PART II

METAPHORIC REFLECTIONS OF THE COSMIC ORDER

4

The Shamanistic Inner Vision

The mask Moctezuma presented to Cortés had a long history and a number of levels of symbolic meaning. In fact, the beginning of its history and the source of its meanings must be sought in a time long before any actual masks appear in the archaeological record as the roots of the ritual and symbolic use of masks characteristic of Mesoamerican religion are deep in the shamanistic base from which that religion grew. Throughout the long history of its development, it continually drew sustenance from the basic conceptions brought across the Bering Straits land bridge as early as 40,000 years ago by the first discoverers, explorers, and settlers of the New World and bequeathed by those first Americans to all the generations who were to follow them in the development of what was to become the indigenous thought of the high cultures of Mesoamerica. All the subtlety, intricacy, complexity, and beauty of the thought and ritual of the highly developed religious institutions of Mesoamerica at the time of that second contact with the Old World, known as the Conquest, can be seen as developments from the shamanic base, developments from that original archaic religious system built on the individual shaman's ability to break through the normally impenetrable barriers that separate the planes of matter and spirit. His was an ecstatic personal experience with practical uses for his people, the hunting and gathering, nomadic peoples of the Early Paleolithic and later times. As magician, diviner, or curer, he was uniquely capable of bridging the gap between the mundane lives of the people of his community and the mysteries of the invisible world which could give those lives purpose, direction, and meaning and through which the ailments and problems of the individuals and the community could be dealt with. Of course, the highly developed religions of the later civilizations of Mesoamerica no longer depended upon the central figure of the shaman and the trance through which he was able to enter the world of the spirit, but the outlines of that shadowy figure can still be seen in the basic assumptions and many of the practices of the religions he founded.

The significance of shamanism to Mesoamerican spiritual thought has been recognized both by those who study Mesoamerica and those who study mythology and religion generally. Campbell, for example, among the latter group, has pointed out that "in any broad review of the entire range of transformations of the life-structuring mythologies of the Native Americas, one outstanding feature becomes immediately apparent: the force, throughout, of shamanic influences."[1] In this, he concurs with Eliade who, in his definitive study of shamanism, shows that "a certain form of shamanism spread through the two American continents with the first waves of immigrants."[2] Among Mesoamericanists, Furst, who claims that the shamanic world view forms the basis of "mankind's oldest religion, the ultimate foundation from which arose the religions of the world,"[3] notes that even the relatively late Aztec religion, which was certainly not dominated by the individual shaman and his trance, retained "powerful shamanistic elements"[4] that were derived from the fundamental shamanic assumptions underlying Mesoamerican religious thought and practice. A brief treatment of those assumptions will illuminate their shamanic origin and, interestingly, suggest an important reason for the widespread mask use we have traced in Mesoamerican religious symbolism and ritual.

Perhaps the most fundamental assumption shared by shamanism and Mesoamerican religion holds that all phenomena in the world of nature are animated by a spiritual essence, the common possession of which renders insignificant our usual

distinctions between man and animal and even the organic and the inorganic. In the shamanic world, everything is alive and all life is part of one mysterious unity by virtue of its derivation from the spiritual source of life—the life-force. Thus, each living being is in this sense merely a momentary manifestation of that eternal force, a mask, as it were, both covering and revealing the mysterious force of life itself. Furthermore, the commonality of the life-force makes possible within the shamanic context the primordial capability of magical transformation; man and animal can assume each other's outer form to become the alter ego, an ability central to the pan-Mesoamerican concept of the nagual , which is discussed below. Through this form of transformation, the shaman can explore the myriad dimensions of the material and psychological worlds; and through the concomitant liberation from the limitations of his own body, he can take the first step toward the exploration of the worlds of the spirit, the proper domain of his own spiritual essence. The ritual use of mask and costume clearly derives, at least in part, from that concept of magical transformation: through the mask, the ritual performer changes his physical form to enter the world of the spirit in a way analogous to the shaman's magical transformation.

A second assumption of shamanism that underlies Mesoamerican religion follows directly from this first one. In the shamanic universe, the soul, or individual spiritual essence, is separable from the body in certain states or under certain conditions; the spirit can become autonomous and function free of the body. Man is thus not necessarily limited to or by his physical existence; he is capable of moving equally well in each of the two equivalent worlds of which he is a part—the natural and the spiritual. This equivalence of the worlds of matter and spirit makes the common distinctions between dream and experience, this world and the afterworld, the sacred and the profane, as insignificant as those between man and animal because the shaman demonstrates that the only true reality is spirit, albeit spirit that may be temporarily garbed in the material trappings of the world of nature. Just as the spirit of the shaman can transform itself into other forms of natural life, so it can leave the physical body entirely and "travel" unfettered in the spiritual realm. It is there, of course, that the shaman finds what is needed to cure the ailments and solve the problems of his people, one of his primary functions in a world that believed the cause of everything in nature was to be found in the world of the spirit. Thus, the physical being of the shaman, and of living things generally, was a "mask" placed on the spiritual essence, a "mask" that could be removed and left behind in the shaman's ecstatic journeys to the world of the spirit. The actual masks and costumes worn by shamans suggested symbolically the separability of the worlds of matter and spirit, and precisely this symbolic meaning of mask and costume was to remain constant throughout the development of Mesoamerican spirituality.

This belief in the separability of matter and spirit concurs with a third basic assumption of shamanism and of Mesoamerican religion—that the universe is essentially magical rather than bound by what we would call the laws of cause and effect as they operate in nature. Since material realities were the results of spiritual causes, to change material reality, the spiritual causes had to be found and addressed through ritual and/or shamanic visionary activity. The magical universe consisted of two levels of spiritual reality, one above and one below the earthly plane, a shamanic conception that directly prefigures the structure of the cosmos as it was seen at every stage of the development of Mesoamerican spiritual thought. The three levels are connected by a central axis, often represented by a world tree, "soul ladder," or stairway that links the planes of spirit and matter and provides the pathway for the shaman's spiritual journeys. Again, shamanism posits a universe in which matter and spirit are separate yet joined, and that union both makes possible and is symbolized by the spiritual travel of the shaman when he takes off the "mask" of his physical being.

These assumptions are the core of shamanism. They suggest the fundamental spirituality of man and provide a conceptual base for the belief that through appropriate rituals performed by one who, by heredity, divine election, or the manifestation of a proclivity for the sacred, has acquired the ability to shed his physical being to become "pure" spirit, all boundaries can be crossed so that the zones of profane space and time can be transcended and the essential order of the cosmos revealed. The shaman is thus the mediator between the visible and the unseen worlds, the point of contact of natural and supernatural forces. Significant among the supernatural forces are the figures of his ancestors, the clear embodiment of death and the life after death. In thus linking the natural with the supernatural, the material with the immaterial, and life with death, the shaman establishes an inner metaphysical vision of the primordial wholeness of cosmic reality. He, himself, has left his body through a symbolic death, traversed the realms of both life and death, and returned to tell the tale. As he returns from his visionary experience, he again puts on the "mask" of the material world so as to communicate that experience and share his vision of the world of the spirit with his community.

Black Elk, the visionary Native American of comparatively recent times, beautifully suggests the essence of this shamanic vision characteristic of the indigenous cultures of the Americas.

I was standing on the highest mountain of them all, and round about beneath me was the

whole hoop of the world. And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell and I understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must live together like one being. And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.[5]

That "sacred manner" of seeing which reveals the mysterious unity, the "one circle," at the heart of things is the ecstatic vision of the shaman, and it is as central to Mesoamerican thought and ritual throughout its development as it was to Black Elk's somewhat different vision of reality.[6] From that very sense of the spiritual unity of the cosmos, the cultures of Mesoamerica developed a religion that saw man's existence in essentially spiritual terms and that concentrated its ritual actions on symbolizing and breaking through the boundaries between the planes of matter and spirit through such means as the attainment of trancelike states induced by ritual privation, blood sacrifice, or the ingestion of hallucinogens; ritual human and animal sacrifice; and masked dance. As we have shown, even the sacred spaces in which these ritual activities took place were themselves symbolically "marked" by the use of masks to suggest the ultimately shamanistic idea of the separability of the worlds of spirit and matter. Underlying all these fundamental ritual practices we can see the vision so well described by Black Elk.

