3—

Reproductions: Limited Editions, Ready-Made Origins

Fundamentally, I don't believe in the creative function of the artist .

—Marcel Duchamp

Considering the significance of the ready-mades, Arthur Danto reminds us that "Duchamp did not merely raise the question What is Art? but rather Why is something a work of art when something exactly like it is not ?"[1] Danto's reformulation of the classical question "What is Art?" displaces the locus of value from a generic question about art to a specific inquiry about its meaning for the modern period. In the age of mechanical reproduction art can no longer be defined by presuming an essential relation between the uniqueness of objects and the individuality of the producers.[2] The technological reproduction of objects disrupts the referential relation of the artist and the work, as well as a valuative inscription of objects as art objects. In doing so it redefines the notion of value as no longer inherent to the actual production of an object, but rather, as generated through its technical and social reproduction.

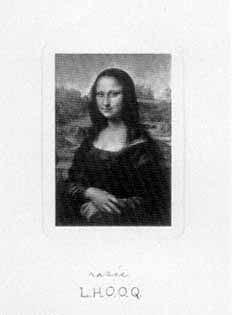

Starting with Duchamp's experiments with the ready-mades, of which Fountain and L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) are the best known examples, we see a consistent effort to explore the effects that mechanical reproduction has on the definition of the work of art. These works deliberately stage the challenge that the reproducibility of objects poses to the work of art, since a new work is created by reactivating the conceptual interval between the original and the reproduction. In doing so Duchamp creates an "interval" or "delay" in the valuative inscription of the work. This

"delay" in establishing how value is vested in an object becomes the conceptual space within which Duchamp experiments speculatively with a new definition of art.

Duchamp, however, is not content to simply explore the impact of mechanical reproduction on the work of art. His project is more expansive, since it includes exploring the speculative potential of the concept of artistic reproduction. As Max Kozloff has noted, the "potentialities of the reproducible" constitute Duchamp's legacy to American art:

The potentialities of the reproducible, in fact, constitute the most over arching of his legacies to recent American art (as well as a story incredibly complex in itself). Doubtless reproduction was a way of demoting the uniqueness of his objects at the same time as promulgating his ideas. His activities here fall into two categories: reincarnations of lost or destroyed objects which are in no sense different from their originals—the bicycle wheel, the urinal; and fac-similes and photographs of his whole production, such as in Box in a Suitcase, which are different scaled reconstructions and records of the original works. All this makes possible, in a burst of brilliant paradox, the coexistence of allusion (to concepts), and literal quotation, of objects.[3]

Kozloff's assessment of Duchamp's contribution identifies the significance of Duchamp's experiments with reproduction and reproducibles. Reproduction functions as a way of "demoting the uniqueness of objects" in order to reactivate them conceptually. This coexistence of allusion to concepts and literal quotation is embodied in the ready-mades, whether it involves the mechanical reproduction of objects, as in the case of Fountain, or the mechanical reproduction of prints, as in the case of L.H.O.O.Q. In this chapter I will explore how mechanical reproduction, accompanied by certain signatory gestures, generates an "original" whose status as multiples challenges the notion of artistic originality. Instead of merely reproducing either ordinary objects or works of art, Duchamp uses these multiples strategically in order to question the meaning of art as a reproductive medium, as well as challenge its artistic limits. While in the process of literalizing the notion of reproduction, Duchamp uncovers in

its reiterative and generative character a creative and speculative potential.

Kozloff also identifies another aspect of reproduction in Duchamp's works, one involving Duchamp's scaled reconstructions of his own work in The Box in a Valise. This work, however, goes far beyond mechanical reproduction, since these objects are carefully handcrafted facsimiles. They cannot be considered to be mere "reincarnations"; that is, objects that are in "no sense different from originals." Are we dealing here simply with "literal quotation of objects," as Kozloff contends, or with "literal quotation," in a "smaller case," as it were? The reduction in scale of the objects and prints in The Box in a Valise adds a tactile dimension to what was previously a visual experience. The tactility of these objects redefines their "literalness" as quotations, since they can no longer be perceived as autonomous objects, but rather as text and texture of an artistic corpus.

Is it sufficient, however, to speak about "literal quotation" in this context? On closer scrutiny, it seems that it is not the object alone that is subject to citation but the artistic medium as well. Given that these are carefully crafted and scaled reconstructions, one can no longer claim that sculpture or painting is being replaced by mechanical reproduction. Quite the contrary, The Box in a Valise represents a concerted effort of artisanal production, where reproduction is no longer limited to mass-produced objects, but applies to Duchamp's entire artistic corpus. In this context reproduction refers both to the relation of art to ordinary objects and to the conventions that define its domain. By actively engaging the spectator in a process of reflection on the limits of artistic representation, Duchamp challenges the traditional definition of painting and sculpture, as media of artistic reproduction.

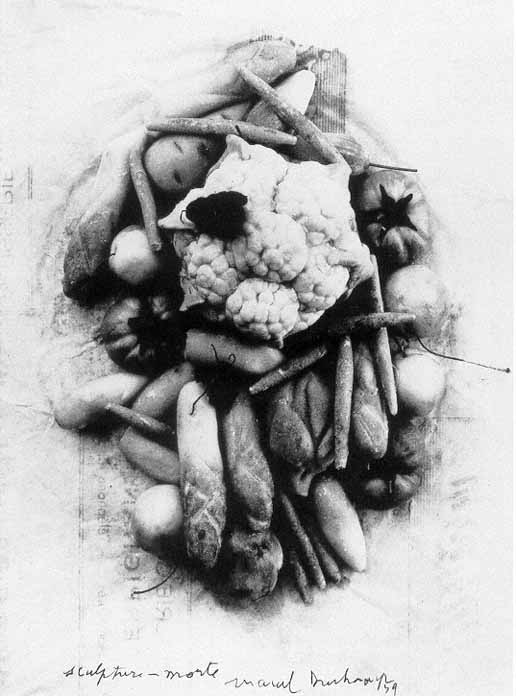

Playing with the notion of artistic reproduction, Duchamp redirects the viewer's gaze from the object to the artistic conventions defining its appearance. Duchamp's effort to highlight artistic convention is visible in a set of later works, TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte —relief sculptures whose exaggerated realism may be considered as proof of Duchamp's return to classical representation. Given their deliberate artificiality and ostentatious evocation of pictorial conventions in a sculptural context, however, these works will be examined as a further elaboration of the notion of the ready-made. Rather than concerning specific objects, the notion of "ready-made" will be applied to the artistic conventions

that govern the production of objects. In this context Duchamp moves away from the notion of mechanical reproduction, only to evoke a related issue, that of the "mechanical" character of artistic production. While Duchamp's ready-mades impel "undeniably real objects to serve as media," works such as TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte constrain the artistic media to the position of objects.[4] Duchamp objectifies painting and sculpture by exposing their "ready-made" character: the conventions that govern their definition as modes of representation. By extending the notion of the "ready-made" from specific objects to artistic modes of production, Duchamp challenges the primacy of mimesis as an artistic origin. This redefinition of artistic production, according to the speculative potential of reproduction, will fundamentally alter the definition of the artist's "creative function."

Reproduction 1: The "Objective" Character of Art

It can no longer be a matter of a plastic Beauty.

—Marcel Duchamp

Among Marcel Duchamp's ready-mades, no object has drawn more interest, controversy, and notoriety than his Fountain (fig. 48).[5] Although Duchamp had been working on ready-mades since 1913, these works were largely relegated to the privacy of his studio.[6] The controversy surrounding the exhibition of Fountain represents the first explicit encounter of the public with the idea of the ready-made.[7] In Fountain an ordinary piece of plumbing—a lavatory urinal—was chosen by Duchamp, rotated ninety degrees on its axis, set on a pedestal, and signed "R. MUTT." Submitted to the first exhibition of the American Society of Independent Artists of April, 1917, Fountain never made it past the deliberations of the hanging jury. Fountain was not exhibited because the jury was unable to recognize the aesthetic value of the work: " [The Fountain ] may be a very useful object in its place, but its place is not an art exhibition, and it is, by no definition, a work of art."[8] Consequently, this scandalous object was "suppressed" (to use Duchamp's term) by being hidden behind a partition for the rest of the exhibition, only to be retrieved later and sold to Walter Arensberg, who lost the piece while it was in his possession.

