Learning from the West

Architectural Theory

Architectural representation at the world's fairs brought a new focus to the discussion of architecture in Islamic countries themselves. Ottomans played leading roles among other Muslim nations, both in architectural practice and in theoretical debate—not a surprising phenomenon, given the independent status of the empire. The Ottoman government hired Europeans as architects and consultants, but not as policy makers. Thus if Western trends were followed in architecture and urban planning, this was the result of a conscious choice by the ruling elite.

Developments in graphic representation techniques and in architectural philosophy during the last three decades of the nineteenth century diverged considerably from the conventions of the classical period. Exhibitions did not cause these changes, but they acted as catalysts by publicizing them—for they were embodied in the pavilions themselves, in architectural drawings displayed at the exhibitions, and in theoretical debates published on these occasions.

The architectural historian Gülru Necipoglu-Kafadar describes Ottoman architectural practice as heavily reliant on detailed plans, often presented in a grid. The standardization and modulation of such a system meant that the imperial style could be rapidly disseminated throughout the provinces. The elevation drawings, however, dependent on the miniature painting tradition, remained schematic and imprecise and did not match the meticulously detailed ground plans.[1] In contrast, European drawings of Islamic monuments from the eighteenth century on presented carefully rendered perspectives, elevations, and sections, as well as plans.[2] These were executed using European

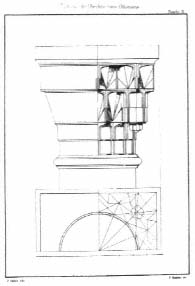

Figure 99.

Detail drawing from Montani Effendi

and Boghos Effendi Chachian,

Usul-u mimari-i Osmani .

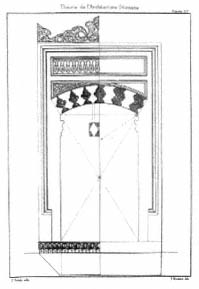

Figure 100.

Detail drawing from Montani Effendi

and Boghos Effendi Chachian, Usul-u

mimari-i Osmani .

techniques of graphic representation, which differed from the Ottoman practices in their rendering of elevations, sections, and perspectives. Detail drawings also belonged to the Western tradition and were introduced to the Ottoman Empire by European architects. The emphasis on Islamic details in Western drawings stemmed from the widespread belief among European architects that the value of Islamic architecture lay in its decorative creativity.[3]

As European architects began practicing in the Ottoman Empire, they brought with them their own graphic traditions, which soon became the norm. For example, when Parvillée was commissioned to work on monuments in Bursa, he documented his surveys with precise plans, elevations, sections, drawings that combined sections and elevations, and drawings of many details. Furthermore, in some of the section-elevation drawings, he indicated the analytical lines demonstrating the rules of geometry he had "discovered" (see Fig. 55). Some of this work, displayed at the 1867 Paris exposition, legitimized the "official" adoption of the graphic techniques (see pp. 96–106).

In Usul-u mimari-i Osmani, or L'Architecture Ottomanae, published by the Ottoman government on the occasion of the 1873 exposition in Vienna (see chapter 2), the drawings by Montani Effendi, Boghos Effendi Chachian, and M. Maillard displayed the same techniques and the same repertoire of plans, sections, elevations, and details, some in color (Figs. 99–100). The book was

based largely on lessons learned from Parvillée's work. Although Usul-u mimari-i Osmani was published one year before Architecture et décoration turques, the introductory essay, with its emphasis on "rules" and "necessary drawings," is not coincidental or original but a continuation of discussions of the science and the "hard facts" of architecture stemming from Parvillée's designs for the 1867 exposition, Anatole de Baudot's analyses of these pavilions the same year, and Parvillée's Architecture et décoration turques, whose foreword was written by Viollet-le-Duc.

The concern for the revival of Ottoman architectural forms in Usul-u mimari-i Osmani did not extend to a search for an Ottoman architectural theory; nineteenth-century Ottoman attempts to interpret local architecture remained anchored to the European way of thinking.[4] Although architectural theory in Islamic cultures is an elusive topic, yet to be studied, certain treatises stand out—among them two classical Ottoman texts that make sporadic references to the philosophical foundations of the discipline. In the biography of the great sixteenth-century architect Sinan, architecture was said to be the work of civilization; the great works of architecture and engineering symbolized the magnificence of the sultan and the state, embodying the height of civilization at the time. The architect was the creator of the civilized environment.[5] Cafer Efendi's early seventeenth-century treatise also attempted to place architecture in a broad context by making an analogy between the creation of the universe and architecture and by discussing the similar roles of harmony, geometry, and proportions in the arts—specifically music and architecture.[6] There was no comparable approach in L'Architecture ottomane or Architecture et décoration turques, which rationalized Ottoman architecture according to geometric and formalistic relationships. Although the first work speculated briefly on the appropriate uses of certain architectural elements, the discussion remained piecemeal.