But it is not only in its shamanistic assumptions that we can find evidence of the shamanic base of Mesoamerican religion. Numerous clearly shamanic practices have been and continue to be integral parts of Mesoamerican religious activity. They can be seen in connection with funerary ritual, symbolic animal-human transformation, the attainment of trance states through the use of hallucinogens, and in the healing practices still associated with Mesoamerican spirituality. Evidence of all these practices can be found very early, but the earliest is, of course, fragmentary as a result of the destructiveness of man and nature through the course of the centuries and of the fact that archaeological research on Preceramic Mesoamerica is in its infancy. Significantly, however, MacNeish, one of the pioneers in that research, has found archaeological evidence to confirm that as early as the El Riego phase in the Tehuacán valley (ca. 6000 B.C.) there was "a complex burial ceremonialism that implied strong shamanistic leadership."[7] Since, as we have seen, the shaman is intimately involved with death in his movement between this world and the afterworld and since burials often preserve archaeological material, it is not surprising that the early evidence of shamanic practices involves mortuary ceremonialism, the ritual involved with man's ultimate movement between the worlds of matter and spirit. That these very early shamanic burial customs persisted in central Mexico is indicated by the association between funerary ritual and male figurines dressed in shaggy costumes suggestive of the paraphernalia of the shaman as jaguar[8] found at Tlatilco as early as 1500 B.C. and as late as A.D. 750 on a grander scale at Teotihuacán. Soustelle discusses the examples from Tlatilco and concludes that

certain individuals wore garments, ornaments, masks that set them apart; no doubt these individuals were "shamans," awesome figures, respected and feared, intermediaries between the human world and the supernatural forces whose powers lay in a domain somewhere between magic and religion. Such magician-priests still exist today in Indian communities.[9]

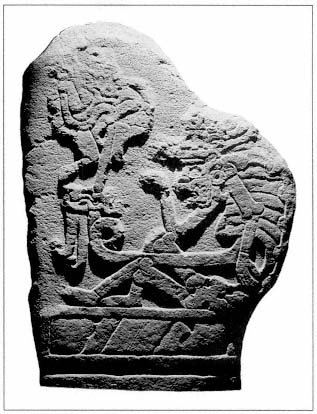

Covarrubias also sees a funerary jaguar-shaman relationship in figurines from a Tlatilco burial. Each of the "shamans" is accompanied by a dwarf and each is wearing a small mask, some of the masks jaguarlike and others designed so that half portrays a contorted face with a hanging tongue and half is a human skull (pl. 52), together suggesting the duality of life and death,[10] one of the fundamental assumptions of shamanism. That this symbol of the equivalence of life and death, matter and spirit is found in the shape of a ritual mask worn by a shamanic ritual figure further strengthens the contention that the cultures of Mesoamerica from very early times consciously used the mask as a primary symbol for the idea that the material and spiritual worlds coexist in such a way that the material world acts as a covering for the world of the spirit, a covering that can be penetrated through the symbolic death of the shaman's ecstatic trance. We can also see in these early symbols and ceremonies associated with death the roots of the complex system of communicating with the world of the spirit through human and animal sacrifice which was characteristic of the cultures of Mesoamerica. That system of communication, already suggested by the sacrificial victims in the El Riego phase of the Tehuacán valley, was perhaps a logical development from the deathlike trance of the shaman which enabled him to enter the world of the spirit. In both cases, a form of death was seen as the necessary prerequisite for the spiritual journey.

Evidence of this transformation, through death, from matter to spirit is complemented in the archaeological record of early Mesoamerica by widespread indications of another sort of transformation. As we have demonstrated in the section "Merging with the Ritual Mask," such masks from the earliest times give evidence of the merging of human and animal features in the process of the

transformation of matter into spirit through art and ritual. Numerous figurines from such Preclassic sites in the Valley of Mexico as Tlatilco, Tlapacoya, and Las Bocas; a good deal of Olmec sculpture both from the heartland on the Gulf coast and other sites ranging from Chiapas to Puebla; and a number of examples of the early sculptural art of Monte Albán, all roughly contemporary, depict or suggest such transformations of man into animal, often a jaguar or bird. Both of these creatures are associated with the shaman and both, as we have seen, are potent factors in Mesoamerican spiritual symbolism. Such a transformation, of course, suggests the shaman's ability to transcend the material world and to transform himself into other natural forms. This assumption of the outer form of an animal alter ego was no doubt "the most striking manifestation of his power"[11] and was an integral part of his ability to enter the world of the spirit. Thus, the early masked rituals recorded by these ceramic and stone figures and those that followed them in the later cultures of Mesoamerica must often have effected a symbolic transformation of the essentially shamanic figure into his animal counterpart in the process of penetrating spiritual reality.

The jaguar, always important symbolically in Mesoamerica as we have seen in the context of rain, fertility, and rulership, is a key figure in these symbolic transformations, and linguistic studies showing that in some areas of the New World the words for jaguar and shaman are the same[12] offer further evidence of shamanic transformation. And, significantly, the Aztec name for the shamanic sorcerer-priest-curer, nahualli, was the same as the word that denoted the animal alter ego into which the sorcerer could transform himself. These two linguistic connections between priest and animal underscore Furst's claim that the jaguar's importance throughout Mesoamerican symbolism is connected with the fact that it is interchangeable with, or a kind of alter ego of, men who possess supernatural powers.[13] According to Eliade, the "mystical journeys [of the shaman] were undertaken by superhuman means and in regions inaccessible to mankind";[14] thus, the magical transformation of the shaman into a bird or an animal that could move with superhuman speed would symbolically supply the powers needed to make the journey into that other realm of being.

Recent research indicates that both of these forms of transformation—from matter to spirit through a symbolic death and from man to animal—were often accomplished through the ingestion of psychotropic substances by which the shaman attained the necessary mystical, ecstatic state that would enable him to transcend human time and space and gain insight into the divine order. That research provides evidence of the use of hallucinogens early in the development of Mesoamerican religion. The abundant remains of Bufo marinus at San Lorenzo, for example, suggest that the Olmecs sought the hallucinogenic effects of eating these toads.[15] Coe and other students of the Classic period Maya have found extensive evidence on painted ceramics of the practice of ritual hallucinogenic enemas, a practice that seems to have roots in the Preclassic.[16] Furthermore, "the presence of mushroom stones and associated manos and metates in Middle and Late Preclassic caches and tombs indicates the existence of a widespread mushroom cult similar in concept, but not necessarily in performance, to that known [today] among the Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and Mixes of Oaxaca."[17]

This fragmentary evidence of the shamanic use of hallucinogens in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica takes on its proper significance when we examine the use of hallucinogens among the Aztecs. Because Aztec thought is far better documented than that of any other pre-Columbian civilization, the use of hallucinogens, like many other areas of spiritual thought and practice, can be better understood within Aztec culture than in the cultures of Classic and Preclassic Mesoamerica. The evidence of their extensive ritual use of hallucinogens to command visions of destiny and to experience the order to be found in the unseen world no doubt indicates that we would find the use of hallucinogens equally pervasive in earlier cultures were similarly extensive evidence available. The Aztecs considered psychotropic plants sacred and magical, serving shamans, and even ordinary people, as a bridge to the world beyond.[18] Providing the ability to enable man to communicate with the gods and thereby to increase his power of inner sight, such hallucinogens were important enough to be associated with the gods. Xochipilli, for example, was not only the god of flowers and spring, dance and rapture but patron deity of sacred hallucinogenic plants and the "flowery dream" they induced. He is often portrayed with "stylized depictions of the hallucinogenic mushroom" and "near realistic representations of Rivea corymbosa ," the morning glory, called ololiuhqui by the Aztecs, whose seeds are hallucinogenic, as well as tobacco and other hallucinogens,[19] and in one of his most powerful representations he is depicted masked.

