PART THREE—

GENRE

The first two articles in this section have a de facto thematic relationship: Noël Carroll's "Nightmare and the Horror Film" (1981) and J. P. Telotte's "Human Artifice and the Science Fiction Film" (1983). That science fiction and horror film genres intermix and overlap—and not for the first time in Alien (1979)—is perhaps more widely accepted now than it was when these articles were written. Thus both articles discuss Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde , and Invasion of the Body Snatchers , among other films. What most sharply differentiates the articles are their theoretical orientations, and how these organize the arguments of each.

Carroll notes that the horror and science fiction film are currently in the ascendance because they correspond to a moment of American history in which "feelings of paralysis, helplessness, and vulnerability (hallmarks of the nightmare) prevail." He proposes to extend some points made by Ernest Jones in On the Nightmare (1951) to the imagery of the horror/science fiction film. Noting that nightmare has long been associated with horror literature and film, he points to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein , Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto , and R. L. Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as works whose genesis was "fitful sleep" or outright nightmare. Carroll does not adhere to psychoanalysis as a general hermeneutic method, but finds it applicable here because "as a matter of social tradition, psychoanalysis is more or less the lingua franca of the horror film and thus the privileged critical tool for discussing the genre." (Thus Carroll arrives at a Freudian method by way of something like Hume's reliance on social convention.)

Jones argues that the object seen in the nightmare is frightful or hideous because the underlying wish is not permitted in its naked form, so that the dream is a compromise between the wish and the fear belonging to its inhibition. Carroll sees this conflict between attraction and repulsion as corrective to approaches that emphasize only one side of this duality; allegorical readings of

horror films, for instance, tend not to acknowledge the repellent aspects of the genre. Nevertheless, Carroll "modifies" Jones, whom he calls "a hardline Freudian," by studying the nightmare conflicts embodied in the horror film as "having broader reference than simply sexuality." (It should be noted that since writing this piece, Carroll has abandoned the use of a psychoanalytic framework for dealing with this material and has approached it through the cognitive theory of emotions as set forth in his book The Philosophy of Horror .)

Telotte focuses on "the number of recent films that take as their major concern . . . the potential doubling of the human body and thus the literal creation of a human artifice." These include the remakes of Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Thing, Blade Runner , and Alien . These films reflect uneasiness about human identity, and what makes us human, in an era of cloning and other technologies of human duplication. Telotte begins his survey with the destructive android look-alike of Maria in Metropolis and then proceeds to the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers , in which individuals are duplicated "cell for cell, atom for atom." Frankenstein , subtitled The Modern Prometheus , points to the presence in the genre of a Faustian drive for knowledge or power, a dangerous impulse behind the fascination with the power of science. (There is a split between good and bad science in some of these films.) Telotte makes a fascinating point concerning the "lingering Cartesian dualism" between mind and body, thinking and feeling: the fashioning of other bodies, other forms of the self, only reinforces that split and reasserts the hegemony of mind over body.

He sees the monster in Alien , invulnerable to normal human defenses, as metaphoric of "some flaw within man." John Carpenter's The Thing , which can imitate the form of any human, entails what René Girard discusses as the "close scrutiny" that reveals man's double to be monstrous. When only a black and a white character remain at the end of the film, each eyes the other with the conviction that he is a double fashioned by the alien, which points up the distrust and fear that mark modern society and particularly, of course, its race relations. Telotte's longest discussion, which carries his exploration of the artificial doubling of the human to its farthest point, concerns, not surprisingly, Blade Runner .

In "The Sacraments of Genre: Coppola, DePalma, Scorsese," Leo Braudy contrasts André Bazin's definition of neorealism with the orientation of the three Italian-American directors of his title, whose commitment is to genre, which the author calls "the prime seedbed of American films." Concerning an unrealistic but symbolically potent juxtaposition of rooms in Rossellini's Open City , Braudy notes that it is "an incantatory moment, a mode of suprarealistic

perception that I would like to call a sacramentalizing of the real, not so that it be worshipped but so that its spiritual essence, whether diabolical or holy, inflect what is otherwise a discrete collection of objects in space."

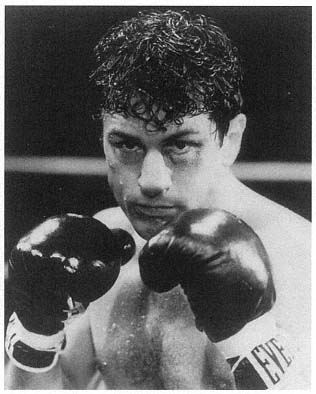

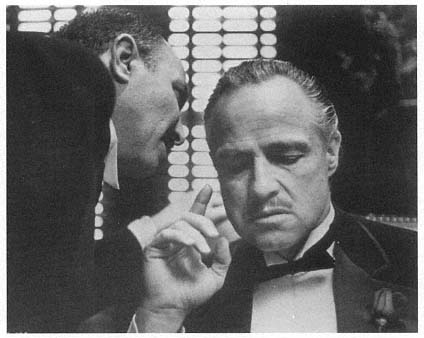

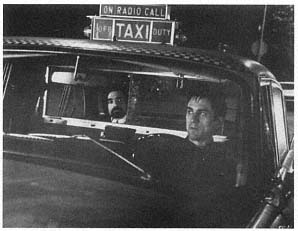

For all the differences among his three directors, Braudy finds in all of them a sense of the importance of ritual narratives, the significance of ritual objects, and a tendency to mine the visual world for its transcendental potential. Objects, people, places, and stories are irradiated by the meaning from within, which the directors seek to unlock. In the work of Francis Ford Coppola, the sense of genre is attached to a feeling for family rituals, including betrayals. As Braudy notes, "Always there is a dream of camaraderie, and invariably that dream turns sour." Orson Welles is Coppola's directorial antecedent, but, unlike Welles, he is unwilling to question his own role as director and Wunderkind . Brian DePalma's work is concerned with the interplay between the technological future and the mythic past; like Alfred Hitchcock, his principal inspiration, he is fascinated with significant objects, which in the younger director's work are close to icons. He is also concerned with the power of the mind to move objects, especially in Carrie and The Fury . His bright young people, like the computer whiz in Dressed to Kill , can never reach the greatness of the past, which they turn instead into a machinelike efficiency. Martin Scorsese explores the final and perhaps most pervasive aspect of the intersection of film with Catholicism—the structure of sainthood. Just as Mean Streets says you make up for your sins not in church but in the street and at home, so the director places "the performer/saint/devil" at the center of films such as Taxi Driver, Raging Bull , and The King of Comedy . By casting himself in violent or subservient roles in these films, Scorsese also questions his own authority as director and makes himself complicit in the stories he tells.

Scott MacDonald's "Confessions of a Feminist Porn Watcher" is sacramental in name only—there is no quest for transcendence here. To call his participation in his account complicit does not begin to reveal its courageous, highly personal nature. But what the confessional mode masks is how much the article tells us about porn as an institution and a genre. For this reason alone, a second reading is advantageous. It does not dissolve the article's subjective cast, but reveals a good deal more information and insight through that framework.

The point of departure for the article was a screening of an anti-porn film polemic/documentary and several reviews of it, notably B. Ruby Rich's challenge "for the legions of feminist men" to undertake the analysis of why men like porn. MacDonald, in a remarkably thoughtful way, takes up the challenge. If, as the film said, porn reinforces male domination of women, why then do men pay for fantasy material to this effect; and why is there so much fear and

embarrassment about going to porn houses or arcades? MacDonald notes also that "direct sexual experience with a conventionally attractive woman is, or seems, out of the question for many men." Porn provides a compromise by making visual knowledge of such an experience possible. His most trenchant argument has to do with the "unprovoked leers and comments" that women complain of. MacDonald will go to considerable lengths to avoid intruding in this way, but "I have to fight the urge to stare all the time. Some of the popularity of pornography even among men who consider themselves feminists may be a function of its capacity to provide a form of unintrusive leering."

