1—

"Everybody who cares for his art, seeks the essence of his own technique," said Dziga Vertov.[1] This characteristically modernist "mystique of purity," as Renato Poggioli has called it, pervades the avant-garde tradition and produces the desire "to reduce every work to the intimate laws of its own expressive essence or to the given absolutes of its own genre or means."[2] A typical exponent of the essentialist position was Germaine Dulac, who wrote in 1927, "Painting . . . can create emotion solely through the power of color, sculpture through ordinary volume, architecture through the play of proportions and lines, music through the combination of sounds." Thus, Dulac argued, it is imperative for film artists "to divest cinema of all elements not particular to it, to seek its true essence in the consciousness of movement and of visual rhythms."[3]

Probably the best known among the early candidates for cinema's "true essence" was Louis Delluc's photogénie . Jean Epstein declared, "With the notion of photogénie was born the idea of cinema art."[4] But Epstein also admitted, "One runs into a brick wall trying to define it."[5] The best description Delluc could come up with was, "[A]ll shots and shadows move, are decomposed, or are reconstructed according to the necessities of a powerful orchestration. It is the most perfect example of the equilibrium of photographic elements."[6]

The concept of photogénie simply did not get to the heart of the matter. It directed attention to the image—"the equilibrium of photographic elements"—but not to the properties or "elements" of the image itself. Not, in other words, to the "true essence" of cinema. Other avant-garde filmmakers and critics looked deeper and found cinema's basic principles in three interrelated elements: light, movement, and time.

"For cinema, which is moving, changing, interrelated light, nothing but light, genuine and restless light can be its true setting," said Germaine Dulac.[7] Louis Aragon called cinema "the art of movement and light."[8] And even the leading proponent of photogénie , Louis Delluc, wrote, "Light, above everything else, is the question at issue."[9] Coming closer to the present, we find Jonas Mekas declaring, "Our real material had to do with light, color, movement."[10] Stan Brakhage has called light "the primary medium" of film. "What movie is at basis is the movement of light," he has said. "As an art form really, the basis is the movement of light."[11] For Ernie Gehr, "Film is a variable intensity of light, an internal balance of time, a movement within a given space."[12] According to Michael Snow, "Shaping light and shaping time . . . [are] what you do when you make a film."[13] For Peter Kubelka, "Cinema is the quick projection of light impulses."[14]

Although Kubelka, among others, has insisted that movement is merely an illusion produced by the "quick projection of light impulses," some filmmakers regard movement as, in the words of Slavko Vorkapich, "the fundamental principle of the cinema art: [cinema's] language must be, first of all, a language of motions."[15] In a manifesto in 1922, Dziga Vertov called for "the precise study of movement," and added, "Film work is the art of organizing the necessary movements of objects in space." For Vertov, the recording of moving objects was less important than "organizing" their movement and if necessary "inventing movement of objects in space" through frame-to-frame and shot-to-shot relationships.[16] These relationships—or "intervals" in Vertov's terminology—are temporal as well as spatial. They are the basis of what Snow calls "shaping time." As Maya Deren has put it, "The motion picture, though composed of spatial images, is primarily a time form ."[17]

"Light, color, movement," "the movement of light," "the quick projection of light impulses," "light and time," "a time form"—such phrases reflect the specific interests of individual filmmakers but taken together they specify film's "true essence" in terms appropriate to the avant-garde's "mystique of purity": "light-space-time continuity in the synthe-

sis of motion," in Moholy-Nagy's neat formulation.[18] What is most significant for our present purposes is that the same terms can be applied to visual perception . The basic requirements for seeing are also light, movement, and time. As one researcher has put it, "The eye is basically an instrument for analyzing changes in light flux over time."[19] That succinct statement delineates a common ground for vision and film, and it points the direction I will take in seeking a perceptual basis for the visual aesthetics of avant-garde film.

