Chapter 14

Washington Intervenes Draper and Kennan

U.S. economic planning for postwar Japan was a multifarious collection of generally worded reforms, punitive measures, and a firm disclaimer of any obligation to help the Japanese feed themselves and rebuild their country. These policies were carried out by a commander and senior staff with little experience in economic matters. It was characteristic of MacArthur, as his entire career showed, that he did not shrink from responsibility and did not feel entirely tied down by Washington orders. Soon after the occupation began, he was asking for food and raw materials to enable Japan to escape starvation and stagnation. Washington went along. In the first year after the surrender the United States provided Japan with a little more than $100 million in food, fertilizer, petroleum products, and medical supplies, financed by military appropriations.[1]

By 1947 Washington wanted more action by SCAP and better performance by Japan. In a speech on May 8, 1947, Dean Acheson proposed that Germany and Japan be converted into the "workshops" of Europe and Asia, foreshadowing Secretary of State Marshall's momentous speech at Harvard only a few weeks later launching the European recovery program.[2] On August 30, 1947, the newly reorganized Defense Department in Washington filled the new position of under secretary of the Army by appointing General Draper, a dynamic man with broad business and military experience. Washington wanted to build up SCAP's economic staff as well but could not figure out how to overcome MacArthur's well-known resistance to having top posts on his staff

filled by people he did not know and trust.[3] He was particularly averse to Wall Street bankers. As it happened, Draper and the new secretary of defense, James V. Forrestal, were both senior members of the New York investment firm of Dillon, Read.

One of Draper's main tasks was to supervise Defense Department management of areas occupied by U.S. forces after World War II, in particular Germany and Japan. He had served for two years on the staff of General Lucius D. Clay, the military governor of the U.S. zone in Germany, but he knew little about Japan. So Draper decided to go there in September 1947. He met with General MacArthur, his staff, and a number of Japanese including Prime Minister Katayama. Draper was impressed that "the Japanese are cooperating to an unbelievable extent with the occupation," but he got a negative picture of the economic situation. He was disturbed, as he had been in Germany, by the huge costs of the occupation and by the campaigns to break up large business concentrations.[4]

His visit to Japan came at a time when the SCAP anticartel program was going strong. The man in charge, Edward C. Welsh, was a trained economist hired to expedite the program. Welsh arrived in Tokyo in March 1947 and became one of SCAP's most zealous operators, immediately seeing that he would lose influence to GS if he did not move fast on the cartel issue. One of his first actions was to push for dissolution of the two huge trading companies, Mitsubishi Shoji and Mitsui Bussan, which had handled much of Japan's prewar export and import business. Bussan was split into 170 companies and Shoji into 120. No persuasive reason was ever advanced for the breakup of these companies, except, of course, that they were the trading agents for the far-flung enterprises of these two conglomerates. It seemed irrational to destroy them at a time when SCAP had allowed foreign traders to enter Japan and was trying to revive Japan's trade despite the resistance of many of the Allied nations. (The two companies were recombined soon after the end of the occupation. By 1985 they were the second and third largest non-U.S. companies in the world.)[5]

Draper readily perceived that staff officers directed economic operations in Tokyo and that MacArthur and his economic chief, Marquat, provided little input. Draper was not an archconservative or a Wall Streeter looking for capitalist opportunities, but he was an investment banker who carefully studied balance sheets and speedily detected financial trouble. He clearly saw that Japan's productive potential was hobbled by SCAP restrictions and red tape as well as by high inflation.

By the time he returned to Washington, Draper had formulated a broad plan of action. He wanted a policy statement stressing the importance of economic recovery as a U.S. objective. Getting such a statement was easy, despite objections in the State Department that existing policy was adequate. On January 22, 1948, the new State-Army-Navy-Air Coordinating Committee (SANACC, renamed to include the new U.S. Air Force) approved a weasel-worded statement that the supreme commander "should take all possible and necessary steps consistent with the basic policies of the occupation to bring about the early revival of the Japanese economy on a peaceful, self-supporting basis." Secretary of the Army Royall heralded the new American approach in a speech on January 6, 1948: "There has arisen an inevitable area of conflict between the original concept of broad demilitarization and the new purpose of building a self-supporting nation." He clearly implied that the latter purpose had become number one for the United States.[6] Royall's speech was one of the first signs of a new direction in U.S. policy.

