I.

Introduction: Image, Space, and Social Values

The image and appearance of the intellectual change along with his society and his particular role in it, for every age creates the type of intellectuals that it needs. We ourselves have witnessed such a change just since the late sixties. That era gave rise to a type of politically and morally activist, left-wing intellectual, who had an impact on public discourse and protest far beyond the borders of classroom and campus, a type that is now dying out, along with his characteristic features, from the unconventional, working-class clothes to his manner of speaking and general lifestyle. Our consumer- and leisure-oriented society has spawned its own replacements for the sixties intellectual: the apolitical "moderator"; the entertainer; the analyst and prognosticator, who spots new trends or may even be employed to try to create them. The partisan critic and reformer is no longer in demand, rather the commentator who is himself essentially conformist and unaffiliated.

This new breed of intellectual also looks very different from his predecessors, often assimilating the clothes and manners of the dynamic and successful entrepreneur or media mogul, with whom he in fact happily associates. Most, however, are indistinguishable from the average businessman and probably share a similar income and image of themselves as "specialists." In short, their image reflects, in equal measure, both how they see themselves and the role they play in society.

But regardless of his specific role—the disaffected critic and provocateur, the educator, or the sympathetic and popular entertainer—every society needs intellectuals and cannot do without them. It gives

rise to the particular type it needs most at any given time: prophets and priests, orators and philosophers, scholars, monks, professors, scientists, commentators, media experts, filmmakers, and museum curators. We need them to shape the mood and opinions of the public, to invent the concepts, visual imagery, and styles that are the prerequisites for a social dialogue. We need them as much to plan a party as a revolution, to dissent and criticize but also at times to rule and govern.

I trust the reader will not expect from a humble archaeologist a precise definition of the concept 'intellectual'. I use the word simply as a convenient shorthand, in order to avoid having to repeat such cumbersome formulations as "poets and thinkers, philosophers and orators." Neither the Greeks nor the Romans recognized "intellectuals" as a defined group within society. Such a sense of group identity seems to have arisen for the first time within the context of French intellectuals' involvement in the Dreyfus affair.[1] Nevertheless, as in most other societies, prophets, wise men, poets, philosophers, Sophists, and orators in Greco-Roman antiquity did consistently occupy a special position, both in their own self-consciousness and the claims they made for themselves, and in the influence and recognition they enjoyed. Of course, the roles they played were very different in the two cultures. Even so, it seems to me legitimate to inquire into the image of the intellectual in a given period, from the point of view of claims made and recognition accorded, as well as, more broadly, that period's attitude toward intellectual activity.

As an archaeologist, my primary interest is in the specific visual images—votive and honorific statues, grave monuments, and portrait busts—not with the far larger and more complex problem of self-identity as conveyed in literary sources (for example, the inspiration of the poet by the Muses or the ideal of the philosopher-king). My subject is the intent and effect of the image within the parameters of, on the one hand, a given era's collective norms and values and, on the other, the expectations of the subject and the patron for whom the work was made. Instead of a long theoretical disquisition, a brief look at some examples from more modern times may help clarify my purpose.

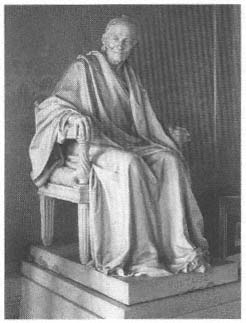

Fig. 1

Voltaire by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1781).

Paris, Comédie Française.

The Modern Intellectual Hero

Jean-Antoine Houdon's portrait of Voltaire (fig. 1), from 1781,[2] is perhaps the most celebrated monument of a European intellectual of the moderm era. It shows the subject, who had died two years before, seated on an "ancient," thronelike seat, wearing a philosopher's robe and the "wreath of immortality" in his hair. Thus did Houdon himself characterize Voltaire, who had sat for his portrait shortly before his death. The statue combines in extraordinary fashion the intellectual lucidity and physical frailty of the aged Voltaire with his own apotheosis. The monument was originally intended to stand in the Académie Française, not only to commemorate Voltaire himself, but as testimony to the self-conscious pride of the Academy membership. The

statue of Voltaire celebrates the Enlightenment as the highest moral and spiritual authority, and the leaders of the Enlightenment here lay claim to a position of authority in the state and society. They set the philosopher, in the guise of Voltaire, on a throne—not just any throne, but an ancient one, as an ancient philosopher. In this way classical antiquity is invoked to legitimate the self-conscious political claims of the intellectual élite. Needless to say, no ancient philosopher ever sat on a throne.

It was, by contrast, an entirely different complex of values and necessities that inspired nineteenth-century Germany to honor its culture heroes in a veritable cult of statuary. After the wars of liberation in German lands had brought neither political freedom nor national unity, the citizenry began to seek in cultural pursuits a substitute for what they still lacked. For example, they erected monuments to intellectual giants, usually at the most conspicuous location in the city, an honor that until then had been reserved for princes and military men. These monumental statues were planned and executed by local and national committees and associations, and their unveiling was accompanied by dedication ceremonies and even popular festivals. There arose a true cult of the monument, which included broadsheets, picture books, and luxury editions of "collected works." With all this activity, the Germans began to see themselves, faute de mieux, as "the people of poets and thinkers."

This is especially true of the period of the restoration and, in particular, the years after the failed revolution of 1848, when monuments to famous Germans, above all Friedrich von Schiller, sprouted everywhere. These statues were not just objects of veneration amid national pride but served the populace as models of citizen virtues with which they could identify. The great men were deliberately rendered not in ancient costume, and certainly not nude, but in contemporary dress and exemplary pose.

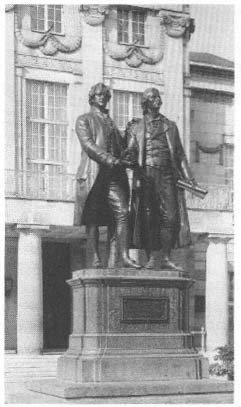

Perhaps the most famous of these monuments—and the one considered most successful by people of the time—was the group of Goethe and Schiller by Ernst Rietschel, set up in 1857 in front of the theater in Weimar (fig. 2). A fatherly Goethe gently lays his hand on the shoulder of the restless young Schiller, as if to quiet the overzealous

Fig. 2

Monument to Goethe and Schiller by Ernst

Rietschel (1857). In front of the theatre in Weimar.

passion for freedom of the younger generation. The relationship of the two poets (which in reality was somewhat problematical) is thus stylized into a symbol of authentic German male bonding, a classical paradigm and standard of conduct for the citizenry.[3]

It is, however, no accident that the statue bases on which the poets stand are just as high as those of princes and rulers. We gaze up to them from the drudgery and confusion of daily life. "There is something higher than the daily routine,"[4] namely, the everlasting works of po-

etry and art, in which we can find consolation and edification. Although born of political disappointment, these monuments erected by the bourgeoisie in no way represent a call to political action, not even the Schiller monuments of the postrevolutionary period. On the contrary, they attest to an implicit attitude in which the political has been sublimated in favor of pragmatic citizen virtues. This process was facilitated by the fact that the great Weimar poets were in the service of the court and, like many other successful intellectuals of the time, proudly displayed the honors and medals bestowed by the prince.[5]

