Part One: The House

In a creative study of the local Colombian economy, Stephen Gudeman (1990) suggests the house as an alternative to the model of the corporation. He argues that Colombian peasants use a model of the house to organize their social and economic lives, and he defines the house primarily in opposition to the model of the corporation, which he believes coexists in dialectical tension with the house. Gudeman holds that the house economy is an institution of such long standing that it preceded historically the development of the market and its corporate organization (1990:9). He also contends that the notion of a house economy has widespread applicability and relevance and thus asks whether, in rethinking the corporation as a model for local forms of organization, we might modify the use of that model in African studies as well.

The corporate model upon which lineage theory is based is a specifically Western model that has been imposed on others at the expense of their folk models. The house, in contrast, seems to represent the way that many people conceive of and model their own economies. In fact, one of the ancestors of descent theory, Evans-Pritchard (1940), reveals that the Nuer do not conceive of their social world in terms of a lineage model. For example, in 1933, Evans-Pritchard posed the question: "What exactly is meant by lineage and clan? One thing is fairly certain, namely, that the Nuer do not think in group abstractions called clans. In fact, as far as I am aware, he has no word meaning clan and you

cannot ask a man an equivalent of 'What is your clan' " (1933, part 1:28). In The Nuer , Evans-Pritchard offered a definition of lineage that has little to do with corporate or descent groups: "A lineage is thok mac , the hearth, or thok dwiel , the entrance to the hut" (1940:195). For Evans-Pritchard, then, lineage was the model for the hearth and home. But might the hearth and home, rather than the descent group and lineage, be the Nuer models for political opposition? Might the lineage be an imposition of a European corporate model? Or might there be, as I argue for the Lese, two or more coexisting models—say, a descent model for one set of social processes, a house model for another set? Gudeman notes,

One can only wonder how the history of descent theory might have appeared had theorists of the 1940's, instead of exporting their own market experience, used a model of the home and the hearth, as Evans-Pritchard's own foundational work suggested (1940:192, 195, 204, 222, 247; 1951:6, 7, 21,127, 141), or the local imagery of kin groupings. We might never have established such trust in the existence of the corporate descent group or even, for that matter, the lineage. (1990:184)

Gudeman's emphasis on the house helps us to find models that reflect local conceptions of social organization rather than those tendentiously formulated by anthropologists. But if a house model is to advance our ethnographic understanding, we have first to distinguish our use of the term "house" from other uses.

The importance of the house as a primary unit of social organization, or even as a model for the larger social order, has never been questioned in anthropology. Not only have ethnographers clearly pointed out that the architecture of the house is related directly to both cosmology and social organization (see Morgan 1881; Bourdieu 1971; Fernandez 1976; Feeley-Harnik 1980; J. Comaroff 1984; Blier 1987; J. Comaroff and J. L. Comaroff 1991), but also there is a strong interest in reconceptualizing the organization of some societies, especially Indonesian and Indo-European societies, as being of the "House" type (Lévi-Strauss 1979; Errington 1987; Pak 1986; Schloss 1988), or what Lévi-Strauss calls "Société à Maisons." In addition, there is a rich and extensive literature on households and their economic functions (see, for example, Guyer 1981; Wilk 1989, Heald 1991).

Lévi-Strauss notes the existence of societies throughout the world whose units of social organization are not easily defined by terms such as "family," "lineage," or "clan," as they have been used conventionally in anthropology. Unfortunately, the anthropology of Boas and

Kroeber, he says, "did not offer the concept of the house in addition to that of tribe, village, clan and lineage" (1979:174). Lévi-Strauss sees in the house an institutional form for the mediation of conflicting social structural principles, such as patrilineal and matrilineal descent, filiation and residence, hypergamy and hypogamy. This view has been followed by S. Errington (1987) in her study of how the house resolves contradictions between brothers and sisters in Indonesia, and by J. A. Boon (1990) in his study of Balinese twins.

It is clear that the "house," as developed in this literature, is suited to the characteristic kinship contradictions in island Southeast Asia, many of which are managed or reunited at the level of the house. But the concept of the house, in whatever context it is elaborated as a unit of social analysis, can help repair some of the problems associated with the preoccupation with descent rules, and it can illuminate new aspects of social organization and its symbolic representation. In Indonesia, for example, whereas a focus on descent would emphasize the differences between societies with distinct kinship patterns, a focus on the house reveals important continuities between unilineal and nonunilineal and exogamous and endogamous societies—according to Boon (1990), these may be transformations of one another. For the Lese, the conception of the house, as we shall see, leads us to consider social relationships and ideas obscured by descent; namely, the role of gender and inequality in constituting ethnic differentiation within the economy.

Despite the centrality of the household in the economic anthropology of Africa, a house model has not been systematized, and where it has appeared as a central metaphor it is usually employed as a component of descent organization (see Schloss 1988; Jones 1963; Mitchell 1956; Lloyd 1957). M. R. Schloss (1988) views the houses of the Ehing of West Africa as constituting distinct descent groups, and G. I. Jones (1963) and J. C. Mitchell (1956) analyze houses as constituted by unilineal extended families. In these cases, the house is not a local model for the society and the economy but rather an institution, a component of social structural systems, such as lineages and descent groups, whose relevance is to be found "on the ground" rather than in the realm of cultural modeling. The Lese house is relevant to both contexts. For the Lese and the Efe, the Lese house is where production, consumption, and distribution take place. Indeed, the house is the physical locus of economic interaction between the Lese and the Efe. But the house is also the locus of the symbolic organization of relations of inequality, including relations of ethnicity and gender. The house, then, is not only

a component of larger sets of social relations but a model that has to do with the conceptual organization of relations of difference as well as the organization of social practices. My treatment of the house and descent falls more in line with a few exceptional works in African anthropology: Enid Schildkrout's analysis of the domestic context of multiethnic communities in urban Ghana (1975, 1978), Jan Vansina's and Curtis Keim's political histories of the equatorial rain forest in central Africa (Vansina 1982, 1990a, 1990b; Schildkrout and Keim 1990), and M. Saul's recent study of the Bobo house in Burkina Faso (1991). Schildkrout finds that, in Ghana, social and cultural integration of ethnically diverse persons takes place in a domestic context, and Vansina and Keim both find that a house model of social organization among central African forest peoples made possible two contrasting ideological principles: the lineal and egalitarian groupings on the one hand, household and hierarchical groupings on the other. I will discuss these authors in more detail below. For Saul, the house, like descent, is a metaphor, a way of "expressing the idea of regroupment in space" (1991:78); for the Bobo, social behavior and political and economic rights are shaped by the house metaphor, but also by a number of other organizational principles, including descent and other patrilineal associations. For the Lese, too, the house is not the only conceptual system for social organization and classification, but the Lese restrict the organization of certain relationships (gender and ethnic) to the house, and others (those between Lese agnates and Lese men) to the clan, phratry, or lineage. These restrictions contrast with the social organization of the Bobo, for whom, as Saul notes, ritual and land associations, among others, can be based on any of a variety of organizational principles—as he calls it, "a kind of political game" (1991:97).

