Selective Elimination

Castanea and Ulmus , North American Forests

(Anagnostakis 1982; McCormick and Platt 1980; Strobel and Lanier 1981)

As in many genera of northern hemisphere trees, Castanea and Ulmus are represented by different species in eastern North America, eastern Asia, and Europe. The Chinese chestnut, C. mollisima , and the Chinese and Siberian elms, U. parvifolia and U. pumila , evidently coevolved with parasitic Ascomycetes, the chestnut blight, Endothia parasitica , and the Dutch elm disease, Ceratocystis ulmi . Both fungi invade wounds in the bark and their mycelia grow through the living vascular tissues. On the Asiatic host trees,

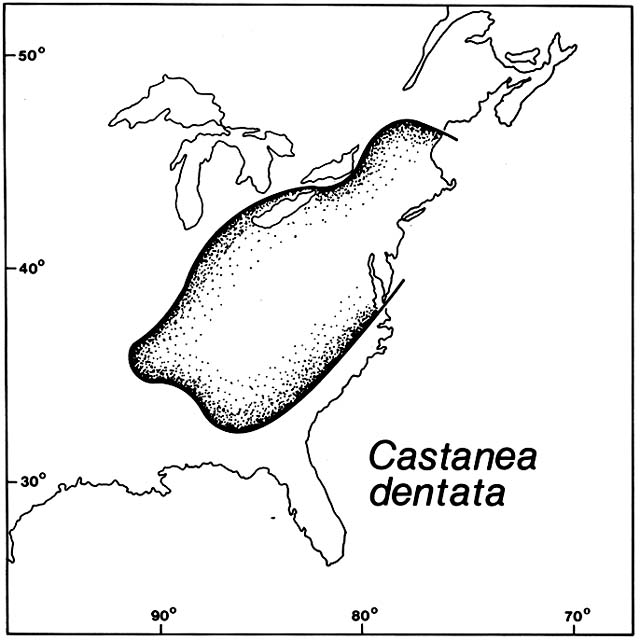

Figure 5. Castanea dentata . The former range of the North American Castanea is shown here before it was

eliminated from the forests by the chestnut blight (adapted from Stevens, 1917). This fungus evolved as a mild

parasite of the Chinese chestnut, following the rule that a successful parasite does not exterminate its host. It

did not follow this rule in North America where it arrived in 1904 with imported Chinese chestnut trees. Its

windborn spores rapidly infected the whole American chestnut population.

the symptoms are mild; on congeneric hosts elsewhere, infection with the fungi is catastrophic.

Chestnut blight arrived in New York in 1904 on Chinese chestnut trees imported as ornamentals for planting in the Bronx Zoological Garden. The spores of the fungus are wind-borne and soon infected the native Castanea dentata , an important member of the hardwood forests over several million hectares of the eastern United States (fig. 5). The tree was valued as a fine hardwood timber, for tanbark, and for the edible nuts. When the trees began dying back on a grand scale, expensive efforts to control the disease were begun. It soon became obvious that there was no hope of stopping the spread of the fungus throughout the range of the host. Attempts to transfer resistance from the Chinese to the American chestnut by standard hybridization and breeding methods were frustrated by the fact that resistant hybrids were ecologically different from their American parent. If introduced to the forests, they would have competed with other native hardwoods rather than reoccupying the chestnut's niche.

Castanea dentata is not extinct in eastern North America because the root systems of trees that have died back continue to send up sprouts, but these are reinfected and killed back again before reaching tree size or reproducing.

Chestnut blight arrived in northern Italy in 1938 and soon spread widely on the European species, Castanea sativa . The situation differed from that in North America in that European chestnut trees are generally planted, commonly as regular orchards, rather than being members of a natural forest. The species was evidently introduced westward from its southeastern European homeland during classic Roman times.

Beginning in 1951, some of the European chestnut trees that had been diseased began to recover; evidently the fungus was being attacked by a disease of its own that reduced its virulence. Research is now aimed at practical methods of spreading this viruslike disease of Endothia and perhaps saving both Castanea sativa and C. dentata .

Dutch elm disease caused by the fungus Ceratocystis , arrived in Europe, by unknown means, before it reached North America. There are several susceptible Ulmus species in both regions. Ceratocystis was first noted in the Netherlands in 1919, soon after in France and Belgium, and by 1927 in England. The fungus is spread by bark beetles of various kinds and thus moved more slowly than the wind-borne Endothia .

