Reproduction 1: The "Objective" Character of Art

It can no longer be a matter of a plastic Beauty.

—Marcel Duchamp

Among Marcel Duchamp's ready-mades, no object has drawn more interest, controversy, and notoriety than his Fountain (fig. 48).[5] Although Duchamp had been working on ready-mades since 1913, these works were largely relegated to the privacy of his studio.[6] The controversy surrounding the exhibition of Fountain represents the first explicit encounter of the public with the idea of the ready-made.[7] In Fountain an ordinary piece of plumbing—a lavatory urinal—was chosen by Duchamp, rotated ninety degrees on its axis, set on a pedestal, and signed "R. MUTT." Submitted to the first exhibition of the American Society of Independent Artists of April, 1917, Fountain never made it past the deliberations of the hanging jury. Fountain was not exhibited because the jury was unable to recognize the aesthetic value of the work: " [The Fountain ] may be a very useful object in its place, but its place is not an art exhibition, and it is, by no definition, a work of art."[8] Consequently, this scandalous object was "suppressed" (to use Duchamp's term) by being hidden behind a partition for the rest of the exhibition, only to be retrieved later and sold to Walter Arensberg, who lost the piece while it was in his possession.

All that is left of Fountain today is the documentation surrounding a nonevent concerning a nonexisting object: Alfred Stieglitz's (1864–1946)

Fig. 48.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. (Photograph of lost

original.) Assisted ready-made: urinal turned on its back.

Version of 1964, height 24 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

famous photograph published as the cover to The Blind Man, no. 2 (May 1917), an unsigned editorial entitled "The Richard Mutt Case," and Louise Norton's "Buddha of the Bathroom."[9] There are several full-scale versions of the urinal in existence, whose status as either found objects (they have only an approximate resemblance to the photographic reproduction of the urinal), or as cast facsimiles (full size and miniature size), further modify, through reproduction, the viewer's perception of the lost "original."[10] It is important to note, however, that no subsequent urinal resembles the model photographed by Stieglitz.[11] Renamed the Madonna of the Bathroom, due to a "shadow on the urinal suggesting a veil," this image celebrates an attitude of comic irreverence.[12] The centrality and the sculptural qualities of the urinal are emphasized by its position in front of a painting. By relegating painting to mere background, this bathroom fixture assumes a formal authority that hints at a subjective presence. It is not surprising that Stieglitz's photograph of Fountain is described as looking "like anything from a Madonna to a Buddha."[13]

What is most striking about Fountain is the fact that despite the extraordinary controversies generated by the urinal, the object in question, artistic or otherwise, seems to have barely existed. Initially a mere sample

of mass-produced plumbing, the urinal was further reified through its photographic reproduction, only to come into existence après-coup, as a reproduction that replaces the original. The fact that these authorized and signed belated copies of Fountain are assessed as having significant monetary value further highlights the paradox of a work whose copies are worth more than the original. Fountain , or the drama of the urinal that pretends to be art, thus stages fundamental questions involving the relation of objects to art and value. William Camfield eloquently summarized this dilemma:

Some deny that Fountain is art but believe that it is significant for both the history of art and aesthetics. Others accept it grudgingly as art but deny that it is significant. To complete the circle, some insist that Fountain is neither art nor an object of historical consequence, while a few assert that it is both art and significant—though for utterly incompatible reasons.[14]

Camfield's assessment of the debates about the artistic value or nonvalue of Fountain outlines the impasse generated by this work. It seems that neither the status nor the significance of this object can be decided as long as the challenge that this object proposes to art is not elucidated.