As such depictions indicate, many plants by which the shaman could induce his visions were included in the psychoactive pharmacopoeia discovered by the Spanish conquerors. In addition to sacred mushrooms, the morning glory, and a very potent species of tobacco called piciétl , there was peyote, a hallucinogen still widely used by the indigenous peoples of northern Mexico and the southwestern United States in ritual activity. Similarly, Durán tells of the Aztec use of teotlacualli, a divine brew made up of tobacco, crushed scorpions, live spiders, and centipedes which priests smeared on themselves and drank "to see visions."

He reports that "men smeared with this pitch became wizards or demons, capable of seeing and speaking to the devil himself."[20] What seemed devilish to Durán, of course, was the plane of spiritual reality entered through the ecstatic trance of the shaman, the plane on which he could find spiritual knowledge.

The evidence of shamanic practices within Mesoamerican religion, then, clearly shows a shamanistic emphasis on transformation often accomplished through a hallucinogenic alteration of the mental state of the religious practitioner. As is the case with the traditional shaman of Siberia, in Mesoamerica these transformations often served the purpose of healing the physical and psychic ills of members of the community. A wealth of evidence, much too vast to cite here, points to this link between shamanism and Mesoamerican healing practices which existed from the earliest times and continues to the present day. Some representative examples, however, will suggest the nature of the connection. The Yucatec Maya Ritual of the Bacabs, which dates from pre-Columbian times, contains long incantations to be used by the healer in ridding the community of disease. Through this ritual, he could send the diseases inflicted by the underworld rulers on the race of men back through the entrance to a cave and thence to the underworld and the realm of death from which they came. And Landa, writing about the duties of Maya priests at the time of the Conquest, reports that they used knowledge drawn from the world of the spirit through shamanic means in the process of healing: "The chilánes were charged with giving to all those in the locality the oracles of the demon. . . . The sorcerers and physicians cured by means of bleeding at the part afflicted, casting lots for divination in their work, and other matters."[21] Vogt's research among the contemporary Maya in Zinacantan has uncovered ample evidence of the continuation into the present time of similar shamanic healing rituals exemplified by what he calls "rituals of affliction."

Many of these ceremonies are focused upon an individual "patient" regarded as "ill." But the illness is rarely defined as a physiological malfunctioning per se; rather, the physiological symptoms are viewed as surface manifestations of a deeper etiology; for example, "the ancestral gods have knocked out part of his soul because he was fighting with his relatives."[22]

Through divination, the Zinacantecan shaman determines the state of the patient's animal alter ego in the realm of the spirit and proceeds ritually to restore the animal to its proper position, thus curing the patient. In much the same way as in pre-Columbian times, "the patient's relationship with his social world is reordered and restored to equilibrium by the procedures of the ritual."[23]

These shamanic healing practices were not limited to Maya Mesoamerica. In the Valley of Mexico, the Aztecs, too, placed great faith in the healing power of the sorcerer-priests who coexisted with the priests of the institutional religion of the temples. Generally referred to as shamans, these sorcerer-priests were the guardians of the physical and, to some extent, the psychic equilibrium of the community. According to Caso, each human imperfection was "transmuted [by the Aztecs] into a god capable of overcoming it."[24] In this way, the imperfections and ailments became spiritually accessible to the shaman. Whether through animal transformation, by the imitation of animal voices, or by chanting incantations using the nahualtlatolli, or "disguised words," the shaman could enter the place and "time where everything was possible to elicit the supernatural power of the gods and their primordial handiwork in the restoration of the patients' health and equilibrium."[25] This magical approach to healing is also evident in the belief that particular words could be pronounced by the shaman to control nature and cure the destructive imperfections plaguing a person or the whole community. These few representative indications of shamanic healing practices could be multiplied indefinitely, but they must serve here to indicate the widespread and long-lasting influence of shamanism on healing among the indigenous cultures of Mesoamerica.

Thus, the shamanic origin of Mesoamerican religion seems to be clearly indicated by many practices that derive from the fundamental assumptions of shamanism. More important than any of these particular forms of religious activity, however, is the fact that the way of seeing reality characteristic of Mesoamerican spirituality is the way of the shaman. In this connection, it is fascinating to note what seem to be indications of the shamanic origins of the gods of Mesoamerica, the metaphoric figures which inhabit and represent the spiritual realm, the true home of the spirit that animates man. In typical shamanic fashion, they are ranged on a number of levels of spiritual reality above and below the plane of earthly existence. Chief among the gods represented at the time of the Conquest in the Valley of Mexico, as we will show below, was Tezcatlipoca, whose cult at Texcoco "still retained echoes of an archaic, shamanic origin among the tribesmen of the north, embodied principally in a revered obsidian mirror, a magical artifact shamanistically used for divinatory scrying."[26] Nicholson sees in that mirror "Tezcatlipoca's ultimate origins," the source of "his role as archsorcerer, associated with darkness, the night, and the jaguar, the were-animal par excellence of the Mesoamerican sorcerer-transformer."[27] Seeing the mirror as central to Tezcatlipoca's identity and role suggests a relationship between that god and the iron-ore mirrors that dot the archaeo-

logical record as far back as the Olmecs.[28] Perhaps even that early, they were associated with a prototypical Tezcatlipoca and with the shamanic ritual connected with him. Nicholson suggests a similar background for Ehécatl-Quetzalcóatl, Tezcatlipoca's polar opposite and complement, who "appears to have functioned both as a patron of the regular priesthood and of those practitioners of various techniques which most anthropologists would classify as shamans."[29] These two important examples of the gods' origins in the shamanic past of Mesoamerican religion and myth suggest clearly the strength of the shaman's influence throughout the religion's long course of development and also provide a fascinating connection with the use of the mask as a metaphor within the Mesoamerican religious symbol system. Since the gods' origins were in the shamanic beginnings of Mesoamerican religion, their consistent depiction as masked human beings can be seen even more clearly as a metaphoric reference to their function in uniting the worlds of spirit and matter and in defining the spirit world through the symbolic features of the mask.

This influence also explains the pervasive symbolic and ritual use of masks in that religious development as the use of masks is a significant part of both the symbolism and ritual of shamanism. As Eliade points out, the mask of the shaman, the specialist of the sacred who has learned to move between the worlds of nature and spirit, "manifestly announces the incarnation of a mythical personage (ancestor, mythical animal, god). For its part, the costume transubstantiates the shaman, it transforms him, before all eyes, into a superhuman being."[30] In ritual, the mask provides the shaman with one of the important means of accomplishing his essential function—the movement into the realm of the spirit. In a similar way, shamanic songs or incantations suggested that same transformation, as did even "disguised words" or the imitation of animal voices, which served as a "sign that the shaman can move freely through the three cosmic zones: underworld, earth, sky."[31] The new, musiclike language of the liberated spirit of the shaman signified his movement away from the mundane world in his quest for sacred knowledge. These songs or chants are "a discipline of the interface between waking consciousness and night," the meeting point of the metaphoric equivalents of the worlds of nature and the spirit. Thus, the equation of masks with song by Levi-Strauss, though not in connection with shamanism, suggests again the central symbolic function of the mask within the shamanic context. He explains that

within culture, singing or chanting differs from the spoken language as culture differs from nature; whether sung or not, the sacred discourse of myth stands in the same contrast to profane discourse. Again, singing and musical instruments are often compared to masks; they are the acoustic equivalents of what actual masks represent on the plastic level .[32]

