Nightmare and the Horror Film

Before beginning this "unholy" task, some qualifications are necessary. Throughout this article I will slip freely between examples drawn from horror

films and science fiction films. Like many connoisseurs of science fiction literature, I think that, historically, movie science fiction has evolved as a subclass of the horror film. That is, in the main, science fiction films are monster films, rather than explorations of grand themes like alternate societies or alternate technologies.

Secondly, I am approaching the horror/science fiction film in terms of a psychoanalytic framework, though I do not believe that psychoanalysis is a hermeneutic method that can be applied unproblematically to any kind of film or work of art. Consequently, the adoption of psychoanalysis as an interpretive tool in a given case should be accompanied by a justification for its use in regard to that case. And in this light, I would argue that it is appropriate to use psychoanalysis in relation to the horror film because within our culture the horror genre is explicitly acknowledged as a vehicle for expressing psychoanalytically significant themes such as repressed sexuality, oral sadism, necrophilia, etc. Indeed, in recent films, such as Jean Rollin's Le Frisson des Vampires and La Vampire Nue , all concealment of the psychosexual subtext of the vampire myth is discarded. We have all learned to treat the creatures of the night—like werewolves—as creatures of the id, whether we are spectators or film-makers. As a matter of social tradition, psychoanalysis is more or less the lingua franca of the horror film and thus the privileged critical tool for discussing the genre. In fact horror films often seem to be little more than bowdlerized, pop psychoanalysis, so enmeshed is Freudian psychology with the genre.

Nor is the coincidence of psychoanalytic themes and those of the horror genre only a contemporary phenomenon. Horror has been tied to nightmare and dream since the inception of the modern tradition. Over a century before the birth of psychoanalysis Horace Walpole wrote of The Castle of Otranto ,

I waked one morning, in the beginning of last June, from a dream, of which all I could recover was, that I had thought myself in an ancient castle (a very natural dream for a head like mine filled with Gothic story) and that on the uppermost bannister of a great staircase I saw a gigantic hand in armour. In the evening I sat down, and began to write, without knowing in the least what I intended to say or relate. The work grew on my hands and I grew so fond of it that one evening, I wrote from the time I had drunk my tea, about six o'clock, till half an hour after one in the morning, when my hands and fingers were so weary that I could not hold the pen to finish the sentence.

The assertion that a given horror story originated as a dream or nightmare occurs often enough that one begins to suspect that it is something akin to invoking a muse (or an incubus or succubus, as the case may be). Mary Shelley's

Frankenstein , Bram Stoker's Dracula , and Henry James's "The Jolly Corner" are all attributed to fitful sleep as is much of Robert Louis Stevenson's output—notably Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde .[2] In what sense these tales were caused by nightmares or modeled on dreams is less important than the fact that the nightmare is a culturally established framework for presenting and understanding the horror genre. And this makes the resort to psychoanalysis unavoidable.

A central concept in Jones's treatment of the imagery of nightmare is conflict. The products of the dreamwork are often simultaneously attractive and repellent insofar as they function to enunciate both a wish and its inhibition. Jones writes, "The reason why the object seen in a Nightmare is frightful or hideous is simply that the representation of the underlying wish is not permitted in its naked form so that the dream is a compromise of the wish on the one hand and on the other of the intense fear belonging to the inhibition."[3] The notion of the conflict between attraction and repulsion is particularly useful in considering the horror film, as a corrective to alternate ways of treating the genre. Too often, writing about this genre only emphasizes one side of the imagery. Many journalists will single-mindedly underscore only the repellent aspects of a horror film—rejecting it as disgusting, indecent, and foul. Yet this tack fails to offer any account of why people are interested in seeing such exercises.

