4—

In their vigorously metrical montage and their disconcerting effects on the viewer's perception, Paul Sharits's flicker films may seem diametrically opposed to the elegant and slow-paced films of Belson and Whitney (though, in fact, flicker effects occur in some of their films as well). What Sharits has done, however, is pick up where the planning for Li left off—not chronologically, since he had begun to make flicker films some fifteen years earlier—nor formally, since his films are based on alternating frames of solid color, not "writhing 'random' dot fields." But in conceptual terms, Sharits went in the direction Whitney had taken when he decided to make an imageless film that would stimulate the viewer's own image-making capacities.

Although at one level Sharits's flicker films continue to depict inner perception, at another level they set new perceptual processes into motion. As he explains in a statement for the Knokke-le-Zoute experimental film

festival of 1967, "In my cinema flashes of projected light initiate neural transmission as much as they are analogues of such transmission systems," and his description of Ray Gun Virus could be applied to his other flicker films as well: "Light-color-energy patterns generate internal time-shape and allow the viewer to become aware of the electrical-chemical functioning of his own nervous system."[41] The same could be said of other flicker films, such as Peter Kubelka's Arnulf Rainer , Standish Lawder's Raindance , Tony Conrad's The Flicker , Keith Rodan's Cinetude 2, and Pierre Hébert's Around Perception , as well as passages in films by Robert Breer, Kee Dewdney, Michael Snow, Brakhage, Belson, and Whitney (to mention a few of the many avant-garde filmmakers who have used flicker effects).

Strictly speaking, flicker effects are not in the film at all; they are merely stimulated by it. Alternating frames of black and white, for instance, will evoke perceptions of an ephemeral and slightly pulsating gray. Alternating red and blue frames produce a comparably vivid, yet insubstantial, violet. The perceived color and the rapid pulsations are created by the viewer's visual system in response to the order and frequency, as well as the brightness and hue, of the alternating frames. As the light continues to flicker, the whole image may seem to expand and contract and even lift itself off the surface of the screen and hover disconcertingly in some ambiguous plane that is impossible to fix in space. In fact, it is not "in space" at all. It is "in" the temporally organized firing of brain cells. It is quite literally an "internal time-shape," as Sharits calls it, created by "the electrical-chemical functioning of [the viewer's] own nervous system." The same might be said of all seeing, but usually there is a fairly strong resemblance, or iconic relationship, between the external stimulus and the internal representation of the stimulus. The viewer of a flicker film, however, sees things that are very different from what is in the film itself. For this reason, one might argue that flicker is the filmmaker's most effective means of generating images directly inside the viewer's mind—as Anger, Vanderbeek, Mekas, and others had sometimes hoped to do, though by other means.

By their very nature, then, all flicker films take advantage of the fact that perception of rapidly alternating patterns of light and dark can have powerful physiological and psychological effects. Among the more unpleasant effects are headaches, nausea, and even, for a very small number of people, epileptic seizures. For that reason, the following disclaimer at the beginning of The Flicker is only partially tongue-in-cheek:

WARNING. The producer, distributor and exhibitors waive all liability for physical or mental injury possibly caused by the motion picture 'The Flicker.'

Since this film may induce epileptic seizures or produce mild symptoms of shock treatment in certain persons, you are cautioned to remain in the theater only at your own risk. A physician should be in attendance.

On the other hand, as Conrad knew perfectly well, flicker can produce a broad range of pleasurable and even exhilarating effects. Experiments have shown that when a strong light flashing five to ten times per second is directed on closed eyelids, most subjects perceive constantly changing patterns of color.[42] In Heaven and Hell , Huxley compares these subjective perceptions to the visionary experience, and in an "Expanded Arts" issue of Film Culture , Jonas Mekas treats them as examples of "expanded" vision, quoting as evidence a particularly vivid account of the effects of a homemade "flicker machine":

Visions start with a kaleidoscope of colors on a plane in front of the eyes and gradually become more complex and beautiful, breaking like surf on a shore until whole patterns of color are pounding to get in. After a while the visions were permanently behind my eyes, and I was in the middle of the whole scene with limitless patterns being generated around me. There was an almost unbearable feeling of spatial movement for a while, but it was well worth getting through, for I found that when it stopped I was high above earth in a universal blaze of glory. Afterwards I found that my perception of the world around me had increased very notably.[43]

Although the precise reason for these effects is still unknown, there is no doubt that flicker can produce perceptions comparable to some of those experienced in hallucinations, meditation, and visionary experiences ("I was high above earth in a universal blaze of glory"), and is, therefore, an appropriate basis on which to construct films for the inner eye.

