Chapter Thirteen—

The Lower Klamath Fishery:

Recent Times

Ronnie Pierce

During the 1800s, progressive white settlement of California had drastically disrupted Indians' lives. One event at the close of that century had a tremendous effect on the Klamath/Trinity fishery: in 1894 a through road from Eureka to Crescent City was completed, and it crossed the Klamath estuary. With improved access, the Klamath River soon gained a reputation as one of the finest sportfishing rivers on the West Coast. In addition to commercial fishing, Indians could now supplement their income or earn seasonal living as guides for sportfishermen.

A succession of poor salmon runs in the late 1920s led sportfishermen, through the Klamath River Anglers Association, to initiate state investigation of causes. Even though non-Indian commercial salmon trollers out of Eureka were fishing off the mouth of the Klamath, investigative committees appointed by the legislature in 1929 and 1932 determined that the decline was caused by Indian commercial river fishermen. They recommended closure of that fishery.

In 1933, after several years of controversy, the state of California

Space limitations dictated this chapter's focus on the currently controversial Yurok gillnet fishery of the lower Klamath River. It should not be inferred, however, that other Indian tribes of the area have not been involved as well. The Hupa tribe, particularly, has exerted tremendous effort over the years to define and protect Indian fishing rights.

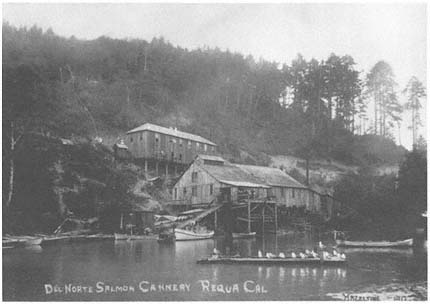

Last of its kind. This cannery at the mouth of the Klamath River, owned

and operated by non-Indians, employed Indian fishermen and plant work-

ers. It was closed by law in 1933.

(Peter Palmquist collection)

closed the commercial Klamath River fishery, which had been operating since 1876, and reinstated the Klamath as a navigable waterway. Opponents of the ban on commercial fishing felt that the closure would deprive many Indians of their livelihood. Proponents countered that the Indians could make more money as guides and boat pullers for tourists. The National Waltonian, August 1933, reported: "Sportsmen the country over will rejoice that the Klamath, famed for its piscatorial delights . . . has been saved for the public."

The Yurok fishermen took no such delight as the state of California, unchallenged by the federal government, banned both commercial sales and the use of gillnets by Indians for subsistence fishing in the lower Klamath. Indians lost more than their jobs—their most efficient method of fishing for food was made illegal. The propriety of state control of Indian fishing made manifest in this 1933 action was not legally addressed for several decades.

In 1969, the California Department of Fish and Game seized the gillnets of Raymond Mattz, a Yurok fisherman, and sought superior court permission to destroy or sell the "illegal" nets. Mattz claimed that state code prohibitions against net fishing did not apply on an Indian reservation. Although the state won in the lower court, Mattz appealed. The California Supreme Court upheld the lower court's judgment, but the U.S. Supreme Court, in Mattz v. Arnett (1973), reversed that judgment. In this unanimous decision, the Supreme Court held that the lower twenty miles of the Klamath River was still a reservation, despite its having been settled by non-Indians.

The case was then remanded to the trial court for a ruling on the applicability of state regulation to Indian fishing. After several appeals by the state, the U. S. Supreme Court, in Arnett v. Five Gill Nets (1976), upheld the rights of Indians to fish on the reservation free from state regulation.

The cases evolving from the confiscation of Mattz's nets created a jurisdictional void in the matter of Indian fishing regulations on the reservation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), as the federal trustee of Indian resources, moved to fill that void. In a key decision, the U.S. solicitor general concluded that "we know of [no authority] that would limit an Indian's on-reservation hunting or fishing to subsistence. The purpose of the reservation is not to restrict Indians to a subsistence economy, but to encourage them to use the assets at their disposal for their betterment. . . . Moreover, Indian fishing rights have on several occasions been interpreted . . . as extending to commercial fishing."

In 1977 the BIA published its first regulations to govern Indian fishing on the reservation. These allowed restricted commercial fishing in addition to subsistence fishing, but they were vague as to the amount of commercial harvest allowed and determination of which Indians were legally qualified to fish.