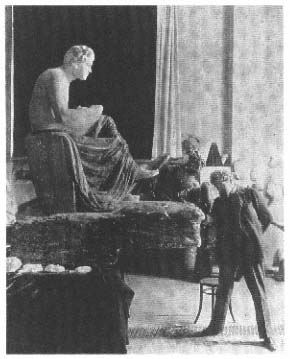

In the late nineteenth century, the cult of the monument spread throughout Europe. But the poets, musicians, and artists who are thus honored are turned into solitary, superhuman figures before whom posterity can only kneel in awe and wonder. The earlier images of the fellow citizen realistically depicted in contemporary dress give way to a new vision of giants and titans, nude in the manner of the antique. Statues like Rodin's Victor Hugo or Max Klinger's somewhat later Beethoven (fig. 3) render the apotheosis of the great mind in such exaggerated form that, not just for modern taste, it verges on the ridiculous. Contemporary reaction was also divided, unlike in the preceding period.[6] The French poet in his exile resists the reactionary storm breaking over his country, depicted as mighty waves threatening him in his rocky seat. The German composer, on the other hand, in his heroic detachment, is utterly divorced from the present. This is a remarkably complex cult statue that reflects more the feverish imagination of its creator than the beliefs of his contemporaries.[7]

Beethoven is enthroned high up on a kind of rocky outcrop, solitary and half-naked. The mighty eagle at his feet makes the allusion to Zeus obvious. But this hero, despite his vigorous pose, determined expression, and clenched fist, is not a ruler. Originally Klinger wanted a line fromn Goethe's Faust carved on the rock: "Der Einsamkeiten tiefste schauend unter meinem Fuss." Scenes from classical and Christian mythology are represented on the exterior sides of the throne, including the Crucifixion of Christ, the Birth of Venus, Adam and Eve, and the family of Tantalus. The great genius sees the unity of the world that is hidden from others. His music is a kind of religious revelation, and in this role as prophet he becomes a god himself. That this is truly the

Fig. 3

Max Klinger at work on his monument to

Beethoven (1902).

message intended is confirmed by the circumstance that Klinger carried out his work on the statue for many years without a commission, at enormous personal cost in expensive materials, and, when it was finished, wanted to have it displayed in a specially built cult place. (This was in fact done, first in the exhibition of the Vienna Secession and later in the museum at Leipzig.)

The creator of this gigantic vision, however, withdrew to play the role of priest in the cult. Like most artists and writers of this period, Klinger deliberately cultivated a bourgeois image and appearance. He had himself photographed, wearing the proper suit, with his titanic statue. He is just another adorant of the "immortals." There is a deep divide between the present and the great men of the past, who, with

their works, hover above contemporary life like guiding stars, unattainable and unwavering, like spiritual revelation. The educated look up to them and derive sustenance from them. They enhance the quality of our leisure time but otherwise deliver no categorical imperatives, like the earlier monuments of the artist as model citizen. Art and life had become completely separate realms. Appropriately, many of the later monuments were not displayed in city squares, but rather in parks and public gardens, put there as part of local beautification campaigns.[8]

I shall resist the temptation to pursue this line of inquiry and develop a full typology of the imagery of intellectuals in the modern era. These few examples were intended simply to illustrate my approach and the kinds of questions I wish to pose. Each of the three, almost randomly chosen, instances that I have dealt with could easily find a parallel among the portraits of Greek intellectuals that would be in one way or another equivalent. But this would not get us very far, for when we look closely, the historical framework is as different as the portraits themselves. The point I wish to stress most is that in both cases a successful interpretation is utterly dependent on how well we can reconstruct the specific context in which a particular portrait was created and displayed. As with modern portraits, we have to ask where the monument was set up, who commissioned it, and what circumstances obtained in a particular society. Specifically, what value was attached to intellectual activity, and what was the relationship between society at large and the individual intellectual or group of intellectuals? In light of the extremely fragmentary and incomplete nature of the evidence, as will shortly become clear, it is much easier to pose these intriguing and, in recent years, increasingly fashionable questions than to answer them.

Archaeologists have thus far dealt with the material at our disposal from this perspective either in very restricted instances or not all. Positivist scholars, who laid the groundwork over a century of intensive and detailed scrutiny, concentrated primarily on problems of identification and dating. The culmination of this approach is Gisela Richter's admirable 1965 corpus The Portraits of the Greeks, in which the portraits

are ordered chronologically according to when the subjects lived, rather than when the portrait type was created, as if the goal were to produce a set of photographs for a modern Who's Who . Those scholars who were more interested in the content of the portraits have devoted themselves almost exclusively to questions of the "character" and "spiritual physiognomy" of each individual and have sought in the portraits a reflection of spiritual and intellectual qualities. Chief among these is Karl Schefold, whose book Die Bildnisse der antiken Dichter, Redner und Denker of 1943 is the only study that deals with the most important portraits of Greek intellectuals in chronological order.[9]

What makes my approach different from Schefold's is that my focus is not on the figure of the individual intellectual, but rather on the position and image of intellectuals as a class within a particular society and the changes we can detect in periods of transition from one era to the next. What I propose is a history of the image of the intellectual in antiquity. For this reason I shall proceed basically chronologically, even though much of my text retains the essaylike flavor of the lectures on which it is based. Nevertheless, I believe this method has a certain distinct methodological advantage, given the problems of identification that beset so many portraits. That is, even anonymous portraits and those that can be dated only approximately retain their interest as evidence for the question of general attitudes within a given period. In most instances it matters less who is represented than how he is represented—though admittedly it is frustrating to acknowledge that even in the case of some portraits of evidently key figures we are still groping in the dark.

Roman Copies, or Through a Glass Darkly

Regrettably, we cannot move directly from these preliminary remarks to the subject at hand without a brief detour to consider what I call the foggy mirror in which we must view much of the portraiture of ancient intellectuals. It is a fact that almost all portraits of the great Greek poets and thinkers are known to us only in copies of the Roman

period. This means that each individual case is open to difficult, sometimes insoluble problems of reconstruction, analogous to the philologist's textual criticism. I will spare the reader in the present context a long excursus on the methods of so-called Kopienkritik .[10] But it is a fundamental principle of any historian that before he can use his primary sources and evaluate their importance, he must ask why and for what purpose they were created in the first place.

In our case, this question leads us straight to an essential chapter in the history of the image of the intellectual. These copies served specific purposes for the Romans that had nothing whatever to do with their original function as honorific statues in the agora or dedications in sanctuaries. For the Romans they functioned as the icons in a peculiar cult of Greek culture and learning, a topic I shall pursue in some detail later in this book. For the moment, let us just cast a critical eye on these copies, in consideration of their usefulness for the reconstruction of the lost original.