The question regarding the artistic or nonartistic value of Fountain overshadows the fact that this "object" was never displayed. Its scandalous presence is evoked only by the instances of its reproduction, be it photographic or belatedly artisanal. Thus it seems that the value of the urinal is, from the very beginning, tied in with the history of the object's reproduction; that is, with the documentation surrounding the object, rather than the object itself. This emphasis on documentation should not be surprising, once we recognize Duchamp's interest in "a dry conception of art" based on his mechanical interests. Commenting on the Chocolate Grinder, Duchamp explains: "I couldn't go into the haphazard drawing or the paintings, the splashing of paint. I wanted to go back to a completely dry drawing, a dry conception of art. . .< And the mechanical drawing for me was the best form for that dry conception of art" (dmd , 130). His interest in mechanical drawing marks both his radical break with painting and his point of departure for the conceptual developments leading to the

Large Glass; such developments include the use of mechanical renderings, painted studies, and working notations (collected in The Box of 1914 ). Thus, the integration of documentation not merely as a process but as an aspect of the work of art, becomes the trademark of this "dry conception of art." The passage to the ready-mades, that is, the shift from mechanical drawing to an actual mass-produced object, thus emerges as a necessary development. Rather than prescribing the production of an object through mechanical drawing and notation, Duchamp uses documentation as a way of creating a new point of view, "a new thought for that object."[15] The role of documentation now changes: it is neither prescriptive nor descriptive, but rather, poetic. An examination of these poetics will help to elucidate the question of how Duchamp's conception of "dry art" is translated into the "wet art" of the urinal/fountain.

Before exploring this question in more detail, it is important to recall briefly the problems raised by the fact that our knowledge of Fountain is mediated solely through the documentation published in The Blind Man, no. 2. (May 1917). Given that this documentation is not merely a record but also constitutes the only knowledge that we have of this object/event, we must consider what is at stake in this strategy of delayed exposure. The set of displacements that this work actively stages includes: I) an artisanal object replaced by a mass-produced object, 2) an object replaced by a photograph, 3) Duchamp's signature replaced by the pseudonym "R. Mutt," 4) the author (Duchamp) replaced by a photographer (Stieglitz) and a woman writer (Norton), and 5) the spectator (who attends the Independents' Show, but does not see the work) replaced by The Blind Man (a document that publicly exhibits and comments on this work, which was previously not shown).[16] Each of these displacements involves a violation of the traditional criteria defining a work of art: I) the urinal is not an original object, since it is mass-produced, 2) a reproduction (photograph) is exhibited rather than the original, 3) the use of a pseudonym to sign the work raises questions of attribution, 4) it is difficult to attribute the work to a single author, since its reproduction involves other authors, and 5) the spectator does not see the original but knows the work only through its reproduction. In each of these instances one of the terms necessary to the definition of a work of art is displaced, thereby staging the impossibility of classical conditions to define the work as art.

But the history of Fountain does not end here; instead, it continues with the history of its further reproduction through full-scale versions and miniature editions. The reproductions of Fountain are haunted by a technological rather than a human fatality; the urinal chosen by Duchamp in 1917 becomes outdated—its obsolescence being the expression of its technical extinction. Having suffered a "death" of sorts, the object is approximately reassembled in several versions, each different from the other. The Fountain (1950, second version) is selected by Sidney Janis at a flea market in Paris, following Duchamp's request. The Fountain (1963, third version) is based on a urinal selected by Ülf Linde in Stockholm, later approved and re-signed by Duchamp.[17] In these cases the obsolescence of the urinal is compensated for by treating this mass-produced object as a "found" object, and by using intermediaries who act as agents, negotiating its discovery as an "already made" object.[18] There is also a fourth version of Fountain (1964), a cast facsimile edition of eight copies produced by Galleria Schwarz under Duchamp's supervision. In addition there are miniature cast facsimiles for The Box in a Valise, starting with Fountain (1938, a maquette made by Duchamp) and subsequent cast reproductions based on molds, made by different craftsmen (1938, 1940, and 1950).[19] These latter attempts at the reproduction of Fountain, in series of multiples, cannot be considered as "reincarnations of lost and destroyed objects" (as Kozloff contends) but rather as instances mimicking the processes of industrial production.

