Five

Transformation by Festival Mass Festivals as Performance

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air,

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself—

Yea, all which it inherit—shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind.

Shakespeare, The Tempest

Holidays, festivals, and spectacles rapidly acquired overriding substance in Russian political culture. In 1919 crises and landmarks were manifold: the White general Iudenich's approach to the outskirts of Petrograd; the Allied blockade; the founding of the Third International. When Petrograd Pravda printed a New Year 1920 chronicle of the past year, accompanied by a full page of photographs, events that had placed the Soviet republic's fate in jeopardy were strangely muted. Instead, leading items were the November 7 anniversary celebration; Soviet Propaganda Day; the May Day burning of a dragon (of counterrevolution) in effigy. Readers might have surmised some of the year's axial moments, but the moments themselves went unmentioned. Accounts of pivotal battles were supplanted by victory speeches; legislative bodies were noted not for the laws they passed but for their convo-

cations. The only reference to the winter's dire heating crisis was the following paragraph:

Battling the fuel crisis: On November 15 the Petrograd Soviet met to discuss the question of the struggle against the fuel crisis.[1]

Ivanov's dictum was being realized: the show was becoming the event.

The "show become real," Ivanov's notion of deistvo, seemed increasingly prescient during the Revolution. Ivanov, like the socialists Sorel, Lunacharsky, and Gorky, understood myth as a contemporary, living phenomenon; and he saw it not as a remote narrative but as flesh-and-blood dramatic action. He surpassed his contemporaries in grasping the mechanics of myth. Deistvo amalgamated several elements,—drama, ritual, and myth—into a single festive performance. Ivanov anticipated modern anthropologists, such as Victor Turner, in seeing celebration as a dynamic symbolic field transforming the past it commemorates.

Mass Drama and the Professionals

Deistvo was at the heart of the debate over amateur and professional participation in festivals. Remuneration was not ultimately the issue: "amateurs" were often paid to perform, while "professional" participation was often voluntary. The issue was rather the relationship of the artist to art, and the relationship of both to the audience. The optimistic assumption underlying some early festivals was that if the working class sponsored a festival and if participants were from the working class, then the working class would identify with the festival. Deistvo theory suggested alternatives to such overly direct formulations.

In early 1920, a few professionals expressed the heretical thought that the director's skill, not class origin, was most critical to a mass spectacle. According to Tairov (who also began his career with Gaideburov), much of the rhetoric surrounding mass festivals was utter nonsense. "We are going through a period of amateurism, when everyone fancies that he can create new forms of theater." Only skilled professionals created new forms; only they could elevate mass festivals to the artwork of the future. Tairov addressed a root paradox: "Popular festivals, as such, are not theater, but when they have been created by directors and producers, they lose their popular character and become nothing more than an expanded application of the directorial art of

'mass scenes.' "[2] The gist of the paradox was that revolutionary festivals could be popular or they could be the grand artwork of the future envisioned by Wagner, but they could not be both.

Tairov was attacking a premise cherished in one way or another by Ivanov, by Lunacharsky, even by many Proletkultists. The controversy aroused by his jibes gave proof to the rule that any exchange concerning festivals, in particular the question of popular participation, pertained also to the politics of revolution. Let the reader substitute—as did many contemporaries—uprising for festival, country for theater, politician for director, working masses for audience, and Tairov had provided a critique of Leninism. Bolsheviks declared soviet power in the name of the people, and their ultimate goal was a society arising from the people; but they did not trust the people to choose their own route. The contradiction underlay the notion of samodeiatel'nost' , which inspired mystic reverence in many revolutionaries and meant something different to each of them. It inspired Lenin's understanding of the revolutionary party, which represented the working class and guided it—even against its own immediate inclinations. As might be expected, Lunacharsky, faced with the same paradox as Tairov, suggested a more Bolshevik solution: "Many think that collective creation denotes a spontaneous, independent manifestation of the masses' will. But . . . until social life attunes the masses to an instinctive observation of a higher order and rhythm, it is impossible to expect anything but merry noise and the multicolored flux of holiday clothes from the masses."[3]

Similar motives instigated the subordination of popular theater and festivals to bureaucratic control in 1919. The people's culture could not be trusted to the people. The TEO Subsection for Worker-Peasant Theater was created, and it convened at the end of 1919 to establish policy guidelines.[4] Though theater professionals were banned from the conference, administrators, professionals from other arts, and professional critics were not.[5] In fact, amateur participation was minimal, and no nonprofessional opinion was recorded in the conference minutes.

Ivanov delivered the keynote address. Although he had adopted some of the new political vocabulary, his ideas had changed little in fifteen years. His message, that revolution could beget the pan-national art of mass festivals, was received warmly by delegates.[6] Vsevolodsky-Gerngross made a similar appeal. The old stage structure had rendered spectators passive. A new drama, in which people were active participants, would bridge the abyss between actor and spectator. Russian

holiday games and rituals had once provided such a drama, and Vsevolodsky claimed that "the people must create a theater from its cultic rituals. . . . The foundation of the theater of the future will be the drama of the choral dance."[7] V. V. Tikhonovich, who presided at the congress, claimed that theater's highest purpose was to "aestheticize life"; artistic discipline would help participants transform their everyday existence.[8]

Two tendencies were evident: debaters ignored urban popular traditions, and they viewed the theater as anything but theater. Their ideal was a merging of ritual and drama that expressed and instigated national unanimity. Kerzhentsev, who came to the congress as a Proletkult delegate, gave a speech, "On Festivals of the People," in which he defined their purpose. Mass festivals were to be:

1. a means of political education, a rallying point for the slogans of the day, . . . and a means to introduce the masses to all manifestations of art

2. creative samodeiatel'nost'

3. a theater school for the laboring masses . . .

4. collective creative activity preparing the way for socialist theater, where actor and spectator are not separated, where drama (deistvo ) will be improvised by the laboring masses

5. a means to combat religion in the countryside. . . . The influence of the church has been strong to a significant degree because it offers sumptuous theatrical spectacles, often with the participation of the believers themselves

6. . . . closer to forms of drama, which give them connected dramatic unity, . . . and aim for the direct participation of those gathered in a holiday ritual.[9]

The congress mandated a national body for mass-festival organization. Oddly, Ivanov, Kerzhentsev, Vsevolodsky-Gerngross and Tikhonovich were not included on its staff. Meyerhold and Evreinov, trapped in the South by fighting, and other professional directors were also absent.

Plans for the TEO Section for Mass Presentations and Spectacles predated the congress. It was formed in October 1919 from representatives of the Association of Worker-Peasant and Red Army Theater, the subsection of the same name, and the TEO Subsection on Repertory; it was mandated to be a theoretical group concerned more with planning than with practice.[10] Members were chosen from the various arts, in line with the belief that festivals were a synthetic art form: Smyshliaev from

the theater, P. S. Kogan (a literary scholar soon to be director of the Academy of Artistic Sciences) from literature, Sofia Kogan from music, and M. V. Libakov from the plastic arts. Aleksei Gan, a former colleague of Malevich, so radical that he considered Proletkult conservative and Lunacharsky counterrevolutionary, and N. I. Lvov were also added.[11] The section did not meet until December; by that time, according to Gan, it was controlled by its radical Communist faction.[12]

In the section's "Appeal" for members, festivals were described as "an organic need lying deep in the popular consciousness," to be "created only by the masses themselves in the process of collective creation."[13] This description, of course, made the section superfluous. Despite the rhetoric, plans (never realized) were made for May Day 1920.[14] Kogan provided a balanced formula for the contributions of artist and people: the people were to supply raw energy and enthusiasm, which artists would guide into the finished forms of art. Mass festivals were, following Nietzsche's Hellenic tragedy, a product of the dialectic of Dionysian people and Apollonian artist:

We must invite on the one hand proletarian collectives . . . and on the other hand individual artists . . . whose ideology inclines toward the proletariat, who can merge [with the proletariat] in a single creative impulse.

