Chapter Six—

Of the Livestock in California

Animal husbandry was the other temporal matter which required much care and thought at the California missions, and without which they could not have survived. For that reason, horses and donkeys, cows and oxen, goats and sheep were brought there in the very beginning. Had any of these animals known about California or how badly they and their offspring would fare in the new colony, they would surely have preferred a hundred times to run away as far as their legs could carry them rather than to let themselves be shipped to California.

Cattle, sheep, and goats had to supply the meat for the healthy and the sick, but they were also needed because their tallow was used to make candles and soap, for ships and boats, and they furnished the fat to prepare the beans. In California as well as elsewhere in America, the beans are not prepared with butter churned from milk, but with the so-called lard or rendered fat and the marrow of the bones. For this purpose, every time a well-fed cow or ox was killed, which was a rare occurrence, every bit of fat was carefully cut from the meat, rendered, and conserved in skin bags and bladders. This fat was used for the preparation of food and for frying the very lean or dried meat. Some of the hides were tanned for shoes and saddles and for bags in which everything was carried from the field to the mission or anywhere else. Other skins were used raw to make sandals for the natives, or were cut into strips for ropes, cords, or thongs, which were used for tying, packing, and other similar tasks. The natives used the horns to scoop up water or to fetch food from the mission.

Without horses or mules it would also have been impossible to exist. They were needed for guarding the cattle and carrying burdens, and also as a means for traveling by the missionary or by the soldier. It would have been difficult to make much progress on foot in such a hot and uneven land.

Sheep too can serve a good purpose for people who have no clothes—if only the flocks had not been so small because of the lack of feed. Moreover, the sheep left a good part of their fleece on the thorns through which they passed. Wherever a flock could be maintained and increased to a good number, there were also spinning wheels and weaving looms, and the people received new outfits more frequently than at other missions. Of pigs, there were hardly a dozen in the whole land, perhaps because they cannot root up the dry, hard ground and have no mud holes to wallow in.

Wherever circumstances permitted it, no labor was spared to plant or seed the ground. Small or large herds of sheep and goats were maintained, as well as a "flying corps" of cows and oxen, and care was taken that horses and mules would not die out.

The goats and sheep returned every evening with full or empty stomachs to their folds. At times it was difficult to extract a pint of milk from six of the goats. The cattle had free passage and were per-

mitted to wander fifteen and more hours in every direction to find their feed. They were brought in only once a year when their tails were trimmed to make halters from the hair. At the same time, the calves born during the last year had a piece clipped off their ears and were branded with a sign, so that they could be identified if they lost their way or strayed into other territory. The same thing was done to colts and young mules.

To keep the livestock from straying too far, or from disappearing entirely, five or six herders were necessary. It was their job to ride one week in one direction, the next week in another, in order to keep the animals closer together. When the herders rode forth, they always took half a legion of horses or mules with them. Then they would go at full gallop over mountains and valleys, over rocks and thorns. Since neither horse nor mule was shod and fodder was so scarce and poor, and since at times the galloping lasted for many days, often weeks in succession, the herders needed to change their mounts many times a day. To protect a few hundred cows, therefore, almost as may horses were required. Hunger alone did not make these animals run so far afield. They also suffered from persecution by the natives, who killed more of them in the open than were brought to the mission for slaughter; nor did the Indians spare horses or mules. They relished the meat of the one as much as that of the other.

All these animals were very small. Scarcely three or four hundred pounds of meat and bones could be obtained from a steer. The milk was only for the calves. I have already reported in another chapter that for nine months of the year the animals were as skinny as dogs and carried not a pound of fat on their bodies. They ate thorns, two inches long, together with stems, as though they were the tastiest of grasses. Thus, except to furnish poor and insufficient food for not too many people, three or four hundred head of such cattle barely paid enough to buy the bread that two Spanish cow herders and their helpers ate in one year. Yet the herders were as essential at some missions as was the livestock. To allow the animals to go unguarded in California was like sending them to the slaughtering bench, or like setting the wolf to guard the sheep.

