4—

"We all live more like brutes than humans":

Labor and Capital in the Gold Rush

Daniel Cornford

Demythologizing Gold - Rush Labor

Few events in the history of the United States have been as glamorized by historians as the California Gold Rush. From the late nineteenth century to the present, most historians have portrayed it as both a heroic and dramatic epic and as a giant step toward the fulfillment of the nation's Manifest Destiny that presaged the full-fledged exploration and development of the Far West.

Even Carey McWilliams, hardly an ardent nationalist and indeed a man who devoted much of his scholarship to exposing the darker side of California's history, subscribed to much of the historical drama and mythology associated with the Gold Rush. Writing fifty years ago, he described the event "as one of the most extraordinary mass movements of population in the history of the western world." McWilliams argued that it was not simply the scale of the California Gold Rush that made it unique. It was "the first, and to date [1949] the last, poor man's Gold Rush in history." Influenced particularly by the anecdotes of men making fortunes in the early years, McWilliams described the Gold Rush as "the great adventure for the common man" and wrote of "this exceptional mining frontier [that] made for a real equality of fortune." He was not referring simply to the early years, however. McWilliams maintained that in California "unlike in other western mining states, the free miner remained, at least until 1873 or later, the foundation of the whole system." According to McWilliams, the placer mining of this period exemplified "democracy in production".[1]

The fact that even Carey McWilliams wrote about the Gold Rush and the Argonauts' experience in such neo-Turnerian language is testimony to the power of myth to influence historians' judgment. Traditional accounts have treated the Argonauts rather narrowly as adventurers who either failed or succeeded at the diggings; important aspects of the miners' larger social and labor history were thus overlooked

Hard work and perseverance bring success to a gold hunter in an illustration to The Idle

and Industrious Miner , a moralistic poem attributed to William Bausman. Published in

Sacramento in 1854, with wood engravings after designs by Charles Nahl, the allegorical

tale contrasts the disparate rewards attending vice and virtue. Despite the vivid imagery

of author and illustrator, good fortune in the diggings sprang more from good luck than from

good work habits. "Gold mining," as the witty Dame Shirley wrote her sister, "is Nature's

great lottery scheme." California Historical Society, FN-30967.

or treated in an incidental fashion. This is particularly true of the period from the mid-1850s to the 1870s, when gold mining was still important to the California economy but the rush years were over. With a few exceptions, not until relatively recently have historians of the Gold Rush begun to separate myth from reality in their work on the social history of the era.[2] Because California and western historians

were captivated by the myth and drama of the period, they were tempted to rely on the abundance of excellent anecdotal sources: diaries, memoirs, and letters, in particular, and, to an extent, newspaper accounts.[3] They used these sources at the expense of examining more objective statistical evidence to be gleaned from such sources as, among others, manuscript census data, passenger ship records, and reports and data generated by governmental agencies.

As Malcolm Rohrbough observes,.[4] Rodman Paul's California Gold ) (1947) was the first "modern" study of the California Gold Rush in that it made extensive use of quantitative sources as well as the more traditional ones.[5] While not totally neglecting social and labor history, Paul's work focused primarily on the business and technological history of California gold mining. The advent of the new social history during the 1960s eventually spawned a greater interest in the social history of California and the American West by a new generation of historians making much greater use of more objective statistical sources than their predecessors. Despite a few excellent works, however, we still lack a sufficient body of work on the social history of the Gold Rush to fill many of the gaps in our knowledge, and to definitively affirm, modify, or rebut some of the conclusions of the traditional accounts.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this essay examines the history of miners and their work during the gold-rush era (1848-1870), gleaning information from both old and new research on the subject. It explores questions central to understanding the labor history of this period: What impelled the mass migration of 300,000 people to California between 1848 and the mid-1850s? What were the living and working conditions of the miners? How and why did the Gold Rush generate episodes of nativism and racism that presaged and bedeviled the history of the Golden State far into the twentieth century? In particular, this essay explores how, between 1848 and 1870, the Argonauts were transformed from individual prospectors seeking (and sometimes obtaining) nuggets of gold from superficial placers into wage laborers employed by heavily capitalized hydraulic and quartz mining concerns in working conditions very much akin to those experienced by eastern workers in mid-nineteenth-century American factories. Rodman Paul noted this development in his seminal work fifty years ago, but several more recent studies of mining and miners in the American West, and, most notably, Ralph Mann's detailed study of Nevada City and Grass Valley during the gold-rush era, have significantly enhanced our knowledge.[6]

The proletarianization of the California mining labor force reflected a steady decline in the fortunes of most miners and large disparities in wealth and earnings between miners, merchants, and professional people in emergent towns such as Grass Valley and Nevada City. By the late 1860s, the result was growing social tensions between labor and capital. Influenced to a significant degree by the success of the Comstock Lode mining unions a few years earlier, miners conducted the first ma-

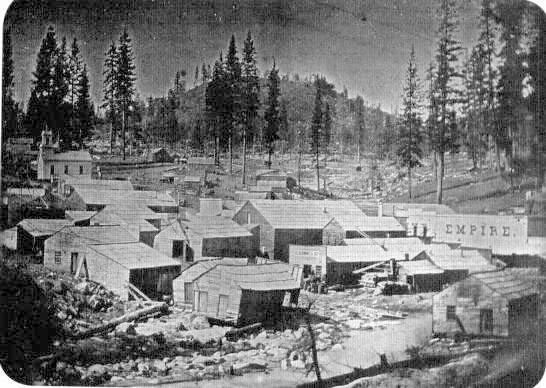

Nevada City in 1852, a rough, raw mining town built on the banks of Deer Creek, where gold was

found in the autumn of 1849. The rich placer deposits sparked a tremendous rush, and soon the

surrounding hills were covered with tents, brush shanties, and rude cabins. By late 1850 the

population had reached six thousand. That year several prospectors wrested a four-hundred-

pound lump of gold from the earth, but within the decade, miners were laborers and wage earners,

working for others rather than for themselves. Courtesy California State Library .

jor strikes in the California mining industry. They also founded the Golden State's first mining unions and resisted many of the concessions demanded by a new class of mining entrepreneurs.