The next step was a specific plan. In 1947 Washington and Tokyo were working on plans that turned out to be similar. Draper carried to Tokyo a State Department plan called Crank Up that aimed at a self-supporting Japan by 1950. SCAP's "green book" planned that the United States would provide $1.2 billion in assistance, Japan would become self-supporting in four years, and by 1953 it would be able to export $1.5 billion worth of goods and services. By 1947 U.S. aid was running at about $400 million a year and was even higher for the next two years. All these plans became outmoded when the Korean War broke out in 1950.[7]

To implement his economic strategy Draper targeted two occupation programs for reduction or elimination—reparations and deconcentration of big business—even though the State Department remained opposed to any changes. Reparations, however, were a crucial issue in the FEC, where "more time was given ... to Japanese reparations and related topics than to any other subject which came before the commission."[8] Draper was more impressed, however, by the potent argument that the American taxpayer would eventually pay for any reparations deliveries because whatever Japan shipped out as reparations would delay its recovery and lengthen its period of dependence on the United States for assistance.

One of Draper's clever devices was to commission a group of influential businessmen to study a problem, make sure they knew his view-

point and were generally sympathetic, and then use their report to justify a shift in policy. This was the way he worked out the reparations matter. First came the Overseas Consultants, Inc., under engineer Clifford Strike, which made two surveys in 1947 and recommended huge reductions in the industrial facilities listed by the Pauley report of 1946. Asked for his views on the Strike report, MacArthur asserted on March 21, 1948, that the "decision should be made now to abandon entirely the thought of further reparations.... In war booty Japan has already paid over fifty billion dollars by virtue of her lost properties in Manchuria, Korea, North China and the outer islands.... Except for actual war facilities, there is a critical need in Japan for every tool, every factory, and practically every industrial installation which she now has."[9]

As his second step in the attack on reparations, Draper organized and participated in another study two months later by a group led by Percy Johnston, the chairman of the Chemical Bank and Trust Company of New York. After a three-week stay in Japan, the Johnston committee recommended far larger reductions than those of the Strike committee. Strike had recommended a 33 percent cut in the Pauley proposals, and Johnston recommended a cut of more than 50 percent in the Strike plan. Altogether, reparations would be 25 percent of the 1945 plan.[10] The new approach was the kind that Draper and MacArthur wanted. The State Department questioned the extent of damage that would be done to Japan's economy by the earlier reparations proposals and argued that the SCAP-Army position would be unacceptable to the FEC nations.

On July 25, 1948, MacArthur cabled Washington that Japan would need to retain much of its industrial capacity: "Indications are now that Japanese export trade of the future will have a substantially different pattern than prewar. With the rapid expansion of the cotton textile industry in other countries in the Far East ... it is indicated that future Japanese exports will consist much more of machinery, other capital goods and chemicals, and much less proportionately of textile products than prewar. This ... will require a larger steel and machinery capacity to support export industries with no change involved in the internal domestic standard of living."[11]

The coup de grace to the Allied reparations program came in 1949. On May 6 the United States decided, in NSC-13/3, that the advance transfer program should be terminated and that the FEC should be, advised that all industrial facilities, including ."primary war facilities" stripped of their military characteristics, should be used as necessary for the recovery program. Many factories used for war production in

World War II were later sold to private companies for peaceful production; industrial equipment designed solely for. military purposes was later destroyed by SCAP pursuant to a FEC policy decision of October 30, 1947. On May 12, 1949, the United States rescinded the advance reparations transfer directive to MacArthur and so informed the FEC.[12]

The U.S. action fueled resentment in several Asian countries, notably the Philippines and the ROC, that American policy favored Japan at their expense. This claim had much to justify it, though the American rejoinder that transplanted factories and equipment were rarely usable in backward countries was about equally true. Several points are significant: if the Allies had reached quick agreement on reparations and early deliveries had been carried out by Japanese technicians under Allied supervision, the program might have been beneficial to Asian nations. In fact, however, the Allies probably took too little from Japan after World War II and took too much from Germany after-World War I.