The house, as I shall use it, is also distinct from "family" or "household" in the sense in which these terms are generally understood—that is, the two terms are frequently distinguished, with the former referring to genealogically defined relationships, the latter referring to coresidence or propinquity (Yanagisako 1979). In the Lese-Efe case, however, houses are not defined by coresidence so much as by membership, with membership founded on common participation in the production and distribution of cultivated foods. Indeed, Efe men seldom reside or even sleep in their Lese partner's houses, but they are still considered house members. Because the partnership, and therefore house membership, is defined through individual Lese and Efe men, the children of Efe partners are not considered members of the house. Yet, at the same time,

Efe children often live in their father's Lese partner's house. Thus, neither lineage, propinquity, nor the family defines the Lese house.

One further point: it is frequently assumed that households have well-defined functions and have easily definable boundaries, yet the functions, activities, and organizations of households vary widely. In spite of all this cultural variation, "household" is still generally taken to be a uniform concept across cultures. S. J. Yanagisako, for example (1979:165), says: "Generally, [household] refers to a set of individuals who share not only a living space but also some set of activities. These activities, moreover, are usually related to food production and consumption or to sexual reproduction and childrearing, all of which are glossed under the somewhat impenetrable label of 'domestic' activities." And she points out that, because "all the activities implicitly or explicitly associated with the term 'household' are sometimes engaged in by sets of people who do not live together" (p.165), several anthropologists have suggested using alternative terms—such as "domestic group" (Bulmer 1960)—to refer to persons who acknowledge a common domestic authority: "co-residential groups" (Bender 1967) to designate propinquity, more specifically, and "budget unit" (Seddon 1976) to distinguish economic functions from coresidence.

I use an alternative term, "house," for a number of reasons. First, and most importantly, this is the best translation of the term ai , which the Lese use to describe the actual structure within which people live and within which economic activities are organized. Second, given the assumptions of coresidence inherent in the conventional use of the term "household," "house" is a less confusing term. Third, I do not wish to dichotomize a coresidential or domestic unit from a politico-jural domain. The house integrates entire ethnic groups and so has to be seen as part and parcel of the political and economic structures of society. Yanagisako (1979) and H. Moore (1988) note that anthropologists have only recently begun to explore relations of inequality within households as constitutive of domestic organization. Since the Lese house contains within it members of different ethnic groups, ages, and genders, it goes even further to draw our sights toward relations of social and political inequality at the level of the ethnic group.

Finally, although the term "house" as I use it in this study refers to an actual structure, it also refers to a model that has to do with the conceptual organization of ethnic and gender relations, as well as the organization of social practices. As I suggested in the Introduction, it is a source of core symbols as well as an arena for interactions structured by them. As for Gudeman, the model is a "detailed working out or

application" of a series of metaphors. A wide range of societies may model their society and economy after the house, but the house still remains a local model that we should not expect to find duplicated exactly in other contexts. The anthropologist should understand the "cultural sense" of each house model, for each will vary in meaning and function across cultures. Rural Colombians and the Lese both model their world on the house, but they use very different metaphors and images.

As we saw in chapter 3, the Lese house is the chief component of Lese life and thought. Built upon metaphors of the body and gender, the house becomes the center of relations of inequality between men and women, children and adults, Lese and Efe. As we also saw in the previous chapter, the relations between men and women are modeled upon the actual structure of the house (in which sticks support mud as men support women), and Lese-Efe relations are, in turn, modeled upon gender relations (in which the Efe, as a group, are feminized). In other words, the symbolic material out of which the Lese form an image of the Efe, and thereby a contrasting image of themselves, has its origin in perhaps their most basic social space: the home and the hearth. What could be a better source for cultural representations of inequality than that most fundamental form of domination and subordination, male-female relations?

One of the central arguments of this book is that Lese-Efe ethnicity and the forms of inequality associated with it are discernible in the Lese house. In addition to integrating the Lese and the Efe into a common function—the production, consumption, and circulation of foods—the Lese house is a means of grouping together and culturally structuring relations of ethnicity and inequality. This chapter explores two sides of the house: its symbolic representation, partly as revealed in Lese myths, and its role in the Lese-Efe economy. We will begin to see how Lese ideas about the house ramify to the production and circulation of foods and to the organization of the Lese and the Efe. In the myths, we find embodied a number of basic ideas about the house that are not explicitly brought out either in everyday discourse or in social and economic life.

The House in Mythology

Both the Lese and the Efe cosmologies include stories about an Efe ancestor, named Befe, who became an evil spirit, who still exists and continually plays tricks and carries out violent acts in Efe camps and

Lese villages. Befe is described as having the physical appearance of an Efe man, although he has a gargantuan penis several feet long. One Lese story about Befe explicitly represents the penetration of the Efe into Lese villages. The story tells of a Lese girl named Uetato who tries to find a place to sleep among her siblings, but because the house is so crowded, she has to lie down on a small area of ground inside the house. During the night, Uetato's brothers and sisters have diarrhea, in fact, so much diarrhea that it eventually chokes and kills Uetato. After she is buried, Befe comes into the village and uses his large penis to exhume her body. He first rapes Uetato's corpse and then goes on to rape each of the village houses by penetrating the doors.

Befe is especially dangerous because he comes from the forest and because he is sexually powerful. In everyday life, Lese men fear both that Lese women will be sexually attracted to the Efe and that Efe men will attempt to engage Lese women in sex. Befe is a projection of that fear, and Befe's physique and character are shaped by the Lese notion that Efe men have strong and uncontrollable desires for sex. It should have struck the reader by now that the "masculinization" of the Efe in this story stands in contradiction to the "feminization" of the Efe described in the previous chapter. As I shall elaborate later, the two characterizations are not contradictory, for just as Europeans managed their fear of Africans by infantilizing them, so do the Lese manage their fear of Efe male sexuality by feminizing them. Befe represents the Lese image of Efe sexuality in its most raw and unrevised form.

