5

The Temporal Order

The Solar Cycles

While the inner vision of the shaman surely showed the way to the essential truth for those who shaped the spiritual thought of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica through the centuries of its development, these speculative thinkers went far beyond their Siberian shamanic forebears in drawing out the mythic, philosophic, and theological implications of that vision. The shamanic world view posited a cosmos governed by an underlying spiritual order growing out of the mythical spiritual unity of all things which both caused and explained the myriad, seemingly disconnected "facts" of the material world, but the causes and explanations characteristic of the prototypical shamanism of the hunting and gathering peoples of Siberia were mystically simple and direct, those perceived by and applicable to the individual in a small group. The spiritual thought of Mesoamerica gradually evolved from that shamanic base into an intricate, subtle, and complex depiction of the revelation of the spiritual order of the cosmos in the world of man. Still apparent in the now centuries-old fragments of that highly developed thought is the sense of wonder with which those inquisitive minds responded to the indications of inherent orderliness which the shamanic vision allowed them to see in the seemingly chaotic world confronting them.

That wonder, as we shall see, is often expressed through the use of the mask as a metaphor for the way in which the harmonious vitality of the life-force underlies the chaotic life of the world of nature. The metaphor of the mask suggests that the natural world, the "mask" in this case, not only covers the animating force of the spirit but also expresses its "true face." Thus, the natural world was seen as symbolic, as pointing, in a way understood by the initiated, to the underlying harmony of the spirit. Those who understood the symbols of the mask could "read" its meaning; the false face became the true face in much the same way the donning of the ritual mask allowed the wearer to express his "true" inner spirit. Although this underlying order was suggested by many kinds of natural "facts," nowhere was it clearer to the seers of Mesoamerica than in the regularity of the numerous cycles through which time seemed to move. Nothing drew their attention more powerfully than this cyclic time; its regularity must have seemed to them nothing less than the force of life itself, the spiritual essence of the cosmos at work. Through the understanding of those cycles, the Mesoamerican sages could figuratively remove the mask of nature, which in all other ways covered the workings of the spirit, and get at the thing itself.

The clearest, and no doubt the first recognized, evidence of this cyclic regularity was apparent in the movement of the sun. That the sun's movement should provide the key to unlock the mysteries of the cosmos makes sense in two quite different ways. First, the most apparent regularity in the external world of nature is provided by the sun's daily rising and setting around which human beings have always organized their lives as it bears an organic relationship to the rhythmic cycle of sleep and waking built into their own bodies. To this organic regularity, however, the shamanistic cultures of Mesoamerica added a second way of seeing the significance of that daily cycle. The endless alternation of day and night no doubt seemed the natural counterpart of and the perfect metaphor for the dualistic nature of the cosmos they envisioned. The presence of the sun during the day must have seemed naturally to represent the waking world of daily existence, sentient activity, logical thought, and physical life. The absence of the sun at night represented the complementary oppo-

site, sleep, which replaced the sentient activity of the daytime world with the fantastic imaginings of dreams, mental rather than physical activity, and the temporary and highly symbolic "death" of the waking person. The daily movement of the sun thus divided the natural world in the same way man felt himself to be divided: into matter and spirit, visible and invisible, living and dead. Tied to the sun's movements, man alternated between his waking, "real" self and his sleeping, dreaming, "spirit" self. This dichotomy within man's very nature, of course, is the same one expressed in the split masks, half-living and half-skeletal, found in Preclassic burials in the Valley of Mexico (pl. 52) which clearly image forth a shamanistic view of life and death as parts of an endless cycle, parts that exist in actuality or in potential at all times. Just as the ability of the shaman to enter the world of death at will suggests the unity of the two states, so the cyclic alternation symbolized by the sun's movement unified those opposed states. That cycle, then, could be seen as an expression of the mystic order of the spirit that alone could make comprehensible the seemingly anarchic diversity of earthly life.

In addition to this daily solar regularity, Mesoamerican thinkers early became aware of and fascinated by the other cycles of the sun. They charted the annual movement of sunrise and sunset along the horizon which resulted in the equinoxes and solstices and noted the regular coming and going of the two instances of the sun's zenith passage each year. The solar cycles were so basic to the concept of time throughout Mesoamerica that among the Maya, for example, the word for sun, kin, also means both day and time.[1] In fact, the day, the most obvious unit of time measured out by the sun, was the smallest unit of time measured in Mesoamerica and was the fundamental unit on which the Maya constructed all the other cycles of time with which they were concerned.[2] The Toltecs and other later groups in the Valley of Mexico saw the solar year as the basic unit, perhaps because their northern origins made them more concerned than the Maya with the annual cycle of seasonal change.[3] The significant fact, however, is that a unit derived from solar movement was used throughout Mesoamerica as the foundation of an elaborate calendrical system designated to chart and understand the force of the spirit as it worked in the natural world.

That such solar observation is of great antiquity in Mesoamerica and that its practice continued with the same intensity until the time of the Conquest (and, in fact, is still practiced by some contemporary Indian groups) can be seen in both the archaeological and written record that survived the Conquest. The great ceremonial centers constructed by the various cultures of Mesoamerica as focal points of the ritual through which they interacted with the natural and supernatural forces of the cosmos were, from the earliest times, laid out on the basis of horizon sightings of solar positions and often contained structures that were designed or oriented to make precise solar and other astronomical observations for ritual purposes. In the Maya Petén, for example, the early pyramid Structure E-VII Sub at Uaxactún

was the western point in group E from which sunrise was observed on the east, marked by three small temples. These temples were aligned on an eastern platform in a north-south line; their northern and southern locations were determined by sunrise at the summer and winter solstices, whereas the location of the central temple was set by sunrise at the equinoxes. . . . Thus Str. E-VII Sub was the viewing point in a solar . . . observatory.[4]

Built during the late Preclassic, this complex served as a model for "at least a dozen sites within a 100 kilometer radius of Uaxactún"[5] and indicates the early importance of solar observation among the Maya. In the Valley of Oaxaca, according to Anthony Aveni, the curiously shaped structure called Mound J built during Monte Albán I (ca. 250 B.C.) was probably used to sight the star Capella, which was used as an "announcer star" for the "imminent passage of the sun across the zenith." The passage could then be observed using a vertical shaft bored into a subterranean chamber aligned with Mound J.[6] Structures similarly suited to astronomical observation of significant moments in the various cycles of the sun are found throughout Mesoamerica. The best known is probably the Caracol at Chichén Itzá, and others have been found at such sites as Mayapán, Uxmal, Paalmul, and Puerto Rico.[7] Significantly, most of the structures probably related to solar observation are ornamented with huge stucco or mosaic masks that seem to denote the importance of the structures and to suggest their role in the solar observation that uncovered the spiritual order of the universe and in the ritual activity through which man harmonized his existence with that universal order.

