Preface

It was one evening at the Lincoln Center in New York. Pavarotti's voice filled the auditorium with 'Mama', one of those arias he sings so well, and the audience, in appreciation, gave him a thunderous ovation. As he came back for yet another bow, my mind suddenly flashed back, and that other world to which I once belonged came into sharp focus – the bends of the Nqabarha River, the meadows, the animals, the simple country folk, the school kids pouring out of the school-gate at the end of the day. I saw them all, as I had seen them so many times in that far-off time and place. I sat down, cupped my head in my hands and bowed my head, softly saying to myself: 'How strange! Little do all these people know that while I am part of them at this particular moment, I am part of another world of which they know so little. I come from Gqubeni along the bends of the Nqabarha River. That's where my roots are. That's me!'

Some years ago, my daughter-in-law Casey once asked me: 'P, how did you and Joe meet? Just tell us.'

Laughing, I dismissed her question with: 'You know, where I come from, that is one subject parents do not discuss with their children. Maybe one day I'll tell you how it happened.' We both laughed and left it at that.

After that night at the Lincoln Center, it occurred to me that, perhaps, my other world was part of me in a way that not even my children knew, let alone the friends around me that night. How could my children, born and raised in the city, know anything of this other world? What they knew of this world were snatches gleaned from me and their dad and all those other visitors from the country with whom they came into contact when

they were growing up.

Even to answer Casey's question, I had to go back to this other world. It was the only way she would understand why and how I ended up marrying Joe. So I started jotting down notes, recounting my experiences that span three continents, experiences that have shaped and moulded me into the person that I am.

I wanted to leave a record of my life for my children and my grandchildren and all those other friends I have met in my sojourn through life, for them to know and understand that it was because of these far-off roots that I am the person I am. It was to say to them: 'Ndivel' eGqubeni, nindibona nje!' [You see me here! I come from Gqubeni!] Yes, this is my story.

Like Trotsky, I did not leave home with the proverbial one-and-six in my pocket. I come from a family of the landed gentry in Transkei, the kulaks of that area. I could, like many others in my class, have chosen the path of comfort and safety, for even in apartheid South Africa, there is still that path for those who will collaborate. But I chose the path of struggle and uncertainty.

I trace the foundations of this attitude to my upbringing in a home where the less fortunate and destitute always came and found help and succour. From a very early age, I was made aware of the needs and problems of others and I saw all these people treated with dignity and humanity. This had a tremendous impact on me as a child, even though there were never any lectures on it. And yet I am still very class conscious and, like most people from my class, very arrogant. My arrogance, however, has always been tempered with concern, sympathy and caring for the less fortunate. From this class position, I knew quite early that I was as good as the best, black and white.

This book is not a political thesis. But I have used the story of my life as a peg on which to hang life and events in South Africa and North America as I experienced them. We have here a huge canvas, depicting the mosaic that is South Africa, with all its colours, strong and subdued, its lines long and short, and the dots, large and small. In social life, it is people who make up that mosaic; it is they who make things happen. Their actions and interactions determine the course of events. At the very centre of all this are human relations, and to understand those human relations, we must meet real people, hear them speak, how they speak, and then we shall know why they speak the way they do. A summary of events does not and

cannot give the whole picture; the nuances are lost in a synopsis. The whole mosaic has to be seen – lines, dots, colours and all – in its totality, to be appreciated.

In drawing this mosaic we have gone back in time and history; given a lot of background and sometimes in detail, for to understand the present, we must know the past; even to predict the future accurately, we have to know that past, as it was in the past that the seeds of the future were sown. For how can one explain and understand Granny Matthews, wife of the late Professor Z. K. Matthews, so English and yet so African? Of the African women I know, there are none as African and aware of their great African heritage as she is. And yet, on the surface, she is so English. Or how can one understand my husband A.C., peasant in outlook, one who remained suspicious of city ways to the end of his life, and yet, as a Classical and European scholar of literature, history and music, one who could field with the best? One needs to know the roots from which such people have sprung.

Here is also a slice of the mosaic that is America, a country not unlike South Africa in many ways. Both are young and vigorous, the meeting-place of Africa and Europe. Nature has graciously smiled on both and endowed them with riches under and above the ground and with a beauty unsurpassed. Their people are warm, kind, generous and with a concern for others. Bigotry and racism are a curse on both, for in both colour is king. Arrogance of power is a plague in both, power so ruthless and manipulative that it allows nothing to stand in its way. Yes, so much alike and yet so different! There is a promise and a future in America, for the bedrock of her foundation is a constitution that guarantees liberty, equality, freedom and the pursuit of happiness to all her people. For South Africa there is now a promise, some hope. But the future is still blurred.