Since the Romans were primarily interested in the faces of the famous Greeks, which they believed they could "read" in the same way as modern critics do, they usually had only the heads copied. Of course such a bust or herm was also cheaper than a life-size statue and took up less space.[11] But Greek artists had produced only full portrait statues, into the Late Hellenistic period, and for the Greeks, from Archaic times on, the true meaning of a figure was contained in the body. It was the body that expressed a man's physical and ethical qualities, that celebrated his physical and spiritual perfection and beauty, the kalokagathia of which we shall presently have more to say. The most important qualities transcended the individual person, for the function of the portrait statue was to put on display society's accepted values, through the example of worthy individuals, for a didactic purpose. Personal and biographical details were of lesser importance.

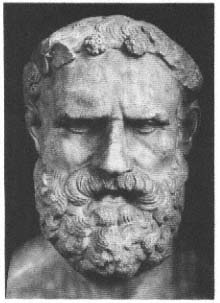

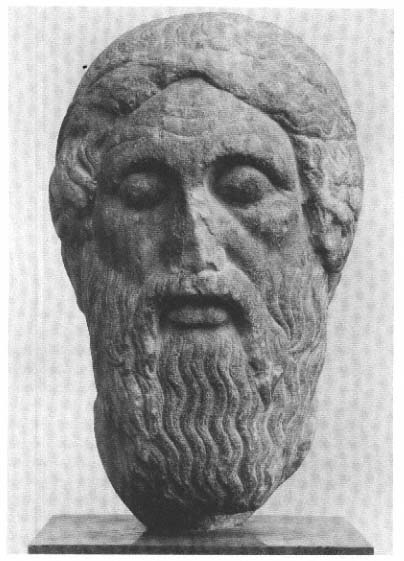

The portrait bust, which largely shaped the reception of Greek portraiture in the Roman Empire, arose first only in the course of the Hellenistic period.[12] Just one example may serve to illustrate how much is lost in this reduction to only a head, and what problems and uncertainties it creates for a proper interpretation. How are we to interpret the vigorous expression of this High Hellenistic portrait of a

Fig. 4

Head wreathed in grape leaves,

of the same type as the old singer in

fig. 79. Paris, Louvre.

poet, preserved in several herm copies (fig. 4)? What kind of a body should we imagine went with such a head? Would we ever have guessed that this is the expression of an impassioned singer, moving in rapt emotion to the music, as we now know thanks to the chance discovery of an almost fully preserved statue (cf. fig. 79)?

A further problem is the reliability of Roman copies of the heads. The issue is not only one of the competence of the sculptor, but of the level of interest, or lack of interest, on the part of the original buyer. There were passionately cultivated Romans who sought in such statues conversation partners, who used them, as Seneca says, as incitamenta animi (Ep. 64.9–10). These individuals presumably wanted carefully detailed sculptures of high quality, but that does not necessarily mean the same thing as faithful copies. The knowledgeable Roman patron had his own preconceptions of the Greek subject and was looking for

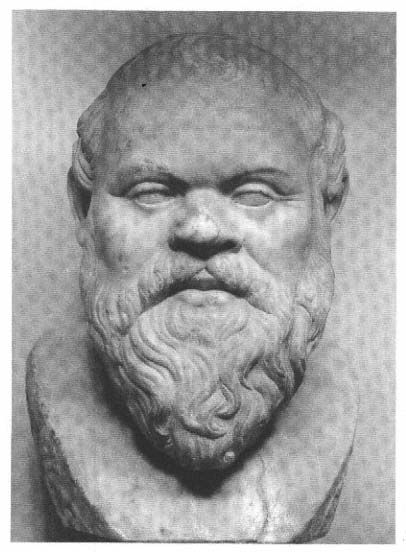

Fig. 5

Socrates. Roman copy of a Greek

original of ca. 380 B.C. (Type A).

Naples, Museo Nazionale. (Cast)

Fig. 6

Socrates. Post-antique bronze cast after

a now lost Roman copy of the same

Greek original as fig. 5. Munich, Glyptothek.

the kind of "talking head" that would reveal something of the subject's character and work. The obvious solution was to take a face that did not seem expressive enough and embellish it, if necessary with physiognomic detail. We may see a good example of such embellishment in the finest of the copies of the earliest Socrates portrait, an Early Imperial bust in Naples (fig. 5). Only recently has a careful comparison with other copies of this type revealed that the gentle smile that distinguishes this face must be an innovation of the copyist, an attempt to "humanize" the Silenus features and, perhaps, to suggest a touch of irony. A bronze head in the Munich Glyptothek, however, seems to provide a reliable rendering of the original face (fig. 6). And yet the head is probably not even ancient, but rather a modern cast of a now lost Roman copy! This is, admittedly, an extreme case, but it does illustrate some of the constant perils we face in the study of Greek portraits and their transmission.

Fig. 7

Pindar. First-century B.C. copy

of a statue of ca. 460 B.C. Oslo,

National Gallery.

Fig. 8

Pindar. Second-century A.D. copy

of the same type as fig. 7. Naples,

Museo Nazionale.

In addition, the prevailing tastes of each period could play a considerable role. Since, for example, Augustan art did not look kindly on wrinkles, and youthful faces were the order of the day, the portraits of Menander made at this time were beautified in the same way as those of the emperor and his fellows. In the case of Menander, if we did not have more subtle copies from other periods, we would be ignorant of certain essential features of the original. By contrast, the last decades of the Roman Republic valued above all faces with emphatic physiognomic traits. For the copyists, this meant heads with extra wrinkles and more expressive faces. A striking example is the portrait of the poet Pindar (d. 446 B.C. ) that has only recently been identified. A very detailed copy of the first century B.C. in Oslo probably exaggerates the original's features of old age and adds a realistic quality to the flesh and skin texture unknown in the period when the portrait was created (fig. 7). An equally finely worked head in Naples (fig. 8), on the other

hand, assimilates the poet so fully to the style of the Hadrianic period, especially in the eyes and facial expression, that one could take it at first glance for a likeness of one of that emperor's contemporaries.[13]

But it was the lack of interest on the part of Roman patrons that took a far greater toll on quality and fidelity to detail. Perhaps no group of Roman copies can claim as many examples of hasty workmanship and poor quality as the portraits of the Greeks. The chief culprits are serial and mass production. Portrait herms were often displayed in villa gardens lined up in long galleries. They were simply part of the decorative scheme of wealthy homes, like the furniture, completely divorced from any cultural interests the owner may have had. There were even instances where hundreds of such herms were arranged alphabetically, providing nothing more than a visual dictionary of Greek learning. Phrases carved on the herm shaft—a snatch of poetry, a saying of the philosopher, or even a quick biographical sketch—served as mnemonic devices for rudimentary education (cf. p. 208).[14] In these circumstances, obviously, quality and detail were of secondary importance, and even the names and quotations on the herms could get mixed up. But the most grievous loss that results from this mode of transmission is any secure information on the specific location of the original portrait, its setting, and the occasion for which it was put up.

But I do not want to belabor this bleak situation any further. Rather, I propose to show, in three detailed case studies, how, in spite of the unpromising state of the evidence, we can indeed reach some secure answers to the question of context posed earlier. These examples belong to the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and thus are among the earliest portraits that we have. In view of the meagre amount of material preserved, we can hardly come to any general conclusions. But in each of these three instances we shall encounter certain features that turn out to have a general applicability to the study of the portraiture of Greek intellectuals.