Why They Went

While mythology and hyperbole surround the California Gold Rush, it would be no exaggeration to say that it was one of the largest occupational migrations of labor in American history. The number of people engaged in mining skyrocketed from 4,000 in 1848 to about 100,000 by 1852 and stayed at that number until the late 1850s.[7] An

even better indication of the importance of mining is obtained by calculating the proportion of the work force engaged in mining. In 1850, almost 75 percent of all employed men in California (57,797 of 77,631) were miners.[8] As late as 1860, when mining had declined in importance in absolute and relative economic terms, the federal census data reveals that miners still made up 38 percent of the California work force (82,573 of 219,192).[9]

Historians have yet to explain convincingly why some people succumbed to the lure of gold and others did not. Undoubtedly, people with some previous experience of mining were eager to employ their skills in California. They included base-metal miners from the British Isles, especially Cornwall, and men from the gold and silver regions of such countries as Mexico, Chile, and Peru, as well as some who had participated in the earlier gold rushes in North Carolina and Georgia and the lead mining boom in the upper Mississippi Valley.[10] But these miners made up a relatively small fraction of the migrants.

Insofar as generalizations can be made about the forces that propelled this mass migration, historians have pointed to improvements in transportation, the expansion of global trade networks in the mid-nineteenth century, and the emergence of a "mass" press in many countries that was only too eager to stir up gold fever. For example, news of the Gold Rush reached Cornwall before it arrived in northern Michigan.[11] Historians have also argued that the discovery of gold in California coincided with the continuing decline of agriculture in many parts of the northeastern United States, and that other workers were increasingly faced with the prospect of working for a subsistence existence in the burgeoning factories and workshops of America's major cities. Whether they were struggling to maintain a farm or working a twelve-hour day for not much more than a dollar a day in a textile or shoe factory, some found the lure of gold irresistible.[12]

Other historians, such as David Goodman, have maintained that the wide acceptance of ideas associated with a pervasive laissez-faire political ideology in the mid-nineteenth century played an important role. Moreover, according to Goodman, an emergent "equalitarian republicanism" reconciled an ideology of self-aggrandizement with the growing imperial aspirations of the nation. In short, the ideology of laissez-faire legitimated, even encouraged, the single-minded pursuit of wealth at all costs and thus made many people susceptible to gold fever.[13] It is, however, dangerous to explain the exodus to California in mechanistic terms of the stages of American (or world) economic development and associated ideologies.[14] As one of the leading historians of the California Gold Rush has observed with reference to an earlier era of American history, "the agrarian frontiers shared with the mining frontiers a persistent American restlessness, an equally pervasive addiction to speculation and a desire to exploit virgin natural resources under conditions of maximum freedom."[15]

In all likelihood a person's propensity to emigrate to California had as much to do with mundane practicalities as it did with the forces of national or world economic development. Proximity to ports and sources of transportation in general was almost certainly a significant factor. As important was the ability of the prospective Argonaut to raise sufficient capital to make the journey and to become established in the diggings. In 1848 and 1849 the cost of the ocean voyage from the East Coast via either Cape Horn or the Isthmus of Panama ranged from $300 to $1,000. Overland travel required approximately $300.[16] Although the journey could be completed for $300, this was a significant, even prohibitive, sum for many farmers and workers in the East whose annual income rarely exceeded this amount. Even if pooling capital in joint-stock companies and borrowing money from family networks helped offset financial obstacles to migration,[17] probably only a small portion of ordinary workers and farmers caught in an emergent industrial revolution could avail themselves of the opportunity of joining the Gold Rush. Few of those who came were among the abject poor.

There is, of course, less uncertainty about the motivation of the Argonauts. Although, as David Goodman has pointed out, people like Henry David Thoreau and more traditional elements of society such as the church, had some grave reservations about such single-minded pursuit of wealth and its consequences, these people were in a minority.[18] As Ralph Mann succinctly put it, "the California Gold Rush was not an aberration in nineteenth century American history, nor were the Forty-Niners alienated from the values of their time."[19] The Gold Rush promised "opportunities and experiences approved by their society—even identified by it as uniquely American."[20] In the words of another historian, the event represented "an image of instant success available through hard work; an affirmation of democratic beliefs under which the wealth would be available to all."[21] To those who felt guilt at leaving their families or had some reservations about the pursuit of wealth for its own sake, qualms could be allayed by the ethnocentric belief that they were also serving the higher purpose of fulfilling the nation's Manifest Destiny. In an address to the Society of California Pioneers in 1860, Edmund Randolph was enraptured at the thought of