Such structures were used in laying out the ceremonial centers of which they were a part, and the "cross petroglyphs" found at Teotihuacán evidently served the same purpose there. These markers consist of two concentric circles centered on a cross, the design indicated by a series of holes pecked into a stucco floor or rock. The first such petroglyph was found in a building next to the Pyramid of the Sun, and others were subsequently found at locations suggesting their use by the architects of Teotihuacán to determine the baselines of the grid pattern strictly adhered to throughout the centuries-long construction of the city. The location of the petroglyphs and the resulting location of the baselines indicate that the grid was oriented according to horizon sightings of celestial phenom-

ena related to solar cycles.[8] This solar connection can also be seen in the design of the petroglyph, a quartered circle, found in many contexts and variations throughout Mesoamerica, most of which refer to cycles of time, generally solar cycles.[9] These other symbolic uses of the design suggest that the cross petroglyphs of Teotihuacán were more than surveyor's base marks. They were, symbolically, the order of the city and the order of the cosmos, which it was intended to replicate. As we demonstrate below, they referred directly to the meeting place at Teotihuacán of the worlds of spirit and matter. Just as the rising and setting of the sun on the horizon symbolically denoted that meeting, the line of the cross petroglyph representing the sun's course was bisected by a line perpendicular to it, a line creating the universally symbolic cross designating the center of the universe.

That intersection of the central axis of the universe with the earthly plane marks the point at which the shamanic movement between the worlds of matter and spirit is possible. Hence, the cross petroglyph and the city itself must be seen as symbolic constructions placed on the earth so as to reveal the underlying spiritual order, an order seen most clearly in the essentially spiritual annual cycle of the sun from which the quartered circle was derived.[10] Seen in that way, the cross petroglyph and the city are "masks" placed on material reality, not to cover it but to reveal its spiritual essence—precisely, of course, the function of the shamanistically conceived ritual mask throughout Mesoamerican history. Similar petroglyphs used for the same purpose have been found at widely scattered sites from Zacatecas to Guatemala, most of which had been influenced by Teotihuacán,[11] suggesting the fundamental importance of that symbolic use of the solar cycles as the very fact of diffusion indicates the significance of the design to the people employing it. The structures of ceremonial centers throughout Mesoamerica, then, both in their siting and functions demonstrate the fundamental concern of the builders with the ways in which the regularity of solar movement betrayed the order inherent in the spiritual underpinnings of the natural world.

Further evidence of the concern of Mesoamerican thinkers with the regularities of the cycles of the sun can be seen in the calendrical systems that must have existed well before the Preclassic. The full extent of that calendrical system, one unsurpassed in intricacy and complexity, will be discussed below, but a significant part of the system was, as we would expect, a solar calendar. Made up of 360 days divided into eighteen "months" of twenty days with five "unlucky" days added to complete a 365-day cycle, it was called the xihuitl in central Mexico and the haab by the Maya and provided one of the foundations of the larger calendrical systems. Evidence from Oaxaca suggests it was already in use in the early Preclassic. [12] And we also have evidence of the early existence of one of these larger systems. Called the long count, it computed dates from a presumably mythical starting point corresponding to 3113 B.C. (according to the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson correlation), dates that were recorded on monuments by the Maya and before them by the Olmecs, the probable originators of the system.[13] A number of those dates suggest the antiquity of this elaborate system, among them the date on Stela 2 at Chiapa de Corzo which corresponds to 36 B.C., that of Stela C at Tres Zapotes corresponding to 31 B.C., and the date on the Tuxtla Statuette which corresponds to A.D. 162.[14] Obviously, the systematic solar observations on which the original solar calendar and its elaborate variations were founded must have begun in remote antiquity and been dutifully continued until the Conquest with the numerous dates and calculations of early times no doubt written on perishable materials such as wood, skin, and bark paper. Were these to have survived, they would have testified to the ancient and enduring Mesoamerican fascination with the connection between the regular movement of the sun and the orderly progression of time.

The written evidence that does survive in the codices, the screenfold painted books used for a variety of divinatory and pedagogical functions by the priests and shamans of the various pre-Columbian cultures, suggests in several ways the importance the recording of data related to the solar cycles had in the latter stages of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican development. Many of the Mexican codices contain solar calendars charting the movement of the year through the regular succession of the veintena festivals, the great ritual feasts that ordered the movement of time by denoting the end of each of the eighteen twenty-day periods of the solar year. Fittingly, then, the sun ordered the ritual life of the cultures of central Mexico, a ritual life designed to harmonize man's existence with the life-force symbolized by the sun. The few surviving codices of the Maya are astronomical in nature and offer a rather different sort of testimony to the importance of the sun and its cycles to Mesoamerican spiritual thought as they contain a great deal of astronomical information regarding the cycles of the moon and Venus as well as tables used to predict the possibility of eclipses, all of which were related to solar movement.

Thus, the written evidence of pre-Columbian thought coincides with the evidence from the archaeological record to indicate clearly that the various cycles of the sun were seen throughout Mesoamerica as embodying the spiritual order of the universe. They revealed a unity at the heart of all matter and the way in which the spiritual force emanating from that mystical unity operated in the world of nature. Rather than imagining a god

separate from his creation, the thinkers of Mesoamerica conceived of the divine as the life-force itself, constantly creating, ordering, and sustaining the world.

That force, embodied in and exemplified by the cycles of the sun, not only symbolized the workings of the spirit as it ordered the universe through the magic of time but was also the creator of life, a creation also linked metaphorically to the solar cycles. The sun, as a symbol of the mystical life-force, was seen as the source of all life, a cyclic source that made creation an ongoing process rather than a unique event.

Far from imagining a sure and stable world, far from believing that it had always existed or had been created once and for all until at last the time should come for it to end, . . . man [was seen] as placed, "descended" (the Aztec verb "temo" means both "to be born" and "to descend"), in a fragile universe subject to a cyclical state of flux, and each cycle [was seen] as crashing to an end in a dramatic upheaval.[15]

This cyclic process of creation and destruction is recorded in the pan-Mesoamerican myth cycle of the Four (or Five) Suns which identifies each stage in the ongoing process of creation as a sun, one stage in a solar cycle. The basic myth is simple; in its Aztec version, the present age, that of man and historical time, is the Fifth Sun. The first of the four preceding periods, the First Sun, identified by the calendric name 4 Océlotl, or 4 Jaguar, saw the creation of a race of giants whose food was acorns. That age ended with their being devoured by jaguars, often a symbol of the night sky and thus the dark forces of the universe. The Second Sun, 4 Ehécatl, or 4 Wind, peopled by humans subsisting on piñion nuts, ended with a devastating hurricane that transformed the people who survived it into monkeys. This age was associated with Quetzalcóatl in his aspect of wind god, Ehécatl. The Third Sun, 4 Quiáhuitl, or 4 Rain, was naturally associated with Tlaloc and had a population of children whose food was a water plant. It was destroyed by a rain of fire from the sky and eruptions of volcanoes from within the earth with the surviving inhabitants changed into turkeys. The Fourth Sun, 4 Atl, or 4 Water, was populated by humans whose food was another wild water plant. It was destroyed by floods, as its association with Chalchiúhtlicue, the goddess of bodies of water, would suggest. The survivors of the destruction appropriately became fish. The present world age, the Fifth Sun, 4 Ollin, or 4 Motion, is destined to meet its end by earthquake.