On the other hand, defenders of the genre or of a specific example of the genre will often indulge in allegorical readings that render their subjects wholly appealing and that do not acknowledge their repellent aspects. Thus, we are told that Frankenstein is really an existential parable about man thrown-into-the-world, an "isolated sufferer."[4] But if Frankenstein is part Nausea , it is also nauseating. Where in the allegorical formulation can we find an explanation for the purpose of the unsettling effect of the charnel-house imagery? The dangers of this allegorizing/valorizing tendency can be seen in some of the work of Robin Wood, the most vigorous champion of the contemporary horror film. Sisters , he writes, "analyzes the ways in which women are oppressed within patriarchal society on two levels which one can define as professional (Grace) and the psychosexual (Danielle/Dominque)."[5]

One wants to say "perhaps but . . ." Specifically, what about the unnerving, gory murders and the brackish, fecal bond that links the Siamese twins? Horror films cannot be construed as completely repelling or completely appealing. Either outlook denies something essential to the form. Jones's use of the concept of conflict in the nightmare to illuminate the symbolic portent of the monsters of superstition, therefore, suggests a direction of research into the study of the horror film which accords with the genre's unique combination of repulsion and delight.

To conclude my qualifying remarks, I must note that as a hardline Freudian, Jones suffers from one important liability; he over-emphasizes the degree to

which incestuous desires shape the conflicts in the nightmare (and, by extension, in the formation of fantastic beings) and he claims that nightmares always relate to the sexual act.[6] As John Mack has argued, this perspective is too narrow; "the analysis of nightmares regularly leads us to the earliest, most profound, and inescapable anxieties and conflicts to which human beings are subject: those involving destructive aggression, castration, separation and abandonment, devouring and being devoured, and fear regarding loss of identity and fusion with the mother."[7] Thus, modifying Jones, we will study the nightmare conflicts embodied in the horror film as having broader reference than simply sexuality.

Our starting hypothesis is that horror film imagery, like that of the nightmare, incarnates archaic, conflicting impulses. Furthermore, this assumption orients inquiry, leading us to review horror film imagery with an eye to separating out thematic strands that represent opposing attitudes. To clarify what is involved in this sort of analysis, an example is in order.

When The Exorcist first opened, responses to it were extreme. It was denounced as a new cultural low at the same time that extra theaters had to be found in New York, Los Angeles, and other cities to accommodate the overflow crowds. The imagery of the film touched deep chords in our national psyche. The spectacle of possession addressed and reflected profound fears and desires never before explored in film. The basic infectious terror in the film is that personal identity is a frail thing, easily lost. Linda Blair's Regan, with her "tsks" and her "ahs," is a model of middle-class domesticity, a vapid mask quickly engulfed by repressed powers. The character is not just another evil child in the tradition of The Bad Seed . It is an expression of the fear that beneath the self we present to others are forces that can erupt to obliterate every vestige of self-control and personal identity.

In The Exorcist , the possibility of the loss of self is greeted with both terror and glee. The fear of losing self-control is great, but the manner in which that loss is manifested is attractive. Once possessed, Regan's new powers, exhibited in hysterical displays of cinematic pyrotechnics, act out the imagery of infantile beliefs in the omnipotence of the will. Each grisly scene is a celebration of infantile rage. Regan's anger cracks doors and ceilings and levitates beds. And she can deck a full-grown man with a flick of a wrist. The audience is aghast at her loss of self-control, which begins fittingly enough with her urinating on the living room rug, but at the same time its archaic beliefs in the metaphysical prowess of the emotions are cinematically confirmed. Thought is given direct causal efficacy. Regan's feelings know no bounds; they pour out of her, tearing her own flesh apart with their intensity and hurling people and furniture in every direction. Part of the legacy of The Exorcist to its successors—like Carrie, The Fury , and Patrick , to name but a few titles in this rampant subgenre—is the fascination with telekinesis, which is nothing but a cinematic

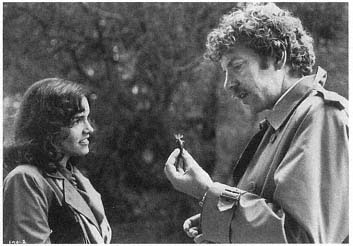

"Figures that are simultaneously attractive and replusive":

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde .

metaphor of the unlimited power of repressed rage. The audience is both drawn to and repelled by it—we recognize such rage in ourselves and superstitiously fear its emergence, while simultaneously we are pleased when we see a demonstration, albeit fictive, of the power of that rage.[8]

Christopher Lasch has argued that the neurotic personality of our time vacillates between fantasies of self-loathing and infantile delusions of grandeur.[9] The strength of The Exorcist is that it captures this oscillation cinematically. Regan, through the machinations of Satan, is the epitome of self-hatred and self-degradation—a filthy thing, festering in its bed, befoulling itself, with fetid breath, full of scabs, dirty hair, and a complexion that makes her look like a pile of old newspapers.

