PART V—

CIVIL WAR

29—

The King's Standard Unfurled

When Charles turned at last from the coast he made his way to his wife's palace at Greenwich and sent for his eldest son. Parliament wanted to separate them but Charles was firm, not only through affection but because he knew the political value of the Prince of Wales. Two issues were on his mind: the Bishops' Exclusion Bill and the Militia Bill. He had agreed on February 13, as a matter of policy, to the exclusion of bishops from the House of Lords but took his stand on the immediately vital question of the militia. His wife was safe and, as he said to Hyde, 'now that I have gotten Charles, I care not what answer I send them', and he refused to surrender his power of granting commissions for the raising of troops. At the same time there was a necessity, if help was to be received from the Continent, of securing a seaport. Hull, Newcastle, Berwick appealed to him since in the North he was more likely to win support than nearer London, but he also had his eye on Portsmouth. Before he left Greenwich he commanded that his bust by Bernini should be brought in from the garden where it stood. As it was being carried towards the house, face upward, a bird dunged upon it and the stain, according to the servants, turned the colour of blood and could not be erased.

Charles's refusal to pass the Militia Bill and his journey northward, which he began on March 3, alarmed Parliament. On the same day, using the procedure they had learned while Charles was in Scotland, they converted the Militia Bill into an Ordinance, enforceable by contempt proceedings, which put the militia into the hands of Lords Lieutenants, whom they appointed themselves. Four days later Charles was at Newmarket where a Parliamentary deputation reached him seeking for a compromise. They carried with them a Declaration of Both Houses which expressed their fears and asked for the King's return to London. Alterations in religion had been schemed by those

in greatest authority about him, the document claimed, the wars with Scotland as well as the Irish rebellion having been fomented to this end. The document hardly breathed the spirit of compromise and Charles was aghast at what he termed the 'strange and unexpected' nature of the charges against him. 'God in his good time,' he exclaimed with passion, would 'discover the secrets and Bottoms of all Plots and Treasons: and then I shall stand right in the Eyes of my People.'

'What would you have?', he demanded, as he had done so many times before. 'Have I violated your laws? Have I denied to pass any Bill for the Ease and Security of my Subjects?'

When Holland murmured 'the militia' Charles retorted 'That was no Bill!' and when Pembroke begged him to grant the militia for a limited period, Charles exclaimed, 'My God!, Not for an hour!'. 'You have asked that of me', he added, 'was never asked of any King.'

When Pembroke pressed the point, saying that the King's intention was unclear, Charles rounded upon him in anger. 'I would whip a boy in Westminster school', he exclaimed, 'who could not tell that by my answers!'[1]

Two days later he gave practical shape to his intentions by the issue of Commissions of Array which directed the trained bands to place themselves at his disposal. Henceforth Militia Ordinance and Commission of Array stood in opposition, calling upon people to take their choice between Parliament and King.

On March 15 another step was taken on the road to war when Parliament instructed Northumberland to yield the command of the fleet to the Puritan Earl of Warwick. Northumberland was a weak, possibly a sick man; he had Puritan leanings and Charles had not taken sufficient care to support the interests of his family in matters of Court promotion. He made no protest. Parliament predictably took no notice of Charles's order that Pennington should succeed to the command, Pennington himself was not strong enough to make a stand. Charles was reaping the reward, perhaps, of the little care which, inexplicably, he had expended upon the men who manned his ships. The rotting food, the unpaid wages, the lack of medical care, the squandered lives at Cadiz and Rhé rose up against him, and his carefully nurtured navy, his lovingly launched ships, passed to Parliament without a blow at the beginning of the conflict.

Charles continued his journey northward without haste and with little visible emotion. He stopped at Cambridge, where he visited

Trinity College and St John's, and he called once more at Little Gidding whose tranquil atmosphere broke through his defences: 'Pray, pray for my speedy and safe return', he begged on parting. When he reached York on March 19 one of his first actions was to send for his second son, James, Duke of York, who had been left at Richmond under the care of the Marquis of Hertford. Parliament made no attempt to hinder the boy's journey and in his delight at the reunion Charles created him a Knight of the Garter, as well as providing him with a guard of honour and setting off a blaze of welcoming fireworks.

Shortly afterwards James was called to duty. Hull had become Charles's immediate objective, for in this city were stored the arms left from the Scottish wars. Yet the attitude of the Governor, Sir John Hotham, who had been imprisoned by Charles in 1627 for refusing to collect a forced loan, was uncertain. Charles therefore sent the boy with his cousin, the Elector Palatine, on an ostensibly social visit to Hull which was intended to sound the feelings of the inhabitants. The young men reported on the loyalty of the city and next day, April 23, Charles advanced to request admission. To his dismay Hotham, who had been appointed by Parliament as a good Commons man, refused him entry. Charles proclaimed him a traitor and withdrew, though it is likely enough that the citizens would have followed the King against their Governor if they had been given a chance. More satisfactory was the ease with which the Yorkshire gentry provided him with a personal bodyguard, which he entrusted to the leadership of the Prince of Wales.

He was being joined now by many of the big northern landowners and their followers, including the Earl of Newcastle, Governor to the Prince of Wales, the Stanleys of Lancashire, and Lord Lindsey, the robust veteran of the Spanish Main and the Low Countries. Friends were also coming in from London and from Parliament itself. Edward Hyde, who had already shown himself a valuable counsellor, now felt he could serve the King at Westminster no longer and turned his back irrevocably upon the Parliament, bringing with him his friends Lord Falkland and Sir John Culpepper, both of whom had been appointed to the Privy Council at the beginning of 1642 in one of Charles's attempts at compromise. Falkland, in particular, was deeply distressed and undecided, yet was forced to the King's side on the religious issue.

At the beginning of June, Lord Keeper Littleton, somewhat timidly, fled to York bringing with him the Great Seal; by the middle

of the month the King's companions included Secretary Nicholas, Lord Chief Justice Bankes, and some thirty-five Peers including Salisbury, Bristol, Richmond, Bath, and Dorset, and he was holding court in York in a manner which would have delighted his wife. That he was able to do so was due to the magnificent generosity of the Earl of Worcester and his son, Lord Herbert. Charles had left Greenwich with virtually no money and no means of raising any but, as he made his way northward, Herbert contrived to secure £22,000 of the family assets which he presented to the amazed and grateful King. By July no less than a further £100,000 had been raised for their sovereign by this practical and loyal family. It was through their generosity that Charles was enabled to start recruiting as well as to live in a manner not too far removed from his normal style.

For a few months after he left London Charles was prepared to be conciliatory — at first until he knew his wife was safe and his sons were with him — and later under the moderating influence of Hyde, Falkland and Culpepper. He even agreed in early March to speak fair words concerning the five Members: 'if the breach of Privilege had been greater than hath beene ever before offered', he was persuaded to say, 'our acknowledgement and retraction hath beene greater than ever King hath given.' The King's studied moderation and Parliament's mistakes had their reward in the steady building up of a King's party. On April 29 a great concourse of people met at Blackheath to support a petition drawn up by the men of Kent and to select 280 of their number to carry it to Westminster. It was mainly concerned with religion, asking for the execution of laws against Catholics, the retention of Episcopacy, the protection of the liturgy against profanation by sectaries, and an end to the 'scandal of schismatical and seditious sermons and pamphlets'. It exactly conformed with the King's own position and Parliament's reaction was foolishly, if predictably, harsh. It sent for four of the signatories as 'offenders', imprisoned two of them and voted the petition 'scandalous'.

At the same time Charles was receiving many reasoned petitions, to which he gave reasoned replies, taking the opportunity of stating his case against Parliament. It is not unlikely that his advisers were taking a leaf out of Pym's book in engineering such an advantageous exchange of views and, just as the Kentish petition and its treatment by Parliament did great harm to his opponents, so this exercise undoubtedly also helped his cause. So did his reasoned answer to the Nineteen Propositions.

