6—

Like-Minded Companions

The Master said: "If his substance exceeds his style, he's a rustic. If his style exceeds his substance, he's a pedant. But if his style and substance are in harmonious balance—why, then, you have the gentleman."

Analects 6.16

That the portraits of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi continued to have important social resonance in succeeding decades is attested by the recent discovery of two more examples of the same pictorial images (figs. 4–6). The remains from yet a third tomb, although yielding no pictorial evidence, suggest strongly that portraits of the same cultivated gentlemen comprised part of the tomb décor. I do not doubt that its basic components were identical to the three portraits now extant.

The pictorial evidence is the strongest evidence for the continued fame of the Seven Worthies and for the continued strength of one specific tradition about them.[1] However, the fact that the patrongroup for these later portraits differs from that for the Nanjing mural

raises intriguing questions. It is not unusual (anywhere in the world) for private patrons, men of lower rank, to emulate their social superiors. In this case study, however, we find the converse, for emperors have appropriated images made of lesser men for lesser men (in rank, that is). If our images were displayed in obeisance, paying homage to the ruler, their presence in the tombs would occasion no surprise. But that is not what we see. An inquiry into some of the important social changes of the fourth and fifth centuries suggests reasons for their presence in imperial tombs which reaffirm the rhetorical function of early Chinese portraiture.

Unlike the Nanjing portraits, these later portraits from Danyang county, the home of the emperors of the Southern Qi dynasty, are not the only pictorial images in the tombs. They are but one part of a pictorial system, a system remarkably similar in all three tombs and suggesting, therefore, deliberate selection and placement of motifs. Their association with other images yields further interpretations of the portraits, whereby the earlier meaning is not altered, but rather heightened. That is to say, like all successful pictorial conventions, those of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi were sufficiently flexible to allow for ready adaptation to changing circumstances and to acquire new layers of meaning. In their new setting, the symbol of the cultivated gentleman acquired an almost sacred character.

We cannot identify the recently excavated tombs in Danyang with specific Southern Qi emperors. Only one of the three is known with certainty to be the Xiu'anling, the tomb of Xiao Daosheng (d. 478).[2] He did not rule, but was elevated as the posthumous emperor Jing by his son, Xiao Luan (Ming Di), upon the accession of the latter in 494/495. The new tomb (to which presumably the remains of the posthumous emperor were removed) must therefore have been constructed sometime between 495 and the date of Emperor Ming's death, 498.

The other two tombs were tentatively identified in the original archaeological report as belonging to the penultimate ruler, Xiao Baojuan (posthumously marquis of Donghun), who ruled briefly from 499 to 501, when he was deposed, and the last emperor, who ruled even more briefly until 502, Emperor He (Xiao Baorong).[3] Sometime later the original excavators concluded that the tomb first associated with the marquis of Donghun might equally well have been the final resting place for Xiao Changmao (known also as Wenhui), crown prince and heir apparent to the second Qi emperor, Wu (r. 482–493).[4]

The heir apparent, alas, preceded his father in death by some few months. Upon inheriting the throne in 494, Wu Di's grandson, Zhaoye, elevated his father as the posthumous emperor Wen.

Regardless of specific identifications, all three tombs were probably constructed sometime between 493 and 502, within a space, that is, of some nine years. The tomb remains, moreover, make it clear that the pictorial programs of all three were nearly identical. The inclusion of portraits of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi in these tombs has therefore less to do with idiosyncratic choice than with convention. The specific identities of the tomb occupants are, in this sense, irrelevant to the present discussion.[5] Portraits of exemplars—men who were seen as cultivated gentlemen—were, I suggest, normative for imperial tombs of the dynasty.

Nor can the duplication of pictorial décor be argued on grounds of economy (although the two tombs for which we have pictorial remains show indubitable signs of hasty or coarse construction).[6] Although the pictorial programs of the tombs were similar, the individual forms within each tomb differ in their details. New molds must have been carved for the brick reliefs of each tomb. The two Southern Qi portraits of the Seven Worthies were not made from the same molds, and neither was made from the molds that were used to produce the earliest relief.[7] The subject of the Nanjing relief may well have been chosen on the basis of personal inclination. The choice of the Danyang reliefs, I submit, was tied to a social ideal, for the depiction of which certain images had previously been created and continued to be readily available. The imperial tomb portraits are real and therefore the firmest evidence of their importance to the royal family; the argument for their selection, unfortunately, must be circumstantial. It is reasonable to assume that those who commissioned the tombs, presumably members of the immediate families, would have approached the choice of pictorial décor with two questions in mind: How did it relate—factually or ideally—to the deceased, and what would those who attended the funeral think of it?

Shaping Thoughts

Life for most inhabitants south of the river changed but little after the end of Eastern Jin. Dynasties rose and fell; indigenous tribal groups constantly required pacification; skirmishes and battles with the

invaders who had conquered the north kept the borders fluid. By the fifth century the Toba had unified the north to rule as the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535), which alternately warred and traded with the southerners. In the south, as the nobles, powerful officials, and imperial favorites arrogated more lands and tenants unto themselves, the poor got poorer and the rich got richer.[8] Nevertheless, for the privileged few there were changes.

In the fifth and sixth centuries the oligarchical rule of the Great Families gave way to imperial dominance. In the Eastern Jin period, competing families had managed to dominate puppet emperors. In succeeding periods, a few strong emperors managed to dominate competing families and alter the balance of power. In the Liu-Song dynasty, for example, Emperor Wen (r. 424–454) astutely wrested control from the powerful families who had placed him on the throne. Even the Xie family, under the new state of affairs, was to be curbed. Xie Lingyun, for instance, was the duke of Kangle. Wealthy, talented, and most certainly untrammeled, he failed to stoop with the times. Diverting public streams and lands to his own use, he fell afoul of appointed officials.[9] Further arrogant behavior angered the throne, and he paid with his life. Years later, during the Southern Qi dynasty, his grandson would pay the same price.[10]

The Great Families, of course, retained their wealth and social status. From the time of the Song dynasty through the Chen, however, as successive emperors relied increasingly on the support of men of lower status (the hanmen ) and members of their own families, the political power of the Great Families, qua families, waned. Hanmen themselves, the new rulers rose to power through military prowess. Making no effort to deprive higher-ranking families of their privileges, including their right to hold certain offices, they managed nevertheless to alter the balance of power by narrowing these virtually hereditary offices to functions largely ceremonial in nature. Simultaneously, they appointed other hanmen, who had largely demonstrated their talents on the battlefield, to civil offices which, although often of low rank, nevertheless afforded real power.[11]

Such a one, for example, was Xiao Daocheng (427–482). A northern family, the Xiao had crossed the river during the upheavals at the end of the third century to settle in Southern Lanling. The family claimed descent from a minister of the Western Han period, down through twenty-four generations of officials. Nevertheless, we first hear of them in the Song period, when Xiao Daocheng rose to prominence through military exploit, to become a general and the duke of

Qi.[12] As weaker emperors succeeded Song Wen Di, the mighty general became the protector and power behind the throne. In the end, he bowed to the importunities of loyal ministers and in 479 mounted the throne in his own right, as Emperor Gao of the Southern Qi dynasty.