These people of art are the masses' artistic leaders, who arouse the creative urge [samotvorchestvo ] of the masses and find the appropriate forms to express their enthusiasm.

On their part the proletarian collectives contribute to the festival their internal content—i.e., the revolutionary pathos, their intoxication, orgiasm—without which a mass theatrical drama cannot be created.[15]

Kogan's formulation, which found common ground roots in Nietzsche with the ideas of Ivanov and Lunacharsky, showed the tangled legacy of the popular-participation issue and, moreover, its kinship with the pairing of ritual and drama.

Ritual, Drama, and Myth

The desire to merge ritual and drama into a single notion, deistvo, reflected the theater world's confusion about the Revolution. Even artists and intellectuals who embraced the people's seizure of power and welcomed their participation in social governance were not always prepared for the tumult that resulted. The intelligentsia had

often imagined the people to be a homogeneous mass waiting to receive its directions. Such was the audience of the imaginary deistvo .

There are, however, essential distinctions to be made between ritual and drama that concern the relationship between the stage (and, by analogy, intellectuals) and the audience. Ritual and drama use symbols in different ways, mostly because they address different audiences. They also narrate their stories differently. Ritual, which speaks to a united community, can assume the audience comes acquainted with its conventions, while drama can create and define its own. Yet drama, because it makes its own language, can address a large and diverse community, and help it identify with unfamiliar ideas. As the Russians increasingly understood the nature of their divided audience and felt the need to reach beyond a narrow partisan group, they came to recognize the merits of drama in festival performance. It would enable them to create a new myth of revolution that could unite large segments of society.

These questions, and the solutions we are about to see the Russians try, are being probed now by modern anthropologists, foremost of which is Turner, who have described the discursive features of festival performance.[16] Correcting a functionalist inclination that narrowed celebration to a socializing agency, the anthropologists have discerned complex mechanisms of conflict resolution. Festivity's power to mediate tension is predicated on its separation from everyday social intercourse. It is defined not by the attitudes or beliefs expressed but as a discursive environment, which is symbolically isolated and must be entered across a threshold.

The festival threshold takes many forms: in time, it can be a special moment in the natural or cosmic cycle, or the anniversary of a moment in the past; in space, it can be a sacred place, a cave deep in the womb of mother earth or a consecrated house of worship. Participants in a rite must prepare themselves for crossing into the environment: they paint their faces, perform ablutions, enter the dream state of the shaman. Within the environment, their behavior is highly conventionalized; each movement, if it is to have symbolic significance, must accord with a preestablished and sanctified pattern. The language of festival performance is compact, symbolic, and mysterious. It segregates the environment from its surroundings and is meaningless outside the celebration, which enables societies to enact their fundamental myths and contradictions safely.

The language, symbols, and environment of a festival preselect and govern its audience. A highly conventionalized environment implicitly

relegates outsiders—those unfamiliar with the language—to the role of spectator. Members of the community, who are familiar with the language and perceive its significance (which they cannot always express in everyday language), are not split into spectators and performers. Society—or the members admitted to a ritual—participates as a whole and finds its wholeness in the performance.

Societies confronting periods of rapid change use myths of tradition for internal consolidation and structuring.[17] The reassuring presence of the past can help a society move into the future with confidence, while the selective presence of the past can be manipulated for political advantage. Revolutionary festivals in Russia were, as they had been in France, a way of choosing which future to pursue. Each past that was celebrated in the festivals—and there were many to choose from—suggested a different path forward.

It would be wise at this point to investigate precisely how myths are made and why some find more popular resonance than others. The assumption that the content of myths determines their fate is perhaps unwarranted. Myths are not created intuitively; like dramas, they follow formal conventions. Turner's work is valuable in that it provides tools for examining these formal aspects. It also shows a particular affinity to Russian ideas. When Turner conflates ritual with drama and claims that they are "making, not faking," he is very close to Ivanov.

Turner ascribes to festival performance the same features that tantalized Ivanov, Meyerhold, and their peers. For them, the deistvo was drama restored to its ritual origins. Deistvo drama occupied a special environment, the temple stage; performers prepared themselves with masks in order to inhabit a new personality. Dramatic language was conventionalized and deeply symbolic, and could thus address universal truths that transcended ordinary language. Drama participants (actors and spectators were not differentiated) were initiates sharing a language, setting, and beliefs. The deistvo brought them together and provided a common experience through which they merged into a united whole.

That Russians, whose society was rent by internal division, should feel the need for healing rituals is no surprise; the belief in merging (sliianie is the Russian term) was begotten by wishful thinking and historical habits. Bolshevik mass festival advocates, including feisty class partisans like Kerzhentsev and Friche, dreamed of the fraternal masses dancing and singing on city streets bathed in communal togetherness. They would in coming years occasionally fancy they had seen such a

thing. They had not. Russia was torn by internecine war. The Bolsheviks, in fact, were largely responsible for the fighting, and class struggle was a foundation of their program.

The illusion was spawned by a refusal to discriminate between drama and ritual. Ideally, festival dramas would commemorate revolutionary history, generate socialist myths and a new socialist culture, and unite the people under socialist ideology. Each potential was, in theory, latent in festivity. However, the three could not be realized together. There were, as became evident, differences between drama and ritual that had been ignored by Ivanov, were ignored by Bolshevik commentators—and are often ignored by modern anthropologists.[18] The differences were of broad consequence and should not be dismissed as marginal. Blurring the boundaries of ritual and drama obscured the contours of the historical events depicted and negated political distinctions essential to Bolshevik ideology, including some that had justified the October Revolution. Ultimately, the confusion revealed an underlying uncertainty about the nature of the Revolution and ambivalence about the creative contribution of the masses.

Drama and ritual should be viewed as poles of a single phenomenon, the symbolic activity of festivity. The differences lie in how ritual and drama create symbols and how the symbols condition audience composition and response. Symbols are more cohesive in drama than in ritual, where the kinship can be more conventionalized. The symbols of drama are created within the narrative structure and are interpreted according to its framework of meanings. Drama can yield many meanings to many interpreters, who can belong to many cultural communities. Rituals are celebrated by a community of shared discourse, usually of shared belief. Symbols can be imported into the ritual environment and do not need to harmonize with the ritual scenario or surrounding symbols. Participants are already aware of the proper interpretation and need not postulate new ones. Few people object, for instance, when the president of the United States swears on the Holy Bible to uphold the Constitution; nor did Communists object when the visage of Karl Marx was borne on a gonfalon of ecclesiastic origin or, more jarringly, when a "Red star" rose over a "tree of freedom" seen through "golden gates."

The symbols of a festival shape audience composition. Symbolic language stipulates a greater or lesser degree of foreknowledge, and the performance solicits or deters audience participation. Ritual dramas, which spoke a hieratic language, often made poor propaganda. The sponsors were preaching to the converted, for nobody else could under-

stand the symbols. A more common strategy, as is already evident, was to assign new values to the prerevolutionary lexicon of ritual. Audiences were conscious enough of ritual conventions to sense the air of solemnity summoned by the symbols; and with timely prompting they read new messages into them.

The May Day 1920 celebration in Samara illustrated both the adaptability and the incoherence of ritual symbols. The holiday was observed with a demonstration, speeches by various dignitaries, and the unveiling of monuments. The demonstration was the main event. An assembly of people of different ages, professions, and classes presented the audience with an image of social solidarity and was meant to reflect the audience itself. At the center of Samara's main square, through which the demonstration passed, was a huge globe, emblazoned with the slogan "Long Live Labor."