Wisdom and Nobility: An Early Portrait of Homer

Of the earliest known portrait type of Homer, a life-size statue created about 460 B.C. , only copies of the head are preserved.[15] The form of

Fig. 9

Homer. Early Imperial copy of a portrait of ca. 460 B.C. Munich, Glyptothek.

the body is unknown, as are location, patron, artist, and occasion. Nevertheless, we can still reconstruct some sense of the conceptual framework of this portrait type. A subtly carved head in the Glyptothek in Munich (fig. 9) of the Early Imperial period seems to give a reliable copy of the original. Its fidelity is confirmed by two other, less finely worked examples, which in turn enable us to spot the divergences in the remaining copies.

The sculptor imagined Homer as a blind old man, turned slightly to one side and listening to his own inner voice. Old age does not carry negative connotations here, as so often in Greek poetry. Signs of decrepitude in the cheeks, temples, and the deeply sunken eyes are indicated with the utmost discretion. This Homer is a handsome old man—kalos geron —full of dignity. This is best expressed in the long, carefully arranged hair and lush, well-tended beard, as well as other features of the physiognomy, such as the full lower lip. Above all, the treatment of the locks of hair on the brow contributes to this impression of beauty and nobility.

The hair is carefully arranged over the skull and held in place by a band or fillet, while on the sides and in back it falls freely in thick locks. The bald pate that is typical of the iconography of old men is, in addition, concealed by a complicated arrangement: two broad strands are drawn from the crown forward and knotted over the brow. This both calls attention to the subject's baldness and at the same time artfully hides what might detract from his beauty. Similarly, the long locks on the sides are intended to mitigate the sunken cheeks.

That this arrangement of hair over the forehead is a realistic feature, a hairstyle that men actually wore, is confirmed by a vase painting of ca. 510–500 B.C. , in which Priam wears strands of hair similarly knotted over his bald head (fig. 10). This must be a fashion for old men of the Late Archaic period, which reflects in turn the negative associations of old age and its effect on the body. The aristocrat tries to conceal the less attractive features of the aging process.[16] This particular Late Archaic coiffure was probably out of fashion by the time the portrait of Homer was made, thus characterizing him as a distinguished older man of an earlier generation. We are reminded of the noble old men who advise their king in Greek tragedy.

Fig. 10

Hector arms for battle; at his left, his aged father,

Priam. Red-figure amphora by Euthymides, ca. 500

B.C. Munich, Antikensammlungen.

The notion of Homer's blindness is an old one, first attested by the sixth century (Hymn. Hom. Ap. 172). The model for it is most likely the portrayal of the blind singer Demodokos in the Odyssey (8.62ff.). Even before that, the figure of the blind singer was widespread in Egypt and the Near East. Perhaps this conception arose from a common experience of early civilizations, that the blind often had unusually good memories, a talent that made them useful.[17] In the portrait, however, blindness is not presented so much as a biographical detail, but as a prerequisite for the poet's extraordinary memory and wisdom. Just as the closed eyes are charged with meaning and more than just a realistic touch, so too the lines in the brow signify more than just age. Their strict parallelism looks rather emblematic and probably alludes as well to the poet's prodigious powers of memory. It is surely no coincidence that the same lines appear on the brow of the old seer lost in meditation from the east pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.[18]

True knowledge is ancient knowledge. The composing of verse is conceived in this portrait as a gift from the gods, akin to that of the

seer, a form of revelation. Greek mythology is full of seers and poets whose powers are directly connected with their blindness. This is true, for example, of Demodokos, the singer at the court in Phaeacia,

whom, the Muse loved above all other men, and gave him

both good and evil; of his sight she deprived him, but

gave him the sweet gift of song.

(Od. 8.63–65, trans. R. Lattimore)

The prophetic power of the blind is generally considered as a kind of compensation. The great seers like Teiresias and Phineus went blind because they had seen the gods, because they knew too much and revealed their knowledge to men. But blindness is more than a punishment or destiny. It sharpens the other senses, especially the power of memory, and thus for some authors becomes a prerequisite for particular transcendental gifts. According to a saying of the Delphic oracle, memory is "the face of the blind."[19] This apparently reflects a widespread belief. The philosopher Democritus was said to have blinded himself so that his spirit would not be distracted by the outside world.[20] By emphasizing Homer's blindness, the artist celebrates above all a wisdom that derives from unsurpassed powers of memory.

But how should we imagine the lost body that went with this head? The nearly upright position of the head, on which all the best copies agree, suggests a standing rather than a seated figure. Based on the standard iconography of old men in this period, he must have been either leaning on a staff, the attribute of the elderly and especially the blind (Soph. OT 455), or at least holding one in his hand.[21] The Late Antique poet Christodoros, ca. A.D. 500, seems to have seen just such a statue of Homer in the Baths of Zeuxippos in Constantinople:

He stood there in the semblance of an old man, but his old age was sweet, and shed more grace on him. He was endued with a reverend and kind bearing, and majesty shone forth from his form. . . . With both his hands he rested on a staff, even as when alive, and had bent his right ear to listen, it seemed, to Apollo or one of the Muses hard by.

(Anth. Gr. 2.311–49)[22]

A statue of this type is in fact known, though in a version of the fourth century B.C. , from a copy found in the gardens of the Villa dei Papiri, which might allow us to associate the portrait of Homer with a similar body.[23] Unsure of his step because of his blindness, he would have supported himself on the staff and, in so doing, turned his head ever so slightly to the right, away from the viewer. This very expressive turn of the head is well preserved in several of the copies. That is, the poet stands directly facing the viewer and yet remains fixed in his own world.

On the question of who put up the original statue and where, we can only speculate. But as luck would have it, the earliest attested statue of Homer belongs to the same period as our original, and Pausanias, who mentions it in his description of the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia (5.24.6, 5.26.5), also provides some helpful information on its context. About 460 B.C. Mikythos, a well-known Sicilian statesman who had served as regent for the children of the tyrant Anaxilaos in Rhegion and Messana and subsequently emigrated to Tegea in the Peloponnese, made dedications at Olympia of unheard-of proportions, for the recovery of his son. This included a group of at least twenty statues by the sculptor Dionysios of Argos, displayed at a prominent spot north of the great temple.[24] The poets Homer and Hesiod apparently stood alongside the Olympians and other gods, including Asklepios and Hygieia. Their location by the gods can best be interpreted to mean that Homer and Hesiod are the messengers of the gods, who mediate between them and mankind, a sentiment also expressed in a well-known passage of Herodotos: "It was Homer and Hesiod who created a genealogy for the gods, who gave the gods their epithets, allotted them their honors and responsibilities, and put their mark on their forms" (2.53).

