3—

If Looks Could Kill

. . . Can it be that everybody is looking for a way to fit in? If so, doesn't that imply that nobody fits?

Perhaps it is not possible to fit into American Life. American Life is a billboard; individual life in the U.S. includes something nameless that takes place in the weeds behind it.

—Harold Rosenberg

I

Mommy was away at Payne Whitney, a hospital in New York City, for the better part of a year, from the fall of 1953 through the summer of 1954. She went there after she had a nervous breakdown toward the end of summer, sometime after we drove back to Alabama from Indian and Forest Acres; she said she needed to get away from the house and four boys and Stanley for a while, and Bo offered to pay for Payne Whitney, where she hoped to get better.

None of us can recall with any clarity her leaving, only being told that she was gone, although Alvin today remembers an argument he had with Daddy at Bo and Grandma's one Friday night shortly afterward. Alvin wanted to know how he could be sure that anything was true when all he had to go on was what grownups told him. For instance, if he was passing by the City Drug (on the corner of Seminary and Tennessee, where Daddy took us all for lunch on Saturdays), how did he know it was called the City Drug, apart from grownups telling him that? And what about Mommy—how did he know she wasn't dead, that she really was away in New York like Daddy and Bo said she was?

Mommy felt well enough to come back in late November for her fifteenth wedding anniversary. A few weeks after that Daddy flew up to New York to discuss an adjustment of rates with Payne Whitney so that he could take over the expenses from Bo. The doctors wanted her to stay there longer and longer, but they let her come home for more visits: in April and May, for David's bar mitzvah, and then again in September.

We fixed up an elaborate party for her when she arrived in September, both at the house and over at Bo and Grandma's on North Wood Avenue, with dozens of posters and crepe paper streamers and little pieces of paper that said "Welcome Home Mommy" positioned everywhere from the front carport to the master bedroom; Jonny even slipped an extra one inside the refrigerator. We were all hoping to convince her to stay home this time, despite what her doctors said, and our plan worked: she called the hospital and told them she wasn't coming back. (The following year, on her doctors' advice, she went to see a psychotherapist once a week in Birmingham.)

We all carried on long-distance love affairs with her when she was away. Each was carried on in a different manner, in a different language.

Every day, in his office, Stanley typed her a letter on Muscle Shoals Theatres stationery.

Alvin was learning to play the violin. Mimi loved music; she had studied at Greenwich House Music School in the thirties and sometimes played Brahms, Chopin, and Beethoven on the grand piano in our living room. When Alvin saw Rhapsody at the Shoals with Mommy and Daddy on the last Sunday in April ("Three-cornered romance among rich [Elizabeth] Taylor, violinist [Vittorio] Gassman, and pianist [John] Ericson: melodic interludes bolster soaper," notes Leonard Maltin in TV Movies, assigning it two and a half stars), he resolved to become a violinist by the time she came home again, and he eventually convinced Daddy to let him start taking private lessons.

David, in seventh grade at Florence Junior High (a rougher, lower-class place than Kilby Training School), wrote Mommy about winning first place in the magazine subscription sales contest sponsored by Curtis Publications.

Jonny drew comics and family newspapers with crayons and colored pencils (including a couple in 3-D, requiring cardboard glasses with cellophane lenses) and wrote poems, stories, letters, and postcards, all of which he sent to Mommy.

When Michael learned to write out his whole name on a piece of paper—his first name without even copying it—Jonny sent that along, too.

On Tuesday, January 12, 1 p.M., during his free period in school, Jonny wrote Mommy about the marionette he was making, his plans for the afternoon (a haircut, then Easy to Love at the Shoals), the snow that had fallen the day before, a book of mysteries he'd checked out of the Kilby library, and other diverse matters:

Last night, on surprize night, David Darby spent the night with us. Daddy read to us: [John Collier's] "another American Tragady," "Lamb's version of 'A Winter's Tale,'" and a couple of chapters from "Miss Minerva's Baby.

"I've been trying to keep my hair the style you showed me before you left. David R. has been playing basket ball every day for the last week or two.

Mommy/Mimi wrote back to all of us, individually and collectively. When Alvin and Michael went with Bo and Grandma to Miami—thereby entitling

David and Jonny to go along with Daddy on his trips to New Orleans and Atlanta, respectively—she sent a giant-size postcard of the United Nations to David, Jonny, and Stanley (" . . . Forgot to tell you I saw 'From Here to Eternity' several wks. ago too—but not one of my first choices as you say. Hope you 3 men are holding down the fort. Waiting to hear from Florida. Love, Mommy & Mimi"). A few weeks earlier she had sent Jonny a postcard showing a clump of big buildings, with labels, arrows, and a little circle added in her blue fountain pen ink to indicate Cornell Medical College, New York Hospital, Payne Whitney, and her room in the latter. (Her P.S. on the other side: "Just got the 'Rosenbaum Times.' It's a wonderful issue. You get better all the time. Did you give away the puppies yet?")

Sometime in August she sent this letter:

Tuesday

Jonny darling,

I loved reading your last 2 publications & so did my friends. I even gave it to Mr. Hodgins to read. He's the man who wrote "Mr. Blandings builds his dream house." He enjoyed them very much. I'd love to have more whenever you feel like it—

You'd better brush up on your scrabble because when I come home, I'm going to play with you. I'm a fairly good player—I'm warning you!

I guess daddy told you I'm just starting to go out again—I've been doing it gradually. Since I started I saw 2 movies: "On the Waterfront" with Marlon Brando—It was a very intense & forceful picture all about the Stevedores' union—It was actually filmed in Hoboken, N.J. & was very realistic. There's a Catholic priest in it who does as good a job of acting as Marlon Brando, I think. I don't think it's your style—but whenever you/we get it at home—don't fail to see it—you'll learn a lot about what goes on—for real . The other picture was "Seven Brides for Seven Brothers"—at Radio City—in Cinemascope. It was very gay & entertaining—full of spirit—the dancing and singing—very good. Somehow, it reminded me of "Oklahoma"—the outdoorishness of it—the freshness. I don't think you saw "Oklahoma" in N.Y. though, did you? I'd like to see "Rear Window" now—an Alfred Hitchcock production—which I hear is wonderful. I guess I will, when I go out this week. "Dial M for Murder," another Hitchcock picture is one I don't want to miss either. Daddy writes we're having that at home, too.

I hear also that you gained 3 lbs. Wonderful! What are your favorite foods these days? Have you seen Alan Stein again recently? I know he's lots of fun to be with. Daddy writes me that you see Lannes occasionally too. David D. is in California I hear. Do you hear from him?

I guess you heard that I Am Coming Home For A Visit In September! I can hardly wait myself. The doctors can't tell me yet just when in September it will be—but I do have an idea it will be for about a week or 10 days—thereabouts. It can't come soon enough for me!

Be sweet Jonny darling & write me—Big—big hugs & kisses—

Love—

Mommy

Saturday, December 2, 1978

Dear Mimi,

I realize that it's strange to be writing you this way, within the context of a book, and I'm trying to explain to myself, first, why this method of addressing you allows me more freedom than an ordinary letter or conversation would. I think it has a lot to do with the degree to which both our lives and our communications with each other are so firmly bound up in habits that sometimes it's hard to reach beyond them. I guess that's what I'm trying to do here, and if I'm choosing to do this in a relatively public place, I can assure you that it isn't intended to embarrass you. You will read this letter before any stranger does, and I'm offering you "exclusive" cutting rights; that is, nothing will go into this book that you seriously object to. On the other hand, assuming that you don't object, I can't guarantee that this letter will appear in the book. That will be for the book to decide, in terms of how it develops; and at this point I can't even be certain how this letter is going to develop. (Nor can I be sure that the book will be published—I'm still awaiting word from Cynthia Merman, the editor I know at Harper & Row.) Whatever happens, I hope to resolve at least one question that deeply concerns me: whether or not it is humanly and ethically possible to address one's mother and one's reading public at the same time without betraying or alienating either. I'd like to think that it is, but I can't be sure because I've never tried it.

What triggered this letter was another letter, written to me nearly twenty-five years ago. Do you remember my few minutes of rummaging through the closet in the back bedroom, my old room that you use now for weaving, before you drove me to the bus station on Wednesday? I grabbed some letters from one of the boxes of my things—I can't imagine how I missed them on my two previous trips—and slipped them into my briefcase, to read on the bus to Nashville. Now that I think of it, I can imagine why I hadn't taken those letters back in August 1977 or March 1978: I hadn't yet begun to focus on this part of the book, dealing with the period you spent at Payne Whitney. I was working on my first two chapters then, both of them fundamentally tied up with the patriarchal axis of God, Dad, Bo, and Rosenbaum Theatres—not to mention the Conquistador—which prevented me from broaching the realm of you and the house, and the relevance that had to those same experiences.