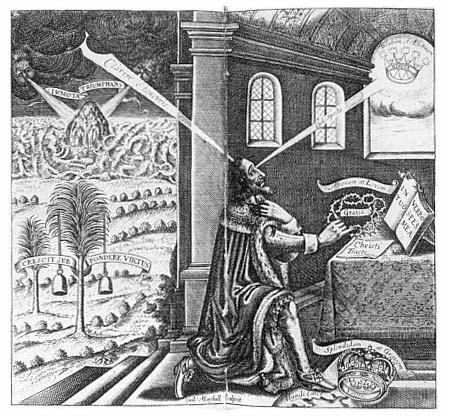

Parliament's Nineteen Propositions, the second document sent after Charles since his departure from London, reached him at York at the beginning of June. It was so patently unacceptable as to be little more than a propaganda exercise: it denied the right of the King to choose his own ministers, obliged him to accept the Militia Ordinance, to reform the Church according to the findings of a Church synod, and to place the education and marriage of his children in the hands of Parliament. Charles's first instinct was to ignore so extreme a document as being sufficiently damaging in itself to his opponents. But his advisers persuaded him otherwise and on June 8 his reply, drafted by Falkland and Culpepper, put his case with remarkable prescience.

In reaffirming his acceptance of the Triennial Act and the Act preventing the dissolution of Parliament, it confirmed his moderation; in recording his personal reactions to the Propositions it revealed the extent of Parliament's designs: if their proposals were accepted, he said,

we may be waited on bareheaded, we may have our hand kissed, the style of majesty continued to us, and the King's authority declared by both Houses of Parliament may be still the style of your commands; we may have swords and maces carried before us, and please ourself with the sight of a crown and sceptre . . . but as to true and real power, we should remain but the outside, but the picture, but the sign of a king.

The real force of the reply, however, lay in its counter-proposals. Charles did not claim a Divine Right of Kings, nor did he speak of the Prerogative. He asserted instead that the laws of the country were 'jointly made by a King, a House of Peers, and by a House of Commons chosen by the people'. In this 'regulated monarchy' government was entrusted to the King who had, consequently, the powers of choosing his advisers, of making war, and of preventing insurrection, and in whom must reside the power necessary 'to conserve the laws in their force and the subjects in their liberties and properties'. Parliament would act as a bulwark to prevent any abuse of this power, the Commons through the weapon of impeachment and the raising of supply, the Lords through their judicatory function.

By contrast, the role assigned to the monarch by the Nineteen Propositions, Charles claimed, would leave him with nothing 'but to look on', he would be unable to discharge the trust which is the end of monarchy, and there would follow a 'total subversion of the fundamental laws'. This situation would beget 'eternal factions and

dissensions', Parliament would be the recipient of such propositions as the King now had before him, until

at last the common people . . . discover . . . that all this was done by them, but not for them, and grow weary of journey work, and set up for themselves, call parity and independence liberty, devour that estate which had devoured the rest, destroy all rights and properties, all distinctions of families and merit, and by this means this splendid and excellently distinguished form of government end in a dark, equal chaos of confusion.[2]

In this enunciation of constitutional monarchy, this accurate forecast of future developments, it is difficult not to discern the fruits of discussions at Great Tew where Falkland and Hyde, Chillingworth and Hobbes had pursued just such questions of political obligation. It did Charles's cause a great deal of good, yet in offering a concept of constitutional government far beyond anything yet envisaged as practical, it was, in a sense, offering hostages to fortune.

The Nineteen Propositions and the King's Answer were part of a war of words that had been rapidly gaining momentum since the opening of Parliament. In November 1640 Henry Parker outlined from Parliament's point of view The Case of Shipmoney , in June 1641 Parliament published a collection of Speeches and Passages in Parliament , a fat book whose perusal John Lilburne gave as one of his reasons for joining Parliament at the outbreak of war. When the King published his Answer to the Nineteen Propositions , Parker replied with Observations upon the King's Answer. Various replies then came from the King's side to Parker by such men as Dudley Digges, Thomas Morton, and Sir John Spelman. Robert Greville, Lord Brooke, whose wide humanity matched that of Falkland but who believed his path lay with Parliament, wrote his splendid plea for toleration — A Discourse opening the Nature of that Episcopacie which is exercised in England — at the end of 1641, about the same time that Parker published the case against bishops in the Divine Right of Episcopacie truly Stated .

The statement of its case by either side implied justification. Parliament had greater need of justification than the King, for it was in the more unusual position of fighting an anointed monarch whose hereditary succession to the throne was unimpeachable. It was no Bosworth Field for which they were heading, they were not advancing a rival dynasty, but they were seeking to establish, or to reestablish, a constitution. In doing this they could either regard themselves as rebels, in which case they had to prove that their

rebellion was justified; or, if they chose not to regard themselves as rebels, they had to prove that they, that Parliament, was constitutionally and legislatively supreme. At the beginning of the struggle they sought to avoid the issue by such tortuous reasoning as that they were fighting not the King but his evil counsellors. But soon they were seeking justification in precedent no less diligently than Charles had done, relying upon the common law as expounded by Coke, upon statute law (but not recent statute law for this was too closely associated with the regime they were opposing), upon the ancient constitution, upon real or imagined history, and upon the very principles of political obligation. They selected for approval certain landmarks, particularly Magna Carta and their own Petition of Right: the former, being the more remote, was particularly useful and its clauses concerning free men and imprisonment were particularly apt. They spoke of a golden age where all men were free. They explained the need for such charters as Magna Carta by adopting the fiction of a free Anglo-Saxon society upon whom the Norman yoke had been riveted by William the Conqueror. Events subsequent to the Norman Conquest then became the winning back of lost freedoms by the people of England and the present struggle could be seen as one event — supposedly the last — in such a chain.

There still remained difficulties in deciding what was a good law and what a bad law. Pym had said, and his words were widely echoed throughout the conflict, that the law is that which puts a difference between good and evil, between right and wrong. But people could ask: whose law? and attention was turned to the 94th Psalm with its profound assertion of possible evil in the law-giver — 'he who frameth mischief by a law'. By what yard-stick should a law be judged? There were many answers, but the terms 'natural law' and 'fundamental law' began to take their places in the pamphlet literature. But what was 'natural' or 'fundamental' law? Was it always beneficial? And, if beneficial, to whom? The protagonists looked even further back than Anglo-Saxon society to a 'state of nature' whose inhabitants voluntarily abrogated their authority in favour of one or some who would act for them. Generally they thought in terms of a monarch who made a compact with his people which was repeated in the Coronation oath of subsequent kings. This brought the opposition on to surer ground. If an anointed monarch broke his coronation oath might he not be replaced, as having broken the original compact made between ruler and ruled?

At this point they had a wide literature to call upon. In the French wars of religion the question of deposing an unsatisfactory king had been widely canvassed, and though the context had been for the most part religious, the issue was much the same. The author of the Vindiciae contra tyrannos , published in 1574, asked squarely whether subjects ought to obey Princes who commanded that which was against the law of God, or whether they should resist a Prince whose actions were oppressive or ruinous to the state? It was the easier for Parliament to supply the answer since so much of their Puritan tradition was concerned with resistance first to the Pope and then to a persecuting monarch. 'Think you that subjects, having power, may resist their princes?' was the first question that Charles's grandmother, Mary, Queen of Scots, put to John Knox on their first meeting.

Behind the question of obedience lay a second, and even more profound, question: in whom does sovereign power reside? Parliament answered emphatically that it itself was sovereign and, not surprisingly, its old champion, William Prynne, weighed in heavily with a long, tortuous, and margin-ridden treatise on The Sovereign Power of Parliaments . Behind the verbiage he and others were claiming that Parliament was supreme because it was representative, but since the right to vote was vested in property owners, a considerable sleight of hand was necessary to carry through the assertion that Parliament was representative in the full sense of representing all the people.