This basic myth, so clear and direct on the surface, is fascinating in its subtle interweaving of the shamanistic idea of the life-force with the Mesoamerican conception of the solar cycles as representative of the inherent order of that essentially spiritual life-force. Both the daily and annual cycle of the sun are basic to the myth's conception of creation. The concept of five successive suns suggests the diurnal cycle of the sun with the awakening of life in the morning of each day and the "death" of life at day's end, a suggestion emphasized in the destruction of the First Sun by the jaguar, a symbol of the night. Just as awakening from sleep provides a model for creation, so the "awakening" of plant life in the spring provides another basic metaphor suggested by the care with which the myth specifies the sustenance provided for humanity in each of the world ages; it is always a plant that springs from the earth itself to provide nourishment. Thus, the earth functions as a repository of the life-force, which is "awakened" by the solar cycle in the spring in order to create the life that in turn sustains human life. The significance of the sun is underscored by the identification of corn in the present world age as the divine sustenance of humanity, suggesting at once the Indian's almost mystical reverence for that grain and the process of growing it, the reciprocal relationship between humanity, nature, and the gods, and the relationship between the life cycle of the individual plant and the sun, a connection that pervades the mystical attitude toward corn in the mythologies of Mesoamerica. The myth of the Five Suns thus directly involves the cycles of the sun in the generation of life on the earthly plane by the life-force that lies at the heart of the universal order.

But the solar cycles are only part of a larger conception of creation. Life in the Fifth Sun is created by Quetzalcóatl from bones and ashes of the previous population which he was able to gather during a shamanlike journey to the underworld, the hidden world of the spirit entered only through a symbolic death to the world of nature. The shamanic nature of this creation is further suggested by the metaphoric reference to the belief that the life-force in the creatures of this earth resides in the bones, the "seeds" from which new life can grow. To create that life, Quetzalcóatl pierced his penis and mixed the blood resulting from that autosacrificial act with the pulverized bone and ash from the underworld. Symbolically, his creative act unites the shamanistic belief that the bones are the repository of the life-force with the Mesoamerican view that blood represents the essence of life, a view especially clear in this case since the blood is drawn from his penis, the source of semen, man's reproductive fluid. Creation is seen in a series of organic metaphors bringing together seeds and bones, the sun and birth, man and plants in a complex web of meaning suggesting the equivalence of all life in the world of the spirit, which underlies and sustains the world of nature. Life in this world, the myth suggests, must be understood in terms of that underlying spirit.

The evidence we have of Maya thought reveals a remarkably similar cyclic conception. In the

Popol Vuh , the mythic history of the Quiché Maya of highland Guatemala, the creation of life, or "the emergence of all the sky-earth," is described as

the fourfold siding, fourfold cornering,

measuring, fourfold staking,

halving the cord, stretching the cord

in the sky, on the earth,

the four sides, the four corners.

In other words, a quadripartite creation

by the Maker, Modeler,

mother-father of life, of humankind,

giver of breath, giver of heart,

bearer, upbringer in the light that lasts

of those born in the light;

worrier, knower of everything, whatever there is:

sky-earth, lake-sea.[16]

Attempting to create man, the gods three times formed creatures incapable of proper worship; only on the fourth try were they successful. First, birds and animals were created, but they could not speak to worship their creators "and so their flesh was brought low"; they were condemned thereafter to be killed for food. The second attempt resulted in men made from "earth and mud," but it was equally unsuccessful because they had misshapen, crumbling bodies; their speech was senseless so that they, too, were incapable of the worship required by their creators. After destroying these men, the gods next fashioned "manikins, woodcarvings, talking, speaking there on the face of the earth," but their speech was equally useless because "there was nothing in their hearts and nothing in their minds, no memory" of their creators. These manikins were destroyed by a flood and the combined efforts of the animals, plants, utensils, and natural objects they had ungratefully used. Those surviving the destruction became the present-day monkeys.[17]

Following this third unsuccessful creation, the Popol Vuh narrates the lengthy exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque in the underworld, exploits comparable in mythic function to Quetzalcóatl's shamanic descent into the underworld in the cosmogony of central Mexico (significantly, one of the meanings of Quetzalcóatl is "Precious Twin"). Following those exploits, historical man, the Quiché, was created from the life-giving corn and thereby linked to the annual seasonal cycle. "They were good people, handsome," and "they gave thanks for having been made." But this time the gods had succeeded too well. These men were godlike: they could see and understand everything. In order to put them into their proper relationship to their makers, "they were blinded as the face of a mirror is breathed upon. Their eyes were weakened. . . . And such was the loss of the means of understanding, along with the means of knowing everything, by the four [original] humans."[18]

Although neither the account in the Popol Vuh nor the similar account in The Annals of the Cakchiquels, the neighbors and enemies of the Quiché Maya, suggests the eventual destruction of the present world age, there is a reference to such a destruction by Mercedarian friar Luis Carrillo de San Vicente, who said in 1563 that the Indians of highland Guatemala believed in the coming destruction of the Spaniards by the gods, after which "these gods must send another new sun which would give light to him who followed them, and the people would recover in their generation and would possess their land in peace and tranquility."[19] This belief indicates the close similarity between the cycles of the Maya cosmogony and those of central Mexico. Miguel Le6n-Portilla points out that essential similarity when he writes that for the Maya, "kin, sun-day-time, is a primary reality, divine and limitless. Kin embraces all cycles and all the cosmic ages. . . . Because of this, texts such as the Popol Vuh speak of the 'suns' or ages, past and present."[20] Robert Bruce makes that idea even clearer. The Popol Vuh, he says, consists of "the same cycle running over and over," and that cycle is "the basic cycle, the solar cycle [that] pervades all Maya thought."[21] Thus, both the Popol Vuh and the Aztec myth depict a reality grounded in the spirit whose essential order is revealed by the cycles of the sun. It is no wonder that throughout Mesoamerica even today, Indians who think of themselves as Christians identify Christ, whose death allowed him to enter the world of the spirit, with the sun as the very epitome of the spirit as it moves in the world of nature.

