Heaven, Hell and Health

"That's the way it should be, they say. Such and such a percentage has to go every year, they say. . . . Where? To the devil, probably, so as to keep the rest fresh and uninterfered with."

Raskolnikov, in Crime and Punishment

In Russia and the rest of Europe, physicians and reformers engaged in heated debates regarding the eventual fates of women who worked as prostitutes. Opinion was divided over whether prostitutes simply rejoined the working class and urban poor, or whether they died young, casualties of disease and drunkenness. Was prostitution simply a stage that many young, female members of the lower classes passed through, as Parent-Duchâtelet asserted about Parisian women, or was it a final, fatal step for an unfortunate minority?[111]

The existence of regulation complicated the answer to this question, militating against a woman's simple change of trade. Regulation's opponents characterized the yellow ticket as an insurmountable obstacle for prostitutes who wanted to quit the profession. In his polemic against regulation, On the Binding of Woman to Prostitution (O prikreplenii zhenshchiny k prostitutsii) , the law professor Arkadii Elistratov blamed regulation for making it nearly impossible for a prostitute to change her ways.

[111] Writing of French prostitutes, Parent-Duchâtelet claimed that prostitution was but one phase in the life of many working-class women. According to his influential view, women workers simply drifted into prostitution and then passed out of it, eventually becoming ordinary members of the working class. See Harsin, Policing Prostitution, p. 103; Corbin, Women for Hire, p. 4. Parent-Duchâtelet's contention is called a "myth" in Frances Finnegan, Poverty and Prostitution: A Study of Victorian Prostitutes in York (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), p. 159.

Like a "stone" around a drowning woman's neck, regulation "paralyzes her last efforts" to rescue herself, "irrevocably dragging her to the bottom."[112] Elistratov and other critics stressed the permanence of the yellow ticket: once a woman registered, her status as a public woman was difficult to rescind.

A look at committee rules supports this interpretation; it was no simple matter to extricate oneself from the committee's watchful eye. According to ministry regulations issued in 1903, a woman might be stricken from police lists when it was ascertained that she had "quit the trade of vice." But many cities put hurdles in a woman's way by requiring more specific reasons for canceling registration, such as a "written declaration" in Astrakhan, proof of pregnancy or having reached one's fortieth birthday in Iaransk, and a marriage certificate in Ponevezh.[113] The St. Petersburg medical-police committee specified sickness, old age, death, confirmed possession of an "honest" job, relocation outside the committee's jurisdiction, or entry into the House of Mercy or an ROZZh rehabilitation program. Registration could also be revoked at the request of a verifiably reliable person or if a woman's parents, relatives, or guardians demanded that she be removed from the inscription lists.[114] The rules of 1903 prohibited confiscation of an odinochka's passport, yet the police might still write on it the telling words, "lives by her own means" (zhivet svoimi sredstvami ). As prostitutes interned in Kalinkin Hospital complained to Aleksandra Dement'eva of the OPMD, everyone knew quite well that this indicated a woman supported herself through prostitution.[115] Former prostitutes, as well as their concierges and doormen, could expect surprise visits from medical-police agents intent on verifying a woman's new status. Even after a woman had been taken off medical-police records, she was obligated to appear after a certain amount of time for a follow-up medical examination. Should the examining physician discover signs of what he judged to be promiscuous sexual activity, the woman would be registered once again. All of these practices slowed a woman's ability to put the trade of prostitution behind her.

Observers also cited soaring rates of venereal disease and alcoholism to reinforce arguments about prostitution's deadly cost. Venereal dis-

[112] Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, p. 1

[113] These examples are from Di-Sen'i, "O sovremennoi postanovke," p. 466.

[114] Di-Sen'i and Fon-Vitte, Vrachebno-politseiskii nadzor, p. 26; Elistratov, O prikreplenii zhenshchiny, pp. 49–55.

