Two—

On Marriage Law and Ceremony

The Western conception of matrimony, like so much else in the development of Europe, evolved from a complex intermingling of Roman, Germanic, and Christian elements. As a result, marriage eventually came to be viewed from two perspectives so disparate as to seem almost antithetical to a modern person. On the one hand, based on such texts as Genesis 2:22–24, from which it was inferred that God himself had instituted marriage in the Garden of Eden, or Ephesians 5:31–32, the famous passage that compares the union of husband and wife to the marriage of Christ to the church, a Christian theology of marriage gradually evolved whose capstone was the inclusion of matrimony among the seven sacraments by theologians of the early scholastic period. Concurrently, beginning about 1100, and in marked contrast to the situation that prevailed during the early Middle Ages, the Latin church became the principal legislator on marriage and acquired jurisdiction over most marriage litigation, with the result that ecclesiastical authority in matrimonial matters was not generally challenged prior to the sixteenth century.[1] This fully developed medieval view of marriage as a sacral and ecclesiastical institution was, however, counterbalanced by an older secular and lay tradition that derived partly from barbarian custom but especially from ancient Roman survivals.

For centuries before and after the London double portrait most marriages were arranged, sometimes even before the couple had attained marriageable age, effectively subordinating the interests of the individual to more important social and economic considerations, sup-

plemented in the case of great families by diplomatic and dynastic concerns. For these same reasons, marriages were difficult to arrange and not everyone who wished to could marry, but for all who did the material conditions of adult life were determined in large measure by the terms of the marriage settlement. Only against the background of this development of European marriage as a social institution can both what is and what is not happening in Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini double portrait be understood.

European ideas about marriage were profoundly influenced by ancient Roman precedent. Because intent was the most basic principle of Roman law, the great jurisconsults of the second and third centuries logically held that marriage was concluded by the consent of the parties, and Ulpian's concise expression of this view, "Not cohabitation but consent makes a marriage," came to be included among the legal maxims of the final section of the Digest in Justinian's codification of the Roman law.[2] Roman lawyers termed this matrimonial consent affectio maritalis, or "conjugal affection," by which they meant, not some momentary expression of assent as part of a marriage rite, but rather a continuing mental state, shared by the partners. From a juridical point of view, this permanent emotive condition constituted the marriage. The Digest also envisioned marriage in ideal terms as a lifelong association of husband and wife for the procreation of legitimate children. But if affectio maritalis ceased to exist, the requisite legal consent no longer prevailed, and a divorce could easily be arranged.[3]

In a text that was to become a commonplace for later writers, Augustine gave a Christian twist to some of these ideas early in the fifth century when he enumerated the three "good things" about marriage as proles, fides, and sacramentum . The first, proles, or offspring, harmonized completely with Roman law on the purpose of marriage. What Augustine meant by fides —the marital fidelity of the spouses to one another—also conformed closely both with the idea of conjugal affection and with what fides implied in a legal context: the performance of one's duties as promised by an agreement. As for sacramentum, the word had as yet no theological connotations, and Augustine used it simply to refer to the couple's solemn mutual obligation that made their marriage indissoluble; on this matter Augustine's position represents a significant departure from Roman law, epitomizing a major difference between the legal traditions of Rome and the developing Christian view of marriage.[4]

By adopting the principle that marriage was concluded by the consent of the parties, Roman law established a clear legal distinction between concubinage and legitimate marriage. But there were other, less fortunate, consequences of this development, for henceforth no particular religious rites or civil formalities were necessary for contracting a valid

marriage, nor were any specific legal documents required.[5] To minimize possible ambiguity in these circumstances, various precautions were taken in the late Roman Empire to ensure adequate documentation of matrimonial consent, most commonly in the framework of the betrothal, which, as a result, came to displace nuptial rites in importance.

A betrothal in early Roman society was a simple mutual promise of future marriage, exchanged between the two fathers or between the bride's father and her future husband; sponsalia, the Latin word for "espousal," derived from the question-and-answer form this reciprocal promise took (the English cognate respond still retains something of the original meaning of the Latin root).[6] During the early imperial period, the Roman world adopted two Eastern betrothal practices that remained fundamental to the European conception of marriage long after Van Eyck's time. One of these was the redaction of the betrothal agreement in the presence of witnesses. The other was the custom of confirming the contract of future marriage with an earnest, usually at first a sum of money; to describe this security payment the Latin language appropriated and transmitted to medieval usage a loanword of Semitic origin, arrha .[7]

By the fourth century, the written betrothal agreement that created the bride's endowment—comprising both the dos, or dowry from her father, and the corresponding donatio ante nuptias, or prenuptial gift from her future husband—was often confirmed by ceremonies that in some parts of Europe eventually became part of the marriage ritual: an osculum, or kiss, and a ring placed on the fiancée's finger by the bridegroom. By a constitution of Constantine, for example, the betrothal kiss acquired juridical effect: if a man who had kissed his fiancée at the sponsalia died before the wedding, one-half of what had been agreed on as his prenuptial gift went to the woman, even though the marriage could not take place.[8] Concurrently, the betrothal ring was conflated with the arrha given as a guarantee that the betrothal agreement would be fulfilled, with the result that the bestowal of a ring in the context of a betrothal came to be called the subarrhatio of the bride.[9] But the real significance of both ceremonies was that by these actions the two parties to the proposed marriage were themselves directly involved in the sponsalia, as distinguished from the relatives or guardians who had arranged the marriage; by giving and receiving the kiss and the ring, the couple expressed publicly, in the presence of witnesses, their own intent to marry.

Although Roman and Germanic attitudes toward marriage differed, the greater importance Roman sponsalia assumed in late antiquity harmonized well with the emphasis placed on betrothal in barbarian law. Central to early Germanic marriage was the barbarian con-

cept of mundium . Although mundium in general was a man's dominion over his unarmed subordinates, this tutelage extended to the reproductive function of women, who were subject to exceptional taboos to protect the purity of the family blood (according to Burgundian law, for example, a woman who compromised a husband's mundium by leaving him was to be smothered in dung, and merely to touch a woman's hand was a punishable offense in Salic law).[10] The betrothal established the conditions for the transfer of the mundium over a woman to her husband, and the terms of the agreement between father and bridegroom to do this were more rigorously binding than the obligations of Roman sponsalia . The marriage ceremony by contrast was seen as no more than a traditio, or handing over of the bride to the groom, and the significance of the rite was further eclipsed because the matrimonial bond was juridically created by the subsequent consummation of the marriage. Thus what was most important in constituting a marriage for the Romans—the mutual consent of the spouses—was entirely lacking in barbarian society, where a daughter's mundium was for the father to bestow as he would. Conversely, what was of paramount concern to the Germans—the sexual union of the spouses—was of no juridical import to the Romans. Not surprisingly, these differences were to have long-standing consequences for European ideas about marriage.[11]

Another important element of Germanic betrothal was the constitution of the bride's dowry, for it was the dowry that legally distinguished a wife from a woman living in a less formal liaison. In Frankish law, for instance, the legitimacy of children depended on the proper dowering of their mother. Apparently this idea derived from Roman imperial legislation of the fifth century that required a dowry for legitimate marriage. Although that law was abrogated shortly after enactment, the notion that a dowry validated a marriage had meanwhile been adopted by the Germanic population settled within the empire. And the dowry agreement, often committed to writing—again under Roman influence—served to document in a particularly satisfactory way for a semiliterate society that a marriage had been contracted.[12]

