PART 4

THE BATTLE FOR ASIA TO THE BATTLE FOR THE WORLD

Chapter 11

Gung Ho for a Wartime China

On a bleak January day in 1938 Snow walked with Rewi Alley beyond the perimeter of the International Settlement into war-ravaged Japanese-occupied Chinese Shanghai. He felt both depressed and angry as the two surveyed the human and material wreckage left by the protracted battle for the city. (Chiang had committed his crack divisions to the hard-fought battle for the city, which had lasted from August to November 1937, with a loss of two hundred fifty thousand Chinese troops.) "Miles of debris: bricks, stones and broken timbers. Hardly a house standing intact," a diary entry noted. Unburied and decomposing bodies of Chinese soldiers and of civilians caught in the intensive Japanese bombing and shelling lay everywhere. "Walking along one saw here and there a clenched fist sticking up from the soil or an arm or a leg." Half-starved people scrounged among the corpses for any money or valuables to buy food. In sharp contrast, at the Metropole Hotel in the settlement "silk-gowned, pomaded Chinese blades" were absorbed with the dancing girls in shimmering white silk that dung to them "like gauze." How "degenerate" the bourgeois Chinese residents of Shanghai, and how fine and courageous the peasant soldiers of China! China's hope, Snow wrote, lay not in corrupt, gangster-ridden Shanghai, but in the vastness of the land and people beyond it.[1]

Snow was equally outraged that no provisions had been made to evacuate any of China's small modern industrial plants, mostly concentrated in or near Shanghai. There had been no advance moves to organize and prepare the workers to salvage their machines and move with them to the unindustrialized interior. "But any such advance arrange-

ments," Snow later dourly wrote, "were rendered impossible under a Government which feared Shanghai labor as much as, if not more than, the Japanese." The poignant sense of loss and of lost opportunity was accentuated for Snow by his New Zealander companion on these Shanghai rounds. Alley, then chief factory inspector under the International Settlement's municipal council, could reconstruct for Ed the histories of hundreds of such destroyed workshops and of their harshly exploited workers. Hundreds of thousands of industrial workers had been idled, and the foreign settlements were jammed with some two million refugees, most of them destitute.[2]

This was the context and mind-set in which the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives (CIC) took form in the early months of 1938. In his characteristically understated and self-effacing manner, Alley eloquently summed this up the following year: "We have brought together engineers and cooperators, and have started a chain of small industry throughout the country. We have made a few engines work that would otherwise have rusted. Put a few people to work who would otherwise have sat in refugee camps. Produced some of the necessities that a people must have whether they are at war or not." And as Ed wrote to a colleague of his own deep commitment to the project, "I could not any longer consider myself a bystander; there was too much work to be done; and without waiting for anybody's invitation, I threw myself in (as [the ample] Anna Louise Strong would say) where my weight counted most."[3]

The cooperative movement was primarily the "invention" (Snow wrote in Journey ) of Rewi Alley and the two Snows. The original idea and much initial "energizing" of the other two carne from Peg. As Ed told the story in a graceful preface to Peg's 1941 book on the CIC, industrial cooperatives were "first of all the brain child of Nym Wales." The subject of cooperatives had come up at a Shanghai dinner party attended by the Snows. Their host, John Alexander of the British consular service, had enthusiastically pushed the cooperative cause as the solution to the world's ills. Peg vigorously rejected the idea: "As usual, she overwhelmed her opponent," Ed wrote. Yet within a day or so she came strongly around to the concept, but for producer rather than consumer traits, with particular applicability to China's grim wartime situation. Such industrial cooperatives could give productive work to refugees, mobilize idled. skilled labor, and create a decentralized chain of small workshops utilizing the resources of China's vast interior, away from concentrated urban areas vulnerable to Japanese occupation or bombing.[4]

According to Helen Snow, the very next morning after her encounter with Alexander, "the solution to China's chief problem came to me in a flash. Why not organize the Chinese workers into cooperatives owned and managed by themselves, financed by labor hours instead of cash capital?" Under her "usual intellectual prodding," Snow related in his Battle for Asia , Alley and he soon saw the light on the great potentialities of industrial cooperation. Peg "stood over" him, Alley later recounted, and said, "'Now look here, Rewi, what China wants today is industry everywhere.... I tell you Rewi, you say you like China, you ought to drop this job of making Shanghai a better place for the Japanese to exploit, and do something that will be useful at this time. The Chinese are made for cooperation.' This she said and much more," he dryly added.[5]

Alley, already working on ideas for building up industry in the interior, went home and typed up a plan based on the concept of a chain of small-scale producer cooperatives throughout unoccupied China. Ed then turned this into a finished version, which was printed in pamphlet form by J. B. Powell's Review . Snow came up with the term "industrial cooperatives" (which became known as Indusco abroad from its cable address), and Rewi with the gung ho logo, the Chinese equivalent of Indusco that could be literally rendered in English as "work together."

As I noted, Evans Carlson took on the Gung Ho slogan for his famed wartime Marine raiders. To him it represented the spirit of common resolve and equally shared burdens and rewards he had perceived in both the Communist Eighth-Route Army and the CIC movement. Through this avenue Gung Ho entered the American vocabulary to convey an attitude of rather naive "can do" enthusiasm. Truly, there was much of this latter spirit in the expansive claims and aspirations for CIC made by its founding trio. It was proclaimed to be the economic basis for unifying and strengthening resistance forces (including support for Communist-held guerrilla areas), for advancing political democracy, and promoting social and economic change. It was "a people's movement giving encouragement to progressive tendencies," Helen Snow declared, and a "healthy 'middle way' common economic program to prevent a civil war between the Right and the Left in China." Industrial cooperation, Ed wrote, "offered the possibility of creating a new kind of society in the process of the war."[6]

The Snows and Alley gathered with eight others in a Shanghai restaurant in April 1938 and formally constituted the group as a preparatory committee to promote the cooperative project. A prominent Shanghai banker and patriot, Xu Xinliu (Hsu Sing-loh), chaired the committee.

His financial contacts and enthusiastic support were invaluable in these early months; his death that August when his plane was downed by the Japanese on a flight from Hong Kong into China was a serious blow. Snow had talked with Xu in Hong Kong on CIC business just a few hours before his departure. Xu's death "shocked me beyond expression," Snow wrote J. B. Powell. He was "a rare personality of his class indeed, a generous and sincere and honest man, and one of the few first class financial brains in China."[7]

Just as Xu had been an exception to Snow's image of the "degenerate:" Shanghai bourgeoisie, he soon met a further exception of a different sort in the British ambassador to China, Sir Archibald Clark-Kerr (later Lord Inverchapel), who subsequently served as ambassador in wartime Moscow and then Washington. As another early convert and ally in the cooperative cause, he clearly did not fit Snow's unsympathetic view of such representatives of the British Raj, or for that matter any other stereotype of the stuffy diplomat. "Archie" and Snow would become: trusting and lasting friends. Clark-Kerr had read Red Star before coming to China and looked Snow up on arrival in Shanghai in early 1938. Though then representing the highly conservative Chamberlain government, he was himself vigorously "anti-Axis, anti-Franco and anti-Japanese," in Snow's words. He confided to Ed in Hankou (also called Wuhan, for the tri-city complex of Hankou, Wuchang, and Hanyang) well before that city's fall to the Japanese in December 1938 that its Nationalist defenders needed some of Madrid's no pasarán spirit. (Snow was clearly of like mind.) A craggy featured, ruddy faced Scotsman ("all he needed was a feather in his head to be an Indian chief"), he impressed Snow with his infectious wit, kindliness, initiative, and self-confidence. "He stands for the highest type of British official—a rare diplomat," Snow entered in his diary.[8]

Snow succeeded in convincing the ambassador of the merits and practicality of the Indusco plan, and of Alley as the ideal leader to make it work. Clark-Kerr then "sold" the package to the Nationalist government in Hankou—primarily through Madame Chiang and the Generalissimo's Australian adviser, W. H. Donald. They were probably the two people with the greatest influence over the Generalissimo and represented as well the staunchest anti-Japanese elements in the regime. Madame Chiang pressured her brother-in-law, Finance Minister H. H. Kung, to back the project with money. He in fact became president of the board of directors of the CIC Association under the executive branch of the government, of which he was then also president (pre-

mier). In this capacity, Kung "assumed active direction over all CIC policies, finances, and appointments."[9]

In Hong Kong Snow gained the support of T.V. Soong, who agreed privately to back CIC with a substantial loan. T.V., the "liberal" member of the Soong family and a financial expert and banker, was then outside the government and on less than cordial terms with Kung. With Madame Sun's enthusiastic support also secured, the Snow-Alley trio of cooperators had managed to corral the full spectrum of the Soong clan, from the Chiang-Kung ruling branch on the right, to T.V. in the center, and Soong Qingling on the left.