The origins of this self-hatred imagery are connected with sexual themes. Regan's sudden concupiscence corresponds with a birthday, presumably her thirteenth. There are all sorts of allusions to masturbation: not only does Regan misuse the crucifix, splattering her thighs with blood in an act symbolic

of both loss of virginity and menstruation, but later her hands are bound (one enshrined method for stopping "self-abuse") and her skin goes bad (as we were all warned it would). Turning the head 360 degrees also has sexual connotations; in theology, it is described as a technique Satan uses when sodomizing witches. Regan incarnates images of worthlessness, of being virtually trash, in a context laden with sex and self-laceration. But the moments of self-degradation give way to images that express delusions of grandeur as she rocks the house in storms of rage. She embodies moods of guilt and rebellion, of self-loathing and omnipotence that speak to the Narcissus in each of us.

The fantastic beings of horror films can be seen as symbolic formations that organize conflicting themes into figures that are simultaneously attractive and repulsive. Two major symbolic structures appear most prominent in this regard: fusion, in which the conflicting themes are yoked together in one, spatio-temporally unified figure; and fission, in which the conflicting themes are distributed—over space or time—among more than one figure.

Dracula, one of the classic film monsters, falls into the category of fusion. In order to identify the symbolic import of this figure we can begin with Jones's account of vampires—since Dracula is a vampire—but we must also amplify that account since Dracula is a very special vampire. According to Jones, the vampires of superstition have two fundamental constituent attributes: revenance and blood sucking. The mythic, as opposed to movie, vampire first visits its relatives. For Jones, this stands for the relatives' longing for the loved one to return from the dead. But the figure is charged with terror. What is fearful is blood sucking, which Jones associates with seduction. In short, the desire for an incestuous encounter with the dead relative is transformed, through a form of denial, into an assault-attraction, and love metamorphoses into repulsion and sadism. At the same time, via projection, the living portray themselves as passive victims, imbuing the dead with a dimension of active agency that permits the "victim" pleasure without blame. Lastly, Jones not only connects blood sucking with the exhausting embrace of the incubus but with a regressive mixture of sucking and biting characteristic of the oral stage of psychosexual development. By negation—the transformation of love to hate, by projection—through which the desired dead become active, and the desiring living passive, and by regression—from genital to oral sexuality, the vampire legend gratifies incestuous and necrophiliac desires by amalgamating them in a fearsome iconography.

The vampire of lore and the Dracula figure of stage and screen have several points of tangency, but Dracula also has a number of distinctive attributes. Of necessity, Dracula is Count Dracula. He is an aristocrat; his bearing is noble; and, of course, through hypnosis, he is a paradigmatic authority figure. He is commanding in both senses of the word. Above all, Dracula demands obedience

of his minions and mistresses. He is extremely old—associated with ancient castles—and possessed of incontestable strength. Dracula cannot be overcome by force—he can only be outsmarted or outmaneuvered; humans are typically described as puny in comparison to him. At times, Dracula is invested with omniscience, observing from afar the measures taken against him. He also hoards women and is a harem master. In brief, Dracula is a bad father figure, often balanced off against Van Helsing. who defends virgins against the seemingly younger, more vibrant Count. The phallic symbolism of Dracula is hard to miss—he is aged, buried in a filthy place, impure, powerful, and aggressive.

The contrast with Van Helsing immediately suggests another cluster of Dracula's attributes. He does appear the younger of the two specifically because he represents the rebellious son at the same time that he is the violent father. This identification is achieved by means of the Satanic imagery that contributes to Dracula's persona. Dracula is the Devil—one film in fact refers to him in its title as the "Prince of Darkness." With few exceptions, Dracula is depicted as eternally uncontrite, bent on luring hapless souls. Most importantly, Dracula is a modern devil, which, as Jones points out, means that he is a rival to God. Religiously, Dracula is presented as a force of unmitigated evil. Dramatically, this is translated into a quantum of awesome will or willfulness, often flexed in those mental duels with Van Helsing. Dracula, in part, exists as a rival to the father, as a figure of defiance and rebellion, fulfilling the oedipal wish via a hero of Miltonic proclivities. The Dracula image, then, is a fusion of conflicting attributes of the bad (primal) father and the rebellious son which is simultaneously appealing and forbidding because of the way it conjoins different dimensions of the oedipal fantasy.