Perhaps the most important element of the story is the rape of Lese houses, for these are not only penetrable by the Efe, they are already penetrated, since the Efe are members of Lese houses. Another story, presented earlier in chapter 3, highlights the suggestion that Befe represents the incorporation of the Efe into Lese houses, and, indeed, that the Efe are essential to the formation of the Lese house. Recall that an Efe man teaches a Lese man that his wife bleeds every month not because she has a wound where there used to be genitals but because she is menstruating. The Efe man teaches the Lese about sexual differences, and, through a reversal of normative roles, produces the first Lese man: a child fathered by an Efe and mothered by a Lese. This story illustrates the bringing together of both nature and culture, sexual and cultural knowledge, as well as the establishment of the house, for all houses ideally contain a married couple with children and are defined as basic reproductive and economic units. The story also informs our analysis of the house through two reversals: in the first, the Efe man

and Lese woman engage in sexual intercourse, a reversal from everyday affairs in Lese-Efe life in which sexual intercourse between Lese women and Efe men is considered by the Lese to be a most heinous crime; the second reversal revolves around the pasa. The Lese woman lies in the pasa, yet the pasa is a meeting place for men only and is not an appropriate place for someone who is ill. Women should very rarely be in the pasa, and when they are ill they should be inside the house. Of course, there is no indication that these people lived in a house, and indeed my informants stated that the characters had not yet been given a house by God.

In the third Lese story, one that is widespread among the Lese of Malembi, relations between Lese women and Efe men are represented in a more subtle and complex fashion. The story begins with the myth of the first man, who had few human features. His body was vaguely like that of a man, but he had crops growing out of his hair folicles, and out of each of his orifices. His eyes, testicles, and heart were fruit. He could not eat, speak, defecate, or engage in sexual intercourse. As one informant put it, the first man "was a tree." But soon woman was sent by the Creator, Hara, to give man speech and human bodily functions. Once man had learned to eat and eliminate food, and had shed his treelike appearance, Hara built the man and woman a house and told them to have sexual intercourse. It is in the house that man became a complete biological and social adult. In the most complete version I heard, the myth was elaborated as follows:

Hara was his name. He was also called Bapili [Ba = already, ipili = turned upside down]; we black people also call him mungu [Swahili for God]. His son was Mutengulendu (literally, man all by himself a long time ago), also called Ngochalipilipi. Hara "put" [created] Mutengulendu, and then chased him away. Mutengulendu stayed in the forest and wandered around the forest. The girl Akireche discovered him in the forest. Hara also "put" Akireche. Hara put only girls. Her work was to dam water to get titi fish. Akireche went to the water, and she remembered something. Hara had told her, "Look for someone who is in the forest."

She said, "Today we are going to dam water farther down the stream than we usually go." When Mutengulendu heard voices he went down to the water. The day when the women went to the water, the other women said, "Today we will go really far downstream." The woman who went ahead went to find the man, and she said to her sisters, "There is a man here!" Akireche said, "This is my man, not yours." They began their return home, and Akireche said to her father, "I found a husband today." "Where?" "At this place in the forest." "Did he say anything?" "No. He had a lot of hair. There were yams and bananas and roots coming out of his

head. He is not like a person" [muto ]. This river was the Apukarumoi. The man was drinking this water. He wandered in the forest without a house. The father said, "Where did you see him?" "At this place in the forest." Hara was happy.

The name of God, it should be noted here, also means "turned upside down." Might we also expect other reversals to occur in the story? This first Lese man appears to be represented as his opposite, an Efe man. The first man is not like a muto. He is hirsute, a quality never attributed to Lese men, but which, for Lese, is a hallmark of Efe physical appearance. The story also introduces a forest/village dichotomy and gives the impression that the village area has boundaries, for it is only from a bounded area that the woman can go "farther" in search of the man. In addition, the man is said to wander in the forest, just as the Efe are said to wander in the forest, living in temporary huts and never building houses.

The story thus suggests a sexual association between Lese women and Efe men. Woman finds this man when she travels to the river. In Lese stories, women characters who go to the river go there to engage in sex or in acts specific to women, such as washing one's vagina or navel, or digging for shellfish. In a few stories, women who travel too far downstream actually lose their vagina or navel when it becomes detached from their bodies. In this origin story, woman is explicitly looking for a husband. And if we are to believe that the first man is a symbol for the Efe, the impending sexual relationship between the two people reverses the natural Lese order in which Lese women and Efe men are forbidden to engage in sexual intercourse with one another. The story continues:

Day broke. Hara gave white riga [weeds] to the girl, and said, "When you find him, cut his head hair, and when it falls down, put it in the mud, bury it in the mud. This hair will change into eji [liana cord used for constructing houses]. When you travel to the forest, you will use this to build a house." Then tell him to stick out his tongue. When he puts it out cut it down the middle. You will draw blood. Put the weeds on his tongue to stop the blood.

The Efe, of course, provide house-building materials for the Lese; they bring the liana cord and trees from the forest that the Lese use for the skeleton of the house. In this case, the integration of the first man, or shall we say, Efe, into the human world depends upon altering him severely, including cutting off his hair. Given what we know about the feminization of the Efe, it does not seem farfetched to interpret the cut-

ting of the hair as a symbolic act of castration. By cutting the hair, and presumably the crops growing out of his orifices, woman also begins to bring him into the realm of the farmer, making culture out of nature, incorporating nature into culture. The hair of the first man, like the rest of his body, is material to be cultivated (cf. Gudeman 1986:142–157 on the body as an economic metaphor). When it is planted in the mud, it grows, as the seeds of last year's harvest grow when replanted in the soil. The body is a metaphor for the composition of the world, as expressed in everyday life when Lese farmers refer to the first sprouts of their crops as "its hair." Woman is thus the farmer; she takes the forager out of the forest, away from foraging, and into village life.