Already in Shanghai the British ambassador had arranged for Alley's immediate separation from his post under the Shanghai municipal council administration. With his unconditional release and pension monies in hand, Alley gambled all on the CIC project. He was soon in Hankou where, with Madame Chiang's firm support, he was appointed chief technical adviser under Dr. Kung, of the now formally established organization in August 1938. (Alley would also wear a dual hat as field secretary under the CIC's international committee set up in Hong Kong in January 1939.) After many "wearying hours in Hankow talking about our cooperative scheme," Snow wrote Powell from Hong Kong later that month, "(I) had the satisfaction of seeing it launched." The movement was going ahead, he added, "despite all sorts of political intrigue and obstruction centered around it." In describing these developments more confidentially to Bertram (then in England) later that year, Snow wrote that "we had manipulated the fuehrers into compliance with a program which normally they would have regarded with shocked horrification as distinctly rouged."[10]

The fact that the cooperative scheme could get off the ground with the backing of the Nationalist government attested also to the heady atmosphere then prevailing in Hankou. For a moment in time, that temporary capital became a somewhat romantic symbol of a seemingly politically united, all-inclusive, and optimistic spirit of determined resistance to the Japanese enemy. It had taken on (rather unrealistically) a kind of Chinese Madrid symbolism ("a genuine popular front capital," Bertram recollected)—an international focal point, especially for the left, in the worldwide antifascist struggle.[11]

The auto tycoon Henry Ford and the Irish-American Presbyterian missionary Joseph Bailie were unorthodox links in the Indusco chain. The latter had first come to China in 1890 and had early on seen his mission in terms of "helping the poor as opposed to saving souls." In his

view, "hungry Christians cannot be good Christians." He had been a principal founder of and professor at the College of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Nanking and took the lead in promoting rural reconstruction programs. He saw rural educational, medical, and economic development as the foundation for a productively self-supporting, independent Chinese nation and people. He stressed the dignity of labor and deplored those who treated the Chinese worker merely as a coolie. "My theory of life," he declared, in reference to the medical condition of the Chinese countryside, "is that we can never have real culture so long as the so-called cultured can look upon such degradation as we have here without doing all in its power to remove it." In all this Bailie was truly, as Alley said, "the ancestor of Indusco."[12]

This was true in a broader sense as well. Among his many ideas and projects for human betterment in China, Bailie urged Henry Ford in 1920 to consider establishing one or more auto plants and support facilities in China, and in conjunction with this to take in groups of one hundred Chinese students for on-the-job practical engineering experience in a training program at his Detroit works. "I want you to go to China and open up," he told the Ford people, "and it will save you an immense amount of trouble to have a lot of tried men at hand." Ford duly provided such training to youths selected by Bailie, most of them graduates of American engineering colleges. These were to be a new breed of educated Chinese who combined theoretical learning with hands-on work experience at the factory level, not the usual returned student aspiring to and prepared only for a bureaucratic career back home. Bailie thus constantly agitated against what he considered "white-collar engineers." He tended to idealize Ford as a model entrepreneur and benefactor of the American worker, who would come to China to do equally well by the Chinese. "Is there no way," he somewhat naively wrote Ford's secretary in 1921, "whereby when whatever company is organized, the shareholder would receive no more than a definite interest on their money invested, while the balance of the profits after treating the workers as Mr. Ford knows how, would be used for giving elementary education to those villages where very often not a single literate person can be found?"[13]

Though Ford eventually lost interest in a China auto venture, many Ford factory school alumni, most of them Christian and with engineering degrees, would become the core technical-engineering staff of Indusco. With the help of some Ford returnees, Bailie also conducted technical programs for poor factory apprentices and young workers in schools attached to major industrial plants in Shanghai. All these student protégés came to be known as "Bailie Boys."

Alley first met this unusual missionary in 1928. Bailie soon became a mentor and inspiration to the young New Zealander. (It was Bailie who had persuaded Alley to spend his summer vacation in 1929 in the northwestern famine area where he first met Snow.) Bailie "was a great American," Alley wrote in 1940, "standing out as a giant in this twilight where we grope so feebly and do so few of the things we are capable of doing." Discouraged, and ill with cancer, Bailie returned to America in 1935 to be with his family in Berkeley, California. After undergoing surgery, he knew he had at most a few bedridden months to live. "So he faced the issue as he had always faced issues," Alley recounted, "waited till people were away from home and quietly shot himself." The Bailie Boys' role in CIC, and Alley's work in connection with the cooperatives, including establishing a number of Bailie Schools for poor village youths modeled on the missionary's work-study Shanghai project, made a fitting memorial to the old man.[14]

During the 1930s Alley befriended a number of Bailie's engineers in Shanghai, a few of whom worked at high-level jobs for the American-owned Shanghai Power Company. He recruited these skilled and experienced men—still imbued with the Bailie spirit—for CIC, at great personal cost to them of income and security. The secretary-general of CIC and the four administrative heads under Alley were all Bailie Boys, as were others who held key posts in the various regional field headquarters. Their extraordinary importance was underlined by the fact that CIC in those years had a total of only twenty "first-class engineers." The secretary-general, K. P. Liu, had been a model county magistrate in Anhui province where he had organized, as he proudly wrote Bailie shortly before the latter's death, cooperative societies for afforestation, fishing, and credit; built roads and a hospital; and ousted the racketeering local tax collectors.[15]

The CIC planners had set an overly ambitious goal of thirty thousand field units by the end of 1940. (Carrying this further, Helen Snow declared in 1940 that CIC "could probably build 480,000 cooperative factories" for the cost of a one-hundred-million-dollar American battleship.) While such numbers were never even remotely achieved, at its peak in 1940 the movement did have 1,867 functioning societies with just under thirty thousand members, with perhaps a quarter million people in all dependent on Indusco for a livelihood. The "Indusco line," Helen Snow grandly wrote, "stretches in a vast crescent from the deserts of Central Asia to the southern sea." With five main headquarters and depots throughout the country these "vestpocket" industries (Snow's term) operated on three "lines": a first or front line of mobile "guerrilla

industries" in the battle zones and behind Japanese lines; a second or middle line of semi-mobile units in the fluid areas between the war fronts and the rear; and a third or rear line in unoccupied "Free China" of more permanently established basic industrial enterprises and the technical and other support services for all three zones.

CIC ran training and vocational centers, clinics, printing and publishing houses, and literacy classes for cooperative members and their families. It operated small mines, machine shops and refineries, chemical, glass, and electrical works and produced a broad variety of goods for both civilian and military needs. Using the wool-raising resources of northwestern China, Indusco units were able to produce some three million winter blankets for the Chinese army through 1942, though not without stretching the cooperative principle to include large numbers of hired contract workers.[16]

CIC's organizational principles and procedures were incorporated in a model constitution drawn up in Chungking during 1939 by cooperative experts and CIC people. It was a lengthy legalistic document and, in Douglas Reynolds' words, "suffered from bureaucratic and intellectual excess." Essentially, as Snow described it, a cooperative unit was financed through low-interest loans and credits. Each worker became a shareholder entitled to a vote. Through deductions from wage earnings the workers bought over their shares, thus paying off the loans and establishing a genuine cooperative. Profits were to be allocated, in prescribed percentages, to reserve, welfare, and industrial development funds or, as bonuses to staff and workers, paid in shares and cash. Each factory unit: was envisaged, as Alley expressed it to Helen. Snow, "as one link in a coordinated chain of production," organized into local federations under each of the five regional headquarters. In the final analysis, as Reynolds. states, it was not "CIC's fine procedures and regulations" but only' proper leadership in the field that could protect and serve members' interests.[17]

Despite the enormous obstacles it faced, and the inevitable deviations in practice from its ideals and principles, CIC had merits and workability and seemed to many a promising democratic prototype for the future—"tomorrow's hope," Snow called it in his glowingly Red Star-like portrayal of Indusco in Battle for Asia . CIC also attracted the attention of Nehru in India, who closely followed its progress. He avidly read both Ed's Battle for Asia (in its British edition, Scorched Earth ), and Helen's China Builds for Democracy (the latter a gift to him from Madame Sun). On Ed's volume, he wrote that "no part of it held me so much as the

chapters dealing with the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives." Nehru emphasized the applicability of the village industry concept to India as well as China. "Possibly the future will lead us and others to a cooperative commonwealth," he concluded in a foreword to the Indian edition of Helen's book in 1942. "Possibly the whole world, flit is to rise above its present brute level of periodic wars and human slaughter, will have to organize itself in some such way." With such shining vistas, so assiduously fostered by the Snows in their publicity work, CIC also became a banner for rallying foreign support for China's overall war effort. And garnering such support, particularly in the West, may have had a certain effect in bolstering the more steadfastly anti-Japanese and forward-looking elements in the Chinese government.[18]