Thus, the efforts to reproduce Fountain set into motion a veritable industry: an original that is a documented copy leads to the proliferation of copies that are now documented originals. These two disparate gestures both mirror and invert one another. The first gesture involves selecting a mass-produced object and passing it off as art. The second involves the reproduction of a copy in order to produce legitimate art objects, signed by Duchamp. Both conceive the creative act in economic terms, that is, the concept of artistic value in each of these cases is tied to the reproduction of the object. In the first case, the strategy of substitutions operating on the work, the author, and the signature defers systematically the concept of originality by ascribing value not to the object itself but rather to its circulation. In the second case, the reproduction of an object now recognized as art leads to the production of serial works, thereby associating the concept

of value with the production of multiples. The supposed originality of the work of art is subverted by inscribing the work into a relay that corresponds to a set of delays. Artistic value emerges as a function of reproduction, that is, as a process of repetition that postpones the value of the work by inscribing it into the temporality of the future perfect.

If we consider the status of the urinal as a mass-produced object, additional questions arise. What kind of object is the urinal? Can we speak of it as an object in ordinary terms? Because it is mass-produced, Fountain shares with the other ready-mades the fate of being a perfect copy. Its serial reproduction through molds assures the impossibility of distinguishing it from the original; as an industrial object it is a copy with no original, so to speak. In his notes on the infrathin, Duchamp evokes the dilemma of thinking about difference in the context of mass reproduction: "The difference/ (dimensional) between/ 2 mass produced objects/ [from the same mold]/ is an infra thin/when the maximum (?)/precision is/ obtained" (Notes, 18).[20] It seems that the reproduction, and hence, repetition of the object generates an infinitesimal difference making this object more or less similar to itself. As Duchamp explains, "In Time the same object is not the/ same after a I second interval—what/ Relations with the identity principle?" (Notes, 7). By drawing the viewer's attention to the temporal dimension involved in the process of mass production, Duchamp inscribes a delay, an infrathin difference, into its principle of identity. The act of choosing the urinal, or any other ready-made, is based on the assumption that all reproduction involves a temporal dimension mediating the presence of the object. This inscription of a temporal dimension into the perception of the urinal further disrupts the immediacy of the object, just as the title Fountain sets up an incongruence between this ordinary object and the spectator's expectations.

Moreover, not only is the urinal a mold (the same mold that can generate a multitude of analogous objects) but it is also molded to the needs and body of the anonymous spectator. The shape of the urinal follows the dictates of anatomy, but in reverse order. Although it represents the quintessential male instrument, the adaptation of this receptacle to male anatomy generates the potential inscription of femininity, since its visual appearance is that of an oval receptacle.[21] This effort to reproduce the male body by molding the urinal to its shape ironically generates the literal

impression of femininity, its obverse. This double allusion to gender in the guise of femininity and masculinity can be seen as an instance of the infrathin. Duchamp defines this interval as "separation has the 2 senses male and female" (Notes , 9). Thus, eroticism appears in the object where it is least expected to be found—the urinal. It is particularly ironic that eroticism should be potentially inscribed in the gesture associated with the most sterile and precise forms of both corporeal (bodily waste) and industrial production (mass production as the generation of sameness). Reproduction in this context becomes generative, since it recontextualizes both gender and the distinction of ordinary and art objects. The notion of reproduction that Duchamp plays with redefines the nature of the aesthetic object by delaying its becoming an object proper. The interval of this delay, engendered both by the visual appearance of the object and its playful title, becomes the infrathin trace of its libidinal expression.

While Fountain shares with other ready-mades the fate of being a massproduced object, there is a way in which it remains unique. While the choice of ready-mades is based on "visual indifference" and "a total absence of good and bad taste," the urinal stands out because it is difficult to disengage this object from its physical function and its cultural connotations.[22] While Duchamp may ask rhetorically, "A urinal—who would be interested in that?," it is clear that this mass-produced object raises issues that other ready-mades do not. The isolation of this porcelain plumbing fixture on a pedestal evokes, irrevocably, its previous context and history. The urinal is traditionally kept out of sight because of its bodily associations; the evanescent odor of the urinal continues to haunt the metaphorical fountain. The urinal not only is a mass-produced object but it also serves the repeated needs of the masses. The repetition inscribed in the manufactured nature of the urinal is reiterated by its use value, the automatic sense in which it indiscriminately serves the public's bodily needs. Superficially devoid of all artistic connotations, since it is a receptacle for human waste, the urinal activates the potential presence of the male spectator through the pun arroser (to water or sprinkle), thus suggesting the punning coincidence of art and eros (arose ) in a gesture we least expect to associate it with: that of expenditure or waste. Like a lingering smell, the urinal bears the unassailable imprint, the impression of the spectator's body as a negative, and thereby mechanically "draws" in the spectator.