The Mesoamerican fascination with the sun is further shown by the fact that insofar as the thinkers of Mesoamerica were interested in other celestial bodies, they were almost exclusively interested in those whose cyclic movements were apparently related to the sun. Thus, the two other bodies most often of concern were the moon and Venus. In view of the important role the moon plays in many mythologies, it perhaps seems strange that, as Beyer observed, the moon played a relatively "insignificant role in the mythological system encountered by the conquistadores."[22] Two myths from central Mexico at the time of the Conquest indicate clearly that whatever importance the moon had derived from its role in a predominantly solar drama.

The first of these myths depicts the creation of the current sun and moon shortly after the beginning of the present world age. In one of its versions, two gods—Nanahuatzin, poor and syphilitic, and Tecciztécatl, wealthy, handsome, and boastful—volunteer to throw themselves into a great fire in a sacred brazier which will purify and allow them to ascend as the sun and light the world. Tecciztécatl proves too cowardly to leap, but Nanahuatzin does and rises gloriously as the sun. Following Nanahuatzin's success, Tecciztécatl musters

his courage, immolates himself, and becomes the moon. True to his boastful nature, Tecciztécatl at first shines as brightly as the sun, but the remaining gods throw a rabbit in his face (what European culture sees as the image of an old man on the face of the moon was seen throughout Mesoamerica as a rabbit) to dim him to his present paleness.[23] In addition to the obvious oppositional relationship of the sun and moon—one the ruler of the day sky, the other of the night; one bright, the other pale; one retaining a consistent shape, the other changing—this myth suggests other oppositions that would have been of particular importance to the Aztecs, who saw themselves as the people of the sun, a warrior sun who symbolically led their nation. Nanahuatzin, ugly and disfigured on the surface, embodied the inner virtues they prized: courage, modesty, dedication; Tecciztécatl, superficially handsome and seemingly brave, was actually a cowardly braggart. The myth finds reality beneath the surface of appearances, and the fact that this truth is contained in a myth concerned with the creation of the sun and moon is amazingly appropriate as the sun and its various cyclic movements, including the cycle in which the moon participates, provided an understanding of and a metaphor for the underlying order of the cosmos for the Mesoamerican mind. As the myth suggests, the inner truth is most significant; one must look beneath the surface of reality in this more profound sense to understand the essential meaning of the world of appearances.

The second myth also delineates the basic opposition between the sun and moon within the cycle of day and night. Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec tutelary god, was said to have been conceived by Coatlicue, the earth goddess, when "a ball of fine feathers" fell on her. Her pregnancy was seen as shameful by her children, Coyolxauhqui and the four hundred (i.e., countless) gods of the south, and they resolved to kill her. Huitzilopochtli, still in her womb, vowed to protect his mother. As the four hundred, led by Coyolxauhqui, approached, Huitzilopochtli, born at that moment, struck her with his fire serpent and cut off her head. Her body "went rolling down the hill, it fell to pieces," and her destruction was followed by Huitzilopochtli's routing her four hundred followers and arraying himself in their ornaments.[24] As numerous commentators from Eduard Seler and Walter Krickeberg on have said, this myth clearly depicts the daily birth of the sun and the consequent "destruction" of the moon and stars as the sun replaces them in the sky. The dismemberment of Coyolxauhqui also suggests the moon's various phases as it waxes and wanes as well as its disappearance between cycles.

This myth also depicts the sun, with the virtues of the warrior, in opposition to the moon, this time female, which lacks them: Huitzilopochtli defends his mother, Coyolxauhqui betrays her; he stands alone bravely, she acts only with many followers. But here the implications go much deeper. Significantly, the moon is here depicted as female, and much of the myth's meaning turns on that opposition between male and female. For example, the myth portrays Huitzilopochtli's vowing to defend his mother as taking place while he is still in her womb, making clear that his birth from the female immediately precedes his destruction of his female sibling, an act in structural opposition to his birth: a female gives him birth; he takes a female life. But the Aztecs knew that with the coming of night he too would be destroyed, metaphorically, by being swallowed by the female earth. This further reversal (he destroys a female and is then destroyed by one) suggests the nature of the cycle in which the sun and the moon exist and also suggests the nature of cosmic reality, which both creates and destroys life, a cyclic reality also connected with the sun in the creation myth of the Five Suns.

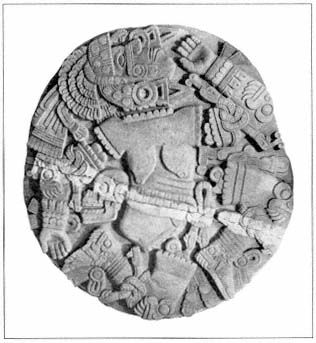

The recent discovery of the monumental Coyolxauhqui stone (pl. 59) at the base of the pyramid of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán confirms this thesis and suggests several other implications as well. The stone depicting the dismembered goddess was uncovered at the foot of the stairway leading up to the Temple of Huitzilopochtli atop the pyramid, a placement recalling the myth in which her body rolls down the hill and falls to pieces. When the sun is at its midday height, suggested by the temple at the top of the pyramid, the moon will be in the depths of the underworld, the land of the dead. But the Aztecs knew that just as the coming of the night would reverse those positions and states, so their own individual vitality, their nation's preeminent position in the Valley of Mexico, and the world age—the Fifth Sun—in which they lived would all eventually perish in the cyclic flux of the cosmos, only to be reborn, though perhaps in a different form. Thus, the killing of Coyolxauhqui paradoxically guarantees the rebirth of Huitzilopochtli and the continuation of the cosmic cycle of life, just as the sacrifice of captured warriors on the stone found by archaeologists still in place in the Temple of Huitzilopochtli and the rolling of their dead bodies down the pyramid to the stone of Coyolxauhqui at the base was seen by the Aztecs as vital to the continuation of their life and the life of the sun.

It is interesting that Huitzilopochtli's temple shared the top of the pyramid with the Temple of Tlaloc. Tlaloc, the god of rain, and the female Coyolxauhqui both have an association with fertility that opposes them to Huitzilopochtli, who is, after all, a male war god. But the myth suggests again the alternation that characterizes the daily cycle of the sun and the moon. Although associated in one sense with fertility, both Tlaloc and Coyolxauhqui also have a destructive aspect. Co-

Pl. 59.

