PART I—

THE MONARCHY

On a mid-December morning in 1800, don Martín Sánchez Tomé, a notary of his majesty in the city of Salamanca, rode north out the Zamora gate, bearing a written order issued by don Manuel Ortiz Pinedo, alcalde mayor of the city. With him was a constable (alguacil ordinario ), to provide him aid if needed. The road toward Zamora took them over a slight rise, from which they could observe a gently rolling countryside dotted with small villages but otherwise virtually unobstructed as far as the eye could see. The plain of La Armuña was one of the richest grain regions of the Castilian meseta, and in spring half the land would be tilled and the wheat would grow up lush and green. But now in the wintery light the scene was not encouraging to the two men, for all the fields were lying fallow and the rich, red earth was showing through its covering of stubble and weeds. Oxen, mules, donkeys, and sheep pastured here and there, kept from wandering by their herdsmen.

After the pair had traveled some two leagues along the road, they turned off toward one of the smaller villages. It sat atop a low rise, a covey of mean houses huddled under the protective presence of their firm granite church. La Mata de Armuña, despite its small size, was a lugar, with its own officials; two of them, the "petty mayor" (alcalde pedáneo ) and the keeper of the records (fiel de fechos ), were expecting the visitors. With them was one of the leading figures of the community, a forceful man along in years named Francisco González.

Once the order of the alcalde mayor had been presented and read, the men set off into the fields, followed by a group of curious villagers of all

ages, eager to witness a scene that had been enacted several times since the previous summer but that still broke their monotony with the mystique of royal agents from the provincial capital. The group stopped beside one of the hundreds of small plots into which the open fields around the village were divided. The notary read from the order a description of the plot, two acres (huebras ) more or less, bordered on the east by the road from Salamanca to the village of Narros, on the north and west by lands of the hospital of Salamanca, and on the south by a field of the village church. The plot in question was now to change hands, and the order instructed the notary to deliver it to its new owners. The tenants, the document stated, would have to vacate it in three days or, if allowed to remain, must pay their rent to the new owners from the date of transfer.

The order was the result of an event that had taken place in Salamanca on the previous Sunday. At eleven o'clock that morning in the hall of the royal jail of Salamanca, "the usual place for such acts," the alcalde mayor don Manuel Ortiz had met with the notary don Martín Sánchez Tomé and an alguacil to complete the auction of seven plots of arable land in the towns of La Mata and Narros belonging to a confraternity in Salamanca, pursuant to recent royal orders to sell the properties of such religious foundations to the highest bidder and deposit the resulting capital in the Royal Amortization Fund. Don Manuel ordered the public crier, who acted as auctioneer, to announce the last written offer for the plots and open the final bidding. The crier did as told, in a voice that rang through the hall, saying, "The bid has been raised to eleven thousand eight hundred eight reales. Match this last bid! . . . I perceive the closing, soon! . . . Soon!" He waited a few minutes, then intoned his cry again, and once more. No one in the audience responded to his encouragement. One final time the alcalde mayor ordered the crier to announce the auction, to no avail. After a suitable delay, he instructed the crier to award the sale to the authors of the previous bid, wishing them "Good fortune!" (

Sánchez Tomé took Francisco González by the hand, "in his name and that of his partner Marcos González," and led him into the plot. Francisco walked around its boundaries, kicked a few clods, ordered everyone out of it, "and took several other actions as evidence of the ownership that he assumed . . . quietly and peacefully without opposi-

tion from anyone." The traditional Castilian rite for the transfer of real property had now been performed. The notary said that it applied "in voice and name" to the other six plots included in the sale; even had the purchasers wished, the midwinter light would not have lasted for a visit to all of them. Before leaving, Sánchez Tomé recorded the names of various witnesses, including the keeper of the village records, a local linen weaver, "and many other persons who attended this ceremony."[1]

This scene is representative of thousands of others enacted throughout Spain in the last decade of the old regime. The government of Carlos IV, crushed by the expenses of war and fearful of a catastrophic bankruptcy, in 1798 ordered the sale of the property held in entail by charitable institutions and other religious endowments in order to appropriate the proceeds for its own needs. It thereby introduced one of the most significant developments in modern Spanish history, the abolition of entail and the forced sale at auction of church properties and many public properties as well. In 1800 most Spanish real estate could not be freely transferred on the market; a hundred years later the opposite was the case. In the intervening century, thousands upon thousands of buildings and hundreds of thousands of fields changed hands. The process, known in Spanish as desamortización, affected the way in which Spanish cities developed and the structure of rural society evolved. It involved the basic relationships between church and state and became central to the conflicts between Spanish liberals and conservatives in the nineteenth century, and it has been blamed for many of the country's contemporary social and economic ills.

The first of the great waves of disentail swept over Spain between 1798 and 1808. This was the ominous final decade of the old regime, which led up to the Napoleonic invasion, and the introduction of desamortización belongs to the agony of the absolute monarchy. Its authors, however, were responding not only to the tensions that emanated from the French Revolution but to the optimistic enlightened rationalism of the reign of Carlos III in which they had been reared. They believed that freeing rural property would improve agriculture and reform society.

In this book, the disentail will appear as the culminating act of the absolute monarchy, not the introduction of an age to come. This is a study of royal domestic policy and rural society in the second half of the eighteenth century, how they evolved and how they interacted. The bu-

[1] AHPS, Sección Notarial, legajo 3844, ff. 40v–44v.

reaucracy of enlightened Spain, inspired by a dedication to improvement, left to posterity impressive sets of records that make it possible to look in depth at the rural world at the end of the old regime. They include the first full population censuses of Spain, the famous survey of real property and economic activities in Castile at midcentury known as the catastro (cadaster) of the Marqués de la Ensenada, and memoirs on conditions in the countryside and proposals for agrarian reform authored or inspired by Carlos III's ministers.

The first part of the study looks at the country as a whole, focusing on the impact of demographic expansion and the response of the royal government. Spurred on by urban riots in 1766, the king's counselors sought ways to provide more food for the cities. The information they had and their own reason told them that the solution was to multiply the small farmers and restrict the power and privileges of the large landowners. Even during the wars of the French Revolution, the royal government strove to fulfill this program. Disentail was the most dramatic measure, seeking now fiscal salvation as well as rural reform. We shall look at how it was carried out and how much property changed ownership throughout the country. We shall see, too, how all the royal efforts were no match for the forces of nature and war that beset the state. When Napoleon's armies occupied Spain in 1808, neither horses nor men could have put the absolute monarchy together again.

The second part of the book turns to the rural scene and looks in detail at the structure of seven towns in the mid-eighteenth century and their evolution up to the Napoleonic invasion. (La Mata will be one of them.) We shall observe who owned the land, who worked it and how the town income was distributed locally and to the outside world, who lived well and who scraped by and how many there were of each kind. Rural population was growing, and the towns had to cope with the threat of declining per capita income. In one way or another all seven were responding to the rising demand for agricultural products quite independently of any royal planning. Pressures for change were wearing away the prevailing structures, and Carlos IV's orders to sell ecclesiastical property opened the gates to accelerated change. The results would be molded by local conditions and forces in ways that the planners did not fully anticipate. Francisco González, who took over ownership of the plot in La Mata, was new to farming. The disentail permitted him to use his savings gained elsewhere, as a muleteer perhaps, to become one of the leading farmers in the village.

The third part looks at the provinces in which the seven towns were located, Salamanca in the northwest of the Castilian meseta and Jaén in Andalusia. By enlarging the field of vision, we can identify other features of the rural world. A comparison of geographic regions within each province gives an idea of the extent to which economic development depended on topography, communications, and royal or seigneurial jurisdiction. An analysis of the people who bought property in the disentail and the kinds of land they preferred tells much about provincial society and the changes taking place in it. We shall form an image of the provincial elites, those men and women who provided the hinge between the rural people who drew their sustenance directly from the soil and the outside world of royal government and national markets, what their objectives were and how their pursuit of them influenced the general development.