Some critics of American policy claim that reparations were another example of a U.S. policy reversal. It did indeed reverse its position because the U.S. government decided, not without reason, that if Allied agreement could not be achieved in three and one-half years, the policy should be given up. This made all the more sense because reparations were not a reform but a punitive policy that held out little promise of assistance to the Allies.

Draper's campaign to wind up the deconcentration program proceeded more easily and quickly than the struggle over reparations. The main battle, breaking up the zaibatsu holding companies, had long since been completed, but the program to dissolve a large number of big business groupings was just getting started. MacArthur, however, began to have some doubts. Reportedly, he thought it "sounded crazy" to designate 325 companies as excessive concentrations two and one-half years after the antizaibatsu campaign began. Accordingly, he suggested to Washington in January 1948 that an impartial board of American businessmen come to Tokyo to review the deconcentration program. Draper soon put together a group of five men in whom he had confidence. The Deconcentration Review Board arrived in Japan in May 1948. By then some 150 companies had been removed from the original list of 325. The board steadily pared the list during the year of its operation, though it was careful to save SCAP face when it announced in September "there has been no change whatsoever" in SCAP deconcentration policy.[13]

While the board was swinging into action, Draper busied himself

with redirecting deconcentration policy. The first step was to end consideration of FEC-230. After another protracted battle between State and Army, the U.S. representative to the FEC was authorized to state on December 9, 1948: "There is no need to lay down policies for the guidance of the Supreme Commander with respect to any remaining significant aspect of the program Hence, the United States has withdrawn its support of FEC-230 The major points of procedure set out in that document already had been implemented in Japan." General McCoy noted in his statement to the FEC that "the assets of fifty-six persons who comprised the ten major zaibatsu families and the assets of the eighty-three holding companies controlled by these persons have been acquired by the government and are in process of being sold to the Japanese public."[14]

Of the original 325 companies, 297 had been exempted when the Deconcentration Review Board dissolved on August 3, 1949, orders for reorganization of 11 others had been issued, and the remaining 17 cases were in the final stage of processing. The SCAP deconcentration program actually split up only 18 companies, including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Mitsubishi Mining, Mitsui Mining, Toshiba, Hitachi, Oji Paper, and Japan Steel, which was split into Yawata Steel and Fuji Steel.[15]

Japan's biggest banks did not fall under the 1947 Law for Elimination of Excessive Concentrations of Economic Power. These banks, including Dai Ichi, Chiyoda (a cover name for Mitsubishi), Fuji (cover for Mitsui), Osaka, and Sanwa, played a key role along with a number of new banks in Japan's economic revival after the occupation. Thirty-six years after the occupation ended, the ten biggest banks in the world were Japanese.[16]

MacArthur told Patrick Shaw of Australia in April 1949 that the Draper mission was "the most high-powered effort of big business interests to break down his policy of preserving Japan from carpetbaggers." The Canadian representative, Herbert Norman, had commented earlier, "On more than one occasion I have noticed General MacArthur's addiction to the vocabulary of the trust-busting era; thus his determination to break up the zaibatsu in Japan is a genuine part of his political philosophy." A Japanese business leader said later that "zaibatsu dissolution was a major factor in Japan's postwar growth." It also helped bring about a managerial revolution in which stockholding was widely dispersed, managers ran companies, and in most industries competition was keen.[17]

Draper's campaign to make economic recovery the top priority of the occupation was the first serious intrusion by Washington into MacArthur's autonomy in Tokyo. Soon after came a statement of national policy that provided a broad framework for the new approach. Approved by President Truman on October 9, 1948, this document was one of the early products of the National Security Council (NSC) and became well known as NSC 13/2.[18]

NSC 13/2 was primarily the brainchild of George F. Kennan, who at age forty-three was regarded as America's foremost authority on policy toward the Soviet Union. His article in the July 1947 issue of Foreign Affairs on the sources of Soviet conduct had won wide acceptance as a perceptive and realistic prescription for the United States and its friends to follow in dealing with the communist nations. His analysis became an essential element in U.S. foreign policy and was universally known as containment, a description he did not entirely appreciate and the meaning of which was hotly debated.