Masks, then, are the visual equivalent of the song or chant of the shaman, and both mask and song are symbolic of the sacred discourse of myth created by the mind. All three—masks, song, and myth—are products of culture operating at its most profound level in a search for order in the invisible or spiritual world. Eliade's contention that the mask makes it possible for the shaman to transcend this life by enabling him "to become what he displays" and to exist as "the mythical ancestor portrayed by his mask"[33] suggests precisely the necessary immersion in the sacred order of the world of the spirit. Through the mask and the song, the shaman is transformed into something other , and with the vision of an animal, ancestor, or god symbolically acquired through this transformation, he is able to see into the mysteries of the spiritual realm. "He in a manner reestablishes the situation that existed in illo tempore , in mythical times, when the divorce between man and the animal world had not yet occurred,"[34] when the primordial order had not yet been hidden from man's view. Now outside of space and time, "he mystically unites himself with a sacred order of being, beyond the dimension of this or that person in this or that particular body."[35] He is, in effect, reborn with the divine ability to see, behind the mask that both covers and reveals the essence of the cosmos, the divine order that alone can resolve the seeming chaos of the world of man. Thus, the mask is surely a clear reflection of and the perfect metaphor for this shamanic world view, and Mesoamerican spirituality reveals its great debt to shamanism in its pervasive symbolic and ritual use of the mask.

Wherever we look in our study of Mesoamerican spirituality, we come face to face with its shamanic ancestor. Whether we are considering the use of divination to understand the "augural significance of dreams"[36] or noting that a burial ceremony provides a way of establishing contact with the ancestors who can show the way to the world of the spirit that they now inhabit; whether we find evidence of transformation into animals suggesting the transformative vision that provides the powers that are needed for the mystical journey or study healing accomplished by curers able to divine the cause of disease and find its cure in the spiritual realm; whether we find visionaries under the influence of hallucinogens predicting future events and establishing "auspicious times for the holy rites,"[37] we are consistently seeing practices whose roots are deep in the shamanic base of Mesoamerican religion. They all derive from the fundamental shamanic conception of an underlying cosmic order, an order of the spirit—the "sacred hoop" described by Black Elk.

It was precisely this shamanistic transcendence

of all mundane distinctions between the sacred and the profane, inner and outer, man and animal, dream and reality, that enabled Mesoamerican man to feel at one with a universe that included all the anxieties of life and death in its mysterious complexity and to be initiated "by shamans into a system of philosophical, spiritual, and sociological symbols that institutes a moral order by resolving ontological paradoxes and dissolving existential barriers, thus eliminating the most painful and unpleasant aspects of human life"[38] by putting them in their "proper" perspective. Perhaps the comfort of the shamanic world view through which "the Indians approached the phenomena of nature with a sense of participation"[39] gave Mesoamerican man his first impulse to search in all the other areas of the cosmos for similar manifestations of the same phenomenon. And in addition to providing the impulse, it seems clear that shamanism also provided the conceptual framework for the magnificent cosmological structure that resulted from Mesoamerican man's spiritual search. The shamanic vision can be found in every aspect of Mesoamerican spiritual thought making up that structure: in the underlying temporal order of the universe demonstrated in both the solar cycles and the cycles of generation from birth to death to regeneration; in the spatial order derived from the regular movements of the heavenly bodies; in the mathematically expressed abstractions of eternal cyclical order found in the calendrical system; and most of all, in the understanding of divinity as the fundamental life-force that is, at the same time, the source of all order. Ultimately, this vision reveals itself in the symbolic use of the mask as the most important metaphor for the essentially shamanic presentation of the vision of inner reality to the outer world.

5

The Temporal Order

The Solar Cycles

While the inner vision of the shaman surely showed the way to the essential truth for those who shaped the spiritual thought of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica through the centuries of its development, these speculative thinkers went far beyond their Siberian shamanic forebears in drawing out the mythic, philosophic, and theological implications of that vision. The shamanic world view posited a cosmos governed by an underlying spiritual order growing out of the mythical spiritual unity of all things which both caused and explained the myriad, seemingly disconnected "facts" of the material world, but the causes and explanations characteristic of the prototypical shamanism of the hunting and gathering peoples of Siberia were mystically simple and direct, those perceived by and applicable to the individual in a small group. The spiritual thought of Mesoamerica gradually evolved from that shamanic base into an intricate, subtle, and complex depiction of the revelation of the spiritual order of the cosmos in the world of man. Still apparent in the now centuries-old fragments of that highly developed thought is the sense of wonder with which those inquisitive minds responded to the indications of inherent orderliness which the shamanic vision allowed them to see in the seemingly chaotic world confronting them.

That wonder, as we shall see, is often expressed through the use of the mask as a metaphor for the way in which the harmonious vitality of the life-force underlies the chaotic life of the world of nature. The metaphor of the mask suggests that the natural world, the "mask" in this case, not only covers the animating force of the spirit but also expresses its "true face." Thus, the natural world was seen as symbolic, as pointing, in a way understood by the initiated, to the underlying harmony of the spirit. Those who understood the symbols of the mask could "read" its meaning; the false face became the true face in much the same way the donning of the ritual mask allowed the wearer to express his "true" inner spirit. Although this underlying order was suggested by many kinds of natural "facts," nowhere was it clearer to the seers of Mesoamerica than in the regularity of the numerous cycles through which time seemed to move. Nothing drew their attention more powerfully than this cyclic time; its regularity must have seemed to them nothing less than the force of life itself, the spiritual essence of the cosmos at work. Through the understanding of those cycles, the Mesoamerican sages could figuratively remove the mask of nature, which in all other ways covered the workings of the spirit, and get at the thing itself.

The clearest, and no doubt the first recognized, evidence of this cyclic regularity was apparent in the movement of the sun. That the sun's movement should provide the key to unlock the mysteries of the cosmos makes sense in two quite different ways. First, the most apparent regularity in the external world of nature is provided by the sun's daily rising and setting around which human beings have always organized their lives as it bears an organic relationship to the rhythmic cycle of sleep and waking built into their own bodies. To this organic regularity, however, the shamanistic cultures of Mesoamerica added a second way of seeing the significance of that daily cycle. The endless alternation of day and night no doubt seemed the natural counterpart of and the perfect metaphor for the dualistic nature of the cosmos they envisioned. The presence of the sun during the day must have seemed naturally to represent the waking world of daily existence, sentient activity, logical thought, and physical life. The absence of the sun at night represented the complementary oppo-

site, sleep, which replaced the sentient activity of the daytime world with the fantastic imaginings of dreams, mental rather than physical activity, and the temporary and highly symbolic "death" of the waking person. The daily movement of the sun thus divided the natural world in the same way man felt himself to be divided: into matter and spirit, visible and invisible, living and dead. Tied to the sun's movements, man alternated between his waking, "real" self and his sleeping, dreaming, "spirit" self. This dichotomy within man's very nature, of course, is the same one expressed in the split masks, half-living and half-skeletal, found in Preclassic burials in the Valley of Mexico (pl. 52) which clearly image forth a shamanistic view of life and death as parts of an endless cycle, parts that exist in actuality or in potential at all times. Just as the ability of the shaman to enter the world of death at will suggests the unity of the two states, so the cyclic alternation symbolized by the sun's movement unified those opposed states. That cycle, then, could be seen as an expression of the mystic order of the spirit that alone could make comprehensible the seemingly anarchic diversity of earthly life.