All that is left of Fountain today is the documentation surrounding a nonevent concerning a nonexisting object: Alfred Stieglitz's (1864–1946)

Fig. 48.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917. (Photograph of lost

original.) Assisted ready-made: urinal turned on its back.

Version of 1964, height 24 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

famous photograph published as the cover to The Blind Man, no. 2 (May 1917), an unsigned editorial entitled "The Richard Mutt Case," and Louise Norton's "Buddha of the Bathroom."[9] There are several full-scale versions of the urinal in existence, whose status as either found objects (they have only an approximate resemblance to the photographic reproduction of the urinal), or as cast facsimiles (full size and miniature size), further modify, through reproduction, the viewer's perception of the lost "original."[10] It is important to note, however, that no subsequent urinal resembles the model photographed by Stieglitz.[11] Renamed the Madonna of the Bathroom, due to a "shadow on the urinal suggesting a veil," this image celebrates an attitude of comic irreverence.[12] The centrality and the sculptural qualities of the urinal are emphasized by its position in front of a painting. By relegating painting to mere background, this bathroom fixture assumes a formal authority that hints at a subjective presence. It is not surprising that Stieglitz's photograph of Fountain is described as looking "like anything from a Madonna to a Buddha."[13]

What is most striking about Fountain is the fact that despite the extraordinary controversies generated by the urinal, the object in question, artistic or otherwise, seems to have barely existed. Initially a mere sample

of mass-produced plumbing, the urinal was further reified through its photographic reproduction, only to come into existence après-coup, as a reproduction that replaces the original. The fact that these authorized and signed belated copies of Fountain are assessed as having significant monetary value further highlights the paradox of a work whose copies are worth more than the original. Fountain , or the drama of the urinal that pretends to be art, thus stages fundamental questions involving the relation of objects to art and value. William Camfield eloquently summarized this dilemma:

Some deny that Fountain is art but believe that it is significant for both the history of art and aesthetics. Others accept it grudgingly as art but deny that it is significant. To complete the circle, some insist that Fountain is neither art nor an object of historical consequence, while a few assert that it is both art and significant—though for utterly incompatible reasons.[14]

Camfield's assessment of the debates about the artistic value or nonvalue of Fountain outlines the impasse generated by this work. It seems that neither the status nor the significance of this object can be decided as long as the challenge that this object proposes to art is not elucidated.

The question regarding the artistic or nonartistic value of Fountain overshadows the fact that this "object" was never displayed. Its scandalous presence is evoked only by the instances of its reproduction, be it photographic or belatedly artisanal. Thus it seems that the value of the urinal is, from the very beginning, tied in with the history of the object's reproduction; that is, with the documentation surrounding the object, rather than the object itself. This emphasis on documentation should not be surprising, once we recognize Duchamp's interest in "a dry conception of art" based on his mechanical interests. Commenting on the Chocolate Grinder, Duchamp explains: "I couldn't go into the haphazard drawing or the paintings, the splashing of paint. I wanted to go back to a completely dry drawing, a dry conception of art. . .< And the mechanical drawing for me was the best form for that dry conception of art" (dmd , 130). His interest in mechanical drawing marks both his radical break with painting and his point of departure for the conceptual developments leading to the

Large Glass; such developments include the use of mechanical renderings, painted studies, and working notations (collected in The Box of 1914 ). Thus, the integration of documentation not merely as a process but as an aspect of the work of art, becomes the trademark of this "dry conception of art." The passage to the ready-mades, that is, the shift from mechanical drawing to an actual mass-produced object, thus emerges as a necessary development. Rather than prescribing the production of an object through mechanical drawing and notation, Duchamp uses documentation as a way of creating a new point of view, "a new thought for that object."[15] The role of documentation now changes: it is neither prescriptive nor descriptive, but rather, poetic. An examination of these poetics will help to elucidate the question of how Duchamp's conception of "dry art" is translated into the "wet art" of the urinal/fountain.

Before exploring this question in more detail, it is important to recall briefly the problems raised by the fact that our knowledge of Fountain is mediated solely through the documentation published in The Blind Man, no. 2. (May 1917). Given that this documentation is not merely a record but also constitutes the only knowledge that we have of this object/event, we must consider what is at stake in this strategy of delayed exposure. The set of displacements that this work actively stages includes: I) an artisanal object replaced by a mass-produced object, 2) an object replaced by a photograph, 3) Duchamp's signature replaced by the pseudonym "R. Mutt," 4) the author (Duchamp) replaced by a photographer (Stieglitz) and a woman writer (Norton), and 5) the spectator (who attends the Independents' Show, but does not see the work) replaced by The Blind Man (a document that publicly exhibits and comments on this work, which was previously not shown).[16] Each of these displacements involves a violation of the traditional criteria defining a work of art: I) the urinal is not an original object, since it is mass-produced, 2) a reproduction (photograph) is exhibited rather than the original, 3) the use of a pseudonym to sign the work raises questions of attribution, 4) it is difficult to attribute the work to a single author, since its reproduction involves other authors, and 5) the spectator does not see the original but knows the work only through its reproduction. In each of these instances one of the terms necessary to the definition of a work of art is displaced, thereby staging the impossibility of classical conditions to define the work as art.

But the history of Fountain does not end here; instead, it continues with the history of its further reproduction through full-scale versions and miniature editions. The reproductions of Fountain are haunted by a technological rather than a human fatality; the urinal chosen by Duchamp in 1917 becomes outdated—its obsolescence being the expression of its technical extinction. Having suffered a "death" of sorts, the object is approximately reassembled in several versions, each different from the other. The Fountain (1950, second version) is selected by Sidney Janis at a flea market in Paris, following Duchamp's request. The Fountain (1963, third version) is based on a urinal selected by Ülf Linde in Stockholm, later approved and re-signed by Duchamp.[17] In these cases the obsolescence of the urinal is compensated for by treating this mass-produced object as a "found" object, and by using intermediaries who act as agents, negotiating its discovery as an "already made" object.[18] There is also a fourth version of Fountain (1964), a cast facsimile edition of eight copies produced by Galleria Schwarz under Duchamp's supervision. In addition there are miniature cast facsimiles for The Box in a Valise, starting with Fountain (1938, a maquette made by Duchamp) and subsequent cast reproductions based on molds, made by different craftsmen (1938, 1940, and 1950).[19] These latter attempts at the reproduction of Fountain, in series of multiples, cannot be considered as "reincarnations of lost and destroyed objects" (as Kozloff contends) but rather as instances mimicking the processes of industrial production.

Thus, the efforts to reproduce Fountain set into motion a veritable industry: an original that is a documented copy leads to the proliferation of copies that are now documented originals. These two disparate gestures both mirror and invert one another. The first gesture involves selecting a mass-produced object and passing it off as art. The second involves the reproduction of a copy in order to produce legitimate art objects, signed by Duchamp. Both conceive the creative act in economic terms, that is, the concept of artistic value in each of these cases is tied to the reproduction of the object. In the first case, the strategy of substitutions operating on the work, the author, and the signature defers systematically the concept of originality by ascribing value not to the object itself but rather to its circulation. In the second case, the reproduction of an object now recognized as art leads to the production of serial works, thereby associating the concept

of value with the production of multiples. The supposed originality of the work of art is subverted by inscribing the work into a relay that corresponds to a set of delays. Artistic value emerges as a function of reproduction, that is, as a process of repetition that postpones the value of the work by inscribing it into the temporality of the future perfect.

If we consider the status of the urinal as a mass-produced object, additional questions arise. What kind of object is the urinal? Can we speak of it as an object in ordinary terms? Because it is mass-produced, Fountain shares with the other ready-mades the fate of being a perfect copy. Its serial reproduction through molds assures the impossibility of distinguishing it from the original; as an industrial object it is a copy with no original, so to speak. In his notes on the infrathin, Duchamp evokes the dilemma of thinking about difference in the context of mass reproduction: "The difference/ (dimensional) between/ 2 mass produced objects/ [from the same mold]/ is an infra thin/when the maximum (?)/precision is/ obtained" (Notes, 18).[20] It seems that the reproduction, and hence, repetition of the object generates an infinitesimal difference making this object more or less similar to itself. As Duchamp explains, "In Time the same object is not the/ same after a I second interval—what/ Relations with the identity principle?" (Notes, 7). By drawing the viewer's attention to the temporal dimension involved in the process of mass production, Duchamp inscribes a delay, an infrathin difference, into its principle of identity. The act of choosing the urinal, or any other ready-made, is based on the assumption that all reproduction involves a temporal dimension mediating the presence of the object. This inscription of a temporal dimension into the perception of the urinal further disrupts the immediacy of the object, just as the title Fountain sets up an incongruence between this ordinary object and the spectator's expectations.