After our rushed trip to the bus station, when both of us were too nervous to express a proper goodbye, I had a wonderful stroke of luck: your letter of 1954 was the first letter I pulled out of my briefcase, the first one I read on the bus. As soon as I started it, I felt an intense desire to copy it out word for word, and a few minutes later I did precisely that, in the process becoming you composing the letter and at the same time myself, at eleven, receiving it. Today, when our geographical positions are reversed—I'm in New York and you are in Florence—and I'm about the same age now that you were then, I feel that I must write you back in gratitude a second time. If Michael and I

didn't get up to speak at your and Stanley's fortieth anniversary get-together last week, as Alvin and David did, I'm sure you realize that it was because we need different styles, moods, and climates in order to express these things. Michael, taking after Grandma, did it largely through his cooking, which he managed to combine with his own philosophy of continuity by calling his specialty "Dead Grandma's Strudel." My way, I hope, is evident in the pages of this book.

It's now early February. Eleven days after I began this letter I flew to Berkeley for three weeks. Eight days after I arrived Sandy woke me on her way to work to hand me the phone, and Cynthia at Harper & Row told me they had just agreed to publish this book. I hope to be signing the contract in two days. Tomorrow my "Rivette in Context" season starts at the Bleecker Street Cinema; it has already had two lengthy write-ups (by Andrew Sarris and Roger Greenspun) that will certainly help it to do well, even though both critics are dubious about Rivette.

Four days ago, I made a pilgrimage of sorts to Payne Whitney on East 68th Street, where I had never been before. I stood opposite the building complex with your old postcard and traced the windows with my eyes until I found the circled one, the room that had been yours; then I tried to imagine what a reverse angle from that room would be like—the view you had of the park and the surrounding buildings in the winter of 1953–1954 (was it as cold as this one?). I realize that it's folly to attempt such an exercise, futile even to imagine that it could lead to something meaningful. For a reverse angle now wouldn't be the same as a reverse angle then; and if it were, what could such an image possibly give me other than the assertion of a kind of knowledge that I couldn't possibly have—the same sort of cover-up to our general ignorance about things that movies habitually trade on? But I have to start somewhere, even if that somewhere is false.

Anyway, it's the movies that remain, not the places; not the time you spent at Payne Whitney, which I'll never know much about, but the movies that pass like air ducts between me and parts of that experience—passed to me through your letters, giving them an identity even before I saw them. When I actually breathed them later (Dial M For Murder in August, Seven Brides For Seven Brothers in October, On The Waterfront in January, Rear Window in February), you were the leading character for me in each one. You were not only Grace Kelly (whom you resembled) in the two Hitchcocks, but also Jane Powell in Seven Brides , and Eva Marie Saint in Waterfront . My glamorous view of you, which already made you a movie star, was largely what these movies were about.

Two hours past my thirty-sixth birthday and five days after I stopped smoking (which tends to make me more impatient than usual about a lot of things)

I'm remembering our phone conversation around Christmas. You and Stanley had read the preceding chapter; he compared it to three-dimensional chess, and you described it as a form of psychoanalysis that I don't get charged for. You're both right, and it occurs to me now that both of you named activities that can be made to drag on indefinitely, if necessary. Yesterday your newsy letter arrived (with the $20 birthday check from you and Stanley—many thanks), reminding me, to my embarrassment, that I started this letter nearly three months ago!

Jane Powell in Seven Brides and Eva Marie Saint in Waterfront were like you and me at the same time, frail vessels bearing morality and sensitivity in a brutal macho world—even if other bits of me went to Brando, Keel, and Russ Tamblyn in those movies. Like Eva Marie, you were a New Yorker from a working-class family and neighborhood; like Jane, you were a gal from the city who married a country boy and eventually found yourself planted in a family of male despots (six in all, including Bo, against Jane's seven). "Bless your beautiful hide," sang Howard Keel robustly, before he even met you.

Grace Kelly, however, was you and you alone in the two Hitchcocks, hence more mysterious. In Dial M for Murder this wasn't merely a matter of my linking her sewing basket and scissors with yours (Freudians, please note); it also involved the "convenient" way in which she was whisked offstage for a long stretch of the action so that the male characters could take charge of all the important business (the planning of her murder and the subsequent crime detection) without unnecessary kibbitzing on her part. Which is another way of saying that, as you were the most silent member of the family in those days, your victimization was a lot like hers.

Yet Rear Window was your apotheosis, for Grace was a sophisticated New York model in that movie, just as you were a Powers model when this picture was taken. When Grace modeled a Mark Cross travel bag—a plug for a product slyly integrated into the plot; the modeling performed for her immobilized boyfriend, James Stewart, when she comes to spend the night—seeing her was like seeing you in that Chesterfield ad on the back cover of Life . The image of suave, practical-minded but stylish Grace showing James what a shrewd consumer she is seems as crystal-clear in my mind's eye as Vista Vision itself, the deep-focus process in which the movie was made. (Lucky me, I'd seen an advance demonstration of it with Stanley, at an exhibitors' convention in Atlanta the previous spring.) Crystal-cool, too, unlike the more frigid remoteness of 3-D or the warm, indiscriminate expanses of CinemaScope; as crystal-cool-clear as my first pair of glasses, so that when either you or Stanley drove me home from the clinic, past the suddenly crisp snow-covered visage of downtown Florence, along the darkening dips and curves of Riverview Drive at dusk (the houses, lawns, and fences more firmly outlined now, more set apart), and into the snug glow of our house's radiant

Mildred Bookholtz, 1935

heating (which promptly fogged up my lenses), all I could think was, Vista-Vision, my God—wearing glasses was just like Vista Vision.

3-D was a lot less real than that. It was generally agreed—by David Darby, Lannes Foy, and me, among others—that Fort Ti had the best effects: burning arrows and squirts of tobacco juice, both projected straight at the audience. A more typical specimen would be some godforsaken nullity like Second Chance —seen successively at the Princess in Florence on October 18, 1953, and at the Thalia in New York on February 23, 1979, the day I stopped smoking—a movie whose principal (unwitting) achievement was and is to flaunt its own artifices rather than to enhance any illusion of reality. Thanks to 3-D, the painted backdrops and grainy rear projections looked even flatter and the reverse angles tended to look phonier by denying the spaces that had been occupied, in the previous shots, by the camera itself. The renegotiation and redistribution of pockets of deep and shallow space that occurred with each cut, each change of camera position, made the question of point of view seem arbitrary and contrived and each camera angle as isolated from the preceding one as a separate View Master square. With the illusion of depth ready to collapse the moment you tilted your head, how long could anyone suspend disbelief?

Because of this lunacy, the Technicolor comic-strip bodies and physiognomies of the stars, projected into a freakish depth, became as shapeless as dialogue balloons: Robert Mitchum, a Joe Palooka languishing like a sea slug inside a zoot suit; Linda Darnell, whose breasts, boldly cantilevered in the usual Howard Hughes/RKO manner, tended to dwarf all her other human attributes; Jack Palance, whose craggy, elegant profile seemed to belong on the head of a penny. Maybe, in the final analysis, it was all a matter of budgets and production values. 3-D failed because it didn't become identified with money, religion, or culture—unlike CinemaScope and stereophonic sound, which started off with the The Robe and How to Marry a Millionaire , the latter introduced by nothing less than curtains parting and Alfred Newman's symphonic orchestra playing a dull "Street Scene" overture for more than half a reel from inside an amphitheater in the clouds.

It was certainly easy for me to identify with James Stewart in Rear Window . As many critics have noted, his position in the movie is like that of a film spectator—immobilized by a broken leg and watching through the window the real or potential couples in the apartments across the court, meanwhile evading the countless appeals and demands of Grace. So when he suspects that the neighbor opposite him has murdered his wife, sends Grace to search for evidence, and then watches helplessly as the guy returns and catches her, the guilt-ridden suspense of that moment—compounded by the spatial simultaneity and God's-eye view afforded by the depth of Vista Vision, the creepy neighbor approaching in the hallway while Grace lingers unknowingly inside the apartment—was almost unbearable. ("It's Perry Mason!" de-

clared Connie Greenbaum in a thrilled whisper, and giggled, at the Paris Cinémathèque, August 21, 1972, recognizing the neighbor-villain as Raymond Burr, and thereby imbuing the whole dark intrigue with a somewhat different color. Or could this have been at The Blue Gardenia ?)

What do I know about myself during this period? The only artifact I have from fall 1953, apart from the scant information in my diary, is a newspaper headline that I had made up in a Times Square arcade on our way back from Maine: Jonny Rosenbaum Captures Red Spies! So the same Jonny who wept for the Rosenberg boys on the way up to camp must have fantasized capturing their parents single-handedly on the way back. Does this suggest that I wanted to be a hero? Probably; but it was Stanley who proposed the headline while I was trying to think one up—another example, I guess, of the degree to which both of you collaborated on my creativity.

