6

Government Inhibits Medical Device Discovery: Product Liability

Personal injury law allocates responsibility for the costs of accidents.[1]

I use the term personal injury law to refer to both product liability and negligence—two different theories of liability. Technically, product liability refers to the legal theory of liability derived from strict liability, which assesses responsibility for defective products without concern for fault. Negligence, on the other hand, is a separate legal theory where liability is assessed on the basis of fault. Medical device producers, indeed all product producers, can be held liable under either theory. Both are discussed in greater detail in this chapter.

In product related cases, injured individuals (plaintiffs) seek to shift the costs to the producers (defendants).[2]Plaintiffs generally sue everyone in the chain of distribution—manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and others. This discussion focuses on manufacturers.

This area of law expanded dramatically during the 1970s. The rules of liability changed so that more injured consumers had the opportunity to prevail, and the size of the awards to victorious plaintiffs tended to rise as well. The increased risk of being sued introduced new uncertainties for manufacturers and created additional potential burdens for innovators.This increase in liability exposure occurred at the same time that medical device regulation emerged. Regulation and liability share a common goal—to deter the production of products that do not meet a standard of safety. However, these two institutions accomplish the goal in vastly different ways. Federal regulation is uniform and national. Much of the FDA's device regulation is prospective, that is, the rule is known before the manufacturer begins to market the product. (Of course, if problems arise in the marketplace, the FDA does have postmarketing surveillance power.)[3]

See discussion of the FDA in chapter 5.

In contrast, liability laws vary from state to state, subjecting producers to fifty different possible sets of rules. Liability is retrospective, in that the process begins after the harm occurs. Finally, the institutions use different standards and mechanisms to determine safety. The FDA imposes primarily scientific evaluation; judges and juries apply principles rooted in law and experience rather than in science. In addition to deterrence, liability law seeks to compensate victims for the costs of the injury, leading to damage awards. Product liability also has a

punitive component—the system can impose punitive damages for behavior that is particularly reprehensible.

This chapter describes the evolution of product liability law in the 1970s and the impact of those changes on medical devices. The cases of the A. H. Robins Dalkon Shield and the Pfizer-Shiley heart valve illustrate some important issues raised by liability litigation. Once again, a caveat is in order. Assessment of the impact of liability on producers is hampered by the lack of reliable data.[4]

The lack of reliable data is substantial, a problem noted and discussed in two major studies of product liability trends. The Rand Corporation, Institute for Civil Justice issued a study by Terry Dungworth, Product Liability and the Business Sector: Litigation Trends in Federal Courts, R-3668-ICI (1989) and the General Accounting Office, Briefing Report to the Chairman, House Subcommittee on Commerce, Consumer Protection, and Competitiveness, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Product Liability: Extent of 'Litigation Explosion' in Federal Courts Questions, GAO-HRD-88-36BR (January 1988). Both studies focus on federal court filings because the data are more accessible than in state courts, where records are not uniform and are difficult to acquire. In addition, corporate and insurance company records are confidential, and data about litigation costs or settlement amounts are not disclosed.

Information on settlements and litigation costs are confidential; court records are inconsistent in different states and are difficult to obtain. In addition, because of the diversity in legal requirements from state to state, generalizations about legal trends are limited. Finally, because liability rules can change with each court decision and can be altered by state or federal legislation or by voter initiative,[5]Traditionally, this area of law was dominated by common-law principles, that is, law that evolves through the judicial interpretation of precedents or previous court decisions. In state court, a state legislature can pass statutes that supercede the common-law principles; these statutes are then enforced by the court. In some states, such as California, there are also ballot initiatives that are voted on by the electorate. If the initiative passes, it becomes law and must be enforced by the court. Frequently, the courts are called upon to interpret unclear provisions in the statutes, which they must do in order to enforce the law.

the target is a moving one. Nevertheless, trends can be identified and some conclusions can be drawn.Breaking Legal Barriers

Changing Theories of Liability

Until the early 1960s, there were substantial barriers to successful legal claims for injuries related to products. Several legal trends broke down those barriers so that injured individuals could more readily prevail against producers.

Negligence

To win a negligence case, the plaintiff must prove that a defendant's behavior failed to meet a legal standard of conduct and that the behavior caused the plaintiff's harm.[6]

These are called the elements of the case. The plaintiff must plead all the required elements in the complaint filed in the court and must prove them all to win. For further reading of tort law, see G. Edward White, Tort Law in America: An Intellectual History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). For a law and economics perspective, see Guido Calabresi, The Costs of Accidents: A Legal and Economic Analysis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970). For a basic primer on the rules of tort law, see Edward J. Kionka, Torts in a Nutshell: Injuries to Persons and Property (St. Paul, Minn.: West, 1977).

Until the mid-nineteenth century, negligence "was the merest dot on the law."[7]Jethro K. Lieberman, The Litigious Society (New York: Basic Books, 1981), 35.

Negligence is a neutral concept, one that need not give advantage to a corporate defendant or an individual plaintiff. However, as negligence law evolved in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it supported the risk-taking behavior of industrial entrepreneurs and fit nicely within the ethic of individualism and laissez-faire.[8]For an interesting discussion of the history of American law, see Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1780-1860 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977), especially chaps. 6-7. See also Grant Gilmore, The Ages of American Law (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977); and Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973).