The cutting of the tongue has to be seen as a sexual drama, in which the woman, having altered the first man, repeats the act of reproduction. Menstrual blood is drawn from the man but its flow is halted by the white substance. The process is identical to that found in the myths and rituals outlined in the preceding chapter, in which white substances, in the form of bark powder, or semen, stop the flow of blood and create life. Furthermore:

The girl came to find Mutengulendu and she said, "Stick out your tongue." When he stuck out his tongue she sliced it down the center, and began to cut his hair. She cut it all off and put it in the mud. She placed white riga leaves on his wound. When she put the leaves on it, she also put medicine on it, and he stopped bleeding. Right away he started to speak. Akireche returned alone to her father and said, "I cut his hair and his tongue, and he started to speak." The father said, "Go and build a gburukutu [Efe house], and then take the man inside." She went and built the house, and they came inside. Night came, and Hara gave them sleep. A lot of sleep. A machine came at night and cleared a huge area for the village, machines sent by Hara. The big village had big houses, without people, side to side, facing each other. But for all the houses there was only one pasa. They slept and slept and slept until midday. The woman woke up and said, "Open the door, night is over." When they left the house, they saw the big village, and they were surprised. The woman went to look, and so did the man. They thought there were people, but there were none. They went and saw good houses, and found a good one in which to sleep. They moved there. Night came, they went inside. They slept, and his penis would not stand up. Night came again and the penis would not stand up. The woman said, "I am going to Hara." Hara asked the girl if he urinated. "No. He vomits everything. He vomits his feces too. And his stomach is huge." Hara said, "It is good that you spoke to me. Go back. Return."

At this point, the first man is about to realize full adulthood in the Lese house. He has been removed from the forest and has made the

transition from living without a house, to living in an Efe hut, to living in a Lese house. Those with psychoanalytic concerns will be interested to note that his changes parallel the developmental phases outlined by Freud, from the oral, to the anal, to the phallic. From here:

Akireche returned, and Hara came to the periphery of the village to break mabondo [cut down a palm wine tree]. They all asked, "Who's cutting something?" He told her, "I am going to look." Mutengulendu arrived at the place. "Hey friend! Banai! Wait! Let us drink!" When he drank he began to vomit. Hara asked, "Why are you vomiting?" "My stomach does not like a lot of things inside of it." So Mutengulendu said, "I am returning." Hara said, "Come in the morning!" Hara returned as well. In the morning Hara arrived. Ngochalipilipi said, "My friend came." The woman said, "He is not your friend, he is your father." "No!" Ngochalipilipi said, "He is my friend, not my father."

The confusion over how the first man should address his father parallels the confusion over how Lese and Efe men should speak to each other. Most partners call each other either "my Efe" and "my Lese" or ungbatu , which means "partner" and is used exclusively to refer to the relationship between Lese and Efe partners. Often, however, kin terms are used because the Lese and the Efe adopt their partner's kinship universes as their own. The kin terms they choose to employ have connotations of both equality and inequality. For example, partners will address and refer to one another with the term imamungu , meaning "sibling" or "my mother's child." Imamungu indicates friendship and equality. The same is true of banai , as used in this story, a form of address that literally means "friend." Inequality also has its terms. Efe men may express their subordination to their partners by calling them afa , meaning "my father," and Lese men can refer to their Efe partners as maia ugu , meaning "my child." The difficulty of finding terms of address, as expressed in the myth, arises out of the contradiction between the dual idealized relations between the Lese and the Efe: inequality, on the one hand, intimacy and loyalty, on the other. Every Lese and Efe partner has to face the confusion of how to conceive of the other in terms of equality and inequality. Hara, as the one who brings Ngochalipilipi into the village and gives him a house, is no exception. Next, we see that Hara successfully completes the transformation of the first man, and, at long last, Lese society begins:

He came and found Hara and he saw that Hara had placed a board across a large gorge at the river. He became afraid. Hara said, "Climb up." "No. I will fall." Ngochalipilipi climbed up, and when he got to the center, Hara

said, "Now stop, and lie down." "I can't!" He lay down. "Turn your buttocks so it faces downstream." Hara came, cut an anus in Nogochalipilipi's buttocks, and feces came shooting out. Everything came out. Hara took the riga and placed them on the anus, and the sore healed. Hara told him to descend. One thing was left. He gave him palm wine, and he drank, and he gave more, and he drank more. He wanted to urinate. Hara said "take this riga and place them on your penis." He urinated right away. They returned to the homestead. In the morning she went to Hara and he asked her, "How did you sleep?" "His body has not moved mine, and his penis will not stand up." Hara told her to sleep naked. That night she slept naked. It was futile. Hara told the woman to tell her man to come to him. In the morning he went to Hara, and received medicine to place on his penis in case he wanted to urinate. When he returned, and he wanted to urinate, he placed the medicine on his penis, and urinated. The father said, "Give this medicine to your woman when you arrive at the homestead." When the woman took it she put it under her [in her vagina] for a moment, took it off, and put it in Mutengulendu's hand. Right away a fetus appeared there, and she had it many months, and gave birth to a boy.

Other stories concerning the origin of Lese people or clans do not include the Efe as central characters, but the plots are nonetheless linked to Lese-Efe relations. With only a few exceptions, these stories relate incidents of social fragmentation in which the Lese of a single clan split into smaller clans, which then split into smaller villages that may contain as few as one or two houses. According to my informants, the original clan in history was, like all clans, a single village, and this village constituted the whole of the Lese people. When I asked how many houses were contained in this immense village, my informants gave different answers. Some said that the Lese all lived in one giant house linked to a single pasa, and others said that they all lived in separate houses, but that they shared a single pasa. The disagreement is irrelevant, however, because the pasa is the symbol of the house, and since no house is complete without a pasa, the myths tell us that the Lese consider their ancestors to have been members of one house.

It is to more concrete concerns that I now turn, to examine the role of the house in political organization, and to address the question of how the house informs aspects of Lese everyday life not informed by the lineage or descent. The house and the actual terms of the economy provide the cultural foundation for the Lese-Efe partnerships and for the mythology just presented. Together each of these aspects of Lese society and culture will demonstrate that the Lese and Efe economy is a cultural economy right from the start, culturally modeled and represented. The economy is not founded on a command of resources or of

the power of one group to dictate economic knowledge or practice. Yes, there is a group that has more power than the other, but neither group inhibits the economic practices of the other. Before proceeding to the cultural model of the economy, we shall consider the Lese in light of some specific observations made by other anthropologists in central Africa.