It's only recently that I've come to realize how closely connected my formation as a writer was with your stay at Payne Whitney. Before you left I was already drawing comic books, but my forays into pure writing had been few. My diary, discontinued around the time that you left for New York, was a failed experiment as far as feelings went, merely a list of movies and other activities, provoked by Bo's offer of ten cents per entry and set down with a sense of duty and commitment, with little apparent pleasure or interest. Those things began to develop after you left, when the distance between Florence and New York had to be crossed and I suddenly discovered that words could do it. It became exciting to write poems, parodies of ads (in imitation of Mad ), and newspapers and letters that I knew you would like and would show to your friends. (As I recall, you only played badminton with Robert Lowell while you were at Payne Whitney, but in the sixties I used to imagine that you showed both him and Hodgins some of my first poems.)

The more I wrote, the closer I felt to you. Even my long sentences nowadays sometimes seem motivated by a desire to cross similar distances. And an intriguing aspect of this impulse is that I don't think the Conquistador was the main force behind it. Not at first, anyway; later, perhaps, when the all-male ambience and audience of Surprise Night may have made plots seem more important than words in crossing distances and carrying feelings, but not when I was trying to court you through the mail.

It wasn't the stories of Waterfront and Seven Brides that your letter alerted me to, but the styles and the décors of the movies: the real Hoboken locations of the former, the sets and painted backdrops of the latter. You assumed correctly that the outdoorishness possible on an MGM soundstage (or in a Broadway theater, even if I didn't see that production of Oklahoma! ) was more my style than the outdoorishness one could find on the Hoboken docks, yet you were careful to give each style its due. (This was hardly the case with John McCarten in The New Yorker, who may have influenced your

ideas on Waterfront —"Contributing to the credibility of 'On the Waterfront' . . . is the fact that it was actually made in Hoboken"—but declared himself a cultural cripple when it came to Seven Brides : " . . . a furiously arch movie about the marital problems of a furiously hillbilly family. It's possible that I'm just insensitive to the charm of back-country types, but the insanitary customs of the group assembled here got on my nerves.")

It was years before I became aware of the artifice in each case. I literally didn't see the painted backdrops of Seven Brides in 1954 any more than I could see the relations between the Christ-like martyrdom of the stool pigeon (Brando) in Waterfront in 1955 and the real-life roles of Elia Kazan, Budd Schulberg, and Lee J. Cobb as friendly witnesses in the HUAC purges. But your sense of style began to show me the way. It suggested that stories alone were not what one came away from movies with, that atmosphere and impressions were more enduring. When we saw Julie together at the Shoals near the beginning of spring 1957, I remember that we both felt the same relief when Doris Day finally succeeded in landing the airplane single-handedly: Thank God it was over. Suspense like that was an unpleasant ordeal, a forced march imposed by the Conquistador, not a pleasure, because pleasure required the sort of relaxation that let you observe things and linger. Hitchcock's suspense was different; at least it gave you more to look at.

Rear Window and Waterfront also offered me two ways of regarding New York. As my image of you then was closer to Grace than to Eva Marie, the stylized set that the former moved through seemed more real. Even today, as a seasoned New Yorker, I still believe more in Hitchcock's Greenwich Village—a quiet, elliptical sonata of suggestions—than in Kazan's overwrought Hoboken. Rear Window gave me something that I already knew and recognized: little lighted rectangles of theatrical space, each window across the courtyard from James Stewart framing a separate drama. This was precisely my perception of what our house looked like at night, from the backyard, across the stagelike terrace, when all the lights in the living room, dining room, and bedrooms were on. Just as the two long hallways in the house provided me with an entire childhood of narrative tracking shots (the moving camera writes; and, having writ, moves on), my views of the house from the backyard at night, especially when you and Stanley had guests, were like theater performances, CinemaScope tableaux that held the whole universe in a snugly fixed order, everything securely in its place.

The effect that growing up in that house had on my aesthetic biases must be incalculable, although I certainly wasn't aware of it at the time. In retrospect I'm sure it had a lot to do with my sense of a horizontal line's being both dynamic and restful, which led to my love of CinemaScope as well as the films of Ozu. And the flowing, often subtle transitions between certain rooms might conceivably have helped to prime me for the dovetailing rhythms

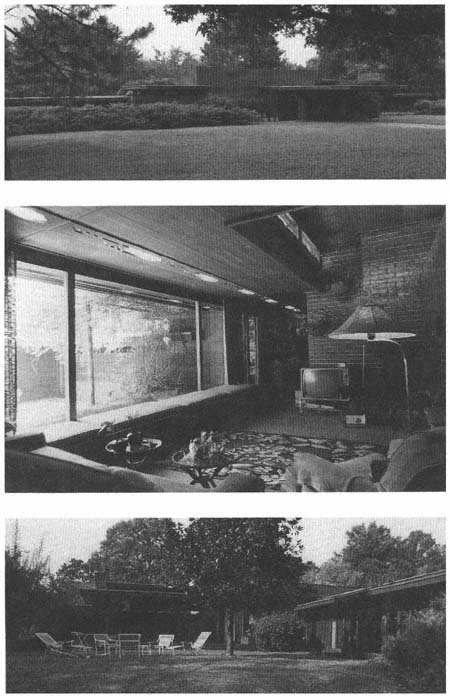

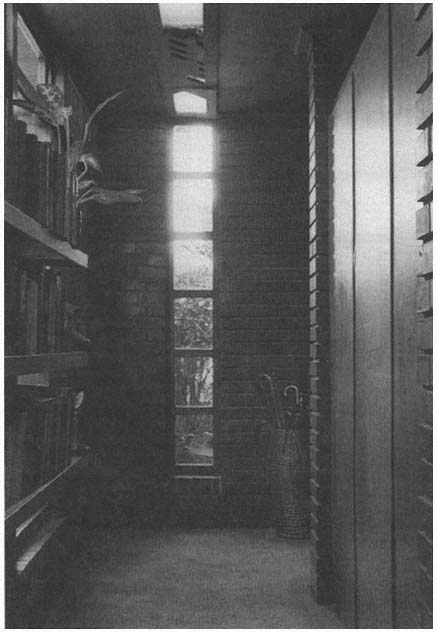

Stanley Rosenbaum house, Florence, Alabama: front, playroom (where I saw Bird of Paradise ), back, front hallway

and continuities of Orson Welles and Alain Resnais. It's an endless game that could be played—culminating, I suppose, in the column of windows in the brick wall at a right angle to the front door reminding me of film frames. Now that I think of it, so do the brick patterns themselves, and the Wright motif in the ceiling light fixture, and Stanley's books on the shelves, and maybe even the umbrellas too. Your three plants on the shelves are the only wild element in this cove of replication and regularity.

I recall a fight we once had within this very space, as I was getting ready to leave for one of the local girls' club dances at the Naval Reserve in Sheffield. It was one of our many fights about the sloppy way in which I dressed and groomed myself. It must have been around 1955, perhaps during the summer-fall period in which Dr. Brown at the Florence Clinic was giving me hormone shots for my undescended testicle. I realize now that James Dean, discovered via East of Eden at the Shoals in late June, three days after my first shot, must have influenced my defiant gesture of twisting my torso in a contorted rage until my ill-fitting white shirt began to tear. Projecting myself back into this rectangular space, I wonder whether those even lines intersected with your anger in such a way that I wanted rebelliously to bend that cumulative line of force, and flexed my body into an expressionist agony of angularity out of, say, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or Ivan the Terrible (or East of Eden , the only example of expressionism I'd seen by then), in order to try, however solipsistically, to snap that line of force in two—ripping instead only the fabric of my frustration.

A comparable fury had driven me, several years earlier, to rebel against those braces with rubber bands in the back that converted my mouth into a dank, Sadean dungeon of pulleys and weights where my tongue would sometimes wander like a fugitive destroyer, slashing loose all the overhead stage machinery that its thrusts could reach—severing rubber bands, dislodging bits of wire. It was a struggle fought in vain, alas, for both of us; damaged braces were always replaced, and no brace could eliminate my slight case of buck teeth. So when I went away to school in Vermont in 1959—a "solution" to my isolation that we reached together the previous year, on one of our Saturday afternoon drives home from Birmingham after seeing our separate psychotherapists (which for you was always a release, but for me another enforced activity, like braces)—I was quickly assigned the nickname Gopher, an appellation that seemed to go with the Northern responses to my Southern accent, both of which kept burrowing to the surface, unexpected and gopher-like, to mock my attempts to escape their baneful implications.

If looks could kill, I reasoned, then so could words. Consequently, during my first two years away from home, in Putney, Vermont, I (1) lost my Southern accent—a cultural delousing process that was a much quicker adjustment for me than acquiring a Southern accent has been for you (over the

past forty years!), but only because the social pressures were greater in my case (Putney in this respect—and many others—being a lot more furiously hillbilly than Florence), and (2) wrote my first novel, which is drenched in Southern accents. In Poe's "The Oval Portrait" the artist destroys his model by painting her; but if all he could paint were self-portraits, wouldn't his work be a kind of suicide? Maybe that's why this book is gradually detoxifying and curing me of movies by providing some sort of methadone of the mind, and by becoming a cemetery for the memories it records, each title a separate tombstone.