Moreover, not only is the urinal a mold (the same mold that can generate a multitude of analogous objects) but it is also molded to the needs and body of the anonymous spectator. The shape of the urinal follows the dictates of anatomy, but in reverse order. Although it represents the quintessential male instrument, the adaptation of this receptacle to male anatomy generates the potential inscription of femininity, since its visual appearance is that of an oval receptacle.[21] This effort to reproduce the male body by molding the urinal to its shape ironically generates the literal

impression of femininity, its obverse. This double allusion to gender in the guise of femininity and masculinity can be seen as an instance of the infrathin. Duchamp defines this interval as "separation has the 2 senses male and female" (Notes , 9). Thus, eroticism appears in the object where it is least expected to be found—the urinal. It is particularly ironic that eroticism should be potentially inscribed in the gesture associated with the most sterile and precise forms of both corporeal (bodily waste) and industrial production (mass production as the generation of sameness). Reproduction in this context becomes generative, since it recontextualizes both gender and the distinction of ordinary and art objects. The notion of reproduction that Duchamp plays with redefines the nature of the aesthetic object by delaying its becoming an object proper. The interval of this delay, engendered both by the visual appearance of the object and its playful title, becomes the infrathin trace of its libidinal expression.

While Fountain shares with other ready-mades the fate of being a massproduced object, there is a way in which it remains unique. While the choice of ready-mades is based on "visual indifference" and "a total absence of good and bad taste," the urinal stands out because it is difficult to disengage this object from its physical function and its cultural connotations.[22] While Duchamp may ask rhetorically, "A urinal—who would be interested in that?," it is clear that this mass-produced object raises issues that other ready-mades do not. The isolation of this porcelain plumbing fixture on a pedestal evokes, irrevocably, its previous context and history. The urinal is traditionally kept out of sight because of its bodily associations; the evanescent odor of the urinal continues to haunt the metaphorical fountain. The urinal not only is a mass-produced object but it also serves the repeated needs of the masses. The repetition inscribed in the manufactured nature of the urinal is reiterated by its use value, the automatic sense in which it indiscriminately serves the public's bodily needs. Superficially devoid of all artistic connotations, since it is a receptacle for human waste, the urinal activates the potential presence of the male spectator through the pun arroser (to water or sprinkle), thus suggesting the punning coincidence of art and eros (arose ) in a gesture we least expect to associate it with: that of expenditure or waste. Like a lingering smell, the urinal bears the unassailable imprint, the impression of the spectator's body as a negative, and thereby mechanically "draws" in the spectator.

The invisible inscription of this olfactory dimension follows the logic of the infrathin: "smells more infrathin/ than colors" (Notes, 37). Duchamp invokes the olfactory sense in discussing modern art's loss of its "original perfume," its vulgarization when taught according to a "chemical formula": "I believe in the original perfume, but, as all perfume, it evaporates very quickly (after a couple of weeks, or a couple of years maximum); what is left is the dried kernel (noix sechée ) classified by the art historians in the chapter 'history of art.'"[23] Playing on painting as a medium that involves both color and smell (which adds an invisible dimension to painting, like traces of turpentine), Duchamp uses this analogy to comment on the fate of art that has lost its originality. Originality is described as evanescent, precariously inscribed in the work and fleeting like the smell of perfume. The work itself is only the "dry" imprint of a "wet" medium, and thus, ironically, classifiable as art only once it has ceased to exist as a process. This is why smells are more "infrathin" than colors, since the former invoke different sensations at the same time; even as it has ceased to be a liquid through evaporation, perfume lingers as a gas. This may also explain why Duchamp chose the urinal, that is, a mass-manufactured object which, like painting, bears the invisible traces of smell.

Had the viewer missed the olfactory dimension of Fountain as an instance of "dry" art, this allusion is spelled out explicitly in a later work, Beautiful Breath, Veil Water (fig. 49). This empty perfume bottle in a box

Fig. 49.

Marcel Duchamp, Beautiful Breath, Veil Water

(Belle Haleine, Eau DE Voilette), 1921. Assisted

ready-made: perfume bottle bearing label with

photograph of Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy,

height 6 in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Fig. 50.

Book cover designed by Duchamp. Walter Hopps,

Ülf Linde, Arturo Schwarz, Marcel Duchamp:

Readymades, etc., 1913–1964. Paris: Le Terrain

Vague, 1964.

Courtesy of The Menil Collection, Houston.

Fig. 51

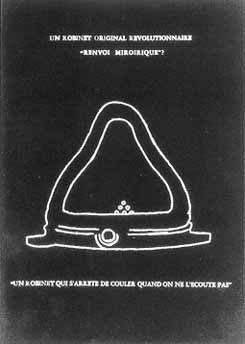

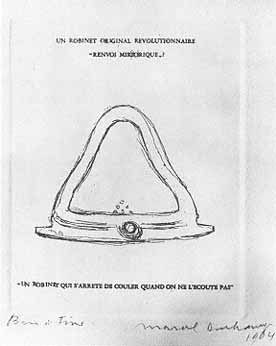

.Marcel Duchamp, Mirrorical Return (Renvoi Miroirique),

1964. Copperplate engraving, 7 1/16 x 5 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Menil Collection, Houston.

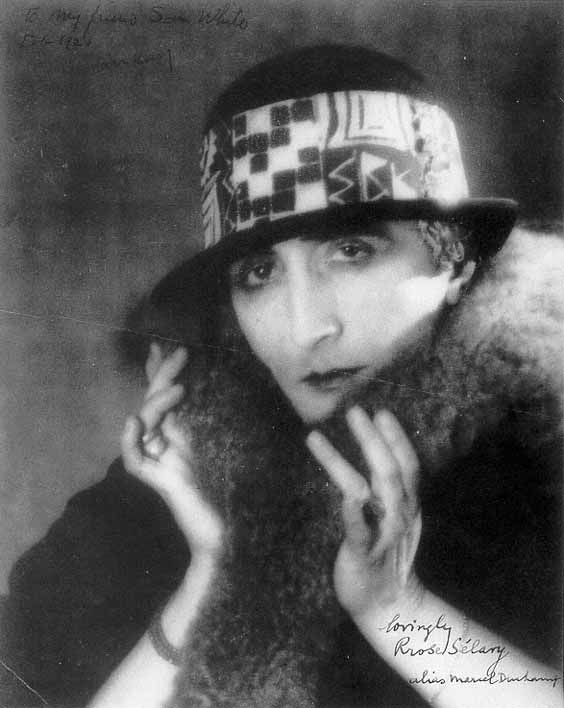

is relabeled with a picture of Duchamp's alias and signature Rrose Sélavy. The work wittily refers back to Fountain literally in disguise, as veiled toilet water (eau de toilette ). Thus the potential inscription of liquid built reversibly in the urinal/fountain is repeated here by the empty perfume bottle, which invokes the absence of liquid by alluding to the perfume (as gas). The toilet water whose female associations are those of veiling or masking bodily odors becomes veiled water (eau de voilette ), a pun on Duchamp's abandonment of painting (as a "wet" medium). This empty bottle, bearing Duchamp's picture travestied as Rrose Sélavy, captures the fragrance of the artist as a seductive woman. Authorship is deessentialized, or rather, reengendered through reproduction. A "female" analogue of the "male" fountain, this work locates artistic originality within the ephemeral scent, the immanence of the "arrhe of painting is feminine in gender"(WMD, 24).