Isolation and Political Organization in Anthropological Reports

One of the more striking characteristics of Lese village life is the absence of collective activities. Rather than encourage group activities, Lese society makes a distinct effort to isolate groups from one another. The smallest social unit is the house (ai ). In the Lese language, those social units more inclusive than the house are identified by one word, gili . Gili is a relative term of reference, and whether it refers to the clan or to the ethnic group is determined by context. Gili is an oppositional term with variations in meaning that are due, as Evans-Pritchard put it in the context of the overarching Nuer term cieng , not to "inconsistencies of language, but to the relativity of the group-values to which it refers" (1940:136). Gili , when appropriated, implies specific degrees of structural distance. Yet, for analytic purposes it is important to note that each of the social units considered gili has a definite empirical status. These units may be classified into the phratry (political alliances of intermarrying clans), the clan and the village (groups of people who may or not be genealogically related, although they believe they are descended from an unknown common ancestor), and the ethnic group (Lese or Efe).[1] According to my informants, the Lese have always wanted their population, phratries, clans, villages, and houses to remain physically distinct from all others. For both the Lese and the Efe, phratries are opposed to other phratries, both politically and spatially. Not all Lese settlements are arranged in the same pattern, but an attempt is usually made to place clans next to other clans of the same phratry, with a greater distance maintained between phratries than between the clans of the same phratry. Before resettlement at the roadside, clans of the same phratry were usually located as much as several kilometers

[1] The Greek phratria , or clan, was in fact a subdivision of the phyle , or tribe, but in anthropological literature phratry has come to represent a collection of clans allied by marriage, and I use it in that sense out of convention.

from one another, and some phratries were located as far as a day's walk from one another.

Lese, the elders say, should live apart from non-Lese, and members of different Lese phratries should meet rarely, and then only for war or marriage. Even members of different clans, though they should meet occasionally to drink palm wine, should live apart. (Some younger men told me that for the sake of the Republic, the Lese should live together with members of other ethnic groups, like the Azande or Mangbetu, but these same men also expressed fear that in a village with Lese of different clans and phratries life would be marked by violence and death.) On the next level, too—that of houses—the ideal is privacy, not communality: the members of different houses should neither cultivate, circulate, nor eat foods with one another. It is all right for meat to be shared between members of the same village, and sometimes between members of different villages, but cultivated foods should not be shared with other houses. The distribution of cultivated foods creates inequalities between givers and receivers, and all the Lese living in a given village should be socially and economically equal to one another. It is common, of course, and permissible, for the Lese to give cultivated foods to the Efe, because the Lese and the Efe are not intended to be equals.

Nearly every ethnographer and explorer to encounter the Lese, Efe, or other farmers and foragers of the Ituri has remarked that the farmer inhabitants tended to interact rarely with other ethnic groups (with the exception of the various Pygmy groups), and that they had no extensive political organization but sought to separate, rather than link, various social units from one another. Jan Vansina, for example, notes that southern central Sudanic culture, and Proto-Mamvu and Proto-Ubangian societies in particular, maintained house-centered political traditions. He points out that although marriage, ritual, and age grades among Proto-Mamvu societies established intervillage linkages, "the original southern central Sudanic culture had been one of herders and farmers living in dispersed settlements, where each household lived by itself without territorial leadership beyond the household. . . . There was therefore very little organization in Proto-Mamvu society beyond the extended household. There were Houses but no villages, no districts, and no big men" (1990a:171).[2]

[2] In my own usage, I do not capitalize the word "house." However, when citing or discussing Vansina, who capitalizes the word, I shall respect his usage.

Paul Joset (1949), Helena Geluwe (1957), Edward Winter (n.d.), and Colin Turnbull (1983a), all of whom have conducted research on Ituri forest societies, have each commented on the tendency for villages to fragment into insular households, and on the infrequency of social and economic relations between houses, villages, and groups of villages. In his "Notes Ethnographique sur la Sous-Tribu des Walese-Abfunkotu," Joset describes the way in which villages feuded with one another, and houses feuded with houses, and how the feuds strengthened the internal stability of each of these social units and separated them further.

The Lese offer to our eyes a model of the tribal family, each community composed only, in effect, of one family, in the extended sense. Scattered throughout the immensity of the forest, living by themselves, without significant relations with others, engaged in chronic wars, these communities gave to their members an independent spirit which, having been conserved nearly intact, inhibited the unification of political organization. (1949:5, my translation)

Of the Bila farmers with whom the Mbuti Pygmies live, Colin Turnbull (1983a: 62) wrote:

A few villages offered a warm and friendly welcome to visitors, though even there, and even in the smallest of villages, there would always be some who voiced suspicions that the visitor was in truth some malevolent force seeking to destroy the village. And against all those who passed through, on foot or by car or truck, most houses had medicine hanging from the eaves to ward off the evil carried by "others," even kin from a nearby village.

The larger villages, consisting perhaps of thirty or so houses, showed the same manifestation of suspicion and concern with supernatural forces within themselves. Families, lineages, and clans clustered together in clearly recognizable units, each with its own meeting place, or baraza [the Swahili term for pasa], each with its own protective medicine. And as often as not, a single house could be found isolated on the outskirts of the village, or, sometimes, boldly established in its own special space right in the middle of the village. In the latter case it was most likely a blacksmith, always associated with the power to manipulate supernatural forces. Those isolated on the edges of a village were generally considered witches or sorcerers, though in the first instance they may actually have chosen to build their house there because they had no close kin or friends in that village. Even that in itself would be suspect, as would any preference for privacy.

Just as each tribe considered neighboring tribes to be masters of the craft of evil, accusing them of all manner of barbarity, including cannibalism, so each village suspected the next, and each household its neighbor.

As much as I am inclined to distinguish myself from these kinds of generalizations, one point became clear to me as my fieldwork pro-

ceeded: that many Lese, young and old, want to be disconnected, inaccessible, and remote, and that they want these separations to demarcate a variety of different levels of society. One way the Lese conceptualize their social organization is in terms of membership—in the house, the clan, and the phratry. As will become clear later on in this chapter, with the exception of the house, the members of each of these social units wish to have as little to do with one another as possible. Phratries oppose one another, as do villages and houses. Ideas about malevolence (a subject I shall take up in chapter 5), conspicuous in Turnbull's and Winter's work, are one expression of this opposition.

The Amba

The absence of indigenous political organization raises the question of whether a descent or corporate model is applicable to the ethnographic description of the farmers of the Ituri. Fortunately, we have an account, Winter's Bwamba. A Structural-Functional Analysis of a Patrilineal Society , which seeks to fit the Amba of the eastern Ituri in a structural-functional and corporate model. Because of numerous similarities between the two groups, Winter's work on the Amba is especially useful for analysis of isolation and the role of the house in Lese society. Amba witchcraft beliefs, marriage patterns, family structure, domestic economy, and even much of their language, in many ways resemble those of the Lese of Malembi. Winter and I studied very similar societies but we saw very different things. My criticism of Winter is that his structural-functional blinders led him to emphasize clans and egalitarianism among the Amba and to de-emphasize, even ignore, the relations between the Amba and the Pygmies with whom they lived.