Secretary of State Marshall appointed Kennan the head of a new policy planning staff in 1947. After completing a study on European recovery that was valuable in the formulation of the Marshall Plan, Kennan and his staff decided to look at Japan. The immediate issue they faced in the late summer of 1947 was whether to go along with plans for a peace conference, for which Far Eastern experts in the State Department had made extensive preparations. The basic point, in Kennan's view, was to determine whether Japan was stable and strong enough to stand on its own feet; he was convinced that the restoration of a postwar balance of power required that Western Europe and Japan stay out of communist hands.[19]

Kennan had had no experience in the Far East. Concerned that U.S. policy in Japan might have the effect of "rendering Japanese society vulnerable to Communist political pressures and paving the way for a Communist takeover," he suggested that someone go to Japan to talk to MacArthur and examine the situation there firsthand. Kennan sensed that relations between Marshall and MacArthur were "not cordial" and that the secretary of state was "reluctant to involve himself personally in any attempt to exchange views with General MacArthur." No one in the State Department seemed to want this job, and the task soon fell to Kennan.[20]

He was the most important State Department official to visit Japan during the occupation. In the same period high officials went regularly to Europe; Secretary of State Dean Acheson, for example, made eleven

trips between 1949 and 1952. Although State Department officials complained that their views did not get much hearing in Japan, they shrank from any direct tilt with MacArthur. MacArthur's military associates in the Pentagon had many of the same problems with the general, and Kennan thought they probably relished "watching a civilian David prepare to call on this military Goliat.".[21]

Kennan arrived in Tokyo at the end of February 1948. His detailed reports of his three meetings with MacArthur are among the rare records of MacArthur's views that can be called complete and candid. After an uncertain start, Kennan and the general got along surprisingly well. At their first meeting, a luncheon on March 1, the general held forth in a virtual monologue, a "MacArthur sermon," about the prospects for democracy and Christianity in Japan. "Overcome by weariness," Kennan says, he had little to offer at this meeting.[22]

In advance of the second meeting, Kennan sent the general a note, which reflected his own thoughts, suggesting that the emphasis of occupation policy should be threefold: the "maximum stability of Japanese society" based on a "firm U.S. security policy," an "intensive program of economic recovery," and a "relaxation in occupational control designed to stimulate a greater sense of direct responsibility" in the Japanese.[23]

At the meeting of March 5 MacArthur responded at length. Regarding security, he asserted that the strategic boundary of the United States ran along the island areas off the eastern shore of the Asiatic continent and that Okinawa was "the most advanced and vital point in this structure," which the United States had to control completely. MacArthur further noted that it would not be feasible for the United States to retain bases in Japan after a peace treaty because other Allied nations would then have a right to do likewise. Regarding economic recovery, the general agreed that it should be made a primary policy goal. He was already doing all he could to achieve this, he said, but the difficulty was in the development of foreign trade, and in this matter the FEC nations were "shamelessly selfish and negative" toward Japan.[24]

Regarding a relaxation of control, MacArthur asserted that occupation controls were not so stringent as many in the United States thought. The general went on to describe some of the reform measures. Provisions in the new constitution renouncing war had resulted from a Japanese initiative. The zaibatsu were not men of superior competence; the real brains of prewar Japan were in its armed forces. Most reform measures had been completed, civil service reform being the only im-

portant one remaining. MacArthur said he was planning to cut down the SCAP section most concerned with subjects of interest to "academic theorizers of a left-wing variety," commenting that he had a few of these in his shop but did not think they did much harm.[25]