When the barbarians appropriated the Latin word dos to describe the dowry, the meaning was inverted: whereas in Roman law the dos was given by the bride's family, in Germanic practice it became instead a marriage gift from the bridegroom. Payment was usually deferred until after the wedding night, when the husband—satisfied as to the bride's virginity and thus the integrity of her mundium —endowed his wife with what was often substantial property in the form of a Morgengabe, or "morning gift." Germanic influence on marriage customs was so pervasive that even among the Romanized population of western Europe

during the early Middle Ages, the wife's dowry as a gift from her husband largely replaced ancient Mediterranean practice. The dos as constituted by the bride's family did not again become the principal source of the wife's endowment until after the medieval revival of Roman law.[13]

The seventh-century Visigothic king Recceswinth helped to universalize the Germanic idea that a dowry was necessary for valid marriage. In revising an earlier law code, he added to the section on nuptial contracts the title "Let there be no marriage without a dowry." Subsequently this terse expression reappeared in a ninth-century collection of forged capitularies, and still later, the false claim was made that the formula was actually a canon of a church council that met at Arles in 524.[14] Thus provided with an authoritative, if spurious, pedigree, the principle that no marriage was valid without a dowry acquired ecclesiastical approbation and eventually, in the twelfth century, found its way into the mainstream of canon law when Gratian codified the pseudo-canon of Arles in the Decretum .[15]

A famous papal letter of 866 in which Nicholas I responded to inquiries from the Bulgarians, whose recently converted king was exploring the advantages of adhering to the Latin rather than the Greek form of his new religion, provides the most detailed early account of a developing Western rite for marriage. As described by the pope, a Roman marriage in the ninth century was contracted in two separate stages that effectively distinguished the secular from the sacred. First came the traditional civil formalities of the sponsalia, with the promise of future marriage requiring the consent of the couple as well as their parents. The pledging of the arrha followed as the bridegroom placed a ring on the fiancée's finger, and the dowry agreement in written form was presented to the bride before both parties' invited guests, who served as witnesses. The second stage was a religious rite that followed at some suitable later date, when the couple, in the pope's words, were brought "to the nuptial bond" ("ad nuptilia foedera"). This ceremony took place in a church and consisted of a eucharistic liturgy during which the nuptial blessing was bestowed (provided it was a first marriage) as a veil was held over the couple's heads. Following the service, the bride and groom left wearing crowns that were kept in the church especially for this purpose. The pope concludes by remarking that the religious ceremony was not, however, obligatory, for "according to the [Roman] law" only the parties' consent was required.[16]

The religious ceremonies Nicholas I described were further restricted in their application because the church in Rome reserved the nuptial blessing for those who were still incorrupti at the time of their wedding, a discipline that in turn explains the crowns, which were

Figure 6.

Sestertius of Antoninus Pius, 138–61. London,

British Museum.

Photo courtesy of the Trustees of the

British Museum.

symbols of virginity, as well as the blessing only of first marriages.[17] The predominantly secular character of marriage customs in ninth-century Rome, as described in the letter to the Bulgarians, is particularly striking, for the essential elements relate not to the ecclesiastical rite, although the pope himself speaks of this as creating the nuptial bond, but to the traditional legal formalities of sponsalia in Roman law.

The apparent dichotomy in the pope's views is not difficult to explain. Aside from the church's growing insistence on the indissolubility of a valid marriage, the secular and civil nature of marriage as an institution based on Roman law was already so firmly entrenched by the time of Nicholas I that it survived in modified form in various parts of Italy, including Rome, until the sixteenth century, although elsewhere in Europe quite different and essentially ecclesiastical marriage rites developed in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. These circumstances become directly relevant to the London double portrait on the presumption that the couple depicted by Van Eyck were of Italian descent.

Aside from the mention of the subarrhatio of the fiancée with a betrothal ring, the response of Nicholas I to the Bulgarians provides no information about hand gestures that may have accompanied Christian marriage ceremonies in the West prior to the year 1000. But from an early date Christians are presumed to have adopted the characteristic gesture associated with marriage in the ancient Mediterranean world, the symbolic joining of right hands that modern scholarship has called the dextrarum iunctio, although this expression is not found in any ancient or medieval text.[18] The Book of Tobit (7:15, according to the Vulgate text), in a passage that greatly influenced the evolution of European marriage rites, refers to a similar gesture when describing how Raguel presided over the marriage of his daughter Sarah to Tobias: "And taking the right hand of his daughter, he put it into the right hand of Tobias."

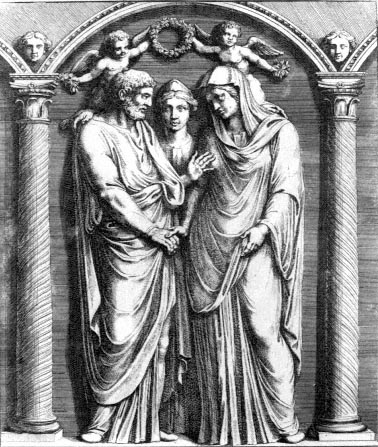

Figure 7.

Sarcophagus of a Roman general (detail), second half of the second century. Mantua, Palazzo Ducale.

Photo: Alinari/Art Resource, New York.

For pagan society in the Roman empire of the second century the dextrarum iunctio is conveniently documented by a sestertius of Antoninus Pius (Fig. 6) inscribed "Concordiae" and depicting a minuscule bridal couple joining right hands as they stand before an altar erected in front of colossal statues of the emperor and his wife, clasping hands in the same manner.[19] A closely related motif is found in Roman sarcophagal reliefs of the latter half of the second century and the early third in which a personified Concordia symbolically draws husband and wife together by placing her hands on their shoulders as the couple in turn join right hands (Figs. 7 and 8).[20] Because of the presence of attending allegorical figures, it is generally thought that such images were not intended as representations of actual rites. More likely, they were emblematic depictions of the married state, epitomizing the concor -

Figure 8.

Fragment of a Roman sarcophagus, c. 200. Rome, Palazzo Giustiniani.

Pietro Santi Bartoli, Admiranda romanarum antiquitatum ac veteris

sculpturae vestigia , Rome, 1693, plate 56. Ann Arbor, Special

Collections Library, University of Michigan.

dia, or harmony, between the spouses characteristic of an ideal marriage, and it is this idealizing element that made the imagery suitable for funerary monuments.[21]

Although a conflation of the Tobit text with the Roman dextrarum iunctio may have inspired the Roman mosaic of the fifth century in Santa Maria Maggiore representing the marriage of Moses and Sephora (Fig. 9), the bride's father in the mosaic does not actually bring the couple's hands together. Instead, like the personified Concordia of classical iconography, he uses an embracing gesture to unite the bridal pair. In contrast to the emblematic quality of images like Figures 7 and 8, the Moses and Sephora mosaic appears to have

Figure 9.

The Marriage of Moses and Sephora . Nave mosaic, 432–40. Rome, Santa Maria Maggiore.

Photo: Alinari/Art Resource, New York.

been intended as the representation of a marriage. The presence of guests supports this interpretation, and their separation by gender, with women accompanying the bride and men the groom, was destined to have a long history in the depiction of European marriage rites (cf. Plate 5). As the earliest Christian monument to depict such a scene, the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaic is thus evidently the prototype for the Christian iconography of this subject.

Astonishingly, there are no comparable images in Western art for many centuries thereafter. A few related Byzantine examples survive, most notably a pair of identical medallions (Fig. 10) on a Syrian gold marriage belt of the late sixth or early seventh century, now at Dumbarton Oaks, depicting the dextrarum iunctio of a husband and wife as Christ officiates between them, embracing the couple with his hands on their shoulders. The symbolism of these medallions apparently reflects the development of a popular religious ritual for Christian marriage much earlier in the East than in the West, and although the "Concord" of the Greek inscription implies an element of continuity with the coin type of Antoninus Pius, it is now God who is the source of concord in marriage, as the inscription explicitly

Figure 10.