This interpretation is also supported by the fact that Mikythos' dedication included a statue of the mythical singer Orpheus as well. He stood like a prophet beside the statue of his divine patron Dionysus, whose mysteries had been associated with the so-called Orphic Hymns since the sixth century.[25]

Even though our portrait type is certainly not to be identified with the Homer in Mikythos' dedication, which was under-life-size, at

least it provides us some notion of where and in what context a statue of Homer could be set up in the fifth century, that is, in a sanctuary, along with other statues, as part of a dedication that expressed certain concerns and intentions of the dedicator. In the case of Mikythos, his son's illness may not have been the only motive. No doubt this recent émigré to mainland Greece managed to call attention to himself in spectacular fashion by making a dedication of such outsized proportions. The very fact that the two poets were so prominent in the group says something about the importance of such figures in Greek society of the time.

In this connection, the "realism" of the Homer portrait also takes on some significance. He is not like those images of mythical old men in vase painting or even the seer from Olympia, who, despite bald head and white hair, have an ageless and idealized face. Rather, Homer's face is marked by a new kind of physical immediacy, not so much in its individual traits, but as the face of a typical old man who is at the same time an individual, with protruding cheekbones, sharply arched brows, sagging flesh, furrows, and wrinkles. Along with contemporary likenesses of Themistocles and Pindar, he is among the very earliest Greek portraits.[26] This new kind of portraiture brings Homer out of the distant past and into the present.

In this light, we might imagine that such a portrait, especially one displayed in a conspicuous public place like the dedication of Mikythos, was meant as a conservative response to the enlightened criticism of men like Xenophanes, who spoke out not only against the agonistic values of the aristocracy, but against traditional religious piety associated with Homer.[27] In any case, a portrait like this surely implies the recognition accorded the sophia that poets and thinkers had claimed for themselves. In this same period, in Athens, Aeschylus' Eumenides brought him the status of political and religious commentator, even a kind of theologian of the city.[28]

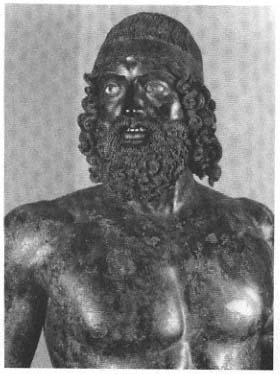

It is astonishing that a society like that of the Greeks in the sixth and fifth centuries, which so glorified youthful vigor, should have accorded the ultimate spiritual and religious authority to the figure of a decrepit old man. We should keep in mind that in a sanctuary like Olympia such a portrait statue would have stood not far from divine and heroic statues like the Riace Bronzes (fig. 11). The juxtaposition

Fig. 11

Bronze statue of a hero found in the sea at

Riace. Greek original ca. 450 B.C. Reggio

Calabria, Museo Nazionale.

of two such antithetical statues must have intensified the contrast, the unbounded glorification of youth and strength in a warrior or athlete set against the wisdom of age and corporeal frailty. The polarity of these images exemplifies the diversity and vitality of Greek culture. Finally, in this Homer are the roots of the extraordinary portraiture of aging philosophers of the Hellenistic period.

The reconstruction of the statue of Homer and its possible context are of course too vague and speculative to be conclusive. The question of where the actual statue stood simply cannot be answered.[29] But this example has at least demonstrated that even a single relatively faithful copy can offer new insights, when we focus on the question of con-

text. And that it is often better to ask unanswerable questions than to ask none at all.

In the Greek imagination, all great intellectuals were old. The portrait of Homer stands at the beginning of a long tradition that reaches to the end of antiquity. There exists no portrait of a truly young poet, and certainly not of a young philosopher.

Anacreon and Pericles

Our second example also involves the statue of a poet, but of a very different kind. In his description of the Athenian Acropolis, which he visited in the 170s A.D. , Pausanias mentions a statue of the poet Anacreon east of the Parthenon:

On the Athenian Acropolis is a statue of Pericles, the son of Xanthippus, and one of Xanthippus himself, who was in command against the Persians at the naval battle of Mycale. But that of Pericles stands apart, while near [plesion ] Xanthippus stands Anacreon of Teos, the first poet after Sappho of Lesbos to devote himself to love songs, and his posture is as it were that of a man singing when he is drunk.

(1.25.1)[30]

The statue of Pericles stood near the Propylaea and not far from the Athena Lemnia, a location intended to remind the viewer of Pericles' accomplishments as a statesman. Tonio Hölscher has rightly supposed that father and son were deliberately not placed together in order to avoid the impression of an undemocratic concentration of power in one family. The proximity of the statues of Xanthippus and Anacreon has been explained on the basis of a friendship between the two, though the evidence for this is uncertain.[31]

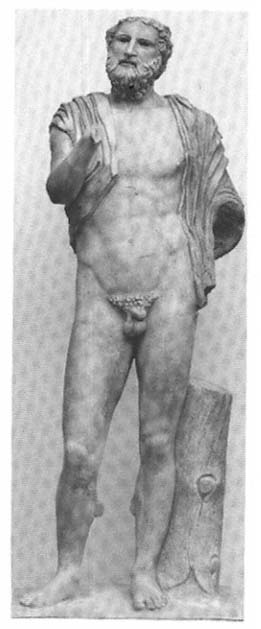

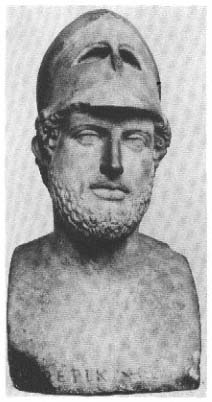

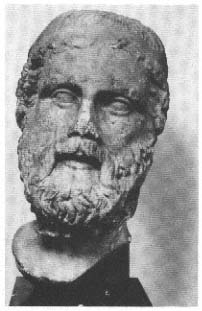

Of the statue of Pericles only copies of the head are preserved, while we know nothing whatever of the statue of Xanthippus. Thanks to one of those rare strokes of archaeological fortune, however, a statue found in the ruins of a Roman villa near Rieti gives an almost complete copy of the statue of Anacreon (fig. 12).[32] An inscribed herm copy of the same type secures the identification. That this is indeed

Fig. 12

Anacreon. Roman copy of a bronze

statue ca. 440 B.C. Copenhagen, Ny

Carlsberg Glyptotek.

the portrait seen by Pausanias is very likely, though, as often, incapable of definite proof. Pausanias' emphasis on the proximity of Anacreon's statue and that of Pericles' father suggests that the two were somehow connected. The statue of Anacreon can indeed be dated stylistically to the period when Pericles was in power, and probably originated in the circle of Phidias, who played such a major role in Pericles' Acropolis building program. It is only logical to assume that we are dealing with a dedication of Pericles or his immediate circle, as has often been thought.

But why would Pericles, of all people, at the height of his power, have wanted to honor posthumously this friend of aristocrats and tyrants, who first came to Athens and the court of the Peisistratids aboard an official trireme sent for him by the tyrant Hipparchus on the death of Polykrates of Samos, and had died at Athens a full two generations earlier at the ripe old age of eighty-five? Why should democratic Athens, on the eve of the Peloponnesian War, honor a poet associated above all with extravagant banquets and drunkenness (cf. Ar. Thesm. 163; Kritias, in Ath. 13.600E), the very embodiment of the soft and unmanly Ionian way of life?[33] Any answer to these questions must come from the statue itself.