At its base along the sides stood two trucks: one held children with flowers, the other, boys with garlands. To the side stood various workers with the attributes of their industries: machine tools, hammers, etc., and a group of peasants with agricultural emblems: plows, harrows, seed drills, etc. Before the globe in the middle of the square . . . was the Altar of the Proletariat, an anvil and hammer garlanded by flowers. Here stood representatives of Soviet power and the municipal administration. They symbolized the mature years of the children surrounding them. A procession of thousands of people was routed past the group. The marchers were divided by category; a representative of each pronounced a greeting and presented an emblem of labor as they approached the altar. The children would then decorate the emblem with flowers, the boys with their garlands. The emblem was returned with a reciprocal greeting, and the group continued on to music. Amongst the groups were representatives of aviation, of the typesetters that had printed the slogans of the day and tossed them to the crowd along the parade route, firemen, metalworkers (with a flaming forge), and the band of Stepan Razin.[19]

If the Altar of the Proletariat was not sufficiently ambiguous, the demonstration was followed by the Coronation of the Revolution .[20]

Russians of the Civil War period were quite aware of the kinship of drama and ritual.[21] Ritual and drama both arrange symbolic events in time with dramatic plot serving a function analogous to the ceremony of ritual. Rituals, like drama, mark transitions: a change in season, a change in status, a key moment in history. Ritual consists of three distinct phases: the before-stage, the middle time of transition (the threshold, or limen); and the aftermath; drama evolved from the threshold phase. The Russians, like their anthropologist descendants, preferred to observe the similarities and ignore the differences. The key

distinction lay in the dynamic middle phase. Ritual focuses on the initial and final phases, which represent concrete stages in the life of a person, society, or nature. Transitions between phases can be abrupt and discontinuous. The middle phase is a symbolic, often brief, acknowledgment of transition. Drama, however, is born of the middle phase, the dynamic and often arduous passing between two phases of life.

This rather abstract discrimination had implications for mass drama; it determined how revolutionary events were depicted and how spectators perceived them. The phases of festive performance corresponded to three distinct historical periods; the before and after phases represented pre-revolutionary oppression and postrevolutionary salvation, while the transition phase in the middle represented the October Revolution. The outcome was that revolutionary rituals, which highlighted the before and after, never actually depicted revolution. They were static representations similar to the basic performances Kerzhentsev recommended for beginning actors: "[Show] a proletarian children's colony housed in a former lords' manor house. Show what sort of people used to live there, the savage scenes of violence that were played out. . . . Such contrasts . . . can be drawn in all fields. Before, the 'gentlemen' drank and partied; now they sell newspapers and haul lumber. Before military discipline was based on slavery; now it's built on a feeling of comradeship."[22]

For Ivanov, Lunacharsky, and many contemporaries, drama and ritual were inseparable from myth. All three were subsumed by deistvo: the representation of a crucial transformation in the life of an individual that spoke for the whole of society through its symbolic essence. The terminology was foggy, as nineteenth-century idealism could be, and it was more likely to synthesize than to analyze, yet it harbored a truth of practical significance to poets and propagandists alike. Myths are dramatic; Greek drama evolved from ritual as the enactment of a mythic past. The ultimate ambition of many festival planners was to create a myth of the October Revolution. If they were to succeed, they would have to dramatize it.

Myth shared two features of drama that were likely to appeal to a mass audience. The first was its symbolic language; mythic symbols, like the dramatic, must be cohesive. Symbols carry a continuous meaning throughout a drama or myth, and they share a common source with other symbols in the narrative. Any transformation or conversion undergone by a symbol must be explained by the narrative. Dramatic symbols can be viewed by a diverse audience, not only initiates, because they are less conventionalized and are construed by the course of the drama.

Ritual is celebrated by a community, in which participants and spectators share beliefs; drama is performed by a specialist for any spectator.

Of equal import to a mass audience was the second shared feature of myth and drama, the process of identification. This process was not the same in ritual. Myth and ritual might celebrate similar experiences; but myth assigns specific identities to person, place, and time. Ritual place and time are indeterminate—as Meyerhold noted in his Maeterlinck productions. They assume a broad applicability: rituals can be used by many people to observe birth, marriage, or death. The indeterminacy of ritual allows all eligible members of a social group to celebrate. The identity of the participant is irrelevant to the ceremony; the role and the performer are one. In myth, space is identified, and time moves by the rules of narrative progression. The leading role is assumed by a single figure, the protagonist, and cannot be transferred to another person. Action, linked by a single figure, is assembled into dramatic plot.

The paradox of dramatic identification, which runs against basic instincts operative during the Revolution, is that the collective identifies with the individual. The audience of a ritual consists mostly, often exclusively, of those who have performed or will pass through the ritual. They are initiates. Yet most rituals begin with celebrants separating themselves from the community by a symbolic act of cleansing or distancing. The transition phase is passed alone, after which the celebrant can reenter the community. In drama, the actor and audience stand apart from the role of the protagonist. Yet both identify intensely with the protagonist's experience, which generates drama's emotional impact.

There were complexities to myth that had not been foreseen. Many Bolsheviks had a grasp of its social implications, but a tendency to equate myth and ideology blinded them to its mechanics. Smyshliaev developed a plan for May Day 1920 that was a patent attempt to create a myth of revolution. Smyshliaev proposed using the myth of Prometheus, which had traveled a long road through Russian social thought. Marx was the most frequent holder of the Promethean title, while Ivanov and Scriabin had seen it as a myth of Western civilization. Vinogradov was attracted by the myth; and sovietization was consummated in the Golden King, a synthetic production about the battle of labor and capital, performed to Scriabin's Prometheus theme.[23] In Smyshliaev's socialist version, Prometheus symbolizes the "proletariat, bound to the rock of capitalism," and the Red Army effects a revolution by freeing him from his chains.

At sunrise heralds . . . spread out through the sleeping city and with a loud fanfare summon citizens to previously announced squares and streets. . . .

The square is surrounded by smoking torches, near which stand people with strange, night-black posters, black masks, holding rods of gold; these are pompous, bombastic figures, cretinous. . . . They let the citizens file by [and] assemble in the center of the square by the black figure of a deity, monstrous and oppressively large. . . . The citizens see that a man in a blue workers' shirt [Prometheus] is bound to the idol with a steel chain. . . .

Dawn arrives and the people with the rods of gold turn restless; they try to block the sun from the crowd with their black shields. But from the thick of the crowd emerges a Red Army detachment, which makes its way to the pedestal of the idol, unchains the man in the blue shirt, and topples the idol. The liberated man raises a red banner, at which time a tremendous choir, dispersed among the crowd itself, begins to sing Prometheus a hymn written specially for the occasion.[24]

The plan concludes with a call for the obligatory merging of audience and actors.

Both drama and ritual make assumptions about the audience that determine their symbolic language and its interpretation, and ultimately condition their ability to create myths. Soviet festival planners, and not Smyshliaev alone, failed to imagine their audience fully. They made an eminently Bolshevik miscalculation; they assumed that, confronted with a properly proletarian myth, the proletariat would adopt it as their own. Lunacharsky's prerevolutionary writings left little doubt as to his unabashed wish to give the masses a myth of revolution. But ideology alone does not create myths. As we have seen, myths must be structured like myths, their symbols must be mythic, and they must account for the audience and its culture. Smyshliaev, for instance, failed to note that his audience was unfamiliar with the Prometheus myth. If the Russians wished to create a myth of revolution, they would have to feature the Revolution itself, an experience shared by all Soviet Russia—and interpreted differently by its various constituents.

As Emile Durkheim suggested in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, ritual needs—and is meant to create—an atmosphere of unanimity. Spectator-participants cooperate with their community. The tendency of festival planners to assume unanimity and to fabricate myths for the whole nation was inspired ultimately by a disregard for spectator autonomy.[25] They blithely foresaw revolutionary fervor and symbolic identification. That this assumption did not correspond to the popular mood was noted by young members of Moscow Proletkult who were asked to

judge Smyshliaev's proposal. They first pointed out the obvious: it was much too expensive for wartime. More telling was the criticism that if the masses were to participate, they needed to have the same intentions as the planners: "Drawing the masses into the action is technically impossible: how can thousands of participants be inspired [to the same purpose]? How can the desire be aroused in them to take part in the drama? And, finally, how can the masses' movement be led or guided if they do not go as the initiating groups intend them to?"[26] Bely, by now an instructor at the Moscow Proletkult, had made the same objection fifteen years before in reference to Ivanov's theories.

