The Afro-American Symphony and Its Scherzo

He who develops his God-given gifts with [a] view to aiding humanity, manifests truth.

Afro-American Symphony (1930)

Most of this volume deals with the cultural, biographical, and aesthetic issues that surrounded Still's career. I have chosen to discuss only one work in any detail, the Afro-American Symphony, emphasizing specifically its third movement, the Scherzo, whose score is now included in the latest edition of a widely used anthology.[1] The completion of the Afro-American Symphony in 1930 marks the crowning achievement of Still's self-consciously "racial" period. As Still's best-known work, it is the one most readily available on records, the one most likely to be heard on classical music stations, and the one that has drawn critical examination in any detail from more than one writer.[2] Thus it is and has been the single most influential expression of his aesthetic of racial fusion. In it, he brought one genre, the symphony, to another, the blues, and transformed both in the process.[3] The extreme polarization of these two genres in 1930—by musical language, medium of performance, presence or absence of text, social class, race, audience, implicit moral value, even, arguably, gender—reflects the societal polarizations that Still challenged in this symphony. Newly available sketch materials and notes on the symphony, along with Still's long-available diaries and other published writings, make it possible to reconsider the whole symphony and the Scherzo's pivotal role in it. The quotation of George Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm" and speculation on Still's reasons for citing it make the Scherzo all the more attractive as the locus for a discussion that moves in a concrete way toward an increased understanding of the cultural

interactions that pervade Still's boundary-blurring enterprise. As one follows the composer in his choice of materials and his handling of them, one may detect the voice of the satirist in the Gershwin quotation, or perhaps the fabled West African trickster figure who practiced irony or misdirection to make his point. One may also perceive the cold and merciless logic on which Still, along with other modernists of his time, depended.[4] All three are arguably present in the Scherzo, although only the third of these attitudes is suggested in his several written descriptions of the work, three of them included in the Sources section of this book.

One analytical study, written four decades after the symphony, provides musical detail but no overview.[5] Four more recent discussions deal significantly with the symphony's cultural and historical context. In "'New Music' and the 'New Negro,'" Carol J. Oja insists on the work's double life: "Alongside its preeminent position among black concert works of the early twentieth century, the Afro-American Symphony belongs with a group of pivotal pieces by white composers written in 1930 and 1931, especially Aaron Copland's Piano Variations, Ruth Crawford's String Quartet, and Edgard Varèse's Ionisation . . . . Still led a dual existence, part of which involved treading the same path as young white concert composers of his day and part of which kept him in step with his own people." She points out that his "ideological link" with the white modernists was "fraught with powerful tensions" and that it became "increasingly more tenuous" as he pursued his career as a concert composer. She discusses two concert works (Levee Land and Darker America ) that preceded the Afro-American Symphony as formal experiments leading to various "imaginative" solutions to "the conflict between a more dissonant—or 'ultramodern'—musical style and an identifiably black one." She shows that Levee Land is composed on two planes; one with "conventional blues-derived melodies and harmonies" and another with "chromatic-third relationships that play off a basic trait of the blues." Darker America, however, is sectional, moving between blues-derived harmonies and moments of "intense chromaticism." The contrasting affects are combined in the symphony's finale. Oja concludes that "in the Afro-American Symphony, conventional, blues-derived harmonic practices prevail" and that, overall, "no other composer, either black or white, claimed quite the same turf [as Still]."[6]

Rae Linda Brown takes up the Afro-American as one of three symphonies dating from the early 1930s by three different African American composers. She says, "Although Still was not a conscious participant in the Negro renaissance, his music speaks of the essence of the New

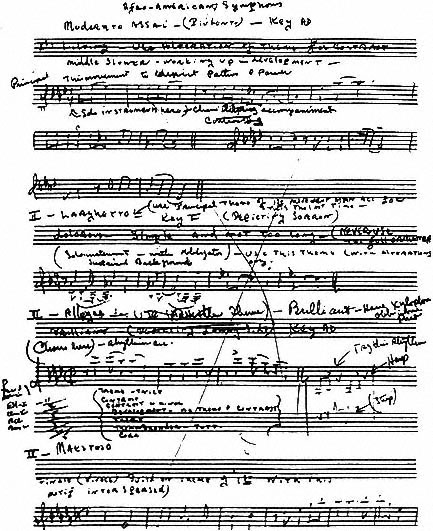

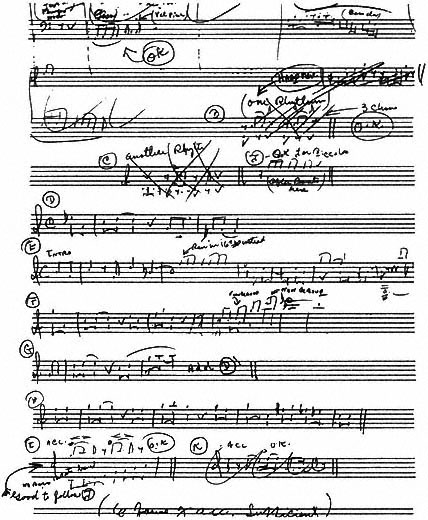

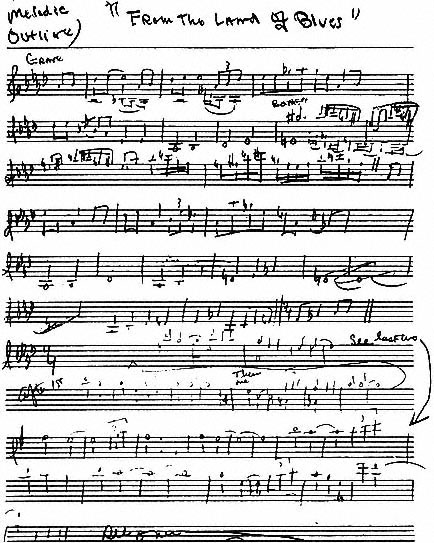

Figure 4.