When the picture is complete, it will embrace the motives and actions of government and individuals at the national, regional, and local levels—a broad but concrete study of state, economy, and society that observes the complex ways in which royal policies were decided and carried out and how their effects were felt throughout the rural world as well as the role of impersonal forces like demographic growth and the market for agricultural products. A final chapter will attempt to interpret the findings and set them against contemporary developments abroad and the later stages of desamortización in Spain. Thus a study of court and country in the enlightened reign of Carlos III and the troubled one of his son should enlarge our understanding of what was involved in the passage from the old regime to contemporary times in Spain, and not only in Spain.

Chapter I—

Agrarian Conditions and Agrarian Reform in Eighteenth-Century Spain

Until recently agriculture has been Spain's main domestic economic activity, and agrarian policy has always been an issue of major concern to its governments. Nevertheless, they did not take up the idea of a planned redistribution of land until the second half of the eighteenth century, when changing conditions forced the royal advisers to envisage the relationship between the countryside and the country as a whole in a new way.

During the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century, their main domestic concern was to increase the king's revenue. Their attention focused on the unequal weight of taxation borne by the different regions and social classes. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the people of Castile contributed far more heavily to the revenue of the monarchy than those of Aragon or Portugal. The Conde-Duque de Olivares under Felipe IV and Josef Patiño under Felipe V sought to equalize taxes and military service among the various realms that formed peninsular Spain. Olivares's attempts led to a revolt of Catalonia and the secession of Portugal from the Spanish crown, but Felipe V succeeded after the War of the Spanish Succession in imposing direct taxes on the realms of the crown of Aragon in place of the niggardly subsidies formerly voted by their cortes. The new taxes, called equivalente in Valencia, catastro in Catalonia, and real contribución in Aragon, represented a fixed percentage of the income from land and occupations.

Land belonging to nobles as well as commoners and land acquired in the future by the church was subject to the new impositions.[1]

The new taxes on the eastern kingdoms embodied the principle that everyone should contribute equitably to the needs of the state. For half a century after the reforms in Aragon, the search for a further redistribution of levies held the attention of royal policy makers. Felipe V and Fernando VI struggled with the church to establish their right to tax ecclesiastical properties, finally obtaining papal recognition of it in the Concordat of 1753.[2] The kingdom of Castile posed a different kind of problem. Here the major royal taxes, the rentas provinciales, weighed heavily on the poor, and their complexity meant that the expenses of collection absorbed an inordinate part of the proceeds.[3] The new system in the eastern realms proved so successful, especially in Catalonia, that Felipe V's advisers recommended that Castile's system be replaced by a similar one based on a single tax. The única contribución would be divided between a "real" sector that taxed income from property and a "personal" sector that taxed income from labor, professions, and commerce. The real property tax would be proportional to the income from land and buildings and be paid equally by nobles and commoners. As in Catalonia, a prior survey, or catastro, of property and personal income would be needed.[4] The aim was to establish a less regressive tax structure as well as a more efficient one.

In 1746 Fernando VI, on the urging of his secretary of hacienda (finance), the Marqués de la Ensenada, ordered an experimental survey in the province of Guadalajara, using the Catalan catastro as a model. It showed that a 7- or 8-percent tax on income from land of commoners and nobles and on commoners' personal income would produce the same amount as current taxes at less cost to the state. If the real property of the church were included, the tax could be reduced to 5 percent.[5]

In 1749 Ensenada obtained a royal order to extend the catastral survey to the other twenty-one provinces of Castile. To carry it out, the king established the office of provincial intendant. Intendants had been created in 1718 on the model of the French officials of this name, but they had soon been discontinued. The order of 1749 was the origin of a

[1] Matilla, Única contribución, 29–41; Kamen, War of Succession, 335–37, 359–60.

[2] Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 13.

[3] Ibid., 97, 110. Ozanam, "Notas," 52, says the cost of collecting all royal revenues in Spain was 11.2 percent of the gross income in 1751–60. The rate for the rentas provinciales must have been much higher. They represented 32.8 percent of net income.

[4] Matilla, Única contribución, 43–51.

[5] Ibid., 53–55.

new, permanent set of royal servants who were to become the key figures in the provincial administration of the kingdom.[6] The intendants began the survey in 1750, setting about obtaining a full list of the properties and sources of personal income in all the cities, towns, and villages of Castile. By 1756 they had completed all twenty-two provinces.[7] The result is commonly known as the catastro of the Marqués de la Ensenada.

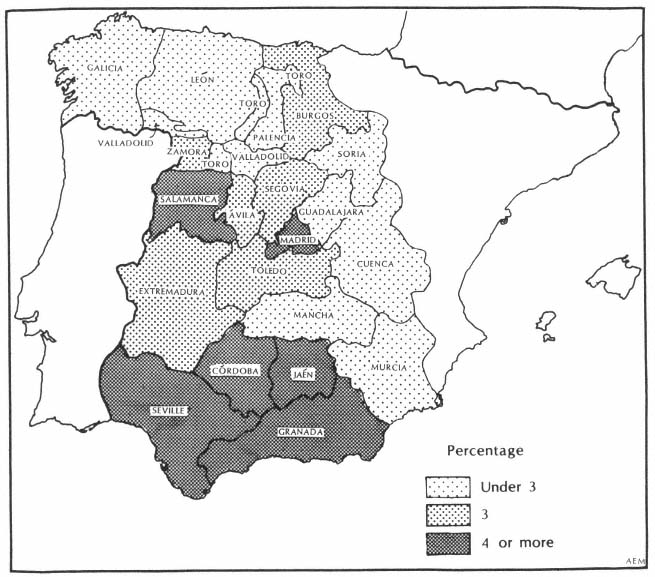

The returns revealed how unfair the existing tax system was. The income from the property of the church represented 19 percent of the total income from real property in Castile, but the subsidio it paid annually to the crown was equal to only 3.6 percent of the rentas provinciales collected from the rest of the population.[8] According to the information collected, an equitable single tax of 4 percent on income from all sources would produce as much as all existing taxes. Such a reform would obviously benefit the poor, while the religious orders, secular clergy enjoying benefices, and wealthy nobles would lose some of their privileged status.

Although Fernando VI approved the single tax in 1757, it never went into effect. Ensenada had been dismissed in 1754, and Fernando became despondent and nearly insane after the death of his queen in 1758, succumbing himself a year later. His successor, Carlos III, and the new minister of hacienda, the Marqués de Esquilache, took up the matter, but they lost time by ordering the towns to review their original surveys and bring them up to date. Now fully aware of the significance of their returns, the petty municipal oligarchies dragged their feet, raising malicious questions and delaying their responses.[9] The reassessment took four years, and when it was done, the towns had discovered that their incomes were far lower than those stated in the original surveys. Two years later riots in Madrid and many other places drove Esquilache from power and marked a major turning point in plans for reform. Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, a fiscal, or advisory attorney, of the Council of Castile, became the most influential adviser in economic matters, and he had serious doubts about the practicality of the única contribución in regions whose agricultural economy was not mone-

[6] Ibid., 63, 87–88; Desdevises, L'Espagne 2 : 134–37.

[7] Matilla, Única contribución, 92.

[8] For value of ecclesiastical property and all property in Castile according to the catastro, see Table 5.5. The figures for the ecclesiastical subsidio and the rentas provinciales are in Matilla, Única contribución, 93.

[9] Otazu, Reforma fiscal, 145–76. Otazu provides the full story of the única contribución in Extremadura.

tized.[10] Still, a royal junta continued to discuss the single tax for another decade. In 1770 Carlos III ordered it put into effect as soon as provincial quotas could be assigned. Six years later this had still not been done, and the matter was dropped.[11]

All the work was not in vain, however. The idea of replacing the rentas provinciales by a single tax on income remained to inspire later ministers[12] and became the basis for a sweeping revision in 1845.[13] Meanwhile, the thousands of volumes of the catastro of Ensenada containing detailed information on the ownership of property throughout Castile were stored in the offices of the intendants, ready at a moment's notice to reveal the entailed estates of the church and the nobility. They are today one of the most remarkable sources anywhere of information on the society and economy of a preindustrial state.