Like the antagonists in the antimodernist campaign of 1918–19, festival planners had trouble acknowledging spontaneous mass reaction. Herein lay the paradox of samodeiatel'nost' . Participation by the untrained masses was welcome, but their creativity had to be controlled, even instigated. Several strangely contrived solutions showed the depth of the organizers' discomfort. Smyshliaev suggested putting barriers in the path of the demonstrators; the effort to overcome them would force the marchers to manifest self-activity.[27] Another suggestion, which in a few years would become general Soviet practice, was to distribute among the crowd "cells of fomenters" (iacheiki zazhigatelei ), whose premeditated enthusiasm would inspire spontaneous emotion.[28]

Play and Imagination

Overlooked has been the third element of the performative triad: play. The Hellenic Olympics consisted of rituals to honor the gods of Olympus, dramas for the tragic competition, and athletic contests to glorify national heroes. A similar interweaving of ritual, drama, and play is fundamental to festivals and performative theory.

Play takes many forms: there are competitions of skill, like sport; mimicry, the habitation of a new personality; and games of risk and vertigo.[29] The first two are most relevant here. Play exhibits features of festive behavior found in ritual and drama: a special environment, whether the playing field of games or the attitude of mimicry (the shaman's or oracle's possession); behavior distinguished from everyday conduct by conventions—the rules of the game or the "what-if" of make-believe. In game playing, these conventional, even artificial, traits free behavior from social constraints and allow creative latitude.

Mass spectacles developed from the tension of all three performance types, in which play offered a potential for spontaneous participation and creativity. The Overthrow of the Autocracy was an igrishche, a game; it was a replaying of the Revolution. Play acting stimulated a feeling of revolution that was otherwise missing. Yet Overthrow, which was performed for army units, played to a limited audience associated with the players; either they were directly acquainted, or they were, like Vinogradov's students, soldiers. The barrier between stage and audience was breached, which Russian theorists had—perhaps mistakenly—assumed was the essence of a mass deistvo; but it was breached because of previously shared experiences, the Revolution and Civil War, that lay outside the performance. If the performance was to be a unifying medium—that is, if mass spectacles were to unite a divided society—it would have to fabricate a common experience that carried symbolic moment beyond the performative environment.

Play is not essentially symbolic, although it can be symbolic because it can be interpreted. Most anthropologists would in fact take strong exception to the idea that play is nonsymbolic, and the "meaning" of play is described in great detail in John MacAloon's work on the modern Olympics. The contradiction though is not so great. Play as such is not meaningful; but it certainly can be a carrier of meaning. Placed in a proper context, like the Olympics, play can become highly symbolic. But in another context, the same game will have entirely different connotations or none at all. Significantly, the same cultural system that reads political meaning into the Olympic Games also senses that politics detract from sportsmanship—a notion that elevates game playing to noble stature. Vinogradov seems to have sensed the limits of Overthrow . The dramatic game provided a dynamic principle for depicting the Revolution, yet lacked a generalized, symbolic setting to transport the soldiers beyond immediate experience. Thus, in the next spectacle, Deistvo of the Third International, the overtly symbolic globe was placed center-stage.

Play could make several contributions to revolutionary fêtes. Dramatic games like Overthrow were capable of depicting revolution dynamically, a welcome contrast to the ostentatious rituals sweeping Soviet Russia. Of greater import was a quality that had been neglected, even by Vinogradov: make-believe. Although the materialist Bolsheviks, who were often guilty of excess sobriety, left no room for play in their cultural theories, there was a role for it in an evolving socialist culture. Makebelieve asks participants to imagine themselves in new surroundings and to create behavior appropriate to that environment. The setting and rules

of behavior can be strictly defined, as in a board game, or freely generated, as in child's play. Make-believe shares essential features with drama and ritual: conventionality and the assumption of new identities by participants. It lent revolutionary festivals a lightness that was distinctly lacking; moreover, it encouraged participants to act as they might under communism and to create new types of behavior.

The role of play in festivity, is perhaps the best explanation of why Evreinov, so unmaterialist, so unserious, and, finally, so un-Bolshevik, should have directed the most powerful and most mythic of the revolutionary festivals. In opposition to the symbolists, who returned theater to its ritual origins, Evreinov took theater along the axis of play. For Evreinov, theatricality was the essence of theater. Theatricality, theater for theater's sake, meant to him the element of play, of make-believe, a preaesthetic instinct in all life. Play was the principle of eternal creation. Children make a theater from their five fingers; dogs chase their own tails; adults ceaselessly don and doff social masks: life is a series of transformations. Play is a release from everyday exigency, a time when the imagination can transform and beautify life.[30]

Evreinov saw great therapeutic value in inhabiting new personalities. His idea was best illustrated by The Main Thing, a comedy written by him and directed by Nikolai Petrov at the Free Comedy Theater in 1921.[31] It was a simple play of changing masks. Paraclete, the protagonist, is an amalgam of goodwill, deceit, and boundless fantasy. He convinces a troupe of talentless provincial actors to deceive a group of unfortunates. The troupe's romantic lead feigns love for a fading spinster; the dancer convinces a disheartened student of her infatuation. Despite set-backs, the illusion serves its purpose; the objects of the deception are given reason to live, the actors learn the value of charity. The lives of all are transformed through art and artifice.

Evreinov believed that play was carefree; but its imaginative capabilities could have more practical uses. Play posits a conventionalized situation in which participants assume new identities and behave according to new rules. The environment imagined by play can be entirely artificial, as in sport, but it can also parallel real-life situations. Participants can perform duties they will later have to perform in a real environment; play is a form of practice in which mistakes are not followed by dire consequences.

The benefits of play were evident in attempts in 1920 to experiment with and even create socialist forms of culture in festivals. After three years of socialism, the most attractive models for socialist culture still

came mostly from utopian novels and tiny, short-lived communes. There was however a tremendous enthusiasm waiting to be harnessed, and some intriguing ideas. They were tried out by various organizations, with varying success, in mass festivals.

The army, which had already sponsored Vinogradov's studio, sponsored play as well in 1920. The military has frequently used play to prepare soldiers for war: they can learn tactics and maneuvers without the immediate dangers of the battlefield. Not only was Waterloo won, as Wellington claimed, on the playing fields of Eton; Indian warriors trained for battle by playing lacrosse, and modern armies train with war games. The military parade, like its cousin the demonstration, trains a military body to be perfectly organized. It is not just a spectacle—though a stirring spectacle it can be—it is a form of discipline without immediate utility. An army that marches well fights well; or so the theory runs. As leaders of the nascent Red Army knew, the birth of the first great Russian army had been in the spectacular war games, the instsenirovki, of young Peter the Great. In one instance a mock fortress of huge proportions, Pressburg, was built on the river Yauza; Peter's soldier-playmates bombarded it with cardboard bombs and stormed the walls with play guns in their hands. The weapons might have been fake, but the wounds received in battle were often real. Furthermore, from these games Peter acquired a very real knowledge of military technology, and from his boysoldiers emerged a generation of competent commanders and disciplined soldiers.

Red Army leaders went further; they conducted exercises as dramatic performances. On August 26, 1919, the reserve army delivered two thousand young recruits to Piotrovsky for theatricalized maneuvers.[32] The aim of the production was to give the recruits, who were preparing to enter the war with the Poles, "an emotional conception in images of the fundamental stages of the revolutionary movement and the goals of the Civil War."[33]

The Krasnoe selo camp where the tsar and his retinue had often retreated for military maneuvers during the First World War housed a natural amphitheater: a slope opening onto a large patch of flat ground. On a small stage set in the middle of that patch, actors enacted the basic plot. The maneuvers were based on the scenario of a mass spectacle performed July 19 for delegates of the Third International. It included the struggles of the First International, scenes from the First World War, and the struggle of the Red Army against its internal and external enemies. The enactment culminated in the triumph of the socialist republic.