For Charles the questions were more easily formulated and simpler to answer. He was defending his position as monarch by divine right, heredity, and anointment, holding his prerogative, 'the fairest jewel in his crown', to use in case of necessity and claiming to rest his government upon the law and his people assembled in Parliament. His contribution to the paper war was consequently smaller in volume than that of his opponents. Generally speaking, the Royalist writers agreed with the King but got into difficulties in trying to combine a semi-mystical approach to sovereignty with the recognition that the King was subject to law and that law could be made only with and through the Parliament. Nevertheless they were unequivocal in refusing to recognize a right of resistance to the sovereign by Parliament or anyone else. In any case, wrote John Bramhall in 1643, the kingdom had suffered more from resistance in one year than under all the kings and queens of England since the union of the two roses. As for the liberty which Parliamentarian supporters were claiming, this could be expressed only through the law, and then very inadequately. 'The true

debate among men', wrote Dudley Digges in The Unlawfulness of Subjects taking up arms , published in 1643, 'is not whether they shall admit of bonds, but who shall impose them. Though we naturally delight in a full and absolute liberty', he continued, 'yet the love of it is over-balanced with fears . . . that all others should enjoy the same freedom.'

The principles under discussion were of basic importance yet they brought no nearer a solution of the differences between Charles and his Parliament. But, although the drift to war was unmistakeable, no one would yet admit of such a bleak development. The pamphlet war that for a few brief months took the place of physical conflict was partly a desire for justification, but partly also an effort to avert the inevitable catastrophe. Certainty existed in the minds of only a few — and these, perhaps, were the lucky ones. Some simply wished to remain neutral in a quarrel which barely touched their lives. For others the doubts and questioning were intense and resulted in rifts that ran through Parliament, through counties, through towns, through families. Possibly half the peers had by now come into the King and about a quarter were uncommitted, leaving a quarter who were still with the opposition. Of the Commons only a minority had so far decided for him. Towns were divided, as Charles had seen at Hull. Families were divided, his Knight Marshall, Sir Edmund Verney, remaining with him while of the Verney sons one was with Parliament, the other with his father. Yet it was impossible for the two sides to remain locked in words and movement of some kind was inevitable. Predictably the incidents piled up. Militia Ordinance and Commission of Array were the most obvious points of conflict, openly juxtaposing the two sides. Lord Paget, originally a Parliament man, was driven by the Militia Ordnance to change sides:

my ends were the common good, and whilst that was prosecuted, I was ready to lay down both my life and fortune; but when I found a preparation of arms against the King under the shadow of loyalty, I rather resolved to obey a good conscience than particular ends, and am now on my way to his Majesty, where I will throw myself down at his feet, and die a loyal subject.

Religious differences, which perhaps had been tolerated amongst friends and neighbours, became more irritating; personal feuds took on a wider significance. The Earl of Warwick used the ships under his command to remove the arms stored at Hull and convey them to the

Tower of London. Charles made a further vain attempt to win over Hotham and take the town on July 17. He began to move southwards and westwards from York, assessing allegience, gathering support, collecting money and plate to convert into coin. On July 9 he appointed the Earl of Lindsey Commander-in-Chief of the forces he believed he could raise. Robert Bertie, Lord Willoughby de Eresby, had been created Earl of Lindsey for services under Buckingham at La Rochelle. He had seen energetic campaigning in Europe and adventures on the Spanish Main that smacked of successful piracy. He had made an advantageous marriage, improved his estates at Grimsthorpe Castle near Stamford, and did well out of Fen drainage. He was physically tough, outspoken, and almost boisterous in his manner. He was a good all-rounder to have as Commander-in-Chief.

Three days after Charles had made his choice Parliament named the Earl of Essex Captain General of the Parliamentarian army which, they oddly claimed, had been levied 'for the safety of the King's person, the defence of both Houses of Parliament, and of those who have obeyed their orders and commands, and for the preservation of the true religion, laws, liberties and peace of the kingdom'. Essex was brave, but lethargic. His coffin, his winding-sheet and his scutcheon accompanied him on his campaigns and he took no notice when Charles declared him a traitor.

It was now a question of a definitive act that would be a declaration of war and Charles decided to raise his standard. But where? The Lancashire tenantry were following their hereditary leaders, the Stanleys, and it was in Manchester, in opposition to Parliament's Militia Ordinance, that there occurred on July 15 one of the first skirmishes of the war. In Northumberland and Durham the Earl of Newcastle was marshalling his tenants for the King and was in possession of Newcastle, Shields and Tynemouth Castle. Herefordshire, Worcestershire, parts of Warwickshire, were friendly, and in Wales he could count upon strong support. Finally, against a strong case for Lancashire, Charles decided in favour of Nottingham, a compromise position between the North and Wales, well placed by river communication with the Eastern seaports where, in place of Hull, his wife's arms might land, and conveniently near to London. For, insofar as he already had an objective, it was the capital with its prestige, its wealth, its possible Royalism once the influence of Parliament was broken, its access by sea north wards and to the Continent, its radius of communications over the country, and its appeal as his home and the

seat of his government throughout his reign: he might well be regretting the night of panic that caused him to leave his capital city.

The raising of his standard at Nottingham on August 22 was not the dramatic affair that Charles could have wished. He had been refused entry to Coventry two days before and a Proclamation calling for support had not attracted the numbers he expected. For various reasons — uncertainty, bad weather, the requirements of harvest — there was no vast or enthusiastic concourse at Nottingham and it was not until six in the evening of a bleak and stormy day that Charles, his two sons, his nephews Rupert and Maurice who had lately joined him, Dr Harvey, a few courtiers, the heralds, and Sir Edmund Verney with the standard, rode to the top of Castle Hill. As the pennant was unfurled and a herald, with a flourish of trumpets, made to read a proclamation, Charles snatched the paper from him and hurriedly scribbled some amendments as best he might in the blustery wind, with the consequence that the herald, stumbling over the spidery handwriting, failed to make the dramatic summons that was called for. Later in the week the standard was blown down.

On that fateful day Charles had no more than 800 horse and 3000 foot that he could call an army. He commissioned Prince Rupert, who already had won a considerable reputation as a cavalry officer in Europe, as General of Horse, confirming the appointment made by Henrietta-Maria in his name. Although his wife had sent a warning that the Prince was still young and headstrong and needed watching, Charles granted Rupert's request that his command should be independent of the Commander-in-Chief and that he should be accountable to the King alone. His mother had tried hard to keep him in Europe, away from the maelstrom she saw developing in England and closer to the scene of his hereditary struggle, but Rupert equalled her in force of character; he not only came himself but brought his younger brother, Maurice, Bernard de Gomme, a skilled draughtsman and engineer with experience in siege warfare, and Bartholomew La Roche, a 'fireworker', who would be useful in the artillery train.

Perhaps because of the paucity of his following, perhaps through fear of the irreversible step, Charles's advisers called for one more approach to Parliament. For once Charles opposed this advice. In his slow fashion he had at last accepted war and he would not be thrown back into an agony of indecision. When he at last yielded, it was with bitter tears of frustration. But he had been right. Parliament scornfully

rejected his overtures. Only if he furled his standard and recalled his declaration of treason against their commanders would they treat.

Charles's frustration had been caused partly because he knew that further attempts at negotiation would be fruitless, partly because he wanted to vindicate himself in his wife's eyes and to free himself from the terrible scorn she was pouring upon his diffidence and uncertainties.

Henrietta-Maria was by this time firmly established at The Hague, where she and the Princess Mary had arrived on February 25 to a welcome which was warm if not enthusiastic. In the welcoming party was her sister-in-law, Elizabeth, with her youngest daughter, Sophie, who was about the same age as Mary. The anxieties of the past year had left their mark on the Queen and a rough Channel crossing in which one of the baggage ships sunk within sight of land had not improved her looks. Little Sophie, who had been deeply impressed by the Van Dyck portraits of her aunt, was sadly disappointed at the sight of what she later described as a little, lop-sided lady with big teenth but who nevertheless possessed beautiful big eyes and a good complexion. Sophie was far more impressed with her elegant cousin and was highly flattered when Henrietta-Maria commented upon a likeness between the two children.[3] It was the first meeting between the two mothers — Charles's sister and Charles's wife — and they rode in the same carriage with William and Mary, talking earnestly.