One-page outline of the Afro-American Symphony , "Rashana" sketchbook.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

Negro." She points out that the primary theme of the first movement of the Afro-American Symphony is accompanied by a "typical blues progression" in a standard twelve-bar blues pattern and that the second movement is built on a related theme in a spiritual style. The third movement's "syncopated cross rhythms [are] clearly rooted in Afro-American dance."[7] Orin Moe's contribution is to begin exploring the nature of the "tension" in the symphony between its "black musical characteristics and those from the Euro-American tradition." His discussion of the symphony amplifies those of Brown and Oja because of his observation that "the black materials fundamentally alter the inherited shape of the symphony" and that "Still juggles . . . with considerable success" the confrontation he has created between the historical symphonic structure and "the stanzaic variation structure of the blues." Oja speaks of the Afro-American Symphony 's aesthetic conservatism from the perspective of contemporary white modernism. Moe remarks further that its "surface conservatism" has prevented it from being seriously considered by critics and prompted its exclusion from surveys of twentieth-century music.[8] Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., develops Moe's ideas and explores the symphony in terms of recent black cultural criticism. He points out that Still's thematic treatment may be heard as employing the practices of African-derived call-and-response and "signifying" as well as European compositional techniques. He argues that Still participated in three contemporary movements, adding nationalism to the avant-garde and the Harlem Renaissance in which the others place him. Floyd correctly identifies Still's avant-garde style as neoclassical. "After rejecting the avant-garde, Still eventually triumphed in the nationalist and Harlem Renaissance realism with the Afro-American Symphony, a work that blended African-American and European elements more successfully, in my opinion, than those of any other composer of the period."[9]

In hindsight, late 1930 was the right moment for Still to attempt his first symphony.[10] He had learned something new, it seems, with each of the new works of the previous fifteen years. Still's earliest-known multi-movement work for orchestra is an early American Suite recently located in the archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It was composed no later than early 1916. Not until that summer, when he first worked for W. C. Handy, was Still immersed in African American popular music and converted to its advocacy; at that point he apparently also achieved basic technical competence as an arranger.[11] Given Still's later interests, this suite is remarkable for its lack of reference to African

American popular music making. Its Native American reference ("Indian Love Song") hints of the turn-of-the-century Indianist movement, widespread among American composers; this may be suggestive of MacDowell or even of Dvorak[*] , whose sojourn in the United States in the 1890s acted as a catalyst for the nationalist movement in American music. These are the other known multimovement instrumental works that preceded the Afro-American Symphony, with their dates of composition:

American Suite (1916 or earlier)

Three Negro Songs (1921) (orchestral despite its title)

From the Land of Dreams (1924) (includes three voices used "instrumentally")[12]

From the Journal of a Wanderer (1925)

From the Black Belt (1925)

Log Cabin Ballads (1926)

Africa (1928–1930)

Like the single-movement Darker America (1924; discussed at length by Harold Bruce Forsythe elsewhere in this volume), all of these works after the American Suite used African American musical materials, and all received performances, with generally increasing success. (Three Negro Songs was probably performed for an African American audience in Brooklyn; the others were heard by generally white audiences in New York or elsewhere. From the Land of Dreams, believed lost for decades, is discussed briefly in the introduction.)

On the basis of this achievement and of a generally supportive critical response, couched in stereotyped language though it was, Still's confidence in his skill as a composer was at a high point. His diary gives not only a time frame for the composition of the Afro-America Symphony but also a sense of Still's state of mind, his manner of working, and his other activities. When he began it, he had just returned from Rochester, New York, where he heard the first stunning performance of Africa with full orchestra on October 24, 1930. His diary entry reports the performance: "God sent me success today. Africa was a sensation."[13] On the same trip, Still conferred with Harry Barnhart, a well-known choral conductor then at Rochester, about his ballet Sahdji, completed three months earlier and scheduled for its premiere in Rochester the following spring.[14] His yearlong contract with Paul Whiteman had expired four months earlier, and Whiteman was not in a financial position to re-

hire him. Although he had no steady job, a well-received new orchestration for the "Deep River Hour" radio show a few weeks earlier (October 9) may have encouraged him in his search for regular work and suggested that the window of opportunity to work on another large-scale composition might not last too long.[15] As we shall see, the opening of Gershwin's show Girl Crazy on October 14 may also have triggered a sense of urgency about this long-contemplated project.

In spite of all this, the diary shows that Still started work on his new symphony in a mood of discouragement. Both the difficulty of finding regular work as an arranger and domestic problems outweighed the satisfactions of his compositional achievements, even the recent triumph of Africa . These are the entries that record his work on the symphony, complete for the days in which he reports such work:

Oct. 30. Start working on Afro-American Symphony. Things look dark. I pray for strength that I may do just as God would have me. Would that I never did anything to displease him. I believe that he will straighten out conditions. I must not lose faith. I must not complain.

Nov. 5. Raining. Gloomy. Thanks to God I received some splendid ideas for the Afro-American Symphony last night.

Nov. 20. Rehearsal. My arrangement did not sound well. But who knows how it will sound on the air [;] tonight tells the tale. God's will be done.

Completed sketch of Afro-American Symphony's first movement. May God grant it succeeds.

Nov. 28. Praise God. Well along in 3rd movement of Symphony. Call from Willard Robison.[16]

Dance of Wilberforce Univ. Club.[17]

Dec. 2. Cold today. Worked on Symphony. Thank God for the inspiration He gives me. I am so unworthy. To think that God in His majesty would take thought of such as me! Let me seek to draw closer to Him. Let my greatest desire be that of doing His will in all things.

Dec. 5. Was able to accomplish much today in scoring of "Afro-American Symphony."

Dec. 6. Completed scoring 3rd Movement of Afro-American Symphony today.

Dec. 26. Nothing of unusual interest. Symphony progressing rapidly.[18]

As several of these and other entries suggest, Still was heavily involved in seeking paying work as the symphony progressed. Given that distrac-

tion, the speed with which he worked on the new symphony is even more impressive. In a letter to Irving Schwerké dated January 9, 1931, Still remarked the completion of the entire project shortly after New Year's, about ten weeks after he had begun.[19] (Other remarks in that letter—his most forthright discussion of the racial obstacles he faced, and his only known mention of leaving the United States as a serious possibility—reinforce the notion that this was a period of great personal stress.)