From the start CIC faced the financial and political problems that stemmed from its governmental connection. Kung released funds earmarked for CIC only in dribs and drabs; there were constant cash flow crises alleviated by bank loans and monies collected through committees organized in Hong Kong and the West, and among overseas Chinese in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Alley and other key staff members lived on a pittance, often dipping into their savings for personal and CIC expenses. As of January 1939, for example, Alley had received only one month's salary since joining CIC the previous July. Snow devoted much of his time and energies to the project during his final three years in Asia, at considerable cost to his own work and to his financial and physical well-being. "End of my second month here, working on Indusco! What an ass!" he dejectedly recorded in Hong Kong in June 1939.[19]

Kung, known irreverently to CIC insiders as "the Sage," for his reputed descent from Confucius (Kong [Kung] Fuzi) was both a plus and (increasingly) a minus for Indusco. On the down side were his penny-pinching, foot-dragging mode of support, his profit-oriented mentality, and his innate suspicion of the "popular front" character of the movement. Additionally, in partnership with his wife, the eldest Soong sister, he engaged in speculative and other nonproductive activities. Snow alleged in a July 1939 diary entry that Madame Kung was "fishing around" to get Indusco to help her establish "model factories," possibly in Shanghai, which would earn a "modest 10%" on her investment. Snow also reported that the Kungs still owned "immense properties" in Shanghai, though he added that most of their money was held abroad. These activities at the top reflected the pattern of self-enrichment prevalent throughout the bureaucracy, and which the cooperatives found it more and more difficult to stave off.[20]

Yet in the early years Kung was also CIC's protector in high places. He was after all considered second only to the Generalissimo in the government hierarchy. "Dr. Kung is certainly to be congratulated," Helen Snow remarked in her book on the cooperatives, "upon the fact that he has not permitted the CIC to fall into the grasping hands of Chungking politicians." The "fulsome praise" accorded Kung and Madame Chiang in CIC publicity material, Snow unenthusiastically noted to Jim Bertram in March 1939, was "the necessary line." Kung, educated in American-sponsored missionary schools, and with degrees from Oberlin College and Yale University, savored such image-making publicity the Indusco promoters gave him in the West. To offset his work to guard the cooperatives from rival factional efforts to absorb or destroy them were Kung's own administrative shortcomings and obstructionism, and the "grasping" qualifies of many in his entourage. As a Christian convert and a former YMCA secretary, "Daddy" Kung had a "soft-hearted" (and Snow would add "soft-headed") side to him, which could also be a bit of a trial. He tended to view CIC in paternalistically philanthropic terms that misinterpreted its mission and trivialized its significance. He approved of such Gandhi-like "spinning societies," he told Snow, for they could keep virtuous village girls working at home, away from the evil influences of big city factory life.[21]

At the same time, Indusco's founders had a left-leaning agenda of their own that was bound to collide with the entrenched political and economic interests and constituencies of the Nationalist regime. ("What is the color of your [CIC] organization?," W. H. Donald queried Ida Pruitt, who became executive secretary of Indusco's international operations.) The Snows and Alley aimed to use the cooperatives to advance the kind of popularly based and politically inclusive war effort they found lacking in Kuomintang policies. Donald had also already reacted negatively and sharply to Alley's suggestion of two Hankou-based Communist leaders (one of them Zhou Enlai) for membership on CIC's board of directors. Alley was merely (if naively) expressing his and the Snows' view of the cooperative movement as a united front operation encompassing and aiding both the Communist and Nationalist resistance effort.[22]

Actually, as Alley much later revealed, he was in touch with Zhou Enlai and other Communist liaison people in Hankou in the organizing stages of Indusco. They advised a more politically circumspect CIC approach. It should seek out prominent anti-Japanese "patriotic democrats" for leading roles in the organization, work with and through the

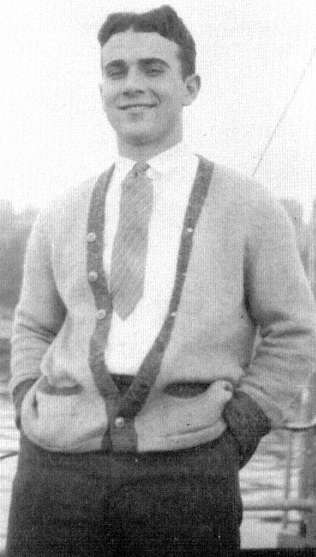

Edgar Snow at age twenty-two, as he embarked from New

York in 1928 for the Orient.

Edgar Snow's mother, Anna Edelmann Snow. Date unknown.

Courtesy Mildred and Claude Mackey Papers, University of

Missouri-Kansas City Archives.

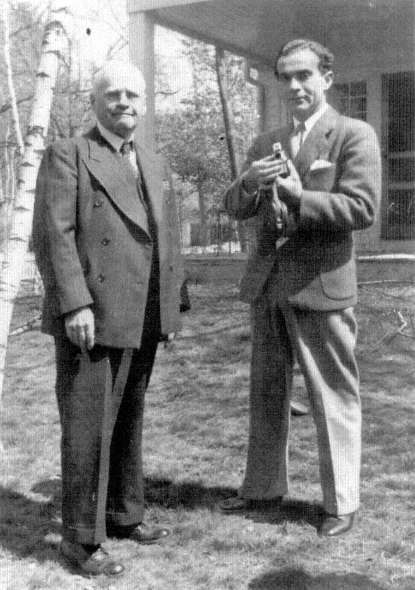

Edgar Snow and father, J. Edgar, in 1941. J. Edgar and Snow's sister, Mildred, and

her husband, Claude Mackey, were then visiting Ed in New York and Howard in

Boston. Ed had not seen his father and sister since leaving Kansas City in 1926.

Courtesy Mildred and Claude Mackey Papers, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Archives.

Edgar Snow and sister, Mildred Mackey, 1941. Courtesy Mildred and

Claude Mackey Papers, University of Missouri-Kansas City Archives.

Mildred Mackey and Howard Snow, 1941. Courtesy Mildred and Claude

Mackey Papers, University of Missouri-Kansas City Archives.

Chiang Kai-shek, J. B. Powell (China Weekly Review editor), and Edgar Snow,

probably 1929 or 1930, in Nanking. Powell, then correspondent for the Chicago

Tribune, had interviewed Chiang. Courtesy of J. B. Powell Papers, Western

Historical Manuscript Collection, University of Missouri.

Peking student marchers, December 9, 1935 (December Ninth Movement). Photo taken

by Snow.

Helen (Peg) Foster Snow, in Peking in the mid-1930s. Showing her with her dog

Gobi, and her riding attire, the photo exemplified one aspect of the life-style of the

Peking "foreign set" in those prewar years.

Helen Snow in the Philippines, 1939, where the Snows resided

from late 1938 through 1940. She was deeply involved in Indusco

promotional work there. Courtesy of the late Polly Babcock Feustel.

Agnes Smedley, 1940s. Courtesy of Mary C. Dimond Papers,

University of Missouri-Kansas City Archives.

Edgar Snow on arrival in the Red district in the northwest, 1936.

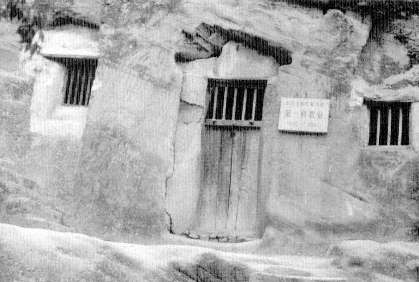

Mao's preserved cave dwelling in Bao'an, where Snow spent long nights

interviewing the Communist leader in 1936. Photo by Evelyn Thomas.

Mao and wife, He Zizhen, Bao'an, 1936. Mao later divorced her to marry the actress

Jiang Qing.

Hillside cave dwellings of Mao and other Red leaders outside Yan'an, where Snow

interviewed the chairman in 1939. Considerably more "upscale" than Bao'an, it

remained Mao's headquarters until 1947. Photo by Evelyn Thomas.

George Harem (Dr. Ma Haide) and wife, Sufei. Inscribed on back,

"To dearest Rewi from George and Sufei in Yenan [Yan'an], 1945."

Courtesy of Mary C. Dimond Papers, University of Missouri-Kansas

City Archives.