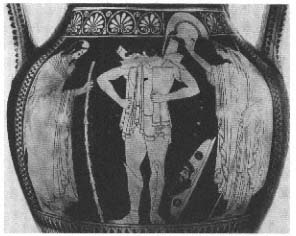

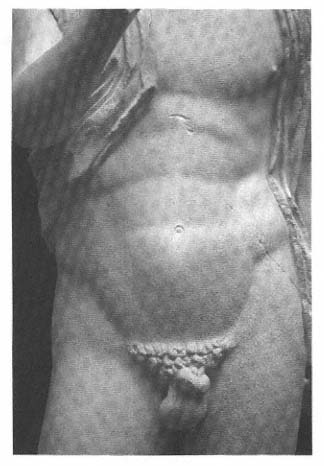

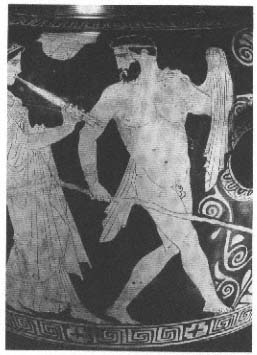

The poet is singing and playing a stringed instrument, the barbiton . His enthousiasmos is best expressed by the way the head is slightly thrown back and turned to the side. The drunkenness, however, is indicated only very discreetly. Only when we set him beside other statues of the time, with their firm stance, are we aware of a slight instability of Anacreon, especially in a side view.[34] The poet is presented as a participant at a merry symposium, rather than as a poet as such. Hence also his nudity, the short mantle thrown over the shoulders, and the fillet in his hair, all elements of the iconography of Athenian male citizens, as we see them on countless red-figure vases, taking part in the symposium and subsequent komos . Singing and playing the barbiton are also characteristic of these drunken revelers.

Anacreon's contemporaries about 500 B.C. had in fact depicted him on vases as an older, bearded man in a long robe, dancing, and playing, surrounded by exuberant young revelers. Sometimes he wears a flowing mantle and the Ionian headgear that would later be mocked as

Fig. 13

Three revelers in elegant Lydian dress. Column krater, ca. 470–460 B.C.

Cleveland, Museum of Art. A. W. Ellenberger Sr. Endowment Fund, 26. 599.

effeminate—in the company of older revelers also clad in this exotic "Lydian" costume, including parasol, earrings, and pointy shoes. In the early fifth century, older Athenians did evidently still wear such outfits at komos and symposium (fig. 13), as a gay reminder of the good old days of their youth under the tyrant Peisistratus and his sons.[35] In any event, to judge from these vases, Anacreon was already during his lifetime a representative of the soft Ionian way of life and the uninhibited drinking party.

The image of the drunken singer is also the basis for the statue of Anacreon, though with a significant alteration. Unlike the vase painters, the sculptor shows the poet nude, with a handsome, ageless physique. Only the unusual length of the beard and fullness of the frame might be subtle hints of advancing age.[36]

A comparison with the well-known vase painting of Sappho and Alcaeus confirms that Anacreon is indeed depicted in the guise of a

Fig. 14

Sappho and Alcaeus on a krater or wine

cooler by the Brygos Painter, ca. 470 B.C.

Munich, Antikensammlungen.

symposiast and not as poet or professional singer (fig. 14). Alcaeus wears the long, flowing robe characteristic of singers and flute players and looks intently at the ground as he sings. (The painter has indicated the singing with little bubbles issuing from his mouth.) Sappho turns to him in admiration, attesting to the effect of his song.[37] This is, incidentally, one of our very few depictions of a female poet.

Anacreon is presented as the restrained and in every sense exemplary symposiast, quite unlike the uninhibited revelers, Anacreon himself among them, of Late Archaic vase painting. Drunkenness and ecstasy are hinted at with great discretion. The garment, is carefully arranged over the back and in front barely moves. The face shows no more emotion than the well-known contemporary portrait of Pericles

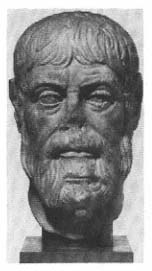

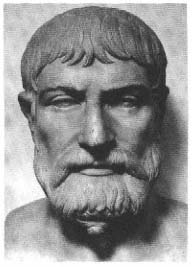

Fig. 15

Pericles. Herm copy of a bronze statue

ca. 440 B.C. London, British Museum.

Fig. 16

Anacreon. Early Imperial copy of the same

statue as fig. 12. Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

(figs. 15, 16). The point of this is clear: even on this jolly occasion the singer never loses his composure, and shows himself to be the very image of a model citizen of High Classical Athenian society, when it was none other than Pericles himself who set the standard of behavior. We may recall the stories of Pericles' conduct in public, and especially the tradition about his solemn, immobile countenance, which never registered joy or pain but lost its masklike composure only at the death of his youngest son (Plut. Per. 36; cf. 5).[38]

The head of a slightly earlier (though probably not Attic) statue of

Pindar may give some indication of the range of possibilities for facial characterization in this period (cf fig. 7).[39] Pindar is shown with the deeply wrinkled face of an older man, his strained expression best understood as a sign of intellectual activity. At the same time, as Johannes Bergemann has pointed out, the old-fashioned and carefully stylized beard could be meant to associate the poet with the conservative and luxury-loving aristocratic circles for whom he composed his verse. Such biographical traits are entirely possible in this period, as we can also see, for example, in the statue of an elderly poet who rushes off with an energetic stride, evidently toward a specific goal. Even if this figure has thus far resisted interpretation, it is nevertheless clear that we are once again dealing with a specific biographical element.[40]

Just as Pindar has a look of severity and concentration, so we might well have expected for Anacreon an expression of gaiety and delight. Instead, Anacreon's face is so fully devoid of emotion that, in a copy that omits the characteristic turn of the head, we might easily have mistaken him for a king or hero.[41] Such was the determination of the sculptor to emphasize the subject's exemplary behavior, just as in the portrait of Pericles.

The way the mantle is draped actually emphasizes the poet's nudity and calls attention to a striking detail that has barely been noticed before: he has tied up the penis and foreskin with a string, a practice known as infibulation (or, in Greek, kynodesme ) (see fig. 17). The explanations for this practice in ancient authors—as a protective measure for athletes or a token of sexual abstinence in a professional singer (Phryn. PS 85B; Poll. 2.4.171)—all come from relatively late sources and are not satisfactory in the present instance.[42] But many examples of kynodesme in contemporary vase painting (fig. 18) suggest another explanation. Here it is almost exclusively symposiasts and komasts who have their phallus bound up in the same manner as Anacreon, and as a rule they are older men, or at least mature and bearded. Satyrs are also so depicted, evidently for comic effect.[43] To expose a long penis, and especially the head, was regarded as shameless and dishonorable, something we see only in depictions of slaves and barbarians.[44] Since in some men the distended foreskin may no longer close property, allowing the long penis to hang out in unsightly fashion, a string could be

Fig. 17

Detail of the statue of Anacreon in fig. 12 showing kynodesme .

used to avoid such an unattractive spectacle, at least to judge from the evidence of vase painting. The vases also make it clear that this was a widely practiced custom. We may then consider it a sign of the modesty and decency expected in particular of the older participants in the symposium. Once again, in the ideology of kalokagathia , aesthetic appearance becomes an expression of moral worth.