Judges considered the values of economic progress; they often carefully circumscribed the defendant'sduty of care and provided nearly impenetrable defenses.[9]

With a circumscribed standard of care, it was difficult for the plaintiff to show that the defendant's conduct fell below the legally imposed standard of behavior. Defenses that the defendant could raise included contributory negligence (if the plaintiff contributed even in a minor way to his own injury, he would automatically lose) and assumption of risk (certain activities are assumed to be risky, and the plaintiff must bear the consequences of those risks he undertakes). A good defense protected defendants from liability.

With negligence law so limited, most cases involving product injuries relied on the rules of contract, which were quite limited in their own right.[10]For example, the law required that the plaintiff be a party to the contract in order to sue, thus spouses or children of the person who signed the contract for product purchase could not bring an action. This is called privity of contract. Contract remedies, or the amount of money that can be claimed, also were narrowly defined by contemporary personal injury standards.

Yet, there were pressures to protect individuals injured by industrial progress. These forces increased as accidents involving railroads rose. One change in direction came in 1916, when Benjamin Cardozo, chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals, overthrew the doctrine of privity in the famous case of MacPherson v. Buick . A wooden automobile wheel collapsed, injuring the driver. MacPherson, the driver, sued Buick Motor Company, which had negligently failed to inspect and discover the defect. Buick's defense was that the company had no contractual relationship with MacPherson, that is, no privity of contract, because he had bought the car from a dealer, not directly from Buick. Cardozo held the manufacturer's duty of care was owed to all those who might ultimately use the product. This was a first step in the process that broke down contract law barriers placed in the way of injured persons.

A host of other doctrines, too numerous to describe here, began over the next fifty years to shift the balance in favor of the plaintiffs. By the 1960s, many state courts had greatly expanded the scope of duties owed to others, had abolished defenses available to defendants, and had begun to assess significantly higher damage awards.[11]

For example, California eliminated the defense of contributory negligence in Li v. Yellow Cab, 13C. 3d 804 (1970). Now plaintiffs can prevail even if they contributed to their own harm, but their damages will be reduced by the percentage share that is attributed to their own behavior.

Product Liability

Courts began to reflect frustration with the limitations on plaintiffs under traditional contract and negligence principles. These frustrations help to explain the development of the concept of strict liability and its applicability to producers.

Strict liability (called product liability when applied to product cases) differs from negligence in that it is not premised on fault. The doctrine looks to the nature of the product, not the behavior of the producer. If a product is found to be defective when placed in the stream of commerce, the producer may be liable for the harm that it causes, regardless of fault. Determining the parameters of the concept of defect is pivotal in these

cases.[12]

Although the principles vary from state to state, a product can be considered defective if its design leads to harm or if there is a failure to adequately warn the user of its risks.

Although strict liability had existed in the law since the nineteenth century, the theory became crucial in relation to product cases in the 1960s.The California Supreme Court led the way when it announced the standard of strict tort liability for personal injuries caused by products in Greenman v. Yuba Power Products . The court held the defendant manufacturer liable for injuries caused by the defective design and construction of a home power tool. Liability was imposed irrespective of the traditional limits on warranties derived from contract law. The court stated that "[a] manufacturer is strictly liable in tort when an article he places in the market, knowing that it is to be used without inspection for defects, proves to have a defect that causes injury to a human being."[13]

59 Cal. 2d 57, at 62. A few years earlier, in a dissenting opinion in Escola v. Coca Cola Bottling Co., Justice Traynor of the California Supreme Court set forth the grounds for the strict liability standard for product defects that was adopted by a large majority of jurisdictions nearly two decades later. While this dissent was largely ignored, it planted the seeds for the subsequent revolution. 24 Cal. 2d 453, 461 (1944).

Virtually every state subsequently adopted these principles of liability. Indeed, only one year after the Greenman case, the American Law Institute (ALI), which represents a prestigious body of legal scholars, adopted section 402A of the Restatement (Second) of Torts , which sets forth the strict liability standard.[14]

The American Law Institute (ALI) does not make law. However, distinguished scholars have traditionally analyzed and evaluated trends in the law and compiled them in books known as Restatements. The Restatements are not binding on courts. However, they are frequently consulted by judges in the course of drafting opinions, are very influential, and are often cited by judges for support in altering common-law principles.

The theory of strict liability has been elaborated and refined in various jurisdictions, including the definition of defect, the extension of the concept of defect to product design, the notion of defective warnings, and the restrictions on defenses available to the manufacturers and the duties of manufacturers when consumers misuse the product.[15]For a comprehensive discussion of the theory of product liability, see George Priest, "The Invention of Enterprise Liability: A Critical History of the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Tort Law," Journal of Legal Studies 14 (1985): 461-527. See also James A. Henderson and Theodore Eisenberg, "The Quiet Revolution in Products Liability: An Empirical Study of Legal Change," UCLA Law Review 37 (1990): 479-553.