When we look at the world around us, we do not, as a rule, see "changes in light flux over time." We see solid objects moving and standing still in a well-defined three-dimensional space (at least, that is what we see in the most focused, central area of our vision). Nothing would be visible, however, were it not for the "light flux" entering our eyes through the pupil and flowing over the photosensitive cells lining the back of our eyeballs. Experiments have shown that when the retinal cells receive a steady, unchanging light, when the stimulus is absolutely fixed and unvarying, the cells quickly "tire." They stop sending the information our brain needs to construct the visual world we see lying in front of our eyes.[20] Thus there has to be a "flux," a movement of light over the retinal cells; otherwise, we see nothing at all. (If the sources of light do not move, the eye's own movements will keep the light moving across the cells.) "All eyes are primarily detectors of motion," R. L. Gregory points out, and the motion they detect is of light moving on the retina.[21] Only by these changing patterns of illumination can the world outside our eyes communicate with the visual processes of the brain. From that communication emerges our visual world.

Since light moving in time is the common ground of vision and film, perhaps it was inevitable that avant-garde filmmakers seeking the "true essence" of their medium would hit upon the "essence" of vision as well. Avant-garde filmmakers, especially the filmmakers of the 1920s, did not necessarily make a conscious effort to equate the basic elements of cinema with the basic processes of visual perception. Whether they did so or not, their work has been influenced by an implicit equation between cinema and seeing that this chapter is devoted to making explicit.

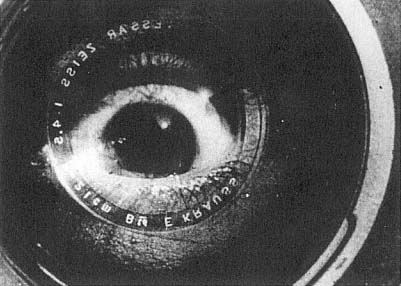

The superimposed eye in the camera lens in Vertov's The Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Man Ray's Emak Bakia (1926) is in fact an explicit depiction of that implicit equation. Less explicit references to the relationship of film and vision occur in many other images of eyes created by avant-garde filmmakers. What Steven Kovaks has called "the leitmotif

of the eye" in Emak Bakia can be traced throughout the history of avant-garde film.[22] To mention a few examples: the infamous sliced eyeball in Un Chien andalou (1928), the photograph of an eye operation in Paul Sharits's T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968), the close-ups of Kiki's eyes in Léger's Ballet mécanique (1924), the oriental eye at the keyhole in Cocteau's Blood of a Poet (1930), the artist's escaped eyeball in Sidney Peterson's The Cage (1947), the Eye of Horus in Kenneth Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954, revised 1966 and 1978) and Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969), and the "cosmic eye" created by swirling clouds of color in several of Jordan Belson's films. To end this potentially endless parade of avant-garde eyes are two especially pertinent examples: the extreme close-up of an eye at the beginning and end of Willard Maas's Geography of the Body (1943) and an eye super-imposed over a reclining woman near the end of Brakhage's Song I (c. 1964).

The eye in Geography of the Body alludes directly to the extremely close and (literally) magnified seeing that is the principal concern of that film—not the voyeur's secret sexual gratification but the explorer's fascination with the human body as terrain seen for the first time.[23] Brakhage's Song I also alludes to visual exploring, or what Brakhage would call the "adventure of perception," which should prompt all filmmaking. The eye in that film, which Guy Davenport has called "an overply, the flesh window," is seen in the world it sees, as it sees the world.[24] The Brakhagean eye is a participant-observer (perhaps the anthropologist rather than the explorer is the appropriate analogue). It refers specifically to the inseparability of seeing and filmmaking—as do Vertov's and Man Ray's images of the eye in the camera lens. As I pointed out in the Introduction, there are significant differences between Brakhage's emphasis on "the flesh window" of the human eye, and Vertov's and Man Ray's emphasis on the "mechanical eye" of the camera. But both make direct reference to the metaphor of the camera-eye and more indirectly to film as (in James Broughton's phrase) "a way of seeing what can be looked at."[25]

To show that film is "a way of seeing," that it resembles visual perception in basic and specific ways, I will reexamine the metaphor of the camera-eye. Visualized directly through the superimposition of eye and camera lens, alluded to indirectly in many other variations on "the leitmotif of the eye," it is a metaphor so intrinsic to the visual aesthetics of avant-garde film that despite (or perhaps because of) its familiarity, it requires close, careful explication.