2

In the 1760s a new worry drew attention away from the need for tax reform: the apparent disparity between the increasing food requirements of the country and the harvests from its soil. In recent decades historical scholarship has devoted much attention to the relation between the supply of food and population levels in early modern European countries. As a general rule, the prices of basic foodstuffs like wheat or other grains were far more elastic than those of nonagricultural goods. Europe as a whole in the early modern period followed a short fallow system, the two- or three-field rotation of grains, pulses, and fallow familiar to historians. Ester Boserup has shown that this system of cultivation is particularly susceptible to bad harvests.[14] The resulting impact of famines on real incomes directly affected demographic trends. In the extreme situation a bad harvest would cause the price of bread to rise precipitously, and many people would be unable to buy the food they needed to survive.

Two common demographic responses to declining per capita food supplies can be related to Malthus's identification of "preventive" and "positive" checks to the growth of population. In the "preventive" case, a rise in food prices resulting in lower real incomes discourages mar-

[10] Llombart, "A propósito."

[11] Matilla, Única contribución, 96–100, 107, 123–24.

[12] See Cabarrús, Cartas, 349.

[13] See Estapé, Reforma tributaria.

[14] Boserup, Conditions, 48–49.

riage and thus induces a decline in fertility. Although the resulting demographic response is sluggish, it nevertheless preserves a relatively high standard of living for a preindustrial society. A "positive" check, on the other hand, exists among populations that live close to the margin of subsistence, whose lower classes suffer a constant condition of malnutrition. Here a disastrous grain harvest or, worse, a series of bad harvests will cause the weakest members of the society to die off, victims of starvation or diseases that attack the debilitated society. In their impressive history of English population, E. A. Wrigley and Roger Schofield have labeled these two demographic responses respectively a "low-pressure system" and a "high-pressure system." As per capita food supplies decline in a high-pressure system, increased mortality lowers the level of population, while in a low-pressure system reduced fertility keeps the population from straining the subsistence resources except in unusual circumstances.[15]

According to these two authors, England enjoyed a low-pressure system from the early seventeenth century to the industrial revolution, with the consequence that it was socially and economically better prepared than continental Europe to take advantage of technological innovations. From the evidence that has been produced by historical demographers who have looked at France, Wrigley and Schofield conclude that during most of the old regime this country approached a high-pressure system. Present information indicates that France suffered severe crises of mortality in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, usually associated with poor harvests, although a recurrence of the plague and the ravages of war also played important parts in these catastrophes.[16] We still do not know if the severity of these crises reflected a society that was less prudent than England's in making decisions to marry, or if the famines were extraordinary events that resulted from a monoculture of wheat, more susceptible to meteorological vagaries than the English mix of winter and spring grains, or from a poorer communications network that caused French regions with harvest failures to suffer with little outside help.[17] Recent work has brought into question whether France or any other early modern European society let its population

[15] Wrigley and Schofield, Population History, chaps. 10, 11.

[16] See Le Roy Ladurie, "Motionless History," 129–31.

[17] See Weir, "Life Under Pressure." Weir rejects the view that France had a higher "pressure system" than England. Andrew B. Appleby, "Grain Prices," argues that after the seventeenth century England suffered less severe famines than France because it did not follow the monoculture of wheat to the same extent, harvesting major quantities of other grains that were hurt less sharply by the same climatic acts of God.

rise to levels that would entail near starvation when crops were normal.[18] Nevertheless, France was more liable than England to suffer from bad harvests, and this may be our best definition of the difference between a high- and a low-pressure demographic system. Historical demography is in a period of rapid advance, and future research should clarify our understanding of the situation in early modern countries.

Less historical work has been done on the demography of Spain than on that of England or France, but the knowledge we have at present indicates that in the seventeenth century the interior of Spain, like France, labored under a high-pressure system. It suffered three major crises of mortality in 1630–32, 1647–52, and 1684, all three following immediately upon famines. The "little ice age" of the seventeenth century, known to have affected agriculture adversely in northern Europe, appears also to have reached Spain, accentuating the irregularity of harvests.[19] Outbreaks of the plague affected the Mediterranean coast, but no evidence has been uncovered that it ever became virulent in the interior, where the major killer has been identified as typhus. In central Castile high grain prices and increased mortality went hand in hand, although the population decline experienced by various regions of the interior may also have been the result of a flight of people from a countryside overburdened by royal taxes.[20] During the War of the Spanish Succession, a series of bad harvests between 1704 and 1709 led to famine prices for grain, which reached their apex in 1710. Death rates were also high during these years, especially near the Portuguese frontier where the demands of rival armies intensified the suffering of the countryside.[21] It is worth noting that the four major Spanish demographic crises of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries were experienced in France as well, evidence that we are observing a condition that was common to western continental Europe.

With the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, the close association between harvests and mortality disappeared in Spain, as it did in France. No serious famines occurred between 1711 and midcentury, and local mortality crises appear to have been caused by influenza or typhus, not associated with food supplies.[22] No simple explanation has been found for this change, but it is one feature of a general European eco-

[18] Jones, European Miracle, 14–16.

[19] Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado, 404–5.

[20] Pérez Moreda, Crisis de mortalidad, 294–326.

[21] Ibid., 329–34, 360–62.

[22] Ibid., 334–36, 362–63.

nomic growth that began about the turn of the eighteenth century. In France more effective royal authority put an end to much of the civil turmoil that marked the seventeenth century. Production of grain for export increased in England, Prussia, and other regions, and European cities that could be fed by sea trade grew in size. Inland regions were more susceptible to shortages, but central and local governments improved roads and built canals and thereby facilitated the shipment of food into areas whose normal supplies had failed. Even a high-pressure demographic system like the French became insulated from the worst effects of crop failures. Agricultural catastrophes recurred in the eighteenth century without the earlier, devastating mortality. Poor harvests in 1788 and 1789 were instrumental in inducing popular violence in the early French Revolution, but they did not produce excessive deaths.[23]

Spain was a somewhat different case. The periphery of the peninsula—the provinces of the northern coast, Catalonia, and Valencia—followed the developments of the European maritime community. The economies of these regions began to recover from the national crisis of the seventeenth century around 1680, and after 1700 they experienced a fairly steady growth.[24] The periphery imported grain by sea from France, Sicily, North Africa, and other sources of supply. Animals for slaughter crossed the Pyrenees to Catalonia and the Basque provinces, while north European maritime nations provided salt cod.[25] The prices of wheat and other basic foodstuffs followed the same curve in these areas as in the rest of maritime Europe, convincing evidence of their integration into the Atlantic economic world.[26]

Because of the rugged geography of Spain, communications remained difficult and expensive in the central meseta and Andalusia, and these regions did not experience a comparable increase in traffic or a similar economic takeoff until the second half of the eighteenth century, and then only in some areas. After 1750 grain prices in Old Castile rose more rapidly than those in Galicia and Catalonia, evidence of the isolation of the meseta from the Atlantic economy.[27] The failure of central Spain to share in the general western economic growth meant that the country now belonged to two different economic worlds. The northern and eastern periphery formed part of the Atlantic maritime community,

[23] Meuvret, "Demographic Crises."

[24] Ringrose, "Perspectives."

[25] Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 138–39, Map 4.

[26] See Ringrose, "Perspectives," 63–65; Hamilton, War and Prices, 182–83.

[27] García-Lombardero, "Aportación," 58, Cuadro 4.

while the meseta and, to a lesser extent, Andalusia preserved an older, more isolated, and locally oriented economy, which received effective outside stimuli only toward the end of the eighteenth century.[28] Not that central Spain lacked internal trade or consisted only of subsistence economies. The presence of cities, especially Madrid, with their needs for foodstuffs and fuel from their hinterlands, the dedication of some rural areas to products intended for distant consumers—olive oil, wines, wool—and the manufacture of certain—Castilian specialties—woolens, linens, knives, and others—meant that goods moved around and agricultural products reached urban markets, sent there directly by peasants or by people who received the rent, tithes, and other payments of peasants. These were, however, economic patterns that came down from the past and owed little to contemporary outside developments, although demographic growth in the interior did stimulate their expansion.