"Amba" is, in fact, a large category that includes a group of people who call themselves the Lese-Mvuba. The Amba live in a section of the Ituri that, at the time of Winter's research, was the eastern border of the Belgian Congo, and today extends into western Uganda. Winter (n.d.:137) uses the term Amba to encompass a variety of linguistic groups: the Buli Buli; the Bwezi, who speak Bantu languages, and the Lese-Mvuba, who speak a Sudanic language. Importantly, the Amba maintain relations with Pygmy groups who speak the language of the Buli Buli. Though Winter pays little attention to the Pygmies, his oversight, which perhaps was due to his theoretical concerns, will inform our larger argument that a corporate model does not apply to the Amba and does not take into account interethnic relations.

Winter fits his data neatly within a structural-functional model of corporate descent groups and minimal and maximal lineages, and describes the Amba as having corporate groups. He defines the corporate group according to A. R. Radcliffe-Brown's criteria: (1) adult male members come together for collective action, (2) there are group representatives such as chiefs, and (3) groups such as a clan or lineage possess or control property collectively. Winter concludes that the lineage system based on patrilineal principles of descent organizes all of Amba life.

It is undoubtedly true that the Amba organize much of their life around descent. However, given the criteria appropriated from Radcliffe-Brown, there is little evidence to suggest that the Amba have corporate groups. While the Amba reckon descent, as do people everywhere, there are few forms of collective action among descent groups. Winter discusses the "blood feud" as a form of collective action, but he presents few data to support the contention that blood feuds exist, or existed at a historical period before his fieldwork. The only evidence he cites of a blood feud is a story (apparently told to him) about a woman who murders her husband and is then beaten by the husband's brothers (n.d.:110). Regarding the subject of authority, Winter states that, "at most, a person may excercise authority over a group composed of himself, his own children, his brothers and their children," that there is no authority above the level of the village (n.d.:102). Elders exert influence, but they do not form a separate body within the community.

Usufructuary rights to land are limited to those who live in villages situated adjacent to the land, but these rights last only as long as the village (about seven years). Winter notes that land is so plentiful there is a "lack of interest in land" on the part of the Amba (n.d.:107). Rights to land are inherited solely from father to son, as is any other wealth. If there are no children, the land may be claimed by anyone, regardless of connection with the deceased's minimal or maximal lineages. Witchcraft beliefs pit houses, rather than clans or lineages, against one another so that there is considerable fission and very little fusion of clan members. In fact, farming is carried out at the level of the house:

The village does not function as a unit of production. As will be seen . . . agricultural production is carried out almost entirely within the immediate family. Even the polygynous family breaks down into its component parts for this purpose. There are no village working parties. In fact, each man and his wife carry out their agricultural activities by themselves (n.d.:85).

Winter goes on to note that consumption of cultivated foods and meat is also limited to the house. And beyond the level of the village, which

ideally consists of single clans, and which is identified by a single clan name, Winter finds no overarching sets of political alliances: the area occupied by the Amba is simply "a series of villages," the "villages are completely independent of one another," and "the village is the largest corporate group to be found in the traditional system" (n.d.:85).

For the Lese, as for the Amba, I would suggest that collective action is rare; nor is there much evidence to suggest the existence of corporate groups. Each village represents a single clan and contains from as few as two to as many as sixty residents. The Lese have no indigenous authority position beyond ritual elder of the village, and inheritance of property does not usually occur. When a man dies, his house is usually destroyed along with his property, and land is not inheritable. It is true, however, that clans, rather than lineages, are vital to Lese social life. Social identity and organization are reckoned according to clan membership, as are preferred and prohibited marriage alliances, and clans unite against other clans in cases of dispute, illness, and warfare. The Lese do not have groups we can easily define as lineages, nor do the Lese use lineal descent to organize social or ritual practices.[3] There is little evidence to suggest that either the Lese or the Amba make sense of their world by applying a corporate model, in Radcliffe-Brown's sense, and there is much evidence to suggest that a more central organizing model is the house.

Yet no author, including Turnbull, has related this political organization, or lack of it, to the partnerships between farmers and Pygmies. Winter notes that the Amba and the Pygmies "have always lived in the closest association with each other" (n.d.:8); the Pygmies are made fictive kin of the Amba, and there is a forager-farmer relationship in which the Pygmies give meat to the Amba in return for cultivated foods and iron. But Winter takes his analysis no further—perhaps, in part, owing to his (and Turnbull's) concern with illustrating egalitarianism and solidarity. At the level of the clan, everyone is idealized to be alike, even interchangeable; the clan is conceived of as a group of adult males, and so there is a great sense of likeness among its members. Clans unite in opposition to other clans and can mobilize for collective action in the case of dispute or illness. Inequality is shunned at the level of the clan;

[3] W. D. Hammond-Tooke (1985) makes a similar point about the Cape Nguni in South Africa: "In fact, the important descent groups among the Cape Nguni would appear to be clans, rather than lineages. It is the common possession of the same clan name which gives certainty of common origin and place in the social structure. It is by virtue of clan membership that exogamic rules are defined and the (clan) ancestors invoked on the occasion of a ritual feast, despite the fact that the clan is widely dispersed and its members never come together as a clan. Thus the 'transformation' in descent group theory from clan theory to lineage theory (Kuper 1982) has been a retrograde step for Cape Nguni studies" (p. 90).

at one funeral, a Lese man proclaimed, "We are all Andisopi clan, we are all Zairians, we are all black people, we are all dying." At the same funeral a group of women shouted out, "On this day we are all the Andisopi clan, there are no foreigners here, we are all of one clan; on this day, we all have penises, we are one clan, one large clan." The clan, then, mutes relationships of difference, whether ethnic or gender.

Mangbetu-Meje Houses of Northeastern Zaire

There is an important distinction that must be made between the Lese clans/villages and houses and those of other societies in the Ituri. In Jan Vansina's historical construction, the villages in the Mangbetu and Budu region, near the Lese, consisted of a single house (Vansina 1990a: 172; 1990b: 78). He states that "Village communities were thought of as a single family whose father was the village headman, and the big men of each House were his brothers. The village was thus perceived as a House on a higher level" (1990a: 81). The Lese house, in contrast, is not a figuration of village or clan relations (the village being synonymous with the clan) but the model of a particular set of social processes that are not modeled by the clan.