Edgar Snow and Evans Carlson, in the Philippines, 1940.

James Bertram during visit with the

Snows in the Philippines, 1940.

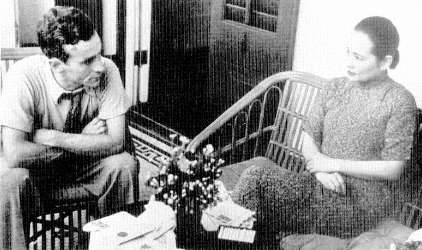

Edgar Snow and Soong Qingling (Madame Sun Yat-sen), in later 1930s. Courtesy of University

of Missouri-Kansas City Archives; gift of Soong Qingling

Foundation, China.

Edgar Snow as a war correspondent at Stalingrad, February 1943, after the Russian

victory there. Courtesy of Smedley-Strong-Snow Society, China.

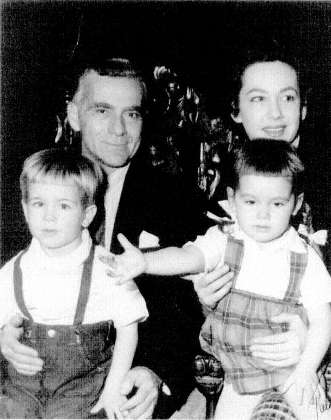

Edgar and Lois Snow with children, Christopher and Sian, 1954.

Courtesy of Lois Wheeler Snow.

Edgar and Lois Snow with China group in Geneva, 1961. From left to right, Chinese

consul general Wu, Lois Snow, Madame Wu, Chen Xiuxia, Gong Peng, Edgar

Snow, Qiao Guanhua (Ch'iao Kuan-hua), and Israel Epstein. Aside from the consul

general and his wife and the Snows, the others were in Geneva for the 1961-1962

international conference on Laos. Foreign ministry officials Qiao and his wife, Gong

Peng, were old China friends of Snow's. Courtesy of Lois Wheeler Snow.

Rewi Alley outside his Peking home, 1960s. In much the same garb he trekked

through China's hinterland in his wartime Indusco work. Courtesy of Mary C.

Dimond Papers, University of Missouri-Kansas City Archives.

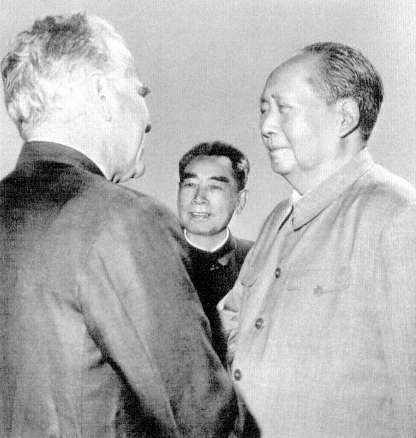

Edgar Snow, Zhou Enlai, and Mao in Peking during Snow's 1964—1965 China trip.

Edgar Snow and Puyi, the last Qing emperor, in Peking during Snow's 1964-1965

visit.

Edgar Snow with friend and literary agent Yoko Matsuoka in Japan, at

a journalists' seminar she arranged for him in Tokyo, 1968. Courtesy of

Seiko Matsuoka.

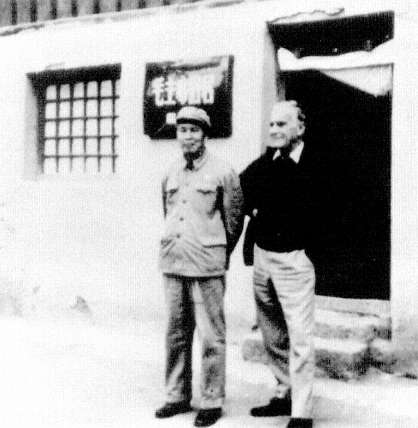

Edgar Snow and Huang Hua, in front of Mao's Bao'an cave, during Snow's final

1970-1971 China visit. Note the diplomat Huang's "politically correct" cultural

revolutionary attire.

Lois and Edgar Snow at a Peking dinner party, 1970.

Edgar Snow at home in Eysins, Switzerland, September 1971, just months before

his death.

The Snows' home in Eysins. Courtesy of Lois Wheeler Snow.

Kuomintang, and develop as much international support as possible. CIC should not go into Red-controlled areas "except in the course of popular front work that covered all unoccupied regions," Alley related. This counsel seemed in keeping with the orthodox Communist interpretation of the united front line at the time—to avoid any moves that might undermine the joint Kuomintang-led struggle. It was a line with which Snow would have his differences.[23]

In any case, the dynamics of the war, with its great expansion of Communist power vis-à-vis the increasingly conservative and debilitated Nationalists, could only heighten the inherent tensions between the two camps. The tiny CIC united front forces, relying heavily on foreign support and funding, could in no way set the course in China's increasingly polarized wartime politics. The reverse, as Douglas Reynolds's study of the CIC has demonstrated, was the case. CIC thus faced such formidable obstacles as continuous financial cutbacks and crises, anti-Communist vendettas against many of its staff, and persistent efforts at takeover ("reorganization") by rightist elements and time-serving and often corrupt bureaucratic hangers-on. As a crowning irony, what remained of the original CIC would find short shrift and internment under the Communists after 1949.[24]

But in the relatively unified political climate of the early war years, and with an eye on CIC's interests, Snow conspicuously tried to emphasize the positive when writing on the Chiang-Kung patrons of Indusco. A 1940 item he did on the three Soong sisters, who were displaying their joint backing of CIC, was a case in point. In their support of the cooperatives, Snow rather transparently concluded, "One perhaps sees in best focus the generous instincts which all three sisters possess." Ed could hardly have put his heart into even so mildly likening his idol, Madame Sun, to Madame Kung. (Madame Sun, in passing on scandalous tidbits to Snow on the profiteering activities of H. H. and Madame Kung, herself cautioned Ed, for Indusco's sake, not to put any of it in print.)[25]

In a Foreign Affairs article on the Generalissimo published in the summer of 1938, just as CIC was moving into place under Nationalist auspices, Snow showed a willingness, despite the past, to give the Chinese leader the benefit of his (Snow's) doubts, and to accord Chiang high marks for his stubbornly courageous, if autocratic, war leadership. "His outstanding virtues," Snow wrote, "are courage, decision, determination, ambition and sense of responsibility." (Snow had a personal interview with Chiang in Hankou that July, a meeting that could take place, he surmised, because the Generalissimo "did not know who I was.")

Snow took even what he considered Chiang's most pernicious past policies (appeasing Japan while waging ruthless war against the Reds) and managed to give them a considerably more affirmative twist. He thus declared, "we may be absolutely certain that Chiang exhausted every practical possibility of reconciliation with Japan before the current bloodbath began." And as for the Generalissimo's "implacable war against the Reds," it could be taken as evidence of Chiang's tenacious character, now put to better use against the Japanese. "This stubbornness," Snow argued, "is in fact one of Chiang's qualifies that make the Chinese Communists respect and support him today," expecting that he "can be made to fight" with equal determination against the Japanese. (In a Post article at this time, Snow stressed that Chiang had "faithfully adhere[d] to his united front pact" with the Reds.) With adroitness Snow concluded that the "objective conditions which are the instrument of Chiang's fate today are relatively dynamic and progressive, and it is because he continues to reflect their nature that his leadership remains secure."

In another piece on Chiang, over two years later, Snow pursued much the same line of reasoning, but by now raising warning signals for the future. He pointedly declared that the Nationalist leader "must soon either undergo a further transformation with the period or dwindle to a figure of relative insignificance." Chiang could retain his role as "the Leader by common consent only as long as he continues to symbolize the united national struggle against imperialism," and he would "lose his prestige overnight if he were to betray that trust," he asserted. Snow, however, was still ready to applaud the Generalissimo's "steadfastness" under that test, which "has helped to stamp China's fight for independence with the dignity of one of the heroic causes of our time." On the proposition that a man can be judged only against "the milieu and limitations" of his own time and place, Snow finally pronounced, "it seems likely that, despite his prejudices and contradictions and counter-revolutionary past Chiang Kai-shek will be remembered as a great leader." But, Snow emphasized, citing views he attributed to the Communists, the broader "the revolutionary mobilization of the masses," the "deeper would become the revolutionary mission of the war—and the more revolutionary a leader Chiang would be forced to become, if he wished to hold his place at `the center of resistance.'"

