The Mixtures of Rooming House Streets

Work places and rooming houses were inextricably linked. Especially during boom times, employers needed a ready supply of help on short notice, and workers could afford only so much time and money for their journey to work. Given the erratic availability of employment, they also needed to be within easy reach of many different companies. Roomers rarely owned cars. Thus, rooming house areas were usually within half a mile of varied jobs. For the greatest number of rooming house residents, work was downtown in the retail shopping district in the office core, or in a warehouse, shipping, or manufacturing zone very close to the center of the city. Higher-paid white-collar workers could afford to commute on streetcars to an outlying rooming house area (fig. 4.13). Streetcar transfer locations like these were exceptions to the dominant pattern, but made up between 5 and 10 percent of San Francisco's rooming house supply by 1930.[53]

Rooming houses might have seemed unnecessary to downtown, but they were just as essential for urban economic growth as the family tenements that stretched next to factories and just as basic as the new downtown skyscrapers and loft buildings. At the turn of the century, urban Americans knew at least two different types of rooming house areas: districts of old-house rooming houses, and newer purpose-built rooming house districts.

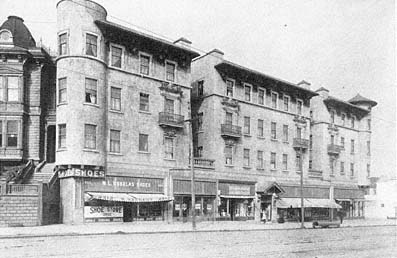

Figure 4.13

A large outlying rooming house in San Francisco, photographed ca. 1912.

Streetcars to downtown ran directly past the building. Note entrance to hotel

under the small gable roof in the center of the storefronts.

A large central area of San Francisco known as the Western Addition was a quintessential old-house rooming district. Fillmore Street was its commercial and entertainment spine (fig. 4.14).[54] The Western Addition was a twenty-minute walk west of downtown. Between downtown and the Western Addition was a neighborhood of newer flats and houses with higher rents, an area rebuilt after the fire of 1906. Several major streetcar lines crossed the Western Addition on their way farther west to single-family neighborhoods. By the 1920s, Fillmore Street's vaudeville houses, dance halls, and inexpensive restaurants were well known in San Francisco. After the fire, many downtown entrepreneurs had relocated along the street. From the public experience of this main artery, the whole Western Addition was most commonly known as "the Fillmore," although the street itself was off-center, near the edge of the neighborhood (fig. 4.15). Most of the area was filled with former middle-income houses and flats, most built in wood between 1870 and 1900, the later ones using wildly exuberant Victorian ornamentation. Commercial land-use mixture in the Western Addition was common. Owners had built long rows of storefronts into the base of houses or flats and leased them to corner grocery stores, tobacconists, bars, millinery shops, secondhand stores, and antique shops. On the side streets were auto dealers, repair shops, and commercial laundries that stood next to housing and were important employers in the neighborhood (fig. 4.16). Along the major avenues were other employers. At the southeastern corner of the district, the postfire city hall and civic center office complex offered nearby white-collar employment.[55]

Figure 4.14

Map of two principal rooming house districts in

San Francisco. Streets running north and south

(vertically) are, from left to right, Divisadero,

Fillmore, and Van Ness. The diagonal is Market Street.

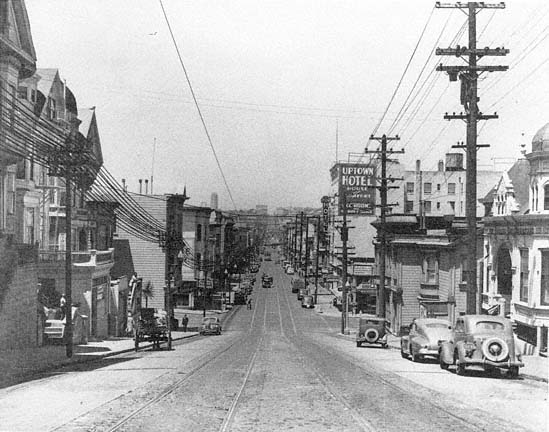

Figure 4.15

Residential section of Fillmore Street in 1944. Seen looking north from Grove Street, this view was

typical of the southern edge of the Western Addition.

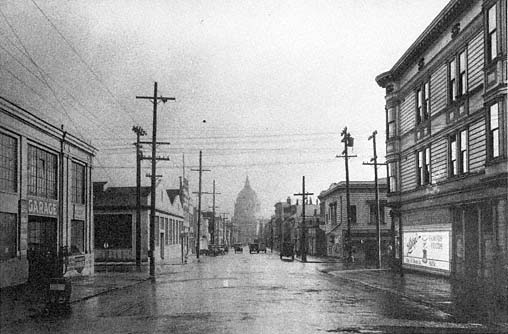

Figure 4.16

Side street in the Western Addition in the 1920s. Laundries and industrial shops mixed with

older flats, many rented as rooming houses.