In general, courts have held that a showing of a defect which caused[16]

What constitutes legal causation is another area fraught with controversy but is beyond the scope of our discussion. For those who want to understand the debate, see Steven Shavell, "An Analysis of Causation and the Scope of Liability in the Law of Torts," Journal of Legal Studies 9 (June 1980): 463-516.

injury is sufficient to justify strict liability. There are three basic categories of product defects. The first is a flaw in manufacturing that causes a product to differ from the intended result of the producer. The second is a design defect that causes a product to fail to perform as safely as a consumer would expect or that creates risks that outweigh the benefits of the intended design. The third arises when a product is dangerous because it lacks adequate instructions or warnings. Cases may be brought under one or more of these categories.Damage Awards

If a plaintiff wins the case, the next step is to assess the amount of damages to which he or she is entitled. The jury can award

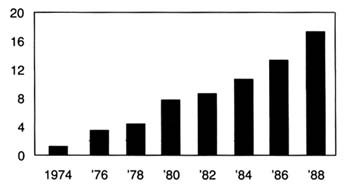

Figure 19.

Product liability suits filed in federal district courts (in thousands).

Source: Administrative Office of U.S. Courts. Reprinted from

Wall Street Journal, 22 August 1989, A 16.

damages for actual out-of-pocket losses, such as medical expenses, lost wages, and property damages. In addition, juries can include noneconomic damages, such as the value of the pain and suffering of the plaintiff, a subjective judgment that can add significantly to the total award amount. The amount awarded in jury verdicts has been increasing steadily since the 1960s, and much of this increase can be attributed to medical malpractice and product liability cases.[17]

Once again, a caveat on the reliability of data. Of the millions of insurance claims filed each year, only 2 percent are resolved through lawsuits. Less than 5 percent of the cases that are tried reach a verdict; the rest are settled. See Ivy E. Broder, "Characteristics of Million Dollar Awards: Jury Verdicts and Final Disbursements," Justice System Journal 11 (Winter 1986): 353. Many jury verdicts do not reflect what the plaintiff actually receives because these awards can be reduced on appeal. Jury awards are used as a benchmark for settlement amounts, however, and do reflect broader trends. See discussion in Robert Litan, Peter Swire, and Clifford Winston, "The U.S. Liability System: Backgrounds and Trends," in Robert Litan and Clifford Winston, eds., Liability: Perspectives and Policy (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1988).

(See figure 19 and table 8.)Punitive damages are another controversial area of liability law. Theoretically, punitive damages are intended to punish wrongdoers whose conduct is particularly reprehensible. They are added on top of the award of actual damages, which are intended to fully compensate the plaintiff for losses incurred. The standards for assessing conduct are relatively vague and require few limits.[18]

For a review of the principles of punitive damages, see Jane Mallor and Barry Roberts, "Punitive Damages: Toward a Principled Approach," Hastings Law Journal 31 (1980): 641-670. See also Richard J. Mahoney and Stephen P. Littlejohn, "Innovation on Trial: Punitive Damages Versus New Products," Science 246 (15 December 1989): 1395-1399.

For many years, punitive damages played a minor role in American law. As late as 1955, the largest punitive damage verdict in the history of California was only $75,000.[19]See discussion in Andrew L. Frey, "Do Punitives Fit the Crime?" National Law Journal, 9 October 1989, 13-14.

By the 1970s, however, punitive damages were frequently awarded, with many verdicts well over one million dollars.[20]See "Punitive Damages: How Much Is Too Much?" Business Week, 27 March 1989, 54-55.

There is considerable debate about why the liability laws changed in this way. Edward H. Levi of the University of Chicago identifies forces within the social experience of America. He believes that holding producers responsible for injuries

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

reflects views of the 1930s, when government control was increasing generally and greater government responsibility for individual welfare was thought proper.[21]

Edward H. Levi, "An Introduction to Legal Reasoning," University of Chicago Law Review 15 (1948): 501-574.

Others have argued that the change was tied to the growing complexity of products, which made consumers less able to evaluate them on an individual basis, and to the rise of the U.S. welfare state, particularly after World War II.[22]Lester W. Feezer, "Tort Liability of Manufacturers and Vendors," Minnesota Law Review 10 (1925): 1-27.

Economists Landes and Posner have an economic explanation: shifting responsibility to producers was an efficient response to urbanization and a reflection of "internalizing" costs to efficiency in manufacturing.[23]William M. Landes and Richard A. Posner, The Economic Structure of Tort Law (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987).

Yale law professor George Priest takes the view that modern tort law reflects a consensus of the best methods for controlling the sources of injuries related to products. Under what he calls the "theory of enterprise liability," businesses are held responsible for losses resulting from products they introduce into commerce, reflecting the perceived appropriate relationship between product manufacturers and consumers as well as the role of internalizing costs to affect accident levels and how to distribute risk.[24]Priest, "Critical History," 463.

Clearly the reasons for these changes in the legal environment are complex and multiple. The extent of their impact is also controversial. Personal injury and product liability relate to all consumer products. However, pharmaceutical products have been singled out for special treatment under the law. Medical devices have not received similar consideration, although there are conflicting trends in recent court decisions.