To David James in "Hardcore: Cultural Resistance in the Postmodern," the pornography which Scott MacDonald occasionally seeks out is "industrial" porn, which James also calls "commodity pornography," which he opposes unfavorably to The Best of Amateur Erotic Video Volume II , a compilation of four tapes, each fifteen to twenty minutes long, self-photographed and self-produced by middle-class, heterosexual, white couples. Although his article is anything but a confession, James does forthrightly admit that he finds the amateur erotic video compilation, which he greatly prefers on theoretical grounds, "less arousing and so less desirable than its industrial counterpart."

James's article begins with a bleak survey arguing the destruction or co-optation of working-class movements in the United States since the 1930s; the collapse of mobilization around Third World struggles of decolonization since the end of the Vietnam War; and, most recently, the politically effective rollback of basic Marxist concepts, even that of class. (The article appeared in Winter 1988–89.) The turning to art and culture as a possible refuge for utopian thinking has been a plausible resort at least since the Frankfurt School. The avant-garde film movement in the sixties was an effective refuge of this kind; this was followed by a brief period of alternative video, but later emanations of these movements and of every other potentially oppositional movement has been absorbed into the cultural industry. James identifies two possibilities for opposition: the amateur erotic video movement, which he contrasts favorably with commodity porn in a long, frequently brilliant comparison; and a genuinely local, self-produced alternative punk rock movement that is explicitly and blisteringly political. For those whose exposure is limited to MTV, he notes, this movement is an enormous and pungent surprise.

Nightmare and the Horror Film:

The Symbolic Biology of Fantastic Beings

Noël Carroll

Vol. 34, no. 3 (Spring 1981): 16–25.

Whereas the Western and the crime film were the dominant genres of the late sixties and early seventies, horror and science fiction are the reigning popular forms of the late seventies and early eighties. Launched by blockbusters like The Exorcist and Jaws , the cycle has flourished steadily; it seems as unstoppable as some of the demons it has spawned. The present cycle, like the horror cycle of the thirties and the science fiction cycle of the fifties, comes at a particular kind of moment in American history—one where feelings of paralysis, helplessness, and vulnerability (hallmarks of the nightmare) prevail. If the Western and the crime film worked well as open forums for the debate about our values and our history during the years of the Vietnam war, the horror and science fiction film poignantly express the sense of powerlessness and anxiety that correlates with times of depression, recession, Cold War strife, galloping inflation, and national confusion.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the basic structures and themes of these timely genres by extending some of the points made in Ernest Jones's On the Nightmare .[1] Jones used his analysis of the nightmare to unravel the symbolic meaning and structure of such figures of medieval superstition as the incubus, vampire, werewolf, devil, and witch. Similarly, I will consider the manner in which the imagery of the horror/science fiction film is constructed in ways that correspond to the construction of nightmare imagery. My special, though not exclusive, focus will be on the articulation of the imagery of horrific creatures—on what I call their symbolic biologies. A less pretentious subtitle for this essay might have been "How to make a monster."

Nightmare and the Horror Film

Before beginning this "unholy" task, some qualifications are necessary. Throughout this article I will slip freely between examples drawn from horror

films and science fiction films. Like many connoisseurs of science fiction literature, I think that, historically, movie science fiction has evolved as a subclass of the horror film. That is, in the main, science fiction films are monster films, rather than explorations of grand themes like alternate societies or alternate technologies.

Secondly, I am approaching the horror/science fiction film in terms of a psychoanalytic framework, though I do not believe that psychoanalysis is a hermeneutic method that can be applied unproblematically to any kind of film or work of art. Consequently, the adoption of psychoanalysis as an interpretive tool in a given case should be accompanied by a justification for its use in regard to that case. And in this light, I would argue that it is appropriate to use psychoanalysis in relation to the horror film because within our culture the horror genre is explicitly acknowledged as a vehicle for expressing psychoanalytically significant themes such as repressed sexuality, oral sadism, necrophilia, etc. Indeed, in recent films, such as Jean Rollin's Le Frisson des Vampires and La Vampire Nue , all concealment of the psychosexual subtext of the vampire myth is discarded. We have all learned to treat the creatures of the night—like werewolves—as creatures of the id, whether we are spectators or film-makers. As a matter of social tradition, psychoanalysis is more or less the lingua franca of the horror film and thus the privileged critical tool for discussing the genre. In fact horror films often seem to be little more than bowdlerized, pop psychoanalysis, so enmeshed is Freudian psychology with the genre.

Nor is the coincidence of psychoanalytic themes and those of the horror genre only a contemporary phenomenon. Horror has been tied to nightmare and dream since the inception of the modern tradition. Over a century before the birth of psychoanalysis Horace Walpole wrote of The Castle of Otranto ,

I waked one morning, in the beginning of last June, from a dream, of which all I could recover was, that I had thought myself in an ancient castle (a very natural dream for a head like mine filled with Gothic story) and that on the uppermost bannister of a great staircase I saw a gigantic hand in armour. In the evening I sat down, and began to write, without knowing in the least what I intended to say or relate. The work grew on my hands and I grew so fond of it that one evening, I wrote from the time I had drunk my tea, about six o'clock, till half an hour after one in the morning, when my hands and fingers were so weary that I could not hold the pen to finish the sentence.

The assertion that a given horror story originated as a dream or nightmare occurs often enough that one begins to suspect that it is something akin to invoking a muse (or an incubus or succubus, as the case may be). Mary Shelley's

Frankenstein , Bram Stoker's Dracula , and Henry James's "The Jolly Corner" are all attributed to fitful sleep as is much of Robert Louis Stevenson's output—notably Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde .[2] In what sense these tales were caused by nightmares or modeled on dreams is less important than the fact that the nightmare is a culturally established framework for presenting and understanding the horror genre. And this makes the resort to psychoanalysis unavoidable.

A central concept in Jones's treatment of the imagery of nightmare is conflict. The products of the dreamwork are often simultaneously attractive and repellent insofar as they function to enunciate both a wish and its inhibition. Jones writes, "The reason why the object seen in a Nightmare is frightful or hideous is simply that the representation of the underlying wish is not permitted in its naked form so that the dream is a compromise of the wish on the one hand and on the other of the intense fear belonging to the inhibition."[3] The notion of the conflict between attraction and repulsion is particularly useful in considering the horror film, as a corrective to alternate ways of treating the genre. Too often, writing about this genre only emphasizes one side of the imagery. Many journalists will single-mindedly underscore only the repellent aspects of a horror film—rejecting it as disgusting, indecent, and foul. Yet this tack fails to offer any account of why people are interested in seeing such exercises.

On the other hand, defenders of the genre or of a specific example of the genre will often indulge in allegorical readings that render their subjects wholly appealing and that do not acknowledge their repellent aspects. Thus, we are told that Frankenstein is really an existential parable about man thrown-into-the-world, an "isolated sufferer."[4] But if Frankenstein is part Nausea , it is also nauseating. Where in the allegorical formulation can we find an explanation for the purpose of the unsettling effect of the charnel-house imagery? The dangers of this allegorizing/valorizing tendency can be seen in some of the work of Robin Wood, the most vigorous champion of the contemporary horror film. Sisters , he writes, "analyzes the ways in which women are oppressed within patriarchal society on two levels which one can define as professional (Grace) and the psychosexual (Danielle/Dominque)."[5]

One wants to say "perhaps but . . ." Specifically, what about the unnerving, gory murders and the brackish, fecal bond that links the Siamese twins? Horror films cannot be construed as completely repelling or completely appealing. Either outlook denies something essential to the form. Jones's use of the concept of conflict in the nightmare to illuminate the symbolic portent of the monsters of superstition, therefore, suggests a direction of research into the study of the horror film which accords with the genre's unique combination of repulsion and delight.