The borrowing of this detail from the world of Athenian daily life

Fig. 18

Symposiast with his penis bound up.

Stamnos by the Kleophon Painter, ca. 440

B.C. Munich, Antikensammlungen.

lends a realistic element to the nude figure. This Anacreon is no longer the representative of an extravagant and decadent bygone way of life. He becomes instead a contemporary, whose conduct at the symposium is a model of restrained and proper enjoyment. By underlining his nudity, the statue celebrates the perfection of the body, just as those of younger men. This Anacreon is a handsome and distinguished man, a kaloskagathos . In the Athens of this period, when the Parthenon was going up, it is hard to understand a statue like this as anything other than an exemplar of correct behavior, expressing precisely what Thucydides puts in the mouth of Pericles in his famous Funeral Oration (2.37, 41), the praise of Athens for its festivals and enjoyment of life;

thus the statue is a vision of the perfect citizen. In Athens, physical exercise and military training are not part of a hardened and joyless way of life, as in Sparta; rather, they are part of the pleasures of a free and open society.[45]

For all the iconographical similarities between Anacreon and the komasts in vase painting, we should not forget that the same image, when isolated and magnified to the scale of a life-size portrait statue, takes on a very different public character and meaning. Only in this context does it become the exemplar of certain social values. In fact in this period, the symposium was becoming less popular as a subject for vase painting, and the symposiasts themselves are mostly depicted behaving rather modestly and properly, as if following the model of Anacreon.[46]

When the Athenians saw Anacreon, the poet of the celebration, beside the great general Xanthippus, they had before them two prototypes, together representing the twin ideals of Athenian society that blend so harmoniously in Pericles' vision. We might note, however, that the Corinthian envoys at Sparta accuse the Athenians of being just the opposite (Thuc. 1.70). Because of their fierce ambition and nationalism, "they go on working away in danger and hardship all the days of their lives, seldom enjoying their possessions because they are always adding to them. Their idea of a holiday is to do what needs doing." Whether or not such charges were made in reality, and whether justified or not, one thing is clear: the honoring of Anacreon, the poet of the symposium, at this location, in this form, and at this point in time must surely have had a programmatic character. The statue proclaims that gaiety and enjoyment are as much a part of the superior Athenian way of life as sports and warfare, and that life was as pleasurable and happy in this new age of Periclean democracy as it had been in the old days of the tyrants and their "Lydian" decadence.[47]

Whether my interpretation is entirely correct or not, this posthumous statue of Anacreon stood for a very specific set of values. That is, its purpose was less to celebrate an individual famous poet than to be the embodiment of a certain social ideal: the poet as exemplar. In principle this would still be the case if the statue had instead been put up by the opposition camp, the oligarchs.[48]

Socrates and the Mask of Silenus

This third case study is an example not of the confirmation of collective norms, but of their denial, in paying honors to Socrates, who in life had so provoked and annoyed his fellow citizens with his questioning that they finally condemned him to death in 399 B.C. The earliest portrait of the philosopher originated about ten to twenty years after his death and shows him in the guise of Silenus. In flouting the High Classical standard of beauty so blatantly, this face must have disturbed Socrates' contemporaries no less than his penetrating questions.[49]

Starting with the influential circle of intellectuals around Pericles and the enormous success of the Sophists, there arose in Athens a tension between society at large and this new breed of intellectual, who exercised such great influence on political, religious, and moral thought.[50] We find traces of this tension in the parodies of Sophists in Old Comedy and even in vase painting. In both media, this ridicule targets bodily and aesthetic deficiencies. Such parody would seem to be the origin of a strategy, later employed so effectively by certain philosophers, such as the Cynics, of having themselves portrayed old and ugly or with unconventional appearance as an act of provocation. As in many cultures, the Greeks tended to dismiss the unpopular, the marginalized, and the dissident as physically defective and ugly. Their prototype is the ugly, bandy-legged Thersites (Il. 2.212ff.), in whom the Cynics would later, appropriately enough, take an interest. For the Greeks, this kind of ridicule was from the very beginning a form of social discrimination and moral condemnation, for in the ideology of kalokagathia a man's virtues and his noble heritage were expressed in the physical perfection of his body.

The earliest "portrait" of Socrates, in Aristophanes' Clouds of 423 B.C. (101ff., 348ff., 414; cf. Birds 1281f.), makes fun of his appearance.[51] Like his pupils, he is pale and thin from strain and deprivation, dirty and hungry, with long hair. Indifferent to his own appearance, he parades through the city barefoot, staring people down and trying out his corrupting intellectual experiments on them. It has long been recognized that this description of Socrates' physical appearance is as much a conventional topos as the caricature of his supposed teachings.

Fig. 19

So-called Aesop on a red-figure cup,

ca. 440 B.C. Rome, Vatican Museums.

Fig. 20

Caricature of a Sophist debating

(?). Red-figure askos, ca. 440

B.C. Paris, Louvre.

In any event, the starving thinker of the Clouds has little in common with the fat-bellied teacher with the face like a Silenus mask described by Socrates' own pupils Plato and Xenophon. Rather, it is a common stereotype, which we find occasionally in caricatures of "intellectuals" in vase painting.

On a small red-figure askos,[52] for example, of ca. 440 B.C. , a naked, emaciated little man with an enormous head leans far forward on his slender staff and seems to be simply lost in contemplation. Just so, we are told, Socrates could stand still for hours, concentrating on a problem (fig. 20). The vase probably caricatures one of the leading thinkers of the day. The creature's bare skull, swelling out in all directions, seems about to burst with all the profound thoughts churning inside it. He is nevertheless an Athenian citizen, and not a member of one of those categories of inferiors like slaves or barbarians, as we can infer from the characteristic pose of resting on the staff and short mantle.

The same is true of another example of a comical thinker, again with emaciated body and oversized head, who has always been identified in the scholarship as the writer of fables, Aesop (fig. 19).[53] With furrowed brow and open mouth, he listens carefully to the teachings of the fox sitting before him. He has pulled his mantle tightly around

his meagre body, as if he were shivering. Like Aristophanes' Socrates, he is ugly, with long hair, bald head, and unkempt, scraggly beard, and is clearly uncaring of his appearance.

These modest vase paintings probably convey some idea of the general antipathy that greeted the new breed of intellectual giants of Periclean Athens, on which Aristophanes could draw for his caricatures. Too much thinking and intellectual exercise are not for good, upstanding people: they make you strange and an object of ridicule.