Special Protection for Drugs, Not Devices

A special exception to strict liability has been carved out for drugs and vaccines because of their unique status in society. During debates at the American Law Institute regarding product liability, members proposed that drugs should be exempted from strict liability because it would be "against the public interest" because of the law's "very serious tendency to stifle medical research and testing." A comment (known as "comment k") following the relevant section in the Restatement provides that the producer of a properly manufactured prescription drug may be held liable for injuries caused by the product only if it was not accompanied by a warning of the dangers that the manufacturer

knew or should have known. The comment balances basic tort law considerations of deterrence, incentives for safety, and compensation by recognizing that drugs and vaccines are unavoidably unsafe. Comment k has been adopted in virtually all jurisdictions that have considered the matter.[25]

For detailed discussion of comment k, see Victor E. Schwartz, "Unavoidably Unsafe Products: Clarifying the Meaning and Policy Behind Comment K," Washington and Lee Law Review 42 (1985): 1139-1148, and Joseph A. Page, "Generic Product Risks: The Case Against Comment K and for Strict Tort Liability," New York University Law Review 58 (1983): 853-891. The California Supreme Court recently disapproved the holding in a prior case which would have conditioned the application of the exemption under certain circumstances. California came down squarely on the side of comment k. In holding that a drug manufacturer's liability for a design defect in a drug should not be measured by strict liability, the court reasoned that "because of the public interest in the development, availability, and reasonable price of drugs, the appropriate test for determining responsibility is comment k.... Public policy favors the development and marketing of beneficial new drugs, even though some risks, perhaps serious ones, might accompany their introduction, because drugs can save lives and reduce pain and suffering." Brown v. Superior Court, 44C 3d 1049, 245 Cal. Rptr. 412 (31 March 1988) at 1059.

Of course, as pharmaceutical manufacturers would be the first to say, the comment k exemption does not eliminate liability exposure. Drugs and vaccines may be exempt from design defect claims, but producers may still be held liable for failure to warn and for negligence. Because pharmaceutical products account for many of the liability actions, this exemption is quite limited in practice.[26]

The GAO report found that drug products, including bendectin, a morning sickness drug, DES, a synthetic hormone used to prevent miscarriage, and Oraflex, an arthritis medicine, accounted for significant amounts of product liability litigation. GAO, "Product Liability," 12.

Generally speaking, medical devices have been treated like all other consumer products with regard to both negligence and strict liability in most jurisdictions. A handful of cases from scattered courts, however, have grappled with the relationship of the special exemption for drugs under comment k to other medical products like medical devices. Three cases involve injuries from IUDs. While these cases do not presage any major shifts in the case law, they do provide some insight on the thorny problem of distinguishing drugs from devices in the policymaking process.

In Terhune v. A. H. Robins,[ 27]

90 Wash. 2d 9 (1978).

the plaintiff suffered injuries from a Dalkon Shield. She argued that A. H. Robins had failed to warn her of the risks associated with the product. The Washington State Supreme Court held that because the IUD is a prescription device, comment k applies. (The case was brought before the Medical Device Amendments had been implemented; the court said that the fact that there was no FDA approval before marketing was irrelevant.) Precedents held that the duty to warn of risks associated with prescription drugs ran only from manufacturer to physician. Prescription devices, which cannot be legally sold except to physicians, or under the prescription of a physician, are classified the same as prescription drugs for purposes of warning.The Oklahoma Supreme Court decided a similar case several years later. In McKee v. Moore,[28]

648 P.2d 21 (Okla. 1982).

the plaintiff was injured by a Lippes Loop, the IUD manufactured by Ortho Pharmaceutical. As in the Terhune case, the plaintiff alleged that the companyfailed to warn of side effects. The Oklahoma Supreme Court equated prescription drugs and devices: "[U]nlike most other products, however, prescription drugs and devices may cause unwanted side effects even though they have been carefully and properly manufactured."[29]

Ibid., 23.

The issue is somewhat different in the context of design defects. A California appellate court recently grappled with the differences between drugs and devices in the area of design. In Collins v. Ortho Pharmaceutical,[ 30]

231 Cal. Rptr. 396 (1986).

the plaintiff alleged that the Lippes Loop that injured her was defectively designed. The court, citing the Terhune and McKee cases, equated prescription drugs and prescription devices. These products have been determined to be unavoidably unsafe, said the court, because they are reviewed by the FDA and contain warnings about use. The discussion in the case seems to confuse the concept of a prescription product with the process of premarket approval. Of course, all drugs must undergo premarket approval by the FDA before marketing. However, as we know, the Medical Device Amendments do not require premarket screening for all devices. Indeed, the device IUDs, including the Lippes Loop, did not require PMAs when they entered the market in the early 1970s.[31]For discussion of the Medical Device Amendments, see chapter 4. All Class I and Class II devices, as well as those entering the market under the 510k provision, do not undergo safety and efficacy screening similar to drugs. Some of these products may be limited to prescriptions or have labeling requirements imposed, however.

To the extent that the court is assuming that the FDA's premarket approval confers the unavoidably unsafe status, the analogy to devices is inapt. However, the analogy does seem appropriate for Class III devices.Many unanswered questions remain. How much meaning does prescription confer? What about hospital equipment that is not prescribed per se, such as resuscitation equipment or monitoring apparatus? The answers are unclear, though there are important distinctions that the courts have not begun to consider.

Manufacturing defects are most frequently cited as the cause of injury in product-related suits arising from the use of medical devices. While it is increasingly common for strict liability claims to be brought in medical device cases, negligence continues to be the most common theory of recovery. The struggle in the courts on how to characterize medical devices for purposes of liability underscores the diversity of the products in the industry and the limited understanding of the relationship of devices to medical

care. It also recalls the thorny drug/device distinctions that FDA and Congress grappled with in crafting regulatory principles.