In addition to this daily solar regularity, Mesoamerican thinkers early became aware of and fascinated by the other cycles of the sun. They charted the annual movement of sunrise and sunset along the horizon which resulted in the equinoxes and solstices and noted the regular coming and going of the two instances of the sun's zenith passage each year. The solar cycles were so basic to the concept of time throughout Mesoamerica that among the Maya, for example, the word for sun, kin, also means both day and time.[1] In fact, the day, the most obvious unit of time measured out by the sun, was the smallest unit of time measured in Mesoamerica and was the fundamental unit on which the Maya constructed all the other cycles of time with which they were concerned.[2] The Toltecs and other later groups in the Valley of Mexico saw the solar year as the basic unit, perhaps because their northern origins made them more concerned than the Maya with the annual cycle of seasonal change.[3] The significant fact, however, is that a unit derived from solar movement was used throughout Mesoamerica as the foundation of an elaborate calendrical system designated to chart and understand the force of the spirit as it worked in the natural world.

That such solar observation is of great antiquity in Mesoamerica and that its practice continued with the same intensity until the time of the Conquest (and, in fact, is still practiced by some contemporary Indian groups) can be seen in both the archaeological and written record that survived the Conquest. The great ceremonial centers constructed by the various cultures of Mesoamerica as focal points of the ritual through which they interacted with the natural and supernatural forces of the cosmos were, from the earliest times, laid out on the basis of horizon sightings of solar positions and often contained structures that were designed or oriented to make precise solar and other astronomical observations for ritual purposes. In the Maya Petén, for example, the early pyramid Structure E-VII Sub at Uaxactún

was the western point in group E from which sunrise was observed on the east, marked by three small temples. These temples were aligned on an eastern platform in a north-south line; their northern and southern locations were determined by sunrise at the summer and winter solstices, whereas the location of the central temple was set by sunrise at the equinoxes. . . . Thus Str. E-VII Sub was the viewing point in a solar . . . observatory.[4]

Built during the late Preclassic, this complex served as a model for "at least a dozen sites within a 100 kilometer radius of Uaxactún"[5] and indicates the early importance of solar observation among the Maya. In the Valley of Oaxaca, according to Anthony Aveni, the curiously shaped structure called Mound J built during Monte Albán I (ca. 250 B.C.) was probably used to sight the star Capella, which was used as an "announcer star" for the "imminent passage of the sun across the zenith." The passage could then be observed using a vertical shaft bored into a subterranean chamber aligned with Mound J.[6] Structures similarly suited to astronomical observation of significant moments in the various cycles of the sun are found throughout Mesoamerica. The best known is probably the Caracol at Chichén Itzá, and others have been found at such sites as Mayapán, Uxmal, Paalmul, and Puerto Rico.[7] Significantly, most of the structures probably related to solar observation are ornamented with huge stucco or mosaic masks that seem to denote the importance of the structures and to suggest their role in the solar observation that uncovered the spiritual order of the universe and in the ritual activity through which man harmonized his existence with that universal order.

Such structures were used in laying out the ceremonial centers of which they were a part, and the "cross petroglyphs" found at Teotihuacán evidently served the same purpose there. These markers consist of two concentric circles centered on a cross, the design indicated by a series of holes pecked into a stucco floor or rock. The first such petroglyph was found in a building next to the Pyramid of the Sun, and others were subsequently found at locations suggesting their use by the architects of Teotihuacán to determine the baselines of the grid pattern strictly adhered to throughout the centuries-long construction of the city. The location of the petroglyphs and the resulting location of the baselines indicate that the grid was oriented according to horizon sightings of celestial phenom-

ena related to solar cycles.[8] This solar connection can also be seen in the design of the petroglyph, a quartered circle, found in many contexts and variations throughout Mesoamerica, most of which refer to cycles of time, generally solar cycles.[9] These other symbolic uses of the design suggest that the cross petroglyphs of Teotihuacán were more than surveyor's base marks. They were, symbolically, the order of the city and the order of the cosmos, which it was intended to replicate. As we demonstrate below, they referred directly to the meeting place at Teotihuacán of the worlds of spirit and matter. Just as the rising and setting of the sun on the horizon symbolically denoted that meeting, the line of the cross petroglyph representing the sun's course was bisected by a line perpendicular to it, a line creating the universally symbolic cross designating the center of the universe.

That intersection of the central axis of the universe with the earthly plane marks the point at which the shamanic movement between the worlds of matter and spirit is possible. Hence, the cross petroglyph and the city itself must be seen as symbolic constructions placed on the earth so as to reveal the underlying spiritual order, an order seen most clearly in the essentially spiritual annual cycle of the sun from which the quartered circle was derived.[10] Seen in that way, the cross petroglyph and the city are "masks" placed on material reality, not to cover it but to reveal its spiritual essence—precisely, of course, the function of the shamanistically conceived ritual mask throughout Mesoamerican history. Similar petroglyphs used for the same purpose have been found at widely scattered sites from Zacatecas to Guatemala, most of which had been influenced by Teotihuacán,[11] suggesting the fundamental importance of that symbolic use of the solar cycles as the very fact of diffusion indicates the significance of the design to the people employing it. The structures of ceremonial centers throughout Mesoamerica, then, both in their siting and functions demonstrate the fundamental concern of the builders with the ways in which the regularity of solar movement betrayed the order inherent in the spiritual underpinnings of the natural world.

Further evidence of the concern of Mesoamerican thinkers with the regularities of the cycles of the sun can be seen in the calendrical systems that must have existed well before the Preclassic. The full extent of that calendrical system, one unsurpassed in intricacy and complexity, will be discussed below, but a significant part of the system was, as we would expect, a solar calendar. Made up of 360 days divided into eighteen "months" of twenty days with five "unlucky" days added to complete a 365-day cycle, it was called the xihuitl in central Mexico and the haab by the Maya and provided one of the foundations of the larger calendrical systems. Evidence from Oaxaca suggests it was already in use in the early Preclassic. [12] And we also have evidence of the early existence of one of these larger systems. Called the long count, it computed dates from a presumably mythical starting point corresponding to 3113 B.C. (according to the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson correlation), dates that were recorded on monuments by the Maya and before them by the Olmecs, the probable originators of the system.[13] A number of those dates suggest the antiquity of this elaborate system, among them the date on Stela 2 at Chiapa de Corzo which corresponds to 36 B.C., that of Stela C at Tres Zapotes corresponding to 31 B.C., and the date on the Tuxtla Statuette which corresponds to A.D. 162.[14] Obviously, the systematic solar observations on which the original solar calendar and its elaborate variations were founded must have begun in remote antiquity and been dutifully continued until the Conquest with the numerous dates and calculations of early times no doubt written on perishable materials such as wood, skin, and bark paper. Were these to have survived, they would have testified to the ancient and enduring Mesoamerican fascination with the connection between the regular movement of the sun and the orderly progression of time.

The written evidence that does survive in the codices, the screenfold painted books used for a variety of divinatory and pedagogical functions by the priests and shamans of the various pre-Columbian cultures, suggests in several ways the importance the recording of data related to the solar cycles had in the latter stages of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican development. Many of the Mexican codices contain solar calendars charting the movement of the year through the regular succession of the veintena festivals, the great ritual feasts that ordered the movement of time by denoting the end of each of the eighteen twenty-day periods of the solar year. Fittingly, then, the sun ordered the ritual life of the cultures of central Mexico, a ritual life designed to harmonize man's existence with the life-force symbolized by the sun. The few surviving codices of the Maya are astronomical in nature and offer a rather different sort of testimony to the importance of the sun and its cycles to Mesoamerican spiritual thought as they contain a great deal of astronomical information regarding the cycles of the moon and Venus as well as tables used to predict the possibility of eclipses, all of which were related to solar movement.

Thus, the written evidence of pre-Columbian thought coincides with the evidence from the archaeological record to indicate clearly that the various cycles of the sun were seen throughout Mesoamerica as embodying the spiritual order of the universe. They revealed a unity at the heart of all matter and the way in which the spiritual force emanating from that mystical unity operated in the world of nature. Rather than imagining a god

separate from his creation, the thinkers of Mesoamerica conceived of the divine as the life-force itself, constantly creating, ordering, and sustaining the world.