In order to further elucidate the nature of the artistic and gender inversions engendered by Fountain , it is important to consider the mechanism

of verbal and visual puns staged by this work. In 1964 Duchamp produces an ink copy of Stieglitz's photograph of Fountain, on the basis of which he designs a cover for an exhibition catalog, Marcel Duchamp: Ready-mades, etc., 1913–1964 (fig. 50). This cover, which looks like a photographic negative, is later reproduced in an etching that is its positive image, entitled Mirrorical Return (Renvoi miroirique; 1964) (fig. 51). The etching contains three inscriptions: the title "An original revolutionary faucet" (Un robinet original révolutionnaire ); the subtitle "Mirrorical return?" (Renvoi miroirique? ); and a motto, "A faucet which stops running when no one listens to it" (Un robinet qui s'arrête de couler quand on ne l'écoute pas ). Structured as an emblem, the visual and linguistic elements set up a punning interplay that helps us to explore further the mechanisms that Fountain actively stages. On the one hand, there is the mirror-effect of the drawing and the etching, which, although they are almost identical visually, involve an active switch from one artistic medium to the other. On the other hand, there is the internal mirrorical return of the image itself, since this urinal, like the one in 1917, has been rotated ninety degrees. This internal rotation disqualifies the object from its common use as a receptacle, and reactivates its poetic potential as a fountain; that is, as a machine for waterworks. The "splash" generated by Fountain is thus tied to its "mirrorical return," like the faucet in the title.

The predominance of the r 's in the text accompanying the image insinuate the implicit significance of the word art (arh) to the decoding of this image. In other words, the legibility of the image is activated by the pun on "r," [arrhe or art, in French), which, if not articulated, stops working, like the "faucet which stops running when no one listens to it." In other words, Fountain can only make artistic sense when the linguistic faucet is switched on. The word faucet (robinet ) means cock, valve, or tap, and turning the faucet means turning on the waterworks.[24] The punning associations of the faucet bring together all the elements that define Fountain as a Mirrorical Return. These include the "mirrorical return" of art and nonart; the "mirrorical" reproduction and switch from one artistic medium into another; and the notion of gender inscribed as a hinge, a pun that switches back and forth between the male and the female positions. It is not surprising that Duchamp's signature on Fountain, "R. Mutt," which translates literally as "Mongrel Art," is re-signed later (in a

1950 facsimile) by "Rrose Sélavy" (a pun on Eros c'est la vie or arroser la vie), his female alias. Rrose, an anagram of eros, is also a pun on arroser (to water, wet, or sprinkle), a play on the so-called "male" connotations of Fountain.

What initially appears as an instance of Duchamp's conception of "dry" art now emerges as a convincing example of "wet" art. The status of art in this work emerges according to the logic of the "mirrorical return," that is, as a potential mode rather than as an inherent quality.[25] In his notes on the "Infrathin," Duchamp explores the notion of modality:

mode: the active state and not the/ result—the active state giving/ no interest to the result—the result/ being different if the same/ active/ state is repeated. / mode: experiments.—the result not/ to be kept—not presenting any/ interest—(Notes, 26)

Considered as a faucet, the significance of Fountain may be found in its active state as an artistic, erotic, and punning machine. As suggested earlier, the interest of this work is not manifest in its result—its objective character—but rather in the differences produced through the impressions or imprints of the object's reproduction. Fountain is, therefore, an experiment rather than a product, whose interest is purely speculative, insofar as it explores and transforms the boundaries defining a work of art. As an art object, Fountain provisionally hovers at the limits of art and nonart; its existence is purely conditional. The referential meaning of art, as a copy of nature according to good taste, is here eroded through reproduction; a new concept of value emerges through circulation and consumption. The artistic value of Fountain in the age of mechanical reproduction is inseparable from this effort to conceive value in a dynamic, rather than static sense. The erosion of the concept of value as an inherent property of a work of art is transformed by examining the expenditure of value through its circulation and reproduction. The value of Fountain no longer refers to a traditional concept of art but instead to the conditions rendering inseparable the distinction between art and nonart. The "splash" of the Fountain/ urinal creates an active interval, making it impossible to affirm the uniqueness of art without considering the possibility that at any moment it might revert into nonart, like the faucet that

stops running when no one listens to it. As Duchamp explains to Schwarz: "What art is in reality is this missing link, not the links which exist. It's not what you see that is art, art is the gap."[26]

Reproduction 2: The Work of Art as Limited Edition

My landscapes begin where da Vinci's end.

—Marcel Duchamp

The artistic questions raised by Fountain, as an object of mass production, are compounded by Duchamp's explicit use of art prints, reproductions that he "rectifies" with small alterations and signs as works of art. Starting with Pharmacy (Pharmacie; 1914), a commercial print of a winter landscape to which Duchamp adds "two little [red and green] lights in the background" (DMD , 47); followed by Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 3 , a photograph of his painting that is hand colored; culminating with L.H.O.O.Q., a reproduction of Leonardo's Mona Lisa to which Duchamp added a mustache and a goatee; and L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (L.H.O.O.Q. rasée; 1965), a reproduction of the Mona Lisa pasted on an invitation card, there is a succession of reproductions—printed or photographic—that are re-presented as original works of art.

Moreover, beginning with the color plate reproduction of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box; 1934), followed by miniature facsimiles of the urinal (1938–58) and the full-scale versions (1950–64), one can sense Duchamp's deliberate effort to reproduce not only specific works but a sample of his entire artistic corpus, as in the case of The Box in a Valise (1941–68). Pierre Cabanne interprets Duchamp's reproduction of his own works as a sign of his desire to assemble and preserve them as a miniaturized and transportable corpus[27] This hypothesis, however, in no way accounts for Duchamp's systematic experimentation with the concept of artistic reproduction and the questions it poses regarding the "originality" of works of art. Unlike Walter Benjamin, who, in his essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" (1936), questions the impact of mechanical reproduction on the loss of "aura" of the work of art, Duchamp assumes mass reproduction as a given, as the most salient and pervasive manifestation of modernity.[28] The concept of mechanical reproduction becomes for Duchamp a new way of thinking about art, one that treats the "object" as

a series of "impressions," or multiples, in order to redefine the conceptual relation between art and nonart.

Pharmacy (fig. 52) is a commercial color print that Duchamp bought in an art supply store. The only appropriation (or, rather, rectification) that he carries out on this commercially reproduced image is the addition of two identically painted touches of color, red and yellow-green, in the form of three superimposed circles. Duchamp explains that the addition of these two colored lights "resembled a pharmacy" (DMD , 47).[29] Before examining this work in further detail, one must note the impact of Duchamp's recuperation of a commercially available color print, which is available alongside painting supplies in an art store. Is this work the equivalent of painting supplies? In other words, is there a relation between the mass fabricated tubes of paint and this commercial color print? In a talk "Apropos of 'Readymades'" (1961), Duchamp concludes: "Since the tubes of paint used by the artist are manufactured and readymade products, we must conclude that all the paintings in the world are 'ready-mades aided' and also works of assemblage" (WMD, 142). This comment sheds an indirect light on Pharmacy insofar as Duchamp establishes an equivalence between the materials of painting and prints as painterly materials. The fact that they are both mass-produced serves to redefine the nature of the art of painting into works that can be considered as either assisted or reassembled ready-mades.

The title Pharmacy further verifies the hypothesis that this work marks Duchamp's inquiry into the relation between the materials and the art of painting. In Leonardo's time the pigments and the media of painting could be sold only by the Guild of Doctors and Apothecaries.[30] This implicit allusion to Leonardo is not accidental, considering his use of the reproduction of Mona Lisa in L.H.O.O.Q. .[31] Thus, it seems that certain pigments were already made, even during the Renaissance when the artistic and artisanal aspects of painting were considered to be at their height. Duchamp's refusal of color and ultimate abandonment of painting was expressed in terms of his rejection of the visual seduction of painting, as "retinal euphoria" and the "easy splashing way," which entails an aversion to "the cult of the paint itself" and the "intoxication of turpentine." While deploying touches of color, Pharmacy represents an effort to problematize the fetishization with the materials of painting and thus alter the very medium

Fig. 52

Marcel Duchamp, Pharmacy (Pharmacie), 1914. Rectified

ready-made: commercial print of a winter landscape with

two sets of three vertical dots added in gouache, red

and green, alluding to the bottles in a pharmacy window,

10 1/4 x 7 5/8 in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

of painting. It is perhaps not by accident that the conditions of production of Pharmacy on a train, in the half-darkness of dusk, recall Duchamp's earlier experiment in Portrait of Chess Players with painting by a green gaslight. This rejection of daylight is tied to his efforts to discover new tones in painting. "I wanted to see what the changing of colors would do. . . . It was an easy way of getting a lowering of tones, a grisaille" (DMD , 27). In the case of Pharmacy, however, the lowering or graying of tones (grisaille) is already part of the work, since this commercial color print reproduced by printed dots cannot have the brilliance of paint.