The goats and sheep were no better off than the cattle, and the laziness of the native herders added a good deal to their hardships.

More than once during these seventeen years have I seen a flock of sheep numbering four to five hundred head reduced by hunger to eighty or even fifty. More than half of this time I received very little from them, because after they were skinned, the carcasses were more fit to be used as lanterns at nighttime than as roasts in the kitchen.

Among the California horses there was one very good strain, agile and hardy. They were small, however, and increased in number very slowly, so that every year others had to be bought outside of California to keep the soldiers mounted. Only the donkey, who is not so fussy and always patient wherever it may be, was fairly well off in California. It worked little and ate the thorns and stalks as though eating the finest oats.

If what I have reported in this and in the preceding chapter about agriculture and animal husbandry in California should lead to the conclusion, or even suggest, that the missionaries sought or found profit in these activities, such would be an error. I knew not one among them who did not regard this work as a heavy burden which he would gladly have slipped from his shoulders. It was definitely a hardship—equal to the services of shiftless soldiers—which had to be endured in order to help the California Indians win the Kingdom of Heaven. Aside from this benefit, the natives derived another profit from the labors of the missionaries. Through small gifts the hearts of a poor, barbarian people could be won, and such gifts saved many of them from pernicious laziness and idle roving.

Furthermore, even if the mountains of California had been made of solid silver, I cannot see what temporal prestige or selfish gain the missionaries could have acquired from such labor and worry, to which they certainly were not accustomed. Voluntarily and irrevocably they left their country, parents, brothers and sisters, friends and acquaintances, and last but not least, an easy life, free from worries, to enter an existence full of a thousand dangers on water and on land. All this they endured so they could, in the New World, in a wilderness, among wild and inhuman people, among disgusting vermin and cruel beasts, live well and gather wealth for others! To judge, to speak, or to write in such a way is not just average stupidity. It is rather to brand as the world's biggest fools a number of intelligent men, of whom it is said and written that they are not lacking in knowledge and reason. In respect to "gathering wealth for others," Father Daniel has already said, a short time ago, that since