That force, embodied in and exemplified by the cycles of the sun, not only symbolized the workings of the spirit as it ordered the universe through the magic of time but was also the creator of life, a creation also linked metaphorically to the solar cycles. The sun, as a symbol of the mystical life-force, was seen as the source of all life, a cyclic source that made creation an ongoing process rather than a unique event.

Far from imagining a sure and stable world, far from believing that it had always existed or had been created once and for all until at last the time should come for it to end, . . . man [was seen] as placed, "descended" (the Aztec verb "temo" means both "to be born" and "to descend"), in a fragile universe subject to a cyclical state of flux, and each cycle [was seen] as crashing to an end in a dramatic upheaval.[15]

This cyclic process of creation and destruction is recorded in the pan-Mesoamerican myth cycle of the Four (or Five) Suns which identifies each stage in the ongoing process of creation as a sun, one stage in a solar cycle. The basic myth is simple; in its Aztec version, the present age, that of man and historical time, is the Fifth Sun. The first of the four preceding periods, the First Sun, identified by the calendric name 4 Océlotl, or 4 Jaguar, saw the creation of a race of giants whose food was acorns. That age ended with their being devoured by jaguars, often a symbol of the night sky and thus the dark forces of the universe. The Second Sun, 4 Ehécatl, or 4 Wind, peopled by humans subsisting on piñion nuts, ended with a devastating hurricane that transformed the people who survived it into monkeys. This age was associated with Quetzalcóatl in his aspect of wind god, Ehécatl. The Third Sun, 4 Quiáhuitl, or 4 Rain, was naturally associated with Tlaloc and had a population of children whose food was a water plant. It was destroyed by a rain of fire from the sky and eruptions of volcanoes from within the earth with the surviving inhabitants changed into turkeys. The Fourth Sun, 4 Atl, or 4 Water, was populated by humans whose food was another wild water plant. It was destroyed by floods, as its association with Chalchiúhtlicue, the goddess of bodies of water, would suggest. The survivors of the destruction appropriately became fish. The present world age, the Fifth Sun, 4 Ollin, or 4 Motion, is destined to meet its end by earthquake.

This basic myth, so clear and direct on the surface, is fascinating in its subtle interweaving of the shamanistic idea of the life-force with the Mesoamerican conception of the solar cycles as representative of the inherent order of that essentially spiritual life-force. Both the daily and annual cycle of the sun are basic to the myth's conception of creation. The concept of five successive suns suggests the diurnal cycle of the sun with the awakening of life in the morning of each day and the "death" of life at day's end, a suggestion emphasized in the destruction of the First Sun by the jaguar, a symbol of the night. Just as awakening from sleep provides a model for creation, so the "awakening" of plant life in the spring provides another basic metaphor suggested by the care with which the myth specifies the sustenance provided for humanity in each of the world ages; it is always a plant that springs from the earth itself to provide nourishment. Thus, the earth functions as a repository of the life-force, which is "awakened" by the solar cycle in the spring in order to create the life that in turn sustains human life. The significance of the sun is underscored by the identification of corn in the present world age as the divine sustenance of humanity, suggesting at once the Indian's almost mystical reverence for that grain and the process of growing it, the reciprocal relationship between humanity, nature, and the gods, and the relationship between the life cycle of the individual plant and the sun, a connection that pervades the mystical attitude toward corn in the mythologies of Mesoamerica. The myth of the Five Suns thus directly involves the cycles of the sun in the generation of life on the earthly plane by the life-force that lies at the heart of the universal order.

But the solar cycles are only part of a larger conception of creation. Life in the Fifth Sun is created by Quetzalcóatl from bones and ashes of the previous population which he was able to gather during a shamanlike journey to the underworld, the hidden world of the spirit entered only through a symbolic death to the world of nature. The shamanic nature of this creation is further suggested by the metaphoric reference to the belief that the life-force in the creatures of this earth resides in the bones, the "seeds" from which new life can grow. To create that life, Quetzalcóatl pierced his penis and mixed the blood resulting from that autosacrificial act with the pulverized bone and ash from the underworld. Symbolically, his creative act unites the shamanistic belief that the bones are the repository of the life-force with the Mesoamerican view that blood represents the essence of life, a view especially clear in this case since the blood is drawn from his penis, the source of semen, man's reproductive fluid. Creation is seen in a series of organic metaphors bringing together seeds and bones, the sun and birth, man and plants in a complex web of meaning suggesting the equivalence of all life in the world of the spirit, which underlies and sustains the world of nature. Life in this world, the myth suggests, must be understood in terms of that underlying spirit.

The evidence we have of Maya thought reveals a remarkably similar cyclic conception. In the

Popol Vuh , the mythic history of the Quiché Maya of highland Guatemala, the creation of life, or "the emergence of all the sky-earth," is described as

the fourfold siding, fourfold cornering,

measuring, fourfold staking,

halving the cord, stretching the cord

in the sky, on the earth,

the four sides, the four corners.

In other words, a quadripartite creation

by the Maker, Modeler,

mother-father of life, of humankind,

giver of breath, giver of heart,

bearer, upbringer in the light that lasts

of those born in the light;

worrier, knower of everything, whatever there is:

sky-earth, lake-sea.[16]

Attempting to create man, the gods three times formed creatures incapable of proper worship; only on the fourth try were they successful. First, birds and animals were created, but they could not speak to worship their creators "and so their flesh was brought low"; they were condemned thereafter to be killed for food. The second attempt resulted in men made from "earth and mud," but it was equally unsuccessful because they had misshapen, crumbling bodies; their speech was senseless so that they, too, were incapable of the worship required by their creators. After destroying these men, the gods next fashioned "manikins, woodcarvings, talking, speaking there on the face of the earth," but their speech was equally useless because "there was nothing in their hearts and nothing in their minds, no memory" of their creators. These manikins were destroyed by a flood and the combined efforts of the animals, plants, utensils, and natural objects they had ungratefully used. Those surviving the destruction became the present-day monkeys.[17]

Following this third unsuccessful creation, the Popol Vuh narrates the lengthy exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque in the underworld, exploits comparable in mythic function to Quetzalcóatl's shamanic descent into the underworld in the cosmogony of central Mexico (significantly, one of the meanings of Quetzalcóatl is "Precious Twin"). Following those exploits, historical man, the Quiché, was created from the life-giving corn and thereby linked to the annual seasonal cycle. "They were good people, handsome," and "they gave thanks for having been made." But this time the gods had succeeded too well. These men were godlike: they could see and understand everything. In order to put them into their proper relationship to their makers, "they were blinded as the face of a mirror is breathed upon. Their eyes were weakened. . . . And such was the loss of the means of understanding, along with the means of knowing everything, by the four [original] humans."[18]

Although neither the account in the Popol Vuh nor the similar account in The Annals of the Cakchiquels, the neighbors and enemies of the Quiché Maya, suggests the eventual destruction of the present world age, there is a reference to such a destruction by Mercedarian friar Luis Carrillo de San Vicente, who said in 1563 that the Indians of highland Guatemala believed in the coming destruction of the Spaniards by the gods, after which "these gods must send another new sun which would give light to him who followed them, and the people would recover in their generation and would possess their land in peace and tranquility."[19] This belief indicates the close similarity between the cycles of the Maya cosmogony and those of central Mexico. Miguel Le6n-Portilla points out that essential similarity when he writes that for the Maya, "kin, sun-day-time, is a primary reality, divine and limitless. Kin embraces all cycles and all the cosmic ages. . . . Because of this, texts such as the Popol Vuh speak of the 'suns' or ages, past and present."[20] Robert Bruce makes that idea even clearer. The Popol Vuh, he says, consists of "the same cycle running over and over," and that cycle is "the basic cycle, the solar cycle [that] pervades all Maya thought."[21] Thus, both the Popol Vuh and the Aztec myth depict a reality grounded in the spirit whose essential order is revealed by the cycles of the sun. It is no wonder that throughout Mesoamerica even today, Indians who think of themselves as Christians identify Christ, whose death allowed him to enter the world of the spirit, with the sun as the very epitome of the spirit as it moves in the world of nature.

