enough to be the head, too big and round for an elbow or a knee or a foot. It is almost surely the baby's bottom. She feels the crack between the soft buttocks, and up higher the fold of his thigh. Refraining from probing any further, for fear of releasing the black, tarlike meconium from the baby's rectum, she must move quickly before he engages too low.[14] Inserting a well-greased hand and following the rear, thigh, knee, and lower leg, she takes a foot down into the birth passage, then goes back in for the other one so the knee doesn't get caught. To do this between the womb's powerful contractions the midwife's arms must be very strong. Slowly, with the mother's help as she pants and pushes, she pulls the two feet together, evenly, steadily, out through the vagina. She wraps them in a soft, dry cloth so they won't slip out of her hands. Once the knees are out she must flip the baby, because he is coming with his chin facing up toward his mother's navel, and in this position his jaw will catch and get stuck on the pubic bone. She continues pulling gently on the little legs as she turns the baby around so his nose is now facing down toward his mother's backside. Straightening and bringing down the arms doesn't deliver the head as it usually does, so Le Boursier asks one of the women to hold up the half-born child, thus freeing both her hands. Deep inside the mother now, she seizes the baby's lower jaw and slides the index finger of her left hand into his mouth, while her right hand pushes down on the back of the baby's head to release it. With both hands she tucks

and pulls the head out and up toward her while another assistant, at the same moment, coaxes out the big shoulders. None too soon, for the ordeal has left the mother completely exhausted.[15]

The newborn baby boy's cord is tied in two places and cut between the ligatures with a blunt scissors. He seems rather weak; there are faint sounds but no robust wailing. The women wrap cloths soaked in strong wine or eau-de-vie around the cord stump and over his head, chest, and stomach. Some liquor in his mouth, some crushed onions near his nostrils, bring him around dramatically. He lies briefly against his mother's private parts, nesting and squirming. After a few minutes, since he is out of danger, the women take him and wash him in lukewarm wine and fresh butter to remove the muck. Soft worn cloths soaked in oil envelop the cut cord, and a bandage around his middle holds this compress in place to prevent umbilical hernia when he cries, which he is doing a lot now. They bundle him up in toasty linen.[16]

The midwife turns back to the mother, who is relieved and spent, but her work is not finished yet. She must push another time or two to help the placenta out. When some gentle coaxing on the cord still doesn't deliver the afterbirth, Le Boursier goes in with her whole hand to explore, but it is stubbornly adhering. She injects into the womb some mallow, pellitory, linseed, and fresh butter, gives the mother a drink of lukewarm cinnamon water, syrup of artemisia and almond oil, tries an infusion of couch grass with syrup of sour lime, adds orange juice to the bouillon. None of this is working and too much time has gone by, so the method of last resort comes into play. The woman stands up in a tall vat of hot water. She pushes while the midwife rubs vigorously downward on her thighs until finally, all intact, the "secondine" is expelled. Once the attendant women have examined it and determined that it is complete, the mother lies down again, covered and protected from cold. Finally she can rest.[17]

Attention turns now once again to the baby, who has been slumbering on his side. He gets another wash in warm water and fresh wine, and then he is swaddled again, this time with his legs free to kick. This is far better, the midwife boasts, than the tight wrapping and binding that prevail in some other countries; few French babies are bandy-legged as a result.[18] Once he seems to be comfortable, the mother becomes the focus again. She is helped with her toilette and

the bed is prepared so that she can sleep. Luckily there are no signs of unusual lethargy or convulsions, or a doctor would need to be called in.[19]

Le Boursier will watch the mother closely over the next days, to make sure all is well. As soon as she is strong enough, a trip will be made to church for the baby's baptism. The midwife will make all the necessary arrangements with the curé , or parish priest. She, rather than someone else, must present the baby because her word is trusted to certify its sex. If a domestic were to present the baby, he would need to be undressed and examined for visual verification, and this is considered indecent in church.[20] The midwife has also lined up a wet nurse (nourrice ). For the first twenty-four hours of his life, while he is getting rid of phlegm, the baby drinks warm wine with sugar, syrup of chicory with rhubarb, or boiled and strained honey water to get his digestion going. At first it had seemed a surgeon might need to be called to open a membrane across the baby's anus, but now the bowels are moving freely.[21] Tomorrow he will begin to suckle at the breast of his nourrice . May she not roll over and crush him in her sleep![22]

Because this mother is of a "delicate complexion" and will not nurse her own baby, a regimen is prescribed to prevent milk fever. Breast milk is believed to be nothing other than menstrual flow that rises in the body, fades in color, and is transformed. The garde , hired to stay with the mother, will bring her bouillon every three hours; it mustn't be made from veal, which causes diarrhea. If she is terribly hungry, she may have a soup of soaked white bread cut thin and small, easy to digest. She should also drink infusions of couch grass, or lukewarm water with a little wine, or syrup of maidenhair fern. In five or six days she will be allowed some poultry in the morning, but not in the evening until she is walking and exercising. The garde must check the mother's chauffoir , a kind of diaper, for blood clots and a flow that is bright red and normal. If it stops or becomes pale, it means too much milk is still going up to the breast. Then a bouillon of chervil will be called for, with arcanum duplicatum or Glauber's salt dissolved in it, and the breasts, kept covered and warm, will need to be treated with an unguent of marsh marigold or olive oil with tow of flax, or honey, to prevent engorgement.[23]

The new mother is suffering because her parts are somewhat torn. Embarrassed, she reluctantly confesses this to the midwife,

who tells her she must help along the healing by bathing herself in a soothing lotion of milk and herbs. A mixture of water and vinegar and some hot wine alleviate the itching. Her diarrhea can be calmed with an enema of milk, egg yolk, and sugar, changing after a few days to a potion of equisetum and pomegranate peel with an egg yolk twice a day.[24] The diet of good bouillon must continue, and she can eat some jelly. Because she is still bleeding, cloths soaked in oxycrate, a mix of water and vinegar, are wrapped around her thighs and placed under her back. Some powdered Spanish wax, about a hazelnut's worth, dissolved in six spoonfuls of water, should be swallowed, followed by a second dose. A brew of wild chicory, orange blossoms, syrup of diacode , and capillaire will help too. She must sniff cloth soaked in Queen-of-Hungary water, which will strengthen her heart, as will drinks made from comfrey root and rice, and sap of purslane. And she continues to be bled from her arm.[25]

Soon the midwife will give some vaginal injections and fit the mother with a pessary made of cork and layers of wax to hold her womb where it belongs. Its ligaments have been loosened by the strains of childbirth, and it might prolapse completely without support. If the pessary gets dislodged, it needs to be dipped in wax again, and again, until the added hardened layers enlarge it sufficiently to stay in place. A hole in the center allows the woman to conceive.[26]

And so the whole cycle will begin anew.