The new dynasty, wracked by incessant struggles for the succession among Daocheng's direct and collateral descendants, was bloody and short-lived.[13] In 502 a distant relative—and yet another general—deposed the last Southern Qi emperor, to establish himself as the first emperor of the Liang dynasty (502–557).

As their real power faded, it is little wonder that the Great Families (and, indeed, all members of the official class) became ever more zealous in insisting on their legal status as high-ranking, "pure" families of the realm. The perquisites accompanying such status were real enough, and the offices they were entitled to hold could, if properly filled, ensure continued wealth.[14] Since a family's lineage and the high offices filled by ancestors were determining factors in a family's status and privileges, genealogies loomed large in discussions of the period, and the official registers that formed the basis for determining family status became a constant source of contention.[15] Southern families were not supposed to have the same privileges as northern émigré families; more recent émigrés from the north were looked down upon by everybody; hanmen were not to hold high office; the "pure" and the "muddy" should never mix. Or so it was argued.

In fact, they did mix. The obsession tells us so. The vehemence of Shen Yue's famous accusation against a member of the official class who married his daughter to a man of dubious ancestry argues that it was no isolated incident.[16] "If this tendency is not cut short," he exhorted the emperor, "the flood gates will open, and the dirtying of generations and the begriming of families will spread everywhere."[17] Shen Yue deplored the decay of manners and morals as families of the official class (yiguan ) disregarded their proper station. "Their relatives by marriage are of the lowest sort; . . . clear-eyed and shamelessly, completely without reverence, they put their ancestors up for sale, as if they were roadside peddlers."[18]

On paper, it was a rigid class system; in life, a more mobile society prevailed in which a low-born man of talent and a high-born family with daughters could join forces to do well.[19] Several daughters of the Langya Wang clan, for example, became empresses in the Southern Qi period, and Langya Wang and Xie males married princesses of the Song and Xiao imperial lineages, to the benefit of both sides.

Casting and Cutting

Beset both by external forces from the north and by internal contention, and therefore occupied with the incessant struggle to maintain power, the governing elite, it might be assumed, could have had little time or thought for the niceties of life. On the contrary, the arts flourished, to such an extent that the Toba-Wei rulers of the north were dazzled by southern culture and refinement, by reports of the splendid palaces and Buddhist temples that adorned Jiankang, and sought to emulate their enemies.[20] The southern emperors chose eminent scholars as tutors for their sons and sponsored academies of learning for children of high-ranking officials.[21] When the Qi crown prince Changmao (Wenhui) resided in the Eastern Palace, for example, one of his staff members was Shen Yue (441–513). Courtier, historian, bibliophile, phonologist, poet, and essayist, Shen Yue rose from poverty to serve three dynasties.[22] His influence on the heir apparent was so great that no king or noble seeking favor obtained it without his approval.

An educated man was expected to know the traditional Confucian Classics, the works of Laozi and Zhuangzi, and history.[23] Changmao himself lectured and debated at the National Academy on the Rites, the Yijing, and the Classic of Filial Piety.

Above all, an educated man was expected to be interested in literature—to create it, if he could, and to have ideas about its creation. The late fifth and early sixth centuries became another bench mark in the history of Chinese literature, when for the first time literature was officially separated from scriptural scholarship, philosophy, and history.[24] It was a fulfillment of Cao Pi's third-century tentative valuations of literature as an endeavor to be appreciated, and rewarded, in its own right.

If the most creative names associated with that literature came more often from families of the shi or official class, the greatest patrons were members of the imperial families.[25] Surrounding themselves with men of literary talent, they created private salons for which the sole criterion for membership was devotion to literature and learning, rather than official rank or family status. Needless to say, only men of considerable education were qualified to participate in these activities, as they amassed libraries, assembled anthologies, and critically scrutinized the literature of the past.[26] Although this education was devoted, in these circumstances, to private (or at least semiprivate) activity, it was not without political and social consequence. Men

of literary talent, for example, found patrons among members of the imperial family. Dependent upon their specific patron, their political and social fortunes were, like those of erudites of the early third century, allied to his. It required considerable skill for a littérateur to stay in favor with his patron yet retain sufficient independence to leap from a sinking ship and survive. Moreover, the men of a particular literary coterie, although of varying official ranks, nevertheless interacted as equal participants who admired, supported, and recommended each other.[27] Thus, literature—its study and expression—became an avenue to official promotion and social mobility.

Changmao's brother, Xiao Ziliang, King Wenxuan of Jingling (460–494), presided over such a group at the famous Western Lodge, outside Jiankang.[28] An antiquarian like his brother, Ziliang was a collector and a connoisseur.[29] The prince's biography states that he summoned scholars to copy the Classics and other works, and Buddhist monks to debate the Law and regulate the chanting of sutras[*] . "Not since the crossing of the River [in 317] had clergy and laity so flourished."[30]

The group of scholars summoned to the Western Lodge was the forerunner of the more famous, and self-conscious, literary salons of the succeeding dynasty. Although the prince's biography does not name any of the men who gathered around him, later sources are more specific. Shen Yue's biography in the Liang shu mentions six: Ren Fang, Fan Yun, Wang Rong, Xie Tiao, Xiao Chen, and, of course, Shen Yue himself.[31] The Annals section of the same history, however, adds two more names: Lu Chui and Xiao Yan, who later became the first Liang emperor.[32] They were called, say the Tang historians, perhaps in reminiscence of the Prince of Huainan's circle of friends (second century B.C. ), "the Eight Friends." Men both from southern and from northern families and of varying social backgrounds thus came together to pursue their common interest, literature.[33] And if the king of Jingling is not remembered for his own literary talent, he is famous as the patron of some of the most eminent poets and scholars of his day, men who inaugurated the great Yongming efflorescence of literary activity.