[115] Dement'eva, "Otritsatel'nyia storony," p. 509.

ease represented more than an occupational hazard for prostitutes; contraction was almost inevitable. To be sure, turn-of-the-century physicians often mistook simple vaginal ailments for gonorrhea and syphilis, and they rarely adhered to any standard norms in formulating statistics. But even if they diagnosed only three-fourths of the women in their studies correctly, they were still discovering epidemic rates of syphilis and gonorrhea. In 1889, A. Dubrovskii, the editor of an empirewide census of Russian prostitution, estimated that 58 percent of all registered prostitutes suffered from a venereal disease. In Oboznenko's sample, around half the prostitutes contracted syphilis or gonorrhea during the very first year after registration. One well-known venereal specialist, Aleksandr Vvedenskii, estimated that 93 percent of all prostitutes would contract syphilis during the first three years of their career.[116]

The links between syphilis and long-term chronic illnesses were confirmed by the work of scientists like Alfred Fournier and Jonathan Hutchinson at the end of the nineteenth century. The risks of future complications like paralysis, insanity, blindness, and other serious ailments could, however, take on a more definite quality in contemporary works. Syphilis assumed a particularly nightmarish quality in popular fiction. To the 17-year-old youth who contracted syphilis from a prostitute in Leonid Andreev's "In the Fog" ("V tumane"), his disease was "more horrible than deadly, murderous wars, more devastating than the plague and cholera." In despair, he stabbed a prostitute to death and then turned the knife on himself.[117] In Iama, Kuprin publicized what he took to be syphilis's terrible dangers through the prostitute Zhenia. When a military cadet told her he knew about syphilis—"That's when your nose falls off"—she passionately retorted,

No, Kolia, not only your nose! Everything gets sick: a person's bones, veins, brain. . . . Doctors say otherwise—that it's a trifle, that it's possible to be cured. That's baloney! You can never be cured! A person rots for ten, twenty, thirty years. At any moment, he can be crushed by paralysis and the right half of his face, his right arm, his right leg will die, and he won't be a person anymore, but some kind of half-person—half-man, half-corpse. The majority lose their minds. And everyone understands, every person with this disease understands, that if he eats, drinks, kisses, even breathes, he

[116] Dubrovskii, Statistika Rossiiskoi Imperii, p. xxvi; Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, pp. 51, 56; Shtiurmer cites Vvedenskii in "Prostitutsiia v gorodakh," p. 69. Of the 496 women who registered in St. Petersburg in 1890, 74 were diagnosed as having contracted syphilis by the year's end. Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, p. 53.

[117] Leonid Andreev, "V tumane," Polnoe sobranie sochinenii, vol. 7, bk. 14 (St. Petersburg, 1913), pp. 130–57.

can't be sure he's not going to infect someone around him, someone from his closest family—his sister, his wife, his son. . . . The children born to syphilitics are all monsters, prematurely born, sick with goiters, consumption, idiots.[118]

Zhenia (and, by extension, Kuprin) misrepresented syphilis as an airborne contagion that irrevocably canned its victims and everyone they touched.

Fiction writers were not the only ones guilty of hyperbole in this area. Physicians also lacked clear notions about the epidemiology of venereal diseases, often confusing moral issues with medical ones.[119] As late as 1897, a Kalinkin Hospital commission inaccurately described non-syphilitic venereal infections (including gonorrhea) as able to "pass after several weeks without leaving a trace." Syphilis, however, was considered infectious enough to be passed along on kitchen utensils.[120] A 1904 book entitled The Great Evil (Velikoe zlo) by a Moscow University professor, Mikhail Chlenov, provides us with an excellent example of how prevention often blurred the lines between science and morality. Chlenov advised men with gonorrhea to sleep on cold, hard beds, to refrain from eating rich foods and, to avoid not only sexual relations, but the sexual excitement induced by pornographic books and pictures, and female company. Horses posed a threat to health; trains did not. Underwear and clothing could also serve as transmitters for gonococci. Syphilis represented an even greater danger, as it lived in clothing, cigarettes, pipes, toys, musical instruments, utensils—essentially, most items that were passed from hand to hand or mouth to mouth. Chlenov even knew of one clerk with a syphilitic sore on her tongue. Rather than tracing her lesion to sexual contact, physicians attributed it to her habit of licking her finger when she counted money. Condoms served no purpose in prevention as they could easily break and, by Chlenov's reckoning, harmed the nervous system.[121]

Prostitution was portrayed as endangering women's health in other ways as well. One study by a female physician for the Moscow Venerological and Dermatological Society showed that irregular periods and

[118] Kuprin, Iama, p. 249.