Some movies are harder to bury than others, though. I can easily write off Knock On Wood as a romantic digest of what I knew about psychoanalysis in 1954 (Danny Kaye as a schizophrenic ventriloquist who is afraid of women, a cuckoo who almost simultaneously meets and falls in love with—and is treated and cured by—sexy Mai Zetterling, meanwhile capturing a few Atomic spies of his own, in color and Vista Vision), if only because my last look at it—on TV three weeks ago—offered no other lasting revelation. But how can I put Bird of Paradise to rest before I show the reader the room in the house where I saw it almost a year ago; explain that the rich pantheism it stirred in me was a direct legacy from you (outdoorishness in another form); and note that the 1954 nightmare it influenced was dreamt during your second visit home from Payne Whitney? And what about On Moonlight Bay , a corpse I had occasion to revisit in the TV morgue over five weeks ago? This time I could only chide the movie for its unfaithful departures from my text: the mispronunciation of Hubert Winkley's name as Wakeley, for instance, and Miss Stevens's sending the rest of the class home directly after Wesley calls her an old crow (instead of waiting until after school or during recess to see him).

If looks can kill or create, I'm sure that words can, too. In precisely that light, where words and appearances become equally powerful in their claims to define reality, Freaks was surely the most formative and traumatic film of my youth. The dichotomy begins with the title, which gave me at the age of seven just as many creeps as some of the images. As I recall, the freaks are first glimpsed relaxing in a peaceful forest clearing in France. The game warden complains about them to his master, calling them "horrible, twisted things." We see them crawling and wriggling about in an unsettling, indistinct long shot. But the normal French lady who runs the circus, their custodian Madame Tetrallini, passionately defends them in a warm, closer shot, drawing them into her arms' maternal shelter as she cries, "These are children in my circus . . . That's what most of them are, children ." The alternative description and camera position transform the essence of what both we and the master see: they are sweet, helpless creatures, not monsters. Later other ver-

bal and visual cues will turn them into monsters again, and still others will make them sympathetic and likable adults. (This was suggested to me in part by Jean-Claude Biette's article on Freaks in Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 288, May 1978.)

You've never seen Freaks , Mimi, and I'm sure that you never will; as you said to me about Waterfront , it's not your style, so you'll have to take my word for it (or Stanley's) that the movie is profound and humane about its subject and not at all complacent. Metaphorically, I think one could say that it shows a lot of what goes on for real . I've seen it three times: August 31, 1950, at the Majestic (in defiance of Stanley's warning, along with David and Alvin); October 2, 1964, at Bard College (where I programmed it for the Friday night film series, on a double bill with The Phenix City Story ); and last summer, August 25, 1978, at Theatre 80 in lower Manhattan. On the basis of my last look at it, I'm prepared to consider it an aesthetic experience and a political statement that I was too young, rattled, and brainwashed to recognize as such at the ages of either seven or twenty-one—an assault on the ideology of beauty that rules us both, and all the everyday unthought cruelties that this ideology permits, authorizes, even encourages, in others and to others, in ourselves and to ourselves. Which is not to put down or to exonerate either of us; it merely acknowledges a system of beliefs and habits that is an intimate part of both our lives, for better and for worse. What you find in a mirror is pretty close to what I look for, in a page or on a screen. Our aesthetic biases become our objective realities because we like reality better that way, with the right appearances.

That's why you once designed a house for our collie Diana which matched our own, and had a carpenter build it; and why Diana, pragmatic nonaesthetician and philistine non-Wrightian that she was, took one trip inside, emerged, and never reentered, preferring to sleep in the little alcove outside the playroom and leaving your creation to us, for use as a playhouse.

We both like to spend a lot of time at home, in our own rooms, creating our own sense of order. That's why I'd like to think that, over the years, some of the same energy that flows through your looms passes through my typewriters. Astrologically, we're a crab and a fish who swim in the same ocean. (The Conquistador wants us to march, but mainly we float instead.) . . . It's taken us years, but you've taught me to hear the sound of your own voice, and both our lives are richer for it.

Love,

Jonathan

P.S. If a movie called Remember My Name gets down to Florence, be sure to see it—I think you and Stanley would both go for it. It stars Geraldine Chaplin, and she really gives a fantastic performance.

II

Of married ones and single ones

And families and daters

There's fun for all of you this week

At the Muscle Shoals Theatres!

"Three Stripes in the Sun" is the name of one

That's playing the Shoals today

It concerns an Army sergeant

Better known as Aldo Ray.

"Blood Alley" refers to the Formosa Straits

A dangerous part of the ocean

Where Communists, storms and Lauren Bacall

Keep John Wayne in perpetual motion.

—from Stanley Rosenbaum's Sunday column, Florence Times , January 8, 1956

Sometimes it wasn't the movie at all but the configuration that went with it, or came out of it, or burned straight through it like a dropped cigarette—the static image summoned up by title, poster, billboard, newspaper ad, review, or some other form of promotion. Or maybe it was the false yet enduring and prevailing expectation. As Alvin said to me in Washington three months ago, Movies used to be the Rosenbaums' Muzak —forever buzzing, blandly and gleefully, in the backs of our minds; and meanwhile adding up figures, busy as bees.

In some cases it might have been just a bit of ballyhoo that the theater manager devised, the real-life ads he staged, such as the giant robot from The Day The Earth Stood Still —or rather, a noble facsimile built by Bobby Stewart, the Shoals manager—patrolling the center of downtown Florence during the last shopping week before Christmas 1951, or the "moonshine still" that Aston ("Elk") Elkins rigged up at the Colbert to push Thunder Road in 1958—a funny prank to play in a county where bootleggers and churches have joined forces to keep liquor illegal since 1952. (When I saw Bird of Paradise during the spring of 1951 in the adjacent county—which has been dry since time immemorial—all those drives across the river, mainly to Sunday school or the Sheffield and Tuscumbia theaters, past all those beer stands and bars and neon neo-nightclubs, conveyed to me at eight a warm, goodnatured, uninhibited paganism that I could immediately ascribe, like a credential, to Kalua's heavenly tribal people, that happy-go-lucky, pre-hippie, pre-Panavision, pre-Jonestown extended family unit.)

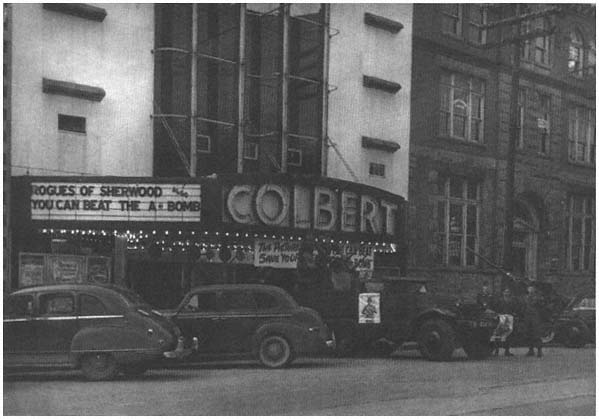

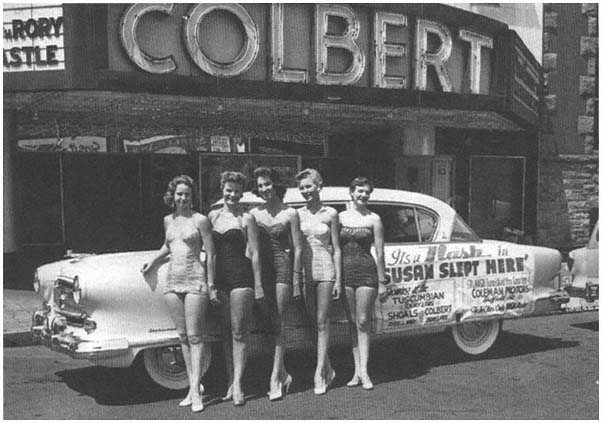

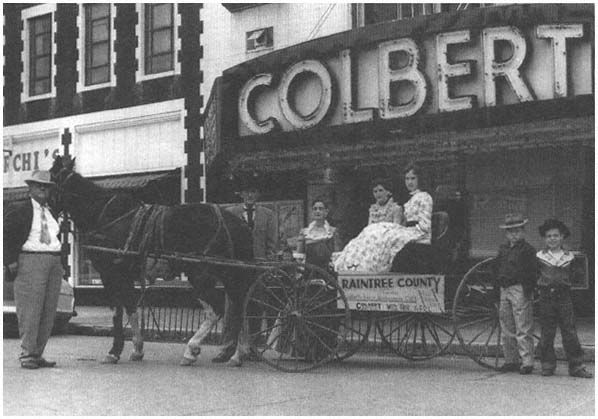

Promo gimmicks like those shown here were one of Elk's specialties when he managed the Colbert. For Thunder Road he built that "still" and put water in it and a fire under it, and before long his mother and father-in-law

Aston Elkins ballyhoo, Colbert Theatre, Sheffield, Alabama, December 22 or 23, 1950

Aston Elkins ballyhoo, Colbert Theatre, Sheffield, Alabama, September 9 or 10, 1954

Aston Elkins ballyhoo, Colbert Theatre, Sheffield, Alabama, March 1958

had phoned his wife Mae Murray to ask whether he was in jail. That's the honest truth.