The invisible inscription of this olfactory dimension follows the logic of the infrathin: "smells more infrathin/ than colors" (Notes, 37). Duchamp invokes the olfactory sense in discussing modern art's loss of its "original perfume," its vulgarization when taught according to a "chemical formula": "I believe in the original perfume, but, as all perfume, it evaporates very quickly (after a couple of weeks, or a couple of years maximum); what is left is the dried kernel (noix sechée ) classified by the art historians in the chapter 'history of art.'"[23] Playing on painting as a medium that involves both color and smell (which adds an invisible dimension to painting, like traces of turpentine), Duchamp uses this analogy to comment on the fate of art that has lost its originality. Originality is described as evanescent, precariously inscribed in the work and fleeting like the smell of perfume. The work itself is only the "dry" imprint of a "wet" medium, and thus, ironically, classifiable as art only once it has ceased to exist as a process. This is why smells are more "infrathin" than colors, since the former invoke different sensations at the same time; even as it has ceased to be a liquid through evaporation, perfume lingers as a gas. This may also explain why Duchamp chose the urinal, that is, a mass-manufactured object which, like painting, bears the invisible traces of smell.

Had the viewer missed the olfactory dimension of Fountain as an instance of "dry" art, this allusion is spelled out explicitly in a later work, Beautiful Breath, Veil Water (fig. 49). This empty perfume bottle in a box

Fig. 49.

Marcel Duchamp, Beautiful Breath, Veil Water

(Belle Haleine, Eau DE Voilette), 1921. Assisted

ready-made: perfume bottle bearing label with

photograph of Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy,

height 6 in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Fig. 50.

Book cover designed by Duchamp. Walter Hopps,

Ülf Linde, Arturo Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp:

Readymades, etc., 1913–1964. Paris: Le Terrain

Vague, 1964.

Courtesy of The Menil Collection, Houston.

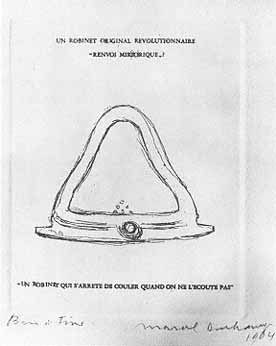

Fig. 51

.Marcel Duchamp, Mirrorical Return (Renvoi Miroirique),

1964. Copperplate engraving, 7 1/16 x 5 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Menil Collection, Houston.

is relabeled with a picture of Duchamp's alias and signature Rrose Sélavy. The work wittily refers back to Fountain literally in disguise, as veiled toilet water (eau de toilette ). Thus the potential inscription of liquid built reversibly in the urinal/fountain is repeated here by the empty perfume bottle, which invokes the absence of liquid by alluding to the perfume (as gas). The toilet water whose female associations are those of veiling or masking bodily odors becomes veiled water (eau de voilette ), a pun on Duchamp's abandonment of painting (as a "wet" medium). This empty bottle, bearing Duchamp's picture travestied as Rrose Sélavy, captures the fragrance of the artist as a seductive woman. Authorship is deessentialized, or rather, reengendered through reproduction. A "female" analogue of the "male" fountain, this work locates artistic originality within the ephemeral scent, the immanence of the "arrhe of painting is feminine in gender"(WMD, 24).