Ceratocystis arrived in the eastern United States in the 1930s on elm logs imported from Europe. The native elms are important dominants in floodplain and other moist forests over a huge area. Also, Ulmus americana had been planted over an even wider area as the favorite of all street trees. By 1950 rural and urban elms were dying wholesale from Quebec and Vermont

west to Illinois and south to Virginia and Tennessee. Spread of the fungus was slowed in some urban areas by expensive removal of diseased trees and constant spraying of beetles, but nothing could stop the mortality of forest elms. During the 1950s and 1960s, the fungus spread northeastward into Maine, southeastward into the Deep South and westward to the range limits of wild elms in the High Plains. Beyond there, it spread in town elms through the northern Rockies, reaching Oregon in 1973, northern California in 1975, and southern California in 1978, the end of the trail of elms planted by nostalgic emigrants from the east.

There is some hope of developing biological control of Ceratocystis by injecting elms with cultures of a bacterium antagonistic to the fungus, but this is more likely to save street trees than to bring back the natural stands; their roots are dead, not resprouting like chestnuts.

Panax , Eastern Asia and Eastern North America

(Emboden 1972; Price 1960)

Ginseng, Panax schinseng , has been a legendary plant in Chinese herbal medicine for millennia. Many wonderful powers have been attributed to its root, and it has generally commanded higher prices than any other herb in earth history. The species is native to the shady floor of mature hardwood forests of temperate eastern Asia. Even where uncleared relics of such forests survive, the ginseng is extinct in the wild over much of its native range. However, it has been taken into cultivation, particularly in South Korea, where tens of thousands of persons are currently employed in its production.

A related species, Panax quinquefolia , is native to undisturbed hardwood forests of eastern North America. Early in the eighteenth century, French Jesuits with experience in China organized exports of the American ginseng to China from Canada. Later, ginseng from New England became one of the most valuable cargoes the Yankee clippers had to trade with China. The roots were originally dug mainly by frontiersmen on the fringe of settlements. Later, they were dug from remnant forests, especially in the Appalachians. Not in law but in fact, wild forest ginseng became the property of the finder, regardless of whether it grew on private land, in national parks, or in nature reserves. Some root diggers left young plants and seeds for future harvest, but the species is extinct in much of its former range. Prices have continued to rise, recently to nearly $150/lb. In 1978, the U.S. Endangered Species Authority barred exports of wild ginseng from all states except Michigan, where digging was effectively controlled. Since then other states have started rigorous controls and resumed licensed exports. In 1979, U.S. exports of wild ginseng were valued at about $5 million. Meanwhile cultivation has

begun, mainly based on the Chinese species, which is reported to have been planted in natural forest habitats in the Blue Ridge Mountains once occupied by the American species. U.S. exports of cultivated ginseng in 1979 were valued at about $15 million.

Comment

There are other plants like ginseng that people have sought out individually because of their high value and have exterminated from parts of the original ranges. For example, for centuries extravagant prices have been paid for wood of two unrelated tropical trees, lignum vitae or gayac, Guaiacum officinale , and false gayac, Intsia bijuga . Their woods are among the strongest and hardest known and are also used as a cure for syphilis. Lignum vitae has been eliminated from some of its native dry West Indian forests. False gayac has been eliminated from some Indo-Pacific coastal forests. For example, in the Seychelles it is apparently extinct, and efforts at reintroduction have failed.

When a species is known to be rare, it is especially attractive to plant collectors, including academic botanists. In the Atlas of the British Flora, dots showing locations of very rare species are slightly displaced to frustrate collecting.

Conceivably, introduced insects might selectively eliminate plant species in their native regions in the same fashion that introduced fungi eliminated chestnuts and elms. However, no clear cases are known. The gypsy moth, introduced to Massachusetts in 1869, is still spreading in the United States. It prefers some host trees, for example, Quercus and Prunus , but it is not as specialized a parasite as some fungi. In 1981, the gypsy moth was credited with defoliating 10 million acres of North American forest, but the trees generally recovered and the ranges are apparently unaffected. Cases of elimination of introduced weeds by introduced insects are given in Chapter 4.