"Paul Harvey got aholt of it in some way on his news," Elk says grinning, flushed as a beet, in the Rosenbaum living room on March 19, 1978, where he and Mae Murray and Bobby Stewart and Stanley and Mimi and a current local theater manager my age, W L. Butler, and his wife Diane and I are all sipping coffee this Sunday afternoon and talking about the theaters. "And it got into every newspaper." "It did," says Mae Murray, "it went all over." Another time, to promote a horror film (he doesn't recall which one or when it was ) Elk borrowed a casket from his brother's funeral home and filled it with a department store dummy that he covered with catsup. Ever since the Colbert was demolished Elk has been working with real corpses in his brother's business. Bobby is still a sign painter, and one of the best.

Sometimes it was the accompanying routine, like Daddy's checking up, a ritual he performed five or six nights a week, every night but Surprise Night, usually alone, sometimes with Mommy, sometimes with one or more of us (on weekends or on a special holiday or during the summer, when we could stay up later), always leaving the Shoals sometime after nine to drive across the river and pick up the final reports at the Colbert and the Tuscumbian, always returning well before eleven.

A routine so absolute you could check the order of the universe by it. Jonathan, living in France, found himself recalling it each time he attended the Cannes Film Festival (May 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973), whenever he began restlessly to make the rounds of all the places he habitually passed through. He would begin at the Carlton lobby, with its huge square glass ashtrays resting like miniature swimming pools on the spacious marble reception counter, then walk past the shrieking, waving billboards and banners to the Petit Carlton a few blocks away, a noisy, crowded bar for sailors and journalists without expense accounts (like Jonathan, a stringer for the Village Voice, Time Out, and Film Comment ) on rue d'Antibes, a narrow "main street" that led to most of the smaller hotels and cinemas. Then he'd proceed back around the crowd in front of the Grand Palais and all the way down the white hot and blue cool line of ritzy seaside hotels toward the casino, ceaselessly coveting and recovering his happy stations of the Croisette between movies while looking for friends, colleagues, acquaintances, or others whom he could never meet properly in Paris, even though he'd been there since the fall of 1969. Maybe it wasn't so much checking up as checking things out—perhaps even scaring things up—but it brought back hints of Stanley's bright pleasure in compulsively repeating a regular itinerary of stops, surveys, pipeloads, and amiable chats.

If the Conquistador had had a radio or TV show of his own in the mid-fifties (we would have watched the latter on our first set, Bo's twenty-one-

inch RCA that he gave us for Chanukah in 1954 when he got himself a larger model, at the same time that Stanley and Mimi bought me my first typewriter, a Smith-Corona portable), he might well have wanted to call his program Checking Up . And if he had gone on the air with it often enough, we would have gladly listened to and/or watched it instead of movies. It was always a narrative, a story in which Stanley Rosenbaum was either the hero or the narrator and the listeners/spectators were the inhabitants of his Indian red 1953 Pontiac station wagon or his green 1949 Oldsmobile as he drove across the river and back to pick up the final reports from the Colbert and the Tuscumbian. The whole trip took about an hour, stops and commercial breaks included.

What was so wonderful about checking up? It wasn't exactly a western, though it had a few things in common with some of them, a relationship enhanced no doubt by the fact that we most often went with Stanley on Friday and Saturday nights, which also happened to be when westerns usually played. First, you rode somewhere, making stops along the way to pick up important information. Second, adventures and spectacles en route were always a possibility; once, in the mid-fifties, a locust attack swamped the windshield as you and Stanley, alone in the car, were crossing O'Neal Bridge from Sheffield to Florence. Third, women usually didn't come along for the ride, though they were always waiting faithfully at the stops. These were mainly (apart from Mimi) the box office cashiers, who had to total the number of tickets sold (and how many of each kind—adult, child, student, colored) and the amounts of money made in tickets and concessions. They would also fill out a form, noting the starting and ending serial numbers on the tickets sold that day, which Stanley would collect. In the meantime, the manager would have placed the day's proceeds in a canvas bag, deposited it in the night vault of the local bank, and returned to the theater before Stanley arrived.

Sometimes Mimi came along on weekends, though she preferred weeknights (after seeing an early movie with Stanley), when she didn't have to compete for his attention. She didn't like getting out at the Colbert and the Tuscumbian with the rest of us. The cheesecake on the walls of Elk's office made her uncomfortable, and by the time we reached Tuscumbia (entering from the north, just past the turnoff for Helen Keller's birthplace) she had usually located some classical music on the radio. She would listen to that while we went with Stanley to see Jimmy Hall or Walter Arsic, the manager at the Tuscumbian, or perhaps we would watch a portion of the last feature while Stanley took care of business. We stood in the back of the auditorium until he tapped each of us gently on the shoulder and said, "Time to go, Butch."

The warm familiarity of checking up had a lot to do with the places you passed, the people you saw when you stopped, and the fragments of movies you glimpsed, usually morsels of movies already seen at the Shoals or tanta-

lizing previews of what was coming shortly. (On Friday, May 17, 1957, it was Teahouse of the August Moon —already seen last Sunday—at the Colbert; and Giant—running concurrently at the Shoals, where the whole family would see it the day after tomorrow—at the Tuscumbian.)

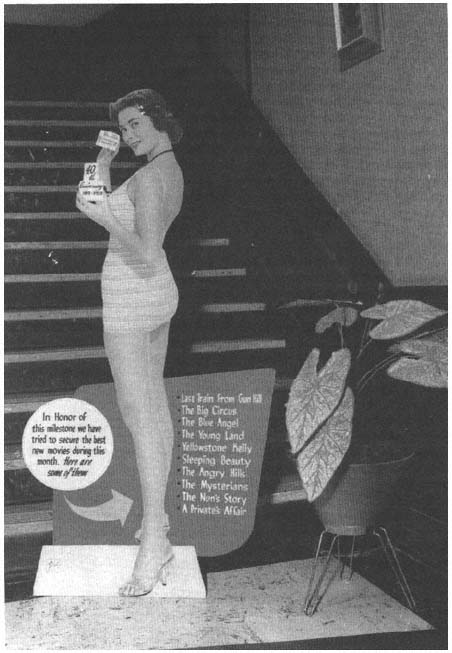

Sometimes, if you arrived at either theater far enough ahead of schedule, before the last feature had begun, you'd see trailers (the trade term for previews) you had already seen at the Shoals as well as trailers that were new to you. Outside, under the marquees, you could study the paper advertising, the one-sheets and three-sheets and picture cards for the movie that would be showing tomorrow, while inside, in the lobbies, there were additional one-sheets for future attractions (and occasionally a special display, such as this one by Elk in 1959). Further inside, at the back of each auditorium, next to the semidark areas where we stood watching fragments of the movies, were the bright green and red CinemaScope-shaped lobby cards, sprayed with the magical hue of violet fluorescent bulbs inside a vertical Day-Glo display case, announcing attractions that were even further off in the future—like the serial numbers of the tickets for any given day, a chain that stretched forward and backward in an infinite series, neither progressing nor regressing as it proceeded in two directions, endlessly, beyond any human ken.

An only child, Stanley didn't like checking up by himself, so he sometimes invited friends to come along. One of them was A.G., a good-natured fellow who was missing an arm, read a lot, and was a fan of Ray Bradbury, Jonny's favorite author from Surprise Nights. He was also an epileptic, which was how Daddy met him in the first place, after he had had a fit in the Shoals balcony. He had lost his arm when he was a kid, holding on to the back of a truck while riding a bike. Mommy never liked to check up with Daddy when A.G. came along; she agreed that he was a nice man, but being around him made her skin crawl—one of those feelings that wasn't his fault and wasn't hers.

The grand climax, the final dramatic cymbal-clash of checking up, always occurred before Stanley returned to the Shoals. One felt it building up during the long drive back from Tuscumbia to Florence, Stanley's route nearly always taking one through Muscle Shoals City. There he'd automatically reduce his speed in order to avoid getting a ticket (it was a speed trap before becoming a music and recording center in the sixties and thereby expanding the Tri-Cities into the Quad Cities), passing the Park-Vue Drive-In (today the Marboro, where W.L. is the manager), which belonged to a competitor yet afforded a quick, fragmented glance of still another movie. After passing a small patch of government-owned TVA property, Stanley would retrace a portion of his route into Sheffield by turning right at the intersection where Ron's Gym is today, less than a quarter of a mile from O'Neal Bridge. Finally, after recrossing this bridge back into Florence and proceeding gradually up the main drag toward the high embankment facing the river and the

Aston Elkins ballyhoo, lobby display for the fortieth anniversary of Rosenbaum Theatres,

Colbert Theatre, Sheffield, Alabama, summer 1959

Sheffield palisades, you would pass on your left the twenty-four-sheet announcing the next big movie at the Shoals, a giant billboard smiling down on your return to Florence like a divine countenance, perhaps with the face of a pretty woman, reminding you how nice it was to be home again.