[119] In "Morality and the Wooden Spoon," Laura Engelstein argues that Russian physicians were reluctant to attribute the spread of venereal disease among the common people to sexual means.

[120] "O prizrenii sifiliticheskikh, venericheskikh, i kozhnykh bol'nykh," pp. 296–97. Aleksandrovsk medical-police rules prohibited prostitutes with sores on their lips from sharing cups, utensils, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes. Di-Sen'i, "O sovremennoi postanovke," p. 468.

[121] Chlenov, Velikoe zlo (St. Petersburg, 1904), pp. 7, 29, 31–32, 62–64, 111.

spontaneous abortions occurred with particular frequency among prostitutes.[122] Prostitutes also suffered from sexually transmitted diseases other than syphilis and gonorrhea, as well as vaginal and pelvic infections, and traumas to the sexual organs.[123] Most accounts of brothel life attested to an endless stream of customers, and punishments enforced by madams and their assistants.

Judging by the anecdotal evidence, alcoholism was also one of prostitution's more obvious bedfellows, its "inevitable companion."[124] Not only was the sale of alcohol at inflated prices used to fill the coffers of brothelkeepers, it was also a common prelude to relations between odinochki and their clients. A temperance crusader described how guests would arrive at brothels from restaurants cafes, and bars "sufficiently loaded" and then, despite the rules prohibiting its sale, find more liquor readily available. Expensive brothels sold various sorts of champagne; in the lower-priced houses, madams would sell lemonade, kvass, and "whatever" (chto takoe ), all spiked with cheap vodka. Guests wary of the brothels' high markup on liquor prices and the way madams would pass off drinks of the poorest quality might also sneak in their own supply past the bouncer stationed at the door. "Athenian nights," drinking bouts "en grand, " would be held at the fancier establishments.[125]

Many observers approached this issue in a way that reflected their inability to comprehend how women could otherwise bring themselves to engage in commercial sex. They readily believed that drinking played an important role in quelling "natural female modesty." Dement'eva, for example, told of a young prostitute she chided for drinking who snapped in response, "Yeah, would you really approach this life sober?"[126] Although observers repeatedly remarked on the heavy drinking

[122] Dr. Vera I. Arkhangel'skaia found that 16 percent of her subjects had irregular periods, only 12 percent had experienced pregnancy, and that miscarriages were three times more prevalent among prostitutes than among the rest of the female population. Unfortunately, we cannot determine whether these figures reflected self-induced abortions, the widespread use of contraceptives, or infertility. Vrach, no. 13 (1898): 394.

[123] See Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood, p. 99.

[124] Dmitrii Borodin, "Alkogolizm i prostitutsiia," Trezvost' i berezhlivost', no. 2 (February 1903): 13; no. 3 (March 1903): 2. See also Dement'eva, "Otritsatel'nyia storony," p. 506. Ermolai Erazm, a mid-sixteenth-century churchman, wrote, "if there be no drunkenness in our land, there will be no whoring for married women. . . ." Quoted in R. E. F. Smith and David Christian, Bread and Salt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), p. 92.

[125] Borodin, "Alkogolizm i prostitutsiia," Trezvost' i berezhlivost', no. 2 (February 1903): 11, 13; no. 3 (March 1903): 2.

[126] Dement'eva, "Otritsatel'nyia storony," p. 506.

in brothels and the pervasive drunkenness among prostitutes, regrettably, few conducted serious research on the consumption of alcohol. Two minor studies, one conducted in Baku and the other in Odessa, showed respectively that 61 and 75 percent of the prostitutes surveyed in these cities admitted to using alcohol. In Odessa, a full 48 percent of the women told the researcher that they got drunk every night.[127]

Most of the literature in Russia portrayed prostitutes as meeting a sad end in the back alleys of a big city. Fedorov's numbers on prostitutes who died in 1889, 1890, and 1895 provide little statistical confirmation for this vision, however. Among 972 women who were removed from the registration lists of the St. Petersburg medical-police committee in 1889, 55 (6 percent) had died, 32 (6 percent) of 581 died in 1890, and 47 (8 percent) of 621 died in 1895.[128]

