3

Coda I: The Mask as Metaphor

The mask served pre-Columbian Mesoamerica in death and in life as a metaphor for the ultimate nature of reality. Mankind and all of the aspects of the natural world were finally to be seen as features of the mask worn by the eternal life-force. The gods were but varied manifestations of the essence of life which "unfolded" as masks into man's world, and man himself, through ritual, could emerge from the spirit and merge with it again, with death providing the final assimilation. It is no wonder then that Mesoamerica used the mask as the central metaphor for its spiritual vision.

It is thus amazingly fitting that the mask played a prominent symbolic part in the final collapse of the tradition to which it was central. As Cortès and his troops rested on their ships before their march from the coast of Veracruz toward Tenochtitlán, Moctezuma, believing on the basis of a series of omens that those men were destructive apparitions from the world of the spirit, had to decide how to deal with them and protect his people. He made what must have seemed to Cortés a strange decision but one that we can understand as the only proper one from his point of view. He sent with his emissaries the regalia that would enable these apparitions to manifest themselves in their true form, a form in which they would become comprehensible in Mesoamerican terms.

First was the array of Quetzalcóatl: a serpent mask made of turquoise mosaic; a quetzal feather head fan; a plaited neck band of precious green stone beads, in the midst of which lay a golden disc; and a shield with bands of gold crossing each other, or with bands of gold crossing other bands of sea shells, with spread quetzal feathers about the lower edge and with a quetzal feather flag; and a mirror upon the small of the back, with quetzal feathers, and this mirror for the small of the back was like a turquoise shield, of turquoise mosaic-encrusted with turquoise, glued with turquoise; and green stone neck bands, on which were golden shells; and then the turquoise spear thrower, which had on it only turquoise with a sort of serpent's head; it had the head of a serpent; and obsidian sandals.

The second gift which they went offering him was the array of Tezcatlipoca—the headpiece of feathers, with stars of gold; and his golden shell earplugs; and a necklace of sea shells; and the breast ornament decorated and fringed with small shells; and the sleeveless jacket painted with a design, with eyelets on its border, and fringed with feathers; and a mantle with blue knots, which was called tzitzilli, grasped by the corners in order to tie it across the back; also, over it, a mosaic mirror lying on the small of the back; and, as another thing, golden shells bound on the calves of the legs; and one more thing, white sandals.

Third was the adornment of the lord of Tlalocan: the headdress of quetzal and heron feathers, replete with quetzal feathers. It had quetzal feathers and was blue-green; blue-green was overspread. And over it gold interspersed with shells. And green stone were his serpent-shaped earplugs. There were his sleeveless jacket, with a design of green stone; his neck ornament, his plaited, green stone neck band with also a golden disc. Also he had a mirror at the small of his back, as hath been told; and likewise he had rattles and a cape with red rings on the border, which was tied on; and shells of gold for his ankles; and his serpent staff was made of turquoise.

Fourth, likewise the array of this same

Quetzalcóatl was yet another thing: the pointed ocelot skin cap, with pheasant feathers; a very large green stone at the top, which was fixed at the tip; and round, turquoise mosaic earplugs, from which were hanging curved sea shells fashioned of gold; and a plaited green stone neck band in the midst of which there was likewise a golden disc; and a cape with red border which was tied on; likewise, golden shells used upon his ankles; and a shield with a golden disc in the center, and spread quetzal feathers along its lower rim, and also with a quetzal feather banner. He had the curved staff of the wind god, hooked at the top, and white precious stone stars spread over it; and his foam sandals.

Behold, these were all the things called the array of the gods.[1]

On reaching Cortés's ship, the messengers were taken aboard, and they "adorned the Captain himself; they put on him the turquoise mosaic serpent mask" (pl. 58) and the other regalia of the god. But as the messengers immediately discovered and as Moctezuma was to learn soon enough, these Europeans were not beneficent gods. After asking the emissaries whether they had more gifts, Cortes "commanded that they be bound" and arranged for them to observe the firing of "the great lombard gun." They were awed by its destructive power, a power that was unfortunately as symbolic of the European sense of reality as the mask of the gods was of Moctezuma's.[2]

With biting irony, Sahagún's informants follow the description of the array of the gods with a description of the array of Cortés and his men:

All iron was their war array. They clothed themselves in iron. They covered their heads with iron. Iron were their swords. Iron were their crossbows. Iron were their shields. Iron were their lances. . . .