While the entire peninsula did not participate in the Atlantic economic expansion, it shared in the general western population growth. Spain was blessed with rulers who counted their subjects on a national scale earlier than those of most other European countries did. In 1712 Felipe V ordered a count of all households, which was made everywhere but the Basque provinces, and formal censuses of all individuals were taken in 1768–69, 1786–87, and 1797. A careful analysis of these documents reveals that on average over most of the century, the population of Spain was increasing at the rate of 0.46 percent per year. This is very close to the best estimate of the rate of growth for England (0.44 percent), slightly above that attributed to Italy (0.38 percent), and well above the accepted figure for France (0.27 percent).[29]

A comparison of the population figures for the different regions of the peninsula reveals that the periphery of the north and east was growing at a somewhat faster rate than the center.[30] This is the situation that one would expect if one believes that economic prosperity is a cause for demographic expansion. The detailed study of Catalonia made by Pierre Vilar supports this explanation, for its coastal areas, open to commerce with the Atlantic world, were growing much more rapidly than most parts of the interior. Part of the reason was a difference in birth rates, but migration also played a major role in the population shifts.[31] Valencia also grew rapidly in the century, at a rate that can only be explained

[28] These are the conclusions of Ringrose, "Perspectives."

[29] See Appendix A for details on eighteenth-century censuses and population.

[30] See Appendix A.

[31] Vilar, Catalogne 2 : 42–94 and 3 : Map 56.

by massive immigration. Galicia probably had the fastest demographic expansion of the peninsula, but at the same time, as the region of densest population, it sent forth a large number of emigrants, especially single men, to the rest of Spain and America.[32] The proximity of the sea, both for the export of local products and for the import of food, is a critical factor in explaining the greater rate of growth of the coastal over the interior population.

Nevertheless, the interior was also growing, some regions faster than others. In the crises of the seventeenth century, the Castilian meseta had experienced an absolute population decline, and its growth in the eighteenth century could represent a recovery toward some kind of Malthusian limit (as indeed the growth of Catalonia did at first), according to the familiar demographic pattern described above. One can well suppose that this is what occurred during the first half of the century, but the evidence suggests that by 1750 the meseta was again approaching this limit, for food prices were becoming unstable.

After the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, central Spain produced enough grain to feed itself except for years of bad harvests. This is the conclusion to be drawn from the figures collected painstakingly by Earl Hamilton, which show that the level of agricultural prices was relatively low at this time. About 1734 Spanish prices, like those in France and England, began a long-term rise that was to continue until the Restoration in 1814, slow at first but accelerating in the fourth quarter of the century. Agricultural products led other goods, with wheat going up the fastest.[33] Within these long-term trends, brief oscillations appeared as responses to the quality of the harvests. Poor harvests in 1721 and the late 1730s pushed up agricultural prices temporarily, oscillating, as one would expect, more sharply in the meseta and Andalusia than in Valencia and Catalonia.[34] These data indicate furthermore that after midcentury central Spain experienced a growing shortage of foodstuffs. A crop failure made prices soar in 1750, and a further bad harvest in 1753 pushed them even higher. By 1754 the agricultural price level in New Castile, according to Hamilton, was 68 percent above that of 1746; the rise in the level for nonagricultural goods was only 24 percent.[35] Although harvests improved in the next years, the crown had to

[32] Anes, Antiguo Régimen, 35–42, largely based on the unpublished work of Francisco Bustelo.

[33] Hamilton, War and Prices, 173, Chart 5. See also Anes, Crisis, 220.

[34] Hamilton, War and Prices, 143, 148–49, 184, Chart 7; for Catalonia, Vilar, Catalogne 2 : 338–40, 3 : Atlas et graphiques, no. 69.

[35] These are the ratios that result from Hamilton, War and Prices, 172–73, Table 2.

send grain to Andalusia in 1757–58 to meet a shortage there.[36] The royal ministers were beginning to find the threat of famine a matter of concern. The evolving relation between food production and population growth in the interior must be considered a major factor in understanding the history of Spain at this time.

The demographic expansion of Spain does not suffice to explain the increasing sensitivity of the agricultural price level. The Polish historian Witold Kula has argued that in a mixed subsistence and market economy based on peasant farming, the amount of the grain harvest that reaches the market fluctuates more sharply than the total harvest. Peasants try to keep a constant amount of grain for themselves before selling any, while landowners (which in Spain included religious institutions) take care of their needs before disposing of their surplus.[37] This would explain sharp price fluctuations, which primarily affected urban dwellers because the peasantry as a whole relied only marginally on the market for their food.

The long-term imbalance came about because of rural and urban demographic expansion that caused suffering to both sectors. As the number of peasants grew, so did their propensity to consume the food they produced, but they were not in a position to withdraw much grain or other staples from the market. Landowners, seigneurial lords, the church, and the king drew payments from the farmers for rent, feudal dues, tithes, and taxes, and peasants made most of these payments in kind. Such obligations remained in force, whatever the size and number of peasant families. The grain and other products collected in this way provided most of the foodstuffs that reached the urban markets.[38] Peasants sold their surplus in the market, and they could reduce this amount as their needs rose, but they could not suppress the trade entirely. They had to obtain some cash to pay rents due in coin and to buy the limited outside products that they needed. Part 2 of this study will uncover some of the ways in which peasants of Castile and Andalusia struggled to maintain their real income. Their plight had little effect, however, on the long-term trend of prices.

Urban dwellers would also suffer if they had to rely on domestic food supplies. Most of the large cities in Spain, as elsewhere, were near the sea and could be fed from abroad: Barcelona, Valencia, Málaga, and Cádiz. In the heart of the meseta, however, lay Madrid, the largest city

[36] Ibid., 157.

[37] Kula, Economic Theory, 66–67.

[38] See Anes, Crisis, 338–39.

in the country. No other European metropolis of its size was like it, for it relied exclusively on land transport for its supplies. Since its establishment as the capital of Spain in the sixteenth century, its demands had strained the transportation capacity of the meseta, forced provincial capitals to compete with it for supplies, and caused the royal government continual concern. Between 1685 and 1800, it expanded from about 125,000 to nearly 200,000 people, a rate of approximately 0.41 percent per year, faster than the rest of central Spain, evidence that it was the recipient of considerable inmigration. After midcentury the city imported annually more than half a million fanegas of grain and legumes, half a million arrobas of wine, one hundred thousand arrobas of olive oil, three hundred thousand of meat, fifteen thousand hogs, and proportional quantities of fuel and other rural products. In the 1780s an average of seven hundred carts and five thousand pack animals arrived every day in good weather with cargoes to supply the city.[39] The market for farm products in Castile meant primarily the demand of Madrid, which dominated the entire region and provided incentives to expand commercial agriculture. By comparison, Valladolid, with 20,000 people, and Salamanca, with 16,000, were small provincial centers, but they too drew on the agricultural market. Zaragoza, whose population rose from some 30,000 in midcentury to 45,000 in 1800, dominated the region of Aragon much as Madrid did that of Castile.[40] Andalusia was more highly urbanized. The largest cities, Seville and Granada, had populations of 85,000 and 50,000, although Seville could also receive supplies by sea up the Gaudalquivir River. The relative prosperity of the region attracted immigrants from northern Spain, strengthening its urban centers.[41] Except for Madrid, the cities of Castile and Andalusia may not have been growing at a faster rate than the country as a whole, but any growth resulted in increased demand, to which agricultural price curves responded.[42]

[39] Ringrose, Transportation, 39–40 for products except wheat. For wheat, Ringrose, Madrid and the Spanish Economy, 110, 350 (Madrid needed about 1,500 fanegas of wheat per day in 1767, or 550,000 per year). The fanega was 55.2 liters, the arroba, 11.5 kg. The relationship between the Madrid market for foodstuffs and the countryside is discussed, ibid., 174–90. On the population, ibid., 26–29, and Ringrose, "Perspectives," 75–79.