Medallion from a Byzantine gold marriage belt, Syria, late sixth or seventh century.

Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Collection.

Photo copyright 1992, Byzantine Visual Resources, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

states: "From God, Concord."[22] The disappearance in the West, for the better part of a millennium, of both visual and textual references to a matrimonial joining of right hands strongly suggests that the gesture may have fallen into disuse by late antiquity.[23] A famous spurious text, wrongly ascribed to Augustine, moreover, refers to the marital consent being given "by the heart and mouth," and "not by the clasp of a hand."[24]

In early Frankish Gaul the customary place for blessing a marriage was not a church but the nuptial chamber as the bridal couple prepared to retire on the night of the wedding, and the Roman stricture that only virgins could receive the nuptial blessing was not rigorously applied.[25] Perhaps these different circumstances explain why the earliest attempts in the West to require the blessing of all Christian marriages are found in Frankish lands under Carolingian control, as, for example, in Charlemagne's capitulary of 802.[26] It was, in fact, among the Franks that the basic elements of the new ecclesiastical model for marriage first

appeared during the century that preceded Nicholas I's Bulgarian letter, with its continued emphasis on the older civil model. These developments can be traced in legislation that originated with the Carolingians themselves, as well as in other contemporary documents, including various spurious papal letters in the Pseudo-Isidorian forgeries of the mid-ninth century. The texts involved aimed particularly at prohibiting clandestine marriage, and the most important were later codified in the Decretum of Gratian, making them part of the living tradition of Western canon law in the time of Van Eyck.

In addition to the standard betrothal formalities of Roman and barbarian law, legitimate marriages were now also to be marked by public celebration and a priestly blessing. To deal with the vexing problem of impediments to a valid marriage, usually because the couple were too closely related according to ideas about consanguinity that developed during the eighth century, one of these texts prescribes an inquiry into such relationships prior to the betrothal by local people assembled in a church with the priest presiding. Yet another religious element, known as the "nights of Tobias" because it was derived from the biblical account of the marriage of Tobias and Sarah, was introduced into the celebration of marriage during Carolingian times. Newlyweds were counseled, out of respect for the nuptial blessing, to defer the consummation of their marriage for three nights, or at least until after the wedding night, devoting themselves instead to prayer.[27]

In northern France at the turn of the eleventh century these diverse elements coalesced into the earliest form of what was to become the traditional Western marriage rite. In the process a remarkable change occurred, as the civil betrothal formalities associated with contracting a valid marriage according to Roman law since late antiquity were incorporated into a new ecclesiastical rite celebrated at the church door just before the nuptial liturgy of the older Roman tradition (transmitted north of the Alps when the Roman liturgical books were adopted by the Carolingians). And it was this new preliminary rite, rather than the Roman nuptial mass, that eventually came to constitute for both canonists and theologians the essential element of marriage as a sacrament.

According to the Anglo-Norman service books from the first part of the twelfth century that provide the earliest firm evidence for the details of the new ecclesiastical ceremony, the priest met the bridal party and their guests at the door of the church. Following inquiries about possible canonical impediments to their union, the priest verified the couple's consent to be married, and in conformity with the principle taken over from barbarian customary law that there could be no valid marriage without a dowry, either this marriage gift from the groom was paid or the terms of the dowry settlement were read aloud. And what

formerly had been a betrothal ring given as a pledge, or arrha, that the promise of future marriage would be fulfilled now became a wedding ring, blessed by the priest and ceremoniously placed on the bride's hand by the groom with the priest's assistance. There is no reference in these rituals to additional hand gestures. The church-door ceremony concluded with the priest's blessing. Then the bride and groom, carrying lighted candles, followed the priest into the church for the nuptial mass of the Roman marriage rite, when further prayers were pronounced over them.[28]

The earliest rubrics for the new rite refer to the site of the ceremony with such phrases as "before the church entrance" or "at the doors of the church." But the preferred expression soon became in facie ecclesiae, that is, "in the face of the church," which was interpreted metaphorically, not as a building but as the local Christian community.[29] Thus from the twelfth century onward the church-door wedding rite was thought of as an intrinsically public ceremony, in marked contrast to secret or clandestine marriage.[30] In this sense the new rite helped to realize an ideal embodied in the earliest known Western ecclesiastical legislation that specifically concerned the ritual of Christian marriage, a canon of the Frankish national synod of Verneuil in 755 that enjoined all persons, "noble as well as ignoble," to celebrate their nuptials publicly.[31]

A man and woman in the fifteenth century could indeed contract a valid marriage "in complete solitude," as Panofsky argued, or privately before witnesses, as in his interpretation of the Arnolfini double portrait. But it is not the case that such a marriage was "legitimate," as he and his many followers have also claimed. Marriages contracted secretly rather than in a public rite, which in northern Europe normally entailed the presence of a priest, were in fact considered illicit. Using terminology that is just the opposite of Panofsky's characterization, canon law texts routinely describe clandestine marriage as "non legitimum," and secret marriages were strictly forbidden for centuries prior to the London double portrait.

When compiling the Decretum around 1140, Gratian brought together a number of these earlier texts that stressed the public character of legitimate marriage and condemned marriages that were clandestine, including the pseudo-canon of Arles and excerpts from Nicholas I's response to the Bulgarians. Especially important were two letters ascribed to early popes with which the chapter on clandestine marriage begins (both are actually false decretals, but their authenticity was not questioned until long after Van Eyck's time). The first letter catalogues the conditions necessary for legitimate marriage, including sponsalia,

a dowry settlement, the blessing of a priest, and the couple's observation of the customary "nights of Tobias"; this anonymous writer goes on to say that clandestine marriages were to be presumed "adultery, concubinage, debauchery, or fornication, rather than legitima conubia ." The second letter states categorically: "No Christian of whatsoever condition shall enter into a marriage secretly, but having received the blessing from a priest, he shall marry publicly in the Lord."[32]

Gratian concluded that since clandestine marriage was universally forbidden by his sources, such marriages were "infected," or tainted with moral corruption. Elsewhere in the Decretum he drew what remained until after the Council of Trent the standard canonical distinction between a "legitimate" marriage, celebrated according to law and local custom and characterized by public rites such as the constitution of the bride's dowry and the priest's blessing, and a clandestine marriage, which because these formalities had been omitted was "not legitimate." But since the Decretum had also codified Nicholas I's opinion that the couple's consent alone created a marriage, Gratian was forced to recognize that a clandestine marriage was nonetheless still a valid one.[33] The importance of Gratian's Decretum for understanding the Arnolfini double portrait is that this authoritative textbook of the new canon law firmly established that clandestine marriage was always illicit and at the same time greatly enhanced the priest's blessing as a constituent of legitimate marriage over the secondary role it had had for Nicholas I in the Bulgarian response.