And they covered all parts of their bodies. Alone to be seen were their faces—very white. They had eyes like chalk; they had yellow hair, although the hair of some was black. Long were their beards, and also yellow; they were yellow-bearded.[3]

In the contrast between the regalia of the gods and that of the troops, we can discern the essential contrast between the European and the American conceptions of reality, a contrast clearly not lost on Sahagún and his informants.[4] While the peoples of Mesoamerica saw reality as the constant interpenetration of different planes of existence, planes anchored in the extremes of the unapproachable life-force, on the one hand, and the world of nature, on the other, Cortés and his men saw reality as essentially material, something to be conquered and exploited. The world of the spirit was, for them, a separate domain. In this fallen world, they had been given dominion. In the clash of these essentially different views of reality, the simplicity of the conception of the Conquistadores prevailed. They were not burdened with the complexity that came from attributing material events to spiritual causes. Octavio Paz has said of this unequal encounter that "for two thousand years the Mesoamerican culture lived and grew alone; their encounter with the Other came too late and under conditions of terrible inequality. For that they were destroyed."[5]

Cp. 1.

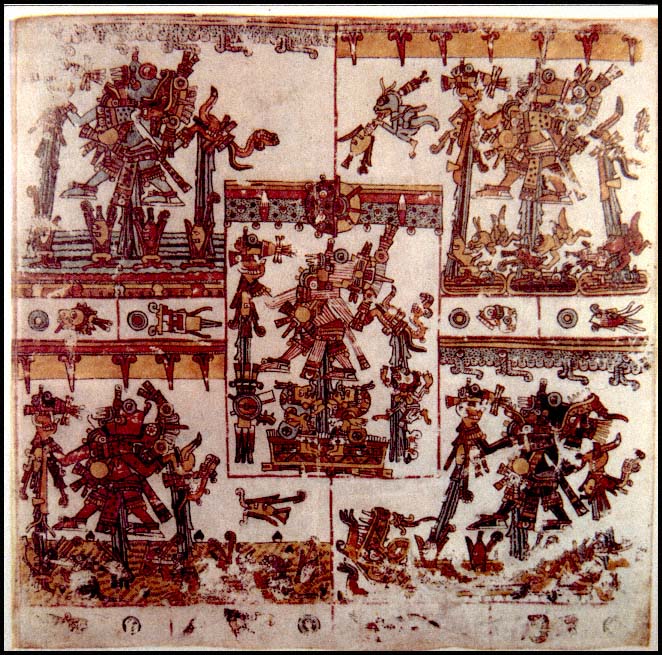

Tlalocs, page 27 of the Codex Borgia (reproduced by permission of

Fondo de Cultura Económica, México).

a

b

Cp. 2.

a. "Lightning Tlaloc," mural painting, Tetitla, Teotihuacán; b. Tlaloc, middle border

of the Tlalocan mural, Tepantitla, Teotihuacán.

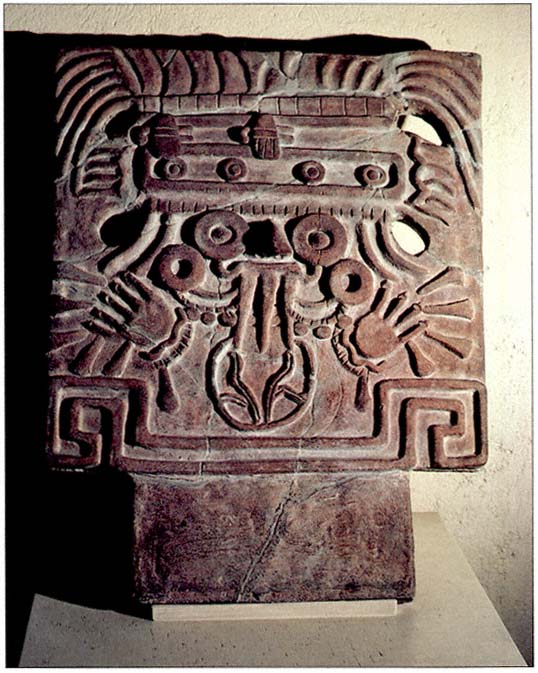

Cp. 3.