6—

The Petition:

Paris, 17 May 1745

For many, it is a day like any other in the tumultuous capital, with its unique mix of luxury and filth, of magnificence and obscenity, its changing cacophony of sounds. Heavy spring showers have for weeks now sent rainwater gushing from the roofs of the many-storied buildings, making rivers of mud in the narrow, packed streets below, where people jostle, shove, and splash one another. Enterprising Auvergnats run about with planks to improvise bridges whenever they spot well-dressed pedestrians who might be willing to pay to keep their feet dry. Huge shop signs made of wood or heavy iron depicting the various trades—cobblers, glovemakers, perfumers, butchers—protrude high above the storefronts, creaking omi-

nously in the wind. Midwives' signs usually show a cradle or a child leading a pregnant woman and carrying a candle. Scents of wet stone, ashes, wax, leather, soap, bread, sage, wine, grease, damp straw, fish, rotting apples, feces, and blood from the slaughterhouse near the Châtelet permeate the air. Shrill voices resound—merchants hawking their wares, town criers bellowing out royal edicts—filled in by the background shouts of bargemen floating west on the brown-gold Seine, the din of the blacksmiths' hammers, the clatter of carriage wheels and horses' hooves, and the tintinnabulating bells of a hundred churches. Sturdy women plant themselves on the corners, rain or shine, carrying on their backs large tin canisters of café au lait, which they serve, with little or no sugar, in earthenware cups for two sous.

A habitual sequence of events unfolds in Paris. At 7 A.M. gardeners with empty baskets on decrepit horses return to their little plots having sold their goods wholesale to the market during the dawn hours. At nine wigmakers scurry to coif and powder their clients, while young horsemen followed by their lackeys go for a practice gallop on the boulevards and make fools of themselves falling off. At ten there is a parade of black-robed justices going to the courts with plaintiffs running after them. Noon brings the money men to the Bourse, and solicitors of all stripes to the quartier St. Honoré, where financiers and men of rank have their dwellings. By 2 P.M. the carriages are in great demand as everyone scrambles to find a ride; passengers often come to blows, and police have to intervene. Three ushers in a peaceful spell; few are in the streets, for everyone is eating. Quarter past five, on the other hand, is truly infernal. There are crowds everywhere—on the way to the theater or to the promenades—and the cafés are overflowing. By seven it is calm again, although as night falls criminals come out of hiding and honest citizens must watch their step more carefully. Now carpenters and stonecutters head back to the outskirts of the city, whitening the streets with sawdust and plaster from their feet. As these laborers turn in after a long, hard workday, the marquises and countesses are just rousing themselves to begin their toilette! Nine is noisy. Theaters let out, many make their way to dinner engagements, prostitutes solicit potential clients. By eleven supper is finished, cafés disgorge. At one in the morning six thousand peasants arrive at Les Halles on their exhausted mounts, bringing vegetables, fruits, and flowers from the surrounding countryside. After

these produce deliverers come the fishmongers, then the wholesale egg merchants with their precariously balanced pyramids of baskets. A similar scene takes place on the quai de la Mégisserie, but here instead of salmon and herring there are straw cages full of hares and pigeons. The rest of the city sleeps through most of this. At 4 A.M. only brigands and poets are awake. At six the bread gets delivered from the boulangeries of Gonesse; laborers rise from their straw pallets, gather their tools, and go to their workshops, stopping on the way for café au lait, their breakfast of choice. Libertines stumble out pale and rumpled from the whorehouses, gamblers emerge into the brutal light of day, many hitting themselves in the head and stomach, looking heavenward in desperation. And then everything starts over again.[1]

Babies, however, are born any hour of the day and night, so Le Boursier is on call around the clock. There are no set rhythms or patterns to her schedule, although its very unpredictability in a sense becomes routine.

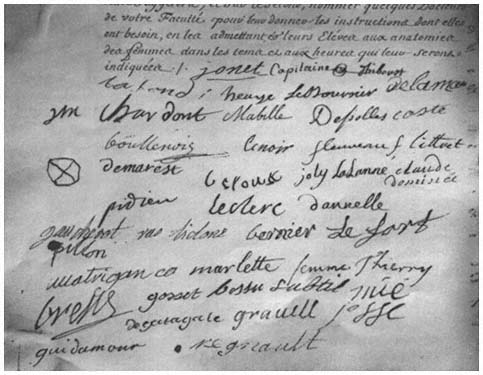

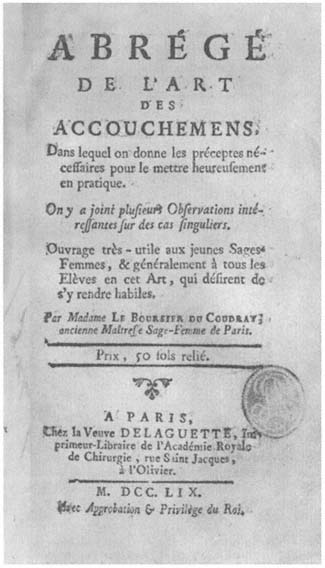

For her, though, today is special. She is one of forty midwives who have just signed a petition urging the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Paris to provide them with instruction. Her name appears near top center of the signatures (fig. 3), immediately after those of the four official sworn midwives of the city, jurées whose job—bought and usually passed down within a family—is to oversee the craft, make known infringements, collect fines, and expel offenders. If Le Boursier has not spearheaded this rally among sister practitioners, she was at least one of the first to approve it.[2] A few of her cosigners demonstrate a fluid, easy hand; many more make quirky scrawls and seem to find writing awkward, as though they rarely have occasion or need to join letters together, and one who cannot write at all marks the document with an X. Le Boursier's manner of signing, though not flamboyant, seems sure and practiced among the clumsy ones. She has been a midwife in the capital for many years and is no stranger to writing her name.[3]

Organizing for this petition was not easy. Midwives are deliberately kept as subordinate members of the guild of surgeons, "to whose policing they must submit," and have historically been deprived of a separate, recognized voice. There is "absolutely no community among them," gloats the surgeon Louis in the Encyclopédie with obvious relief, reassuring himself and his readers, as if an independent consorority of these women would be a nightmare.[4]

Figure 3.