Necipoglu-Kafadar's recent work emphasizes the geometric rules of classical Ottoman architecture. Although there were no elevation or section drawings in Ottoman practice, Necipoglu-Kafadar claims that elevations were "computed by traditional formulae deriving from proportions inherent in the geometric ground plans with modular grids"—not surprising given that Ottoman architects had a rigorous training in geometry.[7] In this light, Parvillée's analyses appear particularly relevant, even though he avoided cross-references between plans and sections/elevations. Further research may yet prove that his

analyses of Bursa's monuments, focusing on geometric relations and numerical proportions, are more insightful than previously believed.

Architectural Practice

Participation in the world's fairs had an impact on architectural practice in Muslim countries: the search for a representational image in the exposition pavilions enhanced the development of a neo-Islamic style. As we have seen, these countries were concerned to develop an architectural style appropriate to the new age that would also reflect their historical heritage. For Muslim as for Western countries the expositions provided a setting in which to test new ideas. Of course, the buildings themselves were not physically accessible to people at home, but, for example, the extensive information on them in the contemporary Ottoman press suggests their potential as models to be followed at home.

Neo-Islamic style after the 1850s differed from earlier architecture that referred to the Ottoman Empire's classical period, its acknowledged highpoint, as an enduring model. Until then building functions and programs had provided continuity between the monumental architecture of past and present: the building types—mosques; madrasas, or religious schools; hospitals; mausoleums; etc.—had remained the same. In contrast, the neo-Islamic style of the second half of the nineteenth century was applied to new secular building types, adopted from Western precedents: an Islamic architectural vocabulary was used in otherwise Beaux-Arts buildings.[8]

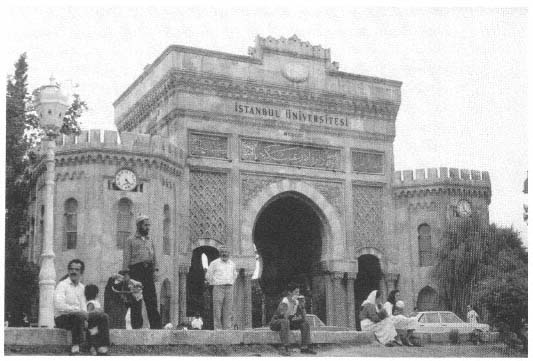

European architects designed the first neo-Islamic buildings in Istanbul, beginning in the 1860s. The early examples were architectural "fragments," like the Moorish-inspired gateway (originally conceived for the Golden Gate of the Theodosius walls) placed at the entrance of the new Ministry of Defense headquarters, now Istanbul University; it lined up neatly with the main gate of the ministry, designed by the French architect Bourgeois, its centrality accentuated by two symmetrical kiosks in a matching style (Fig. 101). The neoclassical military barracks in Taksim had an elaborate gate based on a mixture of "Islamic" styles from different regions (Fig. 102). The Islamic vocabulary of the tripartite portal to Bourgeois and Parvillée's 1863 building for the General Ottoman Exposition in the Istanbul Hippodrome (discussed in chapter 4) also stood out, but here the references were carried out in the facades as well.

The more radical applications of a neo-Islamic style occurred later in the

Figure 101.

Gate of the Ministry of Defense, now Istanbul University (photograph by the author).