Tlaloc, relief on a merlon, Teotihuacán (Museo de la Zona Arqueológica de Teotihuacán).

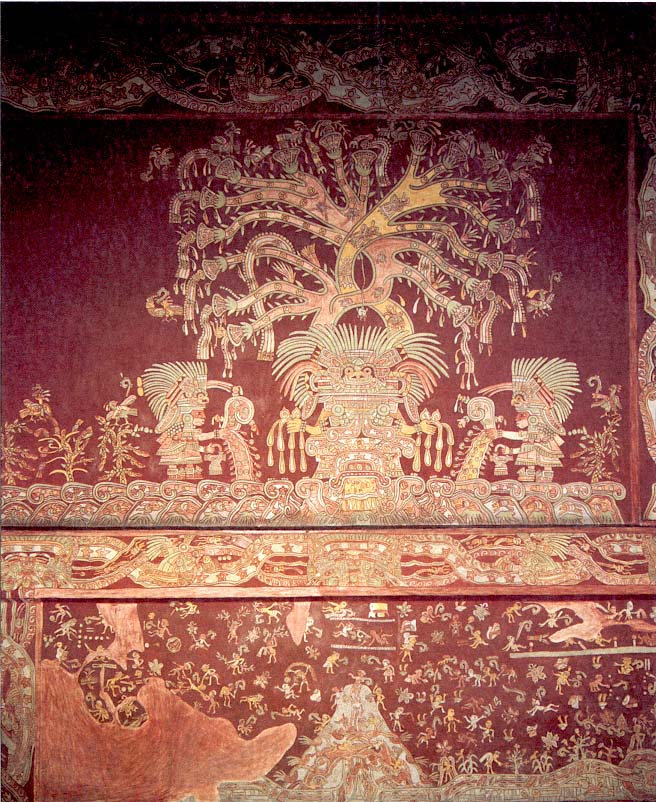

Cp. 4.

Tlalocan mural, Tepantitla, Teotihuacàn (reproduction in the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

a

b

Cp. 5.

Abstract Tlaloc murals: a. Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlán; b. Street of the Dead, Teotihuacán.

Cp. 6.

Chac, tripod plate (private collection, photograph copyright Justin Kerr 1981, reproduced by permission).

Cp. 7.

Chac mask, carved stone mosaic, facade of the Palace, Labná, Yucatán.

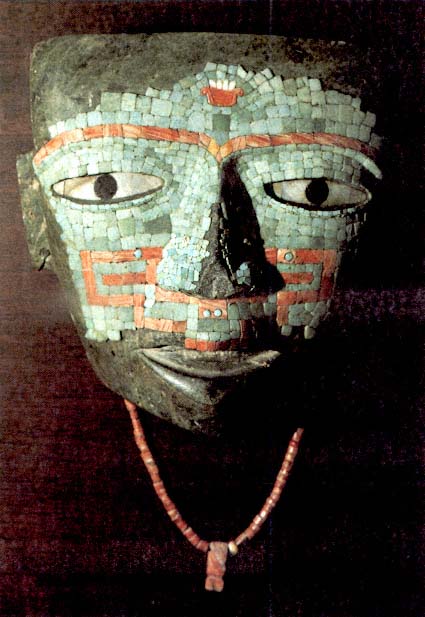

Cp. 8.

Mosaic covered stone funerary mask, culture of Teotihuacán, Texmilincán, Guerrero

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico).

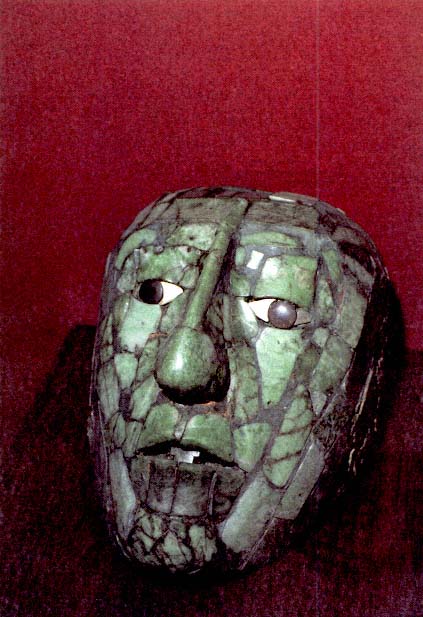

Cp. 9.