To people from the newer, richer family districts of San Francisco, the streets of the Western Addition epitomized mixture, crude commercialism, and unskilled employment. Many of the commercial building fronts were jerry-built. The housing and commercial spaces were built of wood and rarely faced with masonry, as were the areas closer to downtown. The district represented reuse, the filtering of blocks to new tenants. In the late 1950s, when Alfred Hitchcock looked for an old rooming house setting for a mysterious transitional character in Vertigo , he found what he needed on the southern edge of the Western Addition.[56]

The Western Addition was also known for its social, ethnic, and racial diversity. After the fire, inexpensive rooms of the Western Addition became home for a growing number of German, Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants, along with more consolidated settlement patterns of Japanese and African-American families who had been living in dispersed patterns before the fire.[57] At the end of the depression, San Francisco's Real Property Survey documented race on a unit-by-unit basis, showing that at the eastern edge of the Western Addition African-American families were mixed with Japanese, Filipino, and European families. The 1940 census showed that the city's 5,000 blacks

Figure 4.17

Ellis Street in the Tenderloin district, San Francisco, in the early 1940s. Buildings of one-room and

two-room apartments are interspersed next to tall residential hotels.

made up less than 1 percent of the city's population; in the Western Addition, African-Americans comprised 5 percent and by 1960 would comprise half the residents in the area.[58] Most cities had a zone of converted houses with a succession similar to the Western Addition. In Boston, it was the South End; in New York, Chelsea came to be a zone of converted houses; in Chicago, it was the Near North Side.

An adjacent San Francisco area, the Tenderloin district, exemplified another type of rooming precinct—a rebuilt rooming house area that was overwhelmingly white as late as 1970.[59] The Tenderloin is essentially bounded on the west by the Western Addition and on the north by Nob Hill, and it is immediately west of the department stores around Union Square. By the 1920s, most cities had two or three such areas, some of them only a few blocks in extent. Such areas were not composed of old converted houses but new urbane buildings expressly intended as rooming houses, often next to middle-income apartments and midpriced hotels (fig. 4.17). If a single 100-room hotel had represented the social stratification of the hotels in the Tenderloin in 1930, 52 of the rooms would have been of the rooming house type; 26, midpriced; and 22, the cheap lodging house type. The Tenderloin typified a rebuilt rooming house area also in that along one side (the Nob Hill

Figure 4.18

The bright light district on Fillmore Street in the 1920s. After the fire of 1906, Fillmore became one of the

substitutes for the burned Market Street. The corner light fixtures added a festival air to the street year-round.

side), it had expensive apartments and houses; and on the opposite side (the South of Market) was a huge district of working-class housing. The newness of the Tenderloin in the 1920s was a result of the rebuilding required after San Francisco's 1906 fire. Even without such a stimulus, however, landowners in other cities had found the same rebuilding necessary and profitable. In 1930, the Tenderloin had 59 percent of San Francisco's rooming house units. All of the new rooming house districts, together, had a third of the city's residential hotel rooms.[60]

For roomers in any type of rooming house district, a short journey to play was as important as a short journey to work. Rooming house areas relied on thoroughfares with heavy streetcar or bus service and commercial businesses that catered to people from throughout the city. In San Francisco, prime examples were Fillmore and Market streets. Like the thoroughfares that cut through the bright light districts of other cities, Market and Fillmore were busy at night with people going out to eat and be entertained at the theaters, vaudeville houses, movie halls, and large dance halls—the latter being prominent and often on the second floor above retail stores.[61] Inexpensive restaurants, cafeterias, bars or lounges, and variety stores filled the interstices (fig. 4.18).

Above the larger men's clothing stores were often pool halls. As one commentator put it, in such an area the clothing store signs always advertised for "gents," never for "men" or "gentlemen."[62] These bright light entertainments and retail bargains depended more on people from outside the rooming house zone than from inside it. Local residents relied more on smaller stores scattered throughout the zone: small bakeries, tailor shops, laundries, drugstores, shoe repair shops, and also (depending on the decade and local state law) corner liquor stores that also sold convenience food and snacks at exorbitant prices.[63] Nearest the workers' cottage or tenement districts were usually a few goodsized public bathhouses so essential for tenants who had hot water only once a week.[64] At the sleaziest or least expensive side of the rooming house area, but never far from the main thoroughfare, one would see astrologers' parlors, saloons, and fairly obvious houses of prostitution. No matter where one traveled in the rooming house zone, however, there were restaurants of all descriptions. Their role was central to the residents of the area.