Gratian's Decretum is a typical monument of the fervid intellectual activity, particularly in law and theology, that characterizes twelfth-century Europe. Within this framework the classic doctrine of the medieval Latin church on matrimony was hammered out during the latter part of the twelfth century and the first years of the thirteenth, as differing opinions were subjected to discussion and criticism by canonists, theologians, and popes. The central issue was whether the marriage bond was created by the consent of the parties, as in the Roman law, or by the consummation of the marriage, as in the Germanic tradition, a dispute that ended with a definitive victory for the consensualists early in the thirteenth century during the pontificate of Innocent III. There was, however, a significant difference between Roman and canon law with regard to matrimonial consent: whereas the Roman law required the consent of the parents as well as the spouses, in the fully developed medieval canon law parental consent was not necessary.[34] Under the same pope, the church's position on consanguinity as an impediment to marriage was greatly relaxed when the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 reduced the prohibited degree of relationship from the

seventh to the fourth: thus while formerly persons with a common ancestor as remote as the seventh generation (that is, sixth cousins) could not marry, under the new legislation the prohibition extended only through the fourth generation (or, third cousins).[35]

A further canon of the Fourth Lateran Council contains Innocent III's forceful statement: "Following in the footsteps of our predecessors [the allusion is to the pseudo-papal letters codified in the Decretum and cited above], we utterly prohibit clandestine marriages." The canon continues with a series of regulations aimed at preventing clandestine marriage within the prohibited degrees, including the requirement that the bans of marriage be published in the church so as to bring impediments to light, as well as a provision that denies legitimacy to children born of a clandestine marriage where there was an impediment due to consanguinity.[36]

Ecclesiastical objection to clandestine marriage was thus motivated by two considerations. The first concerned unions deemed incestuous, which were often initiated by clandestine marriage: such unions were to be discouraged by the enforcement of the more reasonable consanguinity standards of the Fourth Lateran Council. A second, pastoral, consideration stemmed from the premise that sexual intercourse outside marriage was morally wrong. Because it was frequently uncertain whether persons contracting marriage in secret were really married, from the clerical point of view couples so joined might well live out their entire lives in a continuing state of fornication or—if they later contracted a second marriage when the first was actually binding—adultery.

Although the legislation enacted by the Lateran Council became the public law of the entire Latin church, it marked neither the beginning nor the end of clerical efforts to cope with clandestine marriage. Indeed, from the late twelfth to the early fourteenth century, provincial councils throughout Europe enacted statutes severely penalizing those who entered into marriage secretly; these statutes remained in effect regionally until the same legislative bodies, acting centuries later on a decree of the Council of Trent, invalidated such marriages. Although some penalties were more colorful, the most common was excommunication, the severest punishment the church could inflict.[37] As for the context of the London double portrait, prior to 1559 Bruges and Ghent were part of the diocese of Tournai, a suffragan in turn of the archdiocese of Reims, and the law on clandestine marriage for this ecclesiastical province (which included most of the northern territories of the duke of Burgundy) was established by a provincial council of 1304. The relevant canon provides that "each and every" person of the province who either enters into a clandestine marriage, in any way arranges one, or is merely present at one is to be excommunicated ipso facto and denied the right of Christian burial.[38]

Thomas Aquinas sums up the church's doctrine succinctly by saying that if the parties give their consent and there is no impediment to the union, a clandestine marriage is valid but also sinful as well as dishonorable, since often at least one of the parties is guilty of fraud. Similar views are expressed by many later writers, including Van Eyck's contemporary Saint Antoninus of Florence, who observes pointedly that "those who contract marriage clandestinely, sin mortally."[39] And ordinary people evidently held similar views on clandestine marriage: the offspring of such unions were thought likely to be "blind, lame, hunchbacked, and dim-sighted."[40] Lay society in large measure supported the church's new role as arbiter of European marriage law for the simple reason that from the twelfth century on a major concern of both the feudal aristocracy and the rapidly developing middle class was the secure transfer of property and wealth through heredity to legitimate heirs.[41] Because the church now made the rules, only the ecclesiastical establishment could determine which marriages were canonically contracted and consequently which heirs were legitimate. If clandestine marriage is understood within this general framework, the horrendous social and legal disabilities that might follow from such a union are obvious.

Nonetheless, despite the obstacles, men and women continued to marry in secret. It is evident from papal registers of the late fourteenth and the early fifteenth century that some clandestine marriages were intentionally contracted by upper-class couples who were related within the forbidden degrees and for whom a public and ecclesiastically approved wedding was therefore impossible. In such cases papal letters could be subsequently sought to lift the ban of excommunication and to request a dispensation from the impediment. As long as the relationship was not too close, such petitions were usually granted with a specific provision legitimizing all offspring of the union, past as well as future, and—after an appropriate penance had been imposed on the couple—the marriage was publicly solemnized.[42]

Clandestine marriage was sometimes resorted to as the only practical way for children to escape from unsatisfactory marriage alliances arranged by their parents, particularly in the case of girls, who even in great families were sometimes subjected to what today would be considered shocking instances of child abuse to force them into submission. Clandestine marriage also opened the way for the marriage of couples who could never hope for parental approval of their union. The Paston Letters provide a well-known example. In 1469 Margery Paston, a daughter of this famous Norfolk family, made a clandestine marriage with the Pastons' chief bailiff, Richard Calle. Both the family and the bishop of Norwich were appalled by her action, but there was nothing they could do about it, and Margery's mother wrote shortly thereafter to her son that "we have lost of her but a worthless per-

son."[43] Almost exactly contemporaneous with the Arnolfini double portrait was the tragic clandestine marriage of the future Albrecht III, son of Duke Ernst of Bavaria-Munich, to Agnes Bernauer, a barber's daughter and attendant in an Augsburg bathhouse, where Albrecht first met her. Fearing for the future legitimacy of his line, the duke dealt with the situation decisively. Distracting his son's attention with a tournament, he had Agnes seized, tried for witchcraft, and, in October 1435—the year after the completion of the London panel—thrown into the Danube near Straubing, where her tomb may be seen to this day in a chapel the duke endowed in the Carmelite church as expiation for his sin.[44]

Further instructive examples of clandestine marriage are found in Boccaccio's Decameron . The most delightful is Pampinea's story for the second day (2.3). A young Florentine merchant named Alessandro, returning to Italy from London, upon leaving Bruges falls in with the retinue of a youthful abbot traveling to Rome. One night Alessandro and the abbot are forced to share the same room, and it turns out that the abbot is really a beautiful young woman in disguise. When the two are alone, the woman reveals her passionate love for Alessandro, who accepts her offer of clandestine marriage before they spend the night together. The following day they continue their journey as if nothing had happened, but when the travelers reach Rome, the "abbot" confesses to the pope both her clandestine marriage to Alessandro and her true identity as a daughter of the king of England, in flight from a marriage her father had arranged with the aged king of Scotland. Amazed that a king's daughter would choose such a husband but realizing "there was no turning back," the pope, in the presence of the cardinals and a large concourse of important persons, "had them go through the marriage ceremony solemnly from the beginning, and after splendid and magnificent nuptials had been celebrated, he dismissed them with his blessing." The passage quoted is particularly important, because it indicates—and canon law texts corroborate—that a clandestine marriage was formalized later by a public ecclesiastical ceremony, for as a gloss to the Decretales of Gregory IX explains, "the first marriage has taken effect before God but not before the church."[45]

The reputation of clandestine marriage was further darkened by rakes and profligates who used it as a convenient and seemingly reliable technique for seduction. Just how notorious clandestine marriage had become by the later Middle Ages when used for such ends may be judged from a remark of Aquinas. "According to some," Thomas says, "if in such a case the woman is markedly inferior in social status to the man, he has no further obligation toward her, since it may be presumed as probable that she was not deceived, but merely pretended to be."[46] The use of clandestine marriage as an instrument of seduction,

especially across class lines, was still well understood at the end of the eighteenth century, for the inherent comic possibilities of the situation are skillfully exploited in Mozart's Don Giovanni, when the Don proposes such a marriage to Zerlina in attempting to add Masetto's fiancée to the catalogue of his conquests.[47] And it is almost certainly this disreputable aspect of clandestine marriage that accounts for the interpretation of the London double portrait in the Spanish inventory of 1700 as a genre picture representing a couple's mutual deception of one another as they surreptitiously "seem to be getting married at night."