A rare look at the handwriting of forty midwives on a protest

petition. One cannot sign, some obviously sign rarely and with difficulty,

some have a fluid, confident signature. Le Boursier (as Mme du Coudray

was known in Paris) puts her name near the top.

Lacking a corporation of their own, they have no meeting house, no built-in avenues for sociability, no established network of communication. They are excluded from academies, ignored by the press, never eulogized after death as are male practitioners. Even annuals like the Almanach royal in these years leave them out of the lists of health officials. So solidarity and camaraderie among them are not fostered, do not come naturally.

There are, however, some old rules that encourage a kind of interdependency. Midwives cannot be approved for their licenses until authorities learn about their lifestyles, so they are sometimes asked questions about their colleagues.[5] Do they live wholesome lives, eschew profanity, practice discretion? As far back as 1580 statutes and regulations forbade midwives to use any dissolute words

or gestures or to speak ill of each other, unless it was to expose anyone among them who conspired to help women "kill their fruit."[6] Back then, in the late sixteenth century, Paris had only sixty midwives, and it may have been easier for them to know one another, whether personally or by reputation. But ever since then there has been enormous migration to the capital, and the expanding population has naturally swelled the demand for midwives. These days there are about two hundred of them scattered around and out into the burgeoning faubourgs .[7] Presumably they see each other monthly at the first-Monday services at the church of St. Côme, although it is not clear how rigorously they attend.

Yet something has occurred recently to pull forty of the most enterprising among them together. Disenfranchised though they may be, they have a shared grievance now, and they have mustered the stoutness of heart to initiate a protest. Since 1733 midwives have been admitted to classes at the school of surgery on the rue des Cordeliers. César Verdier was the demonstrator for anatomy, Sauveur-François Morand for dissections and surgical operations.[8] Recently, however, these lessons were closed to them, and the women are now turning to medical doctors, the surgeons' age-old rivals, for help. Doctors, with their Latin, their robes and bonnets, and their university schooling, have always fancied themselves greatly superior to surgeons, whose roots lie in the more practical artisanal tradition, so the women request their intervention. Exactly how many midwives have actually been attending these lectures is not known, but the forty who assemble today to complain about their recent exclusion obviously feel debarred from what had become, at least for them, an accustomed right.

Not only are the midwives intellectually deprived; they fear that their very profession is in jeopardy. The petitioners complain that for the past two years the normal testing and reception of aspiring midwives by Paris surgeons has also been suspended. The "dangerous consequences of such a cessation" are now rampant. Many women, finding the credentialing examination at St. Côme unavailable, have simply been setting up shop without it. The city's sworn, official midwives have forced such illegal practitioners to "take down their shingle," but these are put right back up again, the defiant matrons claiming that they have studied and therefore deserve to profit from their vocation, and that it is not their fault if surgeons refuse to test them. These women, though they have broken the rules, at least

boast some training. But others—their names are provided in the petition—upon hearing there are no more formal receptions, have begun to practice without any background experience whatsoever. Expectant mothers seeking help from these unscrupulous characters court, according to the signers, the gravest peril.

The petitioners go on to demand instruction in reproductive anatomy, which will replace the classes now suspended by the surgeons. Understanding the "parts used in generation," far from being "vain curiosity," allows them to serve their clients better than the purely empirical training they have received as apprentices. In particular, they feel unsure about when to call for help; some are too secure, nearly foolhardy, others overanxious and lacking in confidence. The group now formally asks that doctors provide regular demonstrations for them and admit them and their students to all dissections of female corpses.

In response to this pressure the members of the medical faculty, unaware that the situation had gotten so out of control, move very quickly. They promise to prepare and distribute a yearly list of officially approved midwives, which should put an end to the anarchy and help regulate the profession. They assign one professor, Exapère Bertin, to teach bone structure, and another, Jean Astruc, to teach delivery, both for free and in an accessible form—in French, not Latin—in their school amphitheater on rue de la Bûcherie. The classes are to start immediately. They even try to get some cadavers from the hospital administrators, despite the fact that between 1 May and 1 September, because of putrefaction in hot weather, autopsies are not allowed. In an effort to persuade, the doctors boast about their latest facility, a beautiful rotunda with a dome built just last year, magnificent and modern: "Our amphitheater is new and cool. The demonstrator will prepare the [cadaver] parts with spirits of wine and aromatic essences and take all precautions so that his work will cause no foul smells . . . in neighboring houses." Despite this plea, a response to the medical dean from the chief of police denies the request for bodies because of the season; the lecturers continue anyway, doing the best they can using skeletons. Twenty-three lessons are given, to which "the midwives most in demand [les plus employées ]" and their apprentices flock in large numbers.[9]

Why are the doctors so eager to help out? And why since 1743 have surgeons turned their backs on their teaching and licensing duties? Perhaps because on 23 April of that year the king gave a

great boost to the status and prestige of surgeons, separating them squarely from any demeaning past association with barbers and wig-makers, putting them now on the same lofty footing with doctors, their historic enemies. The year 1743 was the beginning of the personal reign of Louis XV, who was very much under the influence of his first surgeon, La Peyronie.[10] The chronicler Barbier predicted then that, because the science of doctors was merely conjectural, surgeons with their combined practical experience and book learning would soon be the only experts needed.[11] Do the newly favored surgeons, imbued suddenly with a fresh sense of importance, simply believe the approval of midwives to be beneath their dignity? Or do they wish to squeeze out female practitioners completely, thus eliminating any competitive and menacing alternative to the male surgeon accoucheurs already fashionable in high social circles?