Why then does Duchamp add those two touches of red and green, which are, in fact, the only marks of "rectification" of this otherwise banal commercial print? Duchamp's designation of this work as a "Rectified Ready-Made" becomes clearer once we consider its meanings. The word "rectify" comes from the Latin (rectus, right and facere, to make). Its other meanings provide some interesting clues: 1) to correct the

faults in; remove mistakes from; set right; 2) to refine or purify, as liquids, by distillation; 3) to adjust correctly: in electricity, to change from alternating to direct, as an electric current; in mathematics, to find the length of (a curved line).[32] That these various meanings might inflect Pharmacy seems at first remote, if not downright farfetched. As a ready-made, however, Pharmacy seems to be an effort to rehabilitate painting from one of its fundamental conditions: the artisanal intervention of the artist. By analogy to an apothecary, Pharmacy emerges as that original site where the production of pigment, through grinding and distillation, becomes displaced through mass production. This image is rectified at dusk, in the absence of light, while two lights, red and green, are added to the image. The presence of these two lights playfully alludes to color blindness and/or the alternating colors of a semaphore (appropriate to a train or to headlights; a pun on the phares of Pharmacy ).[33] Through this pun, electricity becomes inscribed in the image in an inverted form, as alternating current, rather than direct current.

When asked by Cabanne if this work was an instance of "canned chance," Duchamp agreed, signaling an affiliation between Pharmacy and Three Standard Stoppages. In the latter, three threads one meter in length are dropped. Their curved outline is reproduced by being glued first to canvas, then to glass, and finally, by being reproduced as a wood template. This work thus "cans chance" by destroying the notion of a metric standard and by addressing the mathematical problem of finding the length of a curved line. Analogously, Pharmacy destroys the notion of an aesthetic standard by deploying points of color on a print. The mathematical intervention in this case remains invisible, as long as one does not consider the optical properties of this piece. In fact, as Ülf Linde and Jean Clair suggest, Pharmacy might be Duchamp's earliest experiment with anaglyphic vision, for if the spectator dons red and green glasses, these points coalesce, generating a figure in relief against the blurred background.[34] This stereoscopic effect is explored explicitly in another work, Hand Stereoscopy (1918–19), where two visual pyramids (such as we find in treatises on perspective) come to the foreground when viewed through these special glasses. A third dimension comes into view by its optical projection through color, thereby suggesting that these dots of pigment are the projection of the perspectival (mathematical) principles

underlying optics. This is why, according to Duchamp, "perspective resembles color" (WMD , 87).

This inscription of a potential figurative dimension into a set of colored dots captures the dilemma that confronted Georges Seurat when he did away with the brush in order to construct images from fields of colored dots. The act of viewing a Seurat painting involves a projection of the points of paint into actual figures. This dilemma is alluded to by Duchamp in an early note: "the possible is/ an infra-thin—/ The possibility of several/ tubes of color/ becoming a Seurat is/ the concrete 'explanation'/ of the possible as infra/ thin The possible implying/ the becoming—the passage from/ one to other takes place/ in the infra thin" (Notes, 1). In his interviews Duchamp describes Seurat as the "greatest scientific spirit of the nineteenth century" and as an "artisan" who nevertheless "did not let his hand bother his spirit."[35] As the embodiment of two divergent tendencies—art as a conceptual intervention (matière grise ) and art as an artisanal skill that relies on the hand (patte )—Seurat's work exemplifies the dilemma that painting poses for Duchamp.[36] This dilemma is reenacted in Pharmacy, to the extent that the presence of red and green dots inscribes an allusion to Seurat's pointillist technique, suggesting the possibility of the tubes of color "becoming a Seurat." At the same time, this implied passage (ready-made, in a sense) from paint to painting also introduces the possibility of conceptualizing this relation. The effort to tone down color (grisaille) diminishes color's material centrality to the art of painting by privileging the matière grise, in this context, literally the "gray matter," and the grayness of the commercial print. As a transitional object between paint and painting, Pharmacy rectifies the dominance of art through the repetitious logic of the ready-made. What appears initially as an act of reproduction now emerges in a new sense, as an act of production based on a new concept of materiality that combines the materials of painting with painting understood as conceptual material.

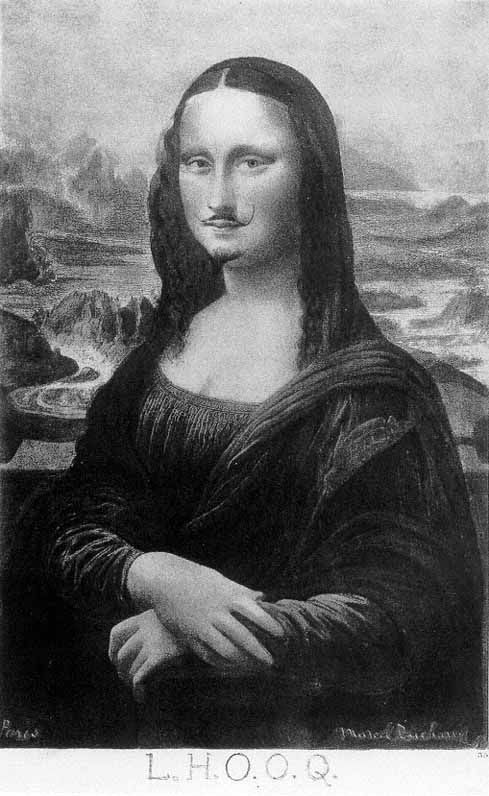

This gesture is repeated in a new way in L.H.O.O.Q. (fig. 53), Duchamp's infamous appropriation of Leonardo's Mona Lisa (which is also known as La Gioconda ). Instead of choosing an ordinary reproduction, Duchamp selected a work that is identified with all that is sacred and beautiful in art. By disfiguring this idealized image through the graffitilike addition of a mustache and a goatee, Duchamp attacks both the

Fig. 53

.Marcel Duchamp, replica of L.H.O.O.Q., 1919, from Box in a Valise (Boîte En Valise), 1941–42.

Rectified ready-made: reproduction of the Mona Lisa to which Duchamp has added a moustache

and beard in pencil, 7 3/4 x 4 7/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

painting's "aura" and its cult value in the history of art.[37] Walter Benjamin observes the danger that the work of art incurs in the age of mechanical reproduction:

That which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of a work of art . . . the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of the tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence.[38]

For Benjamin, the "uniqueness of a work of art is inseparable from being embedded in the fabric of tradition." His statement affirms the cult value of art as defined by the "contextual integration of art in tradition."[39] By using a commercial print of a masterpiece, Duchamp does in fact remove it from the painterly tradition, since the plurality of the reproduction challenges the uniqueness and originality of the work. This gesture, however, merely reiterates the manner in which works of art are removed from their original location in order to be amassed under the institutional authority of the museum. The decontextualization that takes place through the reproduction of a work of art is but the extension of the decontextualization that the museum performs on works of art as it makes them readily accessible for viewing by a mass public.

As Benjamin points out, in the modern age the "exhibition value" of the work supersedes the "cult value" of art. Insofar as artistic production begins with ceremonial objects, the value of these objects is defined by their "existence, not their being on view."[40] The fact, however, that in a museum all objects are displayed equally tends already to destroy the specificity of particular works of art. As Duchamp observes, the act of viewing involves an interchange between the spectator and the work that is minimized by the conditions of display of the object:

The exchange between what one/ puts on view [the whole/setting up to put on view (all areas)]/ and the glacial regard of the public (which sees and/forgets immediately)/ Very often/ this exchange has the value/ of an infra thin separation/ (meaning that the more/ a thing is admired/ and looked at the less there is an inf. t./ sep). (Notes, 10)

In the context of the museum where everything is on display, the display determines the act of seeing. The regard of the public becomes "glacial," to the extent that admiration of a work of art supplants its visibility, obviating the conventions and criteria that define it.[41] The eyes of the spectator become "glazed," as "seeing" in this context means "forgetting." Public regard is conceived of in terms of an exchange whose value is described by Duchamp through the notion of the "infrathin," which he compares to an "allegory of forgetting" (Notes, 1). What is being forgotten in the popularization of art is the fact that value is neither acquired nor inherited; rather, value belongs to the possibility of an exchange between the spectator and the work.