[40] Valladolid, Zaragoza: Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado, 187, 243–44; Salamanca: Real Academia de la Historia, Censo de España (1787), legajo 9-30-3, 6259.

[41] Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 87; Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado, 225–33.

[42] Ringrose deals with both the urban market for agricultural products, especially Madrid, and the rural incentives to withdraw production from the market in Madrid and the Spanish Economy, 174–90.

3

With an increasing rural population and a growing demand for food, the value of land could be expected to rise vis-à-vis labor, the other major factor of agricultural production. There is in fact evidence that rents were going up while wages remained stagnant.[43] These circumstances produced a strong incentive to change land uses from extensive to more profitable intensive types of agriculture, and land was becoming an attractive investment opportunity. In a region like Catalonia, which had water available and could sell on the international market, capital was put into new irrigation works and market-oriented plantings like nut trees, olive groves, and vineyards.[44] Similarly, Andalusia, able to import grain by sea as far as Seville and to ship out more specialized produce, exploited the comparative advantage of its climate and soil to extend olive groves and vineyards, in some places at the expense of land sown in wheat.[45] Part 2 of this book will observe this development in detail in the towns of Jaén province. Farther in the interior, the obvious response was to bring pastures and wastelands under the plow, and this study will show that such a response was indeed occurring.[46] Parts of the meseta had long produced wine and some olive oil for local consumption, and some of this production also expanded, especially in the second half of the century.[47] Throughout the peninsula, economic incentives were bringing about changes in the uses of the land.[48]

There were, however, obstacles to the transfer of land to more profitable uses, particularly in Castile. The most important were legal restrictions on the exchange of ownership or use of land. They applied to church and public properties and to lay estates that had been established as entails, while the crown had guaranteed the Mesta, the guild of sheep owners, and the Real Cabaña de Carreteros, the teamsters' guild, the continued enjoyment at fixed rents of the pastures grazed on by their animals. The public properties went back farthest in time. During the early reconquest of Castile and León from the ninth to the eleventh centuries, when the Christians were moving into the northern meseta, they

[43] On the rise in price of land: Anes, Crisis, 274–91; Defourneaux, Olavide, 131; on the stagnation in price of agricultural labor, Anes, "Informe, " 100.

[44] Vilar, Catalogne 2 : 219–21, 242–91, 321–31; Giralt, "Técnicas."

[45] Anes, Antiguo Régimen, 189–90.

[46] See also Mem. ajust. (1784), §249, 173.

[47] Anes, Antiguo Régimen, 171–77. See Huetz de Lemps, Vignobles 1 : 306, 309, and 318, on the extension of vineyards in Salamanca province.

[48] See also Anes, Antiguo Régimen, 167–69 on Aragon, 191–95 on the northern coast.

took over many territories that were empty of people or thinly occupied. The written sources that have been preserved permit only a shaky reconstruction of the process of settlement, but it would appear that as a general rule, all the land was assumed to belong to the crown or, by tacit or express cession of the crown, to the military leaders who recaptured it or in common to the settlers who came in and established new villages and towns. Private property developed through occupation and cultivation by the settlers, a process known in Castile as presura and escalio, which resembled squatting on the American frontier. As the Reconquista advanced beyond the central sierras after the eleventh century, the Christians captured regions already well populated, where most residents remained under the new rulers. Here too there was much vacant land, and it too belonged now to the crown, unless a king granted it to another person or body.

Lands that were not established as private property or ceded expressly to a town or an individual and remained as wastes and common pastures were known as tierras baldías or simply baldíos. They included the mountains, barren wastes, woods, and rough hills of scrub growth, to which the term monte applied, all of them uncultivated and many of them of no use. Those parts of the baldíos on which local livestock grazed or which provided firewood—known in Spanish as tierras de aprovechamiento común (lands of common use)—were vital to the economy of the peasant villages. By early modern times it would appear that all the surface of the peninsula, except possibly some remote mountain wildernesses, had been allocated to one town or another or to several towns jointly.[49] It was a moot point, however, whether the unused land within the limits of a town, the baldíos, belonged to the crown or the municipality. In practice it made little difference, because the kings protected the use in common of these lands, but it did mean that once the Mesta had acquired their use as pasture, it could henceforth insist on the right to their use.[50]

During the population expansion of the sixteenth century, new squatters settled in the baldíos, and Felipe II, in need of money, sold private title to these lands to the squatters or to their towns. The king also sold off other baldíos that were still unbroken. Sales of baldíos became one

[49] Such was the case of the Montes Universales of eastern Aragon, common property of twenty-three villages (Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado, 245).

[50] This discussion is based primarily on Nieto, Bienes comunales, 54–65, 101–132. Vassberg, "Sale," 631–34, also has a valuable discussion of the nature and legal position of the baldíos.

of his largest sources of royal income. Faced with strong protests of the towns and cities of Castile that the loss of these pastures was harmful to their agriculture, in 1586 the king ordered a halt to sales of baldíos that were being used by local farmers and demanded in return the approval of a new tax known as the millones .[51] A century and a half later, in 1737, when the demand for land was again rising, Felipe V, in need of funds to construct the royal palace of Madrid, reopened the sale of baldíos, only to face the strong protest of city and town governments. Fernando VI in 1747 halted the sale of lands that were being used by local residents and the restoration of those that had been sold, but he maintained the right to sell baldíos that were not being used. The legislation of Felipe II and Fernando VI implies that the king had the ultimate title to the baldíos, while recognizing the claim of the towns to lands of aprovechamiento común.[52] Nevertheless, the catastro of the Marqués de la Ensenada attributed the title of land not held by specific owners to the municipal councils, so that the question of ownership of the baldíos remained open.[53]

Except in the north and on the Mediterranean coast, most settlements were closely nucleated. Cultivated lands and improved pastures and meadows surrounded the village or town, and the baldíos lay beyond this ring. In central and northern Castile, where most towns were small and close together, baldíos might hardly exist, but in Andalusia, La Mancha, and Extremadura, where settlements were larger and frequently far apart, the wastelands were very extensive. Spurred on by the profit in land, private individuals, noble lords (señores ), and religious orders were surreptitiously taking over large tracts of the baldíos for plowing or private pasture, while city councils appropriated them to rent for municipal income, allowing the tenants to cultivate them.[54] What to do about the baldíos was a question that would concern royal advisers for the rest of the century, for in them they saw an immense resource and, whoever had rightful title, they believed the king had full authority to dispose of them.

Not all public lands belonged to the crown. The municipalities had open pastures and monte, lands of common usage that had been specifi-

[51] Nieto, Bienes comunales, 161–62; Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 91.

[52] Nieto, Bienes comunales, 135–68, esp. 164–67; Rodríguez Silva, "Venta de baldíos."

[53] None of the lists of property of the catastros of the seven towns studied in Part 2 show any royal property. Monte and pastures are assigned to the municipal council, even the vast stretches of the Sierra Morena belonging to Baños, much of which was later used to found the colonies of Sierra Morena.

[54] Rodríguez Silva, "Venta de baldíos," 8–12.

cally deeded to them, and they also had fields, meadows, and buildings that they rented to their residents or even to outsiders. These properties were known as the bienes de propios or simply as the propios, and their rent was one of the main sources for municipal budgets.

Properties that belonged to churches and cathedrals, religious orders, charitable institutions, and ecclesiastical funds were said to belong to manos muertas, mortmain in English, and were also normally barred from sale. They included the places of worship and monastic houses, the rural and urban properties that churches and religious orders had at some time purchased, and the properties that pious individuals, out of generosity or seeking to offset their sins in the eyes of the Lord, had bequeathed to ecclesiastical institutions and foundations to provide income for their activities. The building and maintenance funds of churches (fábricas ); the emoluments (capellanías ) of certain priests; the funds for the upkeep of chapels and shrines and the performance of services at them, for the recital of masses in memory of deceased persons (memorias ), and for charitable activities such as providing dowries for orphaned girls; the income of confraternities and the funds to run hospitals, orphanages, old-age asylums, and like institutions; as well as much of the regular income of parish churches, cathedrals, and religious orders came largely from property owned in mortmain. Because the purpose of these properties was to provide income, they tended to be of above-average quality and could easily become the object of desire of individuals looking for ways to profit from the rising demand for agricultural products. They will play a central role in this story.