The fusion of conflicting tendencies in the figure of the monster in horror films has the dream process of condensation as its approximate psychic prototype. In analyzing the symbolic meaning of these fusion figures our task is to individuate the conflicting themes that constitute the creature. Like Dracula, the Frankenstein monster is a fusion figure, one that is quite literally a composite. Mary Shelley first dreamed of the creature at a time in her life fraught with tragedies connected with childbirth.[10] Victor Frankenstein's creation—his "hideous progeny"—is a gruesome parody of birth; indeed, Shelley's description of the creature's appearance bears passing correspondences to that of a newborn—its waxen skin, misshapen head, and touch of jaundice. James Whale's Frankenstein also emphasizes the association of the monster with a child; its walk is unsteady and halting, its head is outsized and its eyes sleepy. And in the film, though not in the novel, the creature's basic cognitive skills are barely developed; it is mystified by fire and has difficulty differentiating between little girls and flowers. The monster in one respect is a child and its creation is a birth that is presented as ghastly. At the same time, the monster is made of

waste, of dead things, in "Frankenstein's workshop of filthy creation." The excremental reference is hardly disguised. The association of the creature with waste implies that, in part, the story is underwritten by the infantile confusion over the processes of elimination and reproduction. The monster is reviled as heinous and as unwholesome filth, rejected by its creator—its father—perhaps in a way that reorchestrated Mary Shelley's feelings of rejection by her father, William Godwin.

But these images of loathesomeness are fused with opposite qualities. In the film myth, the monster is all but omnipotent (it can function as a sparring partner for Godzilla), indomitable, and, for all intents and purposes, immortal (perhaps partly for the intent and purpose of sequels). It is both helpless and powerful, worthless and godlike. Its rejection spurs rampaging vengeance, combining fury and strength in infantile orgies of rage and destruction. Interestingly, in the novel this ire is directed against Victor Frankenstein's family. And even in Whale's 1931 version of the myth the monster's definition as outside (excluded from a place in) the family is maintained in a number of ways: the killing of Maria; the juxtaposition of the monster's wandering over the countryside with wedding preparations; and the opposition of Frankenstein's preoccupation with affairs centered around the monster to the interest of propagating an heir to the family barony. The emotional logic of the tale proceeds from the initial loathesomeness of the monster, which triggers its rejection, which causes the monster to explode in omnipotent rage over its alienation from the family, which, in turn, confirms the earlier intimation of "badness," thereby justifying the parental rejection.[11] This scenario, moreover, is predicated on the inherently conflicting tendencies—of being waste and being god—that are condensed in the creature from the start. It is, therefore, a necessary condition for the success of the tale that the creature be repellent.

One method for composing fantastic beings is fusion. On the visual level, this often entails the construction of creatures that transgress categorical distinctions such as inside/outside, insect/human, flesh/machine, etc.[12] The particular affective significance of these admixtures depends to a large extent on the specific narrative context in which they are embedded. But apart from fusion, another means for articulating emotional conflicts in horror films is fission. That is, conflicts concerning sexuality, identity, aggressiveness, etc. can be mapped over different entities—each standing for a different facet of the conflict—which are nevertheless linked by some magical, supernatural, or sci-fi process. The type of creatures that I have in mind here include doppelgängers , alter-egos, and werewolves.

Fission has two major modes in the horror film.[13] The first distributes the conflict over space through the creation of doubles, e.g., The Portrait of Dorian Gray, The Student of Prague , and Warning Shadows . Structurally, what is involved in spatial fission is a process of multiplication, i.e., a charac-