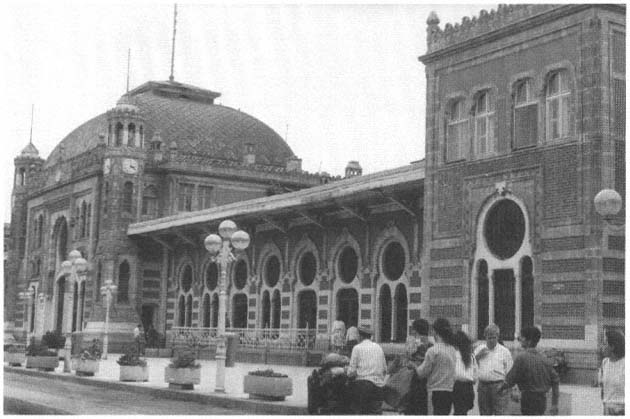

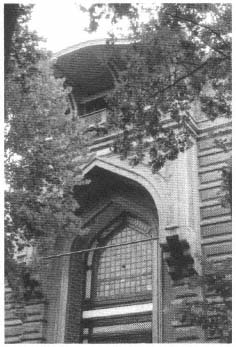

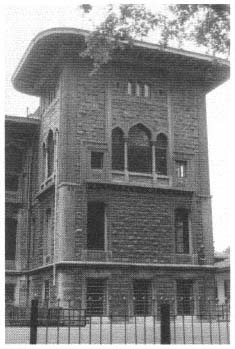

century, most strikingly in two monumental buildings: the 1889 Terminal of the Orient Express (described in chapter 3 with reference to the Ottoman pavilion erected for the 1900 Universal Exposition) and the 1899 Public Debt Administration Building, designed by the French architect Antoine Vallaury (Figs. 103–105). Located prominently on the hill behind the terminal, Vallaury's building combined Beaux-Arts principles with elements of the local chitecture: the large caves and bay windows were borrowed from Turkish houses; the choice of materials, the monumental entrances, and the fenestration echoed certain Ottoman monuments. Unlike the Terminal of the Orient Express, Vallaury's building was an exercise in a purely Turkish-Islamic revivalist style.

The evolution of a neo-Islamic style in Istanbul went hand in hand with architectural experimentation in the Ottoman exposition pavilions. The earlier building "fragments" in the capital—like the gateway to the Ministry of De-

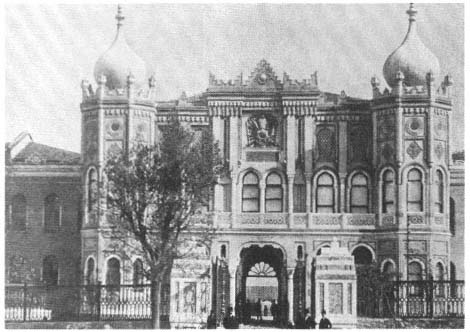

Figure 102.

Gate of the military barracks in Taksim, Istanbul ( Sehbal, 1908).

fense—had the ephemerality of a stage set, perhaps because they stood out on buildings and complexes in otherwise different styles (for example, neo-Islamic portals on a neoclassical structure, as in the military barracks in Taksim). In contrast, the later structures have an imposing permanence, as they confidently integrate the traditional vocabulary into their design. These buildings correspond to such reinterpretations of Islamic architectural forms as those in the Chicago and Paris exposition pavilions in 1893 and 1900.

Cairo's Neo-Arabic Renaissance" (so named by Robert Ilbert and Mercedes Volait) paralleled the architectural developments in the Ottoman capital and originated in a similar concern about the loss of local architectural traditions under the growing influence of Western styles. For example, in 1871 Frantz

Figure 103.

Terminal of the Orient Express, Istanbul (photograph by the author).

Bey warned that the old facades might soon disappear; ten years later it seemed to another commentator that "everything is threatened by the banal transformations which are invading our cities from the West."[9]

In the late nineteenth-century architecture of Cairo and Alexandria, regional features such as corner stalactites, geometric bands defining windows, crenellations, musharabiyya s, and even minarets were used decoratively in public and residential buildings (Fig. 106).[10] But local elements also came into play in fundamental changes of compositional principles. For example, the spatial organization of family functions in the Gazira Palace (built in 1863 by Frantz Bey and Curel) as well as in some villas of the 1870s was based on "a liberal way,

Figure 104.

Public Debt Administration Building,

Istanbul (photograph by the author).

Figure 105.

Public Debt Administration Building,

Istanbul (photograph by the author).

not . . . terrible old traditions";[11] thus in residential quarters the sexes were not rigidly divided.