The third kind of entail applied to the estates of individual families. By legally enforceable acts, the owners of these estates at some time in the past had established them as inalienable and indivisible units that were passed on from generation to generation by primogeniture. They were known as vínculos legos or, more commonly, mayorazgos.[ 55] Not only real estate but all forms of property could be included, such as royal bonds or juros, the ownership of local public offices, seigneurial jurisdictions, and other privileges. The usual justification for the mayorazgo was that it protected the nobility as a class necessary to the monarchy by preserving its patrimony from being squandered by prodigal heirs, although the law of 1505 that governed the creation of mayorazgos did not restrict them to members of the nobility.[56] Some mayorazgos

[55] Clavero, Mayorazgo.

[56] In the Leyes de Toro (1505), Nov. rec., X, xvii, 2.

were vast estates belonging to titled aristocrats, but others were modest holdings of provincial hidalgos and commoners.

As direct lines died out or as mayorazgos went to female heirs for want of males, two or more mayorazgos could become the property of the same family. Although they legally remained distinct entities, in effect they became a single entailed estate, for they would normally follow the same line of inheritance. This was one way in which an estate could assemble widely scattered properties, as many great artistocratic holdings did.

Vinculación operated in various ways to check the economic forces that pushed for changes in agriculture. Most obviously it prevented the sale of land by inefficient, bankrupt owners to persons with capital who could farm it better. There was no reason why the legally prescribed heir should be the best administrator among the siblings, but even if he was, he could run into difficulty in seeking to make improvements. He could not assume a mortgage for this purpose, because at his death all liens would be nullified so that his heir would receive an unencumbered estate. With royal authorization the rule on borrowing could be relaxed, and in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries a number of aristocrats had received permission to borrow against their mayorazgos, but the purpose had seldom been agricultural improvement. Paying off debts incurred in the service of the king or the maintenance of conspicuous consumption were more common purposes.[57] Legally an owner could mortgage or sell parts of his estate that were not entailed or use other unrestricted funds to improve a mayorazgo, but the interests of his family would discourage him from doing so. Improvements in the mayorazgo would be transferred with it, and his other heirs would lose part of their anticipated inheritance. Finally, by prohibiting long-term leases, vinculación also discouraged enterprising tenants from improving the properties.

Despite all of these forms of entail, much property, both in land and buildings, was owned outright by laymen and could be freely exchanged. It is tempting to contrast favorably these properties with those that were inalienable, but in practice the difference was only relative. The laws of inheritance provided strict limitations on the disposition of estates. Most was destined to the direct heirs (the portion known as la legítima de los descendientes ), with each entitled to a specified minimum share; and no more than a fifth could be given outside the family to, for ex-

[57] Jago, "Influence of Debt."

ample, a religious fund. Because of these rules, an estate was seen more as a family holding than as the individual property of the current owner, and there was reluctance to sell any part of it. Thus law and custom worked to keep off the market even land that was legally free to be exchanged.[58]

Except for an estimate of the extent of ecclesiastical property, based on the catastro of the Marqués de la Ensenada, it is impossible to state what proportion of Spanish soil fell into each of these different types of ownership. There seems no question that the Baldíos were very extensive, possibly covering more territory than all the other lands together. An eighteenth-century writer estimated that of 136 million fanegas (a measure roughly equal to an acre) in Spain, 89 million were Baldíos,[59] while Olavide, intendant of Seville under Carlos III, asserted that two-thirds of Andalusia was uncultivated and deserted.[60] Although hardly exact, these estimates are a good expression of the magnitude of the wastelands. Of the remaining land in Castile, which includes all entailed and free private holdings, ecclesiastical estates, and municipal property, both of aprovechamiento común and propios, the catastro indicates that about 15 percent of the land belonged to the church if the area is taken as the basis and 20 percent if the annual return is the basis. The provincial summaries of the catastro listed ecclesiastical property under a separate heading, making possible this calculation, but the different types of secular property were recorded only in the individual town surveys and the enormous task of assembling this information for the entire kingdom probably never will be undertaken. Although statements have been made about the extent of mayorazgos, no reliable figure can be advanced.[61]

Beyond the various forms of legal ownership, a different kind of institution prevented the free employment of the land. This was the Mesta, the guild of owners of migrant sheep, which dated from the thirteenth century. Because of the climate and geography of the country, the flocks of merino sheep, noted for the fineness of their wool, spent the summer in pastures in the central and northern sierras and were driven south before the snowfall to distant fields in Valencia, Murcia, Extremadura, La Mancha, and Andalusia, to return north in the following spring before the summer heat burned up the southern grasslands. In their semi-

[58] Cardenas, Ensayo.

[59] Nieto, Bienes comunales, 140–41.

[60] Olavide, in Mem. ajust. (1784), §921, 281.

[61] See Appendix B.

annual migrations, tens of thousands of sheep followed long-established walks, or cañadas.

For centuries merino wool had been one of Spain's leading exports. The crown, eager to encourage a trade that brought it much revenue, had granted the Mesta extensive privileges and its own courts to ensure their observance. Among these privileges, the right of posesión ensured the members of the Mesta the continued use of any pastures they had ever occupied without an increase in rent. Extensive baldíos in Extremadura, La Mancha, and Andalusia as well as communal lands and baldíos in the northern and central sierras and private pastures were used by the Mesta, while pastures near the cañadas were also subject to the periodic invasion of the flocks. The right of posesión was a disguised form of entail, which restricted the land to its present use. By midcentury, farmers had begun to invade and plow up pastures reserved to the transhumant sheep, leading to lengthy lawsuits brought by the Mesta to preserve its rights.[62] Before towns could break new ground in the baldíos used by the migrant sheep or owners of rented pastures could recover them for their own use, they had to overcome the opposition of the Mesta. As the century progressed, the royal government received many complaints and petitions over this issue.[63]

4

Spanish agriculture followed myriad practices in the eighteenth century, only a few of which have been studied. No generalized pattern can reflect them all faithfully, yet some broad strokes are needed for orientation before proceeding with the account of individual and official responses to the new demand for foodstuffs after midcentury. One may turn first to the division between center and periphery that marked economic and demographic developments.[64] Although proximity to the sea seemed to offer all the coastal areas the possibility of participating in the maritime economy, the agriculture of only certain districts was able to take advantage of it. The Mediterranean lands of Catalonia and Valen-

[62] Mem. ajust. (1784), §249, 173.

[63] The Mesta in the eighteenth century and the royal efforts to reform it are the subject of Mickun, La Mesta. The older work Klein, Mesta, is still valuable.

[64] Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, chap. 4, gives an extensive description of the landowning patterns of this period, and I shall not repeat it here. To bring the picture up to date, there is the authoritative survey of Anes, Antiguo Régimen, 163–95, and the relevant sections of the marvelous survey of the economy and administration of the different regions of Spain in Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado. Also relevant, although concerned with a later period, is Malefakis, Agrarian Reform, chap. 2.

cia flourished under the impact of domestic population growth and foreign trade.[65] Catalan farmers were especially prosperous. Few owned the land outright, but the tenants enjoyed long-term leases, censos emfiteúticos, which ran indefinitely or, in the case of vineyards, for the life of the vines. They guaranteed the lessee the use of the land, the dominio útil, leaving to the owner only the dominio directo. As a rule, farms were consolidated single-family holdings called masías, and Catalan customary law provided that the farm be inherited as a unit so that subdivision did not occur. This typical property was thus bound by a form of entail, but it did not produce pernicious economic effects because there was no restriction on the use of the land. Pierre Vilar has shown how Catalan agriculture progressed under these conditions. Landowners and tenants cooperated to extend irrigation and introduce new crops that could be sold on the international market, such as wine, nuts, and dried fruits. The profit from these products provided the capital for agricultural improvement and foreign exchange to pay for imported grain and meat. Indirectly, the savings accumulated from farming contributed to the remarkable expansion of Catalan trade and manufacture in the second half of the century.