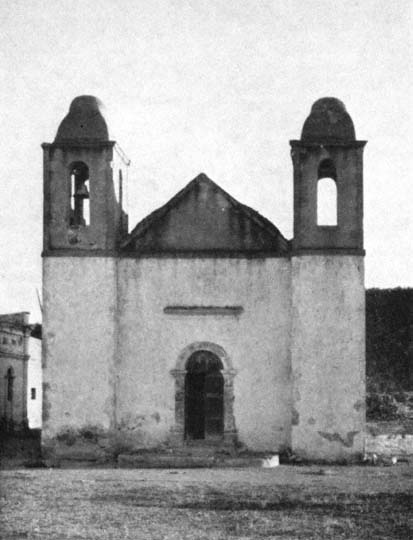

Father Baegert's Mission San Luis Gonzaga

Automobile Club of Southern Calafornia

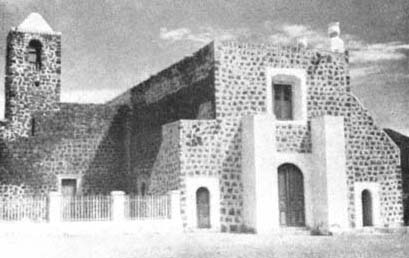

Nuestro Padre San Ignacio de Kadakaamang

Neal R. Harlow

Santa Rosalía de Mulegé

Neal R. Harlow

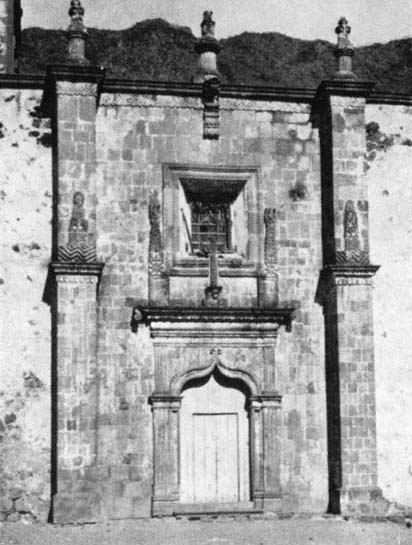

San Francisco Xavier de Biaundo

Neal R. Harlow

Side Door of Mission San Francisco Xavier

Neal R. Harlow

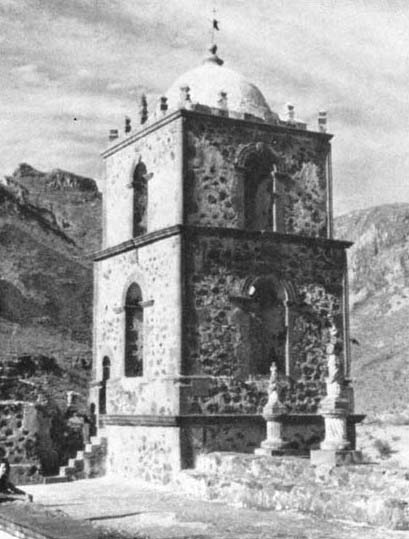

Tower of Mission San Francisco Xavier

Neal R. Harlow

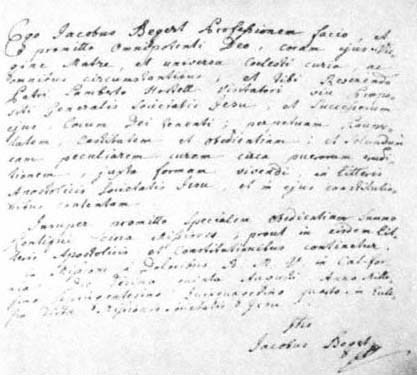

Father Baegert's Profession, August 15, 1754

Archives of the Society of Jesus, Rome

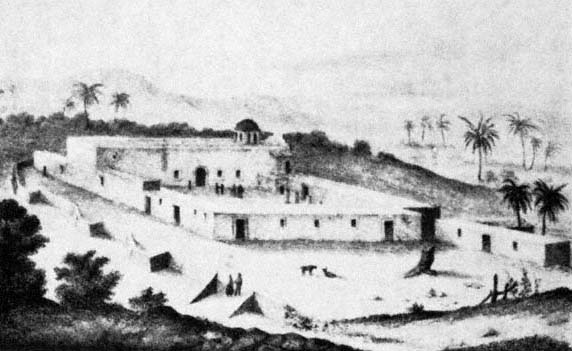

Nuestra Señora de Loreto, Mother Mission of the Californias

Rivera Cambas, Mexico Pintoresco

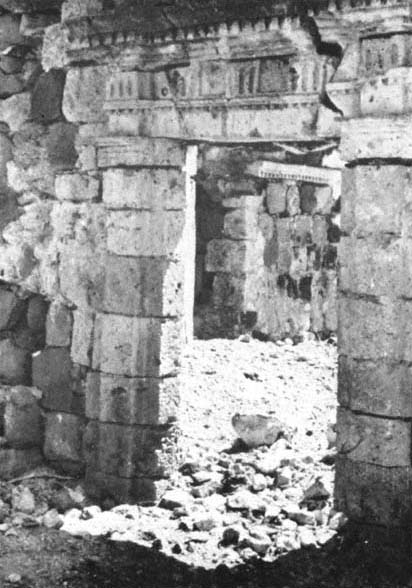

Ruins of the Chapel of Mission San Juan Londó

Neal R. Harlow

the beginning of the world, no one has ever heard of a band of thieves or robbers in which any of the group chose to live alone in the forests in constant danger of being broken on the wheel, so that the rest of the band might live in the city, well and at ease, and become wealthy from loot.