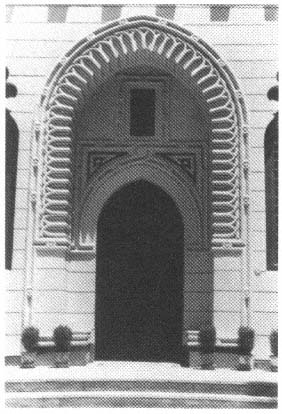

The decorative trend became popular in small-scale buildings, such as single-family residences or apartment buildings, whereas the more radical trend was pursued in larger-scale public projects (for example, in the work of al-Sayyid Mitwalli Effendi, who was in charge of a number of public buildings for the Ministry of Public Works in the 1900s). Some of the intelligentsia, among them Mariette-Bey, claimed that a return to "Moorish decoration" was "childish." Although the theoretical debate, as well as most of the neo-Arabic structures, had been originated by European (French, German, and Italian) ar-

Figure 106.

Entrance to Khayri Bey Palace, Cairo, 1870

(Mimar, no 13, 1984).

chitects, these men received their orders from Westernized Egyptian officials, including 'Ali Mubarak Pasha, Isma'il Pasha's Paris-educated minister of public works—the Haussmann of Cairo. Therefore, while the proponents of neo-Arabism in Egypt were European architects, the style reflected Egyptian social and cultural transformations, especially among the ruling elite and the newly developing "cosmopolitan bourgeoisie" for whom neo-Arabism was "an expression of a search for identity."[12]

This search for identity was rehearsed in the exposition pavilions abroad. In fact, the same men who built the pavilions—among them Mariette-Bey—played leading parts in the construction industry in Egypt. The populist "decorative" approach corresponded to the attempt to represent Egypt truthfully at Western fairs in "streets of Cairo" characterized by irregular outlines, mush-

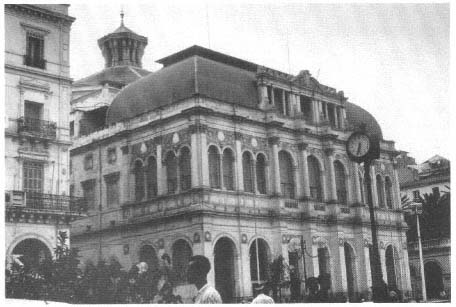

Figure 107.

Theater, Algiers (photograph by the author).

arabiyyas , arabesques, and dirty facades with peeling paint. In contrast, the search for fundamental transformations benefited from the construction of neo-Arabic palaces and okels on the exhibition sites.

The architectural scene in the French colonies of North Africa differed from that in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt. The colonizers in North Africa first expressed their presence and power through a deliberately foreign architecture. From the conquest of Algeria in 1830 to the 1900s, a "neo-classical austerity" dominated,[13] beginning with extensive demolition in Algiers for a large Place d'Armes for military maneuvers and the construction of the first arcaded streets that cut through the lower Casbah.[14]

Although the demolished sections of Algiers were filled with new buildings in the "conqueror's style" (Fig. 107),[15] the French were not indifferent to North Africa's architectural heritage. From 1867 on, they constructed neo-Arabic pavilions to represent the colony at the universal expositions. In such "indigenous" architecture they effectively displayed the wealth and the extent of their imperial power, reserving the neoclassical "conqueror's style" for the Palace of the Ministry of Colonies.

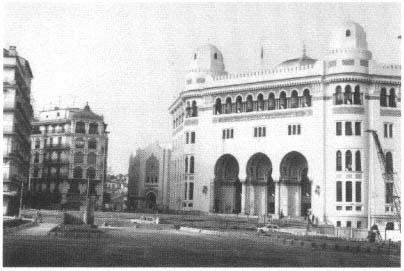

Figure 108.

Central Post Office, Algiers (photograph by the author).

After the turn of the century, as the political agenda shifted from "assimilation" to "association" under the leadership of Algeria's Governor-General Charles Jonnard, French architectural policy in the colonies showed a similar shift, realized in a "spirit of conciliation and tolerance."[16] The official buildings in Algeria, Tunisia, and later Morocco began to quote the local heritage, leading to a new architecture that combined the principles of modernism with highly interpreted historical forms (Fig. 108). The preparatory work for this phenomenon, called arabisance by François Béguin, had already been completed at the world's fairs where architects of the colonial pavilions had interpreted the Islamic architecture of the colonies according to Beaux-Arts principles. During the first decades of the twentieth century, early modernists incorporated the "simple contours and facades" of Arab architecture into their repertoire, creating an architecture of "association" based on the elementary forms, geometric masses, and sparse decoration of France's North African colonies.[17]