Revelations of Rank

Scholars are unanimous in their agreement that one figure depicted on the now-famous silk banner from tomb no. 1 at Mawangdui represents the deceased, although her precise identity remains to be established (fig. 7).[6] For present purposes, the abundance and quality of objects found in the coffin and the elaborate form of interment provide

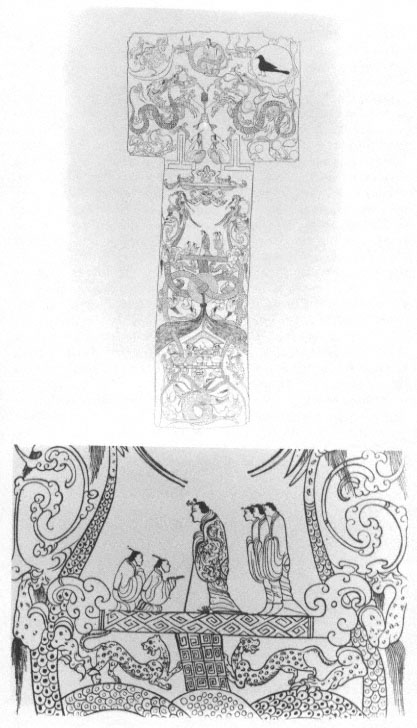

7.

Line drawing of the painted silk banner from tomb no. 1 at Mawangdui,

Changsha, Hunan province, and detail from the vertical section. Length,

205 cm; width of horizontal section, 92 cm; width of vertical section,

47.7 cm. Ca. 168 B.C. (From Hunansheng bowuguan, Changsha

Mawangdui yihao Han mu. )

more than sufficient evidence that the Lady Dai (as many presume the corpse to be) was a member of the nobility. The superb quality of the painting on the silk banner, as well as on the nested coffins, gives ample testimony to the occupant's wealth.

Although the precise functions of the banner and the iconography of many of its specific images continue to be debated, scholars generally agree that the painting in toto represents the journey of the soul (hun ) from its earthly residence to its permanent abode in Paradise.[7] One image, among many, is recognized as the countess.

Standing slightly to the right of center in the composition and noticeably larger than the five figures accompanying her, the figure in question appears in the topmost composition of the vertical strip of the T-shaped banner. From the arrangement of the hair and from the jewels adorning it, we infer that the figure is a woman; Michael Loewe notes that the use of such jewels was limited to the nobility.[8] The elaborate patterning of her robe, in contrast to the plain garments of the accompanying figures, suggests wealth (and is comparable to the fine textiles buried in the coffin). The woman leans on a staff, an attribute that permits us to infer that she is aged. The Bohutong notes that "the stool and the stick serve to support the weak. Therefore the Wang chih [Wang zhi] says: 'At fifty one may carry a staff in one's home, at sixty one may do it in his village, at seventy in the capital, at eighty at (the Lord's) court."[9]

We have readily learned a good deal about the subject of the portrait. From the clothing and hairdress, from the posture and attribute, we observe that the image is a woman, elderly and wealthy. From her size, compared with the size of the other figures in the same scene, we know that she must be the most important person in the scene. These observations are confirmed by the tomb and its contents and by the female corpse, judged from medical examination to have been about fifty years of age.

From her relationship to other figures in the painting, we may infer more about the lady. Behind her and to her right, for example, stand three figures, echoing her profile.[10] Scholars interpret them as females and characterize as male the two kneeling attendants who face the countess and offer food. The gender differentiation is made, presumably, on the basis of hairdo (female) and caps (male). The slight inclinations of the attendants, their hands brought together and muffled in their sleeves, may be taken as the sign of submission.[11] It is reasonable to assume that this gesture of submission indicates that the Lady Dai

occupies a social position higher than those who attend her, whether they are servants or members of a younger generation of her family.

But the gesture of submission does not necessarily mean a lower social status on the part of the one who submits. The same inclination of the upper torso and the same ceremonial gesture of the hands are found in the two figures seated between the pillars (que ) in the horizontal section of the painting. Whatever their specific identities, they occupy supernal positions.[12] As celestials, their status is higher than that of the countess as she is depicted, for, on her journey upward, although she has risen far, she has not yet entered the celestial gates to effectuate her final transformation. We see her en route at the top level of the vertical strip, separated from the gates only by the canopy, and perhaps bidding farewell to earthly familiars. Still in transit, her status is lower than that of the figures who guard the gate. Yet the same gesture of "submission" is made by figures of both higher and lower status. I shall return to the significance of this gesture.