Fame

The tradition of the Seven Worthies intersects with the literary interests of the period to form new angles from which we may view

their continuing importance as symbols of the cultivated gentleman. If we knew only that the New Tales of the World continued to circulate widely in these later centuries, that fact would be sufficient to establish the continued interest in our subjects. That Liu Jun, probably about the end of the fifth century, produced a commentary to the earlier work suggests that the original had not lost its appeal. It is to this commentary, as I have earlier noted, that we owe our knowledge of many other anecdotes about the Seven Worthies, and we are thus assured that they were in circulation at the end of the century.[34]

Perhaps the most important evidence for the continuing tradition of the Seven Worthies as cultivated gentlemen is to be found in Huijiao's Lives of Eminent Monks (Gao seng zhuan ), completed sometime between 519 and 530.[35] In his pious contribution to hagiography, Huijiao included Sun Chuo's fourth-century characterizations of early Buddhist monks, each spiritually one with the Worthies of the Bamboo Grove. If the Worthies' images as cultivated gentlemen, lofty and tranquil, had not continued to be potent, Huijiao would not have made a point of including them in his proselytizing work.[36]

From these two sources alone we would be certain that the cultivated gentleman, as exemplified by the Seven Worthies, was still an important social ideal. But that ideal had become more complex in real life, and it is therefore of value to inquire into the tradition more closely, for it must be seen to affect the actions or interests of rulers.

Shen Yue, who himself was likened to Shan Tao for his circumspection and length of service, wrote an essay on the Seven Worthies.[37] Xi Kang and Ruan Ji, men of outstanding talent, lived in a corrupt age and were the victims of vile slander, he said. Beset by danger, theirs was a rugged road. Their rejection of ceremony and proper behavior, their carousing, were merely devices, a cover, to protect themselves. "So they filled their cups the whole day through." One cannot drink alone, he notes, and so the other five were invited to join the group. "Together, with no discord, arm in arm, under the great trees they rambled. . . . From [this] distance, we relish the wonderful [stories], but their profundity we can barely discern."[38]

Like earlier poets, such as Tao Yuanming and Yan Yanzhi, the Qi and Liang poets imitated the works of Ruan Ji and Xi Kang, and in abundance. Every nuance of such imitations, or of allusion, would have been readily grasped by the audience for whom they were written.[39]

With the explosion of interest in literature, some of our exemplars received a good deal more attention than did others. The literary savants of the time were far more interested in the works of Xi Kang

and Ruan Ji than they were in the political successes of Wang Rong or Shan Tao. The Wen xuan, the great literary anthology compiled under the direction of the crown prince of the Liang dynasty, Xiao Tong (501–531), includes many works by Xi Kang and Ruan Ji, one work by Xiang Xiu (his reminiscence of Xi Kang), and Liu Ling's "Ode to Wine."[40] Zhong Rong (469–518), in his Shipin (Criticism of Poetry), assigns both Xi Kang and Ruan Ji to the upper ranks of poets.[41] Ruan Ji's work, he remarks, "abounds in melancholy," while Xi Kang's poetic figures are "pure and remote (qing yuan )."[42]

Finally, I turn for guidance to that supreme contribution to Chinese literary theory and criticism, Liu Xie's The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons (Wenxin diaolong ).[43] Discussing literary talents of the past, Liu Xie remarks that Xi Kang's essays express "the mind of a master" and that Ruan Ji's poetry "is permeated with his whole spirit and life." Evaluating poetry of the Zhengshi period (240–248), Liu concludes that only Xi Kang, "whose works are characterized by pure and lofty [qing jun ] emotions, and Juan [Ruan Ji], whose ideas are far-reaching and profound, achieved outstanding stature."[44]

Ruan Ji "sang in the spirit of a recluse a tune wafted into the distance," while Xi Kang "gave us high spirit and bright colors." In his discussion of musical poetry (yuefu, literally, Music Repository), Liu Xie refers once to Ruan Xian, whom he commends for his musical acumen.[45] Thus, many of the same qualities that men of the fourth century applied to the personal characters ofXi Kang, Ruan Xian, and Ruan Ji were seen by men of the late fifth and the sixth century to characterize their literary gifts.[46] They were judged and ranked as artists (or, like Ruan Xian, as connoisseurs) in precisely the same terms with which they might once have been recommended for office or, as we have seen, as social examplars. The art of judging had discovered Art.

Liu Xie's high opinion of Ruan Ji and Xi Kang did not extend to all the members of the Bamboo Grove, however. Xiang Xiu's deficiencies as a writer, for example, were revealed by his exaggeration of Xi Kang's political errors; it was a literary, as distinct from a character, flaw (although, as we shall note, the two were not without connection). As for Wang Rong, we are told only that he "vulgarly sold offices and haggled for bargains."[47]

It is only natural that those Worthies who did not write essays and poems should, as a result, receive scant attention from Liu Xie and his literary-minded contemporaries. Yet in his remarks about Wang Rong one detects a certain disdain, a hint of a judgment that, all in all,

artists are superior to men of action, whom worldly pursuit inevitably sullies. Of course, literary writers also have their faults of character, and Liu Xie's list is lengthy and heterogeneous. Some writers, alas, were greedy, corrupt, or frivolous. Others loved to drink, had no sense of shame, or were haughty and conceited. Although these latter charges, as we know, were often leveled at the Seven Worthies in the past, none of their names appear on Liu's list, one which he promptly balances by pointing out that generals and ministers also have their flaws. If a man of Wang Rong's caliber had faults, asks Liu Xie, why expect otherwise of writers? In spite of his shortcomings, however, Wang Rong was not excluded from the Bamboo Grove, because he had achieved a great name, "and the criticisms [against him] were somewhat moderated."[48]

Aside from the historical fact that Wang Rong's illustrious career (and peccadillos) was realized long after the purported date of the revels in the Bamboo Grove, several points are raised by Liu Xie's remarks. The first is that the sixth-century critic sees the Bamboo Grove as something of value, a circle for the elect. Moreover, since Ruan Ji and Xi Kang are consistently praised by Liu Xie as writers, and since other Worthies are either not mentioned at all (Shan Tao, Liu Ling) or mentioned only in passing (Xiang Xiu, Ruan Xian), it is reasonable to assume that Liu Xie perceived the two poets as the leaders of the group, who chose to admit Wang Rong (who had faults, as they did not). Finally, it appears that Liu Xie regards those who produce literature as more valuable than, for example, those who are merely chief ministers of the land. His views of the Bamboo Grove are not so different from those of Shen Yue, who also distinguished among the members of the group. Ruan Ji and Xi Kang were men of sincerity, forced to hide their deepest feelings; the others joined them in the Grove simply because they were convivial.[49] Shen Yue speaks of the men, Liu Xie of their literary works; in either case, the emphasis is on the same values of profundity, purity, loftiness. Dai Kui's earlier defense of the men of the Bamboo Grove seems now, in Shen Yue's version, tinged with rue, like Tao Yuanming's perception of Rong Qiqi. Prices must be paid, compromises take their toll, as Shen Yue well knew.[50]

The valuation of men of literary attainment as superior to government ministers appears to reverse that of the men discussed in the preceding chapter, men who weighed almost every talent and action in terms of ability to hold office, and it is therefore instructive to inquire further into Liu Xie's point of view.