The midwives suspect the latter. They feel cheated because the "masters of their community" who owe them instruction are withholding it. They soon complain again to the medical faculty, that "the more carefully they watch the conduct of master surgeons toward them the more they are persuaded that they wish to destroy them in the [eyes of the] public even though they are part of the same community." They thank the doctors for responding to their request for instruction with such "clarity and precision." Surgeons have apparently complained that Paris has too many midwives already. The petitioners protest vociferously. There are fewer than two hundred they say, some of whom are far too elderly to practice. New ones take a long time to train, as private apprenticeship lasts three years. And now the Hôtel Dieu, which forms midwives much more quickly in several months of intense clinical training, is distributing most of its graduates outside of the capital into the provinces.[12] As a result, only six or seven new Parisian midwives present themselves each year, while at least that many retire. "Such a small number in a city as extended and as populated as the city of Paris shows that, far from being overabundant, [the supply] is not even sufficient." The timely reception of new, legitimate midwives must be reinstituted. Surgeons, the petitioners now claim unequivocally, "are trying to deprive midwives, against order and the public good, of the fruits of a profession." The group urges doctors, magistrates, and the lieutenant of police to force surgeons to recognize their error and resume their duties as instructors and examiners.

The doctors seem ready to do anything to embarrass their professional rivals, including the forging of this temporary alliance with the midwives. And the women do not hesitate to exploit the traditional animosity between the two groups of male practitioners, whose polemics have been at fever pitch for the last two years, if it means achieving their aim of better training and regulation. The surgeons, however, despite their scorn for their female underlings, seem unready to relinquish control of them, and vow to put a stop to the doctors' encroachment. The midwives must not fancy that they can go over to the other camp permanently. "You will never escape from our corps , whatever entreaties you make. Alert your companions, because no matter what you try you will only be the dupes."[13] And indeed, the doctors' lessons soon cease.

Being caught in this crossfire, pawns in this game, is humiliating for the midwives. Surgeons are busy making a display of their new professional and academic status; doctors are busy doing anything and everything to protect their traditional prestige. Both groups are far more concerned with their personal interests and privileges than with helping the midwives. They give hollow, false promises at best. The petitioners seem overworked, insecure, forsaken. That they band together and demand more thorough education shows they possess at least some sense of a shared work identity. But what is driving them is not chiefly female pride. A large part of the grievance here is against female quacks practicing blind, murderous routines. "It is to the mercy or rather the rashness of such women that the life of other women and children is surrendered." These petitioners do not experience—or at least do not express—the indignities they suffer at the hands of surgeons as affronts to their sex, but rather as professional usurpations. Job-related alliances like this petition doubtless offer some consolation, but there is little sense of sisterhood under such circumstances. The issues here are not framed in terms of women defending themselves against men.[14]

Le Boursier signs the petition beside one Heuzé, with whom she will exchange an apprentice several years from now. Perhaps they are friends who afford each other mutual support. For now, though, they are only two of many midwives whose collective work is not properly appreciated, not receiving adequate recognition. They are lost in the crowd, their reputation suffering because charlatans masquerade as colleagues. To observers commenting on the group, the

superior practitioners are indistinguishable from the others. One doctor, musing on the fact that midwives were once highly esteemed in Greece and Rome, laments: "To see the low opinion of midwives in Paris, one is tempted to say 'past honors are only a dream.' But we must focus on individuals who practice this profession and not on the profession itself. . . . There are many who should be excepted, even singled out with high praise; but we have often seen crime obscure the virtue that walks beside it."[15] Is the future of Paris midwifery imperiled, even for this enterprising group of petitioners who crave learning in addition to technique? Could Le Boursier already be thinking she must break away if she is ever to shine?

Whatever her thoughts may be at this point in her career, she is making the best of it in Paris. She and Heuzé may even have been designated or have assumed the role of unofficial leaders of Parisian midwives, for their signatures are the first after the pro forma list of jurées , women who have inherited the title but are not necessarily good at rallying the group. That Le Boursier denounces as abusive the threat posed by surgeons and quacks to her livelihood, that she organizes or joins others who regard it also in that light, is perhaps an early indication of her strong sense of self. It is impossible, naturally, to do your best work when such obstacles are thrown in your path. There are things about the Paris scene that are irksome, even mortifying. If the surgeons think she will be cowed by their snub, waiting submissively for the affair to blow over, her activism for the petition shows otherwise. What satisfaction there would be in turning the tables on them some day!

And there is all this new talk, especially at the Hôtel Dieu, about well-trained midwives being so sorely needed in the provinces right now. Might this be when the idea of leaving and setting out on her own first takes root in Le Boursier's mind? Whether it is or not, for a while still she will stay here in Paris, biding her time.

7—

Apprentices and Associates:

Paris, 22 January 1751

Today Le Boursier takes on a new apprentice. It would have made no sense to have one these last six years because all that time the surgeons stayed on strike, refusing to resume their duties.[1] It finally

took royal intervention to halt the conflict, and only lately have things begun to pick up again, so there is quite a backlog. The petitioners had estimated that six or seven apprentices usually finish each year. Now, to make up for the lost time, twenty-five women sign up to begin three years of training with mistress midwives throughout the city. The ranks must be replenished.

Angélique Marguerite Le Boursier seems still to be unmarried, for the notary who draws up the arrangement, scrupulously thorough about such details, mentions only the marital status of her apprentice. Madeleine Françoise Templier, widow of the baker Fourcy, has for the last four months been apprenticed to Marie Anne Heuzé, but quite recently she moved to rue St. Croix de la Bretonnerie, where Le Boursier lives. She no doubt finds it more convenient to have a near neighbor for a teacher. In any case, she now makes a new contract reflecting the change. Three hundred livres will be paid to Le Boursier for three years of training, during which the midwife will "show and teach [her apprentice] all that her profession involves." The student will live in her own home and dress and eat at her own expense, but she will come to Le Boursier's residence, or accompany her on rounds elsewhere, whenever needed.[2]

This is a very advantageous contract for Le Boursier. Such a student is an important source of income, and indeed, Heuzé loses no time finding another for herself, just six days later, negotiating similar terms.[3] These two women drive a hard bargain. Most midwives charge their apprentices considerably less, give them considerably more, and spell out precisely just what the conditions will be. Le Boursier's contract, however, is sketched in abbreviated terms, as if working with a midwife of such distinction and reputation is enough in itself.