To conclude my qualifying remarks, I must note that as a hardline Freudian, Jones suffers from one important liability; he over-emphasizes the degree to

which incestuous desires shape the conflicts in the nightmare (and, by extension, in the formation of fantastic beings) and he claims that nightmares always relate to the sexual act.[6] As John Mack has argued, this perspective is too narrow; "the analysis of nightmares regularly leads us to the earliest, most profound, and inescapable anxieties and conflicts to which human beings are subject: those involving destructive aggression, castration, separation and abandonment, devouring and being devoured, and fear regarding loss of identity and fusion with the mother."[7] Thus, modifying Jones, we will study the nightmare conflicts embodied in the horror film as having broader reference than simply sexuality.

Our starting hypothesis is that horror film imagery, like that of the nightmare, incarnates archaic, conflicting impulses. Furthermore, this assumption orients inquiry, leading us to review horror film imagery with an eye to separating out thematic strands that represent opposing attitudes. To clarify what is involved in this sort of analysis, an example is in order.

When The Exorcist first opened, responses to it were extreme. It was denounced as a new cultural low at the same time that extra theaters had to be found in New York, Los Angeles, and other cities to accommodate the overflow crowds. The imagery of the film touched deep chords in our national psyche. The spectacle of possession addressed and reflected profound fears and desires never before explored in film. The basic infectious terror in the film is that personal identity is a frail thing, easily lost. Linda Blair's Regan, with her "tsks" and her "ahs," is a model of middle-class domesticity, a vapid mask quickly engulfed by repressed powers. The character is not just another evil child in the tradition of The Bad Seed . It is an expression of the fear that beneath the self we present to others are forces that can erupt to obliterate every vestige of self-control and personal identity.

In The Exorcist , the possibility of the loss of self is greeted with both terror and glee. The fear of losing self-control is great, but the manner in which that loss is manifested is attractive. Once possessed, Regan's new powers, exhibited in hysterical displays of cinematic pyrotechnics, act out the imagery of infantile beliefs in the omnipotence of the will. Each grisly scene is a celebration of infantile rage. Regan's anger cracks doors and ceilings and levitates beds. And she can deck a full-grown man with a flick of a wrist. The audience is aghast at her loss of self-control, which begins fittingly enough with her urinating on the living room rug, but at the same time its archaic beliefs in the metaphysical prowess of the emotions are cinematically confirmed. Thought is given direct causal efficacy. Regan's feelings know no bounds; they pour out of her, tearing her own flesh apart with their intensity and hurling people and furniture in every direction. Part of the legacy of The Exorcist to its successors—like Carrie, The Fury , and Patrick , to name but a few titles in this rampant subgenre—is the fascination with telekinesis, which is nothing but a cinematic

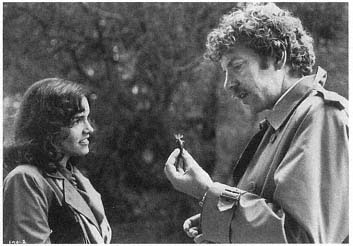

"Figures that are simultaneously attractive and replusive":

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde .

metaphor of the unlimited power of repressed rage. The audience is both drawn to and repelled by it—we recognize such rage in ourselves and superstitiously fear its emergence, while simultaneously we are pleased when we see a demonstration, albeit fictive, of the power of that rage.[8]

Christopher Lasch has argued that the neurotic personality of our time vacillates between fantasies of self-loathing and infantile delusions of grandeur.[9] The strength of The Exorcist is that it captures this oscillation cinematically. Regan, through the machinations of Satan, is the epitome of self-hatred and self-degradation—a filthy thing, festering in its bed, befoulling itself, with fetid breath, full of scabs, dirty hair, and a complexion that makes her look like a pile of old newspapers.

The origins of this self-hatred imagery are connected with sexual themes. Regan's sudden concupiscence corresponds with a birthday, presumably her thirteenth. There are all sorts of allusions to masturbation: not only does Regan misuse the crucifix, splattering her thighs with blood in an act symbolic

of both loss of virginity and menstruation, but later her hands are bound (one enshrined method for stopping "self-abuse") and her skin goes bad (as we were all warned it would). Turning the head 360 degrees also has sexual connotations; in theology, it is described as a technique Satan uses when sodomizing witches. Regan incarnates images of worthlessness, of being virtually trash, in a context laden with sex and self-laceration. But the moments of self-degradation give way to images that express delusions of grandeur as she rocks the house in storms of rage. She embodies moods of guilt and rebellion, of self-loathing and omnipotence that speak to the Narcissus in each of us.

The fantastic beings of horror films can be seen as symbolic formations that organize conflicting themes into figures that are simultaneously attractive and repulsive. Two major symbolic structures appear most prominent in this regard: fusion, in which the conflicting themes are yoked together in one, spatio-temporally unified figure; and fission, in which the conflicting themes are distributed—over space or time—among more than one figure.

Dracula, one of the classic film monsters, falls into the category of fusion. In order to identify the symbolic import of this figure we can begin with Jones's account of vampires—since Dracula is a vampire—but we must also amplify that account since Dracula is a very special vampire. According to Jones, the vampires of superstition have two fundamental constituent attributes: revenance and blood sucking. The mythic, as opposed to movie, vampire first visits its relatives. For Jones, this stands for the relatives' longing for the loved one to return from the dead. But the figure is charged with terror. What is fearful is blood sucking, which Jones associates with seduction. In short, the desire for an incestuous encounter with the dead relative is transformed, through a form of denial, into an assault-attraction, and love metamorphoses into repulsion and sadism. At the same time, via projection, the living portray themselves as passive victims, imbuing the dead with a dimension of active agency that permits the "victim" pleasure without blame. Lastly, Jones not only connects blood sucking with the exhausting embrace of the incubus but with a regressive mixture of sucking and biting characteristic of the oral stage of psychosexual development. By negation—the transformation of love to hate, by projection—through which the desired dead become active, and the desiring living passive, and by regression—from genital to oral sexuality, the vampire legend gratifies incestuous and necrophiliac desires by amalgamating them in a fearsome iconography.

The vampire of lore and the Dracula figure of stage and screen have several points of tangency, but Dracula also has a number of distinctive attributes. Of necessity, Dracula is Count Dracula. He is an aristocrat; his bearing is noble; and, of course, through hypnosis, he is a paradigmatic authority figure. He is commanding in both senses of the word. Above all, Dracula demands obedience

of his minions and mistresses. He is extremely old—associated with ancient castles—and possessed of incontestable strength. Dracula cannot be overcome by force—he can only be outsmarted or outmaneuvered; humans are typically described as puny in comparison to him. At times, Dracula is invested with omniscience, observing from afar the measures taken against him. He also hoards women and is a harem master. In brief, Dracula is a bad father figure, often balanced off against Van Helsing. who defends virgins against the seemingly younger, more vibrant Count. The phallic symbolism of Dracula is hard to miss—he is aged, buried in a filthy place, impure, powerful, and aggressive.

The contrast with Van Helsing immediately suggests another cluster of Dracula's attributes. He does appear the younger of the two specifically because he represents the rebellious son at the same time that he is the violent father. This identification is achieved by means of the Satanic imagery that contributes to Dracula's persona. Dracula is the Devil—one film in fact refers to him in its title as the "Prince of Darkness." With few exceptions, Dracula is depicted as eternally uncontrite, bent on luring hapless souls. Most importantly, Dracula is a modern devil, which, as Jones points out, means that he is a rival to God. Religiously, Dracula is presented as a force of unmitigated evil. Dramatically, this is translated into a quantum of awesome will or willfulness, often flexed in those mental duels with Van Helsing. Dracula, in part, exists as a rival to the father, as a figure of defiance and rebellion, fulfilling the oedipal wish via a hero of Miltonic proclivities. The Dracula image, then, is a fusion of conflicting attributes of the bad (primal) father and the rebellious son which is simultaneously appealing and forbidding because of the way it conjoins different dimensions of the oedipal fantasy.