The Mesoamerican fascination with the sun is further shown by the fact that insofar as the thinkers of Mesoamerica were interested in other celestial bodies, they were almost exclusively interested in those whose cyclic movements were apparently related to the sun. Thus, the two other bodies most often of concern were the moon and Venus. In view of the important role the moon plays in many mythologies, it perhaps seems strange that, as Beyer observed, the moon played a relatively "insignificant role in the mythological system encountered by the conquistadores."[22] Two myths from central Mexico at the time of the Conquest indicate clearly that whatever importance the moon had derived from its role in a predominantly solar drama.

The first of these myths depicts the creation of the current sun and moon shortly after the beginning of the present world age. In one of its versions, two gods—Nanahuatzin, poor and syphilitic, and Tecciztécatl, wealthy, handsome, and boastful—volunteer to throw themselves into a great fire in a sacred brazier which will purify and allow them to ascend as the sun and light the world. Tecciztécatl proves too cowardly to leap, but Nanahuatzin does and rises gloriously as the sun. Following Nanahuatzin's success, Tecciztécatl musters

his courage, immolates himself, and becomes the moon. True to his boastful nature, Tecciztécatl at first shines as brightly as the sun, but the remaining gods throw a rabbit in his face (what European culture sees as the image of an old man on the face of the moon was seen throughout Mesoamerica as a rabbit) to dim him to his present paleness.[23] In addition to the obvious oppositional relationship of the sun and moon—one the ruler of the day sky, the other of the night; one bright, the other pale; one retaining a consistent shape, the other changing—this myth suggests other oppositions that would have been of particular importance to the Aztecs, who saw themselves as the people of the sun, a warrior sun who symbolically led their nation. Nanahuatzin, ugly and disfigured on the surface, embodied the inner virtues they prized: courage, modesty, dedication; Tecciztécatl, superficially handsome and seemingly brave, was actually a cowardly braggart. The myth finds reality beneath the surface of appearances, and the fact that this truth is contained in a myth concerned with the creation of the sun and moon is amazingly appropriate as the sun and its various cyclic movements, including the cycle in which the moon participates, provided an understanding of and a metaphor for the underlying order of the cosmos for the Mesoamerican mind. As the myth suggests, the inner truth is most significant; one must look beneath the surface of reality in this more profound sense to understand the essential meaning of the world of appearances.

The second myth also delineates the basic opposition between the sun and moon within the cycle of day and night. Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec tutelary god, was said to have been conceived by Coatlicue, the earth goddess, when "a ball of fine feathers" fell on her. Her pregnancy was seen as shameful by her children, Coyolxauhqui and the four hundred (i.e., countless) gods of the south, and they resolved to kill her. Huitzilopochtli, still in her womb, vowed to protect his mother. As the four hundred, led by Coyolxauhqui, approached, Huitzilopochtli, born at that moment, struck her with his fire serpent and cut off her head. Her body "went rolling down the hill, it fell to pieces," and her destruction was followed by Huitzilopochtli's routing her four hundred followers and arraying himself in their ornaments.[24] As numerous commentators from Eduard Seler and Walter Krickeberg on have said, this myth clearly depicts the daily birth of the sun and the consequent "destruction" of the moon and stars as the sun replaces them in the sky. The dismemberment of Coyolxauhqui also suggests the moon's various phases as it waxes and wanes as well as its disappearance between cycles.

This myth also depicts the sun, with the virtues of the warrior, in opposition to the moon, this time female, which lacks them: Huitzilopochtli defends his mother, Coyolxauhqui betrays her; he stands alone bravely, she acts only with many followers. But here the implications go much deeper. Significantly, the moon is here depicted as female, and much of the myth's meaning turns on that opposition between male and female. For example, the myth portrays Huitzilopochtli's vowing to defend his mother as taking place while he is still in her womb, making clear that his birth from the female immediately precedes his destruction of his female sibling, an act in structural opposition to his birth: a female gives him birth; he takes a female life. But the Aztecs knew that with the coming of night he too would be destroyed, metaphorically, by being swallowed by the female earth. This further reversal (he destroys a female and is then destroyed by one) suggests the nature of the cycle in which the sun and the moon exist and also suggests the nature of cosmic reality, which both creates and destroys life, a cyclic reality also connected with the sun in the creation myth of the Five Suns.

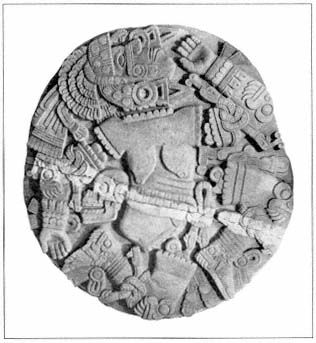

The recent discovery of the monumental Coyolxauhqui stone (pl. 59) at the base of the pyramid of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlán confirms this thesis and suggests several other implications as well. The stone depicting the dismembered goddess was uncovered at the foot of the stairway leading up to the Temple of Huitzilopochtli atop the pyramid, a placement recalling the myth in which her body rolls down the hill and falls to pieces. When the sun is at its midday height, suggested by the temple at the top of the pyramid, the moon will be in the depths of the underworld, the land of the dead. But the Aztecs knew that just as the coming of the night would reverse those positions and states, so their own individual vitality, their nation's preeminent position in the Valley of Mexico, and the world age—the Fifth Sun—in which they lived would all eventually perish in the cyclic flux of the cosmos, only to be reborn, though perhaps in a different form. Thus, the killing of Coyolxauhqui paradoxically guarantees the rebirth of Huitzilopochtli and the continuation of the cosmic cycle of life, just as the sacrifice of captured warriors on the stone found by archaeologists still in place in the Temple of Huitzilopochtli and the rolling of their dead bodies down the pyramid to the stone of Coyolxauhqui at the base was seen by the Aztecs as vital to the continuation of their life and the life of the sun.

It is interesting that Huitzilopochtli's temple shared the top of the pyramid with the Temple of Tlaloc. Tlaloc, the god of rain, and the female Coyolxauhqui both have an association with fertility that opposes them to Huitzilopochtli, who is, after all, a male war god. But the myth suggests again the alternation that characterizes the daily cycle of the sun and the moon. Although associated in one sense with fertility, both Tlaloc and Coyolxauhqui also have a destructive aspect. Co-

Pl. 59.

Coyolxauhqui, Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlán

(Museo del Templo Mayor, México).

yolxauhqui's role in the myth is destructive, not creative, and Tlaloc's rain could fall in the destructive torrents of a tropical storm. In both of these cases, Huitzilopochtli can be seen again in an opposing, but this time creative, role—that of the defender of his mother and as the life-giving sun. On a profound level, then, the myth of the destruction of the moon by the sun is clearly meant to delineate the cyclic alternation between life and death, creation and destruction which seemed to the Mesoamerican mind to characterize the rhythmic movement of the cosmic cycles for which the sun provided a metaphor. The two opposed forces become one within the cycle just as the feathered headdress of Coyolxauhqui on the monumental relief at the Templo Mayor (pl. 59) suggests her ultimate union with Huitzilopochtli, her brother, "the divine eagle of the sky." The feathers are "signs of the union consummated through sacrifice" and illuminate "the manifest duality that reveals the essential unity of the god and the victim,"[25] of the sun and the moon, of life and death—the unity originally perceived by the shamanic forebears of Mesoamerica and the same unity celebrated by the metaphoric use of the ritual mask to symbolize the union of matter and spirit.