In drawing on his formulations, I do not mean to imply that he created the image of the gentleman for his period. For the argument at hand, the significance of his work resides in its reflection of certain values and concerns of his period. Our concern is with royal exemplars, and we shall observe that this image shines most brilliantly in his text. To whom, we must ask, did Liu Xie address his words, those exquisitely balanced phrases, so recondite that only men of superior perception could have appreciated them? (We are told, for example, that Shen Yue kept a copy of the work in reach at all times.)[51]

The Capacity of a Vessel

Liu Xie tells his readers that "he who wants to stand out above the others must depend on his intelligence. . . . If a man really wants to achieve fame, his only chance is to devote himself to literature." He has thus moved beyond Cao Pi's earlier view that literature is one of two ways to achieve fame and immortality. It has become the only way. This narrows the field considerably, for, as Liu Xie repeatedly stresses, literary talent is innate. It cannot be acquired. "In the use of language and in the grasp of content, a man is destined to be either mediocre or brilliant, and no one can make him what is contrary to his talent." Yet, this innate talent, if it is to result in good writing, must be cultivated. "And no one has ever heard of achievement out of proportion to a man's scholarship; and in style and form, he is destined to be either graceful or vulgar, and few can be what is contrary to their training." Liu Xie's view of human nature is, in fact, no different from that of Liu Shao in the third century, nor has the realm of discourse changed so entirely as it would seem. For "the beauty one imparts to his language depends . . . entirely on his temperament and nature."[52] Ruan Ji, therefore, sang in the spirit of a recluse because he was "easy and free [ti tang ]." Xi Kang gave us high spirit because he was "outstandingly talented and gallant [jun xia ]."[53]

Elsewhere Liu Xie insists that the main purpose of literary writing is not to achieve fame but to express the inner feeling.[54] Although the ancient poets understood that purpose,

works which are based on genuine feeling become more scarce every day, while those that aim at merely literary achievement become more and more abundant. People whose minds are completely dominated by worldly ambition sing vaguely of retirement, while people whose hearts are wholly entangled in the business of the day purposelessly paint a

life beyond this workaday world. These people have lost their souls, and live lives of contradiction.[55]

We need not be concerned with those at whom Liu Xie may have aimed his barbs. What matters is that this only road to fame requires, in addition to talent and scholarship, sincerity. A man's writing, to be great literature, must truly correspond to his inner being. Those who are dominated by worldly ambition do not create Art.

There was once a (Golden Age for men of literature, Liu Xie tells us. Cao Cao and his sons, Cao Pi and Cao Zhi, themselves loved and wrote poetry. "These three, important as their positions were, all showed great respect for others who had outstanding literary talent. Hence, many talented writers gathered around them."[56] It was a glorious time, as

goblets in hand, [they] proudly showed their elegant style and, moving with a leisurely grace while they feasted, formed songs with a swing of the brush. . . . An examination of their writings reveals that most of them are full of feeling. This is because they moved in a world marked by disorder and separation, and at a time when morals declined and the people were complaining, they felt all this deeply in their hearts, and this feeling was expressed in a style which is moving. For this reason their works are full of feeling and life.[57]

Thus do great images survive.[58] As for Liu Xie's own era (the Southern Qi), his panegyric to the dynasty suggests that once again a Golden Age may have descended: "When our august Ch'i [Qi] came to rule, all good fortune descended upon the virtuous and enlightened. [All the previous Qi rulers] were gifted with literary talent and all were men of enlightenment; continuously brilliant, they have enjoyed great blessings."[59] See how the present ruler's talent and patronage glorify the realm:

Now His Majesty has just begun his sage reign, and the world is bathed in the light of his literary thought. The deities of the seas and mountains bestow upon him divine perception, causing his native talent to flower forth. He drives the flying dragons through the heavenly path, and harnesses the thoroughbreds for a ten-thousand-li trip. Works on the Classics and government institutions under his reign have surpassed those of the Chou [Zhou] and can look down upon those of the Han with contempt. . . . Such great style and wondrous beauty I with my sluggish brush hardly dare try to depict.[60]

Liu Xie is unambiguous—its literature makes a dynasty great. Moreover, as he cautions elsewhere, only experts are qualified to appraise that literature. It is therefore essential, he argues in his final

chapter, that literary men be employed in government, for only they combine the ability to manage affairs of state with the "beautiful patterns" in which that ability must properly be expressed. Neither pedigree nor wealth will glorify the dynasty, and he who would be a great ruler must recognize where true greatness lies, cultivate it in himself (if he is fortunate enough to have the talent), and seek it in others.[61]

When official rank and unofficial power diverge, new standards are likely to be raised in pursuit of privilege. As the actual power of the Great Families waned, and as men of lower family-rank supplanted them, the criterion of "talent" was once again promulgated as the measure. This time, however, the sign of talent (as Liu Xie argued the case) was literary knowledge and ability. It automatically ruled out anyone, high or low, who could not write, or who failed to appreciate such writing, which is to say, those who lacked either literary talent or education or both.[62] And it offered the descendants of even military men another way to become cultivated gentlemen—a way that might even exclude some of their higher-born in-laws.