Henrietta-Maria was comfortably lodged in the new palace of the Prince of Orange, but she soon made it clear that her object was solely that of supplying her husband with money and arms. There were difficulties in selling or pawning the jewels she had brought with her, for dealers were reluctant to touch anything that might belong to the Crown; security for a loan was similarly difficult to obtain. In long letters in cypher to Charles she related her experiences and told him what he must do. It was evident that she felt the need to bolster his resolution and was afraid of the mistakes he might make without her presence. Nothing so much indicates the hold she had over Charles as her letters from Holland. When she heard he had been denied at Hull she was first incredulous, then scathing. She had left England, she wrote, so that he would not be hampered by feelings of responsibility towards her. Now she perceived it was not thoughts for her but his own weakness which impeded him. She herself had long ago accepted the necessity for war and urged her husband over and over again not to delay his preparations. 'Delays have always ruined you', she wrote, no

doubt thinking of the Five Members. She accused him of being up to his 'old game of yielding everything'. She, who knew him so well, and who had made light of his faults when they appeared to be of little significance, now, in time of stress, remembered them all, and Charles accepted her strictures. He did nothing without his wife's approbation, wrote Elizabeth to Roe about this time.

Henrietta-Maria drove herself to extremities of fatigue by poring over Charles's cypher letters. She was terrified lest he should lose the code. She had noted his habit of thrusting things into pockets and saw that he had done the same with the precious cypher: 'take care of your pocket', she admonishes, 'and do not let our cipher be stolen.' Her endeavours were reflected in her health. Not only were her eyes troubling her, her head ached, she had pains in her legs and was becoming lame, she was distracted by toothache and had a severe cold. The difficulties of communication alone were sufficient to deter a less resolute woman. Little Will Murray, as Henrietta-Maria always called him — was he shorter even than Charles or herself? — the two brothers Slingsby, Sir Lewis Dyve, Walter Montague her chaplain, were among their go-betweens. But the weather delayed vessels, Parliament's shipping was strong in the Channel, one vessel carrying letters was driven back to Brill after four days at sea, on another occasion a bag of letters was jettisoned through fear of capture and it was some time before it could safely be fished up again. They supplemented the letters with agents of various kinds — a 'poor woman' at Portsmouth, a man who came to Holland ostensibly as a bird-catcher and who reached the Queen a fortnight after he left Charles. But it was inevitable there should be gaps filled on the Queen's side, at least, with conflicting rumours. On one occasion she was so tormented by stories of defeat and death that she made her way in disguise to a bookshop which stocked corrantos or news-sheets, but fled on being recognized. Some of Charles's letters giving details of his requirements nevertheless reached her and she was having some success in raising money and in buying arms. Some things she merely pawned, hoping to acquire them again in better days — her 'great chain' and the cross from her mother. But she sold her 'little chain' and dismembered Charles's pearl buttons: 'You cannot imagine how handsome the buttons were, when they were out of the gold, and strung into a chain . . . I assure you, that I gave them up with no small regret.'

While his wife's activities gave him hope of assistance and stiffened his resolution, Charles still had to bear the anguish of separation, the

worry of her ill-health, the difficulties of communication, and at the same time prepare for war. Her letters, indeed, aroused mixed feelings and her forceful comments on his character could be painful in the extreme. Yet her letters were also the most poignant love letters. 'If I do not turn mad', she wrote, "I shall be a great miracle; but, provided it be in your service, I shall be content — only if it be when I am with you, for I can no longer live as I am without you.'[4]

30—

Commander-in-Chief

After his standard had been somewhat ignominiously floated at Nottingham Charles moved westward to gather the support he believed to be awaiting him in Shropshire and in Wales. He left Nottingham on the 13th for Derby, where the miners came into him in considerable strength, mostly joining the Lifeguard commanded by Lord Willoughby d'Eresby; he was welcomed at Shrewsbury on the 20th where he was joined by Patrick Ruthven with twenty or so experienced officers. Baron Ruthven of Ettrick was a hard-drinking, experienced soldier, already some seventy years of age, who had seen much service in the European wars and been Charles's Muster-Master in Scotland and Governor of Edinburgh Castle. In his pleasure at seeing him Charles now created him Earl of Forth. At Chester on the 23rd recruits began to flock in, not only from the immediate neighbourhood but, as expected, from North and South Wales and from Staffordshire, and also from Lincolnshire, Bedfordshire, and further afield.

The Parliamentarian forces under Essex had hoped to surprise the King at Nottingham, but, learning of his departure, had stopped at Northampton and on the 19th began a westward march towards Worcester parallel to the King's own. Worcester had opened its gates to Royalist troops but Rupert, probably correctly, judged the city untenable against Essex's advancing army and was covering the Royalist evacuation of the town when, quite accidentally, he fell in with a small group of Parliamentarian horse at Powicke Bridge. Rupert had the advantage of seeing the enemy before they saw him and in a brief little encounter on 23 September 1642 the first real engagement of the war occurred, in which the Parliamentarian horse broke and fled, not drawing rein until they had joined their main army, many miles away. The news of Powicke Bridge was brought to

Charles at Chester by Richard Crane, Commander of Rupert's Lifeguard, who was knighted on the spot by the delighted King. Though only about 2000 men in all had been involved Charles had, indeed, cause for satisfaction as he gleefully examined the six or seven captured cornets of horse who were brought in. First blood of the war had gone to him and casualties were few, though among the wounded were his nephew, Maurice, and his friend, Sir Lewis Dyve.

In common with the majority of the men who were joining up on either side, Charles had to learn the strategy of war in a country like England. Some of the recruits had had experience in Germany or the Low Countries, some had fought under Gustavus Adolphus and were familiar with the Swedish form of fighting, others favoured the simpler Dutch formations. Some, like the King himself, had experimented for hours with model soldiers and artillery. None of them had fought before on English soil with its own particular problems. Where fields had been enclosed, for example, there was little opportunity for deploying an army — certainly not the cavalry — and the weather played its part. Roads were execrable, bad enough for individual horsemen, almost impassable for the numbers who were now beginning to turn even the best of them into mud and quagmire as the ruts and holes common to most surfaces were filled to over-flowing by the heavy rains of September 1642. For men to be kneedeep in mud and water was not uncommon, while horses, carts, waggons and coaches had to be pushed and hauled time and time again through the enveloping slime. The drill books and manuals of war that were brought out might in some respects put a captain ahead of his men, but they gave no real insight into the situation. Neither side, for example, had envisaged the number of horses that were needed — not for the cavalry since volunteers brought their own mounts — but cart horses for drawing gun-carriages and other heavy vehicles. It took six or eight cart horses, harnessed in tandem, to pull a field gun; the heaviest cannon required twelve or fourteen. Charles, whose study of warfare had familiarized him with the problem, had encouraged James Wemyss, his Master Gunner, to produce a lighter and more mobile piece of artillery. Wemyss had actually constructed a gun consisting of a copper tube strengthened with iron bands and covered by a leather skin, but this had not yet come into general production, and markets and farms for miles around Charles's army were being scoured for horses and, failing horses for oxen, to draw his heavy guns. Carts and wagons were in similar demand for conveyance, and

denuded farms were paid by the day for their use, with a bonus if the driver came too.

Food, fodder, the paraphernalia of cooking and eating, cooks, provisioners, traders anxious to provide anything that was required for man or beast; shovels, spades, pickaxes, wheelbarrows; ropes, spare harness, materials to repair the constant breakages which the conditions of travel entailed, came along with the army. In particular a contingent of smiths and wheelrights were there, for the roads played havoc with horses' hooves and with the wheels of vehicles, and in hostile country the inability to secure the services of these craftsmen could be very serious.