Along the coast south of Catalonia, the terrain was divided between rough, arid uplands, about which we know little other than the fact that much was devoted to the pasturage of sheep, and the coastal plains, which included rich irrigated valleys known as huertas or vegas. These latter enjoyed a great expansion of agriculture and an accompanying growth of population. In Valencia the cultivation of rice spread rapidly in newly developed fields along the coast, providing food for a growing population, while plantations of mulberry trees supported the worms that spun the raw material for Valencia's fast-growing silk industry. Local lords received heavy seigneurial dues, up to a quarter or a third of the harvest of certain crops, but the fact that farmers were guaranteed the dominio útil encouraged them to break new ground and invest capital in their exploitations. Here too agriculture provided the basis for a flourishing economy. The huerta of Alicante and the southern coast of Granada enjoyed similar prosperity. Products included dried fruits, nuts, and select wines, such as that of Málaga, much in demand in foreign and domestic markets.[66] The agricultural products of the Mediter-

[65] Vilar, Catalogne, vol. 2, part 2, provides a brilliant study of the evolution of Catalan agriculture in the eighteenth century.

[66] On Valencia, see Anes, Antiguo Régimen, 167–69; for Alicante and Granada, Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 102.

ranean coast, along with the fine sherry shipped out of Cádiz, went to the American colonies and penetrated the markets of the advancing countries of northern Europe.

The northern Atlantic coastal fringe from Galicia in the west to the Basque provinces by the Pyrenees told a different story. Mountainous terrain and difficult communications combined with the unrestricted subdivision of properties to discourage the development of commercial agriculture. Here the most notable development was the introduction of maize in place of grains from Galicia to the Basque provinces. A study of Guipúzcoa at the eastern end of the coast indicates that the switch began there in the seventeenth century and was accompanied by marling the soil with lime, which permitted the elimination of most fallow. In addition, much pasture and wasteland was broken to provide harvests for an expanding human and animal population.[67] Basque law maintained the farms as single, hereditary units called caseríos, exploited individually to the benefit of the farmer, but local custom did not prevent them from being subdivided among tenants. A recent study of Vizcaya indicates that during the course of the century as the population grew, the number of tenant farmers rose sharply, while that of farmer owners declined slightly. By 1800 there were almost twice as many tenant farmers as owners in the region studied.[68]

In the western half of the northern fringe, the unitary family farm gave way to nucleated towns and exploitations that grouped a number of parcels. With demographic expansion, this pattern encouraged the multiplication of tiny units. Western Asturias and Galicia became plagued by the problem of minifundia, small uneconomical exploitations worked by poor tenants. In Galicia most of the land belonged to religious institutions. At some time in the past, the owners had accepted permanent leases called foros with rents that by the eighteenth century represented a very low return on the value of the land. The tenant holders of the foros took advantage of the situation to sublease their lands in smaller units to men who actually worked the soil, while they, now middlemen called señores medianeros, came to enjoy the status and leisure of hidalgos. Because the foros usually stipulated what crops were to

[67] Fernández Albaladejo, Crisis, 85–91, 181–228; Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado, 132–33, 151, 163–64.

[68] The unpublished thesis of Emiliano Fernández de Pinedo, "Crecimiento de Vascongadas," reports that in eighty-four sample towns of Vizcaya there were 829 owners and only 526 tenants about 1700, but 791 owners and 1387 tenants in 1800 (cited in García-Lombardero, Agricultura y estancamiento, 151). See also Fernández de Pinedo, "Entrada de la tierra," 100–101.

be raised, they hindered agricultural changes in response to market demands.[69]

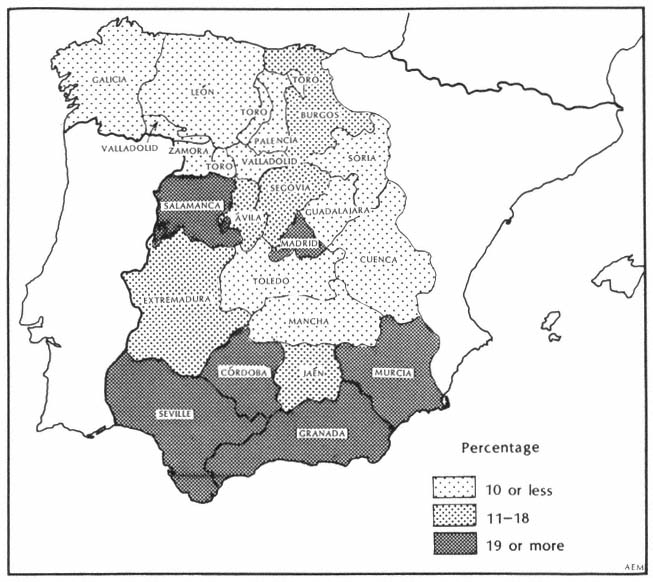

Except for concern about the plague of Galician minifundia, developments in the periphery gave the royal policymakers little cause to worry. On the contrary, they found in the family farms, long-term leases, and emphyteusis of these regions models to be recommended elsewhere. The problem lay in the interior. The predominant pattern of landholding divided the central Castilian meseta into two distinct parts, one with small farms and villages, the other dominated by large properties and large towns. The obvious division of the meseta into Old and New Castile by the rugged central mountain range offers the temptation to draw the border between these two parts along this range, but this would be a mistake. Rather, the frontier is an irregular line running from northwest to southeast, approximately from Salamanca to Albacete, passing west of Madrid (Map 1.1). Western Salamanca province lies in the territory of large farms, while the hilly region of New Castile known as the Alcarria, comprising the provinces of Guadalajara and Cuenca as well as Madrid province, is characterized by small towns and properties. One could extend the small-farm region north and east of Castile to include southern Navarre and Aragon, although less than half of Aragon was cultivated. The rest, dry and of poor soil, was given over to sheep.[70]

While it is dangerous to generalize on the basis of current knowledge, it does appear that the region of small villages and small farms was dedicated to arable and livestock, the balance between the two and the nature of the harvests or livestock depending largely on the terrain and climate. Many residents (vecinos ) of the villages and towns owned some property. According to the census of 1797, the percentage of men engaged in agriculture who were landowners in this region went from a low of 11 percent in Ávila and 13 percent in Valladolid and Guadalajara to 46 percent in Navarre and 48 percent in Aragon. Except in Palencia, less than half the men engaged in agriculture were hired laborers, a strong sign that most of the exploitations were small, family-run affairs.[71] The distribution of individual exploitations into parcels of arable scattered within the limits of a village and sometimes beyond it permit-

[69] García-Lombardero, Agricultura y estancamiento, 90–110, esp. 94–95.

[70] Compare Map 3 of Malefakis, Agrarian Reform, 31, "Area held by large (over 250 hectare) owners." Although the data for it are of the twentieth century, the general pattern would apply also to the eighteenth century. On Aragon, see Domínguez Ortiz, Sociedad y estado, 240–45.

[71] See Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 92–94, Map 1 and accompanying table.

Map 1.1.

Old Regime Spain, Provinces of Salamanca and Jaén

ted each farmer to harvest crops during all the years of the local rotation and to share in the other agricultural activities of the village. The farmers had the use of the common pastures and the fields in fallow for the support of their animals, and certain individuals could rent grain fields and meadows owned by the village councils, the propios described earlier. A number of districts in the northern part of this region were noted for their highly developed patterns of periodic redistribution among the vecinos of the communal pastures and grain fields.[72] Nevertheless, the migrant sheep of the Mesta spent the summer in many uplands of this region, and the right of the Mesta to preserve its pastures could pose an obstacle to their exploitation by the villagers.

