Different Labor Systems, Diverse Gold Seekers

Not all miners, even in the early phase of the Gold Rush, were freewheeling independent entrepreneurs. As Susan Johnson has put it, "work in the diggings proceeded according to a dizzying array of systems that included independent prospecting and mining partnerships as well as altered Miwok gathering practices, Latin American peonage, North American slavery, and, later, Chinese indentured labor."[25] In the case of African Americans, a significant number of free blacks joined the Gold Rush. Some were seamen deserting vessels arriving from New England ports, while others made their way to California as employees or servants of overland joint-stock companies. But just as commonly, African Americans arrived in California as slaves to their gold-seeking masters. Rudolph Lapp estimates that 962, or approximately 50 percent of the African Americans in California in 1850, were slaves.[26]

We will never know precisely how many of the at least 15,000 Mexicans (10,000 from the province of Sonora alone) came as unfree laborers sponsored by patrones . Leonard Pitt asserts that "the north Mexican patrons themselves encouraged the migration of peons by sponsoring expeditions of twenty or thirty underlings at a time, giving them full upkeep in return for half of their gold findings in California."[27] The patrón system was also responsible for bringing a certain (unknown) proportion of miners to the diggings from Chile and Peru.

The Chinese did not arrive at the diggings quite as early as the Mexicans and South Americans. In 1850 there were only 500 Chinese miners in California, and 1,000 Chinese people in the entire United States.[28] However, in 1852 alone, 20,000 Chinese people entered California, most of them en route to the mining counties. By one contemporary estimate there were 20,000 Chinese miners in California by 18557.[29] Many of the first Chinese migrants were merchants able to pay their way from China. Others were not so fortunate. Most of the Chinese who emigrated to the United

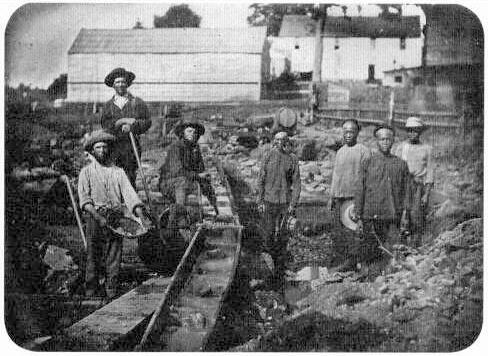

American and Chinese miners work a claim at the head of Auburn Ravine with a line

of sluice boxes in 1852. Woods Dry Diggings, as Auburn was originally named, was

one of the earliest mining camps in California, established in May 1848 when Claude

Chana and a party of Indians discovered gold in the ravine. Chinese merchants

contributed to the growth of the town, and several of their old wooden shops, dating

to the year of this daguerreotype, still stand on Sacramento Street. Courtesy California

State Library .

States did not experience the exploitation of the notorious "coolie" system, which bound workers to sign contracts agreeing to work in a foreign land for a specified time in return for their passage. Instead, most Chinese workers paid for their passage by what Sucheng Chan calls the "credit-ticket system," whereby Chinese middlemen paid the passage of emigrants in advance. In return, the emigrants contracted to pay their debts after arrival, with the prospect that the emigrants could keep their earnings after debts were paid.[30] While more research is needed to determine more precisely what proportion of Chinese emigrants arrived under the credit-ticket system, historian Elmer Sandmeyer asserts with confidence that "the evidence is conclusive that by far the majority of Chinese who came to California had their transportation provided by others and bound themselves to make repayment."[31] Indeed, the consensus of other historians is that the labor of indebted passengers was sold through Chinese subcontractors to Chinese mining companies, although some describe the labor system and working conditions of these Chinese as akin to debt peonage.[32]

In part, as Leonard Pitt has argued, the "free labor" preferences of white Americans contributed to the xenophobia and racism that most foreign miners (as well, of course, as Native Americans and Californios) encountered.[33] But there were other reasons why white American-born miners often had no compunction about expelling foreign miners, especially racial minorities, from the diggings and from mining towns. First, the American miners, conscious of the fact that access to gold was limited, resented the fact that the mining experience of peoples from Mexico, Chile, and Peru often made them more successful prospectors. Second, the belief in Manifest Destiny, reinfused by the United States's victory in the Mexican-American War, led many Americans to presume that they had priority at the diggings. Third, even while hostility and violence were also directed at white foreign nationals such as the French and Australians, the depths of racist ideology cannot be overemphasized. Indeed, as more and more historians have demonstrated, racist ideology was a crucial building-block in the making of white working-class consciousness.[34] Finally, as wage labor became more and more common in the mines, the disillusioned American Argonauts resented the competition of cheaper "foreign" labor. This contributed to the expulsion of many Native Americans in the early gold-rush years and was a source of tension between white and Chinese miners throughout the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s.[35]

In general, minorities suffered most from extra-legal forms of violence, but in the early 1850s white miners had the political clout to impose "legal" forms of discrimination on their rivals. This came in the form of two foreign miners' tax measures that were passed by the state legislature. The first, enacted in 1850, required miners who were not citizens of the United States to pay a licensing fee of $20 a month. Targeted particularly at Mexicans, this measure led to violence and the eventual departure of about 10,000 Mexican miners to their homeland in 1850.[36] The protests of many American merchants who lost customers as a result of the measure led to its repeal in 1851, but the influx of Chinese in 1852 prompted the passage of another act that provided for a tax of $3 per month, later raised to $4.[37]

While not a target of foreign miners' taxes, Native Americans suffered extreme violence at the hands of Argonauts from many nations. California Indian labor played a particularly important role in the early gold-rush years. The best estimate is that by the summer of 1848 perhaps half of the 4,000 miners were Indians. Even before the Gold Rush, Anglo-Americans and other immigrants in Hispanic California were quick to imitate the Mexican system of Indian labor exploitation. A group of pioneers such as John Sutter and John Bidwell simply moved their Indian labor force from their ranchos to the mines. There were reports of individual whites employing up to one hundred Indians at the diggings.[38]

Not all Indians worked for whites. Some were independent miners who bartered their gold dust with merchants on increasingly favorable terms as they came to ap-

preciate the value that the white man attached to it. But the Indian presence as independent and employed miners was short-lived. As Albert Hurtado and others have shown, newly arriving white miners from Oregon and other parts bitterly resented the advantage that ranchero employers of Indians had. Starting in 1849, and using indiscriminate and extreme violence, they drove most Indians from the mines. The 1852 state census showed that, with the exception of the southern mining counties, Indians made up a relatively small proportion of the population of the mining counties. Outside the southern mining counties, they constituted less than 10 percent of the population in every mining county but one. In these counties, probably only a small proportion of the Indians still present worked in the mines, and in most cases, historians agree, they usually worked for white miners. In the Southern Mines the Indians' numerical superiority prevented whites from driving them out during the early 1850s, but in time "attrition caused by disease, gradual displacement, and only occasional fighting would make the south a white man's country."[39]