Normally the Royalist army on the march consisted of two brigades of cavalry in the van, followed by a brigade of foot. Charles followed on horseback supported by his Lifeguard with his banner and flanked by his Council of War, with secretaries and messengers to hand. There followed another infantry brigade and then the enormous and unwieldy artillery train protected by musketeers, the horses pulling desperately at the heavy guns and at the carts and wagons loaded with arms and ammunition. Courtiers and courtiers-turned-soldier frequently brought their wives who travelled in carriages. They all brought much personal baggage. Even the lower-ranking soldiers came with their wives, their wardrobes and their household goods, while the secretariat had its own wagon of writing materials, documents, letters, duplicates, the King had his personal wardrobe and his more private correspondence, prostitutes cheerfully tagged along, and in the rear a further brigade of cavalry, sometimes in front of, sometimes behind the baggage trains, completed the tale of an army marching to war. The untidy, heterogeneous procession covered some five miles or more from van to rear of the muddy and difficult roads of the Midlands, moving so slowly that it took Charles ten days to cover less than a hundred miles between Shrewsbury and Banbury, which was not considered bad going and which was better than Essex did on his nearly parallel journey from Worcester to Kineton when he averaged only eight or so miles a day, and then left part of his army far in the rear.

The army carried few tents and little camping equipment, so the surrounding countryside was scoured to find billets for the 12,000 or so troops on the move. Charles and the High Command generally lodged in some nobleman's house while the men slept in scattered villages as far as ten miles away. The total area occupied by an army,

simply to move from one place to another, was very considerable. Though provisions were at first paid for and often eaten in camp, it is understandable that the advent of an army came to be dreaded and that its passage was likened to the passing of a horde of locusts. It would seem difficult to conceal its whereabouts. Yet, in spite of the strategy learned on the Continent and the frequent recourse to drill books and military manuals, the art of reconniassance was so lacking, or so extremely elementary, that commanders frequently seemed unaware of the presence of the enemy until they were on top of them.[1]

After Powicke Bridge there had been some discussion of strategy among Charles's High Command: should they engage Essex then and there and endeavour to take Worcester? Or should they march on London? The former was ruled out partly because the enclosed nature of the countryside made cavalry deployment difficult, and partly because Charles's growing resources made the bolder plan viable. His armies were increasing daily and he now had no scruples in accepting Catholic money or plate or, indeed, Catholic services: 'this rebellion is grown to that height', he wrote to Newcastle, 'that I must not look what opinion men are who at this time are willing and able to serve me'.[2] He left Shrewsbury on October 12, making for London in a south-easterly course with some idea of taking Banbury on the way. Passing between hostile Warwick and Coventry he stopped at Southam and reached Edgcott, four miles from Banbury, on the evening of October 22, where he lodged at Sir William Chancie's house with Rupert nine miles away at Wormleighton, Lindsey at Culworth, and his men dispersed to such scattered quarters as they could find. The weather was atrocious and bitterly cold. About midnight Rupert sent word that Essex, who had been on the shorter march from Worcester, was at Kineton, some seven miles west of the main Royalist position. The two armies, though they marched the same way and had been only twenty miles apart when they started, and for the last two days had been on a parallel course only ten miles apart, had until then no knowledge of the whereabouts of each other.

There was danger to Charles in continuing his march with Essex in his rear, so when Rupert reported in favour of battle Charles readily accepted his advice. 'Nephew', he hurriedly scribbled, 'I have given order as you have desyred; so I dout not but all the foot and canon will bee at Edgehill betymes this morning, where you will also find Your loving oncle and faithful frend.' Discussions concerning tactics soon reached deadlock; Lindsey favoured the Dutch order of battle, Rupert

the Swedish in which pikemen and musketeers were interspersed in the battle line-up, and Charles supported his nephew. The fatal flaw in the command which allowed Rupert to be independent of the Commander-in-Chief had already led to difficulties and now the volatile and haughty Prince appeared to be taking over the whole strategy of the battle, foot as well as horse. When Lindsey cast his baton on the ground declaring: 'Since your Majesty thinks me not fit to perform the office of Commander-in-Chief I would serve you as colonel only', Charles cut the Gordian knot by instructing Lord Forth to draw up the army in battle order while he himself assumed the overall command.

The ridge of Edgehill, where the Royalists would take up their position, was some five miles west of Edgcott and only two miles from Kineton. By early morning Rupert's horse were drawn up on the ridge and Charles was gazing through his perspective glass at the awakening Parliamentarian armies below. It was afternoon by the time the Royalist foot had been brought in from the scattered villages where they lay, and by that time Essex had collected the main body of his army and had deployed it in one of the open fields of that still largely unenclosed countryside. He was perturbed at the numbers he saw massing against him, which far exceeded any reports he had received, particularly since two of his regiments of foot and one of horse were a day's march behind him. He did the only thing that was open to him. He stayed where he was and waited for the enemy to attack. Charles meantime, having sent his sons firmly away to comparative safety in the charge of the faithful Dr Harvey, was riding up and down amongst his men with a black cloak over his armour encouraging everyone. By three o'clock they were ready. 'Go in the name of God', he said to Lindsey, 'and I'll lay my bones by yours.' He had under his command some 2800 horse, 10,500 foot, 1000 dragoons, and some twenty guns drawn up, in customary fashion, with the foot in the centre and the cavalry on each flank. Many prayers went up that day. Sir Edmund Verney, bearing the royal standard in a conflict he could not believe in; Lord Lindsey, no less determined to fight in the King's forces although he was no longer their leader; Lord Falkland, no fighter by inclination and hoping to end the strife in one swift blow; cavaliers who had followed Rupert from Europe; courtiers, excited and scornful of the enemy; country gentlemen and their sons whose only experience of war was in the tales of their fathers and the dusty textbooks they had routed out; raw recruits, frightened and

uncertain, whose instinct was to break and run for home; Charles himself whose baptism in battle was about to begin; seasoned veterans like Sir Jacob Astley whose spoken prayer served for them all: 'O Lord!, Thou knowest how busy I must be this day. If I forget Thee, do not Thou forget me'.

Rupert, on the right of the King's army, was the first to charge using the full weight of his horsemen, in his accustomed style, to break the enemy, reserving his fire for the pursuit. The Parliamentarian left wing was shattered by the impact. Rupert and his cavaliers pursued the fleeing horsemen to Kineton and beyond, only drawing rein when two of Hampden's regiments were seen advancing towards them. The Royalist left wing had acted similarly, if not so dramatically, and the brunt of the fighting in the field had been left to the two blocs of infantry where Charles remained, urging on his men, commanding mercy to the enemy, in the midst of terrible slaughter. His commanders begged him to retire to the top of the hill, which he did for a while, but he was soon down amongst his men again. As evening fell Rupert's horsemen returned to the battle which might have been decisively won but for their long absence. Falkland urged one more charge, possibly thinking to end the war then and there, but it was too late; men and horses were spent and darkness was falling. Charles refused to leave the field lest the enemy attempt another attack or construe his withdrawal into an admission of defeat. He slept fitfully in the uncertain light and scant warmth of a small fire made from such wood and brush as could be found, the dead and wounded of both armies lying near him on the battlefield. Before he slept he rewarded one act of heroism, while mourning its necessity. Verney had fallen in the battle and the royal standard had been seized, but Captain Smith, slipping through the enemy lines after dark with a few comrades, recaptured it and brought it to the King, who knighted him on the spot. He had no news of Lindsey, or of Lindsey's son, who had last been seen standing over his wounded father in an attempt to save him.