Changing the subject, Kennan suggested that the FEC, which MacArthur had indicated would be an obstacle to any attempt to change occupation policy, had largely fulfilled its main function and could be "permitted to languish." The general thought this was the right line to take and said he could easily certify to the FEC within a short time that the surrender terms had been carried out. Kennan summarized by saying the position should be that "the occupation is continued, not for the enforcement ... of the terms of surrender, but to bridge the hiatus in the status of Japan caused by the failure of the Allies to agree on a treaty of peace."[26]

At the third meeting, on March 21, Draper took part and mentioned that some planners in the Department of the Army thought Japan should have a "small defensive force." MacArthur prefaced his reply by urging that the United States press for an early peace conference, suggesting that if a treaty could be negotiated, the Soviets would eventually go along with it. He then asserted that he was "unalterably opposed" to a Japanese military force because it would violate fundamental SCAP policies and alienate Far Eastern nations. A rearmed Japan would have trouble surviving economically and could never be more than a fifth-rate military power, "a tempting morsel, to be gobbled up by Soviet Russia at her pleasure." In addition, the Japanese had sincerely renounced war and would be unwilling to establish an armed force.[27]

While in Japan, Kennan formed strong and skeptical views on some occupation policies. Speaking of the purge program, he commented later, "The indiscriminate purging of whole categories of officials, aside from the sickening resemblance to the concepts of certain totalitarian governments, was a denial of the civil rights provisions of the new Japanese constitution and created an unfortunate setting for the promulgation of Japan's new legal codes." The anticartel program was in his eyes the work of people who saw problems "exclusively from the standpoint of economic theory and whose enthusiasm and singleness of purpose have sufficed to get them documented as U.S. government policy." He thought war crimes trials "were profoundly misconceived." The "hocus-pocus of a judicial procedure" belied the fact "they were political trials." Echoing Winston Churchill, Kennan asserted it would have been better "if we had shot these people out of hand at the time of the

surrender." As for reparations, he said, echoing MacArthur, it was "sheer nonsense ... and basically inconsistent with the requirements of Japanese recovery" to transfer industrial equipment from Japan to other Far Eastern countries. He was also somewhat appalled by the lifestyle of American occupationaires, commenting that "it is instructive rather than gratifying to get a glimpse of this vast oriental world, so far from any hope of adjustment to the requirements of an orderly and humane civilization, and to note the peculiarly cynical and grasping side of its own nature which Western civilization seems to present to these billions of oriental eyes, so curious, so observant, and so pathetically expectant."[28]

After three weeks in the Far East, including a short inspection trip to the Philippines, Kennan returned to Washington. Within a few days, his report to the NSC was ready. It began with a caveat that the United States should not press for a peace treaty. He explained later that "in no respect was Japan at that time in a position to shoulder and to bear successfully the responsibilities of independence that could be expected to flow at once from a treaty of peace." This was not, of course, the view of General MacArthur.[29]

The report offered twenty important policy prescriptions. Next to its security interests, the United States should make economic recovery its primary goal, stressing to the Japanese the need to increase production and exports. Kennan's proposals regarding political reform were more controversial: SCAP should undertake no new reforms and should relax pressures on those already in effect, intervening only if the Japanese sought to revoke or compromise fundamental reforms. The control system under SCAP should be maintained, but more responsibility should be given to the Japanese government. The report gave a lot of attention to Okinawa and went along with MacArthur: the United States should "make up its mind at this point that it intends to retain permanently the facilities at Okinawa."[30]

Kennan was most concerned about the weak power of the police, which had been broken up into many small units that lacked central direction, a central pool of information, and any means of coordination between the national rural police and the local police. Police officers were armed mostly with pistols, with only one for every four men. In Kennan's words, "It was difficult to imagine a setup more favorable and inviting from the standpoint of the prospects for a communist takeover." He cited as an example of his concern that police in Tokyo had no records of lawless elements in Osaka, such as dissident Koreans.