The fusion of conflicting tendencies in the figure of the monster in horror films has the dream process of condensation as its approximate psychic prototype. In analyzing the symbolic meaning of these fusion figures our task is to individuate the conflicting themes that constitute the creature. Like Dracula, the Frankenstein monster is a fusion figure, one that is quite literally a composite. Mary Shelley first dreamed of the creature at a time in her life fraught with tragedies connected with childbirth.[10] Victor Frankenstein's creation—his "hideous progeny"—is a gruesome parody of birth; indeed, Shelley's description of the creature's appearance bears passing correspondences to that of a newborn—its waxen skin, misshapen head, and touch of jaundice. James Whale's Frankenstein also emphasizes the association of the monster with a child; its walk is unsteady and halting, its head is outsized and its eyes sleepy. And in the film, though not in the novel, the creature's basic cognitive skills are barely developed; it is mystified by fire and has difficulty differentiating between little girls and flowers. The monster in one respect is a child and its creation is a birth that is presented as ghastly. At the same time, the monster is made of

waste, of dead things, in "Frankenstein's workshop of filthy creation." The excremental reference is hardly disguised. The association of the creature with waste implies that, in part, the story is underwritten by the infantile confusion over the processes of elimination and reproduction. The monster is reviled as heinous and as unwholesome filth, rejected by its creator—its father—perhaps in a way that reorchestrated Mary Shelley's feelings of rejection by her father, William Godwin.

But these images of loathesomeness are fused with opposite qualities. In the film myth, the monster is all but omnipotent (it can function as a sparring partner for Godzilla), indomitable, and, for all intents and purposes, immortal (perhaps partly for the intent and purpose of sequels). It is both helpless and powerful, worthless and godlike. Its rejection spurs rampaging vengeance, combining fury and strength in infantile orgies of rage and destruction. Interestingly, in the novel this ire is directed against Victor Frankenstein's family. And even in Whale's 1931 version of the myth the monster's definition as outside (excluded from a place in) the family is maintained in a number of ways: the killing of Maria; the juxtaposition of the monster's wandering over the countryside with wedding preparations; and the opposition of Frankenstein's preoccupation with affairs centered around the monster to the interest of propagating an heir to the family barony. The emotional logic of the tale proceeds from the initial loathesomeness of the monster, which triggers its rejection, which causes the monster to explode in omnipotent rage over its alienation from the family, which, in turn, confirms the earlier intimation of "badness," thereby justifying the parental rejection.[11] This scenario, moreover, is predicated on the inherently conflicting tendencies—of being waste and being god—that are condensed in the creature from the start. It is, therefore, a necessary condition for the success of the tale that the creature be repellent.

One method for composing fantastic beings is fusion. On the visual level, this often entails the construction of creatures that transgress categorical distinctions such as inside/outside, insect/human, flesh/machine, etc.[12] The particular affective significance of these admixtures depends to a large extent on the specific narrative context in which they are embedded. But apart from fusion, another means for articulating emotional conflicts in horror films is fission. That is, conflicts concerning sexuality, identity, aggressiveness, etc. can be mapped over different entities—each standing for a different facet of the conflict—which are nevertheless linked by some magical, supernatural, or sci-fi process. The type of creatures that I have in mind here include doppelgängers , alter-egos, and werewolves.

Fission has two major modes in the horror film.[13] The first distributes the conflict over space through the creation of doubles, e.g., The Portrait of Dorian Gray, The Student of Prague , and Warning Shadows . Structurally, what is involved in spatial fission is a process of multiplication, i.e., a charac-

Bride of Frankenstein: Elsa Lanchester and Boris Karloff

ter or set of characters is multiplied into one or more new facets each standing for another aspect of the self, generally one that is either hidden, ignored, repressed, or denied by the character who has been cloned. These examples each employ some mechanism of reflection—a portrait, a mirror, shadows—as the pretext for doubling. But this sort of fission figure can appear without such devices. In I Married a Monster from Outer Space , a young bride begins to suspect that her new husband is not quite himself. Somehow he's different than the man she used to date. And she's quite right. Her boyfriend was kidnapped by invaders from outer space on his way back from a bachelor party and was replaced by an alien duplicate. This double, however, initially lacks feelings—the essential characteristic of being human in fifties sci-fi films—and his bride intuits this. The basic story, sci-fi elements aside, resembles a very specific paranoid delusion called Capgras syndrome. The delusion involves the patient's belief that his or her parents, lovers, etc. have become minatory doppelgängers . This enables the patient to deny his fear or hatred of a loved one by splitting the loved one in half, creating a bad version (the invader) and a good one (the victim). The new relation of marriage in I Married a Monster appears to engender a conflict, perhaps over sexuality, in the wife which is expressed through the fission figure.[14] Splitting as a psychic trope of denial is the root prototype for spatial fission in the horror film, organizing conflict through the multiplication of characters.

Fission occurs in horror films not only in terms of multiplication but also in terms of division. That is, a character can be divided in time as well as multiplied in space. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and the various werewolves, cat

people, gorgons, and other changelings of the genre are immediate examples. In the horror film, temporal fission—usually marked by shape changing—is often self-consciously concerned with repression. In Curse of the Werewolf one shot shows the prospective monster behind the bars of a wine cellar window holding a bottle; it is an icon of restrained delirium. The traditional conflict in these films is sexuality. Stevenson's Jekyll and Hyde is altered in screen variants so that the central theme of Hyde's brutality—which I think is connected to an allegory against alcoholism in the text—becomes a preoccupation with lechery. Often changeling films, like The Werewolf of London or The Cat People , eventuate in the monster attacking its lover, suggesting that this subgenre begins in infantile confusions over sexuality and aggression. The imagery of werewolf films also has been associated with conflicts connected with the bodily changes of puberty and adolescence: unprecedented hair spreads over the body, accompanied by uncontrollable, vaguely understood urges leading to puzzlement and even to fear of madness.[15] This imagery becomes especially compelling in The Wolfman , where the tension between father and son mounts through anger and tyranny until at last the father beats the son to death with a silver cane in a paroxysm of oedipal anxiety.[16]

Fusion and fission generate a large number of the symbolic biologies of horror films, but not all. Magnification of power or size—e.g., giant insects (and other exaggerated animalcules)—is another mode of symbol formation. Often magnification takes a particular phobia as its subject and, in general, much of this imagery seems comprehensible in terms of Freud's observation that "the majority of phobias . . . are traceable to such a fear on the ego's part of the demands of the libido."[17]

Giant insects are a case in point. The giant spider, for instance, appeared in silent film in John Barrymore's Jekyll and Hyde as an explicit symbol of desire. Perhaps insects, especially spiders, can perform this role not only because of their resemblance to hands—the hairy hands of masturbation—but also because of their cultural association with impurity.[18] At the same time, their identification as poisonous and predatory—devouring—can be mobilized to express anxious fantasies over sexuality. Like giant reptiles, giant insects are often encountered in two specific contexts in horror films. They inhabit negative paradises—jungles and lost worlds—that unaware humans happen into, not to find Edenic milk and honey but the gnashing teeth or mandibles of oral regression. Or, giant insects or reptiles are slumbering potentials of nature released or awakened by physical or chemical alterations caused by human experiments in areas of knowledge best left to the gods. Here, the predominant metaphor is that these creatures or forces have been unfettered or unleashed, suggesting their close connection with erotic impulses. Like the fusion and fis-

sion figures of horror films, these nightmares are also explicable as effigies of deep-seated, archaic conflicts.