It was equally evident that, for Snow, CIC itself was a crucial element in the military and political dynamics of the China equation. In a Post piece in the spring of 1940, in which he appraised China's protracted resistance effort both positively and optimistically, the Indusco story was in

the forefront of this relatively sanguine picture. "I believe," he ended, that "a better nation" will emerge from "the valley of slaughter" than the one that entered it. This article even elicited a warmly commendatory letter from Chungking's vice-minister of information (and Missouri journalism alumnus), Hollington ("Holly") K. Tong. "I do not hesitate to say," Tong wrote Ed of his "fine article," that "it is one of the best analysis [sic] I have seen of the present situation between China and Japan."[26]

Snow's public flirtation With the notion that the Generalissimo and his government could or would rise to the occasion of a popular revolutionary-style war effort had run its course by the end of 1940. With the unraveling of the united front and growing possibilities of renewed civil war, coupled with the correspondingly deteriorating situation of CIC, Snow's misgivings would be more openly expressed in his published views. In his personal opinions, as previously noted, Snow from 1937 on continuously took a much more pessimistic and skeptical view of Chiang's wartime stewardship. In this vein, in a letter to Jim Bertram in November 1938, shortly after the loss of Hankou to the Japanese, Snow acidly remarked that Chiang "will simply retire as far back as he is pushed, and it may be best for China that he is pushed to Tali or Bhamo [on the Burma frontier]. Certainly nothing can be done to organize the people, or to mobilize the resources of the hinterland, in areas he controls." Ed (and Helen) therefore saw CIC's primary mission to be one of sustaining the guerrilla-style war waged in the regions of Red military operations. Getting CIC support for "guerrilla industry" became a chief preoccupation of Snow's Indusco work. Though the Kuomintang areas might be the "physical base" of CIC, he told Alley in 1939, the "spiritual base and organizational base must be in guerrilla areas." As always, Snow was deeply influenced in these views by his intense compassion for and emotional attachment to the ordinary people of China and their lives. It is "the youth, the very young, and the farmers, the poor of China, the soldiers, the workers, the men and women, millions of them, who ask so little and give so much in return for it, that make China break your heart!" Snow entered in his diary at the time. The "picture of Chungking and the interior sounds so terribly hopeless from all angles," he added. "Why should it seem such a personal and psychological problem with me?" Perhaps, he pondered, the reason for his strong reaction to all this might be "a conflict between my desire to write the truth as I

see it and the loyalties which prevent me from writing that truth?"[27]

Beyond this, of course, was Snow's continuously reiterated thesis on popular mobilization as the key to Chinese victory. According to his rea-

soning, as the Nationalist armies retreated further into the western China hinterland, their withdrawal gave Japan the opportunity to consolidate control over and exploit the resources of its occupied territories. Only Communist-organized peasant resistance could thwart this outcome, thereby making Japan's China conquests "a costly and entirely profitless venture which may ultimately bring ruin and defeat," Snow wrote Harry Price in November 1938. It would be "a race against time," he told Bertram, "to see whether the Xi'ans [Reds] can mobilize and train and arm the people, in the areas penetrated by the Nips, faster than the enemy can." And CIC was precisely the instrument to provide the essential mobile industrial backup for that effort. As Snow summed it up to Richard Walsh over a year later, "if nothing is done to strengthen the economic basis of guerrilla resistance, China. will probably be lost until such time as the fortunes of the Japanese Empire suffer a reversal through major war elsewhere."[28]

In 1938 from Hankou Snow had sent Mao a letter describing the newly launched cooperative movement. The following year he made his second visit to the Red northwest to brief Mao on CIC and secure his personal endorsement. The Red leader told Snow he had fully supported the movement since receiving Ed's earlier letter. Mao especially emphasized to him that GIG "should devote first attention to the guerrilla areas." In a follow-up letter to Mao, Snow noted that "my own deepest dissatisfaction with C.I.C. is that it has failed, thus far, to give important help to guerrilla industry, although that is where the sympathies of nearly all its leaders lie." On his return from the northwest. Snow recommended to CIC's international committee in Hong Kong that it "devote all possible available funds" to develop cooperatives in. the guerrilla districts of the north. "Whereas industrial cooperatives are compelled to make all sorts of retreats and compromises to survive elsewhere, in the guerrilla areas alone they can enjoy the fullest co-operation of the government, the army, and the population."[29]

Ironically, as in the case of Red Star , Snow was taking a more leftist position, again evidently in accord with Mao's, than the prevailing Communist orthodoxy on just where the political and military center of gravity in the China conflict lay. This was illustrated in an exchange of letters in early 1939 between the Snows and Israel Epstein on the question of CIC priorities and the principal purposes of its international promotional and fund-raising work. Epstein, who had been brought up in Tianjin and had known the Snows in Peking, was an able young journalist in charge of publicity for the CIC's Hong Kong promotion corn-

mittee, organized by Ida Pruitt in February 1939. Epstein argued for the conventional left line on the Kuomintang-led united front. He had strong reservations about Peg's outspoken views in her correspondence, on CIC's primary mission to help Communist forces in the field. ("Our underlying aim [in starting Indusco]," Helen responded to Epstein, "has been and is now more than ever to make Indusco a medium of helping the people's movement in China, and of securing foreign funds for this in as great a percentage as possible.") As Epstein put it in a rejoinder to the Snows, "if we are not to come to grief, there must be thorough discussion of how Indusco can serve its ends with maximum effect and yet with maximum adherence to UF [united front].... The UF, not some ideal UF but the pulsating and writhing thing that exists at the moment and must be the inevitable environment of our work." Ed, with some asperity, wrote back: if "your committee does not intend to devote its main energies" to raising money for the guerrilla areas "you are evidently under a misapprehension concerning the purposes of the founders of the movement." Snow listed as a fundamental objective of CIC, "to provide indispensable economic bases for the military and political forces of the democratic people's united front"—a distinctly different concept from Epstein's "UF." "Our allies are CDL [Madame Sun's Hong Kong-based China Defence League] and Era and Newfa [the Communist Eighth-Route and New Fourth Armies]," Snow continued, "and not ML and HH [Madame Chiang and H. H. Kung]—whom we must encourage and help, of course, without however dissipating our own slender energies."[30]

Snow's formula for CIC—of working both with and around the Nationalist government—and essentially at political cross-purposes with it—surely had its own contradictory if not mutually exclusive character. (Ed himself seemed to acknowledge this in talking of "guerrindusco" as a discrete entity and undertaking.) For this formula to work at all called for financing and control largely independent of the Chinese government. This goal in turn required vigorous promotional and fund-raising efforts abroad, and the creation of influential externally based committees to flannel the monies raised, through Alley, straight to CIC in the field. As Snow bluntly framed this to Epstein, "I think there is no question that Alley can guarantee the use of all funds secured by us for use in guerrindusco if that is the will of the [Hong Kong promotion] Committee as it most certainly should be, in my opinion." At the inception of CIC in the summer of 1938, Snow had already indicated the semi-adversarial relationship with the Nationalist government he and his fellow Indusco

sponsors anticipated. "We may suffer rebuffs, we may be disowned," he had written Helen, "we may irritate and provoke the Gov., but there is no other way to make them act except to keep the movement going outside and push them along."[31]

Snow worked hard in the next months to help organize an international committee for CIC. Its first meeting was in July 1939, with the respected and social-minded Anglican bishop of Hong Kong, Ronald O. Hall, as its chair. Chen Hansheng (Han-seng), a noted agrarian specialist and acute observer of the China political scene whose links to the Communist movement became known later, was secretary of the committee until the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in December 1941. (Thereafter the committee was based in Chengdu in western China.) Snow was a member of its board of trustees and Alley held the post of field secretary under the committee, which had auxiliary status in Kung's central headquarters in Chungking. The committee had a continually uneasy, competitive relationship with Kung, who sought control over it and of the funds channeled through its hands. "It is fair to say," Alley wrote Ida Pruitt in August 1940, "that without foreign interest and help, the CIC would have been wrecked long ago."[32]

Ida Pruitt had gone on to the United States to organize promotional-funding work there. With branch committees operating in various cities, Indusco, Inc., American Committee in Aid of Chinese Industrial Cooperatives, was established in New York in September 1940. Eleanor Roosevelt headed its advisory board, Admiral Yarnell (now retired) chaired the board of directors, with many luminaries (including Pearl Buck and her publisher husband, Richard Walsh) on the board. CIC "was fast becoming a major (and easily romanticized) factor in American thinking on China." In a March 1939 letter to Madame Sun urging her to join the board of the impending Hong Kong international committee, Snow emphasized that through fund-raising efforts around the world, "It seems likely that ten million dollars could be got under the control of this Trustees Board in a year or two. If [the board] is correctly constituted, in its membership, two million at least—let's be very conservative—can go to the guerrilla industry in which we're most interested." Actually, through 1945, the international committee had disbursed an estimated total of five million dollars (U.S.) to CIC, raised through promotion committees abroad. The American committee for Indusco itself provided some $3.5 million for CIC up to the Communist takeover in 1949—1950.[33]