Two early notebooks in Still's hand at William Grant Still Music give a great deal more information concerning the creation of the symphony than has previously been available. I will describe them here and return to them as needed later in this chapter. The first, its front cover decorated with cigar bands, is actually a theme book. It is labeled on the cover "Still 1924," one of the years when Still was studying with Varèse. Its thirty-eight unpaged leaves contain 444 numbered themes, many of them labeled with one-word "affect" suggestions (e.g., "voodoo," "lament," "spiritual"). The first forty-three appear in a consistent fair hand, in ink, seemingly copied all at once from an earlier source. Thereafter the themes are written in a less consistent script and sometimes in pencil; these are most often in the hand that Still used for the fragmentary sketches that fill blank pages and margins in many drafts and fair copies of his own scores. Some earlier themes (as late as #178) are marked "good" or "better" in Still's hand. Sketches having to do with the uncompleted opera from the late 1920s, "Rasbana," fill much blank space to the right of the shorter themes. That Still returned to this theme book for some time after it was begun in 1924 is evident, for the composer took themes from it for many works of the late 1920s and early 1930s (such as Africa and Blue Steel ); one was used as late as 1938 or 1939, when he was working on the opera Troubled Island . Several themes used in the Afro-American Symphony (only one of them so labeled) are among them. Several that suggest Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm" raise the old question about the ultimate source of Gershwin's melody, to be discussed below. In the last few pages are sketches of other works either destroyed or not completed. There are unlabeled, partially harmonized sketches on three staves, a numbered group of "chords," a verbal outline of "Ode to the American Negro: For the Oppressed" (very likely a program sketch for Darker America, composed in 1924), a

pasted-in, typed sketch for the ballet La Guiablesse (dated 1927 in the thematic catalog), and a page too damaged to read labeled "Material for From the Black Belt " (dated 1926 in the composer's thematic catalog). "From the Land of Blues," labeled a "melodic outline" and filling about a half-page, is one item to which I will return. While it is likely that Still began to use the theme book during his study with Varèse, it is not at all clear when he stopped using it as a place to notate his melodic ideas. Nineteen twenty-seven, the last year for a work known and completed that is referred to by name, may be a reasonable cutoff date.

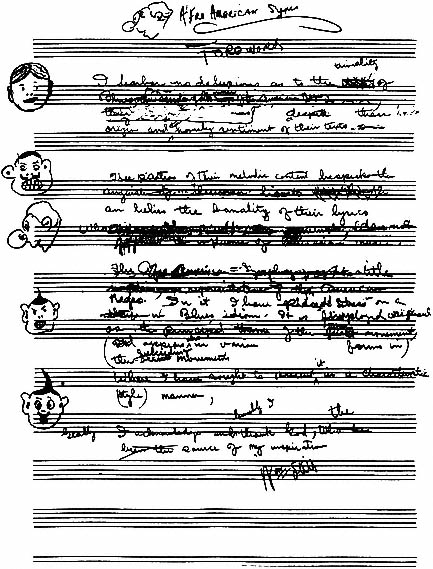

The other notebook bears the label "Material for Rashana" on the cover and is stamped "DEC 1926" on the inside.[20] It is somewhat shorter than the 1924 theme book. After a sketch of Africa, it is paginated in Roman numerals by the composer. A series of numbered themes, now classified by affect (e.g., "Passionate Themes"), some with references to numbered themes in the 1924 theme book, follow. These seem to have been organized with a view toward the aborted opera. Some notes on orchestration suggest that this book, too, was started during Still's study with Varèse. Most of this book was left blank at that time. Still returned to it to sketch out the Afro-American Symphony in late October or early November 1930, as noted in the diary. Starting approximately in the middle of the book, he began with a one-page outline of the symphony (see fig. 4), then an outline of the first movement, from which he methodically began to compose, writing out a series of "treatments" of his thematic material for each movement. The first two movements occupy the last part of the book; then Still returned to his starting point and worked steadily forward as he composed the last two movements. From the diary entries cited above, these sketches can be dated quite accurately as between October 30 and early December, when the diary shows him occupied with scoring the work. The "Rashana" sketchbook includes Still's draft foreword to the symphony (see fig. 5):

I harbor no delusions as to the triviality of Blues, the secular folk music of the American Negro, despite their lowly origin and the homely sentiment of their texts. The pathos of their melodic content bespeaks the anguish of human hearts and belies the banality of their lyrics. What is more, they, unlike many Spirituals, do not exhibit the influence of Caucasian music. The Afro-American Symphony, as its title implies, is representative of the American Negro. In it I have placed stress on a motif in Blues idiom. It is employed originally as the principal theme of the first movement. It appears also in various forms in the succeeding movements, where I have sought to present it in a characteristic (style) manner.

Greatly I acknowledge and humbly I thank God, the source of my inspiration.

Wm. Still[21]

Both Still and (later) Arvey provided a series of typed, undated descriptions and program notes for the work, one of them in the Arvey monograph later in this volume, that address his intentions in composing the symphony.[22] One of these begins, "The 'Afro-American Symphony' is based on an original theme in the 'Blues' idiom, employed as the principal theme of the first movement, and reappearing in different forms in the course of the composition." After a sizable quotation from the draft foreword (see above), these continue:

I seek in the 'Afro-American Symphony' to portray not the higher type of colored American, but the sons of the soil, who still retain so many of the traits peculiar to their African forebears; who have not responded completely to the transforming effect of progress. Therefore, the employment of a decidedly characteristic idiom is not only logical but also necessary. . . . In a general sense, one may apply to the movements the following titles:

1. Longing

2. Sorrow

3. Humor (expressed through religious fervor)

4. Aspiration.

When judged by the laws of musical form the A.A.S. is somewhat irregular in its form.[23]

Example 2 shows Still's blues theme as it appears in the "Rashana" sketchbook and as it is used at the opening of the first movement in the finished score, both as the introductory figure and as the principal theme. The introductory figure, played by the English horn without accompaniment and in an improvisatory style, suggests the early folk blues that became the basis for the twelve-bar "classic" blues of the 1920s. Still's main theme, as many commentators have noted, is a "classic" blues, and is harmonized as such. Frequently varied in the first two movements, it is radically transformed in the third, as I will show.

