PART IV

NEW POLICIES AND NEW DIRECTIONS

The American occupation of Japan had one clear turning point—late 1948, almost exactly halfway between the surrender in 1945 and the signing of the peace treaty in 1951. By 1948 strong pressures were mounting in both the United States and Japan for a policy shift away from reform and punishment and toward Japan's reconstruction and eventual reentry into the world community. The most powerful pressures in the United States stemmed from Japan's weak economic performance. Industrial production was not rising fast enough, the rate of inflation was still high, and the Japanese were showing little initiative in tackling their problems. Worst of all, the burden on the American taxpayer was growing, and complaints were swelling about the large sums of money being spent on a defeated enemy with little sign of useful results. The new under secretary of the army, William H. Draper, Jr., was particularly concerned about the economy-minded Republican Congress. He felt Washington had to push SCAP and the Japanese to do better.

Equally important was a shifting mood in Japan. After three years of chaos and dizzying reforms the people wanted order, calm, and more than a minimum standard of living. They wanted leaders who could stand up to the Americans and set Japan on a new course. Yoshida Shigeru, the old-fashioned conservative, soon made a dramatic comeback with a campaign designed to win more freedom of action for the government and build up the self-respect of the people.

Another strong pressure arose from growing East-West tension. In February 1948 the Soviet Union engineered a communist takeover in Czechoslovakia. In June Soviet military forces in eastern Germany blockaded access by the Western allies to their zones of occupation in Berlin, forcing them to undertake an airlift. On the other side of the world the Chinese Red Army under Mao Zedong swept over northern China in 1948, starting the rout of the Nationalist forces, which retreated to Taiwan in 1949. By the end of 1949 half of Asia, measured in area or in population, was communist. In Central Europe and East Asia rivalry between East and West was intensifying.

The American vision of universal peace and Wilsonian internationalism had vanished, to be replaced by what the eminent journalist Walter Lippmann called the "cold war." Pax Americana would no longer operate smoothly in a world of peace and cooperation; instead it would struggle in a world of growing rivalry and frequent crisis. A new policy was formulated to cope with this situation: its catchword was "containmeat."

Firmly ensconced "under the eagle's wings" since the surrender, Japan had been almost totally insulated from the winds of change. The. occupation forces and the Japanese alike carried on as if what happened in the outside world was of little importance to them. But Japan could no longer remain isolated. It had to reenter the world.

The main designers of a new strategy for Japan were Draper and George F. Kennan, the State Department's policy planner and the formulator of the containment concept. Draper's goal was the economic revival of Japan; Kennan's was its political stability. Both wanted Japan to be able to stand on its own feet after a peace settlement, for which U.S. planning was already under way. Neither intended that Japan be an active participant in the cold war or a military ally of the United States. Initially they sought to redefine U.S. policy for Japan and develop a program for economic stabilization and growth. Draper's economic plan meshed with that of the SCAP experts in Japan, and Joseph Dodge, a Detroit banker, went to Japan to push it through.

Along with this revised policy came renewed authority in Washington. Reelected in November 1948, Harry Truman named Dean Acheson secretary of state. They were in agreement that the policies of containment already initiated by the Truman Doctrine for assistance to Greece and Turkey and by the Marshall Plan for the recovery of Europe should be expanded. Among other steps, they wanted to build "situations of strength" in key areas of the world as barriers against commu-

nist encroachment. The economic revival of Japan had taken on new urgency in the wake of the collapse of Nationalist China.

Under the confident hand of Douglas MacArthur, Japan had posed few problems for Washington, but by 1948 it had become the object of attention and concern. Washington wanted a healthier and stronger Japan than MacArthur had been able to produce. Deference continued to be paid to the general's authority and prestige, but the voice of Washington now counted for much more than before. MacArthur knew he could not ignore it.

Chapter 14

Washington Intervenes Draper and Kennan

U.S. economic planning for postwar Japan was a multifarious collection of generally worded reforms, punitive measures, and a firm disclaimer of any obligation to help the Japanese feed themselves and rebuild their country. These policies were carried out by a commander and senior staff with little experience in economic matters. It was characteristic of MacArthur, as his entire career showed, that he did not shrink from responsibility and did not feel entirely tied down by Washington orders. Soon after the occupation began, he was asking for food and raw materials to enable Japan to escape starvation and stagnation. Washington went along. In the first year after the surrender the United States provided Japan with a little more than $100 million in food, fertilizer, petroleum products, and medical supplies, financed by military appropriations.[1]

By 1947 Washington wanted more action by SCAP and better performance by Japan. In a speech on May 8, 1947, Dean Acheson proposed that Germany and Japan be converted into the "workshops" of Europe and Asia, foreshadowing Secretary of State Marshall's momentous speech at Harvard only a few weeks later launching the European recovery program.[2] On August 30, 1947, the newly reorganized Defense Department in Washington filled the new position of under secretary of the Army by appointing General Draper, a dynamic man with broad business and military experience. Washington wanted to build up SCAP's economic staff as well but could not figure out how to overcome MacArthur's well-known resistance to having top posts on his staff

filled by people he did not know and trust.[3] He was particularly averse to Wall Street bankers. As it happened, Draper and the new secretary of defense, James V. Forrestal, were both senior members of the New York investment firm of Dillon, Read.

One of Draper's main tasks was to supervise Defense Department management of areas occupied by U.S. forces after World War II, in particular Germany and Japan. He had served for two years on the staff of General Lucius D. Clay, the military governor of the U.S. zone in Germany, but he knew little about Japan. So Draper decided to go there in September 1947. He met with General MacArthur, his staff, and a number of Japanese including Prime Minister Katayama. Draper was impressed that "the Japanese are cooperating to an unbelievable extent with the occupation," but he got a negative picture of the economic situation. He was disturbed, as he had been in Germany, by the huge costs of the occupation and by the campaigns to break up large business concentrations.[4]

His visit to Japan came at a time when the SCAP anticartel program was going strong. The man in charge, Edward C. Welsh, was a trained economist hired to expedite the program. Welsh arrived in Tokyo in March 1947 and became one of SCAP's most zealous operators, immediately seeing that he would lose influence to GS if he did not move fast on the cartel issue. One of his first actions was to push for dissolution of the two huge trading companies, Mitsubishi Shoji and Mitsui Bussan, which had handled much of Japan's prewar export and import business. Bussan was split into 170 companies and Shoji into 120. No persuasive reason was ever advanced for the breakup of these companies, except, of course, that they were the trading agents for the far-flung enterprises of these two conglomerates. It seemed irrational to destroy them at a time when SCAP had allowed foreign traders to enter Japan and was trying to revive Japan's trade despite the resistance of many of the Allied nations. (The two companies were recombined soon after the end of the occupation. By 1985 they were the second and third largest non-U.S. companies in the world.)[5]

Draper readily perceived that staff officers directed economic operations in Tokyo and that MacArthur and his economic chief, Marquat, provided little input. Draper was not an archconservative or a Wall Streeter looking for capitalist opportunities, but he was an investment banker who carefully studied balance sheets and speedily detected financial trouble. He clearly saw that Japan's productive potential was hobbled by SCAP restrictions and red tape as well as by high inflation.

By the time he returned to Washington, Draper had formulated a broad plan of action. He wanted a policy statement stressing the importance of economic recovery as a U.S. objective. Getting such a statement was easy, despite objections in the State Department that existing policy was adequate. On January 22, 1948, the new State-Army-Navy-Air Coordinating Committee (SANACC, renamed to include the new U.S. Air Force) approved a weasel-worded statement that the supreme commander "should take all possible and necessary steps consistent with the basic policies of the occupation to bring about the early revival of the Japanese economy on a peaceful, self-supporting basis." Secretary of the Army Royall heralded the new American approach in a speech on January 6, 1948: "There has arisen an inevitable area of conflict between the original concept of broad demilitarization and the new purpose of building a self-supporting nation." He clearly implied that the latter purpose had become number one for the United States.[6] Royall's speech was one of the first signs of a new direction in U.S. policy.