As to the extent of guerrindusco support, a CIC center was set up in Yan'an (initially sanctioned by Kung), following a visit there by Alley in

early 1939. Through 1941 (after which all such contributions apparently ceased), a total of some $1,500,000 in inflated Chinese currency—worth only a fraction of that in U.S. dollars—came to this office through CIC sources. Much of it came from fund-raising efforts by the Snows among the generally prosperous overseas Chinese business community in the Philippines. The latter were also the major source of funds to finance many highly useful CIC projects in areas of New Fourth Army operations. "In those days [in the Philippines] I thought nothing of asking Chinese millionaires for fifty thousand dollars or so for the Communist regions for Indusco work," Helen Snow later recalled.[34]

However, by far the major share of financing for the Yan'an-based CIC operation (especially after 1940) came from the border region government there, and the great majority of the Indusco cooperatives had been organized by the government before their incorporation under CIC. This reorganization had apparently been carried out as a result of Snow's visit to Yan'an in September 1939. "I told them," Snow wrote Ida Pruitt, "if they would reorganize and adopt the CIC constitution I'd try to get some help for new capital from IC [international committee]." Evidently in anticipation of such funding, Alley designated the Yan'an CIC an "International Center." While the Indusco example and experience may have influenced the pattern of the major production movement launched under Mao in the border region in the early 1940s, it much more directly reflected Mao's own "new democratic" concepts of a less "statist," more decentralized, village-based, mixed economy of household, cooperative, and small-scale private entrepreneurial production units. In a long letter to Alley, written just days before Pearl Harbor from his new home in Madison, Connecticut, Snow summed up the results of all their work on behalf of guerrindusco: "I often grow discouraged about the results of our own efforts through these years. Except for the little money we raised in the PI [Philippines] we haven't done anything for the guerrindusco people and I am ashamed." In America, Snow added, "never a cent has been earmarked" for guerrilla industry, and the international committee "never remits a cent itself from our funds." Perhaps reflecting these disappointing results, as well as the gem eral decline of CIC after 1941 as it slipped away from its founding ideals, purposes, and leadership, Chinese Communist leaders themselves came to have little regard for or confidence in CIC.[35]

In September 1938 the Snows left by ship from Hong Kong to Manila (with Helen's usual thirty-eight pieces of luggage), and from there by car to the "air conditioned" mountain resort of Baguio in northern

Luzon. They looked forward, in this mini-American setting, to an extended and much needed respite from their exhausting immersion in the China drama. The last three years, from the December 1935 student movement on, had been a period of particularly high intensity, physically and emotionally draining. "I feel so completely lousy," Ed had written Helen from Hong Kong, just weeks; before the two left for the Philippines. He had no appetite, had lost weight, and couldn't sleep in the summer heat, he told her. Helen herself was still recovering from her Yan'an-contracted dysentery. Baguio, at five thousand feet elevation, was an unexpected treat with its "pine clad hills and clear fresh crisp air," Snow recorded. "I had grown used to the China air so that I thought the smell was a chemical part of all air and a universal." The couple rented a four-room cottage at the country club, where Snow played a round of golf the next day. It all seemed a perfect recipe for recuperation. The food at the club was "marvelous: huckleberry, pie, hot rolls, baked beans, milk-fed chicken, American lettuce.... Everything is on the American scale." But they had not escaped world realities. A few days later came news of the Munich pact. "To me it appears to be the most cynical deal in human life and property ever made by a responsible self-respecting people to save its own neck," Ed bitterly noted of the roles of Britain and France. It was a reaction that would strongly color his thinking on the 1939 Soviet-German agreement and on the early stages of the European war.[36]

Snow had arranged for a leave of absence from the Herald and planned to concentrate on his new book about the China conflict. He also looked into the current situation in the Philippines, produced a few articles on the U.S.-Philippines relationship in the context of a threatening Japan, and thought he might quickly turn out a short book on the subject to help defray living expenses. As it turned out, there was no market in the United States for such a work, and as he (and Helen) became ever more deeply caught up in CIC affairs, his big book on the war had to be put aside until 1940. "We came here for a vacation but haven't stopped working for a single day," Helen complained to Hubert Liang after a few months in the islands.[37]

But most of this work brought them no income. They were soon thoroughly involved in committee-organizing and money-raising for CIC, principally among the Manila Chinese, but with much encouragement from the American political establishment there and valuable help from good friends they made in the American business community. It became one of the most successful of such overseas efforts on behalf of CIC, especially in support of the Snows' pet project, guerrindusco.

From the Philippines in 1940 they also drew up and orchestrated a petition to Roosevelt for a $50 million American loan for CIC. Sponsored by Indusco committees in the Philippines and the United States, the document was signed by an illustrious list of Americans. Snow pushed the idea in his first meeting with the apparently sympathetic president early in 1942. Roosevelt sidestepped these efforts on grounds of nonin-terference in Chinese domestic affairs. He did promise Snow he would personally put in a plug for CIC with the Generalissimo. "I suppose I should have told him that Chiang wasn't the man to take a hint; he had to be pushed," Snow ruefully related in Journey . Helen followed up Ed's visit with Roosevelt by sending the president a copy of her book on CIC. In writing the book, Helen wrote F. D. R. in her unsubtle "up front" style, "I had you back in my mind all the time as the great hope for trying to get some American support for the movement." Actually, the Snows' notion that the Chinese government could be effectively "pushed" on CIC through external pressure would turn out to be another less than successful example of foreign efforts to "change China."[38]

Ed and Helen operated as a behind-the-scenes guiding and coordinating center for promotional activities in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, in England and North America, and for CIC work in China. They clearly regarded the cooperatives as their offspring and were intent on keeping it on the path they had charted, and on guarding it against a hostile takeover from central headquarters in Chungking. They engaged in lengthy, and often frustrating correspondence exhorting, advising, and occasionally badgering those in charge of CIC work, principally Ida Pruitt in America and Alley in China. The Snows viewed both, in their separate spheres, as indispensable to the success or even survival of a relatively autonomous and "progressive" cooperative movement. If "you lose the independence of your Committee," Snow warned Pruitt confidentially, "your work loses its value to RA [Alley] and all the CIC people who are fighting to keep the organization out of the hands of the machine politicians." Alley, Snow continued, "can only be helped through the International Committee, which exists primarily for the purpose of backing up his leadership." There was always another crisis to manage, as well as personality problems to iron out and ruled feathers to soothe. "No more now, I've spent a whole day on this bloody business," Snow irritably concluded another letter to Pruitt, after a particularly heavy and exasperating day of correspondence on such CIC problems.[39]

Helen Snow carried on an even more massive CIC correspondence, which often tended to take on a "command" quality with long lists of

peremptory instructions. A few weeks after getting settled in Baguio, she sent Alley one of her missives. She launched into many pages of directions, under the heading, "Here is what must be done." For poor Alley, more than fully occupied in building the cooperatives from scratch, Helen ticked off a lengthy catalogue of promotional chores—letters, reports, and possible articles to write. Between Alley, the seat-of-the-pants, China-rooted builder, and the more politically focused Snows, differences in perspective were inevitable. "YOU HAVE GOT TO DO SOME PROMOTION WORK. Don't you know that 90% of getting started in China is political? PLEASE STOP WANDERING AROUND YOURSELF for a few days," she ordered, and write up "a full report" on the cooperatives. His "main job" was now organizational, she added. "Don't get lost in the mechanical details." (For Alley, of course, God was in the details.) Helen summed up her own standpoint: "The whole world needs fixing so badly that one hardly knows where to start or to stop."[40]

Snow made extended trips back to Hong Kong and China from the Baguio base, on CIC business and for his regular China work—both now closely related. He spent most of 1939 in Hong Kong and Chungking, and in journeying along the "Indusco line" to the pioneering and thriving northwestern CIC center of Baoji, from there on to Xi'an and Yan'an, and back to Chungking. The account of these Indusco travels., and of CIC generally, became a central feature of his Battle for Asia . Virtually all his China writing in that period either directly or indirectly aimed to publicize and win friends abroad for the cooperatives. In so doing he sought to preserve a "non-official" status in the movement, in part because he felt his Red Star- tainted reputation would not play well in Nationalist circles (though it was an asset to CIC elsewhere). But probably more important, Snow was concerned to maintain his non-affiliated professional journalist role. He was "very annoyed," he wrote Pruitt in June 1940, that some Chinese Information Service material from Washington referred to him as "a leader" of CIC. "I am only a committee member, no official connection, won't be able to do anything for CIC if this goes on," he added.[41]