At the end of the sketches in the "Rashana" notebook is the poetry Still copied out from the work of the turn-of-the-century dialect poet Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906), one excerpt for each of the four movements. Still did not identify the excerpts by title in the sketchbook or in either edition of the published score. Like many a nineteenth-century tone poet and even some of his modernist contemporaries who wanted

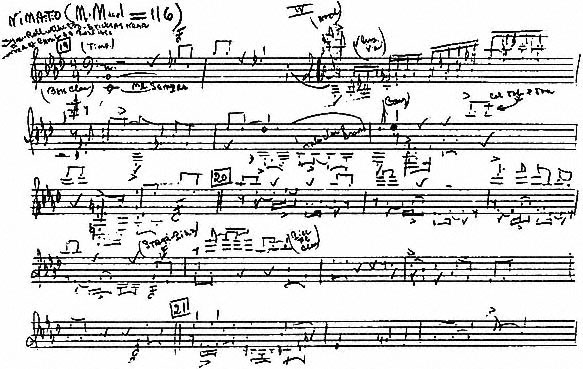

Figure 5.

Still's draft foreword for the Afro-American Symphony, "Rashana" sketchbook.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

From top to bottom the sketches are Still, Donald Vorhees, Paul Whiteman, Still,

and the Li'l Scamps (popular cartoon characters of the day).

Example 2.

Still's blues theme as it appears (a) in the initial outline of the

symphony ("Rashana" sketchbook) "depicting pathos and power"; (b) in the

sketchbook under "Form of 1st Movement," assigned to the oboe; (c) in the

completed score as a free, unaccompanied English horn solo at the opening of

the first movement; and (d) in the completed score as the primary theme in

the first movement, a twelve-bar "classic" blues played by the solo trumpet.

(Compare with the themes in "William Grant Still and Irving Schwerké.")

Courtesy William Grant Still Music. Used by permission.

their music to stand on its own, he later downplayed the significance of these quotations. Nevertheless, the excerpts were carefully selected from four different poems, and they appear in both published versions of the score. In fact, they serve as a guide to Still's intentions in this symphony. Although the single words he chose to characterize the affects of three of the four movements seem to reflect the meaning of the poetry directly, the couplet and the affect word he chose ("Humor") for the Scherzo movement have a far richer meaning than an audience unfamiliar with Dunbar's poetry (as white concert audiences would generally have been) might have supposed.

Consider, then, all four of the excerpts Still selected for epigraphs in

the context of longer quotations from Dunbar's poems. The poems used as epigraphs for the first two movements refer to the dreams and sorrows of the former slaves. The opening stanza of "Twell de Night Is Pas'," prefacing the opening movement with its blues theme, reads:

All de night long twell de moon goes down,

Lovin' I set at huh feet,

Den fu' de long jou'ney back f'om de town,

Ha'd, but de dreams mek it sweet.

Still quotes the close:

"All my life long twell de night has pas'

Let de wo'k come ez it will,

So dat I fin' you, my honey, at last,

Somewhaih des ovah de hill."

The first stanza of "W'en I Gits Home" is attached to the slow movement, with its spiritual-like melody:

It's moughty tiahsome layin' 'roun'

Dis sorrer-laden erfly groun',

An' oftentimes I thinks, thinks I,

'T would be a sweet t'ing des to die,

An go 'long home.

The final movement, with its hymnlike, modal opening hardly changed from the initial one-page outline in figure 5 and its lively finale, was first assigned the final stanza from Dunbar's "Ode to Ethiopia":

Go on and up! Our souls and eyes

Shall follow thy continuous rise;

Our ears shall list thy story

From bards who from thy root shall spring,

And proudly tune their lyres to sing

Of Ethiopia's Glory.

Both printed editions of the score bear this rather better known stanza from the same poem:

Be proud, my Race, in mind and soul,

Thy name is writ on Glory's scroll

In characters of fire.

High 'mid the clouds of Fame's bright sky,

Thy banner's blazoned folds now fly,

And truth shall lift them higher.

The only quotation not in dialect, either stanza is appropriate to the apotheosis of the finale that follows the final transformation of the blues theme in the Scherzo.

For the Scherzo movement, the situation is more complicated. The poem, "An Ante-Bellum Sermon," from which the quoted couplet is drawn, signals that the movement is about much more than "humor (expressed through religious fervor)." It plays on the meaning of the word "scherzo" as a joke, revealing Still in the role of Trickster. The whole of Dunbar's poem shows how effectively Still used the "minstrel mask" to reflect his sense of racial doubleness. However trivial the lines quoted, the poem is in fact about Emancipation and citizenship, matters not at all trivial, thus pointing to the Scherzo as the crux of the symphony. Here are some longer excerpts from the poem; the quotation used by Still appears in italics.

We is gathahed hyeah, my brothahs,

In dis howlin' wildaness,

Fu' to speak some words of comfo't

To each othah in distress.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

So you see de Lawd's intention,

Evah sence de worl' began,

Was dat His almighty freedom

Should belong to evah man,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

But when Moses wif his powah

Comes an' sets us chillun free,

We will praise de gracious Mastah

Dat has gin us liberty;

An' we'll shout ouah halleluyahs,

On dat mighty reck'nin' day,

When we'se reco'nised ez citiz'—

Hun un! Chillun, let us pray![24]

This "Ante-Bellum Sermon" is delivered in the voice of a black preacher, himself a slave. As the sermon proceeds, the biblical references allude more and more pointedly to his and his listeners' intolerable situation. Asserting that "de Lawd will sen' some Moses / Fu' to set his chillun free," he cautions "I'm still a-preachin' ancient, I ain't talkin' 'bout today," and admonishes his listeners "Now don't run an' tell yo' mastahs / Dat I's preachin' discontent." He further reminds them "Dat I'm talkin'

'bout ouah freedom / In a Bibleistic way." At the climax of the poem, which includes the couplet Still uses as his epigraph, the full contemporary application of the sermon comes out, only to be stopped in mid-word—"citizens"—one imagines by fear of being overheard.