I've never seen Behind The Rising Sun , but this ad was a familiar one throughout my childhood. It appeared with two intriguing variations in the July 24, 1943, Showman's Trade Review, an issue that featured Bo on the cover ("business and civic leader . . . now serving his second year in the chairmanship of district 1 for the Alabama War Chest appeal by appointment of Gov. Chauncey Sparks . . . " says the blurb inside). I must have looked through that magazine dozens of times in Stanley's office over the years, usually while waiting to go home with him after having seen a movie next door at the Shoals. It was kept in the same low bookshelf that housed all the Motion Picture Almanacs , and as a rule I would resort to it only after I had gone through the latest Time or Boxoffice on the desk.

My memory of this ad ("exterminated," the title, and the message at lower right are rendered in bright blue) and its two companion pieces elsewhere in the issue (identical themes and credits have slightly different characters and texts, and red or orange letters instead of blue) gradually became interwoven and intermixed with afterimages of movies I had seen, a long, rich anthology of monsters that included

the Japanese insect torturers of The Purple Heart (1944), a reissue at the Princess in June 1950;

Ming the Merciless in a Flash Gordon feature digested from a thirties serial, at the Shoals some time in the mid-fifties;

the invisible, all-destroying title feline in Track Of The Cat (Shoals, April 1955);

the quasi-visible barbarian Indians at the beginning of The Searchers (Shoals, June 1956);

the visible but faceless villains of Rio Bravo (Cinema, May 1959);

the Mongolian savages at the end of Seven Women , John Ford's last film, seen with Carolyn Fireside at Studio Cujas, October 10, 1969, three days after I moved to Paris;

the Vietcong gooks in The Deer Hunter , seen in a midtown Manhattan screening room on December 12, 1978, the day before I flew to Berkeley (and wrote my review of this movie for Take One );

and countless other xenophobic images in between.

Of course there are significant differences between these images. The Japanese insect torturers in The Purple Heart (reseen at the Museum of Modern Art, February 1979) appeared at the same time that the United States was at war with Japan, and a few clumsy attempts were made to give human

Advertisement, Showman's Trade Review, July 24, 1943

(i.e., American) characteristics to these strange people from afar. By contrast, the Oscar-winning racism of The Deer Hunter was articulated, enjoyed, and rewarded in mid-April 1979—several years after the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam—and no effort whatsoever appears to have been made to humanize its buglike villains.

Suggested pastime:

1. Run through any movie, good or bad, frame by frame, until you arrive at your favorite frozen instant, the point at which characters, emotions, sets, and ideas suddenly merge in an ideal symbolic configuration that conveys a maximum of unified meaning within a minimum of space and time—an orgasmic flash of signification that strikes like lightning between two bats of an eyelid, which any idiot (like you or me) can read at once.

2. Got it? Now hold on to it for dear life. Throw the rest into the disposal unit, for eventual retrieval by nostalgia (a term coined in 1688 by Johannes Hofer, an Alsatian medical student, derived from Greek roots meaning "return home" and "pain," and regarded as a medical problem through the end of the nineteenth century), but don't let go of the snazzy book-jacket logo, that relic which can somehow stand for all the rest. Keep it securely locked in drawer or cabinet, protected in a plain brown envelope. Maybe, if you're lucky, it will be available in several sexy poses (the ad for Behind The Rising Sun generously offers not one but two "villainous Japs [manhandling] captive women," one woman with a baby and one without; and if I could show you the two variant ads in that issue of Showman as Trade Review, you would have at least as many images to choose from as in a typical Playboy feature spread).

3. Take out this favorite image once a day and stare at it for at least five minutes, ridding your thoughts of everything else. Recite the film's title over and over like a mantra. Varying the emphasis on words or syllables in the title is permissible (e.g., The Deer Hunter, The Deer Hunter, The Deer Hun ter, The Deer Hunter ). Take a deep breath. Repeat exercise.

4. Watch the Academy Awards presentation on TV once a year, preferably on an Advent screen.

"Who Wins Ava?" reads the caption in the newspaper ad for The Little Hut (June 9, 1957), over a cartoon desert island hut on steep poles that is entered by ladder. A giant photograph of Ava Gardner in the foreground shows her standing in a dark, gauzy, almost see-through nightie, her ample legs crossed. Part of her body, including her right arm, is cut off by the left border of the ad; her left arm hangs saucily over her hip. Around her are diminutive cartoon figures recognizable as Stewart Granger and David Niven, urbane English Lilliputians to this female American Gulliver. Granger, in a white tux, stands at the base of the cartoon hut, arms and legs both crossed, looking

up at a little dog standing inside the threshold; Niven, in shirtsleeves, crouches on all fours at Ava's feet, his nose aimed (more or less) at a spot directly between her legs.

The movie is awful, Jonny discovers to his regret at the Shoals the same day—another grim exercise in blocking libido with frustrated giggles, served up in "blushing" MGM Technicolor yet delivering absolutely none of the scintillating perversions promised or suggested in the ad. Yet this doesn't prevent the ad from furnishing the décor and determining the mise en scène for at least three of his most sublime teenage orgasms afterward. So what if one winds up believing in the ad but not in the movie it describes? Just as many—perhaps most—films exist solely in order to "maneuver two or three scenes into position to maximum effect" (as Ray Durgnat puts it in a discussion about nonnarrative that he and I wrote together in Del Mar last spring, along with David Ehrenstein in L.A.), the ideal form and expression of many films can be found only in the ad or title—an emblem, unlike the movie, that we can sometimes keep.

Longer lasting, too—like Debra Paget's delicate Polynesian feet in Bird of Paradise , after she has walked barefoot on red-hot coals to prove that her love for the white man, Louis Jourdan, is good and true. "You're not burned!" he exclaims, examining her feet afterward. "No," she says calmly, "I did not feel the fire." "But I stood there—I saw the fire in the stones. This is incredible!" "We have the answer ," she says, joy sparkling in her eyes. "The gods have smiled on us. Now we can be one . Now you can buy me." "Buy you?" Louis asks, incredulous. "Yes, from my father. It is the custom," she says with a tender, loving laugh, taking pleasure in his innocence, starting now to tease him. "I will be very expensive . . . " "You will be worth it," he responds in deadly earnest, not long before the impending volcanic disaster strikes.

Sometimes the title was more than enough. I can't remember much of I Wake Up Screaming , seen at least one and one-half times on a Saturday night (November 20, 1948) at the Princess, while waiting to see Lash LaRue, on stage in person, pop the top off a Coke bottle with his bullwhip. All I can recall is a shot of Betty Grable on the telephone and the curious experience of stepping behind this gigantic image in order to meet Lash in his dressing room backstage. But the title scared the living daylights out of me at five, and it continued to do so for years afterward.

Sometimes all it took was an unexpected hookup between movies and life. Movies were our Muzak then, so the distinction wasn't always clear-cut. I can't remember exactly when in the early fifties the whole family went to the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus in Memphis and found none other than Harry Earles, the midget in Freaks , featured in the sideshow. Yet I still recall that I was the only one of us unwilling to go over and talk to him. Persuaded irrationally that the encounter could only make the movie

seem more real, not less, I was still more than a quarter of a century away from the perception that the movie's disturbing effect on me in August 1950 was mainly an aesthetic one, not the effect of a "documentary" rendering of any sort of reality, however horrible. Instead I froze into a sort of adlike tableau off to the side of the raised platform inside the tent, turned away from the others on my little patch of sawdust, hints of tears tickling the edges of my eyes as I stood petrified, refusing even to look at him.

Stanley chided me later for my hypersensitivity: "He's friendly, Butch, and very intelligent. And he's real, not just a character in a movie." I'm not at all sure that I understood precisely what he meant. Maybe it was better that I didn't understand; displays of sensitivity were an essential part of my vanity, a virtually patented counterpart to David's jock and macho credentials, so why should I relinquish any part of their justification? And why should I again have to confront my confusion about my sexual identification with Earles in the movie? (The identification seems closer than ever when I return to Theatre 80 on Saturday, April 28, 1979, to see the movie a fourth time. Two weeks later, after reading a copy of a treatment of Freaks that was circulated at MGM in 1931—and lent to me by Elliott Stein, a friend, colleague, and SoHo neighbor—I conclude, as I type this sentence, that sex really was the structural glue that held the scenario together before studio and censors began cutting things out, mutilating the movie just as the newspaper ad for The Little Hut mutilates Ava Gardner by removing her right arm and shoulder, thereby making her an even more erotic fantasy—a "total object, complete with missing parts, instead of partial object," as Beckett puts it—that is completed by the imagination invested in the spectator's gaze. No wonder that the first time Elliott saw Freaks, in Manhattan in the thirties, it was showing on a double bill with a porn film.) And no wonder that Earles's plight in Freaks seems so close to that of Emil Jannings in The Blue Angel —a grown man driven berserk with passion by the enormous thighs of a beautiful, cruel, seductive showgirl.