Jade mosaic funerary mask of Pacal, Temple of Inscriptions, Palenque

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México).

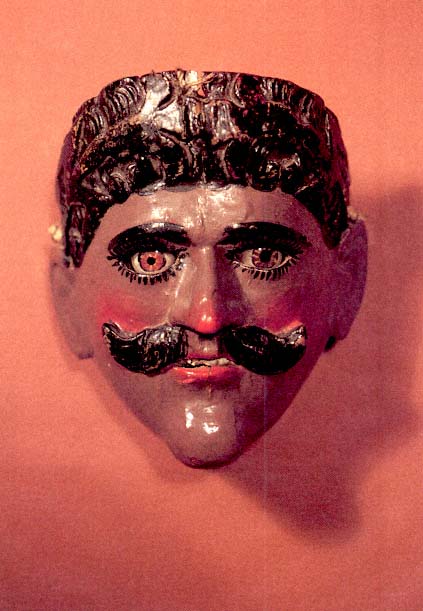

Cp. 10.

Although this is the mask of an Indian in the Dance of the Conquest, the European features

themselves suggest the syncretic nature of the drama. This mask is from

the Moreria of Pedro Antonio Tistoj M., San Cristóbal Totonicapán, Guatemala

(collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

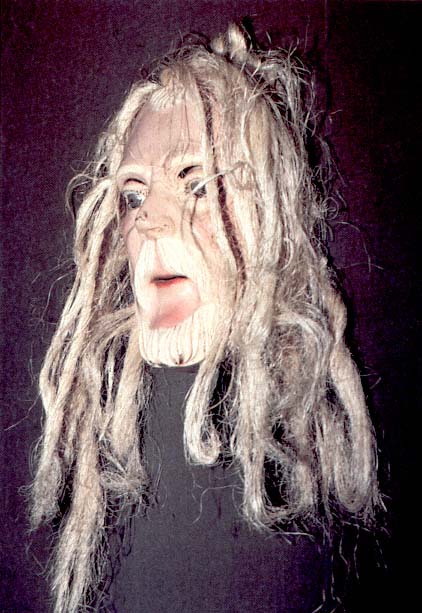

Cp. 11.

Mask of a Hermit in the Pastorela drama as performed in Ichan, Michoacan

(collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

Cp. 12.

Mask of a Tigre, Zitlala, Guerrero (collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

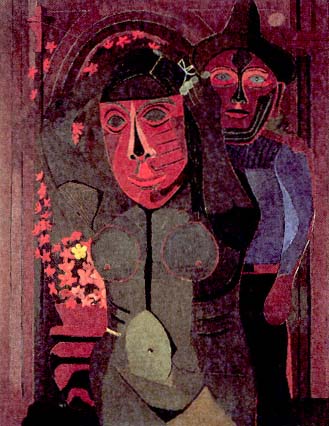

Cp. 13.

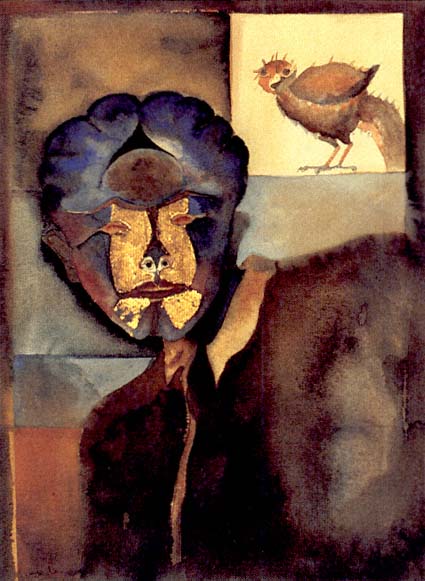

Rufino Tamayo, Carnaval, gouache on paper, 1941

(The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., reproduced by permission).