At its most ambitious, play could propose models for life under socialism. Here, Soviet festival organizers struggled with an unfortunate property, of play; it is impermanent. Gan's plan for May Day 1920 was to create within Moscow a temporary socialist city: an environment, like a festival, in which the socialist culture of the future could be fashioned. Gan had grand ambitions for his festival city; it was to be a real thing, a form of activity that could transform the course of life. Gan was of the deistvo school that wanted to provoke permanent change. As he remonstrated, "Play has no place in the theater."[34] His stern-faced, "materialist" vision of revolutionary drama did not allow for makebelieve; yet he too expected its magic to conjure the future: "Our everyday is a day of great struggle, and at this time there is nothing more important than intense revolutionary labor directed toward communism. . . . [We must] infuse performative [deistvennyi ] content for the unfolding of new social relations, a new discipline for social labor, a new world-historical structure for the entire national and then the international economy."[35]

Constructivism, which Gan claimed first developed in 1920 among the ideologues of mass drama,[36] was art designed to have a specified effect on the social and cultural consciousness of its consumers.[37] It was a belief that proper environment makes for proper culture; constructivists engaged in devising things for socialism. In its emphasis on total environment, constructivism was related to mass festivals, but constructivism intended to create permanent environments. Festivals prefer the temporary to the permanent, the illusory to the real, a choice that Gan would not make.[38] He insisted that no props be used in his city; everything must be a real thi ng. Communal rest and eating were theatricalized; a socialist society, both make-believe and real, was created.

All the squares where action occurs are to be named for the arts and sciences. . . . Geography Square [on Agitation St.] [is to have] an enormous globe, the land sections of which will be colored red for the smoldering world revolution. . . .

Outside the city (perhaps Khodynka Field) a Field of the International will be set up with a wireless station and an aerodrome. On this field the main drama of the festival unfolds.

In the early morning prologue . . . a powerful siren calls from the Sparrow Hills and is answered by the whistles of all of Moscow's factories.

On that signal cavalry detachments, motorcycles, and cars ride from the seventeen city gates to local squares, summoning citizens into the streets along the way. On neighborhood squares, groups [of agitators] await them . . . to

involve them in the active deistvo of the holiday. Here the drama of the First International unfolds.

When this is over the masses move to the city center, . . . where the Second International is celebrated.

Finally citizens move on to the Field of the International where the fall of the Second International and the rise of the Third unfolds, as well as the transition to a socialist society.[39]

Play, in the end, requires a light touch, like Evreinov's; it tends to be irresponsible. It does not obligate its participants and makes no claim to permanence. Ironically, for all his rhetorical practicality, Gan did not take into account Moscow's dilapidated public transport. Any Muscovite wishing to watch the drama, much less participate, would have walked across the city twice that day.

In the end, Gan never had the chance to confront these problems. As had been the fate of earlier Narkompros projects, plans formulated by the Section for Mass Presentations and Spectacles were never realized. May Day 1920 was instead given over to a nationwide subbotnik, a day of voluntary community labor. In this festival, work—the foundation of socialism—was transformed into play by the special rules of holiday.

Labor Transformed

Revolution introduced socialism to the state before it did to the workplace. Socialist labor was a term as vague as it was common. To radicals, it meant worker control of factories, which the Bolsheviks tried briefly and disastrously. To Bogdanov, it meant voluntary work of the utmost efficiency and variety. To Gastev, it meant rhythmic labor movements that seemed poetic to him—and robotic to others.

The Civil War did not leave much room for experiment. Capital assets were destroyed, and resources that might have gone to repair the destruction were reallocated. Industrial labor was absorbed into the new Red Army; displacements in the work force and the aging of the industrial plant led to a sharp drop in productivity. The emergency led to a command economy in which labor conditions were not so different from those of capitalism: workers were compelled to work long hours for low pay. There was no real opportunity to try out new principles. Mass festivals offered a chance, albeit temporary and nonbinding, to establish

an ideal setting and let participants act as if the socialist economy were a reality.

Revolution can blur the distinction between holiday and everyday, but even before the October Revolution there was a strong tradition that labor would become one with leisure: it was one of many differentiations to wither away. In News from Nowhere, Morris depicted labor as its own reward and relaxation; Gastev thought of socialist work as a festival, an experience of beauty, joy, and unity. Lunacharsky went even further: he saw festivals as an organized environment in which normally "unorganized masses . . . merge into the organized."[40] This was the converse of Morris's inversion. The hope was that festivals would serve as "shock-moments [udar-momenty ] that will compel a more serious attitude [toward labor], greater discipline, and that gradually these 'abnormal' methods will become normal, everyday."[41]

Industrialization introduced a new concept of time to culture: standardized and regulated, without the irregular bursts of the natural, agricultural clock. Industrialization was impossible without standardized time; but in 1920 standard time was not enough. A superhuman effort was needed, what Lenin called "revolutionary-style" work (rabota po-revoliutsionnomu ). Work was subject to compressed, intensified holiday time. If work conditions could not be changed, the space/time environment around it could.

Work was introduced to festive culture by measures such as honoring outstanding laborers with the title of "shock worker" (udarnik truda ) and by the introduction of subbotniki and voskresniki (Saturday and Sunday workdays). "Shock work," a concept forgotten during NEP and revived by the Cultural Revolution, was in fact proposed for May Day 1920 by Kogan, chairman of the national Bureau of Mass Festivals.[42] He suggested that productivity could be spurred if labor was performed in bursts. There were corresponding proposals to bring labor into ceremonial culture: on May Day, outstanding workers were honored throughout the country. The ritual recognition of labor quickly spread; workers were thrilled that "their everyday life had become an object of ceremonial recognition."[43] The movement culminated at the December 1920 Congress of Soviets, which created a medal for outstanding labor: the Order of the Red Banner of Labor.

The most radical manipulation of labor time attempted in Soviet Russia was the subbotnik. Subbotniki were begun on the initiative of railroad workers of the Moscow-Kazan line on May 10, 1919, and a week later the initiative was taken up by Communists and "sympathiz-

ers" of the Aleksandrovsky railroad. Because transport was damaged horribly by the war, the workers contributed five hours of free labor toward restoring rail lines. This was not just overtime; it was a "special" time for special effort, and productivity for those five hours was two to three times the norm. One of the first legislative actions of the Soviet government in 1918 had been to establish the eight-hour workday; and subbotniki could be seen as a reasonable attempt to correct that wellintentioned but impractical act. In the months following the first subbotnik, Communists and sympathizers sporadically arranged their own, each chronicled with great praise on the pages of Pravda and Izvestiia .[44]

The first subbotniki seem to have been both local and voluntary; and the participants viewed them as economic contributions. But the attention of central party organs was quickly attracted; and subbotniki acquired symbolic value to complement the economic. A signal moment was the publication of Lenin's article "A Great Beginning."[45] Lenin paid little attention to the economic aspects of subbotniki; for him they represented "a cell of the new, socialist society," where workers accept voluntary discipline and labor for their own benefit. Festivals act as temporary environments in which new social structures can be created; and Lenin charged the subbotniki with "the creation of new economic relations, of a new society." Subbotniki were not additional time spent on everyday labor; they were moments of "exemplary communist work" that created a model for every day.

As party attention focused on the subbotniki in early 1920, the voluntary nature of participation became more dubious. Nonparty workers were encouraged to enlist;[46] and, judging from announcements published regularly in the central papers, many railroad workers of the Moscow region were so consistently working subbotnik hours that the pre-1918 workweek was restored. The Moscow Party Committee even formed a Department of Subbotniki; in September of 1920, the department claimed that attendance at subbotniki was good, but it also noted that Communists were taking part with great reluctance.[47]

The rhetoric generated by subbotniki became thicker as the snow of winter 1920 grew deeper on the streets. A front-page article in Pravda proposed transplanting subbotniki to the Soviet village;[48] but the very concept of subbotnik was unthinkable without urban industrial time. Saturday work was even proposed as an educational tool for children.[49] Holiday subbotniki were becoming the norm, a reversal of the socialist promise that "labor will become a holiday." The pages of the Moscow

press would announce a series of subbotniki every day; and in Odessa, for example, March through June witnessed thirteen straight subbotniki .[50] When the Central Executive Committee of the Russian Republic decreed May Day a subbotnik, it came as no surprise.