So far I have dwelt on the symbolic composition of the monsters in horror films, extrapolating from the framework set out by Jones in On the Nightmare in the hope of beginning a crude approximation of a taxonomy. But before concluding, it is worthwhile to consider briefly the relevance of archaic conflicts of the sort already discussed to the themes repeated again and again in the basic plot structures of the horror film.[19]

Perhaps the most serviceable narrative armature in the horror film genre is what I call the Discovery Plot. It is used in Dracula, The Exorcist, Jaws I & II, It Came From Outer Space, Curse of the Demon, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, It Came From Beneath the Sea , and myriad other films. It has four essential movements. The first is onset: the monster's presence is established, e.g., by an attack, as in Jaws . Next, the monster's existence is discovered by an individual or a group, but for one reason or another its existence or continued existence, or the nature of the threat it actually poses, is not acknowledged by the powers that be. "There are no such things as vampires," the police chief might say at this point. Discovery, therefore, flows into the next plot movement, which is confirmation. The discoverers or believers must convince some other group of the existence and proportions of mortal danger at hand. Often this section of the plot is the most elaborate, and suspenseful. As the UN refuses to accept the reality of the onslaught of killer bees or invaders from Mars, precious time is lost, during which the creature or creatures often gain power and advantage. This interlude also allows for a great deal of discussion about the encroaching monster, and this talk about its invulnerability, its scarcely imaginable strength, and its nasty habits endows the off-screen beast with the qualities that prime the audience's fearful anticipation. Language is one of the most effective ingredients in a horror film and I would guess that the genre's primary success in sound film rather than silent film has less to do with the absence of sound effects in the silents than with the presence of all that dialogue about the unseen monster in the talkies.

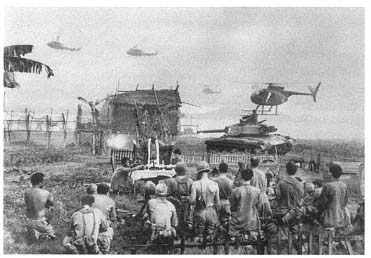

After the hesitations of confirmation, the Discovery Plot culminates in confrontation. Mankind meets its monster, most often winning, but on occasion, like the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers , losing. What is particularly of interest in this plot structure is the tension caused by the delay between discovery and confirmation. Thematically, it involves the audience not only in the drama of proof but also in the play between knowing and not knowing,[20] between acknowledgment versus nonacknowledgment, that has the growing awareness of sexuality in the adolescent as its archetype. This conflict can become very pronounced when the gainsayers in question—generals, police

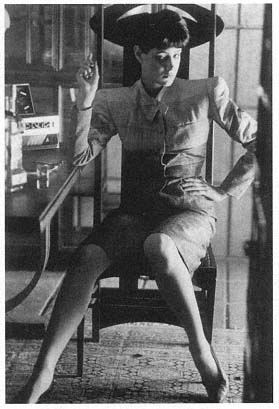

Donald Sutherland in the toils of the delayed-discovery plot:

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

chiefs, scientists, heads of institutions, etc.—are obviously parental authority figures.

Another important plot structure is that of the Overreacher. Frankenstein, Jekyll and Hyde , and Man with the X-Ray Eyes are all examples of this approach. Whereas the Discovery Plot often stresses the short-sightedness of science, the Overreacher Plot criticizes science's will to knowledge. The Overreacher Plot has four basic movements. The first comprises the preparation for the experiment, generally including a philosophical, popular-mechanics explanation or debate about the experiment's motivation. The overreacher himself (usually Dr. Soandso) can become quite megalomaniacal here, a quality commented upon, for instance, by the dizzyingly vertical laboratory sets in Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein . Next comes the experiment itself, whose partial success allows for some more megalomania. But the experiment goes awry, leading to the destruction of innocent victims and/or to damage or threat to the experimenter or his loved ones. At this point, some overreachers renounce their blasphemy; the ones who don't are mad scientists. Finally, there is a confrontation with the monster, generally in the penultimate scene of the film.

The Overreacher Plot can be combined with the Discovery Plot by making the overreacher and/or his experiments the object of discovery and confirmation. This yields a plot with seven movements—onset, discovery, confirmation, preparation for the experiment, experimentation, untoward consequences, and confrontation.[*] But the basic Overreacher Plot differs thematically from

Confirmation as well as discovery may come after or between the next three movements in this structure.

the Discovery Plot insofar as the conflicts central to the Overreacher Plot reside in fantasies of omniscience, omnipotence, and control. The plot eventually cautions against these impulses but not until it gratifies them with partial success and a strong dose of theatrical panache.

In suggesting that the plot structures and fantastic beings of the horror film correlate with nightmares and repulsive materials, I do not mean to claim that horror films are nightmares. Structurally, horror films are far more rationally ordered than nightmares, even in extremely disjunctive and dreamlike experiments like Phantasm . Moreover, phenomenologically, horror film buffs do not believe that they are literally the victims of the mayhem they witness whereas a dreamer can quite often become a participant and a victim in his/her dream. We can and do seek out horror films for pleasure, while someone who looked forward to a nightmare would be a rare bird indeed. Nevertheless, there do seem to be enough thematic and symbolic correspondences between nightmare and horror to indicate the distant genesis of horror motifs in nightmare as well as significant similarities between the two phenomena. Granted, these motifs become highly stylized on the screen. Yet, for some, the horror film may release some part of the tensions that would otherwise erupt in nightmares. Perhaps we can say that horror film fans go to the movies (in the afternoon) perchance to sleep (at night).

Human Artifice and the Science Fiction Film

J. P. Telotte

The human artifice of the world separates human existence from all mere animal environment, but life itself is outside this artificial world, and through life man remains related to all other living organisms. For some time now, a great many scientific endeavors have been directed toward making life also "artificial," toward cutting the last tie through which even man belongs among the children of nature. . . . There is no reason to doubt our abilities to accomplish such an exchange, just as there is no reason to doubt our present ability to destroy all organic life on earth.

Hannah Arendt[1]

Vol. 36, no. 3 (Spring 1983): 44–51.

"I know I'm human," the protagonist of John Carpenter's film The Thing asserts, as he frantically searches for a threatening alien presence among his comrades. Taken out of context in this way, such a declaration sounds almost pointless, like an assurance of something that should be evident to the gaze of those around, as indeed it seems to the movie viewers. The very need for such an assertion, consequently, hints at an unexpected uncertainty here, even an uneasiness about one's identity and, more importantly, about what it is that makes one human. It is an uneasiness, moreover, which cannot be dispelled by a simple gaze, the means by which we typically evaluate our world, others, and ourselves. I call attention to the character McReady's predicament because it makes overt a specter which has continually haunted the science fiction film genre. Periodically throughout its history, but increasingly so in recent years, this formula has taken as its focus the problematic nature of the human being and the difficult task of being human. And as Hannah Arendt makes clear, the former concern seems to pose an ever greater barrier for the latter.

In this context, we should note the number of recent films which take as their major concern or as an important motif the potential doubling of the human body and thus the literal creation of a human artifice. Among others, films like the remakes of Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Thing, Blade Runner, Alien , and even Star Trek explore some aspect of this motif, but especially a welcome or threatening capacity which inheres in this cloning or copying of the self, cell for cell, and which promises to make man both more and less than he already is. Not simply a current development, though, this motif runs throughout the history of science fiction film. Viewed from the perspective of their "mad scientist" themes, the numerous Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde films represent paradigms of this tendency; in fact, the enduring confusion in the popular imagination that attributes the single name of Frankenstein to both a monster and its creator underscores the effect of this doubling pattern. One of its earliest and most characteristic treatments, however, occurs in a film that many see as

the prototype for the genre, Fritz Lang's Metropolis . The modeling of the heroine Maria into a destructive android look-alike serves as the narrative's centerpiece and prompts its greatest display of scientific gadgetry—that which we have come to expect to be the very core of the science fiction film. Visually indistinguishable from the real Maria, the android threatens to unleash dangerous desires in the human community and thus bring about disaster. Because she is both alluring and potentially destructive, the artificial Maria well represents the disturbing implications of that capacity for doubling and artifice which man's science has attained.