The Relationship of Device Liability to Medical Malpractice

Malpractice cases are brought under negligence theory. In a medical context, the plaintiff must show that the health professional's performance fell below the standard of care in the community. The impact of medical malpractice on the practice of medicine has been the subject of much debate, which is beyond the scope of this inquiry.[32]

For a discussion of medical malpractice, see Patricia Danzon, Medical Malpractice: Theory, Evidence, and Public Policy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985).

However, there is interaction between product liability and medical practice, and that interaction has consequences for medical device producers. Fear of malpractice claims has encouraged what is known as defensive medicine: the practitioner is cautious, often ordering batteries of tests that may not be medically necessary in order to protect against future claims. This behavior has led to overuse of some medical technology, including medical devices.Malpractice and product liability cases often are filed simultaneously. For example, in many IUD cases, women sue both their doctors and the product manufacturer. The manufacturer's liability is based on failure to warn of dangerous side effects or on production of a defectively designed product. A doctor's failure to inform the patient of risks associated with IUD use, failure to perform a thorough examination, negligent insertion or removal of an IUD, failure to warn of the risks of pregnancy when the device is in place, and failure to monitor the patient for adverse reactions can all establish claims.[33]

Guerry R. Thornton, Jr., "Intrauterine Devices: IUD Cases May Be Product Liability or Medical Negligence," Trial (November 1986): 44-48, 44.

Device manufacturers have replaced physicians as the most frequently named defendants in cases involving medical device use.[34]

Duane Gingerich, ed., Medical Product Liability: A Comprehensive Guide and Sourcebook (New York: F & S Press, 1981), 57.

In some instances, the physicians have allied with plaintiffs' attorneys against the manufacturer. In Airco v. Simmons First National Bank,[35]638 S.W. 2d 660 (Ark. 1982).

one of the largest medical device cases to date, the plaintiff's attorney was encouraged by the doctors whom he had charged with malpractice to sue the manufacturer of the anesthesiology equipment used in the surgery. The court held the manufacturer primarily liable for the death in the case. Airco and the physicians' partnership admitted liability for compensatorydamages shortly before trial. The jury assessed $1.07 million in damages against both defendants and $3 million in punitive damages against Airco. Airco's appeal of the punitive damages award was rejected by the Arkansas Supreme Court, which found a sufficient record to support the jury's findings of a design defect in the ventilator component of Airco's breathing apparatus.

A number of states have placed caps on malpractice awards available in the courts. Legislatively imposed caps on medical malpractice may increase the likelihood that medical device manufacturers will bear additional costs to compensate injured individuals.

The Impact on Device Innovation

There is no consensus on the size or extent of the liability crisis. Without entering that debate, it is possible to speculate on its impact on innovation in the device industry.

There is no question that the expansion of product liability has affected medical device producers. There is a greater likelihood of successful lawsuits against manufacturers and inevitably higher insurance premiums have resulted for all producers. Recently one defense attorney noted: "I'd be willing to bet that ten years ago there weren't five cases in the United States against medical device manufacturers. Now there are that many every day."[36]

David Lauter, "A New Rx for Liability," National Law Journal (15 August 1983), 1, 10.

While data are hard to come by, this comment captures the trend. The consensus is that device producers face significant liability exposure. In general, claims are on the rise, losses have increased, and recovery rates for plaintiffs have gone up.MEDMARC, an industry-owned insurance company for medical device manufacturers which has 440 members, may reflect the liability situation of the industry. The president of MEDMARC reported that claims rose 42 percent between 1986 and 1987. On average, the plaintiff recovery rate for hospital equipment cases is about 71 percent and for IUDs about 78 percent.[37]

Kathleen Doheny, "Liability Claims," Medical Device and Diagnostic Industry (June 1988): 58-61, quoting Jaxon White, President of Medmarc Insurance, Fairfax, Virginia.

Many producers and service providers have experienced exceptionally high increases in insurance premiums or have been denied coverage altogether. The industries most seriously affected include manufacturers of pharmaceutical and medicaldevices, hospitals, physicians, and those dealing with hazardous materials.[38]

Priest, "Critical History," 1582.

For example, Puritan-Bennett, a leading manufacturer of hospital equipment such as anesthesia devices, faced a 750 percent increase in insurance premiums in 1986, with less coverage and higher deductibles.[39]Michael Brody, "When Products Turn into Liabilities," Fortune, 3 March 1986, 20-24.

Both G. D. Searle, the manufacturer of the Copper 7 IUD, and Ortho Pharmaceutical, the producer of the Lippes Loop, claim that insurance and liability exposure caused them to withdraw their product.[40]Luigi Mastroianni, Jr., Peter J. Donaldson, and Thomas T. Kane, eds., Developing New Contraceptives: Obstacles and Opportunities (Washington D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990).

As one might expect, the device industry asserts that innovation is threatened by this legal environment. HIMA surveyed its membership to determine its views on product liability.[41]

Health Industry Manufacturers Association, "Product Liability Question Results" (Unpublished document, 14 October 1987). Forty-nine companies received the questionnaire, 39 responded. HIMA has two hundred member companies.

Of the respondents, most reported soaring insurance premiums, and 25 percent reported that product liability deterred them from pursuing new products, including products that would fall into FDA Class III or that require highly skilled practitioners. Other medical organizations support this view. The American Medical Association has concluded that product liability inhibits innovative research in the development of new medical technologies.[42]See Report BB (A-88), "Impact of Product Liability on the Development of New Medical Technologies" (Unpublished document of the American Medical Association, undated).