Vansina's work on kinship organization is especially relevant to this study of interethnic institutions, however, because he suggests that different ethnic groups and clusters within the rain forest share a common tradition and are the product of complex interethnic interactions. Vansina argues that by the eighteenth century there were several different types of social organization related to the different historical traditions of three immigrant groups: the Ubangian ancestors of the Azande and Mayogo, the ancestors of Bantu speakers, and the Eastern Central Sudanic speakers—the ancestors of the Mamvu, Lese, and Mangbetu. The Ubangians did not maintain a strong political organization with chiefs, headmen, or war leaders, and their settlements were temporary and dispersed (Vansina 1990b:76). The Bantu speakers maintained three distinct levels of social organization: the House, the village, and the district. The Bantu House, in this case, was essentially an extended household that could incorporate members of a number of different lineages. Finally, the Mangbetu had a flexible and dispersed social orga-

nization (Vansina 1990b:77) with little leadership above the extended household. As these loosely organized groups met, they mixed their customs and social organizations, and they developed a common House-centered organization that provided the cohesion and hierarchy that had been absent from any one of these groups. The interethnic mixing about which Vansina writes echoes Evans-Pritchard's earlier historical account of the very complex ethnic composition of Zande society (1971:22–43). Precisely because the house is the locus of interethnic integration, it is a dynamic and historical social institution.

The similarities and differences between Mangbetu-Meje and Lese houses also help us understand the structuring of Lese houses. In contrast to the Lese house, the Mangbetu-Meje house, in the early colonial period, was structured around a core of members of a patrilineage (Schildkrout and Keim 1990:89). Whereas Lese houses resemble nuclear families with the addition of the Efe, Mangbetu-Meje houses could contain from one hundred to two thousand members. Although, like the Lese house, the Mangbetu-Meje house was not constituted by the clan or lineage, it often included as its members many nonlineage and nonclan individuals: in the Mangbetu-Meje case, this included wives, sisters, sisters' children for whom childwealth or bridewealth payments had not been made, slaves, and clients.

Despite these profound differences between the houses, it would seem that there are some fundamental similarities in the principles underlying Mangbetu-Meje and Lese houses: namely, the structuring of the house illustrates two complementary but opposing models. Schildkrout and Keim write: "Overall leadership of the Mangbetu-Meje House was determined according to two sets of principles. One set reflected the ideals of the lineage; the other attitudes towards the individual" (1990:89). In addition, paraphrasing Vansina, the authors describe contrasting ideologies: "The first set posited unequal categories of House membership such as elder-younger, patron-client, master-slave, male-female, and controlling lineage-junior lineage. . . . The second set assumed equality between the members of the dominant lineage and allowed the lineage to choose the most capable leader" (1990:90). For the Lese, in contrast, I have stressed that activities and leadership are not organized according to lineages or corporate groups, although clans are important for structuring marriage alliances, the building and settlement of villages, and warfare. I have also differentiated the Lese houses from those of these other societies by emphasizing that the house and extended kinship organization as villages and clans do not model

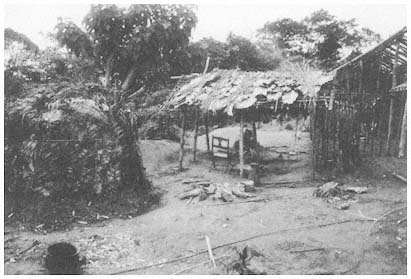

Before completing his house (right) a Lese man's Efe wife builds them a

makeshift Efe hut. The Lese man has also built a pasa (center).

Photograph by R. R. Grinker .

one another. Yet, the Mangbetu-Meje houses illustrate a pervasive social organizational concern in this region of Africa with managing coexisting principles of equality and inequality. The Lese oppose these two principles not within the house but between the house and the clan.

Inequality and the House

As a Lese proverb puts it, in the clan "leopards give birth to leopards" while in the house "we know each other not by our spots but by our noses." In other words, clan members are identical, but house members know one another by living cheek by jowl, by knowing one another's differences. The village is the level of approved similarity and equality, whereas the house is the level of approved difference and inequality. At the level of the "house," in contrast to that of the "clan," the Lese find inequalities in status and access to resources to be the normal state of affairs. The house is characterized by dependence, and by the relations of inequality engendered in dependency. These relations characterize the links between the Lese and the Efe and are made at the level of the house—the meeting place of birth, marriage, death, social inequality, and ethnicity.

Marriage and Lese-Efe partnerships are two sets of unequal relationships that are integrated at the house. These two unions are, in fact, the basic constituents of the Lese house. In the preceding chapter, I noted that the terminology used to describe and define the marriage of a man and woman, and the formation of a Lese-Efe partnership, are the same. Adult men are expected to maintain both of these unions in their new houses, and to serve as the protectors of the house members. Indeed, an adult man is himself like a house because he encompasses and protects the members. A central metaphor is "the house is a body." One informant said: "[The] house [ai ] is our shelter. We depend [ogbi ] on the bones [iku ] of our house. If you do not have a house, people will think you are not a man, that you have no family [famili ]. My house is like the pangolin [whose scaly skin is called its ai , or house]." Houses, in short, are vital to the integration of difference. Within the house, the Lese and the Efe, men and women, are simultaneously differentiated and unified. To quote Dumont in a different ethnographic context (1970:191): "In the hierarchical scheme a group's acknowledged differentness whereby it is contrasted with other groups becomes the very principle whereby it is integrated into society." Difference is itself constitutive of integration.

The emphasis on equality between houses, and inequality within houses, is illustrated by the restriction on the movement of cultivated foods between Lese houses and the distribution of cultivated foods to wives and Efe. Giving cultivated foods symbolizes the dependence and subordination of the receiver to the giver. Many Lese say that to give cassava or peanuts or potatoes to another Lese is tantamount to calling the receiver an Efe. Only the Efe, it is said, should ogbi —that is, lean on, rest upon, depend on—another Lese, as the Lese say the Efe depend upon them for cultivated foods. Since every Lese man and woman expects that he or she will be the equal of the other men and women in their village, it is not socially acceptable, in terms of equality, for the members of one house to be deficient and to request or need goods that they should have already. For this reason, the Lese rarely trade or share cultivated foods with the Lese of other houses. In fact, some of my informants defined the house explicitly as the unit within which production, consumption, and the sharing of cultivated foods occur. No one but a house member should produce or eat the foods that come from that house. Likewise, only house members can eat within the house. One informant said, "My house is where I eat, and no one else eats there. Even if I ask someone to eat there he won't, because he will

think I am trying to poison him, or raise myself over him [brag, iba-ni ]. The house is where a baby drinks his mother's milk and grows."