Probably the landmark treatment of this doubling motif occurs in the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers , which focuses precisely upon a threatening possibility for perfectly duplicating the human body, "cell for cell, atom for atom," as one character explains. In this case, it is an alien life form that uses nature wrongly, to grow seed pods which will deprive man of his own true nature, as they duplicate his body, "snatch" his intellect, but deprive him of all emotional capacity. While films had previously presented such duplication as a threat, the product of human aberrance or some misguided science, Invasion added a disconcerting note and also laid open a desire which has frequently moved just beneath the surface of these films, by pointing up a subtle attraction at the heart of the doubling process. The bloodless victory of the copy, of the pods, is actually lauded by those who have been subsumed into this emotionless community. This reaction suggests an elemental desire in man for the security and tranquillity which the sameness of duplication promises; as another character notes, this transformation permits man to be "born into an untroubled world" and to abdicate from the many problems of modern life—problems posed, it is implied, by the very advances of science, especially in the field of warfare, which, on the surface, usually seem a basic concern of these films.

Don Siegel, director of the original Invasion , admits that he sought to inject this challenge of attractiveness in response to a widespread desire he noted to abdicate from human responsibility in the face of an increasingly complex and confusing modern world. To this end he

purposely had the prime spokesman for the pods be a pod psychiatrist. He speaks with authority, knowledge. He really believes that being a pod is preferable to being a frail, frightened human who cares. He has a strong case for being a pod. How marvelous it would be if you were a cow and all you had to do is munch a little grass and not worry about life, death and pain. There's a strong case for being a pod.[2]

It is this "strong case" that has been repeatedly and increasingly stated in films since the time of Invasion. The Stepford Wives , for instance, plays not just upon the threat of a gradual, insidious replacement of the women in a small town by

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

mindless, dispassionate androids—apparently the perfect housewife—but also on the terror implicit in their similarity to what is held up as a cultural ideal and in the fact that this duplication is obviously desirable to those closest to the women, their own husbands. Perhaps because of our increasing concern with the potential for cloning and genetic research, such possibilities no longer seem so far-fetched, hence the recent spate of films exploring this complex proposition. They all emphasize man's fascination with knowledge and science, as has always been typical of the genre, but they link a single-minded pursuit of knowledge with that disconcerting desire to duplicate the self—or unleash the unknown power of duplication, as in The Thing —and its consequent rendering of the self almost irrelevant. In sum, they suggest how the human penchant for artifice—that is, for analyzing, understanding, and synthesizing all things, even man himself—seems to promise a reduction of man to no more than artifice.

This paradox also sheds some light on a subtle distinction which the science fiction film has typically sought to make in its depiction of man's attitudes towards science. As critics have frequently noted, the genre often seems to juxtapose a good and a bad science, white and black magic, as it were, with the one working to serve man and the other to threaten his position in the world. We might recall the novel Frankenstein 's subtitle, The Modern Prometheus , for it can help us to discern an even more telling distinction at work in the film genre. In its recurring manifestations, the doubling motif denotes a Faustian drive for knowledge or power, a dangerous and even self-destructive impulse behind that fascination with the power of science or some select knowledge to enable man to duplicate himself artificially. This Faustian impulse, however, typically tries to go masked as a Promethean one, that is, as a desire to bestow

significant boons upon man. Of course, it is in the nature of those boons—not light but likeness, and not the potential of fire but its destructive force—that we eventually perceive the Faustian persona beneath the Promethean seeming that science and the scientist usually bear in the genre.

Why this seeming, however, and why should its ultimate expression take the very shape of seeming, namely the doubling or copying of the self? The persistence of this theme hints at a certain hubris of the mind with which the genre is concerned: a pride in a science which is seen as seeking to accommodate all things to the self, ultimately even the self, which, because of a lingering Cartesian dualism between the mind and body, thinking and feeling, has become associated with both the internal life of the mind and an external world of otherness, the not-mind.[3] The fashioning of other bodies, other forms of the self, only reinforces that split between mind and body and reasserts the hegemony of the former over the latter. What I would like to suggest, following Arendt's lead, then, is that we might see in this doubling motif the indication of a science turned inside out, a drive for knowledge and control become a desire for oblivion, although it is a blind desire, as the self unwittingly turns upon itself, even while apparently engaged in a process of valorizing the self through the ability for replication.

The full paradox and threat inherent in this artificing of life lurks just beneath the surface of a film like Alien . In fact, the film's central horror, a monstrous presence that thrives on man, yet is apparently invulnerable to his normal defenses, seems metaphoric of some flaw within man, perhaps the Faustian drive that increasingly seeks expression. The murderous alien is brought into the spaceship because the company sponsoring the flight has established a primary directive for the crew to gather any information on life forms that might prove valuable. Arguing for this directive, and thus directly precipitating the alien's murderous rampage among the crew, is an android, a replica of man so perfect that he fools his fellow crew members. A perfect example of the danger behind this doubling pattern, he has been programmed to ensure the mission's knowledge-gathering activities, regardless of any danger which might accrue to the human component of the expedition. In the film's most startling scene, the alien creature that has embedded itself within one of the crew members suddenly bursts through his chest, killing the human host. Born from within man, this creature metaphorically embodies the monstrous potential of the double which has made its life possible. In short, the alien represents the displaced terror and true frightening aspect of that desire for knowledge which, also arising from within man, has begun to produce life-threatening doubles. It is only through this perspective of displacement that the complex plotting of Alien , and especially the discomfiting relationship between android and monster, comes into proper focus. In his discussion of the nature of man's proclivity for doubles, René Girard predicts just such a link and connects the desire for doubling to

man's most violent impulses; as he notes, there is "no double who does not yield a monstrous aspect upon close scrutiny."[4]

The new version of The Thing specifically emphasizes this "close scrutiny," that is, the visual problem posed by the double. When a scientific research team stumbles upon and accidentally unthaws an alien creature embedded in the polar ice for thousands of years, they unleash not simply a monstrous creature, one that threatens those discoverers, but a figure that seems to summarize the problems of doubling located in both Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Alien . As one character notes, this creature "wants to hide inside an imitation" and it possesses the power to "shape its own cells to imitate" any other being in its environment. That this capacity for perfect mimesis is not simply a protective mechanism, like a chameleon's color adaptation, but a very real threat to man is underscored by the gruesome scenes of possession and transformation for which the film has been scored on occasion. In fact, The Thing seems to draw on Alien 's "chest-buster" sequence as a model for these scenes—a connection which underscores the importance I have here attached to that previous scene and one which hints at an internal component in this alien doubling. What The Thing particularly adds to the previous formulations of this doubling motif is an emphasis on the contagiousness of this tendency, and thus its more than individual menace. As the doctor among the group calculates, at its current rate of assimilation of man, the alien polymorph could take over all of humanity in "27,000 hours from first contact." It thereby threatens rapidly to reduce man's world to a realm of imitations, to make everyone simply an extension of that alien presence.

With the awareness of this threatening possibility, an equally devastating potential also emerges, one which inheres in every act of doubling. Because man is possessed of an absolute desire for certainty or knowledge—at least, so the science fiction genre argues through its emphasis on the compulsion for knowledge—he can easily become prey to an almost debilitating anxiety in the face of whatever stubbornly resists his attempts at formulation. And when the enigma is his own double or potential double, the anxiety may take even deeper root. Almost frantically, therefore, the men at this isolated outpost reach out for some answer, some assurance, even "some kind of test," as one of them puts it, which might detect this alien presence in their midst and thus assure them that they are all just what they appear to be, truly men. Significantly, however, this task of detection and inquiry into the visible world quickly transforms into a suspicion of the human society in which they are immersed, even an uneasiness about the self; as one man asks, "How do we know who's human?" It is a question that betrays a deep-seated fear, normally kept hidden yet essentially commonplace, of all that is not the self. Calling attention to this rapid breakdown of human society which the alien visitation has precipitated, McReady notes

that "Nobody trusts anybody now." What such a comment also bears witness to is an alien potential which resides in man, ever ready to be triggered by circumstance and to raise a disturbing suspicion not only about one's fellow man, but even about the self and its relationship to that human world it must inhabit.