[Monday, December 21, 1953]

Dear Mimi,

As you know, I committed myself long ago to taking the kids to see "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes" whenever it showed again locally. I mentioned in yesterday's letter that it was to play at the Park-Vue last night and that I was to take the kids. The mission was successfully accomplished, but at a grave cost in blood, sweat and tears. As one of the triumphs of the human spirit against formidable odds, I rate it only slightly beneath the Conquest of Everest.

Preparations

Transportation Problem Which car to take? The station wagon is no good for a drive-in because of the tinted glass in the windshield; the Oldsmobile, because the sunshade blocks the view. Solution resolved upon: Borrow the

folks' Cadillac. Exchange of Oldsmobile and Cadillac effected in front of Shoals. Mother and Dad proceed home in Oldsmobile. I get in the Cadillac and start looking for the car keys. Can't find them. Have vivid recollections of Mother handing them to me a moment before. Nevertheless, they are not in my pockets or apparently anyplace else. (She handed them to me while we were in the Olds in front of Elk's after leaving his "at home." I go back to Elk's, borrow a flashlight and search the gutter and nearby grass.) I call Mother and ask her to see if I had dropped the keys in the Olds. She and Dad are both undressed, but she dresses, looks in the Olds and can't find them. Then she drives to the Shoals and gives me her second set of keys. A few minutes later, when I am driving the Cadillac, I hear a clink at my feet, and there are the missing keys on the floorboard. They apparently dropped from my clothes someplace.

Personnel Problem James is coming to work and naturally we want to take him in the car with us.[*] This may be against the segregation law. Is the drive-in going to be technical about it and embarrass us? Alvin is staying at Rossie's, but very much wants to come. We arrange to pick him up and we invite Judy too. High conclave of Klibanoffs to decide whether Judy can go. Verdict: No. Judy retires to her room, feeling unjustly treated, and sulks. (Cf. Achilles brooding in his tent, Iliad, passim.)

Seating Problem All four put in a claim to sit by me while we watch the picture. Only one can. David bases his right on priority of request, Michael on his youth, Jonny on the history of past injustices suffered, and Alvin on the idea that because he was staying at Rossie's he wasn't seeing much of me, but the others were. They all put in a second choice claim for the other place in the front seat, and nobody would settle for anything less than a seat next to the window in back. But also no one would give up what they felt to be their inherent right to the seat by me. Tempers flared. Arguments grew louder and more simultaneous. I restored order hastily and suggested that we write all the positions on pieces of paper (after automatically and unanimously awarding the middle of the back seat to James) and draw for them. This was agreed to by all, but a new fight immediately broke out on who should draw first. I allayed the tumult with an arbitrary decision that the youngest should draw first and the others in order of ascending ages. David was disgruntled by this until he drew, and then was happy to have gotten the #2 position, by the window on the front seat. Alvin got #1.

Interlude: We ate supper inside at Sam Basil's place, on Tombigbee, after another argument about who would sit where.[**] We were somewhat pushed for

* James Thompson was a black high school student who worked for the family as a babysitter during most of the time that Mimi was away at Payne Whitney. Whenever he stayed over, he slept in the front bedroom, and in the morning Stanley always dropped him off at his school first, so he could work in safety patrol. (J.R.)

** In the back of Sam Basil's—subsequently known as The Shanty, where Jonathan and Ron Russell used to hang out in the sixties (it was torn down in the seventies)—was a room with separate private compartments and tables blocked off by partitions and curtains. This allowed the Rosenbaums to break the Jim Crow laws by eating with James without being seen by other customers. (J.R.)

time (after the show, I had to return to Florence, switch cars, deliver the kids to various places, and get back across the river in time to check up), but the kids were in good humor and ate well.

The Ordeal Begins We arrive at the Park-Vue. No trouble about James. We are recognized and they won't charge us anything. It is now the middle of the feature. It has been sprinkling off and on all day, but we had decided that it was about to stop. As soon as we have parked in position to watch the show it starts raining in earnest. We try running the windshield wiper. It is very distracting. We turn it off from time to time. Whenever it is turned off, it blocks David's view. Michael complains that he can't see at all. We change his seat with James, and perch him on the armrest in the middle.

The Darkness Thickens After a while, we are running the windshield wiper all the time, and of course, the motor too, in order to operate the windshield wiper. We alternately keep the windows open and shut. When they are shut all the windows steam up rapidly and we can't see a thing. I would be disposed to accept this state of things quite cheerfully, but the kids object. So we open the windows. The glass clears, and also Jonny is enabled to stick his head out of one of the back windows, which he claims is the only way he can see. But the rain drives in on all of us, it is cold and windy, and James, who has a cold, starts sneezing. So we close them. Then we open them again. Etc., etc.

The Survivors Beginto Despair The movie is ghastly. I keep telling myself it can't be as bad as it looks, but I can't convince myself. The heavy rainfall has affected the screen so that large areas simply reflect light, without any picture at all, like pools of quicksilver. Visibility is so bad that I can amuse myself (somewhat ironically) by trying to distinguish Marilyn Monroe from Jane Russell. We are on a slope, and the car tends to slip a little occasionally. This will break the speaker cable if not checked immediately, and on one occasion we actually had to jettison the speaker hurriedly to keep from snapping the wire. Incidentally, the maximum volume on the speaker finally settles down to a loud whisper. If anybody in the car makes the slightest noise, you can't hear the speaker. Someone is always making a noise.

Interlude Il—Intermission: David undertakes an expedition to the Snack Bar for provisions. Michael demands a snow man (ice with syrup poured over it). Daddy refuses Michael a snow man on the grounds that it would mess up Bo's car. Michael accepts the compromise of a box of popcorn, but it is quite clear that he considers himself a victim of inhuman treatment.

Foray Into Enemy Territory The show begins again. I enjoy the commercials, but all too soon we are back to the feature again. The rain comes down harder than ever. Michael informs me (with a hint of sadistic pleasure in his voice) that he has to go to the bathroom. Nerving myself, I grasp his hand and we plunge into the storm. Soon we are at our haven, an unlovely but functional place. The walls are covered with quaint native inscriptions. Michael is affronted by a new blow at his dignity. The urinal is placed too high on the wall for him to reach. I point out that the other fixture in the room is at the usual humble distance from the floor, and he quickly takes

advantage of the hint. We strike out again into the darkness and storm, and soon reach the car. I regard this whole incident as definitely the bright spot of the evening. We missed at least ten minutes of the picture.

Internecine War Breaks Out We are now back in the car. The loudspeaker is murmuring hoarsely. The windows are open just enough to clear the mist off the windows. The windshield wipers are slapping back and forth. Michael is sitting again on the armrest but apparently in a somewhat different position than before, as Jonny is now in his way. Jonny tries several positions, but every one in which it is possible for him to see the picture at all, makes Michael very uncomfortable. Sharp words fly back and forth. Michael is obstinate. Jonny gives in, but bewails bitterly that he can no longer see anything at all. (He doesn't know when he is well off.)

Even the Weariest River Winds Somewhere Safe to Sea David, with his sharp eyes, discovers that the picture is now back to the place where we came in. We start back! It is 9:10, time for me to make all the necessary stops. We churn through some muddy roads leading off in uncertain directions, but finally get back to the highway. Michael had brought some plastic fish in the car which Hank had given him. Now he can't find them. The light is turned on and everybody in the back seat looks, but they are nowhere to be found . . . Jonny says that "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes" will eventually come to the Norwood as a double feature, and that when it does, he intends to go and see it . . .

Love,

Stanley

These were the years of Jonny's apprenticeship in the business, a time for learning how to function outside of movies yet somehow in intimate relation with them. Late spring 1954, after attending the exhibitors convention in Atlanta for the second year in a row, he again accompanied Stanley on his visits to the Atlanta offices of the film companies—Columbia, MGM, Monogram, Paramount, Republic, Twentieth Century-Fox, United Artists, Warner Brothers—to book movies. At the last of these places (alphabetically and chronologically) Jonny suggested that Stanley book Jack and the Beanstalk , with Abbott and Costello, and The Lion and the Horse , with Steve Cochran, as a second-run double feature at the Princess for its Wednesday–Thursday Thanksgiving program (he thought kids would like it); and Stanley, really pleased with the idea, did precisely that.

During the same trip to Atlanta Jonny saw his first demonstration of Vista Vision. When he remarked to Bo a month or so later that he thought that CinemaScope was better because it was bigger, his grandfather was so delighted with the phrase that he got Stanley to add a snappier version ("It's bigger! It's better!") to the enormous Sunday ad for King Of TheKhyber Rifles in the July 12 Florence Times . All this culminated, more or less, in Jonny's taking over Stanley's Sunday column in March 1957 on a one-shot basis, describing that week's main films (The True Story Of Jesse James ,

Fantasia,The Beast Of Hollow Mountain , Six Bridges To Cross , Ain't Misbehavin' ) with the help of pressbooks, and, at age fourteen, making his first published pronouncements as a film critic.