Coyolxauhqui, Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlán

(Museo del Templo Mayor, México).

yolxauhqui's role in the myth is destructive, not creative, and Tlaloc's rain could fall in the destructive torrents of a tropical storm. In both of these cases, Huitzilopochtli can be seen again in an opposing, but this time creative, role—that of the defender of his mother and as the life-giving sun. On a profound level, then, the myth of the destruction of the moon by the sun is clearly meant to delineate the cyclic alternation between life and death, creation and destruction which seemed to the Mesoamerican mind to characterize the rhythmic movement of the cosmic cycles for which the sun provided a metaphor. The two opposed forces become one within the cycle just as the feathered headdress of Coyolxauhqui on the monumental relief at the Templo Mayor (pl. 59) suggests her ultimate union with Huitzilopochtli, her brother, "the divine eagle of the sky." The feathers are "signs of the union consummated through sacrifice" and illuminate "the manifest duality that reveals the essential unity of the god and the victim,"[25] of the sun and the moon, of life and death—the unity originally perceived by the shamanic forebears of Mesoamerica and the same unity celebrated by the metaphoric use of the ritual mask to symbolize the union of matter and spirit.

Both of these myths depict the moon as subordinate to the sun, and in both myths, the underlying meaning reinforces that subordination. For the Aztecs, the moon was not important in itself but only as its opposition could be seen to clarify the sun's role and symbolic meaning. The situation among the Maya was much the same. In the Popol Vuh, at the end of the underworld adventures of the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque, "the two boys ascended ... straight on into the sky, and the sun belongs to one and the moon to the other,"[26] a parallel to the Aztec myth of Nanahuatzin and Tecciztécatl at least in the fact that two male gods are transformed. But as in the Valley of Mexico, myths also exist among the Maya which depict the moon as female in relation to a male sun. According to Thompson, they are the norm and for contemporary Maya groups, at least, usually depict the sun and often a brother, Venus, hunting to provide food for the family. But the old woman at home, often their grandmother but always the moon, "gives all the meat they bring home to her lover. The children learn this, slay her lover, and trick the old woman into eating part of his body. She tries to kill the children, but they triumph . . . and kill her."[27] This generalized version has interesting structural similarities with the Huitzilopochtli Coyolxauhqui myth, which, with its wide distribution with many variants among the contemporary Maya, indicate its pre-Columbian origin. Both myths depict the sun as a male child in the position of supporting the ideal of sexual virtue, both depict the moon as female and as betraying a parent or child, and both, of course, depict the destruction of the moon by the sun. The emphasis on sexuality in the Maya myth parallels the emphasis on birth in the Aztec version; both focus on generation and death, and, by implication, regeneration. Thus, it is fair to say that both call attention to the basic cyclic alternation between opposed states in the cosmos and to the unity underlying and governing the cycle.

The emphasis on the regularity of the solar and lunar cycles in the understanding of the cosmic unity would seem to indicate a need to deal with the phenomena of eclipses since they are clearly disruptions of those all-important cycles, and Mesoamerica did deal with them at some length. The suggestion in the Maya myth that the moon eats part of the body of her lover (alter ego of the sun?) is interesting in this context. A passage from the Chilam Balam of Chumayel describing the disastrous events of Katun 8 Ahau reads: "Then the face of the sun was eaten; then the face of the sun was darkened; then its face was extinguished,"[28] which is echoed by the Chorti Maya belief that an eclipse is caused by the god Ah Ciliz becoming angry and eating the sun.[29] Though these are post-Conquest beliefs, they reflect the pre-Columbian fascination with and fear of eclipses. Throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, it was believed that both solar and lunar eclipses were disastrous portents signaling destruction, possibly even the end of the world, that is, the present world age or "Sun," just as the setting of the sun ended the day and the disappearance of the moon "destroyed" the night. The Maya Dresden Codex contains tables used to predict the dates of possible eclipses, tables that reflect the

working out by the Maya of the complex cycles that governed them. Given the cosmic importance Mesoamerica attributed to the cycles of the sun and, to a lesser extent, the moon, any interruption of them would seem to shake the very foundation of the universe. Interestingly, the Maya attempted to secure that foundation by finding a regularity in the occurrence of these seemingly unpredictable events, thereby including them within the cyclic nature of reality. Everything, they must have believed, when properly understood manifested the order derived from the spiritual unity underlying all reality.

The only other celestial body with which the peoples of Mesoamerica were greatly concerned was Venus. It is "the only one of the planets for which we can be absolutely sure the Maya made calculations"[30] and probably the only one that played a major role in central Mexican mythology. The reason for this, according to Aveni, is that "besides Mercury it is the only bright planet that appears closely attached to and obviously influenced physically by the sun."[31] This apparent "attachment" derives from the fact that its solar orbit lies between the earth's orbit and the sun. From the vantage point of the earth, Venus's movement can be divided into four distinct periods: (1) the period of inferior conjunction—an 8-day period when Venus is directly between the sun and the earth and thus invisible because of the sun's glare; (2) the period in which it is the morning star—a 263-day period during which the planet is most brilliant and rises before the sun in the eastern sky, at first only a moment before the sun, the annual moment of heliacal rising after inferior conjunction of utmost importance to Maya astronomers, and then for longer periods each day, the last and longest being about three hours; (3) the period of superior conjunction—a 50-day period during which the sun is between Venus and the earth; (4) the period in which it is the evening star—a 263-day period in which it is visible for a short time in the western sky after sunset, each day for a shorter period of time until inferior conjunction occurs and the cycle begins again. "The long-term motion of Venus can thus be described as an oscillation about the sun, the planet never straying far from its dazzling celestial superior."[32]

Not only was Venus tied visually to the sun but there were numerical relationships as well which fascinated the Mesoamericans. It was known throughout Mesoamerica that the synodic period described above took "584 days, the nearest whole number to its actual average value, 583.92 days and that 5 × 584 = 8 × 365 so that 5 synodic periods of Venus exactly correspond to 8 solar years."[33] In addition, there were further numerical correspondences, which are discussed below in connection with the 260-day calendar. Suffice it to say that the apparently eccentric motion of Venus actually meshed with the all-important solar cycles in a number of ways, suggesting again the basic order underlying the apparent randomness of the cosmos.