The true gentleman of the fourth century was recognized by his tranquillity and cultivated self-possession. Perhaps no single idea is alluded to more frequently in Qi and Liang discussions of literature than the quotation from the Analects that heads this chapter: "If his substance exceeds his style, he's a rustic. If his style exceeds his substance, he's a pedant. But if his style and substance are in harmonious balance—why, then, you have the gentleman (junzi )." Now, however, the dictum of Confucius is applied, not to men, but to their literature, the substance and style of which must be in harmony. This balance in literature, however, occurs only when that literature is in harmony with the character of the writer. It is a basic theme of Liu Xie's aesthetic, one to which he repeatedly alludes.[63]

The emphasis on the words of the Master was not, as it might seem, a plea for a return to Han propriety and decorum. The direct source for Liu Shao's standard was not the Confucian Classics. It was Cao Pi. His ideas on literature were the springboard for the important literary criticism of the Qi-Liang period, including Liu Xie's brilliant treatise. In the letter mourning the loss of his literary friends, the future Wei emperor had subjected their work to critical scrutiny and had referred to the same ideal, in the context of literature. Xu Gan, he said, "harbored his inner being (zhi ) in his literature (wen ). Calm and with few desires, he yearned to retire to Ji Mountain. We may say that [in his] harmonious balance he was truly the gentleman."[64]

Liu Xie's allusions to an allusion, therefore, were not a rejection of Wei-Jin thought and behavior, but rather a recasting—almost an elevation—that upheld new standards of decorum. Behavior (literary style, wen ), as always, marked the man (his talent, his character, substance, zhi ). Only when the two appeared in harmonious balance could one find, not only great literature, but the junzi. The cultivated gentleman had become a classic.

Vita Breva, Ars Longa

As in literature, so in life. Ministers and rulers, poets and ideal readers complement each other. "The writer's first experience is his inner feeling, which he then seeks to express in words. But the reader, on the other hand, experiences the words first, and then works himself into the feeling of the author. If he can trace the waves back to their source, there will be nothing, however dark and hidden, that will not be revealed to him. "[65] As Shen Yue understood the true feelings of Xi Kang and Ruan Ji (and the profound significance of the Bamboo Grove), as Liu Xie discerned the true quality of literature, so the ruler, in this paradigm, understood the true worth of his subjects.

Was the ruler listening to Liu Xie's argument? We know from the history of the period that princes of the Qi dynasty surrounded themselves with literary men, that they embellished the capital with fine palaces, splendid gardens, great temples. They sent as emissaries to the northern court only the most refined and cultivated of diplomats, able, presumably, to drive hard bargains, but able also to impress with their wit and refinement.[66] They were, in short, patrons of the arts and of gentlemen. Moreover, the southern emperors were exemplars, in terms of all things cultural, to their northern counterparts.[67] Liu Xie drew for his argument on real events and transformed them into a literary image in which any ruler, or aspiring ruler, could see himself mirrored.

As for a corresponding pictorial image, it did not require invention.[68] It was already there, rich in suggestion, simple to reproduce. Refined and self-possessed, pure and tranquil, the images of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi retained their earlier "character" but gained in depth. They too had become classics, models in their talent and ability for both rulers and courtiers, reminders in their life trajectories for those courtiers who wished to keep their heads (in

truth, they needed no reminders). And do they not also, in their group of eight, form a harmonious balance—from the total rejection of the world by Rong Qiqi to the complete immersion in worldly affairs of Wang Rong? As a group, in a sense, they sum up the totality of the courtier's world, and the courtier's dilemma. From the point of view of a ruling family, especially one of somewhat murky origin, is it not the mark of the true gentleman to appear in the company of such famous and gifted men, to join with them—like Cao Pi, primus inter pares, unceremonious but refined—in the subtlety of their outings, "like-minded persons to whom one is committed in friendship?"[69] The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove, as idea and its pictorial translation, are at once a link to the past and a timeless evocation of noble behavior and profound feelings. The tomb reliefs are the evidence that the imperial family had arrogated the symbol of the cultivated gentleman unto itself.

The influence of images, literary or visual, cannot be overestimated. One small anecdote in the History of the Qi Dynasty exemplifies their potency. The son of a general, Zhang Xintai, whose true bent was for calligraphy and history, had no choice (because of family classification) but to follow a military calling. A misfit, our hero dressed himself in patched clothing and deerskin cap, carried a zither, and rambled the countryside with common folk. The emperor was shocked by reports of his behavior, so unbecoming to the son of a general, and later ordered an inspection of his armor and weapons. The equipment thus confiscated, Zhang found himself with nothing to do. Settling beneath a pine tree in the imperial park, he proceeded to drink wine and chant poems.[70] Someone reported it to the emperor, who, in his rage, dismissed the hapless fellow. A few days later, however, in a calmer mood, the ruler summoned him and announced, "Since you don't enjoy being a soldier, we'll purify you (qing shi ) by giving you a civilian post."[71] This gracious bestowal by one capable of appreciating his true nature enabled Zhang Xintai to realize his natural métier. Ars est celare artem.[72]

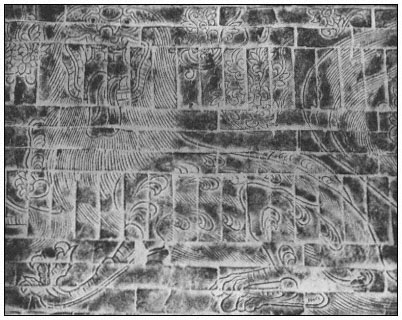

36.

Crow in the Sun.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Jinjiacun,

Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D.

Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

37.

Hare in the Moon.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Jinjiacun,

Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D.

Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

Immortality

For further interpretation of the portraits, I turn now to a description of the pictorial décor of the three tombs built in the Southern Qi period. All the tombs were early broken into; this and ensuing damage from the elements left no tomb wholly intact. Initial reconstructions of décor were based on each tomb's surviving pictorial and inscribed bricks, which were then compared with the remains from the other two tombs.[73] What follows is a composite description of the three.

Although they differ somewhat in shape, all are single-chamber, barrel-vaulted tombs fronted by a narrow passageway. Except for basalt doors and frames, all are constructed of gray bricks, with the bricks of the surrounding walls arranged in layers, the typical three rows of horizontal bricks to one row of vertical bricks.

Pictorial decoration comprised both wall-paintings and pictures in brick-relief. The former, found in the passageways, appear to have been painted in red, white, and blue on a green ground. Unfortunately, the colors had for the most part peeled off or faded by the time of excavation, and only faint daubs were visible.

Relief bricks, however, enable us to tell more of the original ensemble. Many of the bricks in the burial chamber are embossed with designs such as blossoms, coins, or relief lines in checkerboard patterns, some of which bear traces of paint.[74] All the relief murals are constructed of two or more molded bricks. In the corridor, above the first pair of stone doors, are two discs, identified by inscription as "Little Sun" and "Little Moon" (presumably referring to the size of the mural). A three-footed crow with wings outspread stands inside the sun (fig. 36). In the moon can be seen a tree, identified in the report as a cassia, under which a hare stands on his two hind feet, his front paws holding a long pestle that rests inside a mortar (fig. 37).