The next step was a specific plan. In 1947 Washington and Tokyo were working on plans that turned out to be similar. Draper carried to Tokyo a State Department plan called Crank Up that aimed at a self-supporting Japan by 1950. SCAP's "green book" planned that the United States would provide $1.2 billion in assistance, Japan would become self-supporting in four years, and by 1953 it would be able to export $1.5 billion worth of goods and services. By 1947 U.S. aid was running at about $400 million a year and was even higher for the next two years. All these plans became outmoded when the Korean War broke out in 1950.[7]

To implement his economic strategy Draper targeted two occupation programs for reduction or elimination—reparations and deconcentration of big business—even though the State Department remained opposed to any changes. Reparations, however, were a crucial issue in the FEC, where "more time was given ... to Japanese reparations and related topics than to any other subject which came before the commission."[8] Draper was more impressed, however, by the potent argument that the American taxpayer would eventually pay for any reparations deliveries because whatever Japan shipped out as reparations would delay its recovery and lengthen its period of dependence on the United States for assistance.

One of Draper's clever devices was to commission a group of influential businessmen to study a problem, make sure they knew his view-

point and were generally sympathetic, and then use their report to justify a shift in policy. This was the way he worked out the reparations matter. First came the Overseas Consultants, Inc., under engineer Clifford Strike, which made two surveys in 1947 and recommended huge reductions in the industrial facilities listed by the Pauley report of 1946. Asked for his views on the Strike report, MacArthur asserted on March 21, 1948, that the "decision should be made now to abandon entirely the thought of further reparations.... In war booty Japan has already paid over fifty billion dollars by virtue of her lost properties in Manchuria, Korea, North China and the outer islands.... Except for actual war facilities, there is a critical need in Japan for every tool, every factory, and practically every industrial installation which she now has."[9]

As his second step in the attack on reparations, Draper organized and participated in another study two months later by a group led by Percy Johnston, the chairman of the Chemical Bank and Trust Company of New York. After a three-week stay in Japan, the Johnston committee recommended far larger reductions than those of the Strike committee. Strike had recommended a 33 percent cut in the Pauley proposals, and Johnston recommended a cut of more than 50 percent in the Strike plan. Altogether, reparations would be 25 percent of the 1945 plan.[10] The new approach was the kind that Draper and MacArthur wanted. The State Department questioned the extent of damage that would be done to Japan's economy by the earlier reparations proposals and argued that the SCAP-Army position would be unacceptable to the FEC nations.

On July 25, 1948, MacArthur cabled Washington that Japan would need to retain much of its industrial capacity: "Indications are now that Japanese export trade of the future will have a substantially different pattern than prewar. With the rapid expansion of the cotton textile industry in other countries in the Far East ... it is indicated that future Japanese exports will consist much more of machinery, other capital goods and chemicals, and much less proportionately of textile products than prewar. This ... will require a larger steel and machinery capacity to support export industries with no change involved in the internal domestic standard of living."[11]

The coup de grace to the Allied reparations program came in 1949. On May 6 the United States decided, in NSC-13/3, that the advance transfer program should be terminated and that the FEC should be, advised that all industrial facilities, including ."primary war facilities" stripped of their military characteristics, should be used as necessary for the recovery program. Many factories used for war production in

World War II were later sold to private companies for peaceful production; industrial equipment designed solely for. military purposes was later destroyed by SCAP pursuant to a FEC policy decision of October 30, 1947. On May 12, 1949, the United States rescinded the advance reparations transfer directive to MacArthur and so informed the FEC.[12]

The U.S. action fueled resentment in several Asian countries, notably the Philippines and the ROC, that American policy favored Japan at their expense. This claim had much to justify it, though the American rejoinder that transplanted factories and equipment were rarely usable in backward countries was about equally true. Several points are significant: if the Allies had reached quick agreement on reparations and early deliveries had been carried out by Japanese technicians under Allied supervision, the program might have been beneficial to Asian nations. In fact, however, the Allies probably took too little from Japan after World War II and took too much from Germany after-World War I.

Some critics of American policy claim that reparations were another example of a U.S. policy reversal. It did indeed reverse its position because the U.S. government decided, not without reason, that if Allied agreement could not be achieved in three and one-half years, the policy should be given up. This made all the more sense because reparations were not a reform but a punitive policy that held out little promise of assistance to the Allies.

Draper's campaign to wind up the deconcentration program proceeded more easily and quickly than the struggle over reparations. The main battle, breaking up the zaibatsu holding companies, had long since been completed, but the program to dissolve a large number of big business groupings was just getting started. MacArthur, however, began to have some doubts. Reportedly, he thought it "sounded crazy" to designate 325 companies as excessive concentrations two and one-half years after the antizaibatsu campaign began. Accordingly, he suggested to Washington in January 1948 that an impartial board of American businessmen come to Tokyo to review the deconcentration program. Draper soon put together a group of five men in whom he had confidence. The Deconcentration Review Board arrived in Japan in May 1948. By then some 150 companies had been removed from the original list of 325. The board steadily pared the list during the year of its operation, though it was careful to save SCAP face when it announced in September "there has been no change whatsoever" in SCAP deconcentration policy.[13]

While the board was swinging into action, Draper busied himself

with redirecting deconcentration policy. The first step was to end consideration of FEC-230. After another protracted battle between State and Army, the U.S. representative to the FEC was authorized to state on December 9, 1948: "There is no need to lay down policies for the guidance of the Supreme Commander with respect to any remaining significant aspect of the program Hence, the United States has withdrawn its support of FEC-230 The major points of procedure set out in that document already had been implemented in Japan." General McCoy noted in his statement to the FEC that "the assets of fifty-six persons who comprised the ten major zaibatsu families and the assets of the eighty-three holding companies controlled by these persons have been acquired by the government and are in process of being sold to the Japanese public."[14]

Of the original 325 companies, 297 had been exempted when the Deconcentration Review Board dissolved on August 3, 1949, orders for reorganization of 11 others had been issued, and the remaining 17 cases were in the final stage of processing. The SCAP deconcentration program actually split up only 18 companies, including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Mitsubishi Mining, Mitsui Mining, Toshiba, Hitachi, Oji Paper, and Japan Steel, which was split into Yawata Steel and Fuji Steel.[15]

Japan's biggest banks did not fall under the 1947 Law for Elimination of Excessive Concentrations of Economic Power. These banks, including Dai Ichi, Chiyoda (a cover name for Mitsubishi), Fuji (cover for Mitsui), Osaka, and Sanwa, played a key role along with a number of new banks in Japan's economic revival after the occupation. Thirty-six years after the occupation ended, the ten biggest banks in the world were Japanese.[16]

MacArthur told Patrick Shaw of Australia in April 1949 that the Draper mission was "the most high-powered effort of big business interests to break down his policy of preserving Japan from carpetbaggers." The Canadian representative, Herbert Norman, had commented earlier, "On more than one occasion I have noticed General MacArthur's addiction to the vocabulary of the trust-busting era; thus his determination to break up the zaibatsu in Japan is a genuine part of his political philosophy." A Japanese business leader said later that "zaibatsu dissolution was a major factor in Japan's postwar growth." It also helped bring about a managerial revolution in which stockholding was widely dispersed, managers ran companies, and in most industries competition was keen.[17]

Draper's campaign to make economic recovery the top priority of the occupation was the first serious intrusion by Washington into MacArthur's autonomy in Tokyo. Soon after came a statement of national policy that provided a broad framework for the new approach. Approved by President Truman on October 9, 1948, this document was one of the early products of the National Security Council (NSC) and became well known as NSC 13/2.[18]

NSC 13/2 was primarily the brainchild of George F. Kennan, who at age forty-three was regarded as America's foremost authority on policy toward the Soviet Union. His article in the July 1947 issue of Foreign Affairs on the sources of Soviet conduct had won wide acceptance as a perceptive and realistic prescription for the United States and its friends to follow in dealing with the communist nations. His analysis became an essential element in U.S. foreign policy and was universally known as containment, a description he did not entirely appreciate and the meaning of which was hotly debated.