By first light the wounded were being brought in and the dead identified. They had lost some 1500 men in all. Lindsey's son was a prisoner, Lindsey himself had been carried to a barn where he lay without medical attention, bleeding to death; others who remained in the cold of the battlefield all night fared better, as Harvey recorded, for the frost congealed the blood on their wounds. It was soon apparent that Essex was moving off to Warwick, and the way to London was open to Charles. If the battle itself had been indecisive the result of the

battle was a victory for the King, for it had achieved his objective.[3] Rupert proposed to the Council of War that a flying column of 3000 horse and foot should immediately march on Westminster and take the capital by surprise. Charles could not bring himself to entertain so immediate a confrontation. But neither, it seems, could he envisage a more sober approach to the city. Instead he marched to Banbury, where he secured supplies of food and clothing for his men, and he captured Broughton Castle, doubtless deriving satisfaction from the knowledge that he was master in the Puritan territory of Lord Saye and Sele. He and his army then moved forward unmolested to Oxford, whose loyalty to the King was unquestioned in spite of some difference of opinion between the town and the University. But in doing this he allowed Essex to make a leisurely return to the capital. Neither side hurried. The initial impact of civil war had been sobering and the armies were not yet willing to risk a fresh encounter. But Charles, by the delay, lost more than his opponents, for he never again had the opportunity of occupying London. Perhaps, thereby, he lost the war.

Charles entered Oxford on October 29 at full march accompanied by the four Princes and with the sixty or seventy colours captured at Edgehill borne before him. The welcome was warm and the mayor presented him with a bag of money. The deputy orator welcomed him more effusively for the University and, with his sons, he took up residence in Christ Church, while Rupert went to St John's where, in Laud's time, he had been accepted as a commoner. The foot-soldiers were billeted in the villages round Oxford, the cavalry headquarters were at Abingdon, many important officials remained near the King — Culpepper and his family in Oriel College, other members of the Privy Council in Postmaster's Hall opposite Merton College where the Warden's lodgings were being prepared for Henrietta-Maria.

The arms and ammunition they brought with them joined the stores already in the cloisters and tower of New College, twenty-seven pieces of heavy ordnance were driven into Magdalen Grove. Grain was stored in the Law and Logic Schools, fodder in New College, animals were penned in Christ Church quadrangle. In the Music and Astronomy Schools cloth was cut into coats for soldiers and carried out by packhorse to be stitched by seamstresses in nearby villages. The mill at Osney became a gunpowder factory, a mint was erected at New Inn Hall to turn the plate that had been brought in to

the King into negotiable money. Nicholas Briot's assistant, Thomas Rawlins, who was with Charles, had much of his master's skill and, apart from utilitarian pieces needed for soldiers' pay, the mint produced a beautiful golden crown piece to his design and a medal to mark the victory at Edgehill — for so the Royalists termed it, though Charles was well aware of the greater victory it might have been, as he told the Venetian Ambassador who visited him at Christ Church; if the cavalry had not overcharged and returned to the field too late to do further battle, he said, it would have been a great victory indeed.

Charles made one not very convincing attempt to march on London when Rupert, on November 11, took and briefly held, a Parliamentary outpost at Brentford. But the London trained bands streamed out to protect their city, and faced with a force of 24,000 men, outnumbering him by two to one, Charles withdrew. He might have crossed into Kent at Kingston and drawn upon the support for him there, but the campaigning season was over and he preferred to settle down in Oxford for the winter. The fortifications of the city, begun before Charles's arrival, were continued. The High Street was blocked at East Bridge by logs and a timber gate, while a bulwark between it and the Physic Garden wall supported two pieces of ordnance, and loads of stone were carried up Magdalen Tower to fling down upon the enemy. The digging of trenches was ordered at vulnerable points between St John's College and the New Park, and in Christ Church Meadow, but the response was poor and when Charles reviewed the work he spoke to the citizens personally, afterwards issuing an Order that everyone over the age of sixteen and under sixty should work on fortifications for one day a week or pay twelve pence for each default. Plans were made to use the waters of the Thames and Cherwell, which surrounded the city on all sides except the North, as an additional defence, the vulnerable North being protected by regiments at Enstone, Woodstock, and Islip. Communications with Reading, which the Royalists held, were kept open by garrisons at Wallingford and Abingdon. Strong garrisons at Banbury, Brill, Faringdon and Burford completed an outer ring of defences behind which Charles at last had a little time for contemplation as he and his army settled in for the winter.

But first he attended to the pleasant task of honouring his children by conferring the degrees of MA upon them; for Dr Harvey, Cambridge and Padua, there was the distinction of an Oxford MD. So

popular among his followers were these awards that Charles found himself sponsoring 18 Doctors and 48 Bachelors of Divinity; 34 Doctors and 14 Bachelors of Civil Law; five Doctors and eight Bachelors of Physics; 76 MAs and 12 BAs. As the day of inauguration wore on the Chancellor's actions became more mechanical, his attention lapsed, and many men who had not been named thrust themselves forward after candlelight to receive the coveted honour. The granting of degrees was an easy way for Charles to reward his followers, and by the following February the University was tired out with one Convocation after another and Charles, without ill-will, agreed to curtail his academic awards.[4]

Meanwhile printing presses, many of them clandestine, were proliferating, especially in London, giving vent to every kind of opinion, religious, social, political; reporting battles, conferences, proceedings in Parliament or in Oxford. They came from both sides and neither side and voiced complaints that could be laid at the door of either party or no party, they proposed solutions that were practical or Utopian, they expressed new antagonisms, new alignments as the struggle proceeded and they reflected every shade of opinion and belief that the violent opening of society generated. A London bookseller, George Thomason, set out to collect a copy of every pamphlet and news-sheet that came his way from the beginning of the Long Parliament. For the year 1642, the peak year, he had well over 2000 and the numbers were always well over a thousand. They included the news-sheets which were the successors of the corrantos brought to England from Holland during the earlier stages of the Thirty Years War and which now began to appear as regular weekly newspapers. Charles had been as quick as anyone to appreciate the value of print and of regular reporting. He took a printing press with him when he left London and one of the first things he did in Oxford was to inaugurate a weekly news-sheet. Its first appearance as Mercurius Aulicus in January 1643 was preceded by a few days by Parliament's Kingdomes Weekly Intelligencer. Aulicus was published from Oriel College under the editorship of Dr Peter Heylin, the Laudian divine, but its leader-writer and subsequent editor was Sir John Berkenhead, a brilliant protégé of William Laud, a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, who had worked for some time with the Archbishop at Lambeth Palace. Aulicus seems to have had two printing presses at Oxford and, remarkably, it was also printed in London. The opening paragraph of the first number referred to its

rival — 'a weekly cheat' put out to nourish falsehood amongst the people and 'make them pay for their seducement'. Aulicus would make them see 'that the Court is neither so barren of intelligence . . . nor the affaires thereof in so unprosperous a condition, as these Pamphlets make them'. In its 118 numbers, ending with the issue of 31 August — 7 September, 1645, Aulicus maintained a high standard of informed and witty reporting, receiving its news items and effecting a system of distribution and sale in and out of Oxford and even in London under the very eyes of Parliament.[5] It competed with some 170 different news-sheets which appeared for longer or shorter periods and hundreds of pamphlets, many of which made their way to Oxford. Charles was enormously interested in all the pamphlet literature. Early in January 1643, for example, The Complaint of London, Westminster, and the parts adjoyning was being read to him while he was taking supper and he did not rise until it was finished.

Insofar as it was possible to make any calculation at this stage, it seemed that a majority of the House of Lords were following Charles and some forty per cent of the Commons, which was considerably more than the attitude of either House had indicated in the early days of the Long Parliament. Of the Commons possibly 236 Members were Royalists, most of whom had joined him, while 302 remained at Westminster. The tenants of the great landowners were for the most part following their lords — if they did not stay away from battle in an effort at neutrality; industrial towns, particularly the clothing towns of Lancashire, were for Puritanism and Parliament, while the surrounding areas, which contained many Catholics, were for the King. Similarly Bradford and Halifax contributed much support for Parliament, while round them rural areas followed the Royalist allegiance of their landlords. On the whole Charles had great hopes of the North, where he had appointed the Duke of Newcastle Commander of the four northern counties; in March 1643 he stiffened the inexperienced lord by giving him James King, Lord Eythin, a Scot who had seen active service on the Continent, as his Lieutenant-General. By the middle of December Newcastle was virtually in control of Yorkshire, and Lord Fairfax, the Parliamentarian Commander, had fallen back to Selby. In Cornwall the Marquess of Hertford, William Seymour — at one time the husband of the unhappy Arabella Stuart — who was Lieutenant General of the Western Counties, was in virtually complete control, with Ralph, Lord Hopton, his second-in-command and

such men as Bevil Grenville, grandson of the hero of the Revenge , fighting with him.