Although the data are incomplete, there is no question that the threat of product liability creates uncertainty. Except in instances of fraud or deception, producers may not know what long-term risks their products present. They may be underinsured or, in the present liability environment, unable to acquire insurance. Laws vary from state to state, laws change over time, and outcomes depend on a variety of factors unique to each case. The size of awards also varies greatly, even in instances where the actions of defendants are the same. Product liability can destroy a company or a product. However, even the most conscientious producer faces an uncertain liability future. The potential of liability policies to disrupt company operations is high. The following case studies illustrate the impact of liability laws on producers.

The Dalkon Shield

IUDs are probably the most controversial medical device in the United States. Chapter 4 discussed their entry and rapid distribution into the market in the early 1970s.[43]

See discussion in chapter 4.

By the mid-1980s, the technology had practically disappeared. The story of theDalkon Shield has been told elsewhere in great detail.[44]

See Morton Mintz, At Any Cost: Corporate Greed, Women, and the Dalkon Shield (New York: Pantheon, 1985); Susan Perry and Jim Dawson, Nightmare: Women and the Dalkon Shield (New York: Macmillan, 1985); and Sheldon Engelmayer and Robert Wagman, Lord's Justice: One Judge's Battle to Expose the Deadly Dalkon Shield IUD (New York: Doubleday, 1985).

It is discussed here to illustrate the impact of mass tort litigation on a firm.Few defend the actions of A. H. Robins Company, either in the marketing of the IUD or in its subsequent behavior after the product was withdrawn. It is generally agreed that Robins entered the contraceptive market without knowledge or experience. It relied on erroneous research data, ignored warnings of product risks, and denied the existence of evidence to the contrary. The court found serious wrongdoing on the part of the company, and an official court document affirmed "a strong prima facie case that [the] defendant, with the knowledge and participation of in-house counsel, has engaged in an ongoing fraud by knowingly misrepresenting the nature, quality, safety, and efficacy of the Dalkon Shield from 1970–1984."[45]

Hewitt v. A. H. Robins Co., No. 3-83-1291 (3rd Div. Minn., 21 February 1985).

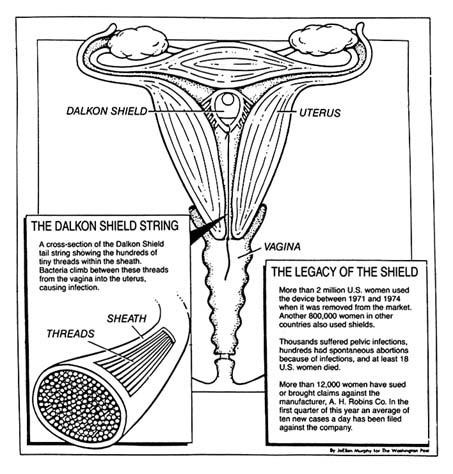

The problem with the product has been traced to its multifilament tail, a string attached to the plastic shield (see figure 20). The string allowed women to check that the product was in place and facilitated removal by a physician. This string was not an impervious strand but was composed of many strands that allowed bacteria to be drawn from body fluids into the uterus. The result was inflammation and infection, leading to illness, sterility, and, in some instances, death.[46]

Subrata N. Chakravarty, "Tunnel Vision," Forbes, 21 May 1984, 214-215.

The product was removed from the market in 1974, after several deaths and 110 cases of septic abortion (miscarriage caused by infection in the uterus). Then the lawsuits began. By June 1985, there were 9,230 claims settled and 5,100 pending; Robins had paid out $378 million at that time.

The cases continued to pour in. The company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in August 1985.[47]

New York Times, 22 August 1985, 36.

As part of the proceedings, a reorganization plan had to be approved, and it could not go into effect until it was clear that no legal challenges to it survived. A plan was finally approved at the end of 1989, more than four years after the initial bankruptcy filing.[48]Wall Street Journal, 7 November 1989, A3.

This action cleared the way for the acquisition of the company by American Home Products and the establishment of a trust fund of $2.3 billion to compensate women who had not yet settled their claims with Robins.The plan transferred all responsibility for the Dalkon Shield

Figure 20. The Dalkon Shield.

Source: Washington Post National Weekly, 6 May 1985, 6.

claims to the trust. The trust funds were available to resolve the remaining 112,814 claims pending in 1989.[49]

Alan Cooper, "Way Is Cleared for Robins Trust," National Law Journal, 20 November 1989, 3, 30.

Twenty years after the product was marketed and sixteen years after it had been removed, injured claimants still awaited compensation. In late 1989, a federal grand jury began a criminal investigation into allegations that Robins concealed information and obstructed civil litigation.[50]Ibid., 30.

The course of this litigation raises questions about the efficiency of the tort system to accomplish its goal to compensate for

injuries. It also raises issues of deterrence. Who has been deterred? Ideally, of course, only unscrupulous companies or producers of unsafe products should be deterred by liability law. However, it appears that bona fide contraception innovators have generally abandoned the market in the wake of these lawsuits. It is difficult to justify a liability system when its primary goals—compensation and deterrence—are not met.

