Man the Reader: Paradigm for a New Age

Rudolf Pfeiffer christened the Hellenistic world the "Age of the Book."[53] For Alexandrian philologists and scholars, the new age began under Ptolemy I, but as a broad cultural phenomenon it took time to evolve. By the second century, as we have just observed on the gravestones, books and reading occupied a place of central importance in the life of the average city dweller. Unfortunately we know very little about the actual production and distribution of books in the Hellenistic age. On the basis of papyri found in Egypt, we can say that the number of volumes in circulation was increasing in the Late Hellenistic period but was still far fewer than under the Roman Empire. The buying of books must, however, have been an important part of the whole enterprise of education, for about 100 B.C. the grammarian Artemon of Cassandreia could publish two volumes aimed at an already existing clientele, On the Collecting of Books and On the Use of Books . This marked the founding of a new genre of literature that was to become very popular under the Empire.[54]

The image of the reader was already a part of intellectual iconography in Early Hellenistic art (cf. fig. 71). But at that time reading was only one of many possibilities for expressing a particular form of intellectual activity. By Late Hellenistic times, however, reading seems to have become the very essence of the intellectual process in general. From now on it was no longer possible to imagine an intellectual other than with a book in his hand or sitting nearby. The image was evidently so appealing that it was eventually adopted for the great figures of the past, both poets and philosophers. Plato and Sophocles are both turned into avid readers, and even Homer—apparently undeterred by his blindness—is shown as a bent old man reading from his Iliad

Fig. 104

Homer seated on an altar, reading. Fragment of a Tabula

Iliaca. Augustan (?). Berlin, Staatliche Museen.

on a fragment of a Tabula Iliaca (fig. 104). Even the Cynics, who once despised reading, as also every other form of learning, are turned into readers. Diogenes himself emerges from his barrel book in hand, though first on engraved rings of the Early Roman period. In such instances, the motif does not carry a specific message about the subject but serves only as a general symbol of intellectual activity. The writers of old, it suggests, were also learned men.[55]

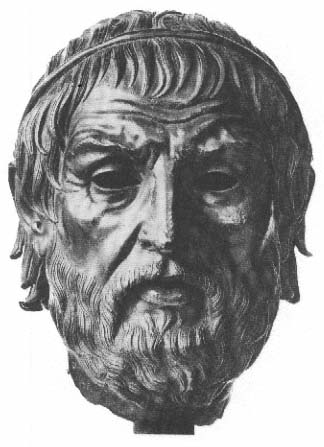

Compared to the portraits created in the later third and second centuries, these images of the poet or philosopher as reader represent a surprising standardization and impoverishment of the iconography of the intellectual. That said, we should be careful to bear in mind that we are almost entirely dependent on copies in the minor arts. Nevertheless, the coins that we noted with the type of Homer reading

Fig. 105

So-called Arundel Homer. Bronze head, probably from

the seated statue of a reading figure. First century B.C.

London, British Museum.

(fig. 88c) suggest that we cannot dismiss the reader type as an incidental or occasional phenomenon. It must have been used for major public monuments as well. One such may be represented by the impressive life-size bronze head of a poet reading, a Late Hellenistic work said to come from Istanbul and known as the Arundel Homer (fig. 105).[56]

A small marble relief provides at least some idea of the body. The poet sits in a simple chair, bent over and holding in both hands an unrolled book.

The mature, handsome face is placid and patrician. The uniform, classicizing arrangement of hair and beard concentrates our attention on the subtle movements of the lively brow and the deep-set eyes. The effect is not one of energy or mental strain; rather the artist wanted to convey the passive concentration of the reader in the portrait of a poet. The mouth is open but fully relaxed, as he reads aloud to himself. It is not enough to say that this is just an example of classicistic style and the modulation of expressionism. This is rather the new model of the intellectual. The poet is so lost in his reading that he is oblivious of the world around him. The quiet beauty of his physical features reflects a sense of inner perfection, achieved through total dedication to the classics. When viewed in this light, this work too reveals a didactic aspect.

The reader has become the exemplar of an isolated intellectual existence. Reading is a solitary process that removes the reader from the world around him. He lives instead in the world of the author and communicates only with him instead of in open discussion. In so doing, the reader creates his own private world, distant from the public life of his society. In the following chapter we shall observe how this paradigm came to fruition in Rome and its empire.