The chance survival of a register of sentences handed down by the officiality, or episcopal court, of the bishop of Cambrai in Brussels between 1448 and 1459 permits a glimpse of the realities of clandestine marriage from a judicial perspective at approximately the same time and place the Arnolfini double portrait was painted. A majority of the 1,590 sentences rendered by the two judges who consecutively presided over this ecclesiastical tribunal during the eleven years covered by the register dealt with matrimonial litigation, and of these, 20 involved instances of clandestine marriage.[48] Before several representative cases are summarized, a few legal technicalities need to be mentioned. A marriage was accounted clandestine in canon law either because it had been contracted secretly—that is, without witnesses or without publication of the bans of matrimony as required by the Fourth Lateran Council—or because it had not been publicly solemnized, a ceremony that in northern Europe normally required the presence of a priest. A betrothal, however, might also be publicly celebrated before a priest; for this and other reasons that will be discussed more fully in the next chapter, canonists and theologians from the twelfth century on distinguished a betrothal from a wedding according to the tense used in expressing the consent to be married: the words of consent in the future tense, or verba de futuro, that characterized a betrothal were no more than a promise of future marriage, whereas words of consent in the present tense, or verba de praesenti, created the indissoluble marriage bond. Words of future consent followed by sexual union were held to constitute consent in the present tense, and a presumptive marriage was the result.

The documentation in the Brussels Liber sententiarum suggests that truly secret marriages were rare, since witnesses were present in all but one case. In another instance the ceremony actually took place in a church before a priest. Celebrated very early on the morning of 15 February 1451 in the parish church of Lier in the presence of a priest who was the precentor of a major church in Malines, the marriage of Elisabeth de Ymersele and Godefroid Vilain was clandestine only because the bans had not been published and the priest acted without proper authorization. Yet when the case came before the Brussels tribunal, in con-

formity with the legislation of the Fourth Lateran Council,[49] the priest was suspended from his priestly functions for three years and ordered to pay various fines, including one for lifting the penalty of the excommunication he had automatically incurred by taking part in the ceremony. Because both bride and groom are described as "nobiles personae," this clandestine marriage, arranged with the complicity of a locally prominent priest, was probably the consequence of strong parental opposition; a clandestine church wedding in such a case presented the family with a fait accompli they had to accept.[50]

Seven of the clandestine marriages documented in the register took place in Reimerswaal on an island of the same name in South Beveland (neither the island, absorbed in the process of land reclamation, nor the town, destroyed by inundation in the sixteenth century, exists today). The journey there from the Brussels region was long and arduous, obliging a couple to travel via Antwerp to Bergen op Zoom in North Brabant (in the diocese of Utrecht, beyond the jurisdiction of the bishop of Cambrai) and thence by water into the Zeeland archipelago. Reimerswaal was thus evidently a favored place for clandestine marriage, with the ceremonies, as mentioned in the register, taking place variously in an inn or a chapel. The case of Elisabeth Winrix and Gilles de Ghesterle is fairly typical. Because the bride's family objected to the marriage, the couple eloped to Reimerswaal to be married clandestinely. When the case was brought before the officiality after they had returned home, all the judge could do was to sentence the couple to solemnize their marriage.[51]

The Brussels register also documents the use of clandestine marriage to circumvent known or perceived canonical impediments to a marriage as well as to escape from an unsatisfactory marriage parents sought to impose. But the reason in fourteen of the twenty instances of clandestine marriage was the couple's hope that by entering into an illicit marriage, they might find a way out of an earlier matrimonial entanglement. Catherine Boene, for example, had at first been publicly betrothed to Gommar Naghel. The bans of marriage were duly published, after which the couple held a wedding celebration, but they failed to solemnize their marriage before the festivities. Subsequently, but in a different locality, Catherine publicly contracted a second betrothal, this time to a certain Hendrik van der Velde. The bans were again published, but the marriage was not solemnized, as the couple eloped instead to Reimerswaal for a clandestine ceremony. When the case came before the bishop's court, the judge dissolved the betrothal of Catherine to Gommar, who was awarded as an indemnity four gold florins and half the money he and Catherine had received on their "wedding" day (the other half had been used to pay for the marriage festivities), while Catherine and Hendrik were directed to solemnize their clandestine mar-

riage and to undertake a pilgrimage to Cologne as a moral recompense for the injury done to the unfortunate Gommar.

A second case is of the same general type. Gerard van der Elst exchanged words of future consent with Gertrude Gheerst, but because sexual intercourse followed the betrothal, a presumptive marriage was the result. After five children had been born of his union with Gertrude, Gerard contracted marriage clandestinely with one Margaret Abs at Reimerswaal, with a child subsequently being born of this second union. At a judicial hearing in Brussels it was decided that Gerard should solemnize his presumptive marriage with Gertrude since that took chronological precedence over the clandestine marriage with Margaret at Reimerswaal. But before the sentence was actually promulgated, Gertrude Gheerst took her revenge by also journeying to Reimerswaal, where she clandestinely exchanged words of present consent with one Baudouin van Vorspoel. In the end the clandestine rites in Reimerswaal proved of no avail to either party, for in his final disposition of the affair the judge merely reiterated his earlier decision that Gerard and Gertrude were to solemnize their long-standing presumptive marriage.[52]

It seems reasonable to condude from the foregoing discussion that the staid, formidable man of mature age depicted in the London double portrait—presumably the wealthy and aristocratic Lucchese merchant Giovanni Arnolfini—is not a likely candidate for an adventure in clandestine matrimony, a category of human experience completely at variance with the social and psychological mentalities the picture embodies, to say nothing of the legal complications for a family of means that might follow from the doubtful legitimacy of children born of such a union. Nor is it really conceivable that a successful and astute businessman would commission from Van Eyck a picture to commemorate a marriage strictly forbidden by the church and considered mortally sinful by contemporary moralists, a marriage that would have to be formalized later by a public ecclesiastical ceremony, and for which he, his wife, the duke of Burgundy's painter, and the other witness as well would incur ipso facto excommunication and be deprived of their right to Christian burial. And it is surely unlikely that Jan van Eyck would willingly have accepted a commission with such unpleasant liabilities attached.

Thus the historical context argues against the London double portrait as representing a clandestine wedding. Indeed, when the problematic and much discussed hand and arm gestures in the picture are contrasted with what is known of marriage ceremonies in the Burgundian Netherlands of Van Eyck's time, it becomes apparent that the picture cannot depict a wedding in any form, for what the artist has shown bears no resemblance to these rites.