The "Rashana" sketchbook contains Still's working plan for the entire symphony (see fig. 5). His original plan calls for a key scheme from movement to movement of A-flat to F to A-flat and to G-flat for the fourth movement, which would presumably have finished either in A-flat or in F minor. In fact he followed this plan until the final movement:

Movement 1 ("Longing"): A-flat major tonal center. The blues theme introduces modal chromatic alterations. An excursion to G major in a slower section provides a contrast in tempo that elaborates on the blues theme but is not confrontational, as formulaic nineteenth-century prescriptions for first movements of symphonies often require.

Movement 2 ("Sorrow"): F major tonal center, with many chromatic alterations in keeping with the blues theme.

Movement 3 ("Humor"): A-flat major tonal center, moving toward and mixing with A-flat Dorian.

Movement 4 ("Aspiration"): F minor tonal center. The movement begins with a lengthy slow section that establishes E major from an unlikely modal beginning on C-sharp minor before moving triumphantly to its jubilant ending in F minor.

In the Afro-American Symphony, Still uses simultaneous contrasting stylistic levels as well as alternation and blending of contrasting European- and African-derived styles, refined from his earlier experiments (described above by Oja) in Levee Land and Darker America . The "double consciousness" of W. E. B. Du Bois permeates the work.[25]

To represent the European-derived style, Still chooses not the chromatic harmony of the modernists but a system of very clear if somewhat irregularly used key relationships. This choice is a technical reflection of his often-mentioned departure from the ultramodernist aesthetic of his teacher Varèse and others, made partly in reaction to his discovery (starting with From the Land of Dreams ) that audiences could not recognize his fusion practice if they were occupied with puzzling over ele-

ments: of European-derived modernist expressiveness. It also provides a framework in which Still can portray both his nominal subject—the "old" post-Civil War Negro (rather than the "New" one of the Harlem Renaissance)—and his underlying aesthetic purpose—to demonstrate through his music a "great truth," the profound and continuing influences and borrowings between two parallel but racially divided cultures.

Still uses the major-minor system to supply a modal framework rather than a rigidly functional harmonic one. He uses the major scale to represent the Euro-American culture, while the Dorian minor, built on the same tonic but using the minor third and the lowered seventh degree, serves for the African-derived blues scale. Such chromaticism and harmonic tension as arises comes most commonly from the interaction between the major and minor thirds (and less often the sevenths) that result from the simultaneous use of these scales. This interaction is clearest in the Scherzo, where A-flat major and its parallel Dorian are superimposed on each other; I will discuss it further below. This is of more than technical interest because it reverses the standard European symphonic practice, involving the progression from minor to major.[26] In the course of all four movements, Still's symphony moves from A-flat major to its relative minor on F, something of a musical pun on the major-minor relationship of his third movement. The modal usages and the play on motion from major to minor are technical realizations of Still's purpose as he stated it in his draft foreword—to use the idiom of the blues specifically because "it does not exhibit the influence of Caucasian music."

The dominant-to-tonic (V-I) relationship, which permeates the European tradition as a way to define sections and set up rhetorical confrontations, is downplayed in Still's scheme, though it is not entirely absent. (For example, a dominant pedalpoint introduces both movements 1 and 3, and there is a contrasting section on the dominant key in the final F minor section of the last movement.) Leading tones and perfect authentic progressions (i.e., affirmations of dominant-to-tonic harmony) are relatively rare as elements of the work's macro-structure. They are abundant, however, within small melodic units, especially in the Scherzo. In the more "African" second movement with its strong blues coloring, the melodic and harmonic materials are both more chromatic and less functional, evading a commitment to a Western drive-to-cadence. The absence of formal authentic cadences and the avoidance of even a suggestion of modulation in the slow, spacious opening of the final movement create a strongly modal sense, leaving the listener with a certain

ambiguity about the tonic. (See fig. 4, the theme associated with movement 4.) In this movement, the slow section appears three times, each time followed by a contrasting section on F minor, the movement's destination and the overall tonal center of the symphony. The climactic final Allegro is remarkable not only for the absence of any dominant-to-tonic progression but also for the virtually complete absence of the leading tone, in this case, E natural. The earlier slow, modal sections centering on E (as a tonic) literally preempt that note from its leading-tone function, so essential for the traditional nineteenth-century Western sense of closure. In the coda, the bass line moves from F up a minor sixth to D-flat, avoiding the customary European move from V to I to the very end while at the same time providing (along with the English horn solo in the first movement) a subtle homage to the Dvorak[*] of the New World Symphony .[27]

Table 1 is a diagram of the Scherzo; example 3 shows its themes. As we saw from the poetry that Still chose as an epigraph for this movement, the Scherzo's "humor" is weighted with meaning; it supports the high seriousness of Still's privately stated comment to Forsythe about "presenting a great truth" through this symphony.[28] This "Hallelujah" is no mere celebration of innocents mimicking their own "primitive" religion, as Still had initially intended and white audiences might have been led to assume. It wears the minstrel mask and bears the weight of the human comedy as fully as any other moment in the symphony, and perhaps in Still's entire output. No one can doubt that the poem's narrator intends the biblical assurances of freedom for Moses' people to apply to his own people as well. The meaning of the scherzo/joke is thus doubly played. The "clever fox trot" (as one hapless critic described the Scherzo)[29] that began with a lighthearted minstrel tune (theme 1A) not only gains depth from its exposure to a more authentic African American influence, it is transformed by the declaration in theme 2A to imply a progression from superficial white minstrel representation to a statement of aesthetic and political emancipation.

Changes of tonal center are entirely missing from the Scherzo in Still's realization, a highly unusual procedure for any movement that pretends to be the product of the European tradition, and the only movement in this symphony for which this is true. This absence heightens the importance of the motion from major to Dorian minor that takes place

Table 1.

Afro-American Symphony

Form of the Scherzo

Example 3.

Themes from the Scherzo. Theme 1A, "Hallelujah!" is given as it appears the first and

last times. Three forms of theme 2A and two forms of theme 2B are given.