In order to further elucidate the nature of the artistic and gender inversions engendered by Fountain , it is important to consider the mechanism

of verbal and visual puns staged by this work. In 1964 Duchamp produces an ink copy of Stieglitz's photograph of Fountain, on the basis of which he designs a cover for an exhibition catalog, Marcel Duchamp: Ready-mades, etc., 1913–1964 (fig. 50). This cover, which looks like a photographic negative, is later reproduced in an etching that is its positive image, entitled Mirrorical Return (Renvoi miroirique; 1964) (fig. 51). The etching contains three inscriptions: the title "An original revolutionary faucet" (Un robinet original révolutionnaire ); the subtitle "Mirrorical return?" (Renvoi miroirique? ); and a motto, "A faucet which stops running when no one listens to it" (Un robinet qui s'arrête de couler quand on ne l'écoute pas ). Structured as an emblem, the visual and linguistic elements set up a punning interplay that helps us to explore further the mechanisms that Fountain actively stages. On the one hand, there is the mirror-effect of the drawing and the etching, which, although they are almost identical visually, involve an active switch from one artistic medium to the other. On the other hand, there is the internal mirrorical return of the image itself, since this urinal, like the one in 1917, has been rotated ninety degrees. This internal rotation disqualifies the object from its common use as a receptacle, and reactivates its poetic potential as a fountain; that is, as a machine for waterworks. The "splash" generated by Fountain is thus tied to its "mirrorical return," like the faucet in the title.

The predominance of the r 's in the text accompanying the image insinuate the implicit significance of the word art (arh) to the decoding of this image. In other words, the legibility of the image is activated by the pun on "r," [arrhe or art, in French), which, if not articulated, stops working, like the "faucet which stops running when no one listens to it." In other words, Fountain can only make artistic sense when the linguistic faucet is switched on. The word faucet (robinet ) means cock, valve, or tap, and turning the faucet means turning on the waterworks.[24] The punning associations of the faucet bring together all the elements that define Fountain as a Mirrorical Return. These include the "mirrorical return" of art and nonart; the "mirrorical" reproduction and switch from one artistic medium into another; and the notion of gender inscribed as a hinge, a pun that switches back and forth between the male and the female positions. It is not surprising that Duchamp's signature on Fountain, "R. Mutt," which translates literally as "Mongrel Art," is re-signed later (in a

1950 facsimile) by "Rrose Sélavy" (a pun on Eros c'est la vie or arroser la vie), his female alias. Rrose, an anagram of eros, is also a pun on arroser (to water, wet, or sprinkle), a play on the so-called "male" connotations of Fountain.

What initially appears as an instance of Duchamp's conception of "dry" art now emerges as a convincing example of "wet" art. The status of art in this work emerges according to the logic of the "mirrorical return," that is, as a potential mode rather than as an inherent quality.[25] In his notes on the "Infrathin," Duchamp explores the notion of modality:

mode: the active state and not the/ result—the active state giving/ no interest to the result—the result/ being different if the same/ active/ state is repeated. / mode: experiments.—the result not/ to be kept—not presenting any/ interest—(Notes, 26)

Considered as a faucet, the significance of Fountain may be found in its active state as an artistic, erotic, and punning machine. As suggested earlier, the interest of this work is not manifest in its result—its objective character—but rather in the differences produced through the impressions or imprints of the object's reproduction. Fountain is, therefore, an experiment rather than a product, whose interest is purely speculative, insofar as it explores and transforms the boundaries defining a work of art. As an art object, Fountain provisionally hovers at the limits of art and nonart; its existence is purely conditional. The referential meaning of art, as a copy of nature according to good taste, is here eroded through reproduction; a new concept of value emerges through circulation and consumption. The artistic value of Fountain in the age of mechanical reproduction is inseparable from this effort to conceive value in a dynamic, rather than static sense. The erosion of the concept of value as an inherent property of a work of art is transformed by examining the expenditure of value through its circulation and reproduction. The value of Fountain no longer refers to a traditional concept of art but instead to the conditions rendering inseparable the distinction between art and nonart. The "splash" of the Fountain/ urinal creates an active interval, making it impossible to affirm the uniqueness of art without considering the possibility that at any moment it might revert into nonart, like the faucet that

stops running when no one listens to it. As Duchamp explains to Schwarz: "What art is in reality is this missing link, not the links which exist. It's not what you see that is art, art is the gap."[26]