On either wall of the corridor sits a single lion (77 × 113 cm) with lolling tongue and upswept tail (fig. 38). Traces of red paint remain on ears, eyes, nose, and tongue; cheeks are flecked with white. Showers of blossoms fall around him. Between the first and second doors of the corridor, on each wall, stands a guardian warrior (79 × 31 cm), wearing pleated trousers and a mailed doublet. He clasps a long sword that reaches from his waist to his feet.

As one enters the main chamber, a long mural (app. 2.40 × 0.94 m) is seen on each of the upper long walls (figs. 39 and 40).[75] The picture on the left (west) wall shows a man rushing forward. Turning from the waist, he gestures to a long tiger striding behind him. The picture

38.

Lion.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Jinjiacun, Danyang county,

Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

(Photograph courtesy of James and Nicholas Cahill.)

on the right wall is similar: the animal, however, is a dragon. Inscribed bricks identify the images as "Great Dragon" (da long ) and "Great Tiger" (da hu ). The tall, slender men wear short tunics tied at the waist by ribbons that float behind them, while feathers sprout from their sleeves and tight trousers (figs. 41 and 42). They wave toward the animals fly whisks or sheaves of grasses. One holds out to his animal companion a small ladle from which flames emerge.[76] Cloudlike swirls that surround the images and accompany blossoms hanging in the air reinforce the sense of rapid motion conveyed by the prancing figures and floating garments.

Above each animal three small figures face the winged men (figs. 43–45). Their knees are bent, their long robes and scarves twist, ripple, and float behind them.[77] They, too, are accompanied by cloudlike swirls and floating blossoms. Each flying creature holds an object: a flaming tripod, musical instruments, a tray, clusters of what are,

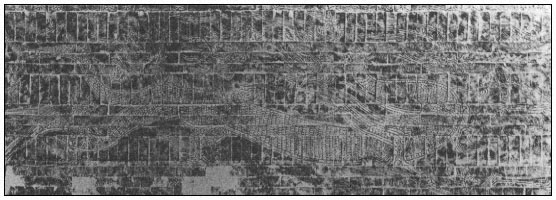

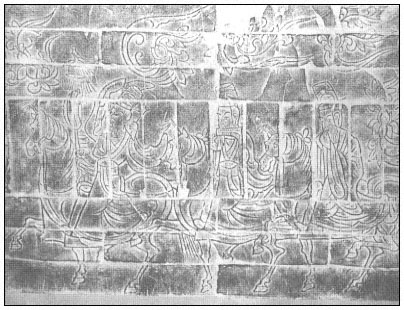

39.

Immortals with Dragon.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Wujiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province.

Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

perhaps, jewels or fruits. Inscribed bricks found in the tombs identify them as celestials (tianren ).[78]

The portrait reliefs of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi, each figure separated by a single tree and accompanied by an inscribed brick, follow the murals of winged men and striding animals, and at the same level. Two of the images are now missing from the Wujia tomb; the order of the remaining forms and their division on the left and right walls are identical to those of the Jinjia tomb, as they are to the earlier, Nanjing relief. They are, moreover, almost the same size as the latter.[79] Traces of red paint remain on trees and musical instruments.

A few centimeters below these images, series of relief pictures, separated by bricks with floral designs, combine to form uniform murals, some 4.97 meters long, on both walls. Together the figures form a procession of foot soldiers and cavalry. The mailed horses are festooned with pennants and feathers; robed or trousered attendants bear standards or canopies; mounted musicians tootle pipes and bang drums. These are the honor guard, fit for an emperor (fig. 46).[80]

Thus, the Seven Worthies portraits, the only figure reliefs in the Nanjing tomb, have a new status. From the stone mythical animals that once lined the outer paths to the tombs, to the relief lions and

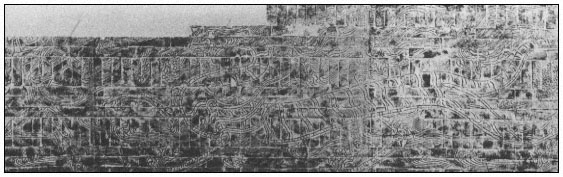

40.

Immortals with Tiger.

Rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at Wujiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province.

Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

warriors that guard the corridors, to the appanages of attendants, cavalry, musicians, and so forth, the Worthies are now associated with royalty, wealth, and power.[81] The basis for their association lies not in their once-worldly rank, but in their symbolic status—like-minded persons to whom one is committed in friendship.

The other images in the tombs bespeak the concern for immortality, for which the tomb was, appropriately, the traditional site for its pictorial expression. None of these images is new. Countless tombs from the Han dynasty display moon-rabbits pounding the elixir of immortality, for example, or immortals (xian ), feathered creatures sporting with animals.[82] The authors of the archaeological reports identify the latter scenes as "Ascending to Heaven," speak matter-offactly of "herbs of immortality" (the sheaves of grasses, the clusters held by one of the celestials), and suggest that the flames of ladles and tripods might be melting cinnabar (important for compounding elixirs of immortality).[83]

Neither chimney sweeps nor emperors wish to come to dust, and it is only reasonable that imperial-tomb décor should reflect earnest hopes as well as the right of the deceased to preferment. For did not Shen Yue, in his History of the Song Dynasty, note that the three-footed crow appears when the one who rules shows compassion and filial devotion?[84] And did he not explain that when the ruler refrains from

41.

Immortal with Tiger.

Detail of a brick relief mural from the Xiu'anling, Danyang county, Jiangsu province.

Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

(Photograph courtesy ofJames and Nicholas Cahill.)

delegating power to false ministers, the sun and the moon shine their lights brightly?[85]

The beliefs and their pictorial expressions are traditional. The association of scenes of immortality with portraits of the Seven Worthies, however, is new. The latter, like the images of the imperial cortège, represent the terrestrial existence of the deceased (his like-minded

companions), as the immortality scenes reflect his hoped-for heavenly existence. As such, the Seven Worthies murals, for reasons now clear, replace the countless images of bowing officials and imperial emissaries who attested the worldly fame and virtue of the deceased in Han tombs—a simple but sophisticated substitution.

Their pictorial association with such imagery may well imply that the Seven Worthies had themselves achieved immortality. From our point of view, this seems only appropriate. To this day they occupy a prominent position in Far Eastern thought and art; metaphorically speaking, they are immortal. For the men of the fifth and sixth centuries, however, immortality was no metaphor, and a great deal of energy was expended on achieving the desired reality.[86] Admiring the Seven Worthies, identifying with them, or emulating them in literary production or life-style, was one thing. Ascribing to them a realized immortality was quite another and, it seems to me, an innovation. Granted that the pictorial systems of these tombs utilize conventional images, the patron's choices from the pool available to him must nevertheless bear significance, if only in the superficial sense that he finds the images pleasing rather than strange or shocking.