Among the Maya, "the main function of the study of Venus seems to have been to be able to predict the time of the feared heliacal rising after inferior conjunction," which could cause sickness, death, and destruction.[34] These dire predictions parallel those seen in the Codex Borgia of the Valley of Mexico,[35] and it seems likely that the Maya got these ideas from central Mexico[36] where the period of inferior conjunction was associated with Quetzalcóatl. Both mythologically and historically, in different contexts, his disappearance and reappearance under changed circumstances is central to his story. According to the Anales de Quauhtitlán ,

at the time when the planet was visible in the sky (as evening star) Quetzalcóatl died. And when Quetzalcóatl was dead he was not seen for four days; they say that then he dwelt in the underworld, and for four more days he was bone (that is, he was emaciated, he was weak); not until eight days had passed did the great star appear; that is, as the morning star. They said that then Quetzalcóatl ascended the throne as god .[37]

Quetzalcoatl's rebirth in shamanic fashion—from the bone as seed—thus accords with the sacred heliacal rising of Venus after inferior conjunction, when its rising first heralds the rising of the sun in the east (the direction of regeneration) and his death with the disappearance of the western, evening star, itself a symbol of the death of the sun. Quetzalcóatl's very name, translated as "Precious Twin" as well as "Feathered Serpent," suggests this connection with the two aspects of Venus. According to Seler, the Codex Borgia includes "myths concerning the wanderings of the divinity [of the morning star] through the underworld kingdoms of night and darkness" during the period of inferior conjunction which are similar to the wanderings of the Hero Twins in the Popol Vuh ,[38] wanderings that Coe sees as "an astral myth concerning the Morning and Evening Stars."[39] Thus, it is the period of inferior conjunction, when Venus seems to merge with the sun, and the following heliacal rising, when its rebirth heralds the rebirth of the sun, that fascinated Mesoamericans, a fascination clearly due to the interplay of Venus and the sun.

Surely, then, it is clear that when the seers of Mesoamerica looked to the heavens they saw a cosmic order revealed in the myriad, intricate cycles that meshed with the regular movement of the sun. This order became the basis of myths and rituals, the calendar that organized the ritual year, and the principle from which was derived the orientation of the great ceremonial centers in which those rituals took place. Everywhere one turns, one finds evidence in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica of the at-

tempt to replicate the order of the sun's cycles in man's earthly world and through that replication to understand the workings of the inner life of the cosmos, an understanding fundamental to Mesoamerican cosmology and cosmogony and an understanding for which the mask stood as metaphor.

Generation, Death, and Regeneration

The regular cycles of the sun not only revealed the cosmic order but suggested, just as surely, an orderliness in man's life and in the world he inhabited: implicit in the regularity of the solar cycle was the entire mystery of death and rebirth, the cycle of regeneration as it was manifested in the natural world. As Eliade puts it, "generation, death, and regeneration were understood as the three moments of one and the same mystery, and the entire spiritual effort of archaic man went to show that there must be no caesuras between these moments. . . . The movement, the regeneration continues perpetually."[40] And as Mesoamerican man looked at his world, the mystery of renewal was everywhere before him: the cycle of the sun as it moved from its zenith to the horizon and disappeared into the chaos of the night always to return from that chaos to be reborn; the changes in the moon as it gradually moved from its creation as the new moon to its growth as a full moon, diminishing to a final "death" before its reappearance once again as the new creation; the changes in the season from the periods of fullness to those of disintegration before a renewal of the cycle; the various stages in the process of the growth of his plants from the "dead seed" to the fully mature fruits; and even such a small thing as the life cycles of the snake and the butterfly with moments of "rebirth" punctuating the stages of development. Life could be counted on not to end; it was always in the process of transformation. And every stage of that process, including a symbolic, if not real, return to the "precosmogonic" chaos[41] through night and the dry season and even death, was an essential aspect of the mystery.

Through this process of regeneration manifested in the annual renewal of plant life, the gods provided sustenance for humanity, and ritual reciprocation was required. "Each stage of the farming round was a religious celebration[42] of the divinely ordained mystery of "generation, death, and regeneration" in the sowing, nurturing, and reaping of the agricultural cycle. Thus, throughout Mesoamerica, ritual imitated nature and reflected the seasonal changes by "depicting the life cycle of domestic plants as well as their mythic prototype, the primordial course of events on the divine plane."[43] The rituals marked not only the transition from seed to maturity but, in their calendrical regularity, the very movement of time itself. Durán was aware of this ritual purpose as he lamented the destruction of the records that told of the calendar that

taught the Indian nations the days on which they were to sow, reap, till the land, cultivate corn, weed, harvest, store, shell the ears of corn, sow beans and flaxseed. . . . I suspect that regarding these things the natives still follow the ancient laws and that they await the correct time according to the calendrical symbols.[ 44]

Corn, mankind's proper sustenance, was the focal point of this ritual cycle and was regarded as divine throughout Mesoamerica. Thompson points out that "in Mexican allegorical writing jade is the ear of corn before it ripens, and like the green corn, it is hidden within the rocks from which it is born and becomes divine. . . . The maize god always has long hair, perhaps derived from the beard of the maize in its husk."[45] Even today among the Lacandones, Bruce reports that the basic cycle of time is not related as much to the sun or to human life as it is to

the corn, so inseparably linked with the life of the Mayas. The dry, apparently dead grains are buried in the spring. . . . The plants grow from tender, green youth to maturity and are then called to descend to their destiny in the shadows. The plants wither, they are "decapitated" or harvested, shelled, cooked, ground and eaten—though a few grains are saved. Fire (Venus, the Morning Star) clears the earth into which the seeds are cast and buried. Then the cycle begins anew.[46]

Applied metaphorically to man's life, the cyclical pattern of the corn promises the immortality of regeneration, a promise especially clear to the agricultural communities of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica as "the milpa cycle runs many times during the lifetime of a man, which has the same characteristics." The cycle of the corn teaches the same lesson as the cycle of the sun: all that is to come has already been; "more correctly, 'it simply is"'[47] in the vast cyclic drama of the cosmos.

The Aztec god Xipe Tótec, although clearly a complex and multivocal symbolic entity, embodies this concept; representing spring, the time of renewal, he is shown wearing the skin of a sacrificial victim as a garment (pl. 47). In the ritual dedicated to him and enacted at the time of the planting of the corn, a priest donned the skin of a victim, representing in this sense the dead covering of the earth in the dry season of winter before the new vegetation bursts forth in spring. As with the more usual ritual mask wearer, that priest represented the life-force existing eternally at the spiritual core of the cosmos and in his ritual emergence from the dead skin demonstrated graphically life's emergence from death in the cyclic round of cosmic

time. Thus, Xipe Tótec was the divine embodiment of life emerging from the dead land, of the new plant sprouting from the "dead" seed. It followed that "the land of the dead is the place where we all lose our outer skin or covering," a fundamental concept "contained in the phrase Ximoan, Ximoayan, which describes the process of removing the bark from trees and is thus closely related to the idea of the god who flays the dead man of his skin."[48] In the cyclical pattern, death is always a beginning, a rite of passage, a transition to a spiritual mode of being,[49] and an essential stage preceding regeneration in the transformational process. Thus, the development of the life-force within each human being paralleled the sacred movement of time. The rhythms of life on earth as manifested in the succession of the seasons, the annual cycles of plant regeneration, and the individual life that encompassed birth, growth, procreation, and death were intimately parallel to those of the heavens,[50] a parallelism that gave a divine aura to the human processes.