California in full possession of the white man, and embraced within the mighty area of his civilization! . . . We see in our great movements hitherward in 1849 a likeness to the times when our ancestors . . . poured forth by nations and in never-ending columns from the German forests, and went to seek new pastures and to found a new kingdom in the ruined provinces of the Roman Empire.[22]

While the pursuit of wealth was undoubtedly the migrants' predominant motivation, one of the great paradoxes of the Gold Rush is that the attainment of this end required almost unprecedented levels of cooperation between strangers, such as

the formation of joint-stock companies for the journey and similar ventures at the diggings to build dams, sluices, tunnels, and the like. But the longer-term impact of this spirit of cooperation should not be exaggerated. One miner put it this way: "The people have been to each other strangers in a strange land. Absorbed in this eager pursuit of wealth, they have not taken time for the cultivation of those affinities which bind man by a higher and holier tie than mere interest."[23] He stressed that the expectation of most miners that their visit to California would be a temporary one resulted in an "almost total lack of social organization."[24] Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that, even as independent miners were reduced to the status of modestly paid wage laborers employed by hydraulic and quartz mining companies, collective activity in the form of strikes or unions was late in arriving in the California mining industry.

Different Labor Systems, Diverse Gold Seekers

Not all miners, even in the early phase of the Gold Rush, were freewheeling independent entrepreneurs. As Susan Johnson has put it, "work in the diggings proceeded according to a dizzying array of systems that included independent prospecting and mining partnerships as well as altered Miwok gathering practices, Latin American peonage, North American slavery, and, later, Chinese indentured labor."[25] In the case of African Americans, a significant number of free blacks joined the Gold Rush. Some were seamen deserting vessels arriving from New England ports, while others made their way to California as employees or servants of overland joint-stock companies. But just as commonly, African Americans arrived in California as slaves to their gold-seeking masters. Rudolph Lapp estimates that 962, or approximately 50 percent of the African Americans in California in 1850, were slaves.[26]

We will never know precisely how many of the at least 15,000 Mexicans (10,000 from the province of Sonora alone) came as unfree laborers sponsored by patrones . Leonard Pitt asserts that "the north Mexican patrons themselves encouraged the migration of peons by sponsoring expeditions of twenty or thirty underlings at a time, giving them full upkeep in return for half of their gold findings in California."[27] The patrón system was also responsible for bringing a certain (unknown) proportion of miners to the diggings from Chile and Peru.

The Chinese did not arrive at the diggings quite as early as the Mexicans and South Americans. In 1850 there were only 500 Chinese miners in California, and 1,000 Chinese people in the entire United States.[28] However, in 1852 alone, 20,000 Chinese people entered California, most of them en route to the mining counties. By one contemporary estimate there were 20,000 Chinese miners in California by 18557.[29] Many of the first Chinese migrants were merchants able to pay their way from China. Others were not so fortunate. Most of the Chinese who emigrated to the United

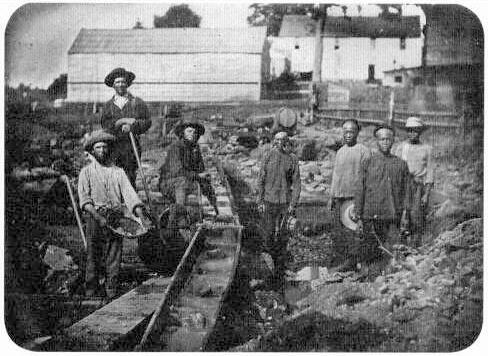

American and Chinese miners work a claim at the head of Auburn Ravine with a line

of sluice boxes in 1852. Woods Dry Diggings, as Auburn was originally named, was

one of the earliest mining camps in California, established in May 1848 when Claude

Chana and a party of Indians discovered gold in the ravine. Chinese merchants

contributed to the growth of the town, and several of their old wooden shops, dating

to the year of this daguerreotype, still stand on Sacramento Street. Courtesy California

State Library .

States did not experience the exploitation of the notorious "coolie" system, which bound workers to sign contracts agreeing to work in a foreign land for a specified time in return for their passage. Instead, most Chinese workers paid for their passage by what Sucheng Chan calls the "credit-ticket system," whereby Chinese middlemen paid the passage of emigrants in advance. In return, the emigrants contracted to pay their debts after arrival, with the prospect that the emigrants could keep their earnings after debts were paid.[30] While more research is needed to determine more precisely what proportion of Chinese emigrants arrived under the credit-ticket system, historian Elmer Sandmeyer asserts with confidence that "the evidence is conclusive that by far the majority of Chinese who came to California had their transportation provided by others and bound themselves to make repayment."[31] Indeed, the consensus of other historians is that the labor of indebted passengers was sold through Chinese subcontractors to Chinese mining companies, although some describe the labor system and working conditions of these Chinese as akin to debt peonage.[32]

In part, as Leonard Pitt has argued, the "free labor" preferences of white Americans contributed to the xenophobia and racism that most foreign miners (as well, of course, as Native Americans and Californios) encountered.[33] But there were other reasons why white American-born miners often had no compunction about expelling foreign miners, especially racial minorities, from the diggings and from mining towns. First, the American miners, conscious of the fact that access to gold was limited, resented the fact that the mining experience of peoples from Mexico, Chile, and Peru often made them more successful prospectors. Second, the belief in Manifest Destiny, reinfused by the United States's victory in the Mexican-American War, led many Americans to presume that they had priority at the diggings. Third, even while hostility and violence were also directed at white foreign nationals such as the French and Australians, the depths of racist ideology cannot be overemphasized. Indeed, as more and more historians have demonstrated, racist ideology was a crucial building-block in the making of white working-class consciousness.[34] Finally, as wage labor became more and more common in the mines, the disillusioned American Argonauts resented the competition of cheaper "foreign" labor. This contributed to the expulsion of many Native Americans in the early gold-rush years and was a source of tension between white and Chinese miners throughout the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s.[35]