The question I pose, then, is why did imperial patrons find it pleasing to see the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi, cultivated gentlemen and like-minded companions, in the company of immortals? The answer, I would speculate, lies in a fortunate accommodation of the Seven Worthies' ideal to the Daoist interests and beliefs of the Xiao family.

Six Dynasty developments in Daoist conviction and practice were to transform instituionalized Daoism forever.[87]A New Account of Tales of the World, so important an expression of values of certain of the fourth-century elite, makes no reference to the important instructions revealed by Perfected Immortals from the Heaven of Supreme Purity in a series of visions to an otherwise unknown Yang Xi. Nor does it mention their transcription—events that occurred at about the very time that Xie An, Sun Chuo, and Wang Xizhi were roaming the hills in convivial reclusion, debating Mysterious Learning, and admiring the landscape. Yet by the time of the accession of the first Southern Qi emperor, the esoteric texts of what was to become the Mao Shan sect loomed large in imperial interests. New realms of immortality, far higher and grander than those of the mere xian, had been revealed to Yang Xi, and it was not long before those who possessed its secrets attracted a following among the elite.[88]

There was no place in Mao Shan belief for the wonder-working

42.

Immortal with Dragon.

Details of figure 39. (From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

43.

Celestials with Tiger.

Detail, rubbing of a brick relief mural from the Xiu'anling, Danyang county,

Jiangsu province. Late fifth century A.D. Nanjing Museum.

(Photograph courtesy of James and Nicholas Cahill.)

fangshi, or diviners, on whom earlier rulers—Cao Cao, for example—had relied, or for the superstitions of common folk.[89] For the Mao Shan sect, the highest levels of immortality, the Ranks of the Perfected, were reserved for the elect, sensitive and refined folk, capable of grasping spiritual subtleties.[90]

As Daoist beliefs changed, so did the style of its pictorial imagery, as both adapted to the values of the aristocracy. Missing from the Danyang scenes are the stocky or brutish immortals of so many Han depictions, replaced by slender, elegant creatures, whose graceful gestures authoritatively lure dragons and tigers, and by celestials, so light they soar. Their scarves and ribbons fly and twist in the wind, but they lose none of their unruffled composure. "How light and airy his graceful soaring," Zhi Dun had once remarked of Wang Meng.

44.

Celestial.

Detail of figure 39.

(From Yao and Gu, Liuchao yishu. )

Others had characterized Wang Xizhi as "now drifting like a floating cloud; now rearing up like a startled dragon."[91] Like celestials, the physical grace and elegance of men was a function of their inherent nature.

The Mao Shan texts were sacred, and so was their transmission. It was therefore crucial that the genuinely revealed manuscripts be weeded from the many forgeries in circulation by the late fifth century, and the Southern Qi rulers (like their Liu-Song predecessors) had a distinctly vested interest in encouraging the scholarly enterprise of collection, collation, and textual analysis that was required. For the texts, and their proper transmission, were the key to attaining the blessed state.[92]

The Ninth Patriarch of the Mao Shan sect is best known for his close relations with the first emperor of the Liang dynasty. But his work of Mao Shan scholarship and court proselytization began earlier, during the Southern Qi dynasty.[93] Poet, courtier, alchemist, and scholar, Tao Hongjing represented the new Daoist gentleman, at ease both at court and in reclusion. He received his first official appointment directly from the Qi emperor, Gao, and we learn from his

45.

Celestial.

Detail, rubbing of a brick relief mural, tomb at

Jinjiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Fifth century A.D.

(Photograph courtesy of Amy and Martin J. Powers.)

biography that he loved to play the qin and chess, that he was a skillful calligrapher.[94] Indeed, it was the elegant prose-style of the four thcentury revelations and the exquisite calligraphy of their transcription (as fine as Wang Xizhi's), we are told, that first attracted his attention to the manuscripts.[95] Although Tao Hongjing's intimations of immortality began in childhood, the ultimate lodging of his faith awaited, it would seem, an aesthetic stimulus.

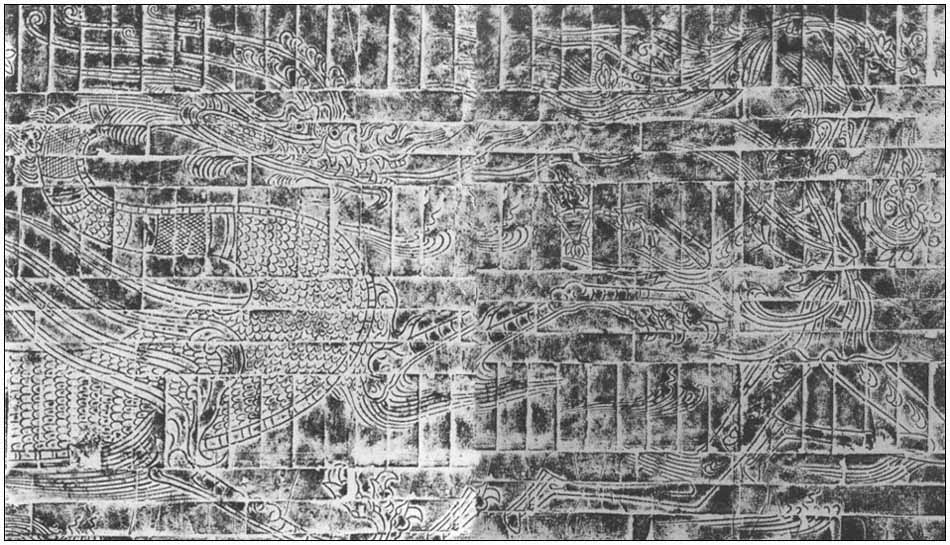

46.

Musicians on Horseback.

Detail, rubbing of a brick relief mural, west wall,

tomb at Jinjiacun, Danyang county, Jiangsu province. Fifth century A.D.

Nanjing Museum. (Photograph courtesy of James and Nicholas Cahill.)