Used by permission.

without any change of tonal center. (A brief barbershop passage in measures 51–53 is the one moment when there is any doubt at all about the key center.) Still outlined the Scherzo in multiple sections identified by their themes. The principal theme, labeled 1A, is transformed in the course of the movement from a straightforward, lively statement in the

major mode to a richer and more exuberant mix of major and minor. Theme 1B, which usually follows 1A, mixes the two modes from the start.

These two themes (especially 1A, with its tenor banjo afterbeats) carry the "minstrel show" affect. Theme 2A, orchestrated for trombones and other low-pitched instruments, contrasts sharply with themes 1A and 1B in its driving, fanfarelike affect, its off-beat accents, and its irregular length, different in each of its three statements. So different is the affect of 2A that it seems to appear on an expressive plane separate from the other themes in the movement. Appearing shortly before the midpoint of the movement, it provides a strong contrast to 1A, the "Hallelujah!" that Still intended in his initial description of this movement as portraying a "janny sect," the "old-time" African American religion in which motion is an essential part of worship.[30] This theme, unequivocally in the Dorian (minor) mode, depends entirely on melodic action for its cadences. This interrupting, "Emancipation" theme (my characterization) is derived from the most clearly African-derived idea in the symphony, the haunting English horn solo that opens the first movement. (See examples 2c and 3 above.) Theme 2B, "Emancipation," is the one theme that is stated first on the tonic, then a fifth higher, on the dominant, and finally on the tonic, but its appearance on the dominant does not change the tonal center of the movement even temporarily. With its repeated high notes and emphasis on the descending fifth, theme 2A presents a radical transformation of the "classic" blues statement of the first two movements, a transformation that logically must accompany the disappearance of the minstrel mask.

The stanzalike "treatments" of themes that lead to the sectional contrasts-with-continuity characteristic of the work's individual movements are particularly clear in the third movement. The constantly changing statements, especially of themes 1A and 2A (see ex. 3 above) are reminiscent of both older New Orleans improvisatory practice associated with the beginnings of jazz and very long-standing European-derived variation practice.[31] Figure 6 shows a series of such treatments in the sketchbook, and figure 7 is the beginning of Still's melodic outline for the movement, showing varied treatments of theme 1A. In his scheme, the "treatments" involve variations in instrumentation and accompaniment figures as well as small melodic decorations and changes.

The sectionality of this movement is strongly rooted in African-derived practice as well as in the theatricality of the minstrel show; its key structure is likewise, as Still said of the entire symphony, "somewhat irregular in form." Thus it is awkward to describe the Scherzo in Euro-

Figure 6.

Melodic "treatments" of theme 1A, Scherzo, "Rashana" sketchbook.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

pean-derived terms. Even though Still attached the term "development" to some of his "treatments," suggesting a sonata form of sorts, the Scherzo could just as well be characterized in several other ways. Although the detailed outline shows it as a ternary form, the movement could also be thought of as a large-scale barform suggestive of the aa1 b form of the classic twelve-bar blues, as a rounded binary form, or

Figure 7

First page of Still's sketch for the Scherzo, "Rashana" sketchbook.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

maybe even two rather simple ABA forms that happen in sequence. More simply, it might also be seen as revealing some formal, trickster-like sleight of hand.

The initial presentation of the minstrel tune (theme 1A) in the Scherzo is accompanied by a countermelody identical to the opening of the chorus of a hit pop tune of the day. Gershwin's show Girl Crazy, featuring the infectious "I Got Rhythm," opened October 14, 1930, as Still was preparing to travel to Rochester for the performance of Africa and just two weeks before he began to compose the Afro-American Symphony . The quotation appears once, immediately after the introduction, in the horns, in a spot where it is intended to be heard, meant to be a reference listeners would clearly understand. A second, following statement is broken up by octave displacements and changes in instrumentation; then the fragment of this catchy tune is heard no more. It seems entirely possible that Still changed his initial conception of this movement (as shown in fig. 4) specifically to accommodate this quotation. Indeed, he made more revisions from his original outline of the symphony in this movement than he did for any of the others, scrapping both the original main theme and his initial outline for the movement. He went back to his 1924 theme book to borrow an early tune he had labeled "Hallelujah!" years earlier.

Why does this current pop tune appear in the Scherzo of this symphony? The question puzzles modern performers, even seems to embarrass them; in one recent recording, the quotation is all but inaudible, seemingly deliberately made so.[32] I believe that Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm" reinforces the meaning of that first statement of theme 1A, in its major/minstrel form in which the African American presence is perceived solely through the eyes of white interpreters, thereby speaking to the meaning Still intended for the movement and for the symphony as a whole. We hear the start of "I Got Rhythm" intact only once; then the movement goes on to its real business, the transforming shift toward a black-influenced, modally inflected minstrel tune with the very political "Hallelujah" and "Emancipation" themes folded through it.

Why did Still choose this particular tune to make his point? Where did the "I Got Rhythm" melody come from in the first place? Here the answer grows more speculative. Modern listeners more familiar with Gershwin's song than Still's work assume that Still borrowed Gershwin's melody, but some older African American musicians believe it was Still's

Example 4

Scherzo, first statement of theme 1A, with countermelody in the

horns and afterbeats in the tenor banjo.

Used by permission.

Figure 8

Theme 48, "Hallelujah," used as theme 1A of the Scherzo, "Rashana" sketchbook.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

to begin with. Evidence from the theme book supports them—partly. The story about Still, Gershwin, and "I Got Rhythm" also draws on anecdotal evidence, all collected well after the fact. There are several versions. Judith Anne Still tells of her father walking down a New York City street with Eubie Blake and hearing the tune as they walked past an open door. Blake asked wasn't that Still's tune from Shuffle Along days, and Still acknowledged that indeed it was. Blake expressed anger at the theft; Still's response was more sanguine. In a published interview from 1973, Blake went into much greater detail:

Do you know William Grant Still? . . . He's a personal friend of mine. [Eubie darts to the piano.] Do you know this tune? [He plays Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm."] . . . All of the fellows in my orchestra would be playing around, having a good time, but Still would be playing this little tune over and over. [Eubie hums the melody.] So I heard the darn thing so much that one day I said to him (not while we were playing in New York, but later when we were in Boston), "What's the tune you're playing?" Still answered me, "One day you'll hear it in a symphony, an American symphony!" . . .