Improved regulations were published for the 1978 season, but the clamor resulting from the reinstatement of the Indian gillnet fishery continued to grow. A new sportfishing organization called the Klamath River Basin Task Force, as well as Del Norte County and the Hoopa Valley Business Council, initiated action to place a moratorium on commercial Indian gillnet fishing pending completion of an environmental impact statement.

A "strike force" of federal agents and park police, numbering up

to seventy-five men, in a hostile confrontation closed the Indian net fishery in midseason 1978. This "conservation moratorium," as it came to be known, lasted until 1987. Subsistence fishing was still permitted, and some violations of BIA regulations were reported during the period.

During the years between the Indian commercial fishery closure in 1933 and the mid-1970s, conservation had indeed become a key word in relation to the Klamath. Conservation measures were obviously needed. Intense logging, construction of major dams, and burgeoning offshore and inriver fishing took their toll. Two natural disasters, the 1964 flood and the 1977 drought, added to the destruction. The once fabled salmon runs of the Klamath River had become a national concern.

In 1976, the Pacific Fisheries Management Council (PFMC) was created by the federal Fishery Conservation and Management Act. Its primary role is to develop and monitor biological management plans for fish stocks from three miles to two hundred miles off the coast of Washington, Oregon, and California. This territory includes the Klamath Management Zone (KMZ), the commercial fishing area where Klamath River salmon are most vulnerable to harvest.

The initial PFMC management plan for the river called for a spawning escapement (the number of fish permitted to reach spawning grounds) of 115,000 fall chinook. From 1979 through 1982 the average actual number was 35,000 fish. Rather than close the ocean fishery, which would devastate local economies, the PFMC decided to institute a long-term correction, a phased twenty-year rebuilding schedule. The plan did not work: after only two years, spawning escapement had declined to 22,700 fish.

With the further decline of stocks because of the 1983 El Niño, PFMC felt its only option for 1985 under the rebuilding schedule was to prohibit ocean commercial harvest of salmon in the Klamath Management Zone. The impact of this action led to the formation of a "Klamath River Salmon Management Group" under the auspices of the PFMC. Representatives of lead agencies, with representatives of all affected fishing groups, met at the table—many tables!—to negotiate. By March 1986, they had worked out an agreement.

This innovative, nonadjudicated agreement included a new management scheme for the river. The new plan, called harvest rate

management, was based not on a fixed spawning escapement goal but on percentages of maturing adult fall chinooks that could be harvested by all fishermen—ocean or river—with a fixed percentage of the year's mature stock being left to spawn. Conservation responsibilities would be shared equally among user groups. Because its mathematical formulas promised to consider the needs of all groups, including the fish, it was guardedly acceptable to everyone involved. The resulting formal agreement was to be in effect for five years.

Under the new plan, the ocean fishermen were allowed a limited fishery in the KMZ in 1986, and in 1987 the Indian fishermen finally achieved an allocation of fish that was sufficient to lift the "conservation moratorium" placed on them in 1978. They were legally allowed to harvest fish commercially for the first time in fifty-four years (discounting the ill-fated effort during the late 1970).

In its second year, however, the new plan had to deal with problems not fully anticipated during negotiations: migrating salmon stocks from many separate river systems mix in the ocean and therefore contribute at different rates to the ocean harvest. Current technology dictates that the contribution rate of Klamath-origin salmon can only be estimated after the season's closing. That rate, a natural biological function, fluctuates according to location of catch effort and relative strength of stocks from other contributing rivers.

Before the season opens, biologists and regulatory agencies can only estimate what the abundance and contribution rate of the Klamath salmon will be, and from that estimate they shape a season to determine a harvest goal for Klamath fish. If their ocean population or contribution rate predictions are in error, serious harm to the fishing economy or the spawning escapement can result.

If the Klamath contribution rate is underestimated, ocean fishermen in the predetermined season may inadvertently take many more Klamath salmon than the allocation agreement permits. In such a situation, as occurred in 1987, with total abundance and contribution rates underestimated, both ocean and river fisheries are allocated fewer fish than accurate data would have allowed. The problem for Indian fishermen in such a case is that although the salmon catch of the river fishery can be accurately tallied—every fish entering the Klamath River is a "Klamath fish"—Indian harvest

is still restricted to the erroneous preseason predictions. While ocean trollers may harvest fish in other zones when their KMZ allocation is met, Indian river fishermen have no such compensating option.