The most distinctive feature of the sacred texts of the Heaven of Supreme Purity (Shangqing jing ), one that distinguishes them so remarkably from earlier texts of the Daoist Canon, is their literary quality.[96] The themes themselves—journeys through the Heavens, visits with nonterrestrials, celestial repasts—were not new, any more than they had been to Ruan Ji or Xi Kang. It is, rather, the poetic treatment, the style, that is new for such texts. Many aspects of this style can be traced to the literature of the early third century and specifically to the works of Xi Kang and Ruan Ji.[97]

It is here, where religion and literature join, that a new layer of significance accrues to the Seven Worthies portraits. For cultivated gentlemen concerned with the tenets of the new persuasion, familiar as they were with the old stories as well as with the literary output of our exemplars, there must have been a new resonance.[98] By this time the literature and philosophy of Wei-Jin were classics, studied by every educated man. Ruan Ji's famous prose-poem on the wanderings of the Great Man, or Xi Kang's concern with nourishing life, his

invitations to stroll hand in hand in the Supreme Purity or to ascend to the Purple Court—these were the very stuff of revelation.[99] The anecdotes of Ruan Ji's whistling, Xi Kang's forge, encounters with old men of the mountains—these random bits of tradition acquired a new emphasis, from the fifth-century point of view.[100] They signaled a search for the Way by these famous men and linked them with Daoist adepts. The recluse Zong Ce, for example, who yearned to roam in mountains and who repeatedly refused requests to serve the imperial family, painted a picture of Ruan Ji meeting the hermit of Sumen and sat facing it.[101] Tao Hongjing, in his redaction of a portion of the Mao Shan texts (the Zhengao ), included in his list of Daoist adepts Sun Deng, identifying him as the one Xi Kang met in the mountains. Sun Deng, added Tao, was also a whistler.[102] The Zhengao also referred to Xi Kang's Gaoshi zhuan and noted that Xi Kang had copied sacred texts.[103]

It is unlikely that Mao Shan adherents believed that the Seven Worthies, or any one of them, had already entered the ranks of The Perfected, the highest realm of immortality. Xi Kang, for example, when viewed from the new vantage as an adept who strove for purification, would have been understood as one whose execution—deliverance from the corpse by means of a military weapon (bingjie )—resulted only in imperfect purification.[104] As such, however, he could have become an immortal at a lower level, while attainment of the highest state lay before him, in the future. Nor were the seemingly wordly involvements of such as Shan Tao or Wang Rong a bar to attainment of the Way, for it was no longer necessary to withdraw to the mountains to achieve immortality. The aristocratic adept could be a recluse at court and withdraw into himself. In addition to more traditional means, the pursuit of immortality now also authorized the interior search (meditation and visualization). The heart/mind was as effective a terrain as the mountain. Wherever he was, the adept need only be sincere in his heart/mind, firm in his rectitude, and the Dao would come.[105]

Far from seeing contradictions in the wayward strands of the Seven Worthies' lives and traditions, the Mao Shan adept could weave them into a new mantle. Shan Tao and Wang Rong were really pure and unsullied by their worldly contacts. Xi Kang, even after corporeal death, continued his spiritual progression. If the new mantle of belief fit the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi, it fit many who attended court funerals.

What they beheld in the arrangement of the murals was their own

future. The Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi are at the same level as the winged xian, who, in the Mao Shan hierarchy, have been reduced to lower-level immortals.[106] Above them, light as air, soar the celestials, visual hints of future glory. The portrait-mural itself—only men and trees, out of time and out of three-dimensional space; the slender (i.e., weightless) bodies and fluttering garments, so appropriate for those who have been roaming the heavens and have just now alighted for rest—is ideal for arousing and absorbing new associations. Unruffled, composed—how like the celestials they are! How like them are the celestials!

The very style of the forms, those thin, raised lines that contour only the essential, seems almost a deliberate choice. Indeed, it lacks the capability for conveying bulk: an artist cannot create the illusion of three-dimensional forms using only this technique. If a sense of weight—volume, solidity—had been pleasing to patrons, artists and craftsmen would have worked in a different style, as they so often did in the Han dynasty. We have only to look at the impressive modeling of the Eastern Jin relief bricks produced not far from Danyang to know that other styles were available if wanted.[107] Some of the floral reliefs in the Danyang tombs—for example, the embossed petals next to the xian —also convey a sense of bulk by their modeling.

That style has meaning is superbly exemplified by these portraits. For patrons who valued cultivated refinement and who yearned to soar, what other style could have been more appropriate?

Men of an earlier time characterized all the Seven Worthies as men of inner detachment, whose spontaneous but self-possessed behavior was the external sign of their inner purity. Later men, Shen Yue and Liu Xie for example, continued to see at least Ruan Ji and Xi Kang in that light, accepting even the others as like-minded companions. For Mao Shan adherents, also, it was the "inner detachment"—a purity for which the adept had to strive—that was the key to the Way.[108] It is not unreasonable to suggest that the Seven Worthies (and assuredly Rong Qiqi) had by this date achieved some measure of immortality in (enlightened) men's eyes.[109]

I doubt that members of the Qi imperial family arrived, like some Renaissance patrons, at the craftsmen's atelier with the Chinese counterpart of a neo-Platonic menu in hand. I do think, on the basis of what we know about the interests of the court, that patrons selected from the pool of workshop patterns images fraught with meaning, sacred and secular, for their lives. Indeed, with remarkable economy, three sets of images were linked in one chamber to arouse in those

who attended the funerals a host of multilayered associations, the full subtleties of which were likely to be grasped by only a select few. Even those of simple mind and small refinement, however, could not have failed to notice that emperors wished to be seen as worthy of admission to the Bamboo Grove, in this world and the next. It was for emperors that the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi waited, dignified but relaxed, self-possessed—as only cultivated gentlemen can wait.

"The poetic value of the simple image lies in its power to evoke endless associations regarding the essential qualities of the object in question, despite its brevity in presentation."[110] As in lyric poetry, to which this aperçu refers, the use of "simple images" in the Seven Worthies composition was the key to its survival. Had the original composition been more detailed, its figures interacting or placed unambiguously in time and space, it would have lost that simplicity whereby it aroused a host of associations in viewers, especially those capable of tracing the waves to their source, to whom the composition could reveal even the dark and hidden.

For such a one the source was not only the events, the literary works, the many traditions of the Seven Worthies and Rong Qiqi.[111] It was also a tradition of the Bamboo Grove, a tradition that became more abstract as, paradoxically, it grew in specificity of location and detail. No matter that none of the trees in any of the extant compositions resembled actual bamboo—it was by now a concept, not a reality.[112] The merest allusion to that concept, laden with the freight of history, interscribed with all that seemed most civilized, could reassure an emperor that no barbarian from the north could match him. It comforted men like Shen Yue in their darkest moments, yet, at the same time, aroused their highest expectations. It no longer even mattered, as I shall demonstrate in the next chapter, whose names were inscribed on the bricks. The composition was, quite simply, the Bamboo Grove. Everyone knew that.