Conceptions of the Lese-Efe Economy

If the house mediates Lese relations of inequality, then we must seek its symbolic representation not only at the level of ideas and concepts but also in specific domains of social life, including the economy. Despite the range of Lese-Efe relations, the Lese and the Efe describe those relations as of the most impersonal and contractual nature. For example, both groups define their separate group identities as a matter of a strict division of labor between farming and hunting—an economic arrangement that is mutually beneficial: the farmers give cultivated foods and iron in return for the forager's meat and honey. The division of labor, along with the trade of goods that the Lese and the Efe say results from that division, is a central ethnic marker distinguishing the two groups, even though the farmers frequently hunt and gather, and most foragers know how to cultivate gardens (but rarely do so). The Lese accept the kinds of interactions discussed above, from child rearing to ritual to warfare, as more or less an associated, if not very important, part of the economy; the interactions are residual to the distribution of material goods, mere by-products of a meat-for-produce transaction. Members of both groups give the same definition: that they give things and get things; they act collectively, and the acts are embedded in economic relations. Together the Lese and the Efe give the impression that their relationship is founded on the giving and receiving of such items between groups.

For both groups, meat is by far the most highly valued good circulated. Some of my Lese informants say that the only reason that they live with the Efe at all is to obtain meat—and they even say that they are afraid to alienate the Efe because this might threaten the supply of meat. But the truth is that the Lese obtain most of their meat by themselves or from other Lese. Moreover, although the Efe provide much of the labor needed to cultivate the Lese gardens, my informants rarely mention the procurement of Efe labor as a defining characteristic of the partnership. Despite the Lese's silence on this aspect of the relationship, labor, as we shall see, is a vital part of the Lese-Efe relationship. The distribution of Efe meat to Lese partners symbolizes the participation of the Efe in the production and distribution of Lese cultivated foods. Labor aside, the Lese do not cite any of the other aspects of Lese-Efe

interactions as central components of their partnerships. Efe also help raise Lese children, are the main participants in Lese rituals, and, among numerous other things, serve as guards and protectors, but the Lese whom I interviewed treated these aspects as secondary to the giving of meat for cultivated foods. It appears that the intimate relations that constitute everyday practice between Lese and Efe are dissociated from the ideology of practice. This seems to me an anomaly quite at variance with what is commonly said about the "gift economy" (Bourdieu 1977:172), that the "good faith" economy is costly because societies spend so much time and effort developing concepts of kinship, marriage, reciprocity, and so on, to disguise self-interested and economic acts. The Lese and the Efe do just the opposite. They frame interpersonal interactions with one another in an idiom of economy. "Forager" and "farmer" thus become encompassing ethnic categories.

However, despite the fact that the two groups generally speak of their relationships in a way that sounds very much like trade and material exchange, the actual words they use to describe the circulation of goods say something very different: the vocabulary used tells us that the Lese and the Efe are not involved in a trade at all, but rather in a "division" of shared goods to those who hold rights in them. The vocabulary used and the ideology articulated are indeed contradictory.

The "Distribution" or "Division" of Foods

The Lese use three general concepts to describe the transfer of material goods between people: division (oki ), purchase (oka ), and exchange (iregi ). The verb oki , meaning, "to share," "to divide," "to give," refers primarily to transfers of goods for which reciprocity is generalized rather than direct or balanced. My informants translated the term oki into Swahili as -gawa (to divide), rather than as the more common Swahili term for the circulation of goods, -leta (to give, in KiNgwana; to bring in, in KiSwahili). This is because those things circulated are transferred between people who already have rights in them. For example, when a man offers his baby a piece of cassava to eat, he considers this a "division" of his foods, since all young children have a claim on the goods their parents produce. Oki denotes apportioning, distribution, and the possession of parts of a common good.

From here on, I shall thus translate oki as "distribution." Division might suffice, but it can imply an even or equal splitting up of goods which does not exist between the Lese and the Efe. Nor does "general-

ized reciprocity" capture the fact that access to goods is often unequal. The house merges the efforts of both Lese and Efe participation in the economy, but the individual does not necessarily get back what he/she puts in. Like a government that decides budget allocations, distribution is not always equal. Given that both the Lese and the Efe contribute to the foods of the house, redistribution might also be used, but redistribution implies that there is a single center from which all goods flow. Distribution has the advantage of implying a moral right, since distribution refers to the apportionment of goods held in common, as well as the potential for unequal apportionment.

The Lese and the Efe also consider the transfer of goods between trading partners to represent oki , or distribution, rather than purchase or exchange. Thus the Lese use the term oka , "to purchase," to express the transfer of goods between nonrelated Lese or between Lese and Efe who are not trading partners. When a Lese house gives cassava to a nonpartner, the Lese family views this transfer as a purchase of labor or some other form of reciprocity. Finally, for exchange (the term by which anthropologists have conventionally represented the relationship between the foragers and the farmers of central Africa), the Lese use the word iregi , which literally means "to turn around, to make into a circle." The Lese use this term only when speaking of the balanced exchange of identical or comparable items (swapping), such as when someone changes money from larger to smaller denominations or trades one knife for another. In short, the Lese-Efe relationship is founded not on exchange or purchase but rather on the distribution of common and shared goods.

The house is the single domain within which there are shared rights of access and consumption of cultivated foods. It is, in fact, the productive unit of the economy. Each Lese husband and wife cultivates a single garden together, usually with the help of their Efe partners. In polygynous houses, the two (or more) wives ideally plant separate gardens, but during very rainy seasons, when it is difficult to burn felled trees, they may work together in one garden belonging to their husband. When the wives are able to cultivate separate gardens, there is little food sharing between them. They will feed their children almost exclusively with the food produced in their own garden. If they cultivate a common garden, each wife will claim a portion of the garden as her own—as if there were separate gardens—and feed herself and her children with the food grown in that portion. But all the while, the Efe are present, in the Lese farmer's mind if not physically at hand, as participants in the garden. Even when Efe do not participate in the clearing

and harvesting of the gardens, they maintain rights to the crops grown there. And so it is safe to say that no Lese farmer plants a garden without the expectation that some of his produce will be distributed to the Efe. Lese men and women, and the Efe, depend upon the gardens for their subsistence.