By actively posing the question of popularization through the notion of reproduction, L.H.O.O.Q. reactivates the question of value and its relation to a work of art. This joke on the Gioconda emerges as a commentary on a punning reading of L.H.O.O.Q. as "LOOK," that is, the "infrathin" separation or interval inscribed into the gaze that constitutes the work.[42] The addition of the mustache and the goatee to this smiling and impassive image of the Mona Lisa exposes the fragility of the viewer's gaze, the ease with which this embodiment of feminine ideals can switch gender and thus inscribe a masculine dimension into the image. Although the title L.H.O.O.Q. can be read as the French slur, "she has a hot ass" (elle a chaud au cul ), this vulgar reference to feminine desire is undermined by the masculine "hair," or rather "air," of the image. This vulgarization of an image, whose impact relies on the lack of expression and an ambiguous smile, is due to a con joke on Gioconda, the falsification of its pictorial intent. Not only is the spectator conned by a reproduction but the potential androgyny of this figure suggests that the original itself may be a con job.

Leonardo's Mona Lisa is a portrait with no referent, because this image has never been definitively identified with a particular historical persona. Possible identifications vary, including people such as Isabella d'Este and the wife of a merchant named Giocondo, whose portrait was painted by Leonardo and whose name can be construed as a pun on playfulness (gioco, in Italian).[43] Although Isabella d'Este was known as a practical joker, a detail that might explain the peculiar turn of her smile, in the end there is no evidence clearly indicating the identity of the model of this enigmatic portrait.[44] In addition to the inconclusive nature of the paint-

ing's double title, recent computer studies suggest that this portrait might in fact be a self-portrait, inverted as if in a mirror.[45] Given Leonardo's penchant for inverting his handwriting by writing from right to left, a "mirrorical turn," it would not be surprising that this visual representation of himself might take such a turn. This act of optical transvestism inscribes a fundamental ambiguity into the image, an ambiguity that, ironically, has traditionally been interpreted as the ultimate sign of femininity: Mona Lisa (La Gioconda ) as la prima donna del mondo.

Duchamp's own playful joke on this portrait appears less as a gesture of desecration and violation than as the perpetuation of a long-standing artistic joke.[46] The discrete, delicately penciled-in mustache and goatee inscribe into the image the masculine referent that heretofore had disguised itself in the ambiguity of an optical illusion. The mustache and the goatee return this missing dimension to the image. As Duchamp observes: "The curious thing about that mustache and goatee is that when you look at it the Mona Lisa becomes a man. It is not a woman disguised as a man; it is a real man, and that was my discovery without realizing it at the time" (emphasis added).[47] The mustache and goatee function as a playful index both of Leonardo's "mirrorical turn" and of Duchamp's repetition and rectification of this gesture as a "mirrorical return."

In a work entitled Moustache and Beard of L.H.O.O.Q. (1941), which is a drawing made as a frontispiece for a poem by George Hugnet (1906–1974), entitled Marcel Duchamp (8 November 1939), the mustache and beard are presented by themselves, accompanied by Duchamp's signature. These two elements marking Duchamp's appropriation of Leonardo's Mona Lisa and functioning as his visual signature become decontextualized and reassembled, as it were, under Duchamp's own signature, but as an illustration for a volume whose author is Hugnet and whose subject matter is Duchamp. Thus, the effort to equate Duchamp's visual and written signature is undermined by a relay of signification, making it impossible to locate the precise author. As insignias of Duchamp's appropriation, the mustache and goatee emerge as false indexes of the author. Like theatrical props, they appear as objects for disguise or travesty, rather than as means for designating and legitimizing the authorial gesture. Moustache and Beard of L.H.O.O.Q. problematizes the gesture of artistic appropriation, insofar as it transitively designates the artist, en passant.

Thus neither L.H.O.O.Q. nor Moustache and Beard of L.H.O.O.Q. amount to a portrait, that is, the original act of creating a likeness, of a person either in pictures or in words. Instead, the portrait functions here in the literal sense of pour and traire (forth and draw); that is, as a drawing forth of several images (imprints) from what appears to be a single image. While trait may be interpreted to mean characteristic touch (as in trait of character), it can also mean stroke of genius or of witticism, as well as currency, a bank bill, or draft. Just as the word trait can acquire very different meanings depending on context, so the Mona Lisa, as an image, reveals itself as a repository not only of different but even of mutually exclusive images. The effort to appropriate Leonardo's portrait Mona Lisa, literally results in milking (traire ) this masterpiece. By using a reproduction of Mona Lisa, Duchamp draws forth other likenesses (appearances) that only jokingly recapture its features. The gesture of portraying is translated, therefore, into a drawing forth of other likenesses that differentially inhabit the same image. This is why the addition of the mustache and beard is not a transgressive gesture of violation or desecration. Duchamp is not negating Leonardo's work; rather, he rediscovers within Leonardo's work a set of gestures that make possible his own appropriation and reinscription of the image.

It should come as no surprise that following L.H.O.O.Q. in 1919, Duchamp inaugurates the birth of his female artistic alter ego in Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy (1920–21) (fig. 54). The portrait of the artist as female counterpart is captured by Man Ray's soft-focus picture of Duchamp masquerading as a woman (circa 1920–1921). Signed lovingly by Rrose Sélavy alias Marcel Duchamp, this photograph coyly captures Duchamp's play with the signs defining sexual identity, and by extension, identity in general. As he explains to Cabanne: "In effect I wanted to change my identity, and the first idea that came to me was to take a Jewish name. I was a Catholic, and it was a change to go from one religion to the other . . . suddenly, I had an idea: why not change sex? It was much simpler" (DMD , 64). The artistic pseudonym becomes an elaborate con joke. Rather than dissimulating identity, Duchamp's alias Rrose Sélavy disrupts the notion of artistic identity by reducing it to an arbitrary convention. Identity is reduced to a set of signs and conventions that can be manipulated, so that changing names becomes no more difficult than

Fig. 54.

Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy, 1920–21.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Samuel S. White and Vera White Collection.

Fig. 55.

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (L.H.O.O.Q.,

Rasée), 1965. Ready-made: reproduction of the

Mona Lisa, 3 1/2 x 2 7/16 in., pasted on the invitation

card given on 13 January 1965 on the occasion of the

preview of the Mary Sisler Collection at the Cordier

and Ekstrom Gallery, New York.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

changing religion or sex. In L.H.O.O.Q. the addition of the mustache and beard uncovered the sexual ambiguity of the Mona Lisa, while in the portrait of Rrose Sélavy it is the lack of facial hair that engenders sexual ambiguity. Duchamp's shaved face and discreet smile, generously framed by a fur collar (a punning displacement of facial hair), invokes the illusion of a feminine presence. Like the Mona Lisa, it is precisely the lack of certain signs and the indexical ambiguity of other signs that constructs gender as a riddle. But this riddle functions as a pun or a switch equally designating femininity and masculinity, rather than being construed uniquely as the trademark of the feminine. Thus, it is neither the presence nor the absence of signs that generates gender, but rather their active interplay. In the same way, the question of artistic identity emerges as a game between various personas or positions without a firm referent, but constructed provisionally through their circulation. If Rrose Sélavy is Duchamp's alias (from the Latin meaning at another time), this temporal dimension, or delay, permits us to understand how s/he comes to be Marcel Duchamp at the same time s/he becomes herself.