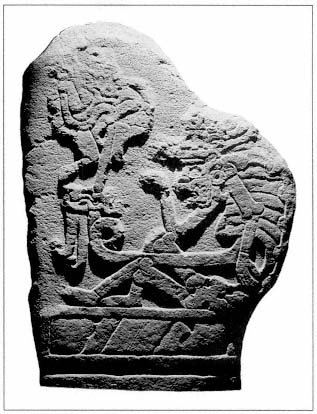

These fundamental ideas grew from the shamanic base of Mesoamerican religion with its emphasis on transformation, and that shamanic world view included the idea that "the essential life force characteristically resides in the bones. . . . [Consequently] humans and animals are reborn from their bones,"[51] which, like seeds, are the very source of life. Thus, Jill Furst contends that in the Mixtec Codex Vindobonensis, "some, if not all, skeletal figures . . .were deities with generative and life-sustaining functions," and her reading of the codex shows that skeletonization "symbolizes not death, but life-giving and life sustaining qualities." [52] This, of course, is the same metaphoric message carried by Xipe Tótec: death is properly seen as the precursor, or perhaps even the cause, of life. The striking visual image on Izapa Stela 50 (pl. 60) depicting what appears to be a small human figure attached to an umbilical cord emerging from the abdomen of a seated, masked skeletal figure puts this idea in its clearest symbolic form. There are, of course, many other manifestations of the belief that life is born from death. There is a scene in the Codex Borgia, for example, showing the copulation of the god and goddess of death, a depiction of "death in the act of giving life, . . . perfectly natural for a world that sees death as only another form of life."[53] And Francis Robicsek and Donald Hales identify many "resurrection events" on Maya funeral vessels; one shows "a young male rising from a skull, an event that can only mean emergence from death to life."[54] Still another connection between bones and rebirth can be seen in Ruz's suggestion that throughout the Maya lowlands, from the earliest times red pigment was used to cover bones and offerings because red, which "was associated with east where the sun is reborn every morning, may also have been a symbol of resurrec-

Pl. 60.

Stela 50, Izapa (Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

tion for men."[55] Ancestor worship shows yet another aspect of the concept. Among the Maya, as we have seen, dead members of the elite, especially rulers, "from whose race they sprang in the first place" were apotheosized as divinities.[56] And this belief was shared by those in central Mexico, as can be seen in a passage from the Codex Matritensis:

For this reason the ancient ones said

he who has died, he becomes a god.

They said: "He became a god there,"

which means that he died.[57]

The life-force never dies; it moves in a cycle from ancestors to descendants, joining them in a spiritual pattern essentially the same as the one traced by the sun as it moves from its zenith to the underworld below and rises again as well as the one manifested in the "dead" seed sprouting new life.

These beliefs account for several of the burial practices found in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The fact that tombs were placed under and near temples, as at Monte Albán and throughout Maya Mesoamerica, suggests that when the hereditary elite died, they moved from earthly to spiritual leadership. Since "the ancestral dead were considered to be assimilated to the cosmos,"[58] they could function as intermediaries with the divine and thus maintain a connection with their living descendants.[59] So sure were the Maya that the dead person continued to live in altered form that not only food but "objects which belonged to him and which

characterized his office or rank and, sometimes, his sex and age" were buried with him. The jade bead characteristically found in the mouth of the deceased in Maya burials as well as those of the Zapotecs and Mixtecs "confirms the writings of the chroniclers of the Spanish Conquest when they refer to the belief of the Mayas and the Mexicans that jade was the currency to obtain foodstuffs and to facilitate one's entrance into the next world."[60] The tomb itself often "replicated the palace, so that the ruler could continue to enjoy those prerogatives which were his in life."[61] Others were buried in natural caves because, as we have seen, the cave was metaphorically the womb of the earth, the place of rebirth.[62] And the assumption that death precedes life is also to be found at the heart of the mythological tradition of Mesoamerica. The narratives of the Hero Twins of the Popol Vuh and those detailing the activities of Quetzalcóatl as the evening star place the return from death at the symbolic center of their tales. Clearly, the number of ways in which the belief in regeneration was expressed throughout Mesoamerica from the earliest times, ways to which we have only briefly alluded here, suggests the fundamental nature of that belief.

The Temple of Inscriptions at the Maya site of Palenque contains a stunning expression of the parallels we have been discussing as it brings together a number of sun-related cycles referring to regeneration on a number of metaphoric levelsthe growth of corn, the transfiguration of ancestors, the movement of power from the dead ancestor to the living ruler, all of them affirmations of the belief that life will come from death. At Palenque, we can see the political implications of this world view: many of the monuments containing images related to cyclical regeneration are dedicated to the dynasty of which Pacal, ruler of Palenque from A.D. 615 to 683, was a member. The relief on the lid of the sarcophagus (pl. 10) in which he was buried in the tomb within the Temple of Inscriptions, for example, contains several images identifying him with the symbol of the setting sun, the Quadripartite Monster, with whom he is "metaphorically equivalent" at the time of his death. This equivalency inevitably suggests his rebirth with the rising sun as does the jade effigy of the sun god placed in his tomb.[63] Just above this scene is a youth in a reclining position whose body lies "upon various objects, two of which are symbols associated with death (the sea shell and a sign that looks like a percentage symbol), while the other two, on the contrary, suggest germination and life (a grain of corn and a flower or perhaps an ear of corn)."[64]

Thus, the earth not only takes life but generates it as well. According to Kubler, the corn symbolism is "metaphor or allegory for renewal in death, whereby the grown corn and the dead ruler are equated as temporal expressions promising spiritual continuity despite the death of the body," and he notes that Thompson also sees a metaphor of resurrection but sees the scene as "ritualistic," perhaps having "no reference to the buried chief."[65] And although Coe, Robertson, and Schele and Miller all see this plant as a world tree rather than corn, they too agree that the theme of the relief is resurrection.[66] Robertson, for example, sees the plant as the sacred ceiba tree reaching from a cave in the underworld through the middle world of the earth's surface to the heavens, a graphic image of transcendence,[67] while Ruz takes a more philosophical view of resurrection:

The youth resting on the head of the earth monster must at the same time be man fated to return one day to earth and the corn whose grain must be buried in order to germinate. The cruciform motif upon which the man fixes his gaze so fervently is the young corn which with the help of man and the elements rises out of the earth to serve once more as food for humanity. To the Maya, the idea of resurrection of corn would be associated with the resurrection of man himself and the frame of astronomical signs around the scene symbolizing the eternal skies would give cosmic significance to the perpetual cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth of beings on the earth.[68]

He is convinced that the figure is not that of the buried ruler (he maintains that the Maya would have thought more symbolically) but probably represents either humanity or the corn, often symbolized by a young man.[69] Westheim adds the dimension of the sacrifice, noting that the seed must die so that the plant may sprout, thereby indicating that "constant renewal of the cosmos was possible only through human sacrifice, just as the continued existence of the human race was ensured only through the constant rebirth of the maize."[70] Although these major commentators on pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilization offer different interpretations of the scene, the common denominator is the theme of the rising, falling, and regenerative pattern of the sun, here particularly applied to the regeneration of political power. Thus, even in the affairs of state, the principle of regeneration, intimately related to the cyclical movement of the sun through the heavens, is operative.