But in truth, Snow was a leader at every stage of the CIC saga through 1941. Rewi Alley's later apt description of Ed as "standard bearer of Gung Ho" was closer to the reality than Snow's own disclaimers. What Snow's (and Helen's) nonofficial capacity did mean was that the enormous amount of effort, time, and expense put into their CIC work was uncompensated, with the exception of a few CIC-related articles Ed did

for the Post and other journals. "I have spent months of my time, and about all my surplus cash, working on this project," Snow wrote Ma Haide after his September 1939 Yan'an visit, which led to the creation of the international CIC center there. "We have spent all our money again, as usual," Helen told J. Edgar and Mildred, and by the time Ed got down to sustained work on his book in the spring of 1940 (again on leave from the Herald "sans pay"), he had "already spent most of the advance royalties, alas!" he wrote his father. In taking hours and days he could not afford to lose away from his book to do necessary CIC writing that summer, Snow reiterated his characteristic journalist philosophy. "I think it is our obligation to put in an oar on the side of decency when we can, if journalism is to retain any dignity or social usefulness," he wrote an editor. His involvement continued even after his return to the States. "I cannot run away from (CIC), as I long to," he wrote Richard Walsh in mid-1941. "I am too deeply committed to some fine people who have given up far more than my little time, and whose very lives are at stake. "[42]

Kewi Alley, as a partner in starting CIC and as Ed's personal choice to run the movement, was essential to the Snows' internationally based strategy for keeping the cooperatives on course and out of the wrong hands. ("If RA [Alley] goes, the whole show goes," Snow told Ida Pruitt.) Alley thus became the "star" in Snow's writings on Indusco. The idea was not simply to give this extraordinary man his due. To portray him as the inspirational embodiment of all that CIC stood for was an effective way to rally international support and, it was thought, give Alley the clout he needed for the inevitable infighting over CIC control in China. It would thus be difficult for Chungking to discard him entirely without stirring up an adverse reaction among friends of China abroad—a result that would dry up aid funds not only for CIC but for other China causes as well. "The only thing that is now preserving CIC's leadership from wholesale liquidation [by Chungking] ... is fear of American and to a lesser extent of [other] foreign opinion," Snow explained to Walsh, then chair of the American Indusco board. By personalizing the CIC story through Alley, Snow contributed significantly to shaping that opinion.[43]

"There is one hero in particular, Rewi Alley," Snow wrote Random House of work in progress on his Battle for Asia . Alley's effort to build guerrilla industry in China, Ed went on in an overblown comparison, was "as much of an epic as Lawrence's organization of guerrilla war in Arabia," and it provided "a kind of ribbon of hope" for the latter part of

his book. But probably Snow's single most influential writing on Alley and CIC was his Post article in early 1941 (a version of material included in his book) called "China's Blitzbuilder, Rewi Alley." It was a deserved paean of praise. and admiration for Alley but also an extravagant picture of CIC's achievements and potentialities at a time when the prospects in China, both for Alley and Indusco, were already quite bleak. Who can say, Snow concluded, that in the end Alleys achievement may nor "prove of more lasting benefit to mankind than the current battles for empire," and be "the most constructive result of the battle for Asia itself?" But such publicity did have its effect. Since mid-1941, Alley later recounted, "foreign contributions [to CIC] had taken a quantum leap," in part because of the "publicity about me and Gung Ho, especially in a Saturday Evening Post article by Edgar Snow." But Kung's central headquarters also redou-bled its efforts to gain control over these new funds.[44]

In writing for the mass American readership of the Post , Snow dwelt much on Alley's unique foreigner role in China, a point Rewi himself liked to downplay. "Never before, I believe, had a foreigner been given such wide responsibility," Ed declared, "for the actual organization of a socio-economic movement in China." Alley's decidedly non-Chinese appearance was made to order for Snow. With his "fiery hair and hawk-like English nose," Alley was the perfect image of "the kind of foreign devil to frighten the wits out of Chinese children."[45]

Alley was truly excellent material for Snow's promotional endeavors. A twice-wounded decorated hero of the western front in World War I, he had struggled for a bare livelihood in sheep farming in New Zealand before coming to Shanghai in 1927. He already had, in Douglas Reynolds' words, "an instinctive antipathy for the idle rich, and a natural sympathy for the struggling and disdained poor." His China revolutionary sympathies were galvanized by the miserable working and living conditions he tried to correct, as factory inspector in Shanghai. Alley's radical politics came directly out of his compassionate but hardheaded humanity expressed in unfailing respect for those who were poorest and most disadvantaged, especially the young. The China scholar Olga Lang, who accompanied Alley on an inspection tour of Shanghai facto-tics and workshops in 1936, recalled that the young boys and girls who worked in them "greeted Rewi as they would a friend and protector," as "an uncle and father." She was particularly impressed that Alley checked the children for signs of vitamin-deficiency beriberi disease by pressing their skin "without any trace of fastidiousness .... These were his own boys, not the objects of charity, not 'the poor heathens' whom one has

to help out of some abstract moral [or, we might add, political] considerations."[46]

For Indusco, Alley exhibited a similar mode of on-the-spot personal contact with individual cooperatives and their members throughout the country. By 1941 he had logged tens of thousands of miles, "investigating Indusco in the field, creating it, and mothering and fathering it," in Snow's words. The American writer Graham Peck, who worked with CIC for a time and accompanied Alley to the CIC center at Baoji, related that "as soon as word spread that [Alley] had arrived, Co-op workmen, organizers, and administrators [each with a "special grievance or problem"] poured in to see him from dawn to bedtime." Alley was constantly on the go in his familiar khaki shorts, traveling by wheezing charcoal-fueled truck or bus jammed with every variety of passenger and baggage, by boat, bicycle, or more often than not trudging on his powerful trunk-like legs over the usually roadless interior. Cheerfully he shared and even savored the privations of everyday Chinese life and travel, stoically endured danger and disease, and seemed indomitable and indestructible. "This is my 20th day sick," he wrote Pruitt from a southeastern hinterland CIC base in June 1939, of a severe typhoid attack. "Do hope that other truck comes up so that I can bag it" for the northwest. On virtually all such trips Alley was but one of many hitchhiking ("yellow fish") passengers. "It was a crowded vehicle indeed that Evans Carlson [who was with him on a 1940 CIC trip] and I crawled into in Kanchow the other day," Alley reported. "I went in through the window, as that seemed the quickest and most popular way. Evans being tall, hit his head frequently as he wormed himself over the piles of luggage in the centre of the bus floor." Carlson (who had these same qualifies himself) wrote the Snows, "There is a spiritual quality about Rewi which triumphs over disease, fatigue, or any other element which might be expected to leave a mark on him. He is truly one of the anointed."[47]

Whereas Snow was intent on building Alley's international reputation, Rewi himself preferred a less conspicuous role. He was inclined to understatement as opposed to the grand claims made for CIC and himself by its proponents abroad, including Snow. He adapted himself naturally to his Chinese surroundings, spoke fluent and pithily colloquial Chinese, and could regale his peasant-worker Indusco audiences with amusing and self-deprecating anecdotes on such outlandish foreign things as his extremely prominent nose. As he told Graham Peck, "the easiest way to get along with people who are suspicious of foreigners was to make the state of being a foreigner seem ridiculous." While the

Snows and others bemoaned the fact that Alley failed to exploit his international prestige ("face" in Chinese terms) in the political and bureaucratic infighting in Chungking, Alley instinctively understood the pitfalls this involved for him, not only as a foreigner, but as a suspected CCP sympathizer. He concentrated instead on trying to make things work—both people and machines, at the grass roots.[48]

This focus became a source of some contention between Alley and Snow. Ed placed much more weight on the political and foreign publicity aspects of the CIC operation. Rewi put his faith primarily in a "demonstration in the field that will 'save' CIC in spite of opposition," Snow commented in his diary of an inconclusive discussion with Alley in Hong Kong in mid-1939. Alley "thinks he can get to 10,000 [co-ops] on present basis. I tell him we are building the movement in areas of political insecurity." Alley thought Ed greatly overestimated his ability directly to influence matters in central headquarters. "No use to say that I should have stayed in Chungking," he wrote from Jiangxi in June 1939. "Our own H.Q. very certainly did not want me there. And nothing would have happened in these regional H.Q. unless we had got out on the job." Snow had earlier written Pruitt that Alley's position in Chungking was "fundamentally very strong if he uses it but trouble is he's no good at [the] political wire-pulling and intrigue" essential to holding his own in "the rotten system" he was obliged to work with. All the more reason, Ed added in the Snows' familiar and continuous theme, "to strengthen Rewi's prestige abroad, and thereby in the Government." Alley must not "get lost in field work," Helen wrote Ed that May. He was expending all his energy, she complained, "walking around the country and setting up factories with his bare hands." Chen Hansheng put the issue succinctly, in the wake of a major "reorganization" of CIC by Chungking in 1940. "Rewi thinks that if we could build up a strong field force with good coops we will be all right," he told Helen. "I hold a different opinion because I think good coops are eggs of the hen, which, however, now approaches non-fertility."[49]

There was in fact much merit in both positions. Without the organizing, publicity, and fired raising pushed by the Snows, CIC would very likely have withered on the vine early on, and without Alley's total hands-on commitment to the building process, the remarkable achievements of the early CIC years would equally have been impossible. Each side recognized and appreciated the other's contribution. But both had their illusions: Alley that he could safeguard the movement's vigor, purposes, and integrity in the field, and Snow that Alley's continued ability

to do so would depend to a good degree on international publicity-derived political capital Rewi could draw on in Chungking.