Charles's opponents had the advantage of London, of most of the wealthy towns and important ports, but south of the capital he could count on support in Kent. Roughly speaking, Charles might call the North and the South-West, including Wales and Cornwall, his country, the East and South-East Parliamenterian country, with the Midlands somewhat unevenly divided in favour of Parliament. But everywhere there were pockets of individual allegiance, and all over the country great houses were standing out in hostile territory. Charles saw among his own supporters large and small landowners, old landed families and new, merchants, industrialists, lawyers, rising gentry and falling gentry — but he saw them on the other side, too. Even past favours had not guaranteed support. He wryly watched the Earl of Holland with his friends of the Providence Island Company, and he wondered why Wemyss, his master gunner, with whom he had appeared to be on good terms, had taken up arms on the other side.

Why, indeed, were they fighting at all? Edward Hyde had often told him that the number of those who desired to sit still was greater than those who desired to engage on either side, and the philosopher Thomas Hobbes was saying that there were few of the common people who cared much for either of the causes, but that most would have taken either side for pay or plunder. There certainly had been reasons for the antagonism of the Long Parliament. But that was past history. The abuses of which they complained had been removed, the constitutional government they demanded had been secured by the summer of 1641. Was it purely rancour that made people fight against him? Were they remembering the past — the forced loans, the monopolies in which they did not share, the tonnage and poundage, so necessary a tax in an untaxed country like England, lack of preferment at Court or in office, the enclosure prohibitions and the accompanying fines at which Laud had been so adept, his own knighthood fees, forest fines and the ship money he had used for the ships which now were in Parliament's hands? If Charles had given way on the militia could he have averted war? Was it over the control of the armed forces that they were fighting? If he had abandoned Episcopacy would he have averted war? But they had not wished him to do that, as the debates on the Grand Remonstrance and the opposition to the Root and Branch Bill made abundantly clear. Did they really believe that he

was so lukewarm in his religion, or so much under the influence of his wife, as to consider joining the Roman Church? Did they consider for a moment that his relations with Spain were anything but opportunist or that he had in any way encouraged the Irish rising in 1641? He remembered angrily that the people who now accused him of betraying the Protestant religion were the very ones who had refused aid to his sister. He still could not see why a compromise had not been reached. Had Bedford served him ill by his death at the moment when a middle group might have negotiated a settlement? But, whatever the answers, it takes two to make a quarrel and it takes two armies to wage war, and unless there had been a significant reaction against Parliament the formation of a King's party would have been unlikely and the outbreak of war impossible.

Possibly the split had occurred between those who believed in his promises and those who did not believe that he had abandoned forever the right to supply without the sanction of Parliament. But a tax would be a tax, money would be required, whether for King or Parliament, and Charles could watch, even with amusement, the response accorded to his opponents' efforts to raise money. When Pym had met with a poor response from the City earlier in 1642 and spoke of 'compelling' the Londoners to lend, their defences had gone up immediately. Certainly, said D'Ewes, 'if the least fear of this should grow, that men should be compelled to lend, all men will conceal their ready money, and lend nothing to us voluntarily'. There was a similar reaction at the end of December when the City refused to lend unless the Upper House set an example. Some noble lords refused absolutely, others took time to consider, Lord Saye subscribed a mere £100, the Earl of Manchester £300.

Many people undoubtedly believed that to continue the quarrel with the King would be to unleash anarchy, and in this respect the petitions and rioting at the end of 1641, which Parliament itself had encouraged, did them harm. The Venetian Ambassador noted the apprehension lest an attenuation of royal authority 'might not augment licence among the people with manifest danger that after shaking off the yoke of monarchy they might afterwards apply themselves to abase the nobility also and reduce the government of this realm to a complete democracy'. Sir John Hotham, a little too late for Charles's satisfaction, came over to the King's side after the fighting had started, giving as one of his reasons that he feared 'the necessitous people' of the whole kingdom would rise 'in mighty numbers, and whatsoever

they pretend for att first, within a while they will sett up for themselves to the utter ruine of all the Nobility and Gentry of the kingdome'. This danger of anarchy was one of the reasons for preserving episcopacy. As his father had said, no Bishop, no King; and Sir Edmund Waller had pointed out the relationship in greater detail. Episcopacy, he said, was 'a counterscarp, or outwork; which, if it be taken by this assault of the people . . . we may, in the next place, have as hard a task to defend our property as we have lately had to defend it from the Prerogative. If . . . they prevail for an equality in things ecclesiastical, the next demand perhaps may be lex agraria, the like equality in things temporal.' Or, as Sir John Strangeways put it in the course of the debate on the Root and Branch petition, 'If we make a parity in the Church we must come to a parity in the Commonwealth.'

As far as Charles could see the choice of sides rested almost entirely on the answer to the question whether property, and the civil and ecclesiastical order which upheld it, would be safer under King or Parliament. Those who supported Parliament might have had some doubts when in October 1642 a lawyer named Fountain appealed to the Petition of Right when refusing a 'gift' to Parliament and was told bluntly by Henry Marten that the Petition was intended to restrain kings, not parliaments. Fountain was sent to prison.

But while for richer people the issue had come to be very largely one of property, there were many who were now supporting Parliament under the wider banner which Charles's opponents had appropriated to themselves — that of 'Liberty' or, in the plural, 'Freedoms'. Charles could now see his mistakes in censoring the press, in allowing the 'Puritan martyrs' their platforms; he could see that 'little men', defeated by poverty, left behind by economic developments, were unafraid of anarchy but simply hoped for a new deal under Parliament; he knew well enough the power over these people of such fanatics as John Lilburne, who turned up as prisoner in Oxford after the taking of Brentford, having lost nothing of his old fire. In court he objected to being charged as a 'yeoman', being of gentry stock; he argued with the Earl of Northampton, and challenged Prince Rupert to combat, an unexpected invitation which caused the Prince to leave the room saying 'the fellow is mad!' In his captivity in Oxford Castle Lilburne kept up such a furore that the Royalists were only too happy to exchange him in May 1643 for Sir John Smith, whom Charles had knighted on Edgehill field.

The new Earl of Lindsey, who had remained a prisoner in Warwick Castle since Edgehill, was also exchanged in 1643 and joined the King. From such friends and supporters who came into him at Oxford Charles reaped great satisfaction. On the anniversary of Edgehill he called Edward Lake to him. Lake was a lawyer who, despite his inexperience, had shown remarkable bravery. When his left hand was shot he placed his horse's bridle in his teeth and fought with his sword in his right hand until the end of the day, when he was captured and imprisoned. Seven weeks later he escaped and made his way to Oxford. Charles was deeply impressed; 'you lost a great deal of blood for me that day', he said, 'and I shall not forget it.' Then, turning to the bystanders, 'for a lawyer', he said, 'a professed lawyer, to throw off his gown and fight so heartily for me, I must need think very well of it'. Charles not only created him a baronet but showed his habitual care over detail by taking a personal interest in Lake's proposed coat of arms, himself augmenting it by the addition of one of the lions of England.[6]

As winter set in at Oxford the Court of Whitehall reproduced itself as best it might. The city was now full of soldiers and courtiers, Privy Councillors, secretaries, officials and supporters of many kinds, mostly accompanied by their families, all crowding in on the limited accommodation, generally content to exchange their normal state for a couple of rooms in an overful lodging just for the sake of being there at all. Fashionably dressed ladies walked in college gardens or watched the recruits, mostly scholar-turned-soldier, marching down the High Street and out to the New Parks for martial exercise, or drilling in the meadows by the Cherwell under the walls of Merton College. Domestic troubles began to assert themselves: Prince Charles had the measles; Prince Maurice, more seriously, had an attack of the stone which worried his mother more than the war itself; Charles had to send to Whitehall for stockings and other small necessaries. The House of Commons debated whether a servant should be allowed to take them to Oxford and decided by a vote of 26 to 18 that Charles might have them. He did not know which was worse — the lack of interest in his needs or the fact that the matter should have been discussed at all. More serious was the news in March 1643 that Henrietta-Maria's chapel in Somerset House had been ransacked and that Parliament had sequestered the lands of bishops, deans and chapters, appropriating the income to their own use.

