Demythologizing Gold - Rush Labor

Few events in the history of the United States have been as glamorized by historians as the California Gold Rush. From the late nineteenth century to the present, most historians have portrayed it as both a heroic and dramatic epic and as a giant step toward the fulfillment of the nation's Manifest Destiny that presaged the full-fledged exploration and development of the Far West.

Even Carey McWilliams, hardly an ardent nationalist and indeed a man who devoted much of his scholarship to exposing the darker side of California's history, subscribed to much of the historical drama and mythology associated with the Gold Rush. Writing fifty years ago, he described the event "as one of the most extraordinary mass movements of population in the history of the western world." McWilliams argued that it was not simply the scale of the California Gold Rush that made it unique. It was "the first, and to date [1949] the last, poor man's Gold Rush in history." Influenced particularly by the anecdotes of men making fortunes in the early years, McWilliams described the Gold Rush as "the great adventure for the common man" and wrote of "this exceptional mining frontier [that] made for a real equality of fortune." He was not referring simply to the early years, however. McWilliams maintained that in California "unlike in other western mining states, the free miner remained, at least until 1873 or later, the foundation of the whole system." According to McWilliams, the placer mining of this period exemplified "democracy in production".[1]

The fact that even Carey McWilliams wrote about the Gold Rush and the Argonauts' experience in such neo-Turnerian language is testimony to the power of myth to influence historians' judgment. Traditional accounts have treated the Argonauts rather narrowly as adventurers who either failed or succeeded at the diggings; important aspects of the miners' larger social and labor history were thus overlooked

Hard work and perseverance bring success to a gold hunter in an illustration to The Idle

and Industrious Miner , a moralistic poem attributed to William Bausman. Published in

Sacramento in 1854, with wood engravings after designs by Charles Nahl, the allegorical

tale contrasts the disparate rewards attending vice and virtue. Despite the vivid imagery

of author and illustrator, good fortune in the diggings sprang more from good luck than from

good work habits. "Gold mining," as the witty Dame Shirley wrote her sister, "is Nature's

great lottery scheme." California Historical Society, FN-30967.

or treated in an incidental fashion. This is particularly true of the period from the mid-1850s to the 1870s, when gold mining was still important to the California economy but the rush years were over. With a few exceptions, not until relatively recently have historians of the Gold Rush begun to separate myth from reality in their work on the social history of the era.[2] Because California and western historians

were captivated by the myth and drama of the period, they were tempted to rely on the abundance of excellent anecdotal sources: diaries, memoirs, and letters, in particular, and, to an extent, newspaper accounts.[3] They used these sources at the expense of examining more objective statistical evidence to be gleaned from such sources as, among others, manuscript census data, passenger ship records, and reports and data generated by governmental agencies.

As Malcolm Rohrbough observes,.[4] Rodman Paul's California Gold ) (1947) was the first "modern" study of the California Gold Rush in that it made extensive use of quantitative sources as well as the more traditional ones.[5] While not totally neglecting social and labor history, Paul's work focused primarily on the business and technological history of California gold mining. The advent of the new social history during the 1960s eventually spawned a greater interest in the social history of California and the American West by a new generation of historians making much greater use of more objective statistical sources than their predecessors. Despite a few excellent works, however, we still lack a sufficient body of work on the social history of the Gold Rush to fill many of the gaps in our knowledge, and to definitively affirm, modify, or rebut some of the conclusions of the traditional accounts.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this essay examines the history of miners and their work during the gold-rush era (1848-1870), gleaning information from both old and new research on the subject. It explores questions central to understanding the labor history of this period: What impelled the mass migration of 300,000 people to California between 1848 and the mid-1850s? What were the living and working conditions of the miners? How and why did the Gold Rush generate episodes of nativism and racism that presaged and bedeviled the history of the Golden State far into the twentieth century? In particular, this essay explores how, between 1848 and 1870, the Argonauts were transformed from individual prospectors seeking (and sometimes obtaining) nuggets of gold from superficial placers into wage laborers employed by heavily capitalized hydraulic and quartz mining concerns in working conditions very much akin to those experienced by eastern workers in mid-nineteenth-century American factories. Rodman Paul noted this development in his seminal work fifty years ago, but several more recent studies of mining and miners in the American West, and, most notably, Ralph Mann's detailed study of Nevada City and Grass Valley during the gold-rush era, have significantly enhanced our knowledge.[6]

The proletarianization of the California mining labor force reflected a steady decline in the fortunes of most miners and large disparities in wealth and earnings between miners, merchants, and professional people in emergent towns such as Grass Valley and Nevada City. By the late 1860s, the result was growing social tensions between labor and capital. Influenced to a significant degree by the success of the Comstock Lode mining unions a few years earlier, miners conducted the first ma-

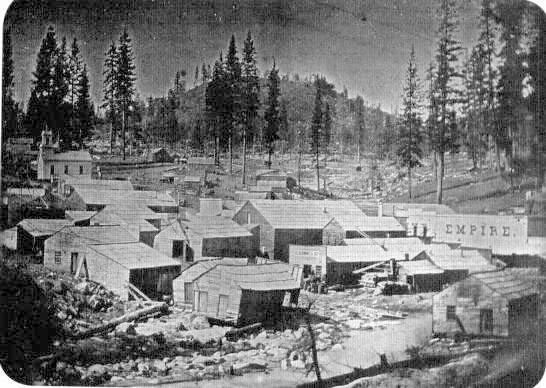

Nevada City in 1852, a rough, raw mining town built on the banks of Deer Creek, where gold was

found in the autumn of 1849. The rich placer deposits sparked a tremendous rush, and soon the

surrounding hills were covered with tents, brush shanties, and rude cabins. By late 1850 the

population had reached six thousand. That year several prospectors wrested a four-hundred-

pound lump of gold from the earth, but within the decade, miners were laborers and wage earners,

working for others rather than for themselves. Courtesy California State Library .

jor strikes in the California mining industry. They also founded the Golden State's first mining unions and resisted many of the concessions demanded by a new class of mining entrepreneurs.