Ed's position reflected the pronounced foreign vantage point of Indusco, sometimes narrowed to the personal responsibility of the two Snows. "If it becomes impossible to cooperate with Chungking," Ed declared to Pruitt in early 1939, "we will continue it as a purely Era and Newfa responsibility, and for it can tap the same sources of [outside] help." Helen carried this idea a step further in her own letter to Pruitt. If Alley was "kicked out" by Chungking, CIC should not only operate "independently" of the government, but start a campaign to replace Kung by the more CIC-friendly T. V. Soong. "Rewi thinks the way to work with the Chinese," she followed this up to Pruitt, "is to give them the open control and do all the hard work himself." But the Chinese would probably interpret this "as being weak-kneed, especially from a foreigner." The key to influencing Chungking was "foreign approbation," she told Ed. Snow, reacting to CIC's recurrent reorganizational crises, urged Alley in August 1940 to take the lead in developing Western-style democratic mechanisms for shifting power from bureaucrats at the top to the co-op members themselves. He outlined an ascending system of elective bodies from village-level co-op units to a central council at the apex. This council, he declared, should eventually acquire "by whatever methods necessary, the right to approve and finally actually to appoint its own central administration." The people now in charge in Chungking, he pressed on, "must be made to represent the common will of the C.I.C. masses. If you do not recognize that," he admonished Alley, "you will simply be deceiving yourself and evading the responsibility—which is now historic—that a combination of circumstances has put upon you." Just how Alley was to accomplish this takeover from below, in the context of a repressively authoritarian and hostile regime at the head and a traditionalist society at the base, remained unclear.

In any event Alley's way was typically Chinese. In his view, the further away from central headquarters and the less direct contact between it and units in the field, the better. Out in the hinterland, "due to bad communications, one could get progressive administrators appointed more easily," he later explained. But rather contradictorily, he acknowledged that "Gung Ho also suffered many raids and arrests in various hinterland centers throughout 1941-44." Perhaps Alley came closer to the realities in cryptically pinpointing CIC's key problem to Graham Peck in 1941: "We're trying to do it at the wrong time. We are a thousand years too early for the officials and a thousand years too late for the

people." The notion of externally "moving" China forward was bluntly put by Helen Snow in her CIC book. "All that [China] needs is a good push from behind." She always identified CIC with her own Anglo-American Protestant ethos, and (with an intent also on garnering American support) underscored the Christian faith and American nurturing of Alley's Bailie Boy lieutenants. "They are the most Americanized Chi-nest one could imagine," she asserted in her book. "They like American slang and American food and American clothes and American methods."[50]

This Western coloration and reformist-interventionist attitude predictably annoyed conservative Chinese nationalist sensibilities. It gave a semblance of plausibility to the "imperialist" allegations raised in hostile Chinese quarters that added to the threateningly radical image they held of the cooperatives. Alley could thus be painted both Red and imperialist, and Snow found himself labeled a British agent (presumably for his ties to Clark-Kerr) in the gossip of Chungking. (Snow later used the term "missionary"—which had its own Western intrusionist connotations—as best describing his own and Alley's CIC roles.) CIC was similarly accused of facilitating inroads by foreign capital into China. Nor did Alley's Snow-promoted international standing protect him from eventual dismissal as technical adviser by the executive Yuan in September 1942. On the contrary, as Rewi later wrote a CIC colleague, "the starring of my poor efforts have done me a good deal of harm with political people in CK [Chungking]."[51]

Though Alley remained field secretary under the international committee, his title came to have little meaning in terms of overall responsibilities or control of monies. The committee itself, and Indusco's parent funding organization in the United States (United China Relief), increasingly gravitated into the orbit of Chungking. By 1945 Alley was hunkered down in the remote community of Shandan in the far northwestern province of Gansu on the edge of the Turkestan desert. There, he and a resolutely idealistic young Englishman, George Hogg, had built up a Bailie-type work-study center, enrolling peasant youths from this impoverished area. Hogg tragically died in 1945 of tetanus from an infected stubbed toe, and no vaccine available to save him. The Shandan enterprise, under Alley's direct management after Hogg's death, was a perfect example of the style Rewi always found most comfortable and satisfying: personally involved, youth-centered, away from the political spotlight. He had now, as he later recounted, "shifted my attention to training technicians at the Bailie schools to help build a New China

which I felt was surely to come." The Shandan school, with help from "progressive forces" abroad, reached a maximum of some four hundred students, with a thriving complex of technical workshops, educational, medical and agricultural facilities. It seemed to embody and demonstrate in microcosm the faith affirmed by Bailie, Alley, and Snow in the mostly untapped potentialities of China's poorest peasant millions.[52]

CIC itself, facing a mounting combination of political-administrative, economic, and financial problems, declined steadily after 1940. Its downward spiral leveled off by 1945 at a total of somewhat over three hundred co-ops, where it more or less remained until Communist victory in 1949. Meanwhile Alley and his school, harassed by government agents, local militarists, and gangsters, ardently and expectantly awaited the arrival of the forces of revolutionary liberation. Ironically, however, the "struggle" tactics of Communist cadres proved no less meddlesome than the takeover methods of Kuomintang bosses. One such "political work" cadre assigned to Shandan by the new regime "set about very steadily to destroy the foundation of the school," Alley much later disclosed. "It was utterly crazy to try to undermine the good boys and say they were all gangsters and to promote the useless ones and send them off to relatively cozy jobs." The school was taken over by the Beijing government's ministry of fuel, Alley's training program for small village industry was "shelved," and Shandan's activities were shifted to the Gansu provincial capital of Lanzhou by 1952. There it concentrated on training technicians for the modern state-run oil industry. All of this was the antithesis of the autonomous, decentralized, small unit, rural-based cooperative network CIC's founders had envisioned. Symbolically, virtually all the buildings of the original Shandan school were destroyed in an earthquake at about that time. CIC was formally terminated by Beijing in 1951, not least for the international ("imperialist") links that Snow had so painstakingly worked to create specifically to ensure CIC aid to Red-controlled areas. CIC was simply "knocked out," Alley told me. The Communists said "it was just an imperialist dodge to get into China."[53]

Thus in the end Indusco became yet another frustrated Western "reformist" attempt to remake China. In many respects CIC was a wartime follow-up of earlier efforts at rural uplift during the prewar decade, in which American Protestant missionaries and their Chinese associates played a large part. The activities of Joseph Bailie prior to that, his later influence on Alley, and the role of his Bailie Boys in Indusco, further underlined these continuities. (In 1933 Snow himself wrote very favorably

of the achievements of the widely acclaimed and influential model county project of Tinghsien [Dingxian], in northern China, initiated bit James Y. C. Yen, the renowned American-educated former YMCA secretary and initiator of the rural-oriented mass education movement.) As recounted in a study by James C. Thomson, these prewar reformers also) faced the daunting challenges posed by their "overly close association" with a government that "stood firmly in defense of the old social order." In terms equally applicable to the Indusco experience, Thomson notes "the grandiose aims and the inadequate instruments possessed by the Americans who attempted to influence the development of modern China in the Nanking [1928-1937] years." Even by those days, "gradual-ism had been outstripped by the Chinese revolution." Thomson cites one of the Chinese Christian reformers of that era, Y. T. Wu, who stayed on under the Communist regime after 1949. In a mea culpa on his American-linked reformist past, Wu declared in 1951, "All of us have been the tools of American cultural aggression [imperialism] perhaps without being wholly conscious of it." It was, evidently, the CCP's final verdict as well on the Indusco enterprise.[54]