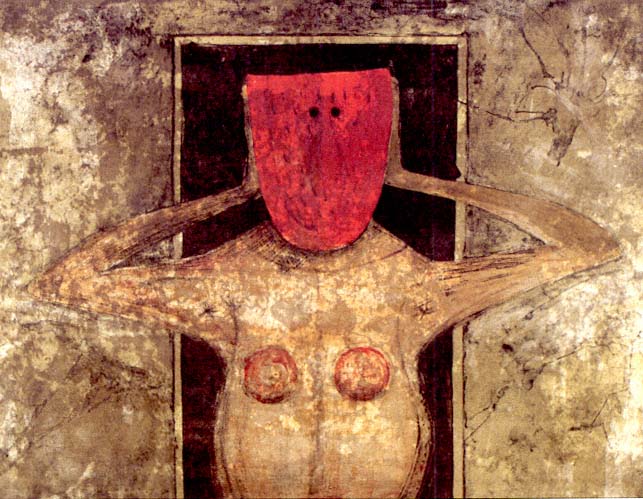

Cp. 14.

(below) Rufino Tamayo, Masque Rouge, lithograph, 1973 (collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

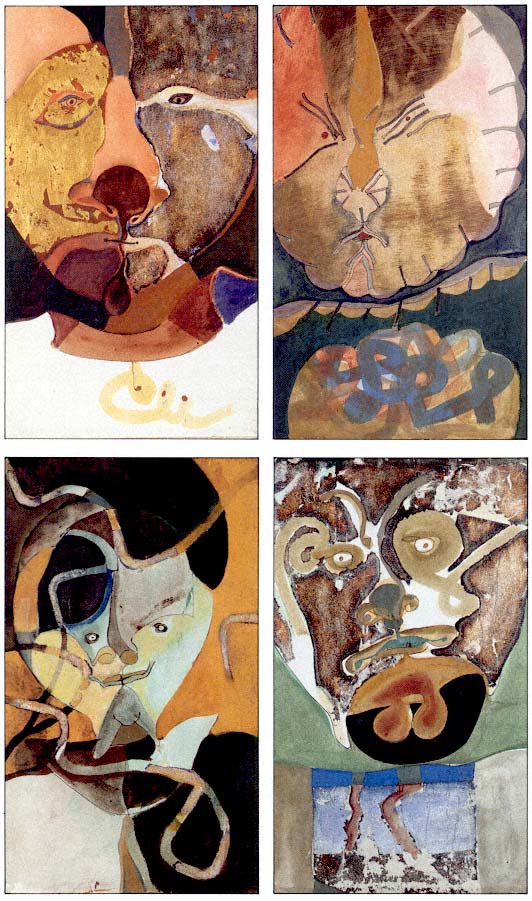

Cp. 15.

Francisco Toledo, Autoretratos-Mascaras, gouache on paper, ca. 1965 (private collection;

photograph courtesy Mary-Anne Martin/Fine Art, New York).

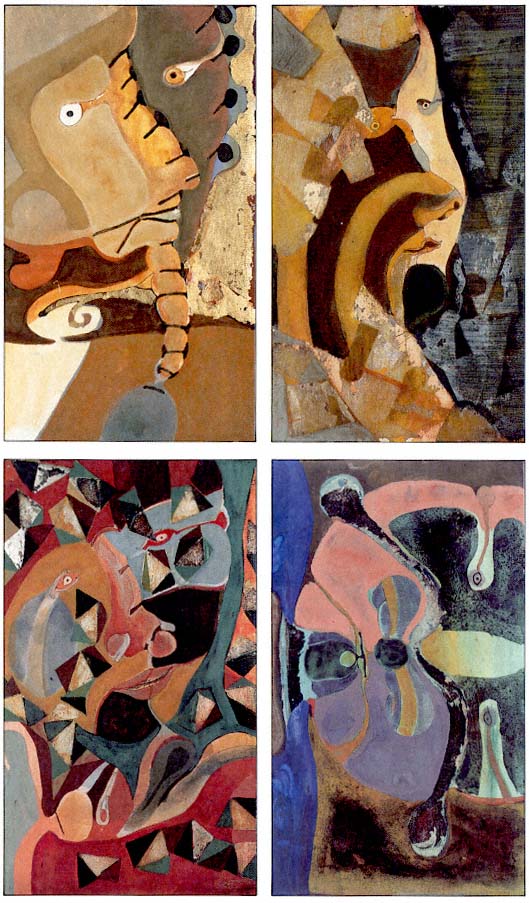

Cp. 16.

Francisco Toledo, Autoretrato, watercolor and gold leaf

on paper, ca. 1975 (collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).