The historical Socrates, from all that the ancient sources report, must have been strikingly ugly. But in this he was surely not alone among the Athenians. That his unfortunate appearance became such a focus of attention must derive from the offensive nature of his intellectual activities. The likening of Socrates to silens, satyrs, and Marsyas, as we hear from Plato and Xenophon, probably originated with his enemies and detractors, for the particular traits that are usually mentioned in the comparison—the squat figure with big belly, broad and flat face with bulging eyes, the large mouth with protruding lips, and the bald head—were all considered, by the standards of kalokagathia, not only ugly, but tokens of a base nature (Cic. Tusc. 4.81).[54] The decision to adapt the comparison with Silenus for a portrait statue intended to celebrate the subject, however, presupposes a positive interpretation of the comparison, such as we do in fact find, in particular, in the speech of Alcibiades in Plato's Symposium . Perhaps Socrates himself had already laid the groundwork for this new interpretation by accepting the comparison with his characteristic irony.

The copies of the head from this portrait statue convey very different nuances, though on all major elements of detail they are in agreement (fig. 21). That is, they all follow the basic analogy with Silenus iconography, especially in the flat, strangely constricted face, the very broad, short, and deep-set nose, the high-set ears and bald head, and the long hair descending from the temples over the ears and the nape of the neck (fig. 22). But at the same time, a comparison with images of the actual Silenus leaves no doubt that in Socrates the silen features have been at least partly mitigated.[55] This is particularly true of the eyes, the well-groomed beard, the hair, which, though long, is ex-

Fig. 21

Bust of Socrates (as in fig. 5). Naples, Museo Nazionale.

Fig. 22

Silenus on a silver coin from

Katane in Sicily, ca. 410 B.C. Berlin,

Staatliche Münzsammlung.

tremely carefully coiffed, and the full but well-formed lips. There is in addition probably a hint of introspection that can be detected in most of the copies. These positive features are the more remarkable in that literary descriptions emphasize Socrates' bulging eyes, swollen lips, and unkempt hair. Evidently the intention of the statue's patrons was to tone down the Silenus comparison by combining it with unmistakable features of propriety, to make an unambiguously positive statement. Furthermore, the Silenus mask of this portrait is a countenance artfully constructed of prescribed iconographical formulas. In real life, Socrates' ugliness might have been of an entirely different nature.

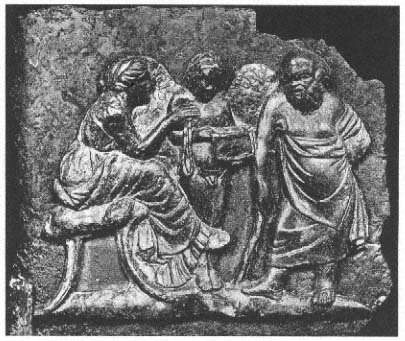

What sort of body could have been combined with this head? The loss of the body is especially frustrating in light of the complex associations of the head. It seems most unlikely that such a head could have sat on a perfectly handsome and conventional body, like that of the later portrait statue of Socrates (cf. fig. 33). An unimpressive bronze relief from Pompeii (fig. 23), about fifteen centimeters in height, made as a furniture appliqué, may give us a rough idea of the lost statue.[56]

The scene, known in a number of versions, is itself an eclectic pastiche of several prototypes, made by a Late Hellenistic artist, and probably depicting Socrates' initiation into the mysteries of love by Diotima. The figure of Diotima is based on the Tyche of Antioch. For the

Fig. 23

Socrates and Diotima. Bronze relief from Pompeii, first century B.C.

Naples, Museo Nazionale.

figure of Socrates, the artist has used a motif, standard in vase painting from the late sixth century on, of a man relaxing on his staff with the other arm casually propped on his hip. The motif appears occasionally as late as on Attic grave stelai of the fourth century, but not in the Hellenistic period. This would imply an early date for the prototype, unless we prefer to think of a historicizing invention. The motif expresses the qualities of leisure and delight in conversation that were such important elements of the ethos of Classical Athens. It marks the Athenian citizen who is not gainfully employed but has long stretches of free time in which to stand around discussing all that is going on in the city. Even the Eponymous Heroes on the Parthenon Frieze are represented in this manner.[57] This image of Socrates would thus be that of the properly behaved citizen, but at the same time, as in the

portrait head, with unmistakably ugly and deviant features—the small stature and bulging belly—just as described in our literary sources.

But we have yet to ask why the statue's patrons accepted in the first place an image of Socrates' ugliness, one that likened him to the semi-human followers of Dionysus best known for their indecent and drunken ways. And why above all in Athens, where all deviations from the ideal body were apt to be eliminated in art, as a glance at the countless Classical Attic gravestones will remind us?

There is surely more than one aspect to the comparison of Socrates to Silenus. In being likened to a mythological creature, he is presented as an extraordinary human being, transcending conventional norms. The old Silenus, unlike the rest of his breed, was considered the repository of ancient wisdom and goodness and for this reason appears in mythology as the teacher of divine and heroic children. As early as about 450 B.C. a vase painting shows Silenus with his citizen's staff in the role of the watchful paidagogos .[58] The connotation as the wise teacher was thus an obvious one for the portrait of Socrates-as-Silenus.

But the Silenus analogy does more than just pay homage to Socrates as the remarkable teacher; it presents a challenge as well. The deliberate visualization of ugliness represented, in the Athens of the early fourth century, a clash with the standards of kalokagathia . That is, a portrait like this questioned one of the fundamental values of the Classical polis. If the man whom the god at Delphi proclaimed the wisest of all could be ugly as Silenus and still a good, upstanding citizen, then this must imply that the statue's patron was casting doubt on that very system of values. We have to look at this statue of Socrates, with its fat belly and Silenus face, against the background of a city filled with perfectly proportioned and idealized human figures in marble and bronze embodying virtue and moral authority.

Such doubts can have originated only in the circle of Socrates' friends. It was long ago suggested that the statue might have been intended to stand in the Mouseion of Plato's Academy, founded in 385, where we know a statue of Plato himself, put up by the Persian Mithridates and made by the sculptor Silanion, later stood (D. L. 3.25). We may perhaps go even a step further and consider a possible connection between the concept behind the statue and an element of Platonic

thought contained in the very passage of the Symposium that compares Socrates to Silenus. The discussion there revolves around the contrast between interior and exterior. between appearance and reality. Socrates himself, it is suggested, is like a figure of a flute-playing Silenus (evidently a familiar object, perhaps of wood), which, when you open it, contains a divine image (Symp. 215B). True philosophy recognizes the "seemingness" of the external and leads instead to the perception of actual being. Socrates' body may be seen as an exemplar of these precepts, for the seemingly ugly form conceals the most perfect soul. This idea implies that the entire value system of Athenian society is built upon mere appearance and deception, misled by its fixation on the external form of the body.

Seen in this light, the portrait of Socrates makes a rather forceful and provocative statement and becomes a kind of extension of Socratic discourse into another medium. As the living Socrates once did, the statue now challenges his society on a fundamental principle of its identity.[59] We are witnessing here the discovery of a new dimension in the portraiture of the intellectual, one that will not be exploited again until the philosopher statues of the Early Hellenistic age.[60]

In the next chapter we shall see how this rigid value system, founded upon the principles of kalokagathia and conformity, persisted for more than a full half century, at least in the public sphere of the Athenian city-state, and even managed to bring about a transformation in the provocative image of Socrates.