Secretary of State Marshall appointed Kennan the head of a new policy planning staff in 1947. After completing a study on European recovery that was valuable in the formulation of the Marshall Plan, Kennan and his staff decided to look at Japan. The immediate issue they faced in the late summer of 1947 was whether to go along with plans for a peace conference, for which Far Eastern experts in the State Department had made extensive preparations. The basic point, in Kennan's view, was to determine whether Japan was stable and strong enough to stand on its own feet; he was convinced that the restoration of a postwar balance of power required that Western Europe and Japan stay out of communist hands.[19]

Kennan had had no experience in the Far East. Concerned that U.S. policy in Japan might have the effect of "rendering Japanese society vulnerable to Communist political pressures and paving the way for a Communist takeover," he suggested that someone go to Japan to talk to MacArthur and examine the situation there firsthand. Kennan sensed that relations between Marshall and MacArthur were "not cordial" and that the secretary of state was "reluctant to involve himself personally in any attempt to exchange views with General MacArthur." No one in the State Department seemed to want this job, and the task soon fell to Kennan.[20]

He was the most important State Department official to visit Japan during the occupation. In the same period high officials went regularly to Europe; Secretary of State Dean Acheson, for example, made eleven

trips between 1949 and 1952. Although State Department officials complained that their views did not get much hearing in Japan, they shrank from any direct tilt with MacArthur. MacArthur's military associates in the Pentagon had many of the same problems with the general, and Kennan thought they probably relished "watching a civilian David prepare to call on this military Goliat.".[21]

Kennan arrived in Tokyo at the end of February 1948. His detailed reports of his three meetings with MacArthur are among the rare records of MacArthur's views that can be called complete and candid. After an uncertain start, Kennan and the general got along surprisingly well. At their first meeting, a luncheon on March 1, the general held forth in a virtual monologue, a "MacArthur sermon," about the prospects for democracy and Christianity in Japan. "Overcome by weariness," Kennan says, he had little to offer at this meeting.[22]

In advance of the second meeting, Kennan sent the general a note, which reflected his own thoughts, suggesting that the emphasis of occupation policy should be threefold: the "maximum stability of Japanese society" based on a "firm U.S. security policy," an "intensive program of economic recovery," and a "relaxation in occupational control designed to stimulate a greater sense of direct responsibility" in the Japanese.[23]

At the meeting of March 5 MacArthur responded at length. Regarding security, he asserted that the strategic boundary of the United States ran along the island areas off the eastern shore of the Asiatic continent and that Okinawa was "the most advanced and vital point in this structure," which the United States had to control completely. MacArthur further noted that it would not be feasible for the United States to retain bases in Japan after a peace treaty because other Allied nations would then have a right to do likewise. Regarding economic recovery, the general agreed that it should be made a primary policy goal. He was already doing all he could to achieve this, he said, but the difficulty was in the development of foreign trade, and in this matter the FEC nations were "shamelessly selfish and negative" toward Japan.[24]

Regarding a relaxation of control, MacArthur asserted that occupation controls were not so stringent as many in the United States thought. The general went on to describe some of the reform measures. Provisions in the new constitution renouncing war had resulted from a Japanese initiative. The zaibatsu were not men of superior competence; the real brains of prewar Japan were in its armed forces. Most reform measures had been completed, civil service reform being the only im-

portant one remaining. MacArthur said he was planning to cut down the SCAP section most concerned with subjects of interest to "academic theorizers of a left-wing variety," commenting that he had a few of these in his shop but did not think they did much harm.[25]

Changing the subject, Kennan suggested that the FEC, which MacArthur had indicated would be an obstacle to any attempt to change occupation policy, had largely fulfilled its main function and could be "permitted to languish." The general thought this was the right line to take and said he could easily certify to the FEC within a short time that the surrender terms had been carried out. Kennan summarized by saying the position should be that "the occupation is continued, not for the enforcement ... of the terms of surrender, but to bridge the hiatus in the status of Japan caused by the failure of the Allies to agree on a treaty of peace."[26]

At the third meeting, on March 21, Draper took part and mentioned that some planners in the Department of the Army thought Japan should have a "small defensive force." MacArthur prefaced his reply by urging that the United States press for an early peace conference, suggesting that if a treaty could be negotiated, the Soviets would eventually go along with it. He then asserted that he was "unalterably opposed" to a Japanese military force because it would violate fundamental SCAP policies and alienate Far Eastern nations. A rearmed Japan would have trouble surviving economically and could never be more than a fifth-rate military power, "a tempting morsel, to be gobbled up by Soviet Russia at her pleasure." In addition, the Japanese had sincerely renounced war and would be unwilling to establish an armed force.[27]

While in Japan, Kennan formed strong and skeptical views on some occupation policies. Speaking of the purge program, he commented later, "The indiscriminate purging of whole categories of officials, aside from the sickening resemblance to the concepts of certain totalitarian governments, was a denial of the civil rights provisions of the new Japanese constitution and created an unfortunate setting for the promulgation of Japan's new legal codes." The anticartel program was in his eyes the work of people who saw problems "exclusively from the standpoint of economic theory and whose enthusiasm and singleness of purpose have sufficed to get them documented as U.S. government policy." He thought war crimes trials "were profoundly misconceived." The "hocus-pocus of a judicial procedure" belied the fact "they were political trials." Echoing Winston Churchill, Kennan asserted it would have been better "if we had shot these people out of hand at the time of the

surrender." As for reparations, he said, echoing MacArthur, it was "sheer nonsense ... and basically inconsistent with the requirements of Japanese recovery" to transfer industrial equipment from Japan to other Far Eastern countries. He was also somewhat appalled by the lifestyle of American occupationaires, commenting that "it is instructive rather than gratifying to get a glimpse of this vast oriental world, so far from any hope of adjustment to the requirements of an orderly and humane civilization, and to note the peculiarly cynical and grasping side of its own nature which Western civilization seems to present to these billions of oriental eyes, so curious, so observant, and so pathetically expectant."[28]

After three weeks in the Far East, including a short inspection trip to the Philippines, Kennan returned to Washington. Within a few days, his report to the NSC was ready. It began with a caveat that the United States should not press for a peace treaty. He explained later that "in no respect was Japan at that time in a position to shoulder and to bear successfully the responsibilities of independence that could be expected to flow at once from a treaty of peace." This was not, of course, the view of General MacArthur.[29]

The report offered twenty important policy prescriptions. Next to its security interests, the United States should make economic recovery its primary goal, stressing to the Japanese the need to increase production and exports. Kennan's proposals regarding political reform were more controversial: SCAP should undertake no new reforms and should relax pressures on those already in effect, intervening only if the Japanese sought to revoke or compromise fundamental reforms. The control system under SCAP should be maintained, but more responsibility should be given to the Japanese government. The report gave a lot of attention to Okinawa and went along with MacArthur: the United States should "make up its mind at this point that it intends to retain permanently the facilities at Okinawa."[30]

Kennan was most concerned about the weak power of the police, which had been broken up into many small units that lacked central direction, a central pool of information, and any means of coordination between the national rural police and the local police. Police officers were armed mostly with pistols, with only one for every four men. In Kennan's words, "It was difficult to imagine a setup more favorable and inviting from the standpoint of the prospects for a communist takeover." He cited as an example of his concern that police in Tokyo had no records of lawless elements in Osaka, such as dissident Koreans.