Usually, contracts made by Le Boursier's colleagues are elaborate, and mutual obligations intense. One midwife pledges "to show her whole art . . . without hiding or disguising anything, and to alert and call" her student to come with her everywhere. The aspirant, for her part, will "learn with all possible attention the art of delivery, agree to all that can contribute to her instruction, do for mothers and for children all that a midwife should, and generally listen to and practice all" that she is shown, "day or night."[4] Most midwives promise to "feed, sleep, lodge, warm, and light" their students, even wash their laundry—towels, sheets and clothes—in addition to teaching them, thus taking on a maternal role. Most

students stipulate that they will "enhance the profits" and "prevent the damage" of their teacher, that is, warn and protect her against injury to her reputation. They also swear "never to leave or work elsewhere during the three years" and, in case of flight, to submit to finishing out their obligations after being hunted down by the searchers dispatched to find them.[5] Some midwives commit themselves to teach about medicines and remedies, bandages, fomentations and fumigations, as well as about childbirth itself. Some students specify that they will follow the midwife faithfully as long as she is trustworthy, "obey her in all she asks that is honest," "reasonable," and "licit."[6] The reciprocal agreement is for the exchange of ethical attitudes as well as skills. Whereas most preprinted apprenticeship contracts, kept handy by the notaries with blanks to be filled in, talk of learning a "trade" (métier ), midwife contracts are worded differently. They call this line of work an "art."[7]

Arrangements vary considerably. One woman from Meudon puts her sister into apprenticeship for only three months, because she will practice in the countryside where regulations are quite lax, in some regions nonexistent.[8] Another provincial, from Champagne, the wife of a master founder, is determined to take the full three-year course. She pays 250 livres for this apprenticeship.[9] It is curious that she is willing to spend long years away from her hometown, but perhaps she has been urged to do so, even subsidized, by the authorities of her region, who are zealous about securing thoroughly trained practitioners.[10] Most provincials study for a much shorter time, although such truncated training limits their marketability, obliging them to keep their practice outside the capital forever.[11]

A few contracts involve family members. Two sisters-in-law have an arrangement in which one instructs the other "without a single sou being exchanged."[12] But even within families some considerable sums are paid for instruction, with all manner of guarantees and collateral stipulated to make the obligation binding. The wording can be dramatic. The husband of one apprentice pledges "solidly" to pay the necessary fees, or lose all his earthly goods.[13]

A midwife might agree to teach a next-door neighbor for free, simply taking her around to watch and help during a three-year period. In one such case on the rue des Fossés de Monsieur le Prince, the apprentice is single, the midwife married to a master perfumer.

Perhaps his income is sufficient for his wife not to be preoccupied by gain.[14] Others may simply enjoy the company and assistance. Usually neighbors do exchange money, 100 livres, 200 livres.[15] Le Boursier's 300 livres for such an arrangement, however, where no hospitality is offered, no responsibility assumed for the apprentice short of the instruction itself, is very high. She must already consider her teaching of sufficient quality and value to command a superior price without providing any fringe benefits for her pupil. And she is apparently uninterested in having a boarder, companion, or surrogate daughter as do so many of her colleagues. Life can sometimes get rough for apprentices; they can be a burden. One midwife will take an apprentice from the provinces who, when seduced and abandoned by an old doctor promising to help her advance in her career, exposes him and creates a public scandal. Though the apprentice wins a good financial settlement, her reputation is ruined and the whole affair is most unpleasant.[16] Le Boursier avoids these sorts of entanglements.

Apprentices frequently present themselves alone, of their own volition; others are brought before the notary by husbands, older sisters, or parents who wish to prepare them for a secure profession. One seventeen-year-old orphan is presented by the guardians who have cared for her since age four.[17] Midwifery continues to be regarded as a valuable, worthy female trade, despite the dire scenario foreseen six years ago by the petitioners, in which they would be irreparably sabotaged by the surgeons. Dancing masters, financial administrators, clerks, cobblers, prisonkeepers, printers, pastry chefs, caterers, locksmiths, and journeymen all willingly pay large sums for women in their family to acquire expertise in the art of delivery.[18]

One midwife, dame Bresse, requires an all-around helper, a woman to serve as domestic and personal secretary. So her twenty-year-old apprentice pays her no money for the three years of training but agrees in exchange to see to the "needs" and "personal affairs" of her teacher, to be generally "at her service."[19] Quite a number of midwives have responsibilities managing the household accounts and so seek clerical help.[20] One brings to her marriage a dowry of several thousand livres.[21] Another has been part owner of some property in Fontenay.[22] Another brings only 500 livres but marries a man with nearly 10,000 and many investments.[23] One midwife, widowed after twenty-eight years of marriage and the mother of seven

children, decides to apprise her eldest son, a soldier, of their estate. The current value of everything after the ebb and flow of life for nearly three decades—itemized down to the gold buttons on some sleeves—is now 4,213 livres, 2 sous, 3 deniers. When all is said and done, each of the seven children will get a rather paltry inheritance, but it must be accurately calculated nonetheless.[24] Severe economic reversals can occur quite suddenly with widowhood. One midwife whose surgeon-husband dies abruptly needs to sell all her belongings to pay three months' back rent for the apartment she sublets. The inventory of this sale shows she occupies several rooms cluttered, indeed overflowing, with possessions—numerous feather beds, straw mattresses, cots, serge curtains, wall hangings, and armoires.[25] Almost surely the many furnishings and tapestries have been used in the private partitions described by Mercier. What will she do, even with her back rent paid, in this suddenly empty apartment, once the scene of much activity, the temporary refuge of numerous pregnant clients over the years, now stripped and bare?