There had been stirrings in me even before I left the University of Fort Hare. The blatant racism at Healdtown where I went to school had opened my eyes. This was not so much directed towards us, the students. After all, the white establishment there was a little distant from us, and the three whites on the High School staff could not be accused of being racists. It was the attitude of the white colony towards the African staff that disgusted me. I resented this with all my soul and could not wait to get out of that place. I strongly suspected that the interests of this establishment were inimical to mine. So by the time I got to Fort Hare, all establishments were suspect.

It was in Kroonstad where I came to teach that my anger was aroused. It was concern for my students whose hopes and ambitions seemed to end in a cul-de-sac that made me ask 'why' and seek answers to the problems of poverty that thwarted the ambitions of such good students. I was not to find answers until I got to Cape Town. Here I learnt that, though I seemed free, there could be no freedom where others were not free and that in fact, nobody in South Africa, or any other country, was free while others were not. I learnt also that it was not the ill-will of any individual white person or group of them, but a system of exploitation that benefited only a few and saw the rest of mankind as units of labour that could be exploited for the benefit of those few who held the economic power. This was what was responsible for the miserable plight of so many people in my country and in other parts of the world. It was brought home to me in Cape Town that not until this system of exploitation of Man by Man had been smashed and disbanded could there be freedom in the world. And it was people who, by taking their destiny in their hands, could change things, turn them around and create for themselves a new world, a humane world of free, liberated people. Having understood this, I could not leave it to others to do. I had to be part of it.

My stepmother, Edwina, with baby Somikazi

on the outside veranda at home

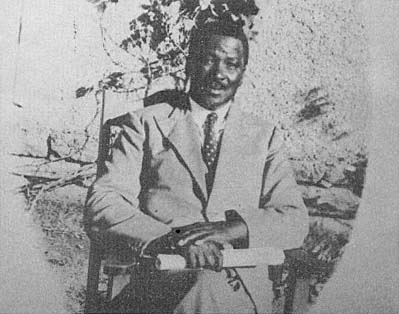

Tata, my father, as I knew him in my youth. He was 59 when this photograph

was taken.

Fort Hare Rag, 1935: Phyllis as Harlem girl, Vin

Kraai as golfer

My wedding day, eGqubeni, 2 January 1940.

Phyllis and baby Nandi (15 months), Kroonstad

Sister Nontsikelelo, A.C.'s sister, with

baby Pallo (3 weeks), Kroonstad

A.C. Jordan, Cape Town, early 1960s

Nandi on her way home from the Little

Theatre, Cape Town.

Ninzi, New York, 1967

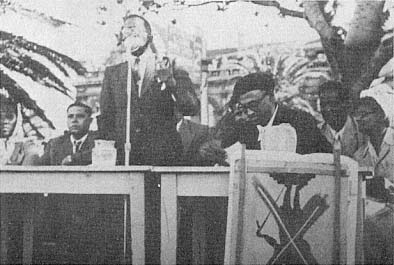

Meeting held on the Grand Parade, Cape Town, 30 March 1952, during the

campaign against the Van Riebeeck Celebrations. On the platform from left:

Phyllis Jordan, Willem van Schoor, S.A. Jayiya, Goolam Gool, Dan

Neethling, Jane Gool.

Lindi (7 years) and Pallo (10) with Bojie, A.C.'s nephew, Cape Town

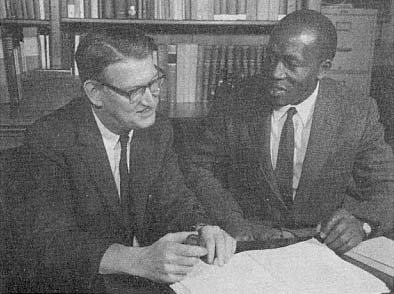

A.C. with Dr Claggert, Director of Center for Research, University of Wisconsin,

Madison, 1962.

Z. Pallo Jordan, London

A.C. and Phyllis photographed for the Capitol times of Madison on the day

the news broke of Pallo's endorsement out of the USA, March 1967.

A SALUTE TO

Tata, my Grand Old Man, friend and first teacher

A.C., my husband, comrade and colleague

Granny, Somblophe and Ntangashe, my wonderful sisters who

protected me throughout my growing years

Nqokothwana (Mzukie), the brother for whose coming I prayed

and Nandi, Ninzi, Pallo and Lindi, my children and

source of my inspiration

AND A LEGACY TO

my grandchildren, Thuli Ofuma, Samantha Lee and

Nandipha Esher