The relation of portraiture to the artistic persona and the question of the reproducibility of a work of art come to a head in L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved (fig. 55), This work is yet another reproduction of the Mona Lisa, with an added twist: the image has not been altered in any way, other than the title. As Timothy Binkley points out, although this work is restored to its original appearance, it is not restored to its original state. He summarizes Duchamp's intervention as follows:

The first piece makes fun of the Gioconda, the second destroys it in the process of "restoring" it. L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved re-indexes Leonardo's artwork as a derivative of L.H.O.O.Q. , reversing the temporal sequence while literalizing the image, i.e., discharging its aesthetic delights. Seen as "L.H.O.O.Q. shaved," the image is sapped of its artistic/ aesthetic strength—it seems almost vulgar as it tours the world defiled.[48]

The process of "restoring" the Mona Lisa by shaving her does not, as Binkley contends, "destroy" the artistic value of this portrait by merely defiling and vulgarizing this image. Instead, by returning this reproduction to its original status—that of a mere reproduction—Duchamp reveals how the process of reproduction itself fundamentally alters the concept of artistic value. Binkley correctly notes that L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved suggests a reversal of the temporal sequence, making it seem that Leonardo's Mona Lisa would be derivative of L.H.O.O.Q.[49] This apparent dependence of the original on the copy is not entirely fictitious, however, insofar as the spectator's experience of Mona Lisa is, in fact, invariably mediated through its reproduction. The look of the spectator has already been "glazed" over by the reproduction, so that the act of seeing the Mona Lisa is merely an act of conformity, that of verifying the adequacy of the original to its copy. Rather than being a destructive or negative gesture, Duchamp's intervention clarifies the tenuous relation between works of art and their copies. Consequently, L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved does not "sap" this image of its artistic/aesthetic strength, since the artistic value of Mona Lisa hinges on its explicitly ambiguous character. With L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved, we come back full circle to a Mona Lisa that is and is not entirely herself. Duchamp's perpetuation of Leonardo's joke, that is his "mirrorical

return" on Leonardo's "mirrorical turn," restores to the viewer an image that has been reactivated through its interpretations. Rather than "restoring" a painting to his audience, Duchamp restores the concept of painting as a conceptual exercise. By delaying the sensorial impact of paint, L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved as a reproduction inscribes into the perception of the original work an interval reactivating the exchange between the spectator and the work. By seeing the image both as the original and as the reproduction, the spectator discovers the fragile interval separating art from nonart. By switching back and forth between them, the question of value emerges as the correlative of an engagement with the work: an interpretation of art as "making" that demands activity on the part of the artist as well as the spectator. Thus, the notion of artistic value emerges as an index not of the work but instead of the exchanges that it can generate between work and spectator.

Now we can begin to understand what Duchamp meant when he

Fig. 56.

Marcel Duchamp, Still-Torture (Torture-Morte),

1959. Sculpture of painted plaster and flies

with paper background on wood, 11 5/8 x 5 1/4 x

2 1/4 in. Centre national d'art et culture Georges

Pompidou, Paris.

Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

claimed that "The onlookers make the picture," or as he explained in his talk "The Creative Act" (1957): "All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act" (WMD, 140). By ascribing to the spectator the creative role of bringing the work into contact with the external world through a process of interpretation, Duchamp contextualizes the authority of the creative act. This process of contextualization is made explicit in The Box in a Valise, which replaces the museum's authority as an institution mediating our perception of art, with a valise, a portable "museum" in miniature. The spectator unpacks this valise on a table and unloads its contents manually, thereby not merely bringing these miniature reproductions into contact with the world but making these works part and parcel of the world.

Reproduction 3: A Critique of Mimesis

The Possible without the/ slightest grain of ethics of aesthetics / and of metaphysics—

—Marcel Duchamp

In a letter to Alfred Stieglitz (22 May 1922) Duchamp, having noted photography's displacement of painting, suggests that photography itself may one day be replaced: "You know exactly how I feel about photography. I would like to see it make people despise painting until something else will make photography unbearable" (WMD , 165). By 1922, the success of photography as a medium of mechanical reproduction was already challenged by the emergence of other media, such as cinema. Photography's "fidelity" and "originality" as artistic reproduction, however, will eventually face the greater challenge of its mass reproduction and circulation in print.[50] Thus, while photography calls into question the autonomy of painting as a medium for artistic reproduction, it may fall victim to the reproductive technology that first made it possible.

It is this particular "fatality" of an artistic medium, its vulnerability to technical conditions, that fascinates Duchamp, particularly with regard to painting and sculpture. The viability and legitimacy of these media, identified with classical conceptions of art, are at stake in Duchamp's exploration of their putative "end," or rather, "death." In a set of related works, TORTURE-MORTE (fig. 56) and sculpture-morte (fig. 57), Duchamp

Fig. 57

Marcel Duchamp, Sculpture-Morte, 1959. Marzipan Sculpture and Insects, 13 1/4 x 8-/8 x 3 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection

proceeds to explore the concept of artistic reproduction, no longer literally, as in the case of the ready-mades, but as a figurative strategy. These works are handmade originals reproducing traditional pictorial or sculptural subjects with a twist. The plaster cast imprint of the foot and the marzipan sculpture of vegetables capture more than the mere likeness of objects. They mimic the material properties of the sculptural medium, either by erasing the distinction between the model and the rendering (the plaster cast), or by using materials such as marzipan, whose edible character reveals its material affinity to its subject matter—vegetables. If these works haunt the spectator, they do so by breaking down, through reproduction, the formal and material distinctions defining art as a mimetic medium. Rather than marking Duchamp's return to figurative art, these "excessively" realistic works emerge as parodies of the conventions that define it as such.

The titles of these two works suggest a series of puns based on the still life (nature morte, ) one of the major traditions in the history of painting. In both works, however, the word nature has been replaced by either torture or sculpture, indicating that the mimetic representation of nature, which constitutes the genre of still-life painting (nature morte, ) is here elided and taken literally to mean dead (morte. ) In other words, these works stage the death of painting and sculpture both literally and figuratively. These works are particularly troubling because they use mimetic genres destined to portray the illusion of nature as "alive" by depicting a double death: that of the subject of art and its modes of representation. While TORTURE-MORTE depicts the plaster instep of a foot in relief with flies on it, sculpture-morte presents an equally disturbing portrait, a vegetable still life made from marzipan with insects on it. In these works the presence of insects as emblems of decomposition inscribes a disturbing allusion to death into the already "stilled life" or "death" of the image.

George Bauer interprets TORTURE-MORTE as a footnote to the writing of art history, since it embodies Duchamp's literal step enacting the slippery passage from painting to sculpture: "The slip from painting to sculpture relies on the absent piédestal, now replaced by letters that support the work of pun, pain and paint in the essential lay-over of different media and difference in language, art, and letters."[51] The image of the instep of the foot (pas, ) becomes for him an index of Duchamp's antiaesthetic position,

a faux-pas. This faux-pas, however, embodies Duchamp's stumble or misstep over traditional art, since it acts as a metonymic relay that transitively connects seemingly disparate artistic domains. While we may see TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte as "Ironic concessions to/ still lives" (Notes, 107), the irony in question turns out to be a very profound reflection on the limits of sculpture and painting as forms of visual representation. What makes these works particularly difficult to interpret is their deadpan realism and dead-end illusionism. If the ready-made disenfranchised the object by being the object itself, here, the plaster cast of the foot and the legumes represent yet another step forward. Whereas the ready-made was an ordinary mass-produced object that had been nominated as an art object because of its lack of aesthetic value, in this case, we have seemingly legitimate art subjects or objects—pictorial still lifes—which are derealized through their punning relation to both sculpture and language. These works represent yet another interpretation of the ready-made, insofar as they play with the concept of art as a medium for mimetic reproduction.

The insects, which are the incestuous element in these two works, do not make them any easier to swallow, for their presence functions as the exclamation mark of all artistic reproduction: they are the touch of the real, glued or tacked on as a false index.[52] In other words, the flies on both TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte become derealized, since paradoxically their being "real" or the "thing-itself" undermines their aesthetic referential function as mimetic allusions to reality. Hence, these works stage the death of painting and sculpture by renouncing the mimetic function of art only to literalize its conventions. Here, mimesis, as a set of conventions governing the modalities of artistic production, comes to an untimely, almost tragicomic end. For these works mimic the notion of mimesis by reproducing this process literally, thus reducing it to a set of nonsensical puns, TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte. Death (morte ) in this context becomes a reflection on traditional art, its "still" or "dead" character, through which it attempts to create the illusion of "life" in art. The illusion of life sustained by mimetic traditions is expended here, in order to question the fictitious immortality and durability of artistic artifacts. In both of these cases the concept of art as that which exceeds the confines of history is radically redefined through an inquiry into the historicity of all artistic production.