Both of these myths depict the moon as subordinate to the sun, and in both myths, the underlying meaning reinforces that subordination. For the Aztecs, the moon was not important in itself but only as its opposition could be seen to clarify the sun's role and symbolic meaning. The situation among the Maya was much the same. In the Popol Vuh, at the end of the underworld adventures of the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque, "the two boys ascended ... straight on into the sky, and the sun belongs to one and the moon to the other,"[26] a parallel to the Aztec myth of Nanahuatzin and Tecciztécatl at least in the fact that two male gods are transformed. But as in the Valley of Mexico, myths also exist among the Maya which depict the moon as female in relation to a male sun. According to Thompson, they are the norm and for contemporary Maya groups, at least, usually depict the sun and often a brother, Venus, hunting to provide food for the family. But the old woman at home, often their grandmother but always the moon, "gives all the meat they bring home to her lover. The children learn this, slay her lover, and trick the old woman into eating part of his body. She tries to kill the children, but they triumph . . . and kill her."[27] This generalized version has interesting structural similarities with the Huitzilopochtli Coyolxauhqui myth, which, with its wide distribution with many variants among the contemporary Maya, indicate its pre-Columbian origin. Both myths depict the sun as a male child in the position of supporting the ideal of sexual virtue, both depict the moon as female and as betraying a parent or child, and both, of course, depict the destruction of the moon by the sun. The emphasis on sexuality in the Maya myth parallels the emphasis on birth in the Aztec version; both focus on generation and death, and, by implication, regeneration. Thus, it is fair to say that both call attention to the basic cyclic alternation between opposed states in the cosmos and to the unity underlying and governing the cycle.

The emphasis on the regularity of the solar and lunar cycles in the understanding of the cosmic unity would seem to indicate a need to deal with the phenomena of eclipses since they are clearly disruptions of those all-important cycles, and Mesoamerica did deal with them at some length. The suggestion in the Maya myth that the moon eats part of the body of her lover (alter ego of the sun?) is interesting in this context. A passage from the Chilam Balam of Chumayel describing the disastrous events of Katun 8 Ahau reads: "Then the face of the sun was eaten; then the face of the sun was darkened; then its face was extinguished,"[28] which is echoed by the Chorti Maya belief that an eclipse is caused by the god Ah Ciliz becoming angry and eating the sun.[29] Though these are post-Conquest beliefs, they reflect the pre-Columbian fascination with and fear of eclipses. Throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, it was believed that both solar and lunar eclipses were disastrous portents signaling destruction, possibly even the end of the world, that is, the present world age or "Sun," just as the setting of the sun ended the day and the disappearance of the moon "destroyed" the night. The Maya Dresden Codex contains tables used to predict the dates of possible eclipses, tables that reflect the

working out by the Maya of the complex cycles that governed them. Given the cosmic importance Mesoamerica attributed to the cycles of the sun and, to a lesser extent, the moon, any interruption of them would seem to shake the very foundation of the universe. Interestingly, the Maya attempted to secure that foundation by finding a regularity in the occurrence of these seemingly unpredictable events, thereby including them within the cyclic nature of reality. Everything, they must have believed, when properly understood manifested the order derived from the spiritual unity underlying all reality.

The only other celestial body with which the peoples of Mesoamerica were greatly concerned was Venus. It is "the only one of the planets for which we can be absolutely sure the Maya made calculations"[30] and probably the only one that played a major role in central Mexican mythology. The reason for this, according to Aveni, is that "besides Mercury it is the only bright planet that appears closely attached to and obviously influenced physically by the sun."[31] This apparent "attachment" derives from the fact that its solar orbit lies between the earth's orbit and the sun. From the vantage point of the earth, Venus's movement can be divided into four distinct periods: (1) the period of inferior conjunction—an 8-day period when Venus is directly between the sun and the earth and thus invisible because of the sun's glare; (2) the period in which it is the morning star—a 263-day period during which the planet is most brilliant and rises before the sun in the eastern sky, at first only a moment before the sun, the annual moment of heliacal rising after inferior conjunction of utmost importance to Maya astronomers, and then for longer periods each day, the last and longest being about three hours; (3) the period of superior conjunction—a 50-day period during which the sun is between Venus and the earth; (4) the period in which it is the evening star—a 263-day period in which it is visible for a short time in the western sky after sunset, each day for a shorter period of time until inferior conjunction occurs and the cycle begins again. "The long-term motion of Venus can thus be described as an oscillation about the sun, the planet never straying far from its dazzling celestial superior."[32]

Not only was Venus tied visually to the sun but there were numerical relationships as well which fascinated the Mesoamericans. It was known throughout Mesoamerica that the synodic period described above took "584 days, the nearest whole number to its actual average value, 583.92 days and that 5 × 584 = 8 × 365 so that 5 synodic periods of Venus exactly correspond to 8 solar years."[33] In addition, there were further numerical correspondences, which are discussed below in connection with the 260-day calendar. Suffice it to say that the apparently eccentric motion of Venus actually meshed with the all-important solar cycles in a number of ways, suggesting again the basic order underlying the apparent randomness of the cosmos.

Among the Maya, "the main function of the study of Venus seems to have been to be able to predict the time of the feared heliacal rising after inferior conjunction," which could cause sickness, death, and destruction.[34] These dire predictions parallel those seen in the Codex Borgia of the Valley of Mexico,[35] and it seems likely that the Maya got these ideas from central Mexico[36] where the period of inferior conjunction was associated with Quetzalcóatl. Both mythologically and historically, in different contexts, his disappearance and reappearance under changed circumstances is central to his story. According to the Anales de Quauhtitlán ,

at the time when the planet was visible in the sky (as evening star) Quetzalcóatl died. And when Quetzalcóatl was dead he was not seen for four days; they say that then he dwelt in the underworld, and for four more days he was bone (that is, he was emaciated, he was weak); not until eight days had passed did the great star appear; that is, as the morning star. They said that then Quetzalcóatl ascended the throne as god .[37]

Quetzalcoatl's rebirth in shamanic fashion—from the bone as seed—thus accords with the sacred heliacal rising of Venus after inferior conjunction, when its rising first heralds the rising of the sun in the east (the direction of regeneration) and his death with the disappearance of the western, evening star, itself a symbol of the death of the sun. Quetzalcóatl's very name, translated as "Precious Twin" as well as "Feathered Serpent," suggests this connection with the two aspects of Venus. According to Seler, the Codex Borgia includes "myths concerning the wanderings of the divinity [of the morning star] through the underworld kingdoms of night and darkness" during the period of inferior conjunction which are similar to the wanderings of the Hero Twins in the Popol Vuh ,[38] wanderings that Coe sees as "an astral myth concerning the Morning and Evening Stars."[39] Thus, it is the period of inferior conjunction, when Venus seems to merge with the sun, and the following heliacal rising, when its rebirth heralds the rebirth of the sun, that fascinated Mesoamericans, a fascination clearly due to the interplay of Venus and the sun.

Surely, then, it is clear that when the seers of Mesoamerica looked to the heavens they saw a cosmic order revealed in the myriad, intricate cycles that meshed with the regular movement of the sun. This order became the basis of myths and rituals, the calendar that organized the ritual year, and the principle from which was derived the orientation of the great ceremonial centers in which those rituals took place. Everywhere one turns, one finds evidence in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica of the at-

tempt to replicate the order of the sun's cycles in man's earthly world and through that replication to understand the workings of the inner life of the cosmos, an understanding fundamental to Mesoamerican cosmology and cosmogony and an understanding for which the mask stood as metaphor.

Generation, Death, and Regeneration