In his report Kennan recommended that the police be strengthened by better equipment, creation of a coast guard, and establishment of a central organization along the lines of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He did not recommend any increase in the size of the police forces, and he made no recommendations regarding a military force, but he did talk with Draper about the possibility of "a strong, centrally-directed, National Rural Police." Kennan also thought the SCAP purge categories had been too rigid and should be reviewed to permit some exceptions.[31]

On another knotty issue, a greater civilian role in the occupation, Kennan partly disagreed with MacArthur, recommending that the State Department send a permanent political representative to Japan. Even this modest compromise fell by the wayside as his report made its way upward through the U.S. government, as did an ambitious scheme by some in the State Department to assume control of all nonmilitary activities in Japan. MacArthur was adamant in his opposition. He liked being supreme. There was little talk after 1948 of any change in the structure of the occupation.

Kennan proposed other ways to bring about a more normal relation with Japan. Cultural interchange between Japan and the United States should be strongly encouraged. Precensorship of the press should cease. The impact of the large American military community in Japan should be mitigated, and the costs of the occupation paid by the Japanese government should be reduced. FEC and ACJ controls over Japan could continue but should not be strengthened.

Kennan's report found wide acceptance in Washington, sailing through the bureaucracy with only minor changes. The consensus reflected a general belief that the occupation had achieved its basic purposes of disarming Japan and laying a foundation for democratic government. In this sense, the occupation was over. In Europe the United States and its Allies had by 1946 veered sharply away from reform and punishment and toward economic recovery. By 1948 they were preparing to turn over most of their control in the western zones to a new German government. They might have liked to do the same in Japan, but the thought of dumping both MacArthur and the FEC made this option uninviting.

The general had a few comments on the Kennan report. Many were minor: U.S. occupation forces in Japan could not safely be reduced; occupation costs were not a heavy burden on the Japanese economy because they were devoted largely to construction of buildings, which

would be useful for the Japanese in the future; reducing the influence of the FEC and the ACJ was desirable; and war crimes trials could not be expedited. On a few points, however, he felt strongly. Any "expansion" of the police force would bring "explosive international reactions" in the FEC. He refused to alter purge policy, pointing out that it bore the approval of the FEC and that even though his execution of the policy had been "as mild as action of this sort conceivably could be," he had been bitterly attacked by five of the Allied nations for his "excessive mildness."[32]

Some of MacArthur's views resulted in modifications of the Kennan proposals. But the provisions regarding the police and the purge were retained much as originally drafted. These led to acerbic exchanges between Washington and Tokyo after the president approved the report on October 9, 1948. The State Department wanted to press MacArthur hard to carry out the provisions of NSC 13/2, and the Department of the Army went along reluctantly after watering down the wording of the messages to Tokyo.[33]

One stratagem was to send these instructions to MacArthur as U.S. commander in chief in the Far East (CINCFE) rather than as supreme commander for the Allied powers. MacArthur quickly rejoined that he had been designated an Allied commander by the Moscow agreement of 1945. Were the United States to breach this agreement by unilaterally sending him orders, other Allied powers might try to do the same. The Soviets might claim this right, "and with the present emasculated condition of our occupation force it is doubtful that we could successfully resist any thrust [they] might decide upon against Hokkaido or any other part of Japan." MacArthur added the telling comment that "NSC 13/2 has not been conveyed as an order to SCAP by appropriate directive prescribed by international agreement and therefore SCAP is not responsible in any way for its implementation."[34] These hard-hitting messages, which were drafted by Whitney, smacked of insubordination. They did not deter State and Army. These departments knew, as did MacArthur, that the occupation was a U.S. show, and they were determined that American policy would prevail. On February 15, 1949, Washington informed Tokyo that several sections of the basic directive of November 3, 1945, regarding the purge had been rescinded, as had the important provision that the supreme commander should take no responsibility for the economic rehabilitation of Japan. These policy adjustments had little impact on MacArthur, who had decided three years earlier to ignore the injunction against economic help for Japan.