There were merits to introducing work into holiday culture as a production incentive, but there was also a disadvantage. In March through early May 1920, Soviet Russia was swamped with holidays. There were Lent and Easter; and the Soviet anniversaries of the Overthrow of the Autocracy, Paris Commune Day, International Women's Day, and May Day. The latter three were observed with subbotniki, and in March and April, special week-long (!) subbotniki were held for the newly christened Cleanliness Week, Transport Week, Labor Week, and Labor-Front Week. There was even a subbotnik to celebrate the anniversary of the first subbotnik . This work, incidentally, supplemented the compulsory, unremunerated work done by most citizens in shoveling snow off the streets. Even if workers were given no better hours than they had before the Revolution, the mental division of those hours was different. Eight hours a day was obligatory, everyday work, which no name could transform; but the rest of those hours were free, holiday labor to be performed voluntarily. As tenuous as this claim might seem, and however exaggerated the rhetoric in the central press was, productivity was much higher on those days, and work was performed more willingly during subbotnik hours.[51]

The leaders of Petrograd went to tremendous lengths to ensure that the May Day subbotnik was conducted in a holiday environment. Its mood, which contrasted with the grimness of the previous two years of war, resembled more the atmosphere and intent of Parisians' splendid Champs-de-Mars cleanup for the 1790 Fête of Federation.[52] Petrograd's Summer Garden, situated between the two work sites (Field of Mars, Palace Square) offered an ideal festival site; it was first plotted in the mid-eighteenth century, when festive culture was at its apogee. Distributed around the gardens in 1920 were classical orchestras, puppet theaters, folk musicians; a phonograph played revolutionary speeches; mandolin music filled the central canals from passing gondolas; and Euripides's Hippolytus was performed on the steep staircase of the Engineers' Castle.[53]

Previous subbotniki had been dictated by economic need and were focused on the transport crisis. Some critics, particularly the Mensheviks, felt that by grafting the May Day and subbotnik traditions together, the Bolsheviks "made a holiday into everyday." But the Bolshevik leader-

ship countered by placing the subbotniki within the "intensified, compressed time of holiday: before the Revolution May Day had been a time of intensified effort [struggle] and now too May Day was a period of intensified effort [productivity]."[54]

This was more than a rhetorical flourish. The labor assigned on May Day was overwhelmingly symbolic.[55] Palace Square and the Field of Mars were the last places in Petrograd that needed repairs. The subbotnik was designed not to rehabilitate the city's economy but to renovate its primary ceremonial spaces. Being a national festival, it could not enlist just a segment of the population, only the whole: a great effort was made to get the entire city out, and huge attendance was claimed.[56] News coverage was thorough, and the central press ensured that ordinary folk knew even Lenin had done his share, by clearing the Kremlin courtyard of loose timber.[57]

The symbolism of this May Day, whether or not it was acceptable to the populace, went deep; like the Easter that would soon follow, it symbolized a "new beginning," a resetting of time for a fresh start.[58] Much of the day's work went into symbolic groundbreakings for office buildings, factories, even new cities; in Orel, two-story apartment buildings were reportedly built in the course of a holiday spectacle.[59] The dirt of the past was to be washed away, forgotten: as an official slogan proclaimed, "The garbage you are picking up was left by capital[ism]." With the dirt, the unnatural, doglike attitude toward work that the tsarist regime had inculcated in Russians would also be swept away.[60] Khlebnikov, of all people, gave the clearest idea of what the holiday should be in his poem "Labor Holiday":

Scarlet afloat, scarlet

Held up by the lances of the crowd.

That's labor passing by, scampering

A flick of the heel in stride.

Workweek! Workweek!

The skin of shirt fronts glistens.

And a song flows on

Of yesterday's slaves,

Of workers, not slaves.[61]

Work in Petrograd was directed at cleaning the vestiges of tsardom from the symbolic centers of Palace Square and the Field of Mars, cornerstones of the baroque city. The subbotnik, which the newspapers dubbed "the destruction of the old world,"[62] was designed to break down the symbolic separation of the palace from the city whose center

it occupied: a graphic illustration of festivals' ability to cross impermeable thresholds. That morning, as a cannon roared and a military band played, tens of thousands of citizens charged the fence enclosing the square and began to tear it down.[63] The Field of Mars had hosted displays of military might under the tsars; but after years of war and revolution, it had been pounded into a huge dust bowl. The architect I. A. Fomin was commissioned to convert the square into a park;[64] a miraculous transformation from desert to garden, as in ancient tales, was to occur in the course of the holiday.

There was little spontaneity to the subbotnik and little of the play that might have sparked a creative attitude to work. Organizers viewed the work more as a ritual. Gan saw the subbotnik as the forerunner of his ideal deistvo .[65] It was "real" work; but it was also symbolic work, a work performance breeding new social attitudes. Movement, inspired by orchestral music, was theatricalized and ritualized: marching to the square and planting in time with the music.[66] Piotrovsky called the holiday the "birthday of labor," in which art and work became one;[67] and the May Day headline of Pravda proclaimed it the "great new ritual of the Red holiday."

Subbotnik labor was absorbed into holiday culture. A holiday is a discrete unit of time set off from the everyday, yet revolutionary festivals frequently featured attempts to fuse holiday and everyday, to have cake and eat it too. Introduced into holiday culture, labor was subject to holiday time: bursts of intense effort, followed by times of slack when that effort is forgotten. Such was the fate of the work of May Day. The fence was successfully removed from Palace Square, but not enough time remained to clean up the debris. The twisted fence and massive stones supporting it were left on the Palace Embankment, where they could be seen for years. The fate of the Field of Mars was even sadder; the holiday had not allowed time for careful planting of the trees, and afterward nobody came to tend them. All sixty thousand trees and bushes had died by mid-summer.[68]

History as Mystery

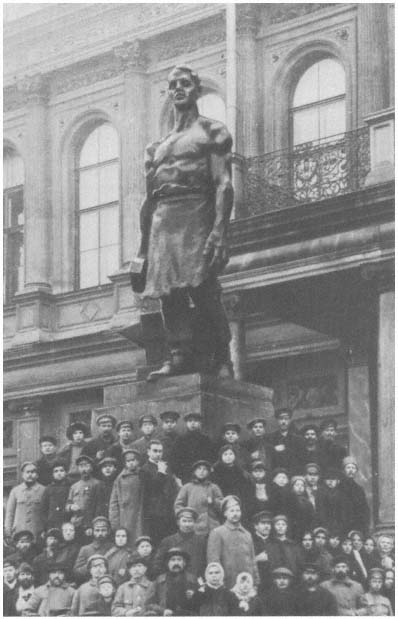

By the spring of 1920, the Bolsheviks were more confident of their power than ever. May Day, as is already evident, was celebrated with great pomp and pageantry. One of the central activities

in Moscow was the unveiling of a monument to Liberated Labor (on a pedestal formerly occupied by a statue of Alexander III). The exultation of participants was captured, perhaps even embellished, by the Proletkult poet Mikhail Gerasimov:

By the temple of Christ, on the bloody granite,

When the cannons' salute had fallen silent,

And the sun had halted at its zenith,

Lenin unveiled the monument to Liberated Labor.[69]

In Petrograd the theme of liberated labor was observed even more grandly with the first of the great mass spectacles, The Mystery of Liberated Labor . This spectacle was performed by some two thousand people, mostly army conscripts, organized by PUR in the person of Tiomkin. Tiomkin, who some forty years later would be the proud holder of four Oscars for film scores (including the score for Old Man and the Sea ), was in 1920 a young pianist just graduated from the Petrograd Conservatory.[70] He solicited the services of some of Petrograd's finest directors: Annenkov, Kugel (owner and director of the Crooked Mirror cabaret), and S. D. Maslovskaia (director of a school for opera extras); Annenkov, Dobuzhinsky, and Vladimir Shchuko—a famous architect working as a designer for the Bolshoi Dramatic Theater (BDT)—were put in charge of the set. The scenario, in keeping with the nature of "collective creation," was written by a "collective author," which included Annenkov, Shchuko, Dobuzhinsky, A. A. Radakov (BDT), Hugo Varlikh (conductor, until 1917 director of the court orchestra), Kugel, Granovsky (a Max Reinhardt student), L. N. Urvantsov (playwright), Lopukhov, and N. I. Misheev.[71] This was a mostly non-Bolshevik but very competent crew.