Symbolic matrimonial gestures linking the spouses' hands, evidently unknown in the West in the time of Nicholas I, seem to have developed as part of the new marriage rite in facie ecclesiae and within the framework of a new sacramental theology that evolved during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Contemporary discussion among canonists and theologians of how the marriage bond was formed also contributed to this development. Once the word sacramentum, as used in biblical and patristic texts on marriage, had been dialectically analyzed, matrimony began to be definitively categorized as one of the seven sacraments, especially with the Sentences of Peter Lombard, completed in the 1160s.[53] But contrary views continued to be expressed well into the thirteenth century, in part because the financial arrangements associated with marriage smacked to some of simony.[54] Concurrently, as the classic Augustinian definition of a sacrament as "a visible sign of invisible grace" came under the influence of Aristotelian concepts about matter and form, speculation arose as to which "sensible signs" (that is, things that can be experienced or understood through the senses) constituted the form of the various sacraments, and these "sensible signs" were then viewed as the operative instruments by which sacramental grace was conferred.[55]

In the case of matrimony, the speculative phase was especially protracted, as lawyers and theologians offered differing ideas as to the ceremonial significance of nuptial rites. Not surprisingly, some theologians at first emphasized the nuptial blessing of the ancient Roman liturgy because in their view this priestly blessing was the "sensible sign" of the sacrament, a position still supported by William of Auvergne, an early master of theology at Paris and bishop of the city from 1228 until his death in 1249.[56] Other writers, adopting a juridical perspective, argued instead that the traditio —whether understood as the handing over of the bride to the groom or as the mutual giving of the spouses to one another—was the central ceremony of the rite because by this action the marriage was constituted.[57] These earlier opinions were gradually displaced as theological and legal opinion crystallized around the Roman law principle that marriage was contracted solely by the consent of the parties, with the result that the words or other "equivalent signs" expressing the mutual consent came to be considered the form of the sacrament of matrimony as well as what created the marriage bond joining the couple for life.[58] Points of disagreement nonetheless remained. According to a rigorist view advanced by Duns Scotus at the beginning of the fourteenth century, for example, and long supported by Scotist theologians, the form of the sacrament of matrimony consisted of "audible words," and thus, although persons such

as deaf-mutes who were unable to exchange words of consent could contract marriage using equivalent signs, they did not, in Scotus's view, receive the sacrament of matrimony.[59]

The development of European rites for marriage reflects these intellectual currents. Beginning in the latter part of the twelfth century, the liturgical documentation for marriage rites gradually becomes more abundant as the number of surviving texts increases and the rubrics for the ceremonies become more explicit. The evidence is nonetheless fragmentary until after the Council of Trent, for service books with a marriage ordo are still relatively rare as late as the early sixteenth century. Marriage rites also continued to develop throughout this period and were subject to wide regional variation. Yet despite these differences, local forms of the new ceremony at the church door often evolved from a common prototype, the marriage of Raguel's daughter Sarah to Tobias, according to the Vulgate version: "And taking the right hand of his daughter, he put it ['tradidit'] into the right hand of Tobias saying: The God of Abraham and the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob be with you, and may he himself join you together and bless you abundantly" (Tobit 7:15).

In early rituals for marriage "in the face of the church" the hand gesture remains a traditio gesture, precisely as in the Tobit text, as the father, by placing his daughter's hand into the hand of the groom, transfers his tutelage of the woman to her husband. But this gesture was not the ancient dextrarum iunctio, because there was no real joining of hands, and the rubrics do not mention that the right hands were used, apparently considering the issue unimportant, despite the specificity of the biblical description of the marriage of Tobias. By the traditio the father did no more than "give the bride away," as is sometimes still said in the English-speaking world. Gradually the ceremony was clericalized, with the priest displacing the father and assuming Raguel's role in giving the bride's hand to the groom, although at first there is no mention that right hands were to be used. This definitive hand gesture as part of the consent rite becomes common only in the fourteenth century, when the rubrics in extant service books first refer to the joining of right hands.[60] The hand gesture then also took on new significance, symbolizing the accompanying exchange of the words of consent, which were couched either as questions addressed to the spouses by the priest—"Will you have this woman for your wedded wife?"—or as a formula repeated by the bride and groom after the priest: "I, N. , take you, N. , to be my wedded husband." With the couple usually still joining their right hands, the priest then concluded what had become the essential part of the sacramental rite with a liturgical formula either patterned directly on Raguel's words or expressed in a more declaratory form, with phrases like "I

marry you in the face of the church" or "What God has joined together, let no man put asunder." In many rituals a blessing of the couple's joined hands followed at this point.[61]

Thus in northern Europe from the fourteenth century on, the joining of the right hands had a composite meaning: not only did it give visual expression to consent in the present tense, but—because the phrasing of the accompanying words of consent involved the idea of a mutual traditio of the spouses and because the joining was frequently followed by a sacerdotal blessing independent of the older benediction given during the Roman nuptial mass—it also epitomized in a single gesture the various theories of what constituted the form of the sacrament of matrimony. The ring ceremony sometimes preceded and sometimes followed the exchange of the words of consent accompanied by the joining of hands; in either case its significance for the transalpine ecclesiastical rite of marriage "in the face of the church" was decidedly secondary.

A very different situation prevailed in those parts of Italy where the older traditions described by Nicholas I were not displaced until after the Council of Trent, when the Rituale romanum of Paul V made the northern European rite "in the face of the church" normative in the Latin church. Because this archaic Italian marriage ceremony was often presided over by a notary and commonly took place in the house of the bride's father, it might seem at first that this is precisely what the London double portrait depicts, but as will be explained in the next chapter, any apparent similarities are superficial and coincidental. What needs to be stressed here is that when marriage was contracted according to this rite—whether in a domestic or an ecclesiastical setting, whether before a notary or before a priest—there was no joining of the couple's hands but only the giving of a ring by the groom to the bride, without ceremony and without words, after the consent had been verified by the presiding individual.

This regional difference in the characteristic marriage gesture is exemplified by the way artists represented the marriage of the Virgin. A fragment of a Michael Pacher altarpiece in Vienna (Plate 2) depicts the fully developed northern hand-joining rite as Zacharias, in contemporary pontifical vestments, bestows the concluding blessing.[62] In northern works the high priest often assists even more actively in this conventional joining of right hands by actually bringing the hands together, as in Dürer's print in the Marienleben cycle or in Van Meckenem's engraving of the same subject (see Fig. 50). Similarly, in Italian works the priest frequently intervenes directly, grasping the wrist or forearm of bride or groom or of both so as to guide the couple's hands together, but his purpose is not, as in northern art, to effect the joining of right hands, but to facilitate the bestowal of the ring. This ceremo-

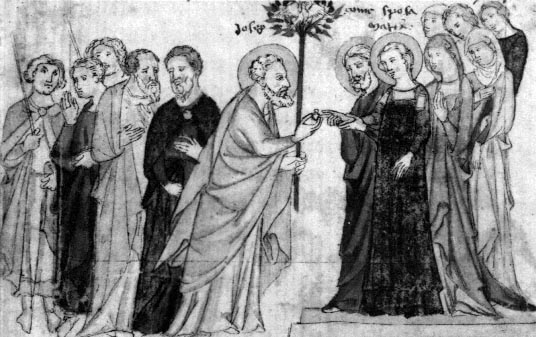

Figure 11.

The Marriage of the Virgin . Italian translation of the Meditationes vitae Christi , fourteenth century.

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, ms. ital. 115, fol. 9r.