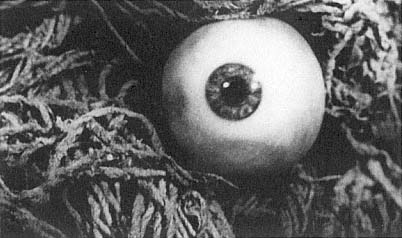

The eye and lens superimposed in

The Man with a Movie Camera

(Dziga Vertov).

The eye replaces the lens in Emak Bakia

(Man Ray).

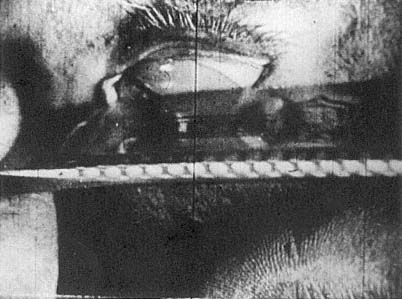

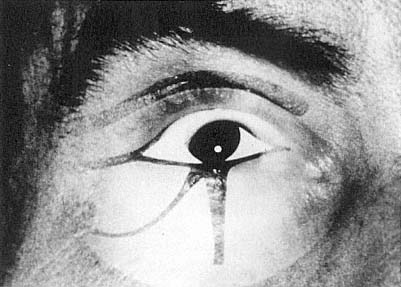

A razor slices the eye in Un Chien andalou

(Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali).

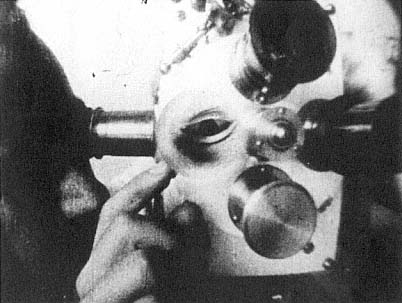

An eye operation in T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G

(Paul Sharits).

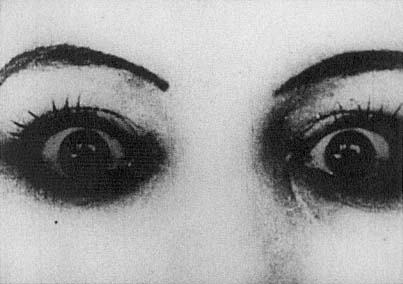

The eyes of Kiki, the Parisian model, in Ballet mécanique

(Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy).

The eye at the keyhole in Blood of a Poet

(Jean Cocteau).

The escaped eyeball of an artist caught in a mop in The Cage

(Sidney Peterson).

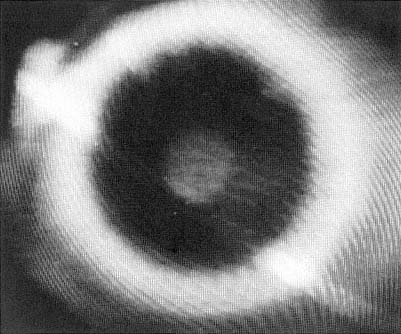

The Egyptian Eye of Horus superimposed on

a human eye in Invocation of My Demon Brother

(Kenneth Anger).

The "cosmic eye" in Infinity

(Jordan Belson, video version).

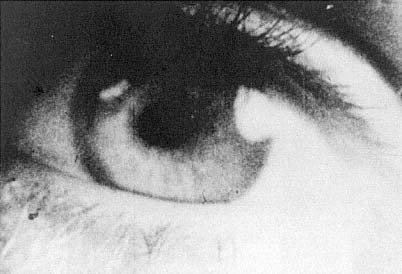

The magnified eye in Geography of the Body

(Willard Maas).

The superimposed eye in Song I

(Stan Brakhage).