In his report Kennan recommended that the police be strengthened by better equipment, creation of a coast guard, and establishment of a central organization along the lines of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He did not recommend any increase in the size of the police forces, and he made no recommendations regarding a military force, but he did talk with Draper about the possibility of "a strong, centrally-directed, National Rural Police." Kennan also thought the SCAP purge categories had been too rigid and should be reviewed to permit some exceptions.[31]

On another knotty issue, a greater civilian role in the occupation, Kennan partly disagreed with MacArthur, recommending that the State Department send a permanent political representative to Japan. Even this modest compromise fell by the wayside as his report made its way upward through the U.S. government, as did an ambitious scheme by some in the State Department to assume control of all nonmilitary activities in Japan. MacArthur was adamant in his opposition. He liked being supreme. There was little talk after 1948 of any change in the structure of the occupation.

Kennan proposed other ways to bring about a more normal relation with Japan. Cultural interchange between Japan and the United States should be strongly encouraged. Precensorship of the press should cease. The impact of the large American military community in Japan should be mitigated, and the costs of the occupation paid by the Japanese government should be reduced. FEC and ACJ controls over Japan could continue but should not be strengthened.

Kennan's report found wide acceptance in Washington, sailing through the bureaucracy with only minor changes. The consensus reflected a general belief that the occupation had achieved its basic purposes of disarming Japan and laying a foundation for democratic government. In this sense, the occupation was over. In Europe the United States and its Allies had by 1946 veered sharply away from reform and punishment and toward economic recovery. By 1948 they were preparing to turn over most of their control in the western zones to a new German government. They might have liked to do the same in Japan, but the thought of dumping both MacArthur and the FEC made this option uninviting.

The general had a few comments on the Kennan report. Many were minor: U.S. occupation forces in Japan could not safely be reduced; occupation costs were not a heavy burden on the Japanese economy because they were devoted largely to construction of buildings, which

would be useful for the Japanese in the future; reducing the influence of the FEC and the ACJ was desirable; and war crimes trials could not be expedited. On a few points, however, he felt strongly. Any "expansion" of the police force would bring "explosive international reactions" in the FEC. He refused to alter purge policy, pointing out that it bore the approval of the FEC and that even though his execution of the policy had been "as mild as action of this sort conceivably could be," he had been bitterly attacked by five of the Allied nations for his "excessive mildness."[32]

Some of MacArthur's views resulted in modifications of the Kennan proposals. But the provisions regarding the police and the purge were retained much as originally drafted. These led to acerbic exchanges between Washington and Tokyo after the president approved the report on October 9, 1948. The State Department wanted to press MacArthur hard to carry out the provisions of NSC 13/2, and the Department of the Army went along reluctantly after watering down the wording of the messages to Tokyo.[33]

One stratagem was to send these instructions to MacArthur as U.S. commander in chief in the Far East (CINCFE) rather than as supreme commander for the Allied powers. MacArthur quickly rejoined that he had been designated an Allied commander by the Moscow agreement of 1945. Were the United States to breach this agreement by unilaterally sending him orders, other Allied powers might try to do the same. The Soviets might claim this right, "and with the present emasculated condition of our occupation force it is doubtful that we could successfully resist any thrust [they] might decide upon against Hokkaido or any other part of Japan." MacArthur added the telling comment that "NSC 13/2 has not been conveyed as an order to SCAP by appropriate directive prescribed by international agreement and therefore SCAP is not responsible in any way for its implementation."[34] These hard-hitting messages, which were drafted by Whitney, smacked of insubordination. They did not deter State and Army. These departments knew, as did MacArthur, that the occupation was a U.S. show, and they were determined that American policy would prevail. On February 15, 1949, Washington informed Tokyo that several sections of the basic directive of November 3, 1945, regarding the purge had been rescinded, as had the important provision that the supreme commander should take no responsibility for the economic rehabilitation of Japan. These policy adjustments had little impact on MacArthur, who had decided three years earlier to ignore the injunction against economic help for Japan.

On May 2, 1949, the State Department made an internal report on the implementation of NSC 13/2, six months after the president approved it. The internal report gave MacArthur low marks for his performance: no action had been taken to reduce the psychological impact of the occupation, no specific steps had been taken to prepare long-term plans for Okinawa or to improve the facilities there, and Japanese police had been issued more pistols, but nothing had been done to set up a national investigation bureau or to increase coordination of police operations around the country.[35] Nor had there been any reduction of SCAP's supervisory role over the Japanese government. In fact, SCAP had stated that greater stress on economic recovery had "completely reversed this policy." The purge had not been modified. Occupation costs had not been reduced. Only two actions were being taken to carry out the policy: intensive efforts were being devoted to economic recovery, and precensorship of the press had been terminated.

As he often did, MacArthur decided to implement the policy his own way without acknowledging Washington's role. On May 6, 1949, he ordered all headquarters sections to review outstanding directives and procedures for the purpose of relaxing controls and stimulating a sense of self-reliance and responsibility among the Japanese. Without mentioning the NSC policy paper, MacArthur based his order on his own press statement of May 2, 1949, on the second anniversary of the Japanese constitution, in which he proclaimed, "In these two years the character of the occupation has gradually changed from the stern rigidity of a military operation to the friendly guidance of a protective force. While insisting upon the firm adherence to the course delineated by existing Allied policy and directive, it is my purpose to continue to advance this transition."[36]

One of MacArthur's senior staff officers later described this program as "little more than window-dressing." But he did point out that SCAP took a number of actions under this order to reduce its operations and interventions in Japanese activities. In particular, it reduced the civilian employee element of the occupation from 3,660 to 1,950. It removed civil affairs teams—formerly known as military government teams— from prefectural capitals and cut their personnel drastically from 2,758 to 526.[37] Moreover, SCAP continued to give the police more pistols and training. The Japanese government was permitted to establish an appeals board to review purge cases, although its jurisdiction was restricted.

A number of American and Japanese historians have labeled Kennan

the master planner of a new policy of reverse course designed to implicate Japan in cold war politics. Kennan would have denied that his proposals were designed to turn back the clock on reform, although he did say later he could understand how younger scholars might feel he had taken a stern attitude regarding U.S. policy toward Japan. He believed that the reforms should be retained, some in modified form, and that the time had come for the Japanese to implement the reforms their way so long as they did not try to undo them. Nor would he have understood the argument that his policies were intended to embroil Japan in the U.S. rivalry with the Soviet Union.

Kennan's goal was to help Japan build adequate political stability and economic strength to make its way after negotiation of a peace treaty, which was already an active item on the Allied agenda. He felt Japan had to have better protection against internal threats to its security, especially a more effective police force, and he was willing to sanction firm but legal measures to control communists and left-wingers. Kennan did think a number of occupation reforms went too far, but he made no effort to change them. Nor did he take part in any group lobbying for change.

Consistent with his view that containment was a political, not a military, policy he made no recommendation that Japan should develop military forces or even that the United States should station forces in Japan after the peace treaty. He said in his Memoirs that "it was my hope—shared at the moment, I believe, by General MacArthur—that we would eventually be able to arrive at some understanding with the Russians, relating to the security of the northwestern Pacific area, which would make this unnecessary."[38] These were hardly cold war polemics.