What The Thing locates, therefore, is a certain thing -ness within man, an absence or potential abdication from the human world which can only be made present or visualized in the mirror furnished by the doubling process. The confrontation with which the film ends, as McReady and a black man, the only other survivor of the group, eye each other suspiciously, each equally sure that the other is only a double fashioned by the alien, metaphorically points up the distrust and fear which already typically mark modern society, and particularly its race relations. Of course, the doubling process which the alien initiated promised to render everyone the same, each an extension of that single intruder, and in their mutual fear of the other McReady and his comrade have already fulfilled that promise after a fashion. Moreover, that threat precipitates with both men a retreat into the private space of the mind, the one stable ground upon which they feel they can still stand. In effect, the mind is thus seen as the true repository of the self, protectively questioning all about, while asserting with ever decreasing conviction one's own humanity, as we have already seen McReady doing. If that phrase, "I know I'm human," seems to ring hollow, it is because the narrative, through its visitation of this disconcerting doubling, has managed to undercut all certainty, all dependable knowledge, certainly all reliance on appearance. Consequently, at the film's conclusion even we are unsure if one or neither of the survivors is indeed a copy, just waiting his chance to spread his mimetic reign into the outside world. Indeed, we are left to question the very future of man's life on earth, just as Arendt does.

In another sort of investigation into the nature of our modern culture, Loren Eisely has attempted to trace out the process by which "man becomes natural," that is, how he came to see himself as a part of nature and its historical processes, rather than as a strange occurrence and an intrusion into the natural world. "Before life could be viewed as in any way natural," he explains, "a rational explanation of change through the ages" was needed;[5] man had to acquire a thorough knowledge of the patterns of evolution. The recent film Blade Runner dramatizes the logical consequences of this mastery of evolutionary principles. The development of this understanding, the film suggests, serves as the springboard for the current concern with the possibilities of genetic engineering, which, in its turn, has generated a potential for scientifically controlled evolution: the creation and programming of perfect replicas of man, gifted with unusual beauty, strength, or intelligence, and made to serve their human creators. As a result of this original step in "becoming natural," however, apparently something has also been

lost. As Eisely points out, while "man has, in scientific terms, become natural . . . the nature of his 'naturalness' escapes him. Perhaps his human freedom has left him the difficult choice of determining what it is in his nature to be."[6] The problematic nature of human nature is precisely the topic on which Blade Runner with its formulation of the doubling motif attempts to shed some light.

As in The Thing , a sense of uncertainty and the anxiety which attends it seem to color the very world of Blade Runner and to derive in large part from the fascination with doubling which it chronicles. The futuristic environment the film describes seems perpetually dark and rainy, as gloomy as that of film noir—the conventions of which Blade Runner does in fact draw on. In this bleak atmosphere we can see mirrored an interior darkness that afflicts the characters here and seems brought on by the problems arising from a culture practically predicated upon the possibilities of duplication. In this future world, man has progressed to such a point that he can genetically design and reproduce virtually anything that lives; thus we see mechanical birds, snakes, dogs, and especially people—or "replicants," as they are here termed—all of which are virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. They have been fashioned by man's science in order to satisfy his various desires, to free him from labor and the dangers of combat, or simply to amuse him. And yet in spite of these benefits, no one seems truly happy in this society; in fact, those who can do so readily abandon this world in favor of one of the "off-world colonies," doubles of the earth itself which, like so many of the copies here, are apparently perceived as being better than their original. We thus see a vision of man not only no longer at home with himself, but no longer at home with his home; and the human doubles promise to increase the level of anxiety by refusing to remain in their servile roles and demanding instead a life like that of their creators and models.

As is typically the case in the science fiction genre, then, a kind of monstrous creation has transpired, but it has gone masked as scientific advance. In the place of Frankenstein are two geneticists—Dr. Tyrell, master designer of replicants, and J. F. Sebastian, his chief genetic engineer. Both appear to have given that Promethean impulse free reign, pushing the desire to fashion a copy of man to its extreme in their specially designed androids for every task and every distraction. The ostensible project of providing for human needs, however, has clearly been submerged by a pride in the process of doubling itself. Tyrell, it seems, is moved solely by his fascination with creating ever more perfect copies, replicants which can defy those tests for humanity which have developed in this future world—just as The Thing predicts. And with the girl Rachael, whom he addresses at one point as "my child," he has nearly succeeded. Sebastian has turned his engineering skills to no less subjective end, the task of filling his lonely life with manufactured "friends," albeit small, misshapen, flawed figures—apparently various reflections of his own flawed body, which suffers from "premature

decrepitude." In sum, these scientists have turned their capacities for creating copies to their own ends, and in the process have endowed their creations with a certain reflexive capacity, Tyrell's figures mirroring his own desire for perfection, beauty, and transcendence of mechanical limitation, Sebastian's reflecting not only his own defects, but also his flawed view of himself.

In these projections of the self, moreover, both have already created the conditions that must eventually render them irrelevant. Because they have programmed their replicant creations with memories of a life that never was—even providing them with photographs of supposed relations and friends—and thus tried to convince them of their humanity, these engineers have erected a potentially dangerous bridge between the human and android realms. In fact, they have succeeded too well, for they have unleashed a synthetic but powerful desire for real life, one which—as is the case in films like Frankenstein, Invasion of the Body Snatchers , and The Thing —initially places itself in opposition to the possessors of normal life, mankind. In attempting to return to Earth from the off-world colonies, the group of replicants with whom the narrative is concerned have already killed 23 humans; and after finding their way back, they predictably turn their attention to their creators, particularly Tyrell and Sebastian. What they quest for is the secret of their programmed lives, and particularly, after the fashion of men through the ages, the means to a longer life. In effect, they have embarked on a Promethean search of sorts, seeking the archetypal fire of life itself, but in that murderous trail they leave behind, we see the clearest signs of that violence which, as René Girard has noted, usually goes masked by the doubling process.[7]

An even more telling measure of the ambiguity which attaches to this doubling process is found in the absence of a sure anchor for our own sympathies in this situation. That is, in the absence of the more typical monstrous presence and as a natural outgrowth of the desire for a nearly perfect mimesis which has produced these doubles, our concern shifts uneasily about between the world-weary, alienated bounty hunter Rick Deckard and those replicants whom it is his task to hunt down and destroy. Another and equally compelling reason for these shifting sympathies, of course, is that, as we quickly recognize, both man and android here essentially share the same—a doubled—fate. Like Sebastian, the replicants suffer from their own form of premature decrepitude, a programmed mortality which ensures their inevitable death after four years of service. As a consequence, these androids face the same sort of disconcerting knowledge that man has always had to abide with, that of an inescapable and onrushing death. Fed up with his work as a bounty killer, meanwhile, Deckard meditates on the nature of his quarry and, in turn, begins to wonder about his own place in this confusing welter of being wherein everything, perhaps even himself, seems to have its double or be itself a copy. Thus

The replicant Rachael in Blade Runner

he comments at one point, "Replicants weren't supposed to have feelings; neither were blade runners" like himself. It is a complex mirroring pattern which has resulted from the doubling process, as men and androids begin to see themselves in each other and, discomfitingly, prod the others into a questioning of their very nature.