In general, minorities suffered most from extra-legal forms of violence, but in the early 1850s white miners had the political clout to impose "legal" forms of discrimination on their rivals. This came in the form of two foreign miners' tax measures that were passed by the state legislature. The first, enacted in 1850, required miners who were not citizens of the United States to pay a licensing fee of $20 a month. Targeted particularly at Mexicans, this measure led to violence and the eventual departure of about 10,000 Mexican miners to their homeland in 1850.[36] The protests of many American merchants who lost customers as a result of the measure led to its repeal in 1851, but the influx of Chinese in 1852 prompted the passage of another act that provided for a tax of $3 per month, later raised to $4.[37]

While not a target of foreign miners' taxes, Native Americans suffered extreme violence at the hands of Argonauts from many nations. California Indian labor played a particularly important role in the early gold-rush years. The best estimate is that by the summer of 1848 perhaps half of the 4,000 miners were Indians. Even before the Gold Rush, Anglo-Americans and other immigrants in Hispanic California were quick to imitate the Mexican system of Indian labor exploitation. A group of pioneers such as John Sutter and John Bidwell simply moved their Indian labor force from their ranchos to the mines. There were reports of individual whites employing up to one hundred Indians at the diggings.[38]

Not all Indians worked for whites. Some were independent miners who bartered their gold dust with merchants on increasingly favorable terms as they came to ap-

preciate the value that the white man attached to it. But the Indian presence as independent and employed miners was short-lived. As Albert Hurtado and others have shown, newly arriving white miners from Oregon and other parts bitterly resented the advantage that ranchero employers of Indians had. Starting in 1849, and using indiscriminate and extreme violence, they drove most Indians from the mines. The 1852 state census showed that, with the exception of the southern mining counties, Indians made up a relatively small proportion of the population of the mining counties. Outside the southern mining counties, they constituted less than 10 percent of the population in every mining county but one. In these counties, probably only a small proportion of the Indians still present worked in the mines, and in most cases, historians agree, they usually worked for white miners. In the Southern Mines the Indians' numerical superiority prevented whites from driving them out during the early 1850s, but in time "attrition caused by disease, gradual displacement, and only occasional fighting would make the south a white man's country."[39]

Life and Labor at the Diggings

Unquestionably, the ability to employ slaves, peons, or indentured labor gave some miners an advantage. However, the circumstances of the early gold-rush years made, to some extent, for the appearance of a degree of equality, or at least equality of opportunity, among the majority of miners. In the period where superficial placer mining predominated, most miners had access to the capital necessary for such mining. Furthermore, some early mining tools, such as the cradle, which required more than one person to operate, fostered a spirit of unity and cooperation among miners. But, most importantly, success at the diggings in the early years was as much a matter of luck as anything else. As Dame Shirley succinctly put it, "gold mining is Nature's great lottery scheme."[40]

The fact also that miners dressed almost identically helped blur class distinctions. "Their heavy boots, sturdy trousers, checked shirts, large belt, slouch hat, and gloves formed a uniform worn by miners up and down the Sierra that made them indistinguishable from one another," says historian Malcolm Rohrbough in his recent study.[41] Moreover, he adds, the miners "wore their uniforms with pride. Their dress was a badge of members in a large fraternity and it established their status as workers."[42] In addition, the miners' hostility to other occupational groups, such as merchants, teamsters, boardinghouse keepers, doctors, and lawyers, on whom they depended at times, reinforced the miners' identity of themselves as workers.[43] One observer at a boardinghouse for miners summarized the situation as follows: "The wondrous influence of gold seem to have entirely obliterated all social distinctions."[44]

The sheer hard labor entailed in most forms of early placer mining also contributed to weakening class identities. Rodman Paul describes the work as "most

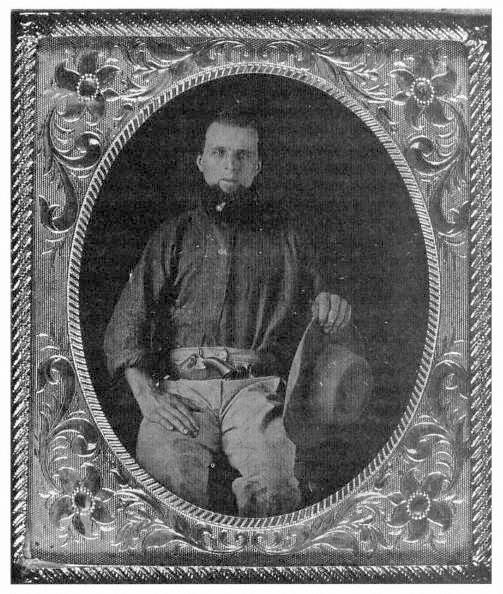

The Forty-niner Solomon Yeakel set out for the new El Dorado at the age of twenty-one,