The former stock exchange was chosen as the site of the performance. It was a highly theatrical building; the classical portico, framed into a natural stage by white columns, made the tip of Vasilievsky Island, at the confluence of the Great and Little Neva rivers, its gallery. The square before the exchange would soon be renamed Peoples' Festival Square. The building and the square could be used two different ways: as real space or as conventional, theatrical space. The square was a part of revolutionary Petrograd; but the stock exchange, with its capitalist function and imperial architecture, was not, and the directors chose to create a purely conventional space. Canvas backdrops were painted, effectively turning a three-dimensional real space into two-dimensional conventional space; and the area surrounding the building was cordoned off.

The play did not transform the space; rather, the architecture of the exchange became a guiding metaphor for the depiction of revolutionary events.[72] The stock exchange was something of an anomaly; a neoclassical building used in the northern capital of an autocracy for capitalist commerce. It was never fully integrated into the city or its culture: not really part of Vasilievsky Island nor of the imperial center nor of the Petrograd River bank, which flanked it, the exchange was one of the few parts of Petersburg that never made its way into national literature or mythology. It was perhaps the most artificial point in that unnatural city; and it did not have the strong associations that an established space, such as Palace Square or the Field of Mars, had. That it should be used as a conventional rather than a real space is no surprise. The columned, open porch, with its sweeping staircase and the cobbled "pit" at its base, created a natural stage for mystery plays. The threeleveled space, as described in the scenario, was populated at its lowest rung by the "oppressed peoples" of history; the porch was the "paradise" of the powerful; and the staircase was the field of their battle.

ACT I

Scene i. Workers' Labor. Scene ii. Dominion of the Oppressors . Scene iii. The Slaves Are Restless .

From behind a blank wall come strains of enchanting music and a nimbus of bright, festive light. The wall hides the wondrous world of the new life. There liberty, brotherhood, and equality reign. But the approach to the magical castle of freedom is guarded by threatening cannons.

Slaves on the steps are weighed down by incessant hard labor. Moans, curses, sad songs, the scrape of chains, screams, and the laughter of overseers is heard. Occasionally the burdened grief of the prisoners' song quiets down, and the slaves stop their work to catch strains of captivating music. But the overseers return them to reality.

A procession of oppressive rulers comes into view surrounded by a brilliant suite of their underlings. The rulers climb the steps to the banquet hall. Here oppressors of all times, all peoples, and all forms of exploitation have gathered. The central figure[s] . . . [are] an eastern monarch in sumptuous dress, covered in gold and jewels, a Chinese mandarin, an obese king of the stock market, . . . and a typical Russian merchant. . . . The finest fruits of the earth grace their table. Music plays. Male and female dancers amuse the rulers, who have no interest in the wonderful, free life hidden by the gates of the magical castle. They have given themselves over completely to the drunken orgy, drowning the moans of the slaves with their shouts.

But the enchanting music has its own power. Its bewitchment makes the slaves feel the first glimmerings of the natural urge for freedom, and

their moans gradually become mutters. The banquet is seized by alarm. The music of the bacchanalia and the music of the kingdom of freedom clash. Finally there is a deafening thunderclap. The revelers jump up from their seats, terrified by their impending demise. The ecstatic slaves stretch their praying hands toward the golden gates.

Act II

Scene i. The Battle of Slaves and Oppressors . Scene ii. The Slaves Defeat the Oppressors .

The carefree, happy mood of the banquet is spoiled. . . . The slaves are abandoning their labor; . . . the isolated flames of rebellion are flaring and gradually merging into a great red bonfire. The slaves try to storm the banquet table, but their first attack is easily repelled.

Spectators are shown individual scenes from the long history of the proletariat's struggle. Roman slaves led by Spartacus race under a canopy of red banners; they are spelled by mobs of peasants led by Stepan Razin, raising the red flag of rebellion. Threatening and grand sound the strains of the Marseillaise and the carmagnole. The forest of red banners grows thicker and thicker. The sovereigns are seized by terror; their underlings flee in panic. Drums beat victory. A huge red banner, held aloft by the crowd of rebellious slaves, approaches the sovereigns. The potentates flee, dropping their crowns. Yet this is still not the final triumph of the slaves: again the bronze throats of cannon roar, and again a spirit of despondency seizes the workers. But the star of the Red Army rises in the eastern sky. With rapt attention the crowd follows its ascent. The din of drums and Red Army songs combine into triumphal music. The ranks of the Red Army grow, and the crowd is exultant. Revolutionary music reaches a crescendo. One more effort, . . . and the gates of the magical castle crash down.

Act III

The Kingdom of Peace, Freedom, and Joyful Labor

The final act is an apotheosis of the free, joyful life that begins for the new humanity. A choral dance of all nations forms around the symbolic "tree of freedom." The powerful stanzas of the Internationale are heard. The Red Army lays down its weapons for the tools of peaceful labor. The spectacle ends with a fireworks display that pours joyful, festive light on the scene as the new life begins.[73]

The traditionalism of holidays was evident in the socialist paradise. It was introduced by the leitmotif of Wagner's Lohengrin and symbolized by the tree of freedom, borrowed from the French Revolution and going back to the pagan "tree of life." The socialist city was itself described as a festival: a special, magic place.[74]

The greatest innovation of May Day 1920 was to combine drama,

ritual, and play into a single, mass festival. Even the French fêtes, which had incorporated contemporary spectacle culture, never featured dramatic art. The fêtes had been oddly ahistorical, preferring allegoric tableaux to the high arts of tragedy and comedy, or the low art of boulevard theater.

Dramatic presentation gave the Bolshevik festivals a new dimension: history. The narrative rules of drama were translated into the laws of history. The mystery play provided the directorial collective with a historical model, as it had Mayakovsky and Meyerhold. The "before" stage was the time before revolution; after came the state of grace; on the threshold humanity struggled for salvation with the dark forces of capitalism. The scenario of Mystery was, in fact, one of the earliest Bolshevik creation myths.

Mythic time, like festival time, is remote, a remote past isolated in the festival's remote present. Creation myths rely on both festive time frames: continuity to link the past to the present; discontinuity to subdivide it into history. The monumental or linking principle in Mystery was provided by a vast chorus with an identity that shifted but always represented the people. The chorus were unnamed slaves in the first act, then the rebels of Spartacus, and finally revolutionary Russians; their history was subdivided into progressive moments of revolt. In the crucible of the May Day presentation, Bolshevism became, contrary to its own dogma, the last in a series of spontaneous, leaderless revolts against the oppression of capitalist autocracy. The "oppressors" included Napoleon, the pope, a sultan, and a merchant; "struggle" included the rebellions of Spartacus, Razin, the Jacobins, and the Red Army.