Le Boursier's colleagues are scattered all over the city, although some very populous quarters seem to have more midwives than others. According to records from the 1770s (no lists for earlier periods have been found), several of the Right Bank neighborhoods, teeming with inhabitants, have as many as twenty-three, sometimes even a few clustered on the same street. Le Boursier's quarter, St. Avoie, near the graceful recreational boulevards and full of grand homes and gardens, has only two.[26] Has she expressly chosen to be a big fish in a smaller pool? Does this put her in greater demand and ensure her a healthy, wealthy practice and singular reputation even before she enters public service? Or is it that her presence discourages others with lesser reputations from establishing themselves there? The Marais, where she lives, once an aristocratic bastion, still has many nobles, magistrates, and others of distinction. Rue St. Croix de la Bretonnerie, her street, is itself the home of several provincial intendants, royal ministers, and bankers.[27] It is quite likely that Le Boursier has gotten to know during these years some prominent and powerful neighbors, whose financial support and political assistance will soon become important to her.

She also frequents and befriends colleagues in the medical field. She has been acquainted with the surgeons Morand and Verdier since their lectures at the anatomy courses for midwives at St. Côme.

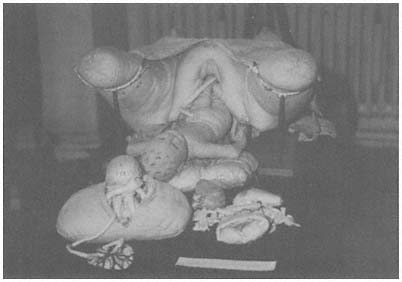

Old-timers who have been practicing since 1724, they were probably on her jury when she completed her apprenticeship and took her qualifying examination. They seem not to hold a grudge from the petition days of accusation and recrimination, and will facilitate things for Le Boursier later on. Morand will do this in his capacity as royal censor. He seems to take particular interest in sponsoring talented women, and has given special encouragement also to a Mademoiselle Bihéron, who fashions precise anatomical models out of a secret lifelike wax substance. A former midwife who now devotes herself entirely to this "artificial anatomy," she holds weekly visiting hours in her home cabinet , where these pieces are on exhibit, so realistic, it is said, that only the smell is missing. She is presently preparing a collection of models commissioned by Catherine of Russia to be sent to hospitals and displayed in the museums of St. Petersburg, and Morand is lending her his patronage. Le Boursier, typically, never mentions Bihéron, but these wax models of pregnant women might well have been the inspiration for her own later mannequin made of cloth. Verdier, a peerless lecturer and close friend of Morand, will later pen some obstetrical "observations" to be published alongside Le Boursier's textbook.[28] She is also acquainted with the Sües, a veritable dynasty of influential medical men, three of whom, a father, a son, and a first cousin, will come to the midwife's aid in a variety of ways.

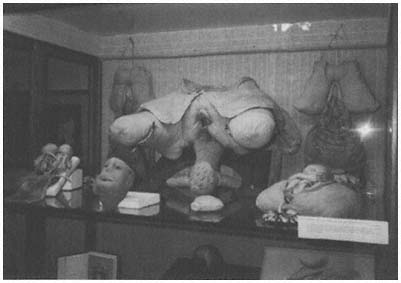

But Le Boursier's most important contact from the Paris years is the maverick lithotomist Jean Baseilhac, known internationally by his nickname Frère Côme, for this celebrated surgeon is a monk. He is a fascinating character in his own right, as his swashbuckling portrait seems to bear out (fig. 4); a native of Tarbes in the south of France, he has recently discovered and perfected new techniques for cutting out stones, and for curing cataracts. Special instruments of his own devising are made for him by a favorite cutler on the rue Galande, and he tries them out on patients at the Hôpital de la Charité. He also experiments on corpses. Though a great humanitarian, so intense is he in his research, so enthusiastic about his findings, that he is said to have lamented the recovery of a person whose cadaver he was particularly curious to dissect! An expansive and generous man, he is devoted to healing the poor, for whom he has set up a number of free medical clinics, but constantly sought out by the rich and famous, especially many in the king's immediate

Figure 4.

Frère Côme, the famous medical monk, assisted Mme du

Coudray and managed her mission in various ways behind the scenes.

Photograph courtesy of the Académie Nationale de Médecine, Paris.

entourage. In the mid-1740s his virtuosity came to the attention of the king's first surgeon, La Peyronie, and ever since he has been a darling at Versailles. Superior orders forced the Paris surgical community to accept him into their fold, but his unorthodox methods and the favoritism shown him at court have made most of the members of the Academy of Surgery too resentful to welcome him.

He has a deep, genuine commitment to the destitute, an enormous talent, a colorful personality, and an entirely unique and very powerful position in the medical landscape, won by skill, of course, but also furthered by people in high places. Le Boursier will develop along these same lines, and perhaps he foresees this potential in the gifted, ambitious midwife. He probably teaches her how to exploit good connections, how to use letter writing to her own ends, how to generate a network of supporters and gather their written testimonials, how to create and enjoy special idiosyncratic freedoms. He has perfected and used these methods for years, and she is much influenced by his example. He will later claim to have groomed her for her great task.[29]

In any case, Frère Côme is to become her principal fan and impresario. His unflagging support for her, which will last until his death in 1781, is a mixed blessing. That she has a strong, influential man working behind the scenes to sustain her during three decades is not bad. That he is a flamboyant personality who gets distracted by his own exciting projects and makes as many enemies as friends is not good. The famous Rouen surgeon Le Cat, for example, hates Frère Côme and calls him Frère Coupe-Chou because he lacks the usual university credentials and behaves in such an earthy manner. Another medical colleague, the eye specialist Daviel, who peddles a rival cataract procedure, refers to his own method as Davielique and to Frère Côme's as Comique in an unsuccessful attempt to reduce the monk to a laughing stock. There are also far more insidious attacks on his reputation, and even physical assaults on some of his disciples. He survives all this, his energy undiminished, and remains steadfastly loyal to the midwife, raving about her wherever he goes. And he travels widely. He does enough for Le Boursier's reputation through his solicitations that doctors and surgeons both at court and far beyond know well who she is and marvel at her abilities.[30]