Since observers never succeeded in charting the life cycles of most women who earned money as prostitutes, descriptions primarily functioned as cautionary morality. As A. I. Matiushenskii, author of The Sex Market and Sexual Relations(Polovoi rynok i polovjia otnosheniia ) put it, "It follows that as a general rule, it is possible to assume that the prostitute always dies a prostitute." One book described how destitute prostitutes, those too old or dissipated to succeed at their trade, lived in St. Petersburg's Haymarket. According to this source, these women "almost never wash, and wear clothes until they fall to pieces from rot. Their apartments are so disgusting that it is impossible to imagine anything more vile." Bentovin also believed that the decline was inevitable. He discerned three stages in a prostitute's career. She would begin in her teens, too inexperienced to get rich at her trade. However, at the age of 20 a smart and lucky prostitute might have enough experience to earn a lot of money. By the age of 30, years of alcohol abuse and disease would have taken their toll, and prostitutes would be left to collect 25 or 30 kopecks for quick trysts. Fedorov commented that most prostitutes ended their days tragically—in hospitals and cheap flophouses.[129]

[127] Though these numbers are not reliable, they probably suffer from underreporting rather than overrepresentation, given some women's reluctance to admit their drunkenness. Melik-Pashaev, "Prostitutsiia v gorode Baku," p. 857; "Prostitutsiia v Odesse," Odesskie noposti, no. 5216 (February 18, 1901): 3.

[128] Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, p. 46; Fedorov, "Deiatel'nost' S.-Peterburgskago vrachebno-politseiskago komiteta," p. 185.

[129] A. I. Matiushenskii, Polovoi rynok i polovjia otnosheniia (St. Petersburg, 1908), p. 97; Prostitutsiia v Rossii, p. 160; Bentovin, "Torguiushchiia telom," pp. 171–72; Fedorov, Ocherk vrachebno-politseiskago nadzora, p. 22.

With similar goals in mind, observers maintained that high rates of suicide and attempted suicide were common to the trade.[130] Dr. M. A. Kalmykov claimed that nearly half the suicides in his city, Rostov-on-the-Don, were committed by prostitutes. To him, suicide represented a form of moral justice. "This is evidence," he wrote, "that even such a lowly trade does not extinguish the spark of God in the prostitutes and that the consciousness of the horror of their fall and the infamy of their position brings them to the decision to finish off their ruined lives."[131] Another doctor noted to the 1897 congress on syphilis that scarcely a night at the Kazan city hospital passed without an incident involving the self-poisoning of a brothel prostitute. These incidents were so frequent, he said, that the hospital installed a stomach pump in the reception room. Dr. Zinaida El'tsina confirmed that an "entire mass" of prostitutes poisoned themselves in Nizhnii Novgorod each summer. This showed "how burdensome their profession is for prostitutes."[132] An 1885 newspaper article printed the final words of a Kharkov prostitute who poisoned herself with phosphorous and then refused treatment. According to the article, she kept repeating, "Release me from this hell. I have no more strength to suffer."[133]

At the 1910 Congress for the Struggle against the Trade in Women, one doctor asserted that 13 percent of prostitutes in St. Petersburg ended their lives in suicide. This rate was several times higher than that of the capital's population in general. He attributed this phenomenon both to the abnormal conditions of prostitution and the overall circumstances of urban life. Half these prostitutes attempted suicide between the ages of 16 and 20, usually with poison. In the majority of cases, prostitutes killed themselves while drunk. Interestingly, the incidence of double or triple suicide was higher for prostitutes than for the rest of the population, suggesting perhaps a camaraderie of sorrow and misery.[134]

[130] Rosen's sources suggested high rates of depression and suicide for American prostitutes as well. Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood, pp. 99–100.

[131] M. A. Kalmykov, "K voprosu o reglamentatsii prostitutsii i abolitsionizme,' O reglamentatsii prostitutsii i abolitsionizme, p. 73.

[132] "Protokoly obshchikh zasedanii," p. 132.

[133] Russkie vedomosti (June 19, 1885), quoted in Muratov, "Vrachebno-politseiskii nadzor," p. 407.

[134] Nikolai I. Grigor'ev, "Samoubiistva prostitutok v gorode S.-Peterburge (1906–1909 gg.)," Trudy s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 2, p. 558. Accordingly, even Kuprin's Zhenia, the most outspoken prostitute in Iama, ended her own life when she learned she had contracted syphilis. So did the author of the purported diary, Belaia rabynia, p. 16.