Bride of Frankenstein: Elsa Lanchester and Boris Karloff

ter or set of characters is multiplied into one or more new facets each standing for another aspect of the self, generally one that is either hidden, ignored, repressed, or denied by the character who has been cloned. These examples each employ some mechanism of reflection—a portrait, a mirror, shadows—as the pretext for doubling. But this sort of fission figure can appear without such devices. In I Married a Monster from Outer Space , a young bride begins to suspect that her new husband is not quite himself. Somehow he's different than the man she used to date. And she's quite right. Her boyfriend was kidnapped by invaders from outer space on his way back from a bachelor party and was replaced by an alien duplicate. This double, however, initially lacks feelings—the essential characteristic of being human in fifties sci-fi films—and his bride intuits this. The basic story, sci-fi elements aside, resembles a very specific paranoid delusion called Capgras syndrome. The delusion involves the patient's belief that his or her parents, lovers, etc. have become minatory doppelgängers . This enables the patient to deny his fear or hatred of a loved one by splitting the loved one in half, creating a bad version (the invader) and a good one (the victim). The new relation of marriage in I Married a Monster appears to engender a conflict, perhaps over sexuality, in the wife which is expressed through the fission figure.[14] Splitting as a psychic trope of denial is the root prototype for spatial fission in the horror film, organizing conflict through the multiplication of characters.

Fission occurs in horror films not only in terms of multiplication but also in terms of division. That is, a character can be divided in time as well as multiplied in space. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and the various werewolves, cat

people, gorgons, and other changelings of the genre are immediate examples. In the horror film, temporal fission—usually marked by shape changing—is often self-consciously concerned with repression. In Curse of the Werewolf one shot shows the prospective monster behind the bars of a wine cellar window holding a bottle; it is an icon of restrained delirium. The traditional conflict in these films is sexuality. Stevenson's Jekyll and Hyde is altered in screen variants so that the central theme of Hyde's brutality—which I think is connected to an allegory against alcoholism in the text—becomes a preoccupation with lechery. Often changeling films, like The Werewolf of London or The Cat People , eventuate in the monster attacking its lover, suggesting that this subgenre begins in infantile confusions over sexuality and aggression. The imagery of werewolf films also has been associated with conflicts connected with the bodily changes of puberty and adolescence: unprecedented hair spreads over the body, accompanied by uncontrollable, vaguely understood urges leading to puzzlement and even to fear of madness.[15] This imagery becomes especially compelling in The Wolfman , where the tension between father and son mounts through anger and tyranny until at last the father beats the son to death with a silver cane in a paroxysm of oedipal anxiety.[16]

Fusion and fission generate a large number of the symbolic biologies of horror films, but not all. Magnification of power or size—e.g., giant insects (and other exaggerated animalcules)—is another mode of symbol formation. Often magnification takes a particular phobia as its subject and, in general, much of this imagery seems comprehensible in terms of Freud's observation that "the majority of phobias . . . are traceable to such a fear on the ego's part of the demands of the libido."[17]

Giant insects are a case in point. The giant spider, for instance, appeared in silent film in John Barrymore's Jekyll and Hyde as an explicit symbol of desire. Perhaps insects, especially spiders, can perform this role not only because of their resemblance to hands—the hairy hands of masturbation—but also because of their cultural association with impurity.[18] At the same time, their identification as poisonous and predatory—devouring—can be mobilized to express anxious fantasies over sexuality. Like giant reptiles, giant insects are often encountered in two specific contexts in horror films. They inhabit negative paradises—jungles and lost worlds—that unaware humans happen into, not to find Edenic milk and honey but the gnashing teeth or mandibles of oral regression. Or, giant insects or reptiles are slumbering potentials of nature released or awakened by physical or chemical alterations caused by human experiments in areas of knowledge best left to the gods. Here, the predominant metaphor is that these creatures or forces have been unfettered or unleashed, suggesting their close connection with erotic impulses. Like the fusion and fis-

sion figures of horror films, these nightmares are also explicable as effigies of deep-seated, archaic conflicts.