And other manifestations of the symbolism of regeneration can be seen in the tomb at Palenque. Both Franz Termer and Ruz have noted the unusual shape of the cavity that held the body, describing it "as a stylized representation of the womb. Burial in such a cavity would be a return to the mother by association of the concepts of mother and earth, sources of life."[71] The belief that the dead and the living communicate with each other is graphically represented by the hollow plas-

ter tube replicating the umbilical cord, which, in the form of a serpent, itself a symbol of regeneration, goes from the sarcophagus, following the stairway, up to the floor of the temple and thus provides a physical symbol of the spiritual link between the two realms. The red paint with which the crypt was covered, as we have seen, is a color associated with the east, the region from which the reborn sun appears after its return from the land of the dead, and here, as elsewhere among the Maya, is a symbol of regeneration and "an augury of immortality."[72] But perhaps the most fascinating suggestion of regeneration can be seen in the way the Maya

manipulated architecture so that the movement of the universe confirmed the assertions of mythology. Just as the sun begins its movement northward following the winter solstice, the dead, after the defeat of death, will rise from Xibalbá to take up residence in the northern sky, around the fixed point of the North Star. Pacal, confident of defeating death, has made north his destination: His head was placed in the north end of the coffin, and the World Tree on the lid points north, although Pacal himself is depicted in his southward fall. Just as the sun returns from the underworld at dawn, and as it begins its northward journey after the solstice, Pacal has prefigured his return from the southbound journey to Xibalbá.[73]

John Henderson points out that those observing the actual movement of the sun at Palenque would have visual proof of the phenomenon.

The sun itself appeared to confirm these symbolic associations. As the sun sets on the day of the winter solstice, when it is lowest and weakest, its last light shines through a notch in the ridge behind the Temple of Inscriptions, spotlighting the succession scenes in the Temple of the Cross. . . . Observers in the Palace saw the sun, sinking below the Temple of Inscriptions, follow an oblique path along the line of the stair to Pacal's tomb. Symbolically, the dying sun confirmed the succession of Chan Bahlum, then entered the underworld through Pacal's tomb. No more dramatic statement of the supernatural foundation of the authority of Palenque's ruling line is imaginable .[74]

Thus, both art and nature confirmed without question the Maya belief that life must follow death. The message was clear: "A king dies, but a god is born."[75] And as our discussion of the mask placed over the once-living face of Pacal as he was put in that sarcophagus made clear, the features of the dead man, through the metaphoric agency of the mask, became the eternal features of the deified ancestor. His inner reality had become "outer" in the most significant and final way.

The expression of the theme of resurrection in visual images is not limited to the Maya. One of the most important monumental sculptures of central Mexico, the Aztec Coatlicue (pl. 9), "says" the same thing. Although these two masterpieces were created centuries apart by different cultures, all of the imagery associated with Palenque's Temple of Inscriptions seems to be telescoped symbolically into this Aztec representation of the earth goddess which, according to Fernández,

symbolizes the earth, but also the sun, moon, spring, rain, light, life, death, the necessity of human sacrifice, humanity, the gods, the heavens, and the supreme creator: the dual principle. Further it represents the stars, Venus and... Mictlantecutli, the Lord of the Night and the World of the Dead. His is the realm to which the sun retires to die in the evening and wage its battle with the stars to rise again the following day. Coatlicue, then, is a complete view of the cosmos carved in stone. . . . It makes one conscious of the mystery of life and death. [76]

The sculpture is a visual myth clearly related to the ritual involving the great mother goddess, a ritual in which a woman impersonating her was sacrificed to reenact her death, the propitiation of the earth, and her rebirth. This festival took place near the time of the harvest when the earth itself, having been renewed through death, would again provide the nourishment for life. Both Coatlicue and the earth granted everything with generous hands but demanded it back in repayment; and like the sun, they were both creator and destroyer. All of this is magnificently symbolized by the colossal sculpture of Coatlicue now in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City: she wears a skirt of braided serpents and a necklace of alternating human hands and hearts with a human skull pendant. She is decapitated as were those sacrificed to her, and two streams of blood in the form of two serpents flow from her neck. Facing this figure, overpowering both in size and imagery, the observer must agree with Westheim that "there is no story; there is no action. [She stands] in majestic calm, immobile, impassive—a fact and a certainty."[77] And with Caso: "This figure does not represent a being but an idea.[78] She is a metaphoric image of the womb and the tomb of all life and simultaneously the embodiment of the cyclical pattern that unites them.

That certainty of death and regeneration, of the cyclical nature of the universe, was at the very core of the Mesoamerican world view. What Bruce says of the Maya is equally true of the other peoples of Mesoamerica: "The solar cycle pervades all Maya thought and cosmology. . . . It is the basic nature, not only of 'time,' but of Reality itself."[79] And that basic cycle provided Mesoamerica with a framework for thought; all the elemental processes of life

were cast in that mold—the stages in the growth of the corn from seed to harvest, the stages in the development of human life, the necessity of sacrifice to guarantee the continuation of life, and the ultimate unity of life and death manifested politically at Palenque, verbally in the experiences of the Hero Twins in the Popol Vuh and the tales of Quetzalcóatl, and visually in the sculptures of Coatlicue and Pacal's tomb.

But the awareness of this underlying unity did not negate the awe with which Mesoamerican man viewed the mystery of death. That mystery suggested the sacred nature of the cycle which transcended earthly matters and made man aware of his contingent nature. Joseph Campbell uses the metaphor of the mask to place the words of an Aztec poet in context: "Life is but a mask worn on the face of death. And is death, then, but another mask? 'How many can say,' asks the Aztec poet, 'that there is, or is not, a truth beyond?'

We merely dream, we only rise from a dream

It is all as a dream."[80]

Another poem from the same body of late Aztec poetry, however, using the metaphoric identification of flower and song with poetry itself, was able to lift the mask and find beneath it the assurance of "a truth beyond."

O friends, let us rejoice,

let us embrace one another.

We walk the flowering earth.

Nothing can bring an end here

to flowers and songs,

they are perpetuated in the house

of the Giver of Life.[81]