Not all the sequences [in Fantasia ] are stories, but they all are thoroughly enjoyed by children and adults alike. In this movie hippopotamuses dance, Mickey Mouse practices magic, fairies and brownies celebrate, and brooms march—just to mention some of the unexpected events of this film. The picture is very colorful and will be remembered for a long time. Along with the feature there's an Academy Award-winning CinemaScope Disney cartoon, Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom . I've seen this cartoon myself out of town a few months ago, and frankly it's the best cartoon I've ever seen. Colbert: Monday and Tuesday. Shoals and Tuscumbian: Thursday and Friday.

Taking over Dad's column didn't seem at all like advertising to me; it was more like a personal declaration, This I Believe. Twenty-two years ago I was more or less pretending that my advertising copy was criticism. This is something that all critics do all the time, that I continue to do on this early morning, May 1, 1979—George Axelrod's brilliant Lord Love A Duck of 1966, in glorious black and white (see what I mean?) on Channel 7—or when I write articles for American Film and reviews for Take One in order to buy more time for this book (can I finish a first draft before Sandy moves here?). Everything always pays for something else in the long run, toting up figures, piling up goods the way that Tuesday Weld's daddy buys her sweaters, flipping out in a prolonged incestual frenzy as she slowly and deliciously recites and he deliriously and joyfully repeats the styles and flavors of all the sweaters that she models vivaciously for him—Grape Yumyum, Lemon Meringue, Pink Put-on, Papaya Surprise, Periwinkle Pussycat. Like those people on the screen, like me in 1946 and 1957 and 1968 and 1979, I just go on making money off movies, moving places and placing movies, all the time, in every way.

And that's just one of my ways of being like Stanley, which was something I wanted to do in every possible respect, from handwriting to typing to reading to ordering my hamburger steaks well done. Or seeing an exciting movie with him like The Narrow Margin , Saturday night, August 30, 1952, right before checking up, the two of us sitting in the Shoals balcony so that he could smoke his pipe, both of us enjoying the terse, macho wisecracks that breezed back and forth between Charles McGraw and Marie Windsor, both of us loving the fact that practically all of this hardboiled black and white thriller was set on a train and that the fat man—for both of us, a Bo surrogate—turned out to be a good guy, a plainclothes cop traveling incognito.

Hardboiled or not, the one kind of soap opera in the early fifties guaranteed to get me blubbering helplessly or glowing incandescently was the father-and-son sob stuff, especially when the son was a little boy. You know

the kind: William Holden (Uncle Johnny Rutledge) becoming a daddy to five fatherless kids named after the months in Father Is A Bachelor (1950) and singing "The Big Rock Candy Mountain" to cheer them all up (in a dubbed voice, Jonathan notes glumly in Del Mar on September 23, 1977) or training a homeless boy to be a jockey in Boots Malone (1952). Or Red Skelton losing his son because of his drinking in The Clown (1953); or even that voluptuous, devouring moment of love and acceptance at the end of The Window (late September 1949), when Bobby Driscoll, the boy who cried wolf, was finally believed by his parents (Arthur Kennedy and Barbara Hale), made safe and secure from the stalking killer, and hugged by both of them at once in the back of that cozy dark cab, sheltering him in their forgiveness and warmth. ("Now showing for the 7th week on Broadway at $1.50," Stanley's ad in the Florence Times pointed out, after mentioning that at the Princess it was only ten cents for children and thirty-five cents for adults, "selected by Time Magazine as 'Current and Choice.' Added: Leon Errol in Uninvited Blonde .")

Was it a buck fifty that the World Theatre (on 49th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues) was charging for Bicycle Thief at the time of our family trip to New York, the last week or so of June 1950? We'd all gone to see One A.M. and The Kid at the Museum of Modern Art, City Lights with Norman McLaren's Begone Dull Care at the Paris (children fifty cents at all times), South Pacific with Mary Martin and Ray Middleton at the Majestic, Peter Pan with Jean Arthur and Boris Karloff at the Imperial, George C. Tilyou's "Steeplechase the funny place" at Coney Island (admission plus any six rides, fifty cents; any twelve rides, one dollar), The Next Voice You Hear with the Gala Two-Part Holiday Stage Show at Radio City Music Hall (the two parts were "Let Freedom Ring, thrilling patriotic pageant" and "Shoot the Works, dazzling extravaganza with Rockettes, Corps de Ballet, Glee Club and Symphony Orchestra . . . climaxed by a gigantic fireworks display ").

Whatever it was, the World was too expensive—no children's prices of any kind—so Daddy took us all to see Destination Moon instead, at Brandt's cool Mayfair. We had already seen the gigantic neon sign for it from the window of Uncle Arthur's office high above West 46th Street, so it seemed like the logical thing to do. Yet I couldn't hold back my tears of disappointment. For Daddy had already told us the plot of Bicycle Thief , and the story of the man and his little boy looking for his stolen bicycle so that he could work was the saddest thing I had ever heard (I still didn't know about tragedy, which would come with the synopses of The Great Caruso , Oedipus Rex, and Hamlet the following spring)—sadder even than parts of Huckleberry Finn, which Daddy had been reading to us ever since David, Alvin, and I had had to sleep in one bed at the Dixie Hotel in Mammoth Cave, Kentucky, on the drive up to New York. Maybe it seemed sadder because it was a foreign movie, and I had never seen one. And there was something unbearably

sad about the newspaper ad for Bicycle Thief , which showed the little boy on the left and said, "Please don't let them cut me out of . . . " above the title, and below it, "The prize picture they want to censor! Exclusive showing now! Uncensored version . . . 7th month."

But we saw Destination Moon instead. It was roughly five years before I developed an exclusive taste for reading science fiction and six years before I sold a one-page story about time travel to Anthony Boucher at the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction . And, all things considered, I enjoyed the show—particularly Dick Wessen, who was funny, and jumping up and down on the moon like a rabbit, which was fun and funny too.

For many people, the ultimate praise for a movie is that it's realistic, believable, real. In fact, this praise doesn't mean that the movie is realistic/believable/real but that the movie supposedly proves that some aspect of one's life is realistic/believable/real, ostensibly by duplicating it. Yep, there are more false assumptions here than you can shake a stick at. But it sells lots of tickets, writes lots of reviews, wins lots of prizes, finances lots of movies. So who cares what's real or true, as long as it keeps you in business?

Don't you know a book like this can be imagined, discovered, written, or read only within a privileged dream bubble that most people can't even begin to afford, a real-life movie in which there are always other people to carry most of the props? What is it that gives Stanley and me such charmed existences as we walk through life perpetually losing and rediscovering keys, wallets, books, memories, ideas? Not that we always find them again; today, May 19, 1979, I lost my wallet for the second time this year. The last time was four months ago, in a cab, and the next rider in the cab found the wallet, phoned me the next day, and returned it with everything intact. This time I don't expect to get it back. I lost it somewhere between the cash register at New Morning Bookstore on Spring Street and the table where I had lunch at the Cupping Place on West Broadway, a block and a half away, and, helpless as M. Hulot, I have no idea what happened to it.

A Note on Temporary Structures

Did you ever see the Central Park Casino in New York? During my college days it was the fabulous night club where Eddie Duchin played the piano. It was torn down in 1940. The site is now known as Mother Goose Playground and the area is restricted to children under 14.

The Central Park Casino was rebuilt—in New York's Central Park, near the original spot—in order to make this picture. Don't look for it when you go to New York; it was a temporary structure, and was taken down after the filming of the picture was completed.

"The Eddie Duchin Story," starring Tyrone Power and Kim Novak, opens today at the Shoals. It's in CinemaScope, Technicolor and stereophonic sound.

—Stanley Rosenbaum's Sunday column, Florence Times, October 14, 1956

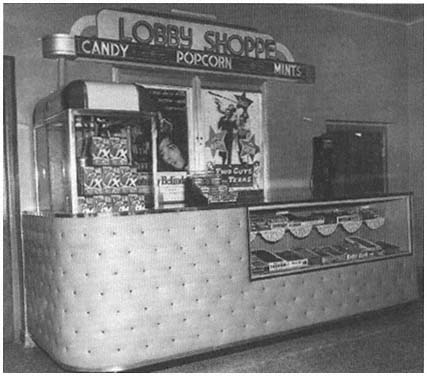

Bobby Stewart liked to do things his own way. The first concession stand at the Shoals, for instance, had that Lobby Shoppe sign not because Bo asked for it but because Bobby decided to put it together on his own and to tell Mr. Rosenbaum about it afterward. When he redid the sign more than ten years later, in the spring of 1959, with lots of cartoon characters like Tom and Jerry and Bugs Bunny on it, it was the same deal exactly: nobody asked him to do it, but he did it just the same.

He came to work for Mr. Rosenbaum (never Louis or Lou) as a sign painter and general utility man in November 1936, in time becoming manager of the Princess, then transferring to the Shoals when it opened a block away, taking along his newly built Lobby Shoppe sign. (Elmo Johnson, manager at the Majestic, assumed his old job.) Over the years Bobby learned more than a thing or two about theater equipment, and during his stint in the service he was responsible for the upkeep of 198 projectors in New Guinea.