To be sure, many prostitutes felt burdened by their trade. Disease and drunkenness would most certainly have complicated attempts of former prostitutes to marry, raise children, and integrate themselves into "respectable" working-class communities. On the other hand, as we saw, moral and political imperatives clouded the judgment of many contemporary observers. Kalmykov and El'tsina presumed much about the causes of the suicides they witnessed. Though they provided no evidence, they nonetheless asserted that the dead women were running from prostitution itself.

Doomsday projections about syphilis and its long-term consequences also adhered to their own agenda. Some observers wished to impress on Russian society the dangers of diseases once considered transitory and relatively harmless. Others hoped to bolster their support for regulation by asserting that venereal diseases were so serious that they required strict government vigilance. Physicians and other experts often failed to stress that in its tertiary stage, syphilis remained dormant for many years and that most sufferers did not face its more extreme consequences. Though syphilis, with all its attendant pain and risks, was a serious illness that afflicted many prostitutes, it did not pave a straight path to death's door. Moreover, as we have seen, the cure could be more traumatic than the disease.

Though the yellow ticket distinguished registered prostitutes from other women, most succeeded in discarding it one way or another. A significant percentage of registered prostitutes stopped fulfilling their obligations and disappeared from medical-police scrutiny. While this cannot be verified statistically, it is likely that most found other jobs and established families. The police succeeded in maintaining records only for those women who remained on the registration lists. As we have seen, most women who earned money at prostitution did so casually or clandestinely, and thus stayed outside the policeman's (and statistician's) reach. Furthermore, most ventures into commercial sex were sporadic, based on the particular circumstances of a woman at a particular time of her life.

On the average, women who registered seem to have stayed in the life for around five years. Six hundred prostitutes studied by the House of Mercy in 1910 had worked an average of five years and three months as prostitutes. Oboznenko's research also indicated a five-year stint in registered prostitution, but he believed that this number was somewhat inflated. According to his findings, there were two types of prostitutes in St. Petersburg: habitual prostitutes who remained in the trade much

longer than the five-year term, and women who worked as prostitutes only temporarily. The latter group generally quit within three years."[135]

Our best sketch of aging prostitutes comes from Oboznenko, who, in an attempt to discover some prostitutes' natural immunities, described in detail twenty women who had been registered in the trade for more than ten years, all or most of them in brothels, and had never contracted syphilis.[136] These portraits are remarkable for their bleak depiction of poverty, hardship, and illness, three circumstances that were inextricably linked to these women's personal histories.

Of the twenty prostitutes, eleven were drinkers or alcoholics, and another five drank "in moderation." Thirteen reported that their fathers were alcoholics, and four had alcoholic mothers and fathers. Nine had parents who suffered from tuberculosis. One 40-year-old woman, a peasant and former day laborer with the initials "A. R.," came from a family of sixteen children, of which only four survived past the age of 10. Between 1884 and 1896, A. R. had been interned in Kalinkin for various nonsyphilitic ailments thirty-four times. Her mother and father lived to old age (65 and 80 respectively), despite the fact that her father was a drunkard. An alcoholic woman with epilepsy was described as covered with scars she had suffered during her periodic fits. "E. K.," nearly deaf in one ear from a recent beating, became a prostitute at age 12 after she lost her virginity while drunk. Her sister also worked as a prostitute in St. Petersburg. Another woman turned to prostitution because she had an "aversion for work, and a passion for drink and the dissolute life." At 34, she had been a prostitute for seventeen years. "E. S.," who was 37 years old, had been registered as a prostitute for twenty-one years, but had been working the streets since she was 12. She characterized both her parents as drunkards, and spoke of a mother with rheumatism who had been bedridden for two years. An alcoholic peasant referred to as "M. T." had lived in brothels for fourteen years, and had been dispatched to Kalinkin Hospital eighteen times. One "A. P.," who was raised in a foundling home, said her mother became a prostitute when A. P. was 10 years old. A woman from Tambov province came from a family of sixteen brothers and sisters, only three of whom were still living. "A. S.," a 30-year-old peasant from a Baltic province, lost both her parents when she was 3 years old.