crossing the Plains and the Rockies to seek his fortune. Like most Argonauts, Yeakel returned

home rather than settle in California. He later enlisted in the Pennsylvania Volunteers and

fought at the Battle of Bull Run. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

nearly akin to ditch digging."[45] In 1848 and 1849, most independent miners worked the diggings as individuals or with their families. By 1850, as placer mining required a cradle and the building of dams and sluices, miners formed themselves into companies of four to eight men. While usually the tasks were rotated, the labor was grueling. Work was often performed in ice-cold water generated by the melting snow, even while in the sun's glare summer temperatures not uncommonly reached 100 degrees. The workday generally began at 6 A.M. There was a break around noon for a couple of hours to escape the worst of the sun and eat lunch, then work resumed until sunset. The physical exigencies of mining may be gauged from the fact that by one estimate, even in 1849 when the yields were good, miners needed to wash an average of 160 buckets a day to acquire one ounce ($16) of gold.[46] "You can scarcely form any conception of what a dirty business this gold digging is and of the mode of life which a miner is compelled to lead," wrote one miner. "We all live more like brutes than humans."[47] The seasonal nature of the work added to the miners' sense of urgency. In the Northern Mines, work was possible most years only from July through late November. Heavy rains and snow made work impossible for the rest of the year. One option for miners was to move during winter and spring to the Southern Mines and engage in the "dry diggings." However, stresses Rodman Paul, while "the yield of the dry diggings during the winter months was often large . . . the period of effective operations was short, and the chances were extremely dependent up on the weather," especially a sufficient flow of water during the spring months.[48]

The almost complete absence of women at the diggings forced men to learn a wide range of domestic skills, including sewing, washing, and, of course, food preparation. Some men had acquired these skills on the overland trail, but many had not, and not until the advent of boardinghouses and an assortment of domestic-related service industries in mining towns were the majority of miners relieved of such chores.

In 1850, less than one-tenth of the population of California was female, according to the census, and in the mining counties women made up only 3 percent of the inhabitants.[49] While they made up 30 percent of the California population by the 1860s, they continued to be as small a proportion of the population in the mining counties as they had been in 1850. Small wonder that even in established mining towns such as Grass Valley and Nevada City only one in ten men was married in 1860, and among miners only one in twenty-five was betrothed.[50]

This small female population engaged in a variety of occupations. In 1848, American families and migrant families, especially from Sonora, encamped near the diggings and undoubtedly women panned for gold. However, there is little evidence that women participated in the diggings in significant numbers for very long.[51] Yet the female population of the mining counties engaged in a wide range of occupations. Some women worked as prostitutes in the mining towns,[52] while others were

Having dammed the river and turned its torrents into a flume, miners burrow deep into its bed,

laboring with picks and shovels to win the riches of ancient Tertiary deposits. Beginning work

at dawn, laboring six or even seven days a week, often in icy waters or under a burning sun,

Argonauts occasionally lost all sense of time in an exhausting round of never-ending physical

exertion. "Digging for gold," as one miner put it, "is the hardest work a man can get at."

California Historical Society, FN-04135 .

employed in the entertainment industry as dance hall girls and singers. But women also worked in many other occupations that do not fit the popular stereotypes of female employment during the Gold Rush. Ralph Mann's study of Grass Valley and Nevada City provides us with the most definitive evidence. Mann's data show that the townswomen from these two cities engaged in fifteen different occupations. In both places, two-thirds of employed women cared for boarders. Women also worked as servants, seamstresses, dressmakers, shopkeepers, cooks, bakers, washerwomen, boardinghouse operators, and by 1870 in a few cases, as schoolteachers.[53]

There is a lack of consensus about the quality of the miners' diet. Some overlanders and miners such as William Swain ate well and found food a major compensation for their many other drudgeries.[54] While lines of supply in the early gold-rush years were not always reliable, historian Joseph Conlin asserts that "grocers reached most camps before the prostitutes did."[55] Nevertheless, in the early years the basic diet of meat, bread, or biscuits washed down with tea or coffee was not always supplemented with fresh fruit and vegetables. The very high price of food sometimes caused the miners to cut corners on their diets, and a few unfortunate ones may have starved. Rodman Paul concludes that in 1849, and for some of 1850 at least, partially

as a result of dietary deficiencies, "many suffered from diarrhea, dysentery, scurvy, and other debilitating diseases," although, he argues, the situation quickly improved during the 1850s.[56]

The primitive dwellings that were hastily erected in clusters as close to the diggings as possible did not contribute to the health of miners but instead abetted the spread of disease. Some early miners built log cabins, but most lived in rudimentary canvas tents that they usually abandoned during the winter.[57] As the 1850s progressed, the situation improved, as mining towns such as Grass Valley and Nevada City sprang up with regular boardinghouse facilities. However, before 1870 a majority of miners in both places lived in cabins,[58] and in more isolated areas miners continued to occupy fairly primitive cabin dwellings until much later.[59]

Accidents at the mines were commonplace from the outset, but as mining became more technologically advanced, the potential for serious accidents increased.[60] The growing use of tunneling and gunpowder, in particular, took its toll. While the issue of gunpowder contributed to the first major labor strike in the California mines, the legislature showed little interest in passing any protective legislation for miners during the nineteenth century. In this respect California was hardly atypical. In the most recent book on the history of occupational safety, Mark Aldrich, after describing a fatal mining accident in West Virginia in 1898, concluded that "most managers, and probably most Americans, if they thought about these matters at all, would have deemed such deaths individual tragedies for which the company bore little, if any, responsibility."[61]

By any standard, miners were highly itinerant workers. In the space of the five-month mining season, miners might explore several different claims. They might move within their mining region or between the northern and southern mining areas. They might also depart for another rush such as the Comstock rush of 1859 or the short-lived rush on the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1858. Winter forced many miners into the towns of Marysville, Sacramento, Stockton, and, of course, San Francisco, where many searched for work. But even during the mining season, poverty, disillusionment, or the need to reprovision caused miners to move back and forth between the diggings and the cities. By the early 1850s, the appearance of well-equipped stores and full-fledged mining towns in some areas eliminated some of the causes of transience.