Duchamp's assessment, his pronouncement that pictures, as well as men, are mortal, captures most vividly the shared destiny of humanity and its artifacts:

I think painting dies, you understand. After forty or fifty years a picture dies because its freshness disappears. Sculpture also dies. . . . I think a picture dies after a few years like the man who painted it. Afterward it's called the history of art. . . . Men are mortal, pictures too. The history of art is something very different from aesthetics. (DMD , 67)

The "mortality" of painting and sculpture in this context does not simply imply the historical end of these artistic domains. Rather, as in TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte, it refers to the fact that conventions of artistic production may change or become outmoded—a "death" of sorts. If it is true, as Duchamp contends, that paintings can lose their freshness and visual impact, such a loss would merely be symptomatic of a larger problem. As he further explains, this tendency is merely one aspect of a larger problem involving the historical preservation of artworks within the institution of the museum. The works of art that "survive" are often not necessarily the best works of a particular epoch. Instead, they reflect the conventions of taste of that particular period, which may be quite different from our own. Thus, a work of art may "die" simply because it has failed to be recognized. This is why Duchamp makes the philosophical distinction between aesthetics and art history. The fact that both painting and sculpture have begun to decompose and thus to smell, as testified by the flies on TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte, signifies the incapacity of the visual to sustain itself without a conceptual context. Thus, for Duchamp, the gesture of continuing to paint or to sculpt becomes obscene and obsolete, like torturing the dead.

Given this artistic dilemma, Duchamp's solution in sculpture-morte is particularly ingenious. In his interview with Cabanne he explains that his mother was a painter of still lifes and that she "wanted to cook them too, but in all her seventy years she never got around to it" (DMD , 20). Sculpture-morte thus represents the legacy of an artistic heritage, starting with Arcimboldo's renowned "vegetable portraits," until Duchamp final-

ly gets around to "cooking" his mother's still lifes, that is, turning the raw materials of painting (crudités ) into a baked marzipan sculpture. The shapes of these vegetables, however, are sufficiently ambiguous to also punningly allude to brain outcroppings or cold cuts (cervellités, in French). This wordplay is made possible in sculpture-morte by the outline of a head in the creased paper, where the vegetables (crudités, in French) resemble cooked, "debrained" (cervellités ) outcroppings of the imagination: food for thought, one might say.[53] Thus, Duchamp's representation of the crisis of art for modernity becomes a footnote or foodnote: a lame joke running through a plaster cast foot or a half-baked marzipan sculpture.

Despite their cryptic and cryptlike character, both TORTURE-MORTE and sculpture-morte inscribe, through their visual and linguistic puns, the evanescent perfume of the living artist, who likes "living, breathing, better than working" (DMD , 72,). In sculpture-morte the inscription of Duchamp's signature is present as an unexpected visual pun. The unreal rosy tint that is painted on the work, illuminating it as a gaze or as a gas (an exhalation), marks the presence of Duchamp's artistic alter egos: Rrose Sélavy, alias Marcel Duchamp, alias Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette —all con artists of the art of breathing, heavy and otherwise. In this image aspiration and inspiration come together in the pun of respiration marking, through this fragile hinge, the lingering breath of the artist, the odor of the man whose epitaph appropriately reads:"And Besides/It's Always The Others That Die."

Built on the strategic manipulation of linguistic and visual puns, Duchamp's artistic project emerges as an ephemeral pun on whose nonsensical appearance hinges the facticity of life: "Therefore, if you wish, my art would be that of the living: each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral. It's a sort of constant euphoria" (DMD , 72). Duchamp's self-definition as an artist, "I am a breather" (je suis un respirateur ), summarizes the peculiar coincidence of art, chance, and life in his work. His description of his artistic identity as a "breather" captures the "mechanical" character of this gesture, as well as its "creative" function, since it animates and sustains life. Duchamp's "art of the living" is at the same time a "breath" and a "work," whose meaning is derived from its lack of inscription in a specific domain, be it visual

or cerebral. As an evanescent index of Duchamp's art, it explains how his works hover between the visual, linguistic, and conceptual, without being identified exclusively with any particular artistic domain.[54]

This euphoria attached to the "art of living" is like the infinitely joyful field (champ, in French, and an allusion to his own name) that Duchamp finds right at hand through puns. The pleasure that he takes in nonsense is that of discovering himself in a punning game that eroticizes intelligence:

Tradition is the great misleader because it's too easy to follow what has already been done—even though you may think you're giving it a kick. I was really trying to invent, instead of merely expressing myself. I was never interested in looking at myself in an aesthetic mirror. My intention was always to get away from myself, though I knew perfectly well that I was using myself. Call it a little game between "I" and "me."[55]

Duchamp's refusal to identify himself with previous artistic traditions, and even his own artistic corpus, reflects his claim: "I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own taste." The aesthetic mirror whose reflection Duchamp eschews involves the interpretation of art as a medium for expression, rather than invention. Through analogy to puns, his artistic identity emerges as a creative movement engendered by the interplay of his aliases: a strategic chess game played by con men. This position is made visually explicit in a photographic self-portrait Photograph of Marcel Duchamp Taken with a Hinged Mirror (1917) (fig. 58). In this photograph the referential position of the artist as model is elided; facing multiple reflections of himself, Duchamp has his back to the camera. His visual identity is both supplanted and refracted by a hinged mirror dividing him from himself while multiplying his reflections. This game, by which Duchamp refuses to assume a stable identity as an artist, marks the kinetic and hence, erotic, character of his work. Playing the ready-made field, among "I" and "me," Duchamp discovers "antiart": a game that eschews any specular reduction, since it is governed by the generative power of nonsense.

If Duchamp rejects the conventional notion of artistic creativity—"fundamentally, I don't believe in the creative function of the artist"

(DMD , 16)—this refusal reflects his understanding of art in terms of its Sanskrit etymology, which signifies "making." Visual and linguistic puns are already "made"—they exist as a field of associations to be called upon, reassembled, or made anew, not to be created. Hence the creative originality of the artist is defined in terms of the conceptual operations that are exercised in a field that is always already ready-made. Duchamp's claim that "art has no biological source" (DMD , 100) must be understood as a rejection of the traditional concept of art, which defines originality as the power of the artist to create something totally new, ex nihilo. This is why Duchamp describes the artist as a craftsman, a chess player, or a waiter, that is, as someone whose creativity is transitive rather than originary. If the artist can never create from scratch, this is because s/he functions as a relay, or even a delay. In other words, the artist becomes a "hinge," strategically transporting and transposing the ideas of others in a kinetic exercise that does not foreclose either artistic identity or artistic production. Rather than considering this condition of the artist as a "predicament," Duchamp treats it as a necessary given. He redefines the notion of biological creation as an origin through the strategic evocation of the ready-made: "So man can never expect to start from

Fig. 58.

Marcel Duchamp, Photograph of Marcel Duchamp taken with a hinged mirror, New York, 10 October

1917. From Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp, trans. George Heard Hamilton. New York: Grove, 1959.

scratch; he must start from ready-made things like even his own mother and father."[56]

Duchamp's strategic use of reproduction, ranging from ready-mades to prints, culminates in his parodies of painting and sculpture as artistic media. Along the way, Duchamp succeeds in challenging both the notion of the art object and the objective character of art. What is remarkable about Duchamp's interventions is the fact that they do not represent a negation or rejection of artistic traditions. Rather, they represent Duchamp's speculative exploration of the conceptual potential of art as a medium whose meaning hinges on the manipulation of appearance. Art as the creation of "appearances of appearances" is believed to be the task of art, ever since it was defined by Plato.[57] Yet, the interpretation of art as the imitation of nature is qualified during the Renaissance by the allowance that it need not involve literal reproduction.[58] Duchamp deliberately returns to the notion of literal reproduction in order to explore its poetic and philosophical potential. Whether by using actual ready-mades, or by using artistic conventions as ready-mades, Duchamp redefines art as a strategic medium, and the artist as a transitional figure whose role is to restage both the terms and the conventions defining artistic practice.