[135] Raisa L. Depp, "O dannykh ankety, proizvedennoi sredi prostitutok S.-Peterburga," Trudy s"ezda po bor'be s torgom zhenshchinami, vol. 1, p. 146; Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, p. 14.

[136] Oboznenko, Podnadzornaia prostitutsiia, pp. 61–90.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These stories depict terrible family tragedies and endemic diseases in this particular group. Most important, though, is the fact that Oboznenko's aging prostitutes were atypical; their exceptional status helps prove the more likely rule about prostitution as a risky trade, but one that could nevertheless be left behind.

If we look closely at some figures provided by the medical-police committee in St. Petersburg, we can see that officialdom could not really account for most former prostitutes. Fedorov, for example, provided lists of 2,174 women who went off the St. Petersburg committee lists in 1889, 1890, and 1895 (see table 1). Though it was assumed that the women who "concealed themselves" from nadzor were continuing to earn money through prostitution, this was not necessarily the case. A yellow ticket would have frustrated efforts to find housing and regular employment, but a woman could have bribed her way into a desired situation, purchased a forged passport, or returned home to her village without one.[137] Unfortunately, categories like "abandoned debauchery" and "voluntarily departed" do not tell us much about the fates of these women or the reasons why the committee removed them from the rolls. Yet it is still obvious that substantial numbers of women in St. Petersburg either quit registered prostitution or at least learned to elude com-

[137] Barbara Engel believes that these scenarios were common. Engel, "St. Petersburg Prostitutes," p. 42.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

mittee agents. Though not in the majority, significant numbers of women did enter stable relationships (i.e., submitted proof of patronage or got married). If we take into consideration that many of the women who vanished from the sight of committee officials blended into urban and village communities, then we can assume that, in reality, most prostitutes did eventually give up their trade.

A report from the St. Petersburg medical-police committee to the UGVI for the year 1909 listed 341 prostitutes as having been removed from the records. Their reasons are summarized in table 2. These numbers suggest that most women reintegrated themselves back into "respectable" village and urban communities. Those who left, however, did so with little to show for their labors. Savings from the "wages of sin" were rare. More likely, former prostitutes had acquired some kind of venereal disease, an alcohol dependency, and perhaps habits from the brothel or the street that would keep them feeling separate from other women. Still, the permeability of the trade of prostitution marked a woman's venture into commercial sex more as a temporary strategy for survival in an economically cruel world than as her life or her everlasting fate.

The regulatory system had been implemented to curb the spread of venereal diseases and exercise control over a disorderly section of the population. Toward these ends, policemen and doctors monitored women of the urban lower classes and drew thousands into

the world of identification, inspection, and incarceration. But as the president of the OPMD pointed out, the very existence of regulation created a whole new problem for the tsarist authorities: clandestine prostitution was in fact "a logical consequence of nadzor itself."[138] By attempting to put all prostitutes under control, the state created a class of women who would do their best to avoid detection and scrutiny. "Clandestine prostitution" inevitably accompanied regulation, always working to thwart, undermine, and counter the regulatory system's efforts. Regulation failed to bring order to the disorderly. Instead, it engendered different forms of disorder. Not only did it beget clandestine prostitutes, it constructed institutional settings for abuses of power, arbitrary authority, corruption, scandals, fighting, riots, and other mayhem.

Regulation also subverted its own medical goals. The state's attitude toward children identified as prostitutes demonstrated this very well. Though the authorities feared unchecked venereal disease, they halted before taking regulationist ideology to its logical end by wedding minors to the yellow ticket. As for adults, women who feared the police often hid their venereal symptoms and as a result not only suffered the physical consequences themselves, but could serve as further transmitters. Even as the doctors and policemen locked up hundreds of prostitutes in hospital wards, thousands more women with contagious venereal diseases were still at large and determined to remain so. Manuil Margulies, in a 1903 book entitled Regulation and "Free" Prostitution (Reglamentatsiia i "svobodnaia" prostitutsiia ), maintained that the regulatory system manufactured its own criminals. The more rigid the system, the more women would attempt to circumvent it, particularly if they suffered from an illness and therefore had something to fear from discovery.[139] Moreover, the medical procedures themselves may have served to spread infection at the same time they supposedly limited it. In effect, the medical side of regulation probably did more damage than good from an epidemiological and social standpoint. Here too, then, we can judge regulation a failure.