Mann's study, however, indicates that even as mining camps evolved into well-developed towns, rates of geographical mobility remained high throughout the period between 1850 and 1870. Mann found that in both Nevada City and Grass Valley only 3 percent of the miners recorded in the 1850 census were still there in 1860.[62] During the 1860s, the persistence rate of miners was not much higher. Only 5 percent of those appearing in the 1860 census for Nevada City could be found in the census of 1870, while the persistence rate for Grass Valley was only 6 percent.[63] If the communities of Grass Valley and Nevada City are taken as a whole, only one in ten of

Seated before a rude cabin roofed with canvas, a solitary Argonaut plays his flute, filling

the evening air at Boston Flat with music, in a daguerreotype by H. M. Bacon. In addition

to enduring hard labor and bad food, homesickness and disease, the Argonauts often spent

their nights and dreary rainy days under the most miserable of conditions. "We all," as one

miner wrote his sister in 1850, "live more like brutes than humans." Courtesy Society of

California Pioneers .

the population of both towns continued their residence between 1860 and 1870. While the turnover rate in many other American towns and cities was high, especially on the frontier, Mann's comparative data indicates that the turnover of populations in Grass Valley and Nevada City was exceptionally high. Even turbulent San Francisco experienced a persistence rate of 25 percent between 1850 and 1860. Persistence rates for other studied frontier communities have varied from 25 to 60 percent over the course of a given decade.[64]

Historians studying social and geographic mobility have long pondered the relationship between the two without drawing definitive conclusions about why some people settled down and others did not. High rates of geographic mobility may indicate that people were "pushed" from communities by limited opportunities for advancement. Alternatively, it may show that people were pulled away from their

communities by the prospect, and actuality, of greater opportunity. The higher rates of persistence of people with professional or high-paying occupations leads most historians to believe that itinerant workers were, in general, more likely to be pushed than pulled.

Perhaps this was not the case with the Argonauts, eternal optimists ready to move on to the next site on the flimsiest of rumors. Whether hopes and expectations were borne out by reality, however, is quite another question. Moreover, it must be noted, increasingly during the 1850s, the miners' status was changing from independent prospector to permanent wage laborer.

From Argonauts to Wage Laborers

The glory days of the lucky, individual Argonaut were very short-lived. By the early 1850s, even the expedient of pooling capital with fellow Argonauts barely enabled most miners to retain a vestige of their independence. Increasingly, during the 1850s, miners were forced to work as wage laborers for large corporations often employing several hundred men. Although reliable statistical data is not available, it would be safe to say that by the late 1850s, a substantial majority of miners were wage laborers. While the corporations probably employed a significant number of the early Argonauts who remained at the diggings, they also began to hire a large number of men with considerable experience in mining, especially from the British Isles. In short, in the space of a few years the noble and adventurous Argonaut had been reduced to the status of a proletarian working for wages and in conditions not much better than factory workers in the East.

Unquestionably, some miners, especially those arriving between 1848 and 1850, struck it lucky. The majority, however, did not, and "wages," defined either as earnings from the work of individual prospecting or wage labor, declined sharply from 1848 onward. Conceding the lack of totally comprehensive and reliable data, Patti estimates that the miner's "wage" declined from $20 per day in 1848 to $10 per day in 1850, to $5 per day by 1853, and to $3 per day in the late 1850s.[65] Notwithstanding the fact that the decline in wages was offset by a decline in the cost of living, it appears that the miners' real wages declined significantly between 1848 and 1860.

Mann's detailed statistical data also support such a conclusion. He found that in Grass Valley and Nevada City only one out of ten miners reported owning real estate or personal property at the time of the 1860 census. By contrast, one-half of the two towns' businessmen reported over $1,000 in real estate and personal property.[66] Small wonder that Mann concluded that "in a disproportionate number of . . . cases the man was a propertyless miner. . . . No longer living in camps, hoping to strike it rich, they now dealt in embryonic industrial slums, hoping for a living wage. The gap between miners and the rest of society was more than spatial; they were much less

likely to own their own homes, have families, or accumulate possessions."[67] While by 1870 things had improved for a relatively small core of more skilled miners, 75 percent or more of them in both towns still reported no personal or real estate.[68]

How had it come to pass that the ever-optimistic Forty-niners, hopeful of finding their fortunes, or at least enough money to buy farms back East, had been reduced to such lowly status and economic standing? By the early 1850s, external and inexorable forces were impinging on the miners' chances of succeeding as individual prospectors. After the easy pickings from the superficial placers had been exhausted, more elaborate and capital-intensive technologies had to be employed to extract gold. Initially, Argonauts were able to pool their capital and labor to acquire and use rockers and to build dams and sluices necessary to the more advanced forms of placer mining. If the miners' capital was not sufficient, local merchants often subscribed to the joint-stock companies.[69] However, during the 1850s, the scale of hydraulic mining projects increased, necessitating a growing reliance on both wage labor and external capital.