Meanwhile Charles played tennis with Rupert, he hunted as far away as Woodstock, he received Ambassadors, including the Venetian and the Frenchman, who was a constant visitor; he even did his best to celebrate a wedding when a Groom of his Bedchamber married the reigning beauty of the exiled Court. But all this was accompanied not only by the drilling of recruits and the construction of fortifications but by the clatter of cavalry as horsemen moved in and out of the city. The most advanced post of the Parliamenterian armies was at Windsor, where Essex was covering the western approaches to London, and while the armies of both sides lay in their wide-spreading winter quarters there was a constant movement of patrols, reconnaissance parties, and probing detachments of horse. The spring offensive was heralded when Parliamentarian forces took Reading, only twenty miles from Oxford. At the beginning of June they were in Thame and ventured into Wheatley but were beaten off by a Royalist garrison on Shotover Hill. Rupert disliked this forward probing and hoped to retaliate by securing a convoy of money which he had heard was on its way from London to Thame. He missed the convoy but on his way back to Oxford on June 18 he dispersed a small enemy force at Charlgrove Field, ten miles south-east of Oxford. In this little skirmish John Hampden was mortally wounded and died in Thame six days later. The removal of his moderating influence was a serious loss to Parliament.

The time was now approaching when Henrietta-Maria herself would be joining her husband with the arms and money she had collected. As they made plans for their reunion the couple set about deliberate deception. 'All the letters which I write by the post, in which there is no cipher, do not you believe', she instructed, 'for they are written for the Parliament.' So it was given out that she would land at Yarmouth or Boston, whereas she intended Newcastle or Scarborough. But as the time for her departure drew near communications failed completely. As Powicke Bridge and Edgehill were fought the couple were out of touch and only the most dramatic rumours reached the isolated Queen. At last, with communications restored, she set sail in January 1643. First her little flotilla was becalmed off the Dutch coast. When they finally got away they were struck by storms of unprecedented ferocity and for nine days were beaten to and fro off the Dutch shore with no opportunity of making land. The Queen sustained her terrified ladies by assuring them that Queens of England were never

drowned, acting at the same time as father-confessor to those who were convinced their end was near. When at last they were able to make land, it was Holland and not England to which they had come. The third effort was successful and Henrietta-Maria landed at Bridlington on February 22. She was given Royalist cover from the land and a troop of cavaliers rode in to greet her a few hours after her arrival. Charles was overwhelmed with relief and admiration: 'when I shall have done my part', he wrote from Oxford, 'I confess that I shall come short of what thou deservest of me.' Her trials were not yet over for the small house in which she prepared to spend the night became the target of bombardment from Parliamentarian ships and she was compelled to take to the shelter of fields and hedges while cannon shot burst round her. Even when she was ready to ride south there were difficulties, for Fairfax with his army lay between her and Oxford. It took her nearly five months to reach Stratford where she was met by Rupert on July 11. But by that time her journey had become a triumphant march. Volunteers flocked in to her and with the arms and ammunition she had brought from Holland she was accompanied by 2000 foot, well armed, 1000 horse, six pieces of cannon, two mortars, and 100 well filled wagons. Newcastle was her escort, Jermyn her Commander-in-Chief, and she herself, as she wrote exultantly to Charles, was her 'she majesty, generalissima' over all. Two days after leaving Stratford she met her husband and her two eldest sons at the foot of Edgehill. They slept that night at Sir Thomas Pope's house at Wroxton and the next day proceeded to Woodstock and thence to Oxford.

The welcome to Oxford was dubbed 'triumphant' and 'magnificent' with soldiers lining the streets, houses packed with spectators, trumpets sounding, heralds riding before her. At Carfax the town clerk read a speech and presented her with a purse of gold, at Christ Church the Vice Chancellor and the Heads of Houses in scarlet gowns welcomed her, students read verses in Latin and English, and she received the traditional University present of a pair of gloves. Charles then conducted her, by a private way through Merton Grove, to the Warden's Lodgings in Merton College which would be her home.[7]

With the Queen's arrival Oxford resembled even more the Court at Whitehall, with courtiers flitting between Christ Church and Merton, ladies dressing elegantly in spite of the cramped rooms in which they were compelled to make their toilets. Practical jokes were played on academics who were a natural butt, it was even possible to produce

a masque. But more serious was the renewal of the gossip and rivalry her presence brought. Digby, now one of her favourites, was at odds with Rupert; Holland, who had begun the war on the other side, came to Oxford to make his peace with her and spent far too long in her elegant drawing room at Merton, frequently in the afternoons when Charles himself was visiting his wife. Charles would not receive him back into favour and Holland departed for London and the Parliament. As he prepared for the coming campaign, Charles could have done without such distractions.

31—

The Second Campaign

By this time Charles and his Council of War had decided upon their general strategy and were preparing their main offensive for 1643. Newcastle would march south from Yorkshire, Sir Ralph Hopton would gain control in the south-west, while Charles himself would command in the centre. The task was not altogether easy. While Hull was in Parliament's hands, threatening their homes in the rear, Newcastle's progress was limited by the disinclination of his men to progress further south than Lincoln, and Cornishmen were similarly troubled at leaving Plymouth in enemy occupation while they marched through Devon. Charles in the centre had suffered a reverse when the Parliamentarians captured Reading on April 27. But victories at Landsdown and Roundway Down near Bristol on the 5th and 13th of July strengthened his position, while Rupert's capture of Bristol on July 26, two days after the Queen's arrival in Oxford, was of outstanding importance.

The direction of Charles's central thrust occasioned long deliberation in the Council of War. At last it was decided that he should take Gloucester in order to open up the Severn valley and ensure communication with Royalist support in South Wales. This meant abandoning an immediate push to London down the Thames valley, which might have been supported by a parallel drive by Prince Maurice through Hampshire and Sussex. But the western army was still occupied and Newcastle was still no further south than Lincoln. Moreover, it was felt that a threat to Gloucester would lure Essex away from the capital.

For the first time since his arrival in the city Charles left Oxford for a major campaign on Wednesday 10 August 1643. Gloucester did not immediately capitulate, though Essex, as predicted, began his march westward. Charles therefore, fearing to be cut off from his base and

hoping to turn the tables by preventing Essex's retreat to London, abandoned the siege. On September 20 the two armies came face to face at Newbury, with Charles barring Essex's route to the capital. The King was in command and he had been joined by Rupert. As at Edgehill the battle was indecisive but, unlike Edgehill, Charles drew off in the night leaving the way to London open to Essex, while he himself went north to Oxford. There were rumours that he had run out of ammunition, but if he had remained on the field it is likely that Essex would have retreated leaving the Royalists still barring his way to London. It was perhaps another lost opportunity for the King: he had neither taken Gloucester nor opened up a route to the capital nor prevented Essex from returning there. He had lost also his Secretary of State, one of the noblest of his subjects: for Falkland, who had never come to terms with civil war, had been seen to ride recklessly to his death in the battle. In appointing Lord Digby in Falkland's place Charles brought even closer to him than before a man who was deeply attached to his cause but who was impulsive and unreliable and, moreover, still hostile to Rupert, the most able of the King's commanders. Charles's first sally from Oxford, while not disastrous, had done him little good.