Frère Côme realizes as well as anyone the desperate need for good midwives in the provinces. An enquête back in 1729 revealed the woeful state of rural delivery practices, one panicky priest near Laon estimating that more than 200,000 country babies were dying each year.[31] The monarchy responded, and since 1735 the Hôtel Dieu has been training provincial midwives almost exclusively.[32] This hospital's maternity ward, an alternative route for apprentices who have

neither the time nor the money to study privately with the likes of Le Boursier and her mistress colleagues, used to train women from all over Europe—Sardinia, Denmark, Spain—and of course Parisians, but they are now being turned away in favor of those from the French countryside. This training is of the highest quality. It is an exhausting, intensive, round-the-clock three-month session, presided over by one midwife who devotes herself entirely to this responsibility, living like a nun, dressing modestly, eating with her apprentices—no meat—spending all her nights at the hospital, accepting no tips for deliveries and baptisms, receiving no guests in her room, earning a mere 400 livres a year. The teacher committed to this "assiduous and sedentary" engagement demands that same kind of devotion from her apprentices, of whom she takes only four at a time.[33] These students get extraordinary clinical practice: each year 1,400 to 1,600 women give birth at the Hôtel Dieu, and some nights as many as a dozen deliveries take place.[34] Not only is this education superb and efficient, but it is also a bargain. It costs only 180 livres, and includes the fee for the qualifying examination and certification when the three-month session ends. City apprentices, by contrast, in addition to their lessons, which can cost several hundred livres, must bear the further expense of the grueling qualifying exam.[35] Le Boursier and her Paris colleagues endured the private apprenticeship, but provincial women opt, understandably, for the cheaper, shorter training at the Hôtel Dieu.

There is a problem, however. Even the three-month session in Paris is stressful for many who do not want to be away from home so long. Although provincial wigmakers, valets, coachmen, sculptors, shoemakers, notaries, surgeons, masons, millers, sheriff's officers, and wine merchants from all over France respond to the Hôtel Dieu recruitment program and hasten to sign up their wives, the women themselves are often reluctant. They comply at first with their husbands' bidding but, once inscribed, prove to be unready for the commitment. It is too rigorous and fatiguing. The registers of the hospital's maternity ward make note of these ambivalent pupils: "paid but has not shown up to enroll"; "paid and we have accepted her but she no longer wishes to come"; "paid—we have searched for her—nobody knows where she is"; "does not wish to learn, does not want to come." Some women try to get refunds of their deposit after changing their mind.[36] Obviously this system of

enlistment is not really working. There is more and more talk in high circles of better, alternative ways to train midwives for the provinces. Recently a few regions have employed an experienced Parisian woman to come teach the locals, but the fledgling efforts have been sporadic and there are very few trainees.

Soon a wealthy philanthropic seigneur from Auvergne comes to Paris looking for someone to instruct the peasant women on his estates in the art of childbirth. He may be considering sending one or two of them to study at the Hôtel Dieu, for he feels the situation is urgent. He and his wife make inquiries. Frère Côme seems to know that Le Boursier is restless, that she would gladly reassign her new apprentice to someone else and break free, that she is just waiting for an opening. The quickening pace of intrusion by surgeons into the professional space of midwives has displeased her for some time, but there is apparently more. She wants to leave now . Maybe some private drama has taken place in her life, to which Frère Côme is privy, though we cannot be because all correspondence between him and the midwife is lost. In any case, the monk dissuades the seigneur from looking any further. Once the man hears of Le Boursier in such glowing terms, he will stop at nothing to lure her south to his terres .[37]

Teaching in Auvergne:

The Depopulation Issue

8—

Break to the Provinces:

Thiers-en-Auvergne, 1 October 1751

So eager to make her breakaway, the midwife has left precipitously, arriving in Thiers far ahead of schedule. Nothing is ready. She will have to be put up at the inn for a few days while her residence is prepared.[1] What has made Le Boursier quit Paris in such a hurry, has made her rush to accept this call? Some sudden trauma? A need, building slowly but abruptly felt, to escape from the relentless ritual of city birthing? The wish to test herself? One can cut oneself adrift, take refuge in a journey. It is evidently not hard for her to leave things behind when she has been singled out and summoned for a purpose out of the ordinary. She seems to have lost interest in what is within easy reach; it is as if she has been waiting to spring loose, to be given a challenge, a change, a chance. Indeed, she craves adventure, if her early appearance here is any indication.

The voyage from Paris has taken her along a route that follows the great river valleys, where it can, but that passes through the forests of Fontainebleau and Montargis with their assorted dangers, and bumps along elsewhere over brush-covered, scrubby bogs and rocky hills with an occasional dappled goat. A contemporary guidebook of France classifies only the last part of the trip, south of Moulins, as offering "good roads." This has no doubt been a long, hard journey, the carriage creaking and lurching on these broken routes, but the autumn climate is bracing and the destination lovely and we hear no complaints. Thiers, full of steps and narrow zigzag streets, is situated on a jog of the rollicking Durolle River, which laps at its walls. It is a densely populated commercial center where boats come and go, cleaving the water beside the paper mills and the tilt-hammers where knife blades are forged.[2]

Le Boursier's apprentice back in Paris, having given her teacher 200 livres already, was supposed to pay the balance of her fee, another 100 livres, at Easter of next year, but the midwife has collected it instead on 17 September,[3] and with this early payment has embarked on her travels. She seems to have dutifully made some private arrangement with another midwife to continue teaching the apprentice, perhaps for free; her student does finish her contracted training on schedule and does become a full-fledged Parisian sage-femme in 1753.[4] Meanwhile, Le Boursier turns her back on the capital without apparent remorse, and although she will make numerous trips to this center of power and influence, it will never again be her home. She has walked away from one life to begin another. She has broken free.