In 1853, it was reported that nearly twenty-five miles of the Yuba River had been diverted at a cost of $3 million.[70] A single construction project could, by the mid-1850s, cost as much as $120,000, and as many as 260 men might be employed on it.[71] The scale that hydraulic mining assumed may be gauged from the following statistics. By 1857, 4,405 miles of canals, ditches, and flumes had been constructed at a cost of about $12 million.[72] With investments on this scale by the late 1850s, "the new owners were what contemporaries called 'capitalists,' and the operation of this process sometimes meant a transfer of control from the working men in the foothills to the business and financial men in the cities."[73] Or, as Ralph Mann put, it "for many men the fortunes of the mining company became the fortunes of the company that employed them."[74]

Also requiring large investments of capital, and threatening the independence of miners, were the quartz mines of the early 1850s. These mines attracted a significant amount of eastern and English capital.[75] As early as 1851, there were twenty quartz mines in operation in Grass Valley and Nevada City,[76] and by 1852 Grass Valley residents claimed that the Gold Hill mine had yielded $4 million in gold.[77] The quartz companies employed men for $100 a month and found plenty of Argonauts willing to sacrifice their independence.[78]

While the quartz mining boom of the early 1850s fell far short of investors' expectations,[79] hardrock mining became more widespread and stable during the late 1850s. In 1855 there were only thirty-two quartz mines in the state, but by 1857 there were as many as 150 and a larger number of stamp mills and arrastras for extracting the gold from the quartz.[80] By 1870, quartz mining accounted for 31 percent of the dollar value of all gold mined in California.[81] Quartz mining became well established

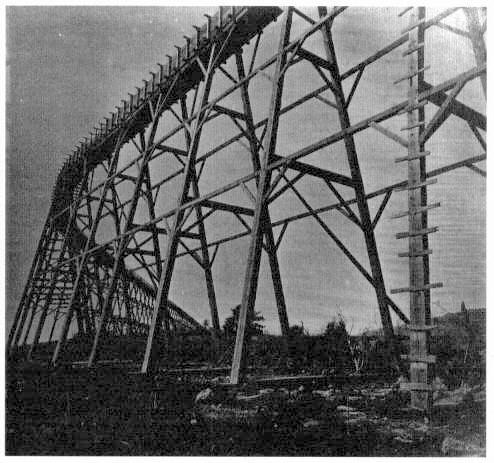

A flume carries water for hydraulic mining at Smartsville, Yuba County, about 1865.

Beginning with the rise of hydraulicking in the mid-1850s, an enormous water-delivery

network arose in the Sierra Nevada, and by the end of the decade nearly seven thousand

miles of flumes, canals, and ditches had been constructed to serve mining companies

in the Golden State. Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

in some towns like Grass Valley, where by the 1860s as many men were employed in quartz mining as in hydraulic mining.[82] Mann suggests several reasons for the expansion and success of quartz mining in Nevada County. First, many entrepreneurs and miners acquired much invaluable technical knowledge from their experience of quartz mining at the Comstock Lode. Second, there was a large supply of capital from the eastern states and Europe to finance this expansion. Third, an increasing influx of skilled Cornish miners, in particular, furnished the expertise to work these mines profitably.[83]

The Miners Fight Back: Strikes and Unions

Not until the late 1860s, and with the ascending importance of quartz mining, did anything resembling a "labor movement" emerge in California mining. Prior to 1869, when the first union was formed and the first major labor strike occurred, strikes appear to have been sporadic.[84] Why were there so few strikes in the gold mines and why did it take over twenty years for the first labor union to appear? First, even as the days of the independent prospector came to an end and the era of wage labor began, miners continued to be itinerant. This was not conducive to strikes and certainly not to the building of unions, especially among workers, a substantial majority of whom saw their stay in California as temporary. Like many disgruntled workers in other industries with a highly mobile work force, miners tended to strike with their feet and simply move on to the next camp or mine. Second, the relative isolation of the work setting made it hard for miners to coordinate a strike effort or to build a union. Furthermore, in these isolated settings workers could not call on the support of the community, a factor that was crucial to the success of later strikes and unions. Third, deep-seated ethnic, racial, and national animosities among the diverse workers were inimical to the waging of strikes and the building of unions. Fourth, until the 1860s, absentee mine ownership was uncommon. Quite often the owner was also a manager and therefore, in the eyes of the worker, a fellow member of the "producing classes," and one who often risked considerable capital to put men to work. Finally, while a vibrant labor movement had existed at times during antebellum America (especially during the Jacksonian era), the movement was episodic and the majority of American workers had had no experience of strikes or trade unions.