On May 2, 1949, the State Department made an internal report on the implementation of NSC 13/2, six months after the president approved it. The internal report gave MacArthur low marks for his performance: no action had been taken to reduce the psychological impact of the occupation, no specific steps had been taken to prepare long-term plans for Okinawa or to improve the facilities there, and Japanese police had been issued more pistols, but nothing had been done to set up a national investigation bureau or to increase coordination of police operations around the country.[35] Nor had there been any reduction of SCAP's supervisory role over the Japanese government. In fact, SCAP had stated that greater stress on economic recovery had "completely reversed this policy." The purge had not been modified. Occupation costs had not been reduced. Only two actions were being taken to carry out the policy: intensive efforts were being devoted to economic recovery, and precensorship of the press had been terminated.

As he often did, MacArthur decided to implement the policy his own way without acknowledging Washington's role. On May 6, 1949, he ordered all headquarters sections to review outstanding directives and procedures for the purpose of relaxing controls and stimulating a sense of self-reliance and responsibility among the Japanese. Without mentioning the NSC policy paper, MacArthur based his order on his own press statement of May 2, 1949, on the second anniversary of the Japanese constitution, in which he proclaimed, "In these two years the character of the occupation has gradually changed from the stern rigidity of a military operation to the friendly guidance of a protective force. While insisting upon the firm adherence to the course delineated by existing Allied policy and directive, it is my purpose to continue to advance this transition."[36]

One of MacArthur's senior staff officers later described this program as "little more than window-dressing." But he did point out that SCAP took a number of actions under this order to reduce its operations and interventions in Japanese activities. In particular, it reduced the civilian employee element of the occupation from 3,660 to 1,950. It removed civil affairs teams—formerly known as military government teams— from prefectural capitals and cut their personnel drastically from 2,758 to 526.[37] Moreover, SCAP continued to give the police more pistols and training. The Japanese government was permitted to establish an appeals board to review purge cases, although its jurisdiction was restricted.

A number of American and Japanese historians have labeled Kennan

the master planner of a new policy of reverse course designed to implicate Japan in cold war politics. Kennan would have denied that his proposals were designed to turn back the clock on reform, although he did say later he could understand how younger scholars might feel he had taken a stern attitude regarding U.S. policy toward Japan. He believed that the reforms should be retained, some in modified form, and that the time had come for the Japanese to implement the reforms their way so long as they did not try to undo them. Nor would he have understood the argument that his policies were intended to embroil Japan in the U.S. rivalry with the Soviet Union.

Kennan's goal was to help Japan build adequate political stability and economic strength to make its way after negotiation of a peace treaty, which was already an active item on the Allied agenda. He felt Japan had to have better protection against internal threats to its security, especially a more effective police force, and he was willing to sanction firm but legal measures to control communists and left-wingers. Kennan did think a number of occupation reforms went too far, but he made no effort to change them. Nor did he take part in any group lobbying for change.

Consistent with his view that containment was a political, not a military, policy he made no recommendation that Japan should develop military forces or even that the United States should station forces in Japan after the peace treaty. He said in his Memoirs that "it was my hope—shared at the moment, I believe, by General MacArthur—that we would eventually be able to arrive at some understanding with the Russians, relating to the security of the northwestern Pacific area, which would make this unnecessary."[38] These were hardly cold war polemics.

Kennan left himself a loophole on the crucial issue of rearmament. Two days after meeting MacArthur, he inserted an explanatory note in his report that said in part that because of the Soviet threat and Japan's internal weakness (he considered Japan much more vulnerable to communist pressure than MacArthur did), Japan could not be left defenseless after a peace treaty; either there should be no treaty, or "we must permit Japan to rearm to the extent that it would no longer constitute an open invitation to military aggression." He added that if the USSR's military-political potential became less threatening in the future, then a treaty of demilitarization with Japan would be feasible.[39]

Kennan wrote later that his efforts in 1948 made "a major contribution to the change in occupational policy that was carried out in late 1948 and 1949; and I consider my part in bringing about this change to

have been, after the Marshall Plan, the most significant constructive contribution I was ever able to make in government. On no other occasion, with that one exception, did I ever make recommendations of such scope and import; and on no other occasion did my recommendations meet with such wide, indeed almost complete, acceptance."[40]