Photo: Bib. Nat. Paris.

nious intervention of the priest can be seen with particular clarity in a fourteenth-century drawing from the earliest illustrated manuscript of the Meditationes vitae Christi (Fig. II), where the presentation of the Virgin's hand by Zacharias for Joseph's imposition of the ring is still akin to the earlier traditio gesture. Although Italian painters commonly show the ring being placed on the Virgin's right hand—as in Giotto's Arena Chapel fresco, Raphael's Sposalizio, and Sienese art in general (see Plate 8)—in Florentine works, as exemplified by Fra Angelico's panels in the Prado and the Museo di San Marco or by Ghirlandaio's fresco in the Santa Maria Novella cycle (Plate 3), it is invariably the left hand that receives the ring.[63]

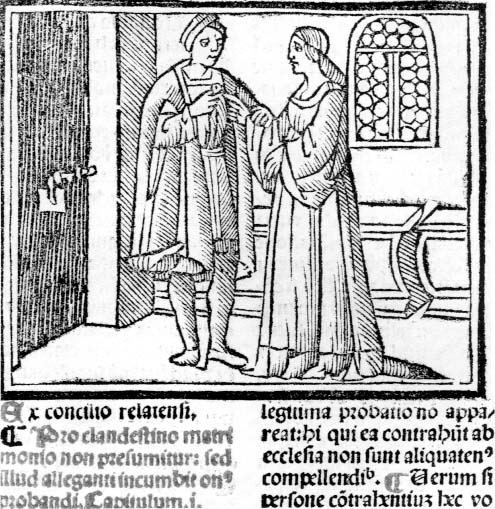

An even more inclusive example of the Italian practice of depicting a ring ceremony rather than the northern hand-joining rite is provided by a richly illustrated Venetian edition of the three-volume corpus of medieval canon law published by Lucantonio Giunta in 1514.[64] Without exception, the thirty-odd woodcuts in this work that illustrate marriage rites center on the bestowal of rings and include such diverse representations as a solemn

Figure 12.

Clandestine marriage. Decretales of Gregory IX, Venice, 1514, fol. 399v.

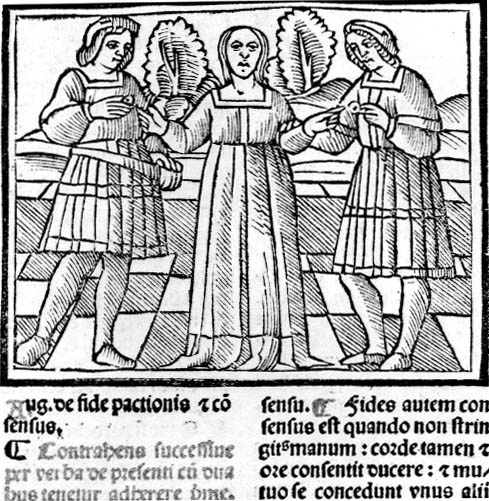

marriage ceremony before a bishop (see Fig. 25); an illustration of clandestine marriage (Fig. 12) in which a man is about to place a ring on a woman's finger as they stand alone in a room behind a closed and bolted door; and an emblematic image (Fig. 13) intended to illustrate the case of a woman successively married de praesenti to two men, each of whom is portrayed in the process of placing a ring on her finger,

The evidence thus indicates that the Western matrimonial joining of right hands was not a survival, or even a revival, of the dextrarum iunctio as has generally been assumed since the nineteenth century, for if this ancient matrimonial gesture had survived anywhere, one might reasonably expect to find it in the Italian peninsula. Although it apparently origi-

Figure 13.

Successive marriage to two men. Decretales of Gregory IX, Venice, 1514, fol. 400v.

nated in the traditio, or transfer of the bride from the guardianship of her father to that of her husband, the linking of right hands was in fact a new symbolic gesture that arose in transalpine Europe during the final stage of the development of the marriage ritual "in the face of the church"; and it signified not so much concordia (as the ancient gesture did) as the mutual consent of the spouses that had become, in scholastic terminology, the essential form of the sacrament of matrimony.[65]

The iconography of marriage evolved in tandem with the theological and ceremonial developments outlined above. At the end of the tenth century the subject reappears in Western art for the first time in many centuries with a representation from the Reichenau

Figure 14.

The Marriage of the Virgin . Gospels of Otto III, Reichenau,

c. 1000. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 4453, fol. 28r.

Figure 15.

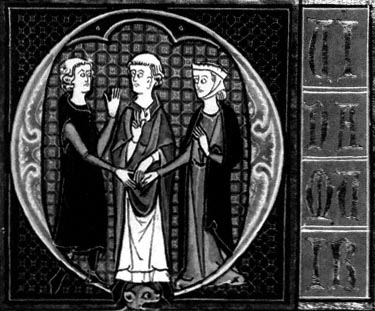

Nuptial blessing beneath a veil. Gratian, Decretum , French,

fourteenth century. Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica

Vaticana, ms. lat. 1370, fol. 247v.

Figure 16.

The Marriage of David and Michal . English Psalter, c. 1310. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek,

Cod. gall. 16; fol. 35v.

school of the marriage of the Virgin in the Gospels of Otto III (Fig. 14); halfa century later the same composition was repeated in the Bernulfus Gospels, also produced at Reichenau and now in Utrecht (Plate 4).[66] The officiating priest presides over a traditio ceremony in which Mary is given to Joseph, but the imagery is derived from neither the dextrarum iunctio of antiquity nor the biblical description of the marriage of Tobias. Instead the Virgin's hands, joined palm against palm, are enclosed within Joseph's extended hands, replicating the characteristic medieval immixtio manuum gesture with which a feudal lord received the fealty of a vassal.[67] Into the fourteenth century, miniatures occasionally depict the Roman nuptial blessing of the bridal pair beneath a veil (Fig. 15),[68] perhaps reflecting a continuing currency of the view that this was the essential element in the marriage rite. An illumination in an English psalter of the early fourteenth century (Fig. 16), however, still conceptualizes the marriage of David and Michal partly as a traditio based on the Tobit text

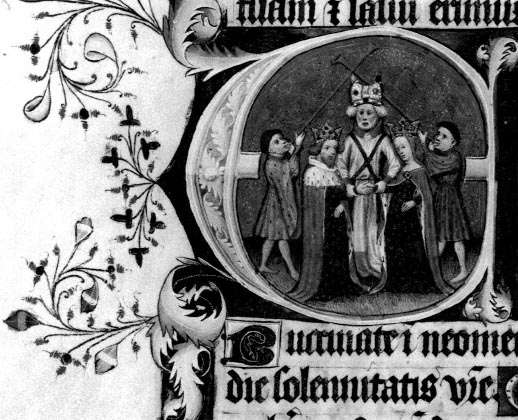

Figure 17.

Marriage scene. Gratian, Decretum French, fourteenth century. Vatican

City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, ms. lat. 2491, fol. 478r.

(although Saul holds Michal by her left rather than her right hand), but the ritual transfer of the bride here is subordinate to the more important joining of the couple's right hands that accompanies the words of consent spoken by David.

Panofsky sought to relate this very miniature to the "Arnolfini Wedding," claiming the raised left forearm of David exemplified the same gesture as that of the male figure in the London double portrait.[69] The psalter illumination in fact has its true parallel in similar French and English miniatures of the early fourteenth century depicting a couple with their hands joined in the new marriage gesture of consent, usually in the presence of a priest, as one or both raise their other hand in this way (Fig. 17).[70] The gesture is unrelated to the London double portrait for it indicates speech and is meant to convey the idea that the words of consent are being spoken as the hands are joined. Internal evidence in manuscript psalters helps substantiate this. The miniature in Figure 16 illustrates Vulgate Psalm 38, whose text has nothing to do with marriage, but just as the descriptive title over the illuminated letter, "Saul has given David his daughter Michal as wife" ("Saul dedit David Michol filiam suam in uxorem"), provides an explanation for the miniature below, so the

Figure 18.

The Marriage of David and Michal . Psalter and Hours of John, duke of Bedford, 1420s. London,

British Library, Add. ms. 42131, fol. 151v.

Photo by permission of the British Library.

verse directly beneath the historiated initial, "I spoke with my tongue" ("Locutus sum in lingua mea"), has been exploited as a caption justifying the marriage scene above as an illustration for this particular psalm.