Kennan left himself a loophole on the crucial issue of rearmament. Two days after meeting MacArthur, he inserted an explanatory note in his report that said in part that because of the Soviet threat and Japan's internal weakness (he considered Japan much more vulnerable to communist pressure than MacArthur did), Japan could not be left defenseless after a peace treaty; either there should be no treaty, or "we must permit Japan to rearm to the extent that it would no longer constitute an open invitation to military aggression." He added that if the USSR's military-political potential became less threatening in the future, then a treaty of demilitarization with Japan would be feasible.[39]

Kennan wrote later that his efforts in 1948 made "a major contribution to the change in occupational policy that was carried out in late 1948 and 1949; and I consider my part in bringing about this change to

have been, after the Marshall Plan, the most significant constructive contribution I was ever able to make in government. On no other occasion, with that one exception, did I ever make recommendations of such scope and import; and on no other occasion did my recommendations meet with such wide, indeed almost complete, acceptance."[40]

Kennan was not optimistic about the situation. In a talk he gave at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in October 1949, he said that Japan would have to make a "drastic adjustment" after the occupation and would face a "dangerous situation" in Asia because the country had been demilitarized. He felt there was a likelihood of reversion to an "extreme form of nationalism" and to a "totalitarian government," which did not bode well for the United States.[41]

The State and Defense departments did accept and apply the proposals in NSC 13/2, but MacArthur all but shunned them. They did not circulate in SCAP headquarters as new policy for the conduct of the occupation. MacArthur did not mention Kennan or NSC 13/2 in his Reminiscences . Yet he understood that Washington had decided on a shift in course. In a remark to Sebald on August 15, 1949, MacArthur said he was implementing the NSC policy as rapidly as possible, thus preparing Japan for eventual return of sovereignty.[42] And the new Japanese government, without knowing the bureaucratic tangle inside the U.S. government, welcomed the revised U.S. approach, which soon became evident despite MacArthur's shunning.

1.

Autographed photograph of General Douglas MacArthur and Emperor

Hirohito at their first meeting, September 27, 1945. Courtesy of MacArthur

Memorial Archives, Norfolk, Virginia.

2.

Aerial photograph of Hiroshima (taken December 22, 1945). Note the

church in the foreground. Courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, D.C.

3.

MacArthur relaxing. Courtesy of the Thames Collection.

4.

MacArthur greeting John Foster Dulles on his first trip to Japan, June 21,

1950. Ambassador W. J. Sebald is at right. Courtesy of the National Archives,

Washington, D.C.

5.

Dulles, Sebald, and Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru in conversation at a

reception in Tokyo, January 21, 1951. Courtesy of the National Archives,

Washington, D.C.

6.

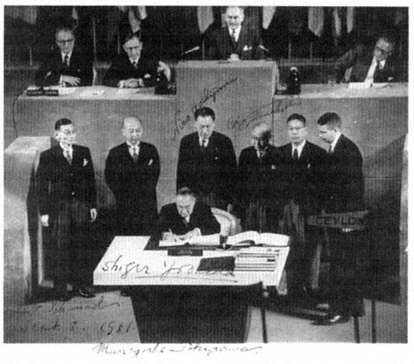

Prime Minister Yoshida signing the peace treaty, as his co-signers—

Ichimada Hisato of the Bank of Japan, Tokugawa Muneyoshi of the House of

Councillors, Hoshijima Nito and Tomabechi Gizo of the House of Representa-

tives, and Finance Minister Ikeda Hayato—look on. Secretary of State Dean

Acheson sits in the middle behind them. Courtesy of MacArthur Memorial Ar-

chives, Norfolk, Virginia.

7.

Prime Minister Yoshida signing the security treaty on September 8, 1951, at

the San Francisco Presidio. Looking on are Dulles, Secretary of State Dean

Acheson, and Senator H. Styles Bridges, ranking minority member of the Senate

Armed Services Committee. Courtesy of the National Archives, Washington,

D.C.

8.

Yoshida's calligraphy. Yoshida Shigeru was well known for his calligraphy.

He penned this quotation from the opening chapter of the Analects of Con-

fucius in 1955 as a gift to the new International House in Tokyo, where it is

now displayed. It means "Is it not delightful to have friends coming from distant

quarters?" (Legge's translation). Courtesy of International House, Tokyo.

9.

Two old friends. MacArthur and Yoshida meet at the Waldorf-Astoria on

November 5, 1954. Courtesy of Wide World Photos.

10.

Yoshida in retirement at Oiso. Courtesy of Asahi shimbun.

Photograph by Yoshioka Senzo.

Chapter 15

New Life in Tokyo

Yoshida and Dodge

October 9, 1948, the day President Truman approved Kennan's new policy, was far more significant in the modern history of Japan for another reason. On that day, Yoshida Shigeru met with MacArthur and told the general he planned to be a candidate for the prime ministership. Within a week Yoshida succeeded in capturing the prize and thereby inaugurated a long-lasting rule of Japan by moderate conservatives.

Yoshida found the road back to the top of the political heap a rocky one. But he was spunky and determined when the crisis began in early October, despite an attack of gallstones.[1] In an effort to head off Yoshida, SCAP tried to enlist two other prospects for the job, one supported by MacArthur and Whitney and the other by their powerful subordinates in GS, Charles Kades and Justin Williams. Williams approached Yamazaki Takeshi, the secretary general of Yoshida's own party and a man with wide political experience and a liberal outlook. GS's firm support for Yamazaki and opposition to Yoshida opened up divisions in party ranks. Some of the old guard began to talk about getting rid of the party leader, who had failed once and was not strong enough to keep all his lieutenants in line.[2]

Yoshida remained spirited and steadfast. On October 7 he lectured his colleagues that party decisions should be made on the basis of democratic procedures that would set a good example for the nation, not on the basis of personal likes and dislikes. Yamazaki's attempt to oust Yoshida had sparked his ire, and he declared, "If General MacArthur

forces this on me, I will obey.... I will go to him and find out for myself."[3]

Yoshida and MacArthur met alone on October 9. Neither made a record of the meeting. Yoshida later used various terms to describe the general's attitude toward his candidacy, varying from "understanding and encouragement" to "approval" to "I want you to do it." All of these implied MacArthur's support and reinforced the prime minister's decision to run. To be the sole Japanese source of information on MacArthur's views was a powerful weapon in Yoshida's hands, which he used often and effectively.[4]

Right after seeing Yoshida, MacArthur had a lengthy meeting with Miki Takeo, the head of the People's Cooperative Party, who had served in the Diet without a break since 1937. Miki was then forty-one, which was young for a Japanese politician; his political position was middle of the road; and he had studied for two years at the University of California at Berkeley. According to Miki's account, General Whitney had earlier conveyed "General MacArthur's request that I succeed Dr. Ashida as prime minister." On October 9 MacArthur "personally reiterated the request that I become the next premier." Miki later commented that "under the circumstances where General MacArthur was the virtual ruler of Japan, if I had acceded to the General's wish, I could have gained the post of prime minister."[5]

Miki went on, "Nonetheless I refused the offer. The line of reasoning I presented to the general for refusing his most cordial consideration was as follows: (a) I am the leader of a minority party in the Diet, the People's Cooperative Party. (b) For General MacArthur to establish the ground rules for Japan to be ruled by a parliamentary democracy, he must take into consideration the fact that the Liberal Party, headed by Yoshida, held the largest number of seats in the Diet among the opposition parties and that his governance of Japan would proceed more smoothly with Yoshida installed as premier, since that would accord with the democratic requirements of the nation at the time." Miki thus bowed out, and MacArthur did not press him. Miki did become prime minister twenty-six years later, when he succeeded the scandal-covered Tanaka Kakuei in 1974.

This was a curious episode. As Miki said, MacArthur was "the virtual ruler of Japan" at the time. He could have forced the selection of Miki or the rejection of Yoshida. Yet the general generally tried to avoid getting involved in the selection of Japan's political leaders. His

tentative overture to Miki, which the evidence clearly shows he made, was the farthest he ever went in intervening in what he considered a Japanese process. Surprisingly, no word leaked out at the time about what Miki and MacArthur had discussed, despite intense curiosity in political circles. It was, of course, even more surprising that MacArthur and Whitney were going one way while two of their senior staff officers were going another.