We may assume that the painting was commissioned by the deceased or by her family on her behalf, and that it would be seen by many during the funeral procession preceding interment or other rituals.[13] That it was made especially for the deceased (although it incorporates conventional pictorial symbols of contemporary beliefs about life after death) is clear from the specific representation, as affirmed by her corpse. It is corroborated by the discovery, in tomb no. 3 at Mawangclui, of another painted silk banner with similar iconography. Although damage to the counterpart scene in this latter painting does not allow for close analysis, the corresponding image appears to be that of a male, as befits the tomb of a male.[14]

The painting would also be seen by many invisible, nonterrestrial beings. It is perhaps a statement of fact that at the time of interment the deceased was ready and about to enter Paradise—or perhaps only a pious hope. In either case, the Lady Dai would be recognized from her portrait, which conveys some of her physical characteristics, her wealth, and her status. Had she been depicted in isolation, we might know her gender, age, and wealth. By showing her in context—the entire painting and her location within it, her relationship to other figures—the artist enables us to know her status, social and spiritual. The painting, I suggest, is a report to celestial authorities on the status of the lady's hun, as the wood documents found in tomb no. 3 are a report to underworld authorities on the state of the interred's other spiritual component, his po.[15]

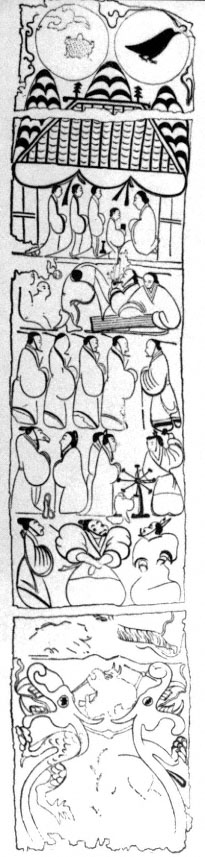

8.

Line drawing of the painted silk banner from

tomb no. 9 at Jinqueshan, Linyi county,

Shandong province. 200 × 42 cm.

Western Han (202 B.C. –A.D. 24).

(From Wenwu 1977.11.)

Similar pictorial techniques can be found on another silk painting of early Western Han from Jinqueshan, in Shandong province (fig. 8).[16] One figure on the second register, larger than those opposed to it, is very likely the deceased. From the relationships of size, posture, and position in the painting, we are able to single out the most important figure, while the color of her robe and her hairdress notify us that the personage is a woman.[17] On the basis of the portrait of the Lady Dai at Mawangdui, we may assume that the seated figure is intended to be a representation of the deceased. It is, in short, a portrait.[18]

Aside from one basic characteristic, that the subject is female, any other information we might glean from this painting about the woman in question must come from examining the relationships just noted. Virtually all pictorial elements found in Han portraits can be interpreted only in terms of their relationships, to each other and within the general context, if we are to understand the "meaning" of the portrait. Even an attribute, such as the staff of the Lady Dai, may have more than one interpretation, depending on its context.

On the fourth register of the Linyi painting, for example, a profiled male figure to the right leans on a staff and faces a row of four erect figures. Although all are garbed almost identically, the seemingly minor differences in the robe of the right figure suggest that they are significant of rank.[19] Thus, the right figure's position vis-à-vis the others, and the small differences in clothing details, mark him as more important than them. His staff can hardly be a sign of age, since he is clean-shaven, whereas two of the males opposing him have moustaches. I interpret his staff, therefore, to be the symbol of mourning—and of his relationship to the deceased as well.

The Bohutong asks, "Why must (the chief mourner) carry a staff? The filial son, having lost his parent, was so afflicted with grief . . . that his body . . . became emaciated and ill. Therefore he carries a staff to support himself."[20]

Perhaps this small figure is a portrait, intended to be like the son of the deceased. Isolated, he could not be identified as such. Depicted in relationship to others, he can be tentatively identified.