The shift from ritual toward drama forced the directors to contemplate the new roles to be assumed by the audience. A ritual is a real thing, meant to mark and instigate changes in the outside world. Rituals make certain assumptions about spectators. They share a cultural and social background with participants and other viewers; they are acquainted with the symbolic language; perhaps they might, at sometime in their lives, become participants. Ritual, in other words, assumes an audience predisposed to understand and even accept its content. Drama, which creates and defines its symbols in the course of performance, can reach a diverse audience, including outsiders. Spectators are linked temporarily by their common viewing of the performance, but they are invited to interpret it according to their own experience. There was a trade-off: drama had a terrific power to depict history and address a broad audience, but it sacrificed ritual's hold on the community of participants.

The sponsors and directors of The Mystery of Liberated Labor seemed to court the benefits of both, the potentials of mythmaker and propagandizer. Their ambivalence was confirmed by the impulse to make Mystery a "real thing" and by indecision over whether to bring spectators into the performance. Ivanov's claim of reality for a deistvo was taken literally: there was real noise from real explosions; real battleships lit the stage with their floodlights; and real troops executed real maneuvers on the square. But clearly the producers, all theater professionals, had no intention of allowing the spectators, all thirty-five thousand of them, to participate; nor were the thousands of actors encouraged to improvise. Spontaneity would have been a license for pandemonium.

A trend away from free participation toward directorial control, discernible in Third International and pronounced in From the Power of Darkness, became emphatic in Mystery . Newspapers announced that "preventive measures will be taken against the accidents normally associated with large crowds"; the militia formed a cordon between stage and audience, while government officials and foreigners in attendance were segregated from the masses.[75] There was nevertheless a desire to see the performance as the long-sought deistvo; and Kerzhentsev claimed to have seen a merging of stage and audience.

The entire spectacle concluded with brilliant fireworks display, which cascaded joyful holiday light on the birth of a new life. . . . During the finale of the spectacle, an enormous chorus of workers from the entire world sang the Internationale against the background of a rising red sun. The electrified masses broke through the cable barrier separating the spectators from the place of action, surged toward the portal of the stock exchange, and joined the common singing. A grandiose choir was formed, with the spectators mingling with the actors.[76]

Kerzhentsev was in Moscow on May Day, so he could be excused for this misrepresentation. Others who saw the merging that never happened, and provided the reports Kerzhentsev relied on, had fallen prey to the old refusal to see the people—which the audience was assumed to represent—as it was, a variegated and idiosyncratic viewer. Spectators themselves seemed to sense the ambivalence of the performance; they burst through the cordon to join the final chorus but stopped dead when they reached the steps of the exchange, the beginning of "theatrical space."[77]

The legendary deistvo had a profound synthesizing capacity: it merged different arts, different ideas, different symbols, and different classes and races. Yet the expressive power of Mystery, as of all subse-

quent mass dramas, was in the ability to differentiate. The ability to differentiate was as essential as the ability to unite; both would be part of a myth of revolution.

The need to differentiate and divide elements of a spectacle was increasingly evident when complex historical topics were raised. These changes in content entailed changes in form. Professional directors began tackling the enormous technical difficulties of mass theater. The use of a detailed scenario was a major innovation; it allowed directors to break the performance into separate episodes and thus divide revolutionary history into individual events. Yet the production of this first full-scale mass spectacle revealed more problems than it solved. Comparing early scenarios with the final draft, one can see how much expressive material was lost in the vast expanse of the square.[78] The potentates of the first scenario were characterized by facial expression: one face "reflected haughtiness and a consciousness of its own divinity"; another was "marked by the stamp of debauchery and depravity." This at a distance of 100 yards. A more serious impediment involved the various rebellions and revolutions, which had to be differentiated if historical change was to be portrayed. Early rebellions were the work of a leader: "not everyone in the oppressed crowd of slaves . . . raises his voice; no, only the leaders do." Each revolt was also supposed to appear more organized than the last—as Leninist historicism would have anticipated. Thus, the first occurred when a "disorganized crowd stormed the staircase," while in the final the Red Army "headed for the [golden] gates in an orderly march." These differences were not visible in the performance. Each revolt was a swirling mass of bodies—no leader could stand out in their midst; and each revolt was equally unorganized as it stormed the staircase.[79] The acting mass was not subdivided; movement was choreographed for groups of a few hundred, which made all but the most elementary maneuvers, such as storming the staircase, impossible.

The inability to break elements of the spectacle into small units made the show ungainly and inexpressive, and led to contradictions between the intended message and the actual message. Without recourse to the fundamental expressive means of a mass spectacle, the directors were forced to rely on the spoken word, which was drowned in the outdoor vastness. Space was divided vertically (the lower classes below; the rulers above) but not horizontally (left and right halves of the stage mirrored one another). The episodes of the scenario were selected and assembled on a principle of similarity, with intervening time being elimi-

nated; along with the use of the chorus, this meant that episodes, the basic components of the production, all resembled each other. History seemed to be cyclical.

The Influence of Popular Theater

The leaders of Petrograd were so impressed by the performance that they decreed that "the stock exchange will be used this winter for the production of mystery-type spectacles."[80] An entire series was planned, including: War against White Poland, on the steps of the Engineers' Castle; The Taking of the Bastille, in the Summer Garden; The July Days, at the Narva Gate; and the Holiday of the Defense of Petrograd, in front of St. Isaac's Cathedral.[81]

Calmer heads and more critical minds counseled modesty. One person objected entirely to the appropriation of the noble title of mystery for the production: "I remember The Taking of Azov, a cannonade in three acts with artillery pieces, the navy, and the destruction of fortresses. . . . The producers of that show called it an extravaganza [feeriia ]. That, at least, was honest."[82]

But, pretense aside, Mystery had been entertaining. Shklovsky, for instance, was impressed by the ability to incorporate "real" things—for example, a military parade.[83] His was a common-sense approach that said the spectacle was wonderful—it just was not art. He proposed another performance in which two sections of Petrograd, the Vyborg and the Petrograd sides, be pitted against each other in mock battle.

Not everyone had Shklovsky's sense of humor. On May 3 Radlov and Soloviev directed an amateur production, The Fire of Prometheus, and some rather grandiose claims were made. The play was performed by Red Army dramatic circles, which led some to proclaim the "creation of a proletarian Red Army theater."[84] Piotrovsky was even less restrained. He announced that socialist society would be "theatrocratic." The lifting of financial considerations from theater circles had returned the element of "free play" to their performances.[85] Play would give birth to a new theater; and the theater would give birth to a new society. The theater should not be illusory, but a real thing; and there should be no spectators, just participants. Theatrical performance would lead to the creation of great festivals; and everyday life (byt ) would be remade there.[86]

Produced in the Bolshoi Opera, The Fire of Prometheus matched the pomposity of its locale. Piotrovsky and Radlov had learned little from their earlier collaboration on The Sword of Peace . The only extant description comes from an unsympathetic critic: "The first scene features Samson and Delilah; . . . the second features the Spartacus uprising; following this is a high-society ball in a setting that suggests the court of Louis XIV, mixed up with suggestions of other styles, including the . . . foot wrappings of one of the marquises. In the final act, after the heavens have parted, an amateur pair . . . dances a sultry Argentinian death tango.[87]

The Fire of Prometheus was a victim of its own ambitions. Amateur performances could not create both a new society and a new theater (assuming they could create either one). Konstantin Derzhavin, alluding to some of Kerzhentsev's claims, said that however wonderful "collective drama" was, it was not theater. Play is real; art is illusion.[88] Shklovsky conceded the value of play but added "such games [igrishcha ] have always existed, but nobody has called them theater. Theatricality [artifice] is essential to the theater."[89] Kuznetsov made perhaps the most telling observation on the limits of the form; play was a healthy sign in theater circles, but it could be of interest only to friends of the players. Such a presentation could not go beyond a limited audience.[90]

After the failures of The Sword of Peace and The Fire of Prometheus, Radlov rethought two theses that had thwarted mass productions: first, that "a spectacle performed for the broad masses must be a 'mass' spectacle in that a tremendous number of performers take part"; and, second, that "historical events instigated by a great quantity of people (such as a revolution) should be depicted in theatrical action by another great quantity of performers."[91]