Yoshida's political strategy worked well. He had argued skillfully against "plot politics" at a time when many Japanese politicians were disturbed by GS's interference in their affairs. And MacArthur's apparent endorsement was no doubt decisive. Yamazaki was talked out of making a challenge, and he soon resigned his seat in the lower house. Williams wrote a memo offering a psycho-historical explanation: "Yamazaki's action is strictly in keeping with the tenets of bushido , which require that a samurai commit harakiri if he causes his lord and master any embarrassment. That Secretary General Yamazaki has caused his feudal lord, President Yoshida, considerable embarrassment during the last several days, there is no doubt. In fact, the immediate threat of overthrowing and replacing his feudal lord is so imminent that the Democratic Liberal Party has coerced him into accepting the most drastic fate of all, political suicide."[6] Actually, Yamazaki was reelected in January 1949 and had a long and successful career thereafter in the Democratic Liberal Party.

The British ambassador saw MacArthur on October 16 and reported to London that the general "showed little pleasure" at Yoshida's nomination but "stressed that this was, of course, entirely a matter for the Japanese and that he had not interfered in any way in the recent political crisis ."[7] Sir Alvary's version rings truer than Yoshida's account. Clearly, the general had talked to both Miki and Yoshida. MacArthur probably listened to Yoshida explain his intention to stand for the premiership and said something like "good luck," as he had said to Yoshida in May 1946. This would have been all Yoshida needed to pass the word to his cohorts—and to the opposition—that MacArthur had "encouraged" him to seek the top job. MacArthur stretched the truth when he said he had not interfered in any way in the recent crisis, but Yoshida stretched it more when he let on that he had been supported by MacArthur.[8]

On October 14 the House of Representatives elected Yoshida prime minister by a vote of 185 to 1 with 213 blank votes cast. At a press conference soon after the vote, Yoshida expressed regret for the recent

"troubles" but stressed his goal of national reconstruction and appealed for public support. A few days later he let Colonel Bunker, MacArthur's aide, know he wanted to thank MacArthur for his "sympathetic interest and assistance during this period."[9]

Yoshida sensed that public opinion was on his side. The other political parties were not doing well. A huge scandal had engulfed the Ashida cabinet. Difficult economic conditions prevailed throughout the country. And the occupation's meddling in domestic politics was stirring resentment among Japanese politicians. In Williams's words, "It was at this very time that GHQ intervention in Japanese affairs reached unprecedented heights, characterized by SCAP seeming to run afoul of Washington's instructions, the minority party government doing battle with the majority opposition parties, ... Government Section clashing with ESS, and General Whitney tilting with Prime Minister Yoshida."[10] Modesty may have deterred Williams from including the "Yamazaki affair" in his critique.

Yoshida wanted to call an election while his popularity was high and his opponents were in headlong retreat. Although the Democratic Liberal Party was the largest in the House of Representatives, with 153 seats, this figure represented only one-third of the 466 seats. The Socialists and the Democrats with their small party helpers still held a solid majority of 235 seats and could block a vote to dissolve the Diet. It took Yoshida two months of abrasive bargaining with both his political opposition and SCAP before the Diet could be dissolved and an election called.

Yoshida's subservient position became painfully clear when SCAP insisted that amendments to the NPSL be passed before the Diet was dissolved. GS went even further and insisted that the dissolution could take place only after the lower house of the Diet passed a resolution of no confidence in the new cabinet. Yoshida and the Democratic Liberals strongly supported the amendments to the NPSL, having consistently advocated that government workers should not have the right to strike or bargain collectively with the government. Yoshida was not keen on the provision for an independent national personnel authority, another of Blaine Hoover's borrowings from U.S. practice, but this was a detail the prime minister could accept. Hoover complicated the issue by insisting on a pay raise for government workers,[11] which MacArthur supported on the theory that it would mitigate the workers' bitterness over the new restrictions. SCAP's financial experts shuddered at the prospect of additional spending, but they were overruled.

Diet dissolution raised a serious question of constitutional interpretation, one of the few presented in the early years of the constitution's operation. Article 69 provided that the House of Representatives could be dissolved if it passed a resolution of no confidence in the cabinet or rejected a confidence resolution. Article 7 provided that the emperor could dissolve the House of Representatives with the advice and approval of the cabinet. The question was whether the House of Representatives could be dissolved only by a vote pursuant to Article 69 or whether it could also be dissolved under Article 7 by decision of the cabinet or the prime minister alone, with the emperor giving his approval as a mere formality. No one argued that the emperor had the power unilaterally to dissolve the lower house.[12]

To head off the impasse, Williams suggested a solution: the amendments to the NPSL would be enacted, the bills for a pay raise and the supplemental budget would be approved, and then a resolution of no confidence would be presented and passed, with opposition support. This proposal led to the famous "collusive dissolution," which acquired considerable notoriety in Japanese politics. According to the terms of this stratagem, the major parties would all commit themselves in advance to vote for the bills on the legislative agenda, and then the opposition would introduce and vote for a motion of no confidence in the government, which would dissolve the lower house pursuant to Article 69 of the constitution. Yoshida went along reluctantly with this deal, which he felt was not sanctioned by the constitution and violated parliamentary principles.[13]

On November 27 Whitney and Kades called on the prime minister to force the issue. Whitney reported MacArthur's fear that the political situation would seriously worsen if the wage increase were not approved before the Diet was dissolved. Whitney asserted that to go through the emperor for authority to dissolve the Diet would raise grave concern among the Allied powers that an attempt was being made to restore governmental powers to the throne. Yoshida replied that the emperor could dissolve the lower house with the advice and approval of the cabinet. Whitney countered that the emperor's role was a ministerial function to be performed only after the lower house passed, or failed to pass, a motion of no confidence. When the prime minister asked Whitney what should be done next, the general coyly replied that he was not there to suggest but to act as "messenger for General MacArthur."[14]

Yoshida decided to try pinning MacArthur down. And so the next

day, November 28, he wrote the general a letter that began with pointed irony, "General Whitney was kind enough to call on me this morning to give advice on the current political situation. I feel I have to express my sincere appreciation for his valuable assistance at this juncture. May I take the liberty of asking you to convey to General Whitney my feeling of deep gratitude?" The prime minister then summarized his understanding of the agreement and concluded that "General Whitney will see to it that the opposition parties act in good faith in accordance with the line set as above."[15]

Yoshida may have been the head of a government under military occupation, but he was acting more like a negotiator than a subordinate. And he seemed to be putting MacArthur into the role of an arbitrator. The general still wanted to stand aside, for on November 29 Whitney replied that MacArthur had "noted with satisfaction the compromise agreement which had been determined upon by all major political parties." Whitney then informed the prime minister that General MacArthur and General Marquat had decided to leave it to the Japanese government to set the wage level for public servants.[16]

Nevertheless, SCAP officials insisted on higher figures than Yoshida wanted, and he was forced to give in after meeting with MacArthur, Whitney, and Marquat. Yoshida stated in his memoirs that the result was a "defeat" because ESS changed its position. After much scrambling by both occupation and Japanese finance experts to figure out where to get the money for the pay raise, the wage bill and the supplemental budget were approved on December 21 and 22, 1948.[17]

One victim of the budget battle was the minister of finance, Izumiyama Sanroku. At a late meeting of the Diet on December 13, his inhibitions loosened by sake, he made advances toward a woman member of the Democratic Party, reportedly asserting, "I like you better than the supplemental budget." Later he fell asleep on a couch in the Diet lobby. A photograph of the recumbent minister got wide play in the press the next day. He immediately resigned.[18]

In keeping with the plan for a collusive dissolution, a motion of no confidence in the Yoshida cabinet was passed on December 23, and the lower house was dissolved. Yoshida called a new election for January 23, 1949. The sixty-eight days of the second Yoshida cabinet had been stormy, but he was confident of his leadership ability and his good relations with MacArthur. Yoshida sensed, too, that the strong-arm methods of the occupation and the evident animus of GS toward him were stirring some resentment among the Japanese.[19]

Yoshida had been preparing for an election since leaving office nineteen. months before. After putting down the Yamazaki insurrection and finally meeting SCAP conditions for a general election, he was ready. In his campaign he focused on Japan's two main requirements—economic stabilization and an early peace treaty. He also promised tax reductions and called for self-reliance by the Japanese people, with an over-. tone of greater independence and freedom from interference. These ideas turned out to be appealing.