In the character of Rachael, Tyrell's nearly perfect replicant, this increasingly blurred distinction between man and the copies with which he has become obsessed finds its clearest example. Accepting the testimony of his own experienced eye, Deckard is initially fooled into believing her human, and he finds himself mysteriously attracted to her. What is more unsettling is that his fascination continues even after he administers the Voight-Kampff Empathy Test, which reveals that she is a replicant. The precise meaning of those test results quickly seems to evaporate in light of Rachael's manifest "humanity," however: her love of music, desire for affection, concern for others, and apparently a love for Deckard. Her response to the test's conclusions, asking Deckard, "Did you ever take that test yourself?" only compounds his quandary; it causes him to

reflect on his own humanity, on the nature, that is, of a hired killer. As a result of this reflection, the subsequent order to kill Rachael along with the other replicants prompts a marked shift in the blade runner's attitude, a questioning of that which usually goes unquestioned, namely the humanity of those who create—and destroy—these artificial lives. He thus refuses the order and instead runs off with her to spend whatever little time her short, engineered life leaves them together in a different world, as a last shot indicates, a realm of light, greenery, and life, rather than the dark, rainy cityscape which has produced them both. In effect, Deckard takes Arendt's warning to heart, abandoning "the human artifice of the world" in favor of a natural environment in which man might regain his truly human nature.

If it seems ironic that a replicant or double should provide the stimulus for such an awakening to the self and a proper sense of humanity, it may be a telling indication of how far modern man has come in his fascination with artifice and how much he has lost in exchange for that knowledge of how to double the self. No longer viewed simply as the abnormal desire of aberrant types, as in the numerous films which have focused on mad scientist types, doubling has here become the very hallmark of society, something its members take for granted—but like many things we take for granted, it is also a pernicious influence. As Blade Runner suggests, when this abiding fascination with doubling becomes a dominant force in man's life, he clearly runs the risk of becoming little more than a copy himself, potentially less human than the very images he has fashioned in his likeness. Man's scientific advances, in sum, threaten to render him largely irrelevant, save as an empty pattern within which knowledge might be stored and through which it might extend its grasp, further increase its capacities, and expand the realm of artifice.

At another level we should find it most fitting that a double should spur an awakening to a sense of self. In essence, another form of the doppelgänger archetype, the replicant might be expected to serve the sort of salutary function that other archetypal patterns do. In explaining the effect of archetypal images on the psyche, psychologist James Hillman notes that "reversion through likeness, resemblance," affords the mind "a bridge . . . a method which connects an event to its image, a psychic process to its myth, a suffering of the soul to the imaginal mystery expressed therein."[8] In such "resemblance," he claims, there is located a path to a psychic truth which we have forgotten or lost sight of amid the welter of modern-day experience. Because of its reflective dimension, then, the image of the double, android, replicant, or copy holds out a great promise, even as it seems rather threatening, for it carries the potential of bringing us back to ourselves, making us at home with the self and the natural world almost in spite of ourselves. We might view the combat between Deckard and the android Roy Batty in exactly this context. In the middle of their fight, Deckard slips from the

top of a building and dangles precariously in the air; only the outstretched hand of Batty, grabbing Deckard at the last moment, stops his fall and brings him back from the brink of death to a possible life. It is precisely the sort of saving potential or "reversion" which always inheres in the image of the double and which may ultimately best explain the continuing fascination it holds for us.

In attempting to map out the large territory of fantasy narratives, Tzvetan Todorov identifies a singular tension at work in the form which reflects the fundamental experience of its audience. Both reader (or viewer) and protagonist, he asserts, "must decide if a certain event or phenomenon belongs to reality or to imagination, that is, must determine whether or not it is real. It is therefore the category of the real which has furnished a basis for our definition."[9] As a result of this indeterminacy, we experience "a certain hesitation" as we try to "place" the events of the narrative within a known field of personal experience or reservoir of knowledge, just as the story's characters do. In this moment of hesitation, we should be able to discern the problem of representation which lies at the genre's very core, for we hesitate because of an immediate challenge to our usual system of referents, the stock of images which lived experience normally affords. At the same time, of course, that hesitation achieves a valuable purpose in prompting this stock-taking and thus starting a most subtle reflective experience.

In its recurrent concern with a doubling motif, the science fiction film thus draws on one of the fantastic's deepest structural patterns. In those images which fall outside of our normal lexicon, the film genre admits to a mystery or enigma that is at its center; and in bracketing the image of man—through those copies or replicants—within this enigmatic category, it admits of a puzzle to which we too are a part. Even as it limns the progress or potential of science, reason, and knowledge, therefore, the genre also acknowledges an underlying mystery and ambiguity, certainly in the approximations with which our mimetic impulse has always had to content itself. The fact that these disconcerting copies are in our own shape reminds us how little science has yet learned of substance about man, how little, in essence, we know about the most alluring of models for mimesis. As Arendt noted—and as our accomplishments in genetic engineering every day point up—we already possess the potential which science fiction films have so frequently described, that for crafting artificial versions of man. What these films hope to forestall is the dark obverse of this capacity, that for making human nature artificial as well.

Confessions of a Feminist Porn Watcher

Scott MacDonald

Finally, here's a proper subject for the legions of feminist men: let them undertake the analysis that can tell us why men like porn (not, piously, why this or that exceptional man does not), why stroke books work, how oedipal formations feed the drive, and how any of it can be changed. Would that the film [Not a Love Story] had included any information from average customers, instead of stressing always the exceptional figure (Linda Lee herself, Suze Randall, etc.). And the antiporn campaigners might begin to formulate what routes could be more effective than marching outside a porn emporium.

B. Ruby Rich, "Anti-Porn: Soft Issue, Hard World,"

Village Voice, July 20, 1982

Pepe Le Pew was everything I wanted to be romantically. Not only was he quite sure of himself but it never occurred to him that anything was wrong with him. I always felt that there must be great areas of me that were repugnant to girls, and Pepe was quite the opposite of that.

Chuck Jones, "Chuck Jones Interviewed," by Joe Adamson,

The American Animated Cartoon, Ed. Danny and

Gerald Peary (New York: Dutton, 1980), 130

Vol. 36, no. 3 (Spring 1983): 10–17.

For a long time I've been ambivalent about pornography. Off and on since early adolescence I've visited porn shops and theaters, grateful—albeit a little sheepishly—for their existence; and like many men, I would guess, I've often felt protective of pornography, at least in the more standard varieties.[1] (I know nothing at all about the child porn trade which, judging from news articles, is flourishing: I've never seen a child in an arcade film or videotape or in a film in a porn moviehouse; and though I've heard that many porn films involve women being tortured, I don't remember ever coming in contact with such material, except in Bonnie Klein's Not a Love Story , a film polemic/documentary on the nature and impact of porn films.) On the other hand, I've long felt and, in a small way, been supportive of the struggle for equality and self-determination for women; as a result, the consistent concern of feminist women about the exploitation and brutalization of the female in pornography has gnawed at my conscience. The frequent contempt of intelligent people for those who "need" pornographic materials has always functioned to keep me quiet about my real feelings, but a screening of Not a Love Story and a series of recent responses to it—most notably the B. Ruby Rich review quoted above—have emboldened me to assess my attitudes.

As I watched Not a Love Story , the film's fundamental assumption seemed very familiar: pornography is a reflection of a male-dominated culture in which women's bodies are exploited for the purpose of providing pleasure to males by dramatizing sexual fantasies which themselves imply a reconfirmation of male dominance. And while one part of my mind accepted this seemingly self-evident assumption, at a deeper level I felt resistant. The pornographic films and videotapes I've seen at theaters and in arcades are full of narratives in which women not only do what men want and allow men to do what they want, but effusively claim to love this particular sexual balance of power. Yet, given that males dominate in the culture, why would they pay to see sexual fantasies of male domination? Wouldn't one expect fantasy material to reveal the opposite of the status

quo? Further, if going to porn films or arcades were emblematic of male power, one might expect that the experience would be characterized by an easy confidence reflective of macho security.