Heart Valves

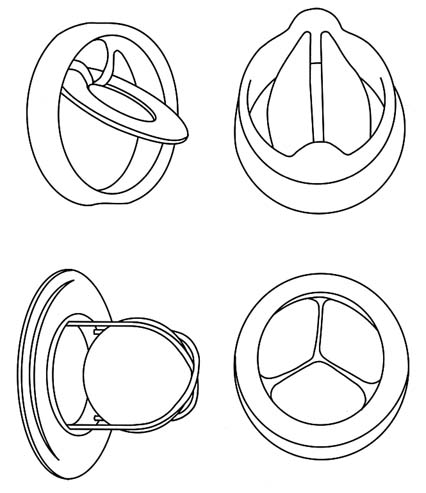

Another medical device controversy arose in 1990. This case involved the Bjork-Shiley Convexo-Concave heart valve. Heart valves regulate blood flow and are essential to an efficiently functioning heart. Defective valves can lead to constant fatigue, periodic congestive heart failure, and other ailments. The development of artificial replacement valves became a challenge to medical device producers.

In 1968, Dr. Viking O. Bjork, a Swedish professor, began working on mechanical heart valves to replace defective ones. Bjork provided the design, and the Shiley Company engineered and manufactured the valves. The design, a curved, quarter-size disk that tilted back and forth inside a metal ring, was intended to reduce the risk of blood clots, a significant problem with previous implants.[51]

Barry Meier, "Designer of Faulty Heart Valve Seeks Redemption in New Device," New York Times Science, 17 April 1990, B5-6.

Approximately 394 of the 85,000 valves of this design that were sold worldwide between 1978 and 1986 have failed. The problem involves fractures in the struts that are welded on the inside of the valve that controls blood flow through the heart (see figure 21).[52]By 1980, it was clear that some of the original valves that opened 60 degrees were malfunctioning. Bjork convinced Shiley that it should produce a 70 degree valve, which would offer improved flow. Shiley apparently remilled many of the 60 degree valves; these products were even more hazardous than those they replaced. None were sold in the United States, and they were removed from the world market in 1983. Approximately 4,000 overseas patients received the valves. By 1990, seventy had died. See discussion in Greg Rushford, "Pfizer's Telltale Heart Valve," Legal Times, 26 February 1990, 1, 10-13.

The engineering flaw that led to strut fracture in the valve caused 252 reported deaths.[53]Michael Waldholz, "Pfizer Inc. Says Its Reserves, Insurance Are Adequate to Cover Heart Valve Suits," Wall Street Journal, 26 February 1990.

Shiley stopped selling the valve in 1986. Over two hundred lawsuits have been filed; many more are expected.Several tentative conclusions can be drawn from this case, although many of the legal issues were still pending in 1990. First, policy proliferation contributed to the problem. The FDA had jurisdiction over the valves. Congress began investigating the FDA's role in 1990 and accused Shiley of continuing to market the valves even after officials became aware of the manufacturing problems. Apparently as early as 1980, Shiley urged FDA officials not to notify the public because of the anxiety it

Figure 21. Examples of artificial heart valves.

Source: Marti Asner, "Artificial Valves: A Heart-Rending Story,"

FDA Consumer 15:8 (October 1981), 5.

might cause patients with implanted valves. A congressional report criticized the FDA, asserting that it was too slow in removing the valves from the market and did not properly inform the public of the risks.[54]

Greg Rushford, "Pfizer Fires Opening Salvo in Its Public Defense," Legal Times, 5 March 1990, 6.

The allegations raise important questions about the ability of the FDA to oversee the marketplace.Another issue involves innovation. Will the legal liability facing Shiley deter others from entering the heart valve market or force current producers to withdraw from the market? Will the

heart valve market soon follow the decline of the IUD industry? Will important incremental improvements in a valuable lifesaving technology be lost? For example, 76,000 units of an improved Shiley monostrut (one-strut) valve have been used without failure in Europe since 1983. The FDA, claiming it needs more clinical data, has not yet approved this innovation. Is the FDA being overcautious because of the current controversy? Will this stance aggravate the deteriorating conditions for innovators?

Finally, one can ask whether litigation can resolve the dilemmas faced by patients. What about the individuals who have defective valves already implanted? They face life-threatening surgery to remove them or daily fear that the valve might fail. Does it matter that they might have died without access to the innovation in the first place? Do we have unrealistic expectations about the medical products that we use? Is the newfound anxiety legally recognizable? Some heart valve recipients have sued Pfizer on the grounds that they have increased "anxiety" knowing they are living with a defective valve. Some courts have recognized the viability of an anxiety claim, but only if Shiley engaged in fraudulent, rather than merely negligent, behavior.[55]

A fraud claim differs from negligence. Fraud requires that the defendant misrepresented the product, knowingly with intent to induce the plaintiff to enter into the transaction. When fraud is involved, rather than simple negligence, the court has held that claims for anxiety can be heard. See Khan v. Shiley, Inc., 226 Cal. Rptr. 106 (30 January 1990).

Assessing the Fate of Two Technologies: Pacemakers and IUDs Compared

The motivations for greater government involvement and the manner in which that involvement occurred can be illustrated by two postwar technologies—the cardiac pacemaker (see chapter 5) and the IUD. Both products had antecedents stretching back many decades, but the arrival of these modern implanted devices occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. In both cases, the products diffused rapidly and widely, so that several million women used the IUD by the mid-1970s and tens of thousands of cardiac patients had the early pacemakers implanted. There is a danger that a focus on these two technologies might skew our perceptions of the field because both generated much controversy, while thousands of other new medical devices received little or no public attention. However, comparison of these two products provides useful insights into the evolution of public policies that

potentially inhibit device discovery. The public debates these devices generated led to political pressure for device regulation and illustrate the impact of the new product liability system.