True to his hopes, the election gave Yoshida and the Democratic Liberals an absolute majority of 264 seats, one of the few times in Japanese history that a party won so sweeping a victory. In comparison with the election of 1947, Yoshida's party doubled the number of Diet seats and the percentage of votes it obtained. The Socialists suffered a catastrophic defeat, falling from 143 seats to 49.[20] The Democrats dropped from 90 to 68. The Communist Party, however, skyrocketed from 9 to 35 seats. Thus, the two extremes—the Communists and the Democratic Liberals—profited from the failure of the former coalition parties in the middle. A number of Socialist leaders, including Katayama and Nishio, were defeated. The husband and wife team of Kato Kanju and Kato Shizue, left Socialists of moderation and intelligence, went down.

The day after the election MacArthur issued a remarkably brief and simple statement: "The people of the free world everywhere can take satisfaction in this enthusiastic and orderly Japanese election, which at a critical moment in Asiatic history has given so clear and decisive a mandate for the conservative philosophy of government."[21]

A few days later the indefatigable British ambassador saw MacArthur and Yoshida to get their slant on the election. MacArthur said he was "delighted" that a strong conservative party would be in power for four years. He did not consider the Communists' sharp success, 35 seats and 9.6 percent of the votes cast, as "anything very serious" because he thought they had now "reached their peak in Japan." Nevertheless, he said, "he would watch them `like a hawk'; if they broke the law they would pay for it."[22]

MacArthur commented, "Yoshida was an astute diplomat and he had learned a lot lately regarding the internal politics of his country and the conditions in occupied Japan." Gascoigne told London that the general had changed his opinion of Yoshida, "for in the past he had severely criticized him to me, inter alia, for his efforts to circumvent occupation regulations." Some historians have questioned Yoshida's

ability as a diplomat, but he was winning plaudits from the supreme commander.[23]

Sir Alvary found Prime Minister Yoshida "jubilant" over his victory. He assured the ambassador he would not be too stern with the labor movement. Saying he was a "good liberal," with a horror of the extreme right and the extreme left, Yoshida asserted that he wanted to bring to Japan a moderate, two-party system in which the party of the left would resemble the British Labour Party. The prime minister showed some prescience in observing that communism in Japan had reached its high-water mark; he added that it would never be successful because the people "hated" Russia and "feared" communist ideology.[24]

The big victory of the conservative Democratic Liberals was undoubtedly the most important result of the election, and the jump in Communist representation in the new lower house was the most surprising. These results were readily explained by the dismal failure of the middle-of-the-road parties to give Japan any sense of purpose during their one and one-half years in office.[25] The Democratic Liberal Party became the dominant force in Japanese politics, buttressed by later coalition with the main wing of the Democratic Party and rechristened the Liberal Democratic Party in 1955. The Communists were never able again to reach the high level of votes and seats they had attained in 1949. The Socialists managed to regroup themselves and do better in later elections, but they never became a fully unified party and finally split in 1960.

The principal engineer of these results was Yoshida Shigeru. He had rebuilt his party and taken charge of the conservative movement. He markedly influenced the course of Japanese politics by injecting new blood into the conservative forces. SCAP had expected that its reform programs would develop new and enlightened leaders, particularly among the Social Democrats, but the Socialists proved too weak in doctrine and too divided by factionalism to nurture strong principles and leaders.

Yoshida, however, began in 1949 to bring in from the ranks of the bureaucracy a group of younger men who were to provide some of Japan's best leaders in the years to come. Among them were Ikeda Hayato from the Finance Ministry, Sato Eisaku from the Transportation Ministry, both of whom became highly successful prime ministers, and Okazaki Katsuo from the Foreign Ministry, who became foreign minister in 1952. Fifty-five former bureaucrats were elected to the Diet in 1949, nearly all of them Yoshida supporters. Although most of them

had held positions in government during and before the war, their technical expertise and lack of roots in old-guard politics made them desirable as legislators.[26] Yoshida's program for finding leaders no doubt succeeded because of the openings created by the occupation purges and reform policies, but it was his inspiration that created the "Yoshida school," as the Japanese call it. The program also fortified Yoshida against old-guard politicians and purgees when they made their bid for power several years later.

Yoshida felt so strong after the election that following lengthy discussions with the political adviser, he was willing to sign a one-sided agreement with the United States waiving Japan's claim for the sinking of the merchant ship Awa Maru by a U.S. submarine in April 1945. The sinking occurred after the United States had granted safe conduct to the vessel, which had delivered relief goods to Allied prisoners of war in Southeast Asia and was returning to Japan with two thousand Japanese passengers, all but one of whom were lost.[27]

MacArthur's confidence in the prime minister had risen markedly. Instead of criticizing Yoshida as lazy, as he had done in the past, the general told Herbert Norman, the Canadian representative, on February 11, 1949, that "Yoshida's political philosophy was comparable to that of the Conservatives in England or the Republicans in the United States. Yoshida was free from political ambition, anxious to do the right thing and realized the dangers of abusing the majority respect he now enjoyed in the Diet." MacArthur thought it was wrong to describe Yoshida as reactionary or ultraconservative; "these forces were represented by the zaibatsu and the military and were now eliminated." Yoshida was so annoyed by these labels, which the foreign press, joined sometimes by the Japanese press and persons in the occupation, often attached to him and the Democratic Liberal Party, that he made a speech defending himself at the foreign correspondents dub on May 11, 1949.[28]

American observers noted a sense of protest in the Japanese election. A leading State Department expert, Max W. Bishop, reported in February after a trip to Japan that the election was a protest vote against the occupation and that "Yoshida has become a symbol of Japan's ability to stand up to the occupation." Edwin O. Reischauer of Harvard University, who became ambassador to Japan in 1961, observed at the same time that "whereas several years ago the Japanese looked upon the occupation as a unified, all-powerful force, centering around an infallible leader, they have come to see it today as a conglomeration of

persons having conflicting views and widely varying abilities.... Even General MacArthur has lost his aura of sanctity.... This irritation with the occupation was significantly demonstrated by the returns of the recent election, which resulted in a resounding defeat of those parties which were tainted with `collaboration' with general headquarters." Both Bishop and Reischauer thought that the communists were expanding their influence in this disturbed situation.[29]

Another sign of the changing times was the departure in December 1948 of Charles L. Kades, the powerful driving force in SCAP for political reform. He had remained in Japan much longer than he had originally expected because he was fascinated by the challenge and importance of his job. In 1947, in a rare meeting with lesser staff officers, MacArthur had asked Kades to stay on until the reform job was done. By the end of 1948 Kades was out of sympathy with some of the ideas coming out of Washington, and he was discouraged by the return of the conservatives to power in Japan. The general asked Kades to explain the situation in Japan to the top officials in Washington and persuade them not to change direction. Kades conducted a one-man campaign and made several important speeches, with the approval of the supreme commander.[30] But the pressures for change in both Washington and Tokyo were too strong to resist.

The signal conservative victory may have caused Yoshida and MacArthur to feel optimistic about the direction of events in Japan. Yet it was evident by 1949 that occupation policies and leadership roles were evolving. Washington was taking a much more active role than before, especially in pressing for economic recovery. MacArthur was still supreme, but no longer unchallengeable. And Yoshida was prepared to play the part designed by U.S. policymakers for a more active Japan and a less interventionist SCAP. MacArthur correctly believed that Yoshida had developed remarkably as a politician and leader. His views on national issues and occupation policies had not changed, but fed no doubt by his election victory, his self-assurance in handling people and problems had grown. The Japanese press thought he was so strong-willed it began to call him "one man," by which the press meant one-man rule.