Registered or not, all women who engaged in prostitution had to contend with the institution of nadzor. Nadzor shaped what lay in store

[138] "Soobshchenie obshchestva popecheniia o molodykh devitsakh v S.-Peterburge," Izvestiia S.Peterburgskago gorodskoi dumy, no. 21 (May 1914): 2054. In Policing Prostitution, pp. 241–42, Harsin also points out that by developing a regulatory system the police created clandestine prostitution.

[139] Manuil S. Margulies, Reglamentatsiia i "svobodnaia" prostitutsiia (St. Petersburg, 1903), p. 8.

for them on the streets and defined where they stood in relation to the police and their community. If they held the yellow ticket, they could pursue their trade, but they were supposed to conform to medical-police restrictions and examination schedules, as well as submit to hospitalization at their doctor's orders. If they engaged in clandestine prostitution, they had more options, but they ran the risk of arrest and legal prosecution for disobeying ministry regulations. If they were discovered to have venereal disease, hospitalization awaited them in either case. The choice was not an easy one; the dangers were great whichever way a woman went and the rewards were questionable. Yet tens of thousands of women registered as prostitutes and even greater numbers engaged in prostitution without official permission. The "laws of the market" were key here, for the "supply" of prostitutes existed in relation to a significant male "demand."

Figure 1.

Norblin de la Gourdaine, sketch of A. O. Orlovskii with a tavern-keeper on his lap

(late eighteenth century). From V. A. Vereshchagin, Russkaia karikatura , vol. 3

(St. Petersburg, 1915). Chesler Collection, Florham-Madison Campus Library,

Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Figure 2.

Drunken prostitute outside a tavern. From Erich Müller, Sitten-Geschichte Russlands:

Entwicklung der sozialen kultur russlands im 20. jahrhundert (Stuttgart, 1931). Chesler

Collection, Florham-Madison Campus Library, Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Figure 3.

"Troika" — a drunken gentleman with a prostitute on each arm. From Müller, Sitten-Geschichte

Russlands . Chesler Collection, Florham-Madison Campus Library, Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Figure 4.

Prostitute and sailor. She: "Yeah, you can take a lot from a soldier!"

He: "Only a fool would say that's going to happen. Do you honestly think

a soldier would even talk to you?" From Aleksandr I. Lebedev, Pogibshiia,

no milyia sozdan'ia , tetrad 1 (St. Petersburg, 1862–63). Slavic and Baltic

Reserve, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Figure 5.

Brothel prostitute and client. He: "Tell me, please, how'd you wind up here?"

She: "Real easy. My lover went to Novgorod for a while. I got bored. . . .

And now I'm in debt." From Lebedev, Pogibshiia, no milyia sozdan'ia . Slavic

and Baltic Reserve, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Figure 6.

Two prostitutes sitting at a table. First one: "Iashlev offered me 100 rubles, Rylkin

200, Shumov 250. So what do you think, Marie?" Second one: "What's to decide

here? Take from everyone—then you won't insult anybody." From Lebedev,

Pogibshiia, no milyia sozdan'ia . Slavic and Baltic Reserve, The New York Public Library,

Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

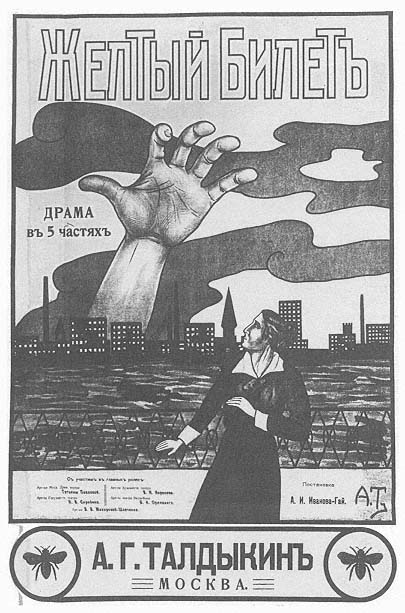

Figure 7.

Advertisement for "The Yellow Ticket: A Drama in Five Parts." My

thanks to Louise McReynolds for supplying me with this photograph.