Now, one day Dooley Wilson . . . comes up to me and says, "Boy, have I got some music; this is swell music!" I played the music for him—it was all Gershwin music—and when I got to the piece "I Got Rhythm," I didn't have to look at the music. I knew it! You know, once I hear a tune—if it's a good tune—I don't forget it. . . . Now, one day I was walking down 56th Street, and I saw Still standing in front of the Carnegie Hall entrance. . . . I said, "You know that tune you used to play?" I hummed it for him. "Is that your tune?" He looked at me but didn't answer. So I said, "I saw the music to 'I Got Rhythm' and it's the same as your tune." Still said, "Yeah? Well, I'll see you later." He would not say that Gershwin stole the tune; he is just that kind of man.

[Interviewer] How do you explain it?

Oh, that's easy. Still used to teach Gershwin orchestration. He had to go to Gershwin's place on Park Avenue to give the lessons, and while he was waiting for Gershwin to come down—Gershwin was always late—he would play this darn tune on his oboe. Gershwin heard the tune and took it. Now Gershwin probably didn't mean to take it or steal it because he didn't have to. The man was a genius! But that tune was Still's tune. It could happen to anyone.[33]

Blake's version is demonstrably inaccurate on at least one point. In a section of the interview not cited here, he has Still conducting his own symphony at Carnegie Hall. Actually, the New York premiere of Still's symphony (which must have been the Afro-American ) took place in late 1935, long after Girl Crazy had closed. Still did not conduct, nor did he conduct any of his concert works in New York City. (He was living in Los Angeles by then and probably did not attend the perfor-

mance.) In fact, Blake's association of the theme with the Boston run of Shuffle Along argues against Gershwin having heard it in the theater, for Gershwin is much less likely to have attended performances outside of New York.[34]

In October 1996, Dominique-René De Lerma wrote of interviewing Still about this when the two met in 1969:

Still told me (I was also an oboist) that he doodled from the pit before Shuffle Along performances [i.e., in 1921 or 1922] with this little figure—. . . and knew that Gershwin was in the audience. The figure, of course, generates the Gershwin tune. . . . The same figure with the same rhythm appears in the third movement of the Afro-American Symphony in the horns, with the statement of the theme. Still had an expression on his face when we talked about this which clearly suggested he felt Gershwin had appropriated his doodle. I don't think it is extended enough to justify a copyright violation, but it is a strange coincidence and Still's reaction might be symptomatic of his vigilance.[35]

Gershwin was well known to seek out performances by black musicians, and Shuffle Along would have been an obvious show for him to have attended, maybe more than the one time Still mentioned to De Lerma.[36] Affirming once more that Gershwin was interested in Still's work, Verna Arvey notes that Gershwin attended the performance of Still's Levee Land at a concert presented by the International Composers' Guild at Aeolian Hall, January 24, 1926. In the same essay, probably from the late 1960s, she wrote of Gershwin's attendance at a performance of Shuffle Along .

One Negro musical show which took New York by storm in the early Twenties was Shuffle Along. George and Ira Gershwin and most of the other Broadway celebrities attended it, some more than once. . . . As the show went on and on, the players in the orchestra began to get tired of playing the same thing over and over again, so very often they would improvise. Most of them had a special little figure that they added, as they felt so inclined. Still's figure was melodic. Later, when he was composing the Afro-American Symphony, he used the small little figure, wedded to a distinctive rhythm which he had originated in the orchestration for a soft-shoe dance in the show, Rain or shine.[37]

Arvey was reporting what Still had told her. The awkwardness of her telling betrays her unfamiliarity with a milieu outside her own experience, but it also reflects a struggle to get the story as Still remembered it. Her words seem to amplify De Lerma's report about what happened. Later, Still wrote generally about musical borrowings in American music, though not in detail about his own experiences. In "The Men Behind

Example 5

Numbered themes from the 1924 theme book suggestive of the

"I Got Rhythm" motif. All are lightly crossed out, meaning that Still had used

them. Themes 249 and 251 are marked "Good—Negroid"; 260 is marked

"Good for Land of Blues."

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

American Music" (1944), Still writes with a certain ambivalence, mainly about plagiarism in commercial music:

As for George Gershwin, who wrote so much in the Negroid idiom, there are many Negro musicians who now claim to have done work for him, arranging or composing. I have no way of knowing whether any of these claims are justified. I do know that Gershwin did a great deal of unconscious borrowing from several sources (not always the Negro) and that he did some conscious borrowing which he apparently was generous enough to acknowledge, for he gave W. C. Handy a copy of the "Rhapsody in Blue," autographed to the effect that he recognized Handy's work as the forerunner of his own. . . .

Quite often colored musicians claim to have had their creations or their styles stolen from them by white artists. In many cases these tales may be dismissed as baseless rantings. But there have been so many instances in which they are justified that one cannot ignore all of them. I have learned this from my own experience and from the experiences of my friends in the world of music.[38]

In support of his statement, he describes hearing an arrangement of his own over the radio that was ascribed to another arranger.[39]

Still never claimed "I Got Rhythm" for himself, at least in writing. Yet the 1924 theme book and the 1926 "Rashana" sketchbook offer evidence that partly supports the claims to precedence made in his behalf. The theme book shows several themes that begin with the tune's opening four pitches, sol, la, do, re (see ex. 5). In every case, the opening melodic contour is similar, but the tempos are slower, syncopation is not notated, and the melodies go off in other directions rather than (or before) turning back on themselves. Most memorable is its use as shown in figure 9, "From the Land of Blues," the "melodic sketch" in the "Rashana" sketchbook not otherwise identifiable.

Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm" depends for its impact on three musical elements in addition to its text: a four-note gap-scale figure that turns back on itself, a syncopated rhythmic pattern, and a drive to a cadence that rounds it off. Still's themes, as they are notated in the examples we have, all lack the syncopation that is associated with Gershwin's tune. A handwritten notation on a draft of the Arvey essay quoted above, very likely made at Still's behest, reinforces Arvey's reference to the 1928 musical Rain or Shine as the place where Still, in one of his orchestrations, used both the melodic pattern and the syncopated rhythmic figure.[40] At least for now, this clue leads to a dead end. Only two songs from Rain or Shine are deposited in the Library of Congress; six more were returned to the claimant several years after they were deposited for copy-right, and another six were never deposited.[41] One cannot know which (if any) of the fourteen might have quoted the "soft-shoe dance" to which Arvey refers, or whether the pattern occurred only in a section that never reached print or copyright. We are left with what appears to be Still's word—which is reliable in other cases but which cannot be verified in this one. Blake, who seems to have embroidered his story in order to make his broad point about unacknowledged borrowing, went out of his way to acknowledge that Gershwin's use of Still's idea was inadvertent: "it could happen to anybody."

It is obvious that the ascending gap-scale figure (sol, la, do, re, or do, re, fa, sol ) fascinated Still. How Still improvised on it from the orchestra pit during the run of Shuffle Along (or in Gershwin's living room), we cannot know. Comparison of Still's and Gershwin's treatments of it shows both their similarity and where they parted company. Still's failure to claim the song as his own may simply represent his acknowledgment

Figure 9

Melodic sketch, From the Land of Blues, 1924 theme book.

Courtesy of William Grant Still Music.

Example 6

Still's and Gershwin's themes compared. Used by permission.

that he used it differently from the way Gershwin did, and/or that the distinction between something improvised and something written down was very important to him. Perhaps he feared that any serious claim on his part would be dismissed as "baseless ranting." Since the melodic motive we know about is not used in the same way by both composers, at least in the surviving written versions, the question of primacy becomes less relevant. The difference in their use of the same basic melodic material seems far more interesting than the similarity. For Still, it was a brief blues gesture to be extended at will; for Gershwin, a snappy, open-and-closed eight-bar song-and-dance phrase. The contrast points to the operation of different sensibilities powerfully influenced by the cultural position of each composer, the specific tasks in which each was involved, and the unpredictable vagaries of individual talents and predilections.

Despite his lack of action, Still must have known that, one way or another, he had helped Gershwin reach that melody. Perhaps Still could see

the interaction on a broader scale. For him the melodic figure belonged to the blues, and to the African American past. By quoting Gershwin's version where he did, as part of the whites-in-blackface minstrel representation with which the Scherzo begins, he suggested where Gershwin's tune fitted into his fusion aesthetic with a subtlety appropriate to the mythical Trickster. Moreover, the appearance of "I Got Rhythm" along with Girl Crazy in mid-October 1930—assuming that dates when Still first heard it—must have pushed Still to begin writing the symphony he had contemplated for so long.[42] It might even have provoked him to rethink the Scherzo, to abandon for something far richer his initial idea of portraying the "janny sect" that he had laughed at when his mother had taken him along during the summers she taught rural African Americans without access to regular schools. One imagines his thought that Gershwin's use of that material aptly demonstrates the "minstrel mask" of the past, the one imposed from "outside." His own treatment pointedly addresses the "real" past: slavery, Emancipation, the blues. He felt secure, perhaps, in his own sense of the "authenticity" of his own application, with the scale, with his constantly changing thematic "treatments" that modern commentators may think of as "signifying." If Still stimulated Gershwin from the pit in the Shuffle Along production or as the orchestrator of Rain or Shine, Gershwin's commercial adaptation in turn provoked Still to sit down and compose the symphony he had contemplated for so long, and even to add this tricksterish layer of meaning.

In one of her "Scribblings," Verna Arvey records an anecdote about Still's friend Harold Bruce Forsythe and the Afro-American Symphony . She writes that when Forsythe heard about Stokowski's telegram announcing that the fourth movement would be performed on a lengthy 1936 Philadelphia Orchestra tour, he visited Still's home and asked to see the score of the symphony, which was unfamiliar to him. He looked at it for a while and announced that he would write to Stokowski supporting the performance, remarking that he was the only one who knew what the symphony was about. Arvey took this as another symptom of Forsythe's insufferable arrogance; yet Forsythe may have been right in his judgment that most audiences would have listened to the symphony without seeing the complexity of the cultural message Still had inscribed in it, much less the topicality of the Gershwin reference, a seemingly minor point in the overall work.

It is clear enough that given the abyss that separated whites and blacks

in Still's America, no composer who identified as European-American or "white" would or could have composed with the sensibility revealed in this or others among Still's self-consciously racial works. Still's symphonically treated blues decentered the expected neat enclosure of the African by the European for white concert audiences.[43] Whether his actual audiences were prepared to receive his work as he intended it to be interpreted is another question entirely, and may explain his own comment, "This symphony approaches but does not attain to the profound symphonic work I hope to write; a work presenting a great truth that will be of value to mankind in general."[44]

While the symphony itself is successful as a work of art that continues to be performed regularly, neither it nor later works by Still had (or could have had, given the relatively small general audience for concert music in the United States) an impact comparable to that of the blues' entry into popular music with its mass audience. Moreover, the racial barrier in concert music remained higher than for popular music. Two decades after he composed the Afro-American Symphony, Still himself acknowledged that there was not yet parallel recognition for African Americans in concert music and opera, that "the serious Negro musician who is said to have 'arrived' today still is confronted with all sorts of preconceived notions."[45] Certainly no single work could revitalize or restore in 1930 the black concert audiences that had existed in the early 1920s, nor could it create the genuinely integrated audience to which his fusion aesthetic ultimately looked forward.

Still conducted his quest to find a speaking subject position in concert music and opera with unique persistence and skill over his long creative career. Though his first concert works came almost sixty years after Abolition, the need to establish and redefine the status of African American musicians by composing in the elite genres of symphony and opera remained critical in a society where blacks were overwhelmingly confined to "popular," that is, "lower-class," music making. He went to great lengths to fight his way into the world of high musical literacy, to find a place as a speaking subject in the world of concert music. The Afro-American Symphony stands as a landmark in this project.