The number of landowning farmers should not, however, be confused with the distribution of the ownership of the land. To judge from the reports of royal intendants and the results of Part 2 of the present study, few peasants owned enough land to satisfy their needs. In most cases those classified as landowners must have possessed one or a few

[72] See Costa, Colectivismo, part 2.

small parcels and had to rent the rest of their exploitation on short-term leases, three to nine years being their common duration. Those who farmed for their own account were known as labradores, but their characteristic feature was to own a plow team, not an exploitation. In most areas the bulk of the land belonged to the village councils or the local parish church and religious funds, a situation that favored the vecinos, or to nobles and other laymen and religious institutions and foundations residing or located elsewhere, such as the provincial capital or district seat (cabeza de partido ), in which case the vecinos were at a disadvantage. We shall see in Part 2 that the share belonging to these various categories of owners varied widely, depending in part on the nature of the local terrain and the distance from active urban centers. As noted earlier, the major share of the products of this region to reach the market left the villages in the form of rents, tithes, and similar obligations. Where land was owned locally, markets were usually distant; and elsewhere the conditions of farming were largely determined by short leases, which called for payment in specified quantities of certain crops. Here the peasant was not in a good position to respond to market forces; yet when his interest and that of the absentee owner coincided, there could be an effective response, as we shall see.[73]

South and west of the Salamanca-Albacete line, the average size of towns and agricultural exploitations was considerably larger. Towns here too were nucleated, surrounded by intensively cultivated land known as the ruedo and beyond it the more open, cultivated region called the campiña. The land would be divided into plots, some for grain, many for olives or vines, and there would also be irrigated huertas for vegetables or fruit trees, broken up into small, individual exploitations. Some of these units were owned by local small farmers, but many formed part of larger estates, including those of religious bodies. The percentage of men engaged in agriculture who were listed as landowners in 1797 was between 13 and 20 in the provinces of Toledo, La Mancha, and Extremadura, but 5 or less in the Guadalquivir valley: Jaén, Córdoba, Seville. Granada was 16 percent.[74]

The valley of the Guadalquivir was the archetypical region of large farms and towns. Although most of its farming was undoubtedly done on parcels in the ruedo and campiña, its characteristic exploitation was

[73] Many of the features of the region of small farms can be observed in the fine study of García Sanz, Desarrollo y crisis. The present province of Ávila, which includes part of the eighteenth-century province of Salamanca, is analyzed by Gil Crespo, "Estructura agraria."

[74] See Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, Map 1.

not the collection of parcels but the cortijo, a large, compact property devoted primarily to raising wheat. Cortijos tended to be distant from the town centers, in the campiña or beyond it, perhaps carved out of the baldíos. According to contemporary accounts, cortijos ran from a few hundred to two or three thousand fanegas.[75] Besides a house for the administrator or tenant, cortijos had buildings for the livestock, granaries, offices, and perhaps a bakery. They could be farmed by the owner or, as was frequent, leased to a tenant who had the necessary capital, draft animals, and implements. In Andalusia these large tenant farmers were called labradores, and their working capital might include a hundred or more yokes of oxen with their plows and other equipment, enough to take on more than one cortijo.[76]

Cortijos depended on a plentiful supply of cheap labor to be called on during certain brief periods of the year for planting and harvesting. One of the striking features of this region was the large number of day laborers. It ran from 54 to 76 percent of the men engaged in agriculture in New Castile but was 80 percent or more in the Guadalquivir valley. The laborers, jornaleros or braceros, lived in the large towns with their families, in a state of poverty that with luck was alleviated by the help of religious charities. The extensive baldíos, which theoretically should have provided a resource for the landless jornaleros, were in fact of little use to them. Without tools, animals, or capital, they could not have exploited more than a small plot, even if they had been given a chance. Every indication is that the men who controlled the town councils made no effort to give them a chance or even resisted such an eventuality, preferring to appropriate the municipal properties for their own use or that of other influential persons, and of course the baldíos were distant from the town nucleus and much of them was occupied by the sheep of the Mesta during the growing season.[77]

If social divisions were greater, absentee ownership was apparently less prevalent here than in the region of small farms. To judge from the examples studied in Part 2, the larger towns of the south tended to maintain local ownership because strong ecclesiastical institutions and funds existed within the towns and most of the important lay owners

[75] For the size of a fanega, see Appendix N.

[76] Mem. ajust. (1784), §659–62, 219–21; §663, 221–22; §678, 227–28.

[77] Anes, Crisis, 180, citing Campomanes (1771); Defourneaux, Olavide, 137–38; Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 109–10. Rodríguez Silva, "Venta de baldíos," tells of a tierra baldía in Andújar (Jaén) on the banks of the Guadalquivir where the poor of the town planted melons and other crops until in the mid-eighteenth century the nearby landowners took over these fields for their own use and drove out the poor.

were members of the local elite. The major exception to this generalization were towns under the jurisdiction (señorío ) of a noble in which an absentee señor had acquired extensive properties. We shall see one such case in the town of Navas in the province of Jaén.[78]

The cortijos, olive groves, and vineyards of Andalusia specialized in production for sale. Part of the market was located in nearby cities, part in Madrid, the American colonies, and northern Europe. The owners and tenants of these properties, exploiting labor that the population expansion was making relatively cheap, were in a good position to take advantage of changing market conditions. They faced the obstacles described above to borrowing money to finance improvements, but the improvements they were likely to undertake required little capital. They might involve replanting grain fields with olive groves or vineyards or breaking new land for this purpose. Olive trees and vines required a number of years before they produced fruit—around ten for olives and four for vines as a minimum—but with a sufficiently large estate the owner could make the transition in gradual stages.

The agricultural pattern of the south and west created a highly stratified society. The large towns and cities of Andalusia and La Mancha, dominated by aristocratic residences and teeming with landless workers and their families, approached an ideal type of early modern hierarchical society. In the north and east of the interior, the region of small exploitations, village society was more egalitarian. The difference was only relative, however. A landowning class also existed here, whose holdings consisted of numerous small fields, and it was less visible because it resided away from the villages in the district and provincial capitals. A word frequently on the tongue of contemporaries revealed the oligarchic nature of rural society throughout the interior of Spain: poderosos, the powerful ones. In Andalusia the poderosos were the men whose control of the land permitted them to exploit the braceros, appropriate the common lands for their own use, and tyrannize their districts. They included the señores and other major landowners, but the term was applied with even greater opprobrium to the large tenant labradores.[79] Poderosos also existed in the region of small farms. In Soria the name applied to large owners living in the provincial capital who

[78] See the study of Andalusia in Artola, Contreras, and Bernal, Latifundio. An excellent study of the agriculture of the province of Seville in the nineteenth century is Bernal and Drain, Campagnes sevillanes.

[79] For the use of the term poderoso in Andalusia, Mem. ajust. (1784), §294, 185; §332, 195; §661–62, 220–21; §667, 223.

rented fields to the peasants or offered loans to peasants with land and foreclosed when harvests were bad.[80] In Salamanca it was used to describe the large sheep owners who controlled the Mesta and through it obtained the best pastures for their immense herds.[81] One would certainly include in their number the wealthy churches and religious orders and the clergymen who enjoyed opulent benefices. The meaning of poderosos varied according to the local economy, but all parts of the interior had oligarchs that the term fitted. Their interest lay in marketing agricultural products, and it was largely through them that the impact of rising demand would be transmitted to the men who worked the soil.

The rising population and the increasing value of land provided the conditions for a clash of interests between the crown and the poderosos. Economic self-interest would encourage the powerful owners to circumvent any restrictions that hindered them from exploiting the rising agricultural prices and the increasing supply of labor. They could be expected to seek to control as much land as possible, whether their own or the public's, and use it as they wanted, renting it at high rates or producing directly for the market with hired hands. The crown, for its part, wanted to ensure a supply of food for the cities at reasonable prices while keeping imports at a minimum. Both the crown and poderosos sought to increase production, but beyond this common aim, their objectives were bound to conflict.

5