To tell the truth, for eight years I also had four to five hundred head of cattle and as many sheep and goats running around in California, until the thieving of the Indians from my own and another mission forced me to do away with them. For several years I had a small field of sugar cane in front of my house, until the Indians again went too far and pulled up nearly all of it before it was ripe. In six or seven years I gathered several thousand bushels of grain—corn and wheat—from the six or seven small pieces of land which I had caused to be planted here and there. Yet most of the time I had no bread in my house. And when I wished to honor a guest, I had to request a fowl from one of my soldiers—who kept a few chickens on his own corn rations—while I saved my wheat and corn for needy Indians. In my kitchen I also used suet, even on days of fasting, because I had no butter. In many years I hardly tasted meat other than that of lean bulls, which were killed every fourteen days. I never had veal. I seldom saw my roasting spit on the table, although more than once I saw maggots there. Finally, not to mention many other things, I often found myself forced to give up the evening meal entirely because I had nothing I cared to eat. For several years I fasted for forty days on dry vegetables and salted fish five or six times within twelve months. To let the fish swim in their element, my drink was precious, although not always the freshest, water.

Several times I could have changed my post and gone to another place where, I am sure, I would have found better food and many other things I did not have, but it was not very hard for me to resist the temptation. In California the missionary has small regard for temporal goods or personal advantages.

Now is the time to answer the third question in Part Three, chapter four, as I have promised to do. How then was it possible, in a poor land like California, to acquire such beautiful and rich church ornaments? Answer: It was possible to acquire them: first, from the thousand florins or more per year which represented the income from the endowed estates to each mission; second, from the sale of wheat and corn, wine and

brandy (the latter was distilled from wine which was about to turn to vinegar), sugar, dried figs and grapes, cotton, meat, candles, soap, fat, leather, horses, and mules, all being products grown or made at the missions. These exceeded what the missionary needed for the support of the mission, and were sold to the soldiers, sailors, and miners. These sales could hardly have been refused, especially in cases of necessity, when crops had failed outside of California. Furthermore, whatever was of no value to the Indians was sold. Finally, everything a missionary could have but did not use for his own person, that is to say, what he denied himself, was also sold. Soldiers and other people often drank wine which the missionary could have enjoyed himself without drinking to excess. A good deal of this income was used to supply the Indians with clothes and provisions which they lacked and which had to be purchased. With the remainder the above-mentioned costly church ornaments were acquired little by little.

If anyone wishes to find fault with such expenditures or wishes to raise his voice against them—like the traitor Judas against the extravagance of Magdalene (John XII)—as someone has done in the Spanish language, although not about the California missions but about the churches of a certain religious order in general, and if he be a Christian, a Catholic Christian, I refer him to the words in Psalm XXV: "Domine, dilexi decorem domus tuæ." (Lord, I have striven for the beauty and adornment of thy house.) I wish also to advise him to look homeward concerning extravagance, and to criticize the silver dishes, tapestries, and the like found nowadays in private homes before he censures the ornaments in the houses of the Lord.

Leave to the Lutherans and Calvinists—until God will convert them—their austere altars, their bare walls and empty barns, and let us beautify our churches as true houses of God, as best we can. Those who do not care to contribute should leave other people who desire to do so unmolested.

It was impossible to use all the revenue from animal breeding or agriculture for the benefit of the Indians. They were poor, so poor that their poverty could not be greater, but their poverty is of a different nature and character from that prevalent among so many people in Europe. An Indian cannot be helped by paying his debts or by releasing him from prison, by giving money to a girl so that she might enter a con-

vent or be married. It is not necessary to pay their rent or buy their freedom from servitude, pay their doctor or apothecary bill. For the California Indian, everything centers on food and clothing. With these two necessities the missions were well provided through agriculture and livestock breeding. They could, considering the standards of the native, give them all the help they needed. There was no other use for the surplus than to adorn the churches, to make the service of the Lord impressive and dignified, and to console the servants of the Church through the greater honor of their God and through the edification of their fellow men.

Finally, because I have spoken several times of "bread" in this little work, I must make it clear to the reader that I did not speak of bread made of wheat or corn flour, but of little pancakes made of corn meal. The corn is lightly boiled, then ground by hand between two stones. The meal is formed into thin, flat, little cakes, made warm over a hot iron plate. These pancakes are eaten by all the people in all America, and are served like warm bread with meat and other foods. I found them a healthful food and very pleasing to the taste after having eaten them for several weeks.