It is intriguing to note that the IUD and pacemaker industries evolved quite differently by the mid-1980s. In 1986, there was only one small manufacturer of IUDs and one new entrant on the horizon. All the other major producers had withdrawn from the market, and sales were only a fraction of what they had been ten years before. The market for cardiac pacemakers, on the other hand, has continued to boom. There have been many important technological improvements. While some producers generated controversy, primarily in regard to sales tactics, early entrants prospered and many new companies thrived.

The contrast between these two innovations helps us ask important questions about the role of regulation and product liability in device innovation. The contrasts raise tantalizing questions as to why technologies succeed or fail, providing insight into the future of device innovation.

The advent of FDA regulation in the mid-1970s and the simultaneous expansion of product liability in the state courts substantially altered the interaction of the private sector and government. Inventors and developers of products could not afford either to ignore regulatory intervention before marketing a product or to ignore the regulators and the courts if subsequent risks occurred.

Regulation alone did not significantly disrupt the industry as a whole, although smaller firms bore a disproportionate share of regulatory costs. Product liability exposure presented a more general threat, particularly for evolving complex technologies, including implanted devices. The threat of liability and adverse legal outcomes work to shift costs of injuries through insurance from the consumers to the producers of products.

Pacemakers and IUDs can provide insights into the impact of these two pervasive regulatory and liability policies on innovation. There are many similarities between these two devices. Both are innovative implanted products, although the cardiac pacemaker is more complex because of its need of a power source and the need for lead wires to the heart. Both products were produced by a range of competitors for what were believed

to be large markets. Both markets included large reputable firms, and innovative smaller companies. Both had unscrupulous firms. There is evidence, for example, that A. H. Robins intentionally falsified research data; Cordis Corporation has been accused of selling defective pacemakers with faulty batteries even after knowing of the defects. Four former Cordis officers have also been indicted for fraud.[56]

New York Times, 20 October 1988.

Both technologies were subjected to significant regulation through the Class III mechanism after the law was passed. Both products gave rise to thousands of lawsuits.Yet, by the mid-1980s, only the Alza Corporation remained in the IUD business, dominating a very small market that represented less than one-tenth the number of total sales in the IUD heyday of 1974. By contrast, the pacemaker market was booming. Medtronic, the company that pioneered the device, remained the industry leader, but many other companies maintained innovative and lucrative positions in the field.

How can we explain this disparity? What can we learn from these cases? First, the vulnerability of an innovation to adverse regulatory or product liability effects may depend on the nature of the risks the product presents. Adverse reactions to IUDs included death and sterility in young women who were otherwise healthy. Pacemakers, even if they malfunction, do not generally cause death, only a return of the symptoms.

Second, the risks presented by a product may relate not to the technology per se, but to its use by inappropriate candidates. Women for whom IUDs were inappropriate experienced severe reactions. Pacemakers implanted unnecessarily do not present greater risks than those implanted in patients who benefited from them. Also, pacemakers are used by individuals with serious preexisting medical conditions. IUDs are used by healthy young women. Adverse reactions in this population seem more unnecessary and devastating than reactions in elderly cardiac patients.

Third, both IUDs and pacemakers suffered from adverse publicity brought about by regulation and product liability cases. However, negative publicity may affect a product more if there are alternatives available for the consumers. Because there were

alternatives to IUDs, it was easier for users to abandon them and switch to contraceptive pills or other barrier forms of contraception. Pacemakers continued to fulfill a critical function for which no alternative existed.

Fourth, there may be contributory effects from other public policies. The widespread availability of public Medicare funds for pacemaker implantation could have played a role in keeping the market healthy, leading to greater incremental innovation and product improvement. The market issues relevant to pacemakers will be discussed in the following chapter. The IUD did not benefit from substantial third-party payment support.

Fifth, both regulation and liability are crude tools for the prevention of product risks. Regulation attempts to operate proactively by eliminating potential risks before marketing. Arguably, this process would screen out inappropriate products, eliminating the need for product liability. Clearly the regulatory process is imperfect, because not all risks are eliminated. And the more burdensome the regulation, the more likely that desirable innovations are deterred or deflected. Product liability, a retrospective risk-reduction tool, can seriously inhibit a product or a company that produces a subsequently discovered high-risk device. Product liability may deter legitimate innovators from entering important fields of research.

It is clear that the full force of regulation and liability does not inevitably eliminate innovations. The pacemaker has remained a viable product, even in the face of controversy, and incremental innovative improvements have been continuously produced. Although the IUD did not flourish, the technology remains viable. Indeed, the efforts of two small companies, Alza Corporation and GynoPharma, which are discussed in Chapter 7, illustrate how firms can adapt controversial technologies to the current regulatory and liability environment.

Indeed, as policies have proliferated, their effects on the industry can only be understood in relationship to one another. It seems clear that the introduction of policies to inhibit device discovery—regulation and product liability—have negative effects on some products. However, the whole free-spending environment generated by government payment policies tended

to blunt the impact of regulation and liability. This environment, however, began to change when cost control became the theme of the 1980s. When efforts to inhibit device distribution began in earnest, the potential for serious impacts on innovators emerged.