Kennan was not optimistic about the situation. In a talk he gave at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in October 1949, he said that Japan would have to make a "drastic adjustment" after the occupation and would face a "dangerous situation" in Asia because the country had been demilitarized. He felt there was a likelihood of reversion to an "extreme form of nationalism" and to a "totalitarian government," which did not bode well for the United States.[41]

The State and Defense departments did accept and apply the proposals in NSC 13/2, but MacArthur all but shunned them. They did not circulate in SCAP headquarters as new policy for the conduct of the occupation. MacArthur did not mention Kennan or NSC 13/2 in his Reminiscences . Yet he understood that Washington had decided on a shift in course. In a remark to Sebald on August 15, 1949, MacArthur said he was implementing the NSC policy as rapidly as possible, thus preparing Japan for eventual return of sovereignty.[42] And the new Japanese government, without knowing the bureaucratic tangle inside the U.S. government, welcomed the revised U.S. approach, which soon became evident despite MacArthur's shunning.

1.

Autographed photograph of General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor

Hirohito at their first meeting, September 27, 1945. Courtesy of MacArthur

Memorial Archives, Norfolk, Virginia.

2.

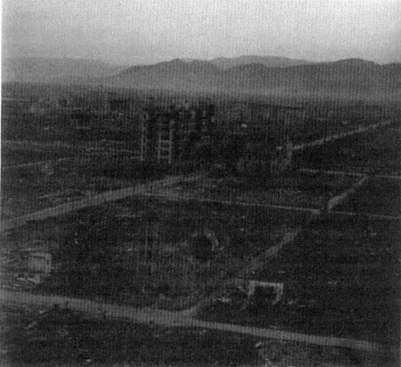

Aerial photograph of Hiroshima (taken December 22, 1945). Note the

church in the foreground. Courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, D.C.

3.

MacArthur relaxing. Courtesy of the Thames Collection.

4.

MacArthur greeting John Foster Dulles on his first trip to Japan, June 21,

1950. Ambassador W. J. Sebald is at right. Courtesy of the National Archives,

Washington, D.C.

5.

Dulles, Sebald, and Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru in conversation at a

reception in Tokyo, January 21, 1951. Courtesy of the National Archives,

Washington, D.C.

6.

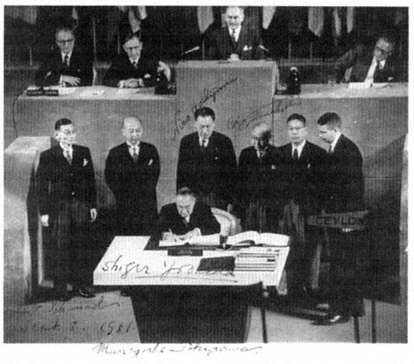

Prime Minister Yoshida signing the peace treaty, as his co-signers—

Ichimada Hisato of the Bank of Japan, Tokugawa Muneyoshi of the House of

Councillors, Hoshijima Nito and Tomabechi Gizo of the House of Representa-

tives, and Finance Minister Ikeda Hayato—look on. Secretary of State Dean

Acheson sits in the middle behind them. Courtesy of MacArthur Memorial Ar-

chives, Norfolk, Virginia.

7.

Prime Minister Yoshida signing the security treaty on September 8, 1951, at

the San Francisco Presidio. Looking on are Dulles, Secretary of State Dean

Acheson, and Senator H. Styles Bridges, ranking minority member of the Senate

Armed Services Committee. Courtesy of the National Archives, Washington,

D.C.

8.

Yoshida's calligraphy. Yoshida Shigeru was well known for his calligraphy.

He penned this quotation from the opening chapter of the Analects of Con-

fucius in 1955 as a gift to the new International House in Tokyo, where it is

now displayed. It means "Is it not delightful to have friends coming from distant

quarters?" (Legge's translation). Courtesy of International House, Tokyo.

9.

Two old friends. MacArthur and Yoshida meet at the Waldorf-Astoria on

November 5, 1954. Courtesy of Wide World Photos.

10.

Yoshida in retirement at Oiso. Courtesy of Asahi shimbun.

Photograph by Yoshioka Senzo.