Some evidence to support such a claim was supplied by a series of experiments conducted in the early 1970s by Edward Small and Joseph Anderson. They found that watching a short film of alternating white circles and black frames "induced the perception of symmetrical, geometric, colored patterns which were strikingly similar to many of the mandala forms reproduced in various works."[44] Producing flicker with a circle rather than with full, rectangular frames undoubtedly encouraged perceptions of the mandala's circular shape, but when Small and Anderson asked their subjects to make drawings of what they saw while watching the film, most made circles containing "symmetrical, geometric" patterns characteristic of mandalas (even though, as the investigators were careful to determine, most of their subjects had never heard of mandalas and knew nothing of their traditional forms in other cultures).

Among avant-grade filmmakers who have made flicker films, Sharits is not only noteworthy for his persistence in exploring the aesthetic possibilities of flicker effects but also for his understanding of their relationship to visionary forms like the mandala. Because he realized that flicker was a cinematic technique capable of producing equivalents of visual experiences generated by mental processes alone, he specifically designed his flicker films to be "occasions for meditational-visionary experience," as he explains in his statement for the Knokke-le Zoute film festival in 1967.

Not surprisingly, mandalas play a significant role in the way Sharits conceptualized and attempts to describe his films. In addition to Piece Mandala/End War (1966), which Sharits calls a "temporal mandala" (and to which I will return for a more thorough discussion), there are also Razor Blades (1968), which begins, in Sharit's words, "as a mandala . . . [that] is visually sliced open"; N:O:T:H:I:N:G (1968), where the "color development is partially based on the Tibetan Mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas"; and T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968), which Sharits describes as "an uncutting and unscratching mandala." It is not the esoteric symbolism of mandalas that interested Sharits; rather, it is their "strong, intuitively developed imagist power," as he puts it. His flicker films exhibit some of that same power to stimulate and help shape the imagery of inner perception.

Piece Mandal/End War can serve as a concrete example of flicker films in general and the "meditational-visionary" experience aimed for by Sharits's flicker films in particular. A flickering dot at the beginning of the film introduces the flicker effect itself and at the same time embodies what Sharits calls the "circularity and simultaneity" that are the mandala's "tools for turning perception inward." Sharply perceived yet curiously tenuous, shadowy yet bright, the dot engages the viewer's perceptions in the temporal flow of the film while simultaneously revealing the discrete units of which that flow is composed. Rather than "IN as particle OUT as wave," as Whitney describes the concluding sequence of Wu Ming , the flicker-dot opening of Piece Mandala/End War is "particle" (the projector's discrete impulses of light) and "wave" (the fluttering persistence of the dot in the viewer's perception) at the same time.

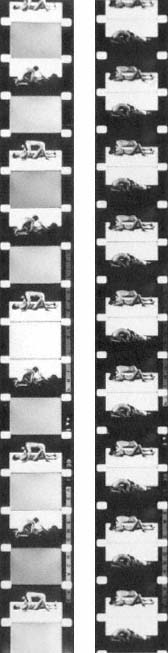

Formally, thematically, and perceptually the film as a whole, like all flicker films, rests on the paradox of discontinuous continuity, separateness and union. In Piece Mandala/End War , Sharits extends that paradox from flickering fields of color to flickering black and white frames composed of still photographs of a couple making love. These few separate frames (showing the man on hands and knees above the woman and crouched to perform cunnilingus) go through innumerable repetitions and

Sequences of discontinuous images produce flicker

and illusory movement in Piece Mandala/End War.

permutations. When the lovers' heads are oriented toward the left, the background is black in the top half and white in the bottom half; when the lovers' orientation is reversed, the background reverses to white at the top and black at the bottom. When shots from opposite sides of the lovers alternate frame-by-frame, the background flickers grayly or almost seems to spin vertically while the lovers' bodies appear to whirl horizontally and, at the most rapid rate of flicker, fuse into a single-double body with heads, arms, and legs at both ends. At some moments the black and white images of the lovers are suffused with subtly vibrating hues contributed by interjected frames of solid colors. In Sharits's description: "Blank color frequencies space out and optically feed-fuse into black and white images of one love-making gesture which is seen simultaneously from both sides of its space and both ends of its time."

