The "Intellectualization" of the Citizen Portrait

A brief look at the imagery of the ordinary citizen in Late Hellenistic art will make clear that we are dealing here with a reciprocal process. At the same time that the distinguishing characteristics of the philosopher portrait become less pronounced, citizens of the Greek cities put the emphasis on learning and a contemplative nature in their own self-image. From the second century on, reading and contemplation are

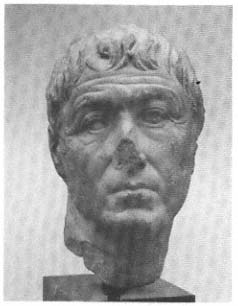

Fig. 100

Portrait of a contemplative citizen, from a

Late Hellenistic funerary or votive monument.

Athens, National Museum.

seen as outstanding values and appropriate motifs for the representation of a male citizen on his tomb monument. It is only against the background of this intellectualization of everyday life that we can understand the place of the retrospective portraits within this cultural system.[45] A number of portraits of the later second century from Delos, Athens, and elsewhere have a markedly contemplative expression. Occasionally a raised brow seems to allude directly to the appearance of Carneades or another philosopher (fig. 100).[46] We have already observed the beginnings of this process of assimilation in the portraiture and grave reliefs of the Late Classical period (cf. pp. 67ff.). Now, however, it becomes much more apparent and is no longer limited to older citizens.

The contemplative expression is, however, often combined with a dramatic turn of the head and other formulas that denote energy

and determination, derived from the repertoire of contemporary ruler portraits. The citizen male evidently sought to portray himself as a combination of philosophical meditation and energetic vitality, or, in more personal terms, a combination of the new intellectual hero of the polis and the dynamic and beneficent monarch. The resulting ambiguity is perhaps reflected in the oddly contradictory appearance of certain heads.[47]

The description of this physiognomy as "contemplative" would be no more than a subjective impression if we did not have other evidence of the central importance of philosophy scholarship, and learning that helps give voice to these "contemplative" men. We have already noted the significance of the gymnasia, as well as the appearance of learned motifs on objects of daily use and even in the painted decoration on the walls of private homes. A particularly valuable testimony is the widespread adoption of the imagery of paideia on the funerary reliefs. These are preserved in large numbers, especially from the cities of Ionia, and provide direct evidence of the way in which a broad stratum of the bourgeoisie wished to see itself represented.[48]

The first thing we notice on these reliefs is the large number of book rolls and writing tablets and implements. These meaningful attributes are displayed on shelves, presented by slaves, and of course also held by the deceased and others. They may belong to youths of school age, to men in the prime of life, or to old men, and even some women are also celebrated in this manner for their paideia . The epigrams accompanying the reliefs confirm that such attributes do refer specifically to the notion of learning and education. The virtues of a "universal" learning are suggested in the plethora of volumes, often depicted in bundles or stored in a case.

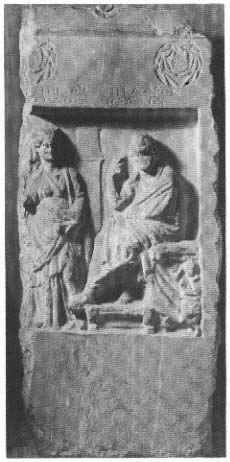

In addition to this general praise of learning through the use of attributes, there are also more explicit images, particularly from those cities that have left us the largest number of grave stelai. For example, in Smyrna, Cyzicus, and Delos, it is not unusual for an older man to be depicted as a seated "thinker." His authority may be expressed in his elevated position or in the lavish and dignified chair on which he sits. On a fine stele now in Winchester (fig. 101), a citizen of Smyrna gives instruction looking down from his elevated seat, the fingers of his right hand ticking off the arguments. His face, with its look of

Fig. 101

Grave stele from Smyrna. Second

century B.C. Winchester College.

concentration, is turned not to his wife, but to the viewer. As in the portrait of Chrysippus, the image speaks directly to the viewer. The female figure, as on many of these stelai, stands in casual proximity to the "philosopher," her appearance recalling that of a priestess of Demeter. This suggests that in her role as wife, she is celebrated above all for her piety.[49]

It is no accident that the image of the seated man calls to mind that

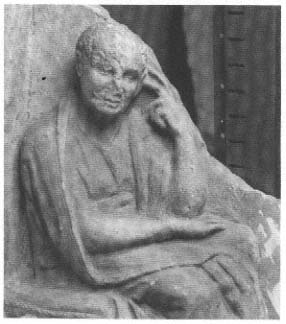

Fig. 102

Grave stele of an elderly citizen from Smyrna.

Second century B.C. Leiden, Rijksmuseum.

of Chrysippus (fig. 54). Other stelai as well betray a visual association with well-known statues of poets and philosophers of the third century. Interestingly, the most popular motif is that of meditation with the head propped up on one hand, in the manner of the philosopher in the Palazzo Spada and the bronze statuette of Kleanthes (cf. fig. 58), which has the effect of distancing the thinker from the world outside. A particularly fine example, again from Smyrna, shows an old man with markedly individualized features and the unmistakable expression of a thinker (fig. 102).[50]

Such instance are not, however, deliberate quotations of famous monuments. Rather, the familiar images of mental and intellectual activity created in Early Hellenistic art had simply become ingrained in the popular consciousness, along with their connotations of dignity and authority. That these images were indeed understood as signs of

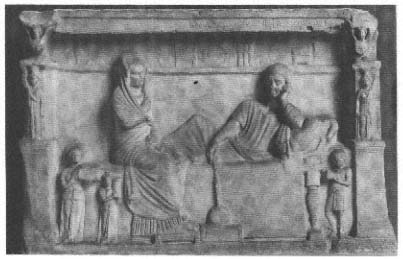

Fig. 103

Grave stele from Byzantium. First century B.C. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum.

outstanding intellectual ability or achievement is confirmed by the fact that the men so depicted can in many instances be shown to have held an office in the gymnasium.[51]

In the course of the later second and first centuries B.C. , the imagery of paideia becomes widespread in the funerary art of Hellenistic cities. In Byzantium, for example, the venerable image of the "Totenmahl" (funerary banquet) relief is transformed into what we might call a "Bildungsmahl." Tables and shelves are filled not with food, but rather food for thought: book rolls and writing implements. Cultivated gentlemen hold open book rolls instead of drinking vessels, and one even seems to be playing the part of one of the Seven Wise Men, the scholar and astronomer expounding on the globe with his pointer (fig. 103).[52] The familiar look of contemplation here gives him a rather self-satisfied appearance. It is worth noting that this motif of the "Bildungsmahl" seems to appear in Byzantium on the largest and artistically most ambitious grave stelai. It is, in other words, the upper class that so insistently lays claim to the value of learning, even in a city that

at this time was still on the margins of Greek cultural life. At one time, in the third century B.C. , such images, attached to pioneering thinkers, were seen as a challenge to society and to traditional political and social ideas, a harbinger of a new way of thinking. Now the image looks merely blasé, the very essence of acceptable behavior among the established bourgeoisie.