Thus problems remain. While ocean regulations severely limit fishing within the KMZ, areas north and south of the zone have relatively liberal seasons. Fishermen in these areas of mixed-stock fishing take almost all of the Klamath salmon allowed for ocean harvest under allocation agreements, leaving few to allocate to their fellow fishermen inside the zone.

No one is happy. Ocean fishermen are distressed with limited seasons, and agency biologists are frustrated with the demand, both biological and social, for management numbers they are unable to supply. Nor are the Indian fishermen happy. Most perceive any increase in the allowable ocean harvest, while they in the river fishery must conform with the numbers of the agreement, as yet another breach of trust.

Negotiations continue on overall harvest rates and allocation. Ocean trollers want more Klamath fish to harvest in the KMZ. Their counterparts to the north and south are unwilling to reduce harvest of other stocks to protect Klamath fish mixed with them. The Indians, with their revitalized commercial fishery economy, will certainly fight to keep their allocation. And, above all, a spawning escapement must be developed and maintained that will allow for perpetual renewal of stocks.

While conservation efforts, through negotiation and regulation, are working to a certain extent, as evidenced by increases in spawner escapement, companion efforts in the restoration of fishery habitat in the Klamath/Trinity basin must also be addressed. Indian people residing on the river from its headwaters to the ocean have long decried the destruction of the spawning and rearing habitat of the river. Impacts of the modern world are many: logging that denudes hillsides and dumps silt onto spawning beds; dams that reduce the river's flow; streambanks stripped of trees, which causes overheated water; unscreened diversions for agricultural irrigation that bleed off juvenile fish; road-crossing culverts that block passage to spawning beds; months of streams filled in with deposited gravel, blocking fish passage. All these conditions contribute heavily to the decline of fish production.

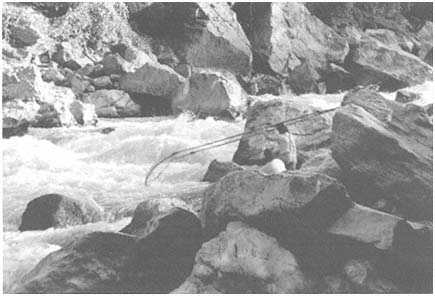

Young fishermen, ageless site. Karok tribesmen hoopnetting for salmon at

the Klamath River's Ishi Pishi falls in 1989. This fishing site has been used

by Native Americans since ancient times.

(Andy Kier)

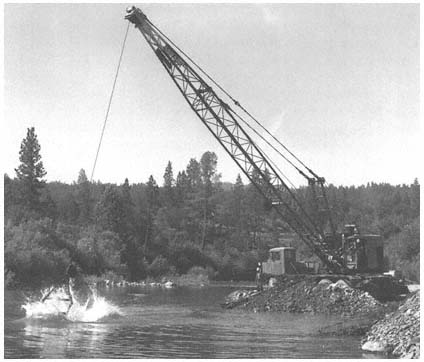

Life cycle nearly complete. These salmon are migrating to spawning areas

in the Trinity River. Most salmon return to their native waters to spawn.

(Bureau of Reclamation)

Cool water needed. Dredging, equipment removing gravel to create cold

water pools for protection of salmon and steelhead on the Trinity River.

(Bureau of Reclamation)

In 1982, the Bureau of Indian Affairs responded to concerns about declining salmon runs by commissioning the Klamath River Basin Fisheries Resource Plan. The plan provided the needed insight and direction for congressional action to restore Klamath River fishery resources. Legislation enacted in October 1986 provides that $21 million will be appropriated by the Department of Interior from October 1, 1986, through September 30, 2006. A matching $21 million is to be provided by nonfederal sources. Under the act, a fourteen-member Klamath River Basin Fisheries Task Force has been created that embodies all pertinent management agencies, fishing groups, and counties of the basin.

Tribal management of tribal resources is the goal of Indian people nationwide, and the U.S. government, through the Bureau of

Indian Affairs, promotes this goal of Indian self-determination. The Yurok people, as they now move toward the twenty-first century, have managed to hang on to their fishing rights and have reestablished the right to sell a portion of their harvest.

On October 31, 1988, Congress created a separate Yurok Reservation and actuated formal organization of the Yurok tribe. The right to restore and manage the fishery resources of the reservation, both "in the gravel" and at the policy level, has always been a high priority of Indian fishermen. This most recent action has the potential for future resolution of the confusing jurisdictional issues that have been inherited. The stage is set for great strides in Indian self-determination, as well as restoration of the Klamath basin's fishery resources.