Simultaneity of sequential moments may be a contradiction in terms, but the flicker effect gives it a kind of perceptual logic. The brain is forced to blend images that are not only temporally and spatially distinct but even mutually exclusive (such as figures facing left and right at the same time). Flicker breaks down such dichotomies as black/white, color/noncolor, left/right, bottom/top, beginning/ending, female/male.

In the middle of the film, however, the "circularity and simultaneity" is broken by flickering static images of a man (Sharits) raising a pistol to his head and pulling the trigger. The "bullet's" trajectory is traced in white animated dashes that hit the man's temple and then retreat back into the pistol's barrel; whereupon the man lowers the gun again. This doing and undoing of self-destruction is like a vertical line bisecting the "temporal mandala" of the film as a whole. At the same time, this seemingly intrusive image may be taken as an allusion to the perceptual violence of the flicker effect itself—indeed, of the whole process of projecting flickering light at viewers' eyes. While making his flicker films, Sharits was acutely aware of this form of violence. "The projector is an audio-visual pistol," he wrote in a note on Ray Gun Virus; "The retinal screen is a target. Goal: the temporary assassination of the viewer's normative consciousness."

In normal film-viewing situations, the projector-pistol also fires discontinuous impulses of light at the viewer's eyes but usually at a sufficiently rapid rate to disguise their discontinuity. (This is one of the projector's major contributions to the "grand scheme" of the camera-eye, as discussed in chapter 1.) What projectors are designed to hide, the flicker effect restores to visibility. It prevents the smooth fusion of frames normally perceived during film projection. Through this rupture in the normal perception of the cinematic image, one can catch a glimpse of the

discontinuous and mechanical processes that underlie the seemingly continuous and natural flow of images on the screen. The projector continues to operate at normal speed, but the rhythm of contrasting frames of color (or black and white) produces an equivalent of the projector's own flicker.

The flicker effect thus depends on a three-stage process involving the film's separate frames, the projector's conversion of those frames into discontinuous impulses of light, and the eye-brain's neural response to that attack of light-impulses. Sharits's artistry lies in his ability to produce visual equivalents of that process itself. This is the basis of his reputation as an analytical filmmaker who, in the words of one critic, "demand[s] that the relationship between screen, image, projector, film, and viewer be considered."[45] Certainly Sharits's flicker films are concerned with the material base and self-referentiality of the medium. But his engagement in the dialectics of eye and camera led him to integrate the medium and the mind's own image-making processes. Sharits frees those processes from cinematic equivalents of the outer world, so that they can create perceptions comparable to the inner world of hallucinations. This is the "temporary assassination of the viewer's normative consciousness" Sharits speaks of.

His flicker films enter the realm of the inner eye by attacking the "retinal screen," but once inside the visual system they lose their violence. In fact, their rhythms of often approximate the alpha rhythms of the brain when it turns off external stimuli to concentrate on its own internal perceptions. Studies of electrical currents in the brain have shown that alpha rhythms (eight to twelve cycles per second) tend to appear even when the eyes close briefly; whereas long and deep meditation is, in Robert Ornstein's phrase, "a high-alpha state."[46] Using an electroencephalograph, Small and Anderson found "considerable alpha-like activity" in the brain-wave patterns of subjects watching their film of flickering white circles.[47] Although the projector shows twenty-four frames per second (and in fact each frame is flashed on the screen two or three times), the perceived light impulses may be much slower than that, depending on the degree of contrast from frame to frame. Paradoxically, then, flicker's violent attack on the retina can produce quite opposite effects farther along the visual system. As the rhythmical firing of visual cells spreads through the brain it may produce, not epilepsy, nausea, dizziness, or other disagreeable effects, but the internal peace of the "meditational-visionary experience." With flickering light as the link between the mechanics of the cinematic apparatus and the physiology of the visual system, Sharits produced versions of the Beyond that are perhaps the most concrete and down-to-earth to be found among films for the inner eye.