So far I have dwelt on the symbolic composition of the monsters in horror films, extrapolating from the framework set out by Jones in On the Nightmare in the hope of beginning a crude approximation of a taxonomy. But before concluding, it is worthwhile to consider briefly the relevance of archaic conflicts of the sort already discussed to the themes repeated again and again in the basic plot structures of the horror film.[19]

Perhaps the most serviceable narrative armature in the horror film genre is what I call the Discovery Plot. It is used in Dracula, The Exorcist, Jaws I & II, It Came From Outer Space, Curse of the Demon, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, It Came From Beneath the Sea , and myriad other films. It has four essential movements. The first is onset: the monster's presence is established, e.g., by an attack, as in Jaws . Next, the monster's existence is discovered by an individual or a group, but for one reason or another its existence or continued existence, or the nature of the threat it actually poses, is not acknowledged by the powers that be. "There are no such things as vampires," the police chief might say at this point. Discovery, therefore, flows into the next plot movement, which is confirmation. The discoverers or believers must convince some other group of the existence and proportions of mortal danger at hand. Often this section of the plot is the most elaborate, and suspenseful. As the UN refuses to accept the reality of the onslaught of killer bees or invaders from Mars, precious time is lost, during which the creature or creatures often gain power and advantage. This interlude also allows for a great deal of discussion about the encroaching monster, and this talk about its invulnerability, its scarcely imaginable strength, and its nasty habits endows the off-screen beast with the qualities that prime the audience's fearful anticipation. Language is one of the most effective ingredients in a horror film and I would guess that the genre's primary success in sound film rather than silent film has less to do with the absence of sound effects in the silents than with the presence of all that dialogue about the unseen monster in the talkies.

After the hesitations of confirmation, the Discovery Plot culminates in confrontation. Mankind meets its monster, most often winning, but on occasion, like the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers , losing. What is particularly of interest in this plot structure is the tension caused by the delay between discovery and confirmation. Thematically, it involves the audience not only in the drama of proof but also in the play between knowing and not knowing,[20] between acknowledgment versus nonacknowledgment, that has the growing awareness of sexuality in the adolescent as its archetype. This conflict can become very pronounced when the gainsayers in question—generals, police

Donald Sutherland in the toils of the delayed-discovery plot:

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

chiefs, scientists, heads of institutions, etc.—are obviously parental authority figures.

Another important plot structure is that of the Overreacher. Frankenstein, Jekyll and Hyde , and Man with the X-Ray Eyes are all examples of this approach. Whereas the Discovery Plot often stresses the short-sightedness of science, the Overreacher Plot criticizes science's will to knowledge. The Overreacher Plot has four basic movements. The first comprises the preparation for the experiment, generally including a philosophical, popular-mechanics explanation or debate about the experiment's motivation. The overreacher himself (usually Dr. Soandso) can become quite megalomaniacal here, a quality commented upon, for instance, by the dizzyingly vertical laboratory sets in Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein . Next comes the experiment itself, whose partial success allows for some more megalomania. But the experiment goes awry, leading to the destruction of innocent victims and/or to damage or threat to the experimenter or his loved ones. At this point, some overreachers renounce their blasphemy; the ones who don't are mad scientists. Finally, there is a confrontation with the monster, generally in the penultimate scene of the film.

The Overreacher Plot can be combined with the Discovery Plot by making the overreacher and/or his experiments the object of discovery and confirmation. This yields a plot with seven movements—onset, discovery, confirmation, preparation for the experiment, experimentation, untoward consequences, and confrontation.[*] But the basic Overreacher Plot differs thematically from

Confirmation as well as discovery may come after or between the next three movements in this structure.

the Discovery Plot insofar as the conflicts central to the Overreacher Plot reside in fantasies of omniscience, omnipotence, and control. The plot eventually cautions against these impulses but not until it gratifies them with partial success and a strong dose of theatrical panache.

In suggesting that the plot structures and fantastic beings of the horror film correlate with nightmares and repulsive materials, I do not mean to claim that horror films are nightmares. Structurally, horror films are far more rationally ordered than nightmares, even in extremely disjunctive and dreamlike experiments like Phantasm . Moreover, phenomenologically, horror film buffs do not believe that they are literally the victims of the mayhem they witness whereas a dreamer can quite often become a participant and a victim in his/her dream. We can and do seek out horror films for pleasure, while someone who looked forward to a nightmare would be a rare bird indeed. Nevertheless, there do seem to be enough thematic and symbolic correspondences between nightmare and horror to indicate the distant genesis of horror motifs in nightmare as well as significant similarities between the two phenomena. Granted, these motifs become highly stylized on the screen. Yet, for some, the horror film may release some part of the tensions that would otherwise erupt in nightmares. Perhaps we can say that horror film fans go to the movies (in the afternoon) perchance to sleep (at night).