It is significant that strikes and unions in California gold mines occurred after the first successful organizing wave by hardrock miners at the Comstock Lode in Nevada and that the major conflicts occurred at quartz mines employing a relatively large number of miners. Many California miners joined the Comstock rush in the early 1860s, and many returned within a few years. In some cases these returning men played a key role in sparking strikes and building unions in California. At the very least, historians are agreed that the success of the labor movement in the Comstock mines was a major influence in spurring the development of labor militancy and unionism among hardrock miners all over the American West.[85]

Experienced Cornish workers played a particularly important role in the development of western mining and also in the building of a labor movement. By the third quarter of the nineteenth century, immigrants from the British Isles comprised approximately half the work force in many of the hardrock mining centers of the West, such as Grass Valley.[86] They were roughly evenly divided between Irishmen and non-Irishmen, most of whom were from Cornwall. The Cornish miners

had been encouraged to emigrate because of the serious decline of the centuries-old regional tin industry. Sometimes they emigrated to other regions of the United States to mine coal or other ores before coming to California; sometimes they migrated directly.

Exceptionally clannish, the Cornish had a fierce pride in their long-standing craft traditions and skills. Indeed, no group of miners was more prized for their skill by mining employers than were the Cornish in the latter half of the nineteenth century. It was in some ways ironic that the Cornish should be thrust into the vanguard of the union movement among miners in the West. The Cornish did not bring with them any traditions of trade unionism from the British Isles, but rather a tradition of fierce individualism. What thrust the Cornishmen into the forefront of the western mining labor movement was the fact that soon after their arrival new mining technologies began to threaten their craft traditions and workplace prerogatives.

The cause of the first major strike in the California gold mines, which occurred in Grass Valley in 1869, is illustrative.[87] A series of issues, including Sinophobia, demands for higher wages, and the objection of Cornish miners, in particular, to the use of dynamite and new drilling practices, precipitated the strike. By 1870, three-quarters of all adult men in Grass Valley were foreign born, and slightly over half of these were British, most Cornish.[88] The Cornish miners were accustomed to working in pairs as "double-handed" drillers. One would wield the hammer while the other held and twisted the drill bit. By the 1860s, some employers saw this as a wasteful use of labor and advocated single-handed drilling. Employers also began to insist that miners use dynamite, or "giant powder," as it was called, instead of the less powerful and volatile "black powder." The Cornish miners insisted that this new gunpowder produced noxious fumes and refused to use it. The situation was further complicated and inflamed by mining employers' threats to hire Chinese workers as single-handed miners using the new explosives. All this occurred in the context of a situation where quartz miners' wages had been reduced to three dollars per day or less, and in which mine owners were trying to crack down on the practice of high-grading. High-grading was the name given to the miners' habit of privately helping themselves to promising lumps of quartz, apparently a common practice before the 1860s.

The catalyst for this first strike was the decision of one mine in Grass Valley to change over exclusively to the use of dynamite and to allow only single-handed drilling. In April 1869, other mining employers followed suit, and soon several hundred miners went on strike in protest. The miners decided to form a "branch league" of the Comstock unions and asked the Nevada miners to send them an organizer. The striking miners resolved not to use the new powder or allow single-handed drilling, and they pledged that no one would work underground for less than three dollars per day. The employers attempted to hire scabs, but with very little success.

Faced with the solidarity of the miners, who had much community support, most mine owners accepted the union's terms by July, and within a few months the union boasted seven hundred members.[89]

Further conflict between labor and capital was not long in spreading. The quartz mines of Amador County were one locus of discontent.[90] Again many issues were involved in the dispute, but when one company cut wages to two dollars a day, the "Amador War," as it became known throughout the state, was on. The miners formed themselves into the Amador County Laborers' Association, which soon claimed four hundred members. Like the miners of Grass Valley, the Amador men were determined not only to improve their wages, but also to exclude, as far as possible, the employment of Chinese in the mines.

By 1871, as the strike dragged on, the Amador War had become a state issue. The attempt of California governor Henry Haight to use the state militia to break the strike was almost comically inept and ineffective. With the exception of negotiating a daily minimum wage of three dollars for surface and mill workers, the union eventually won all its demands.[91]

Several other major mining strikes occurred in the early 1870s. While California gold miners' opposition to giant powder weakened, as it did everywhere, the labor movement in the California mines was, like the Comstock unions, effective not in bringing about great improvements in miners' conditions, but at least in holding back employers' attempts to further erode the miners' working conditions and prerogatives during the late 1860s and 1870s. Richard Lingenfelter attributes their success to the "internal solidarity of the unions and their strong support within the community," as well as to the fact that a significant group of miners now felt a sense of permanence in their communities.[92]

Little study has been devoted to California gold miners after the 1870s that might reveal whether their unions retained power. It seems likely, however, that the gradual decline of the California gold industry eroded the strength of the miners' position. In the early years of the twentieth century, miners in most western states obtained the eight-hour work day, but not in California. Mark Wyman quotes the president of the Tuolumne Miners' Union, who in 1900 said that, as far as miners were concerned, California "was the poorest organized state in the West."[93] He added that miners had not won employer agreement to limitations of the workday or bans on compulsory hospital fees. Finally, in 1909, the state passed an eight-hour-day law for miners.[94]

It seems likely that the decline in California gold mining weakened the hand of the miners in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Miners simply no longer had the numbers to intimidate scabs and the state militia, or to influence the state legislature in the way that miners were able to do in many other western hardrock states. Instead, if we are to believe Rodman Paul, many California gold miners, both

quartz and hydraulic ones, eked out an existence during the late nineteenth century in rather isolated company towns where their power was limited.[95] Whatever the case, Paul's judgment is sound when he asserts that "within the short span of twenty-five years California mining had passed through a cycle that commenced with what economists call 'home crafts' and ended with what socialists term 'proletarian industry.'"[96]