One of the first fruits of the Draper-Kennan approach to Japan was a directive sent to MacArthur in December 1948 "to achieve fiscal, monetary and price and wage stability in Japan as rapidly as possible, as well as to maximize production for export." The general relayed the directive to Yoshida by letter on December 19, making the rare ac-

knowledgment that he had received it as an "interim directive."[31] This important instruction had been prepared by the National Advisory Council (NAC), a top-level economic advisory body, and approved by the president. Its impact was somewhat blunted a few days later by the no-confidence vote against the second Yoshida cabinet and the hanging of five major war criminals.

The directive set out nine goals, including a balanced budget, increased production, better tax collection, stronger price controls, improved foreign trade procedures, and more efficient food collection. A target date of three months was set for instituting a single exchange rate in place of the existing maze of multiple prices. Most of the points in the directive, other than the exchange rate, had been incorporated in instructions to the Japanese during the previous several years. General Marquat had given the Ashida cabinet a ten-point program very similar to the NAC directive on July 15, 1948. But this time Washington, not merely the economic specialists of SCAP or even MacArthur, was speaking.

Yoshida immediately replied to MacArthur's letter, thanking the general for his "earnest advice and detailed analysis" and noting, somewhat undiplomatically, that the U.S. objectives were ones "which you have repeatedly indicated to my government and I am happy to say that their importance is fully appreciated."[32] The NAC directive had aroused a heated debate in Washington. The Department of the Army and MacArthur opposed stringent stabilization measures and a single exchange rate. Against them were State and Treasury. They compromised by sending the stabilization directive and a special mission to look over the situation.[33]

Yoshida knew little of the battling within the U.S. government over economic policy and probably did not fully appreciate the significance of the new directive. During his subsequent election campaign he said nothing to indicate that a new and tough U.S. program was about to be applied to Japan. He even talked about eliminating the sales tax and providing more government support for struggling industries, almost in contradiction to the new policies. Nor did Yoshida know that MacArthur was worried about the impact the new program would have.

MacArthur had wired Washington on December 12, 1948, expressing strong reservations about the new directive:

[It] calls for the imposition of economic controls probably without historical. precedent. Its implementation will require the reversal of existing trends toward free enterprise ... and negation of many of the fundamental rights and

liberties heretofore extended to ... Japanese society.... Imposed at this time when the Japanese are registering such marked and decisive strides toward their own economic rehabilitation and when the austerity of Japanese life is already reflected in an average monthly wage equivalent to less than twenty dollars United States currency and for whom a 1,500 daily calorie basic ration is still an objective rather than a realization, its effect on the local situation is impossible accurately to gauge.... If the Japanese people follow us ... if capital and management move with vigor and determination ... and if Japanese politicians and political parties faithfully subordinate themselves and their policies and political efforts to the stated objective ... we will succeed. If any of these human forces fail ... explosive consequences well may result, but I shall do my best.

A few months later MacArthur took a less anguished attitude. In a talk with the Australian representative on March 15, 1949, the general said that Draper had insisted on the directive "in order to have something to show to Congress." MacArthur went on to say that "the nine-point ESP [economic stabilization program] was designed to hustle the Japanese." The general was not sure of the wisdom of hustling.[34]

On February 1, 1949, the American whose impact on the Japanese during the occupation was second only to that of MacArthur arrived in Tokyo. Joseph M. Dodge came as financial adviser to the supreme commander to begin what the Japanese called the "Dodge whirlwind." A self-made man who had risen to be president of the Detroit Bank and served as adviser to General Clay in Germany in the early years of the occupation there, Dodge was a determined and tough-minded banker who was nevertheless unassuming in his personal relations, although he was not very popular with some of the SCAP staff, who made him out to be a kind of penny-pinching accountant. He had been recruited for the Japan job by Draper, with MacArthur's consent. President Truman personally asked Dodge to take the job and assured him of full support.[35] Dodge won the confidence of MacArthur, with whom he worked closely, and he gained the respect and friendship of the Japanese leaders, who came to value his judgment and willingness to talk fairly and candidly with them about the issues they faced together.

The goal of both the SCAP and the Japanese economic experts was to reduce the costs of the occupation and prepare Japan for a competitive role in the world economy. Dodge felt the necessary preconditions were price stability and a balanced budget. By the time Dodge arrived, conditions were slowly improving, but indicators were still well below prewar levels. Industrial production had reached about 70 percent of the benchmark 1934-1936 period. The Tokyo price level at the start of

1949 was more than twice that of the year before. Industry and banks were desperately short of capital, so the government facilitated capital accumulation by providing generous loans and subsidies to producers. Foreign trade was entirely controlled by SCAP, although foreign traders had been allowed to do business in Japan since 1947. The trade deficit went up from $352 million in 1947 to $426 million in 1948.[36]

Yoshida told his new cabinet at its first meeting on February 18 that he wanted the nine goals of the stabilization program fully realized. This meant reversing some of the easy-money policies he had advocated during the election campaign. After consulting business leaders, he chose as his new finance minister Ikeda Hayato, a veteran Finance Ministry official and tax expert. Yoshida had come to think that in dealing with Americans new faces and younger men were often preferable to the politicians and businessmen of the old school. This appointment launched Ikeda on one of the most brilliant postwar political careers in Japan, which culminated in his becoming prime minister eleven years later.[37]

Dodge first met with senior Japanese officials on February 9, even before the new cabinet was formed. In a crisp and direct manner, he told them, "The budget will have to be balanced. Unpopular steps will have to be taken. Austerity will have to be the basis for a series of economic measures." One Finance Ministry expert, Miyazawa Kiichi, who later entered the Diet and became a senior political leader, said of Dodge, "We thought he was a terrible old man, but in several years things turned out the way he said." Miyazawa related how the Japanese often found it a useful tactic to play off one group in SCAP against another; this time they decided they would side with Dodge against the "New Dealers."[38]

Dodge and Ikeda met on March 1 for their first serious discussion of the budget, which the government was preparing for the fiscal year beginning April 1. In vivid language, Dodge stressed three points. First, Japan's economy was walking on stilts made of price subsidies and U.S. commodity assistance. These would have to be cut, or "Japan would fall on its face." The budget should show clearly how large these items were. Second, spending by the Reconstruction Finance Bank, then at the ¥40 billion ($111 million) level, was undesirable. It would be a crime for Japan's inflation-bloated economy to spend money labeled for "investment." It was high time to turn off this spigot. Third, excess liquidity in the system had to be sopped up.[39]

Dodge felt Yoshida's political promises to cut the income tax and

eliminate the sales tax were wrong. The sales tax was said to be a bad tax, but no tax was a "good tax." At a press conference on March 1, Dodge restated these thoughts in his pungent way. His stilts metaphor became famous in Japan.[40]

Dodge and the Japanese, led by Ikeda, spent more than one month in almost constant negotiation over the fiscal year (FY) 1949 budget. Both kept in close touch with their principals, General MacArthur and Prime Minister Yoshida, neither of whom knew much about budget complexities but both of whom carefully followed and approved all significant actions. The most contentious items were the income tax and the sales tax, which the Democratic Liberal Party had promised during the election campaign to reduce. Dodge would not permit this. His insistence on an increase of 50 to 60 percent in railway fares and postal fees also gave the Japanese serious problems.

Ikeda became so discouraged early in the negotiations that he wanted to resign, but Yoshida bucked him up and persuaded him to stay. The political pressure on both men from their conservative colleagues was intense, but Yoshida, buttressed by his overwhelming majority, refused to yield an inch. Ikeda said later in his career that he owed all his success to Yoshida sensei , meaning "my mentor Yoshida." Without Yoshida's backing at that point, Ikeda might not have had a later career. The success he and Dodge ultimately achieved in turning around the economy proved to be a tremendous asset for him.[41]