Auvergne's intendant, La Michodière, is especially progressive and has for some time been concerned about the perceived depopulation crisis. He is therefore keen to provide his region with good obstetrical care, even corresponding with Voltaire on the matter.[5] As early as 1746 he recruited a Paris midwife, a Madame Berne trained at the Hôtel Dieu, who settled in Riom just north of Clermont, was paid a salary of 500 livres, worked hard, and sang Italian cantatas. The husband of this "gracious lady," however, could not find a satisfactory job, so in short order the family returned to the capital. Next came a Madame Bailly; she lasted five years at her job, but grew to feel she was inadequately recompensed to sustain her ever-growing family, and left at her husband's urging. At the moment of Le Boursier's arrival in Thiers, in nearby Brioude a male surgeon is doing all the deliveries because of the difficulties in keeping Paris-trained midwives in that town. The last one, discouraged, had returned home to her husband, "to the bosom of her family where she could find comfort."[6] For these reasons the Auvergne authorities might be pleased to find that the newest Parisian midwife in their midst is unattached, that she has no husband pulling her away.

Right now Le Boursier is here on a private arrangement. Although the intendant knows of her, she has been invited to Thiers by the local seigneur and philanthropist, Monsieur de Thiers himself. He is vacationing in Tignes, but has alerted his men to her coming. Le Boursier's premature arrival, however, has thrown everything off balance. A Monsieur Merville, judge and journalist in the town, is

trying desperately to smooth the path for her. Almost immediately a conspiracy of surgeons and local matrons forms and vows to undermine the efforts of the new recruit, to treat her as if she came unbidden, to turn the townswomen against her and ensure her ostracism. They experience her presence among them as an invasion, a violation. Merville laments a few days later that already a mother and child have died unnecessarily for stubbornly refusing her services. The new midwife "feels all this, although she doesn't know the extent of it," explains Merville, who believes she will be entirely justified if she, too, chooses to leave the region.

Le Boursier, meanwhile, is watching, listening, taking everything in and learning a great deal. This encounter with blatant hostility is a new experience for her. She handles herself with dignity and restraint, telling Merville that despite all this she is glad to be away from the hustle and bustle of Paris. He, unable to contain his distress, pleads with regional authorities to help him muster support for this "poor outsider, whose merit, spirit of charity, and sound judgment are infinitely touching." Merville works himself into a fury trying to sell the virtues of this highly trained Parisian midwife to his "ignorant" and "undeserving" townsfolk. He contacts the intendant himself, apologizing for the futility of his efforts, and goes on dramatically to despair for the whole unenlightened nation. France is "ungrateful. . . . I thought I knew her. I was wrong, and I swear, she is worse than I dared believe."[7]

If an onlooker is this upset, what is Le Boursier herself thinking? Calm and seemingly unperturbed, she is nonetheless not at all sure she can overcome the obstacles in Thiers. Or that she wants to. But she needs no pity. Shrewdly assessing her chances, she is already sending her papers and recommendations ahead to the much bigger city of Clermont, where the principal mistress midwife has just died. It is a coveted post, and she perseveres. She offers to submit to any new examinations the Clermont surgeons care to give her if her Paris credentials are for any reason insufficient or unacceptable. She volunteers to teach four apprentices.[8] Le Boursier is, instinctively, designing a strategy that will serve her well. Unfailingly gracious to those, like Merville and de Thiers, who appreciate her, she tries not to be discouraged by the others. Far from making anyone regret that some of their efforts on her behalf fail, she commiserates with them about how difficult it is to change habits, to break from old, familiar ways, to overcome inertia. All the while, though,

this energetic woman is doing what she must on the practical front for herself, so that her talents will not go to waste in some obscure backwater of Auvergne. She has not left Paris to molder and fade into oblivion here. A strong sense of self-preservation propels her forward. If supporters, however obliging, are too few or timorous or ineffectual, she will go elsewhere, press on, not squander time reproaching them. She is cut out for nobler ventures. Let other midwives summoned to the provinces retreat to Paris, licking their wounds, seeking tranquillity. No amount of possible peril will deter her; for her there will be no turning back.

Why would she want to go back anyway? The atmosphere in the capital grows increasingly unwelcoming to midwives. The much-anticipated first volume of the Encyclopédie has appeared, and it is the talk of the town. Its article "Accoucheuse" is nothing short of defamatory, quoting the philosopher La Mettrie as saying, "It would be better for women . . . if there were no midwives. I advise . . . to repress these reckless accoucheuses ." The author of the article, a doctor named Pierre Tarin, claims to have gone out of curiosity to watch a sage-femme do a delivery. "I saw there examples of inhumanity," he reports, "that would be almost unbelievable among barbarians. . . . I therefore invite those in charge of watching over disorders in society to keep an eye on this one." The preceding article, "Accoucheur," sums up the prevailing view: "A surgeon delivers better than a midwife." The article "Accouchement," all about childbirth itself, does not even mention midwives at all, and has only men presiding.[9] Demoralizing to be sure for Le Boursier's former colleagues. She is less inclined than ever to look back with nostalgia. Her aim is to move ahead.

Soon she receives a license from the community of master surgeons in Clermont and moves on to that city.[10] She will remain there for the next decade, fashioning and slowly implementing a brave and mighty plan.

9—

"The Stories They Told Me":

Clermont, 9 May 1755

Today at the St. Pierre parish church is the baptism of "Marguerite Guillaumanche, legitimate daughter of François and Aimable Parcou his wife, inhabitants of Talende, born the 4th of this month in

our parish and presented by Helène Desson, midwife, godfather Jean Crouseix, godmother Marguerite Crouseix, inhabitants of this city, who did not sign."[1] Talende is a little town about twenty kilometers due south of Clermont. The parents of this baby were visiting the big city when she was born, but had they come expressly to give birth here or were they taken by surprise? The little girl may well have been premature, for five days have elapsed between birth and baptism, suggesting that the baby was too weak or sickly to be taken to the church until now. The parents, godparents, and midwife are evidently all illiterate, for they cannot put their signatures to the baptismal act.

Le Boursier is nowhere in the picture, evidently not involved in this birth in any way, neither as family member, nor as godparent, nor as presiding midwife, although she has been living, teaching, and practicing in Clermont for four years already. Her surnames bear no resemblance to those of the principals here. She might not even be aware of this event when it occurs. Yet this newborn girl, by some quirk of fate, will become her "niece," will be raised by her, taught by her, and declared her sole heir. Orphaned early, Marguerite Guillaumanche will become the itinerant midwife's only known "family," in one of several acts of self-styling by which, it seems, the midwife finds or invents for herself what life itself has not provided.