Reflecting what appears to be a common tradition of psalter illumination, the same approach is found a century later in another English manuscript that once belonged to the duke of Bedford. This psalter too is decorated with a cycle of historiated initials depicting scenes of the psalmist's life, although in this instance the wedding of David and Michal illustrates Psalm 80 (Fig. 18). Once again the text makes no direct reference or allusion to marriage, but the verse beneath the initial, "Sound the trumpet on the memorable day of your solemnity" ("Buccinate . . . tuba in insigni die solemnitatis vestrae"), has been cleverly appropriated to warrant the use of subject matter that would otherwise seem irrelevant

Figure 19.

Marriage scene. Decretales of Gregory IX, English, second half of the thirteenth

century. Hereford, Cathedral Library, ms. O. VII. 7, fol. 156r.

Photo courtesy of the Hereford Mappa Mundi Trust and the Dean and Chapter

of Hereford.

to the psalm text, with the sounding trumpets effectively emphasizing both the solemnity and the public character of a legitimate wedding.

Relatively rare before about 1300, depictions of marriage ceremonies survive in large numbers from the fourteenth and especially from the fifteenth century, particularly in the form of manuscript miniatures illustrating a great variety of religious as well as secular texts. While representations of other aspects of the rite are occasionally encountered, the overwhelming majority of those with a transalpine provenance show the bride and groom standing side by side with their right hands either joined or about to be joined together by the priest, thus focusing on the central moment of the ceremony, the quintessence of what had come to be a sacramental rite.

The iconographic tradition is conveniently illustrated by several examples. A depiction of an aristocratic couple whose hands are joined by a bishop in an English miniature of the second half of the thirteenth century in the Hereford Cathedral Library Decretales (Fig. 19)

Figure 20.

The Marriage of Saint Waudru . Chroniques de Hainaut , vol. II, Bruges, 1468. Brussels, Bibliothèque

Royale Albert Ier , ms. 9243, fol. 103r.

is an unusually early instance of this iconographic type.[71] By the first decades of the fourteenth century, however, as exemplified by the French miniature in Figure 17, the type becomes common. The Marriage of Saint Waudru miniature from an important fifteenth-century Burgundian manuscript of the Chroniques de Hainaut (Fig. 20) vividly depicts a marriage ceremony in facie ecclesiae celebrated before a bishop within a church porch and in the presence of numerous guests, still segregated by gender as in the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaic (see Fig. 9). In the Sacrament of Marriage woodcut (Plate 5) from a Seven Sacraments cycle with Old Testament antetypes in the Paris 1492 L'Art de bien vivre,[72] the

scene of the priest joining the couple's hands in marriage replicates the vignette image above it that depicts the divine institution of marriage in the Garden of Eden, according to a common medieval exegesis of Genesis. The northern European iconography for representing marriage as a sacrament is thus constant in its essentials from the end of the thirteenth to the end of the fifteenth century, the only notable variants being the position of the bride, who may be depicted to the right or left of the groom, and the site of the ceremony, which in some places was moved from the entrance or porch of the church into the interior of the building, as is apparently the case in Plate 5.[73]

Within this larger context of continuity the specific details of marriage rites varied considerably from place to place during the later Middle Ages, but they were generally similar, if not precisely the same, within a given ecclesiastical region. Thus an ordo for matrimony in a rituale printed shortly after 1500 for use in the archdiocese of Reims, the metropolitan see of the ecclesiastical province in which Bruges and Ghent were then located, comes reasonably close in time and place to the Arnolfini double portrait. The rubrics of the Reims marriage service give an especially symbolic twist to the joining of the right hands, directing the priest to place the end of his stole over the joined hands of the bridal pair as they individually repeat the words of consent.[74] Although this ritual element is not found in the marriage ordo of a fourteenth-century missal once used in the cathedral of Tournai,[75] it does appear in a service book issued by the first bishop of Ghent in 1576, as well as in a Manuale pastorum published in 1591 for the diocese of Tournai. The Ghent and Tournai rites are virtually identical, and both are noteworthy for the introduction of a subtle but significant variation in the rubrics that accompany the joining of hands. Whereas in the Reims prototype the stole is merely placed over the hands, in the Ghent-Tournai rite the priest, having joined the hands, is directed to wrap the stole around the hands, binding them together in a symbolic way, as seen in Figure 20.[76]

It so happens that the Arnolfini double portrait is both preceded and followed by a famous Netherlandish painting in which this symbolic binding of the hands by the priest's stole is shown: Campin's Marriage of the Virgin (Plate 6) in the Prado, most likely painted a few years before the Arnolfini double portrait, and the marriage scene in Rogier's Seven Sacraments Altarpiece (Fig. 21) in Antwerp, completed shortly after the London painting. The currency of the stole-binding rite is thus documented with certainty in the diocese of Tournai during the 1430s, and since Rogier used the joined and bound hands to epitomize the sacramental aspect of marriage, its absence in a marriage picture by Jan van Eyck would be highly unusual and difficult to explain.[77]

Figure 21.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Sacrament of Marriage , detail of the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece,

c. 1448. Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten.

Photo copyright A.C.L. Brussels.

Figure 22.

Infrared detail photograph of Plate 1.

When the sacramental joining and binding of hands of the contemporary Flemish marriage ritual is compared with what is depicted in the London double portrait, it is evident that the hand gesture in the latter cannot represent the matrimonial joining of right hands for two reasons. In the first place, as has often been noted, it is not the man's right hand but his left that is in contact with the woman's right; all the attempts to explain the anomaly are unsatisfactory. Initially Panofsky himself suggested that the substitution of the man's left hand for the right was merely the result of artistic license, motivated by compositional considerations. Subsequently he cited the "not infrequent" linking of the left and right hands of husband and wife "often found" in English funerary monuments. But the docu-

mentation supporting these statements provides only conventional examples of the joining of right hands (as in Fig. 3).[78] In an addendum to Early Netherlandish Painting Panofsky returned to the problem, making reference to an Avignon marriage ritual in which the groom's left hand is indeed joined to the right hand of the bride. But rituals of this type are irrelevant to the Flemish context of the London picture, for they are peculiar to a few localities in the south of France, and the substitution of the groom's left for his right hand was evidently no more than a convenience, since the rubrics require the couple to turn and walk away from the priest with their hands still joined together.[79]

A further anomaly about the hand gesture that compromises the interpretation of the painting as a marriage picture has sometimes been noted in passing but without the obvious conclusion being drawn. Panofsky, for example, with a characteristically clever turn of phrase, remarked that the "husband gingerly holds the lady's right hand." Friedländer referred to the man "reaching out to her with his hand, against which she shyly and reluctantly lays her own," and Weale once wrote of the woman's hand that she "has laid hers in his left, stretched out towards her."[80] And in the 1523/24 inventory of Margaret of Austria's collection, which contains the earliest extant reference to the gesture, the central action of the double portrait is described as "ung homme et une femme estantz desboutz, touchantz la main l'ung de l'aultre," that is, "a man and a woman standing, the one touching the hand of the other."[81] To hold gingerly, or to touch, or to lay one's hand "shyly and reluctantly" on another's is not to join and bind, as the contemporary Flemish marriage rite demands, and thus what ought to be a joining of right hands, were this indeed the representation of a wedding ceremony, is not even a joining of hands. Finally, as revealed by infrared photography, a pentimento in the London double portrait indicates that the subtle nuances of the gesture were important to the painter (Fig. 22). Two fingers of the man's left hand, which initially extended slightly around and over the bottom side of the woman's hand, were deftly reworked as the picture was being painted, as if to strengthen and clarify the meaning of the gesture as a touching or receiving—as opposed to a joining and clasping—of hands.[82]