Stable Angina Pectoris

Angina pectoris is the classical earmark of coronary-artery disease. Stable angina pectoris, a chronic state, can persist unchanged for years. It indicates that a patient with reduced coronary reserve has no symptoms at rest, but during exercise or activities the amount of oxygen supplied to the heart by the coronary circulation may become insufficient to cover the increased demands. The threshold for provoking chest pain may be constant (that is, the same amount of exercise may always produce pain), but often the appearance of chest pain is contingent on an additional factor, such as walking in cold weather or having eaten a heavy meal. Some patients develop angina in response to excitement or anger. Since in stable angina pectoris a provoking factor is responsible for chest pain, a careful analysis of the circumstances leading up to the appearance of pain is vital. For example, an attack of chest pain at night may prove to have followed a nightmare and thus have been provoked. By contrast, unprovoked nocturnal pain is a sign of unstable angina.

Chest pain in stable angina subsides with rest or disappears promptly when the patient takes sublingually a tablet of nitroglycerin. The effect of stable angina on the life-style of patients varies greatly. Mild angina may be controlled without medication by eliminating strenuous exercise. When anginal attacks begin to interfere with ordinary activities, medical treatment may be able to alleviate the symptoms. Gradual changes in stable angina occur in both directions: chest pain may develop during less-strenuous activities than in the past or may only be provoked by more-strenuous exercise than previously. Occasionally angina may disappear altogether.

An apparent worsening of symptoms is best explained by slow progression of atherosclerotic disease, and seeming improvement by development of effective coronary collaterals. Only when acceleration of angina occurs abruptly should the diagnosis of unstable angina be made.

Prognosis of stable angina pectoris is in principle favorable. Statistical studies of large numbers of patients have shown that those with stable angina who have not sustained ischemic damage to the heart muscle (caused by myocardial infarction or a lesser coronary syndrome) have a life expectancy only slightly lower than that of other their age in the general population. In some patients the benign course is interrupted by one of the more dangerous acute syndromes, but they are obviously in the minority. For purposes of prognosis it is customary to subdivide patients with stable angina into those whose coronary angiogram shows significant disease in only one coronary artery, those with "two-vessel disease," and those with "three-vessel disease." However, statistical differences in life expectancy among these three groups is rather small so long as the left ventricle remains healthy.

Evaluating stable angina pectoris requires a general survey of the cardiac status. The possibility that noncoronary ischemia (such as results from aortic stenosis or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) may be responsible for the symptoms has to be considered. The performance of the heart must be reviewed to determine whether it has suffered myocardial damage. After the presence of ischemia has been confirmed by a treadmill stress test or other diagnostic procedures, many physicians arrange for coronary angiography, though others omit invasive tests if the patient promptly and satisfactorily responds to medical treatment.

Treatment of stable angina involves one of two approaches—medical therapy or interventional therapy (including coronary angioplasty and coronary bypass surgery). Medical therapy of stable angina pectoris is based primarily on the ability of nitroglycerin to provide rapid relief from chest pain. This drug is effective in the form of small tablets that dissolve when placed by the patient under the tongue, once the sole method to control anginal attacks. The 1970s and 1980s saw the introduction of some other effective drugs for preventing attacks of angina. Their use has revolutionized medical therapy of angina pectoris. They are beta-adrenergic blocking

agents, calcium channel blocking agents, and long-acting nitrates having nitroglycerinlike effect. In addition, nitroglycerin can now be administered in slow-release form, as tablets or ointment in patches placed on the skin.

Interventional therapy is effective in controlling angina and is used widely. There is no consensus, however, regarding its indications. The most widely accepted, conservative criteria for intervention include the following:

stenosis of the left main coronary artery

failure to respond to medical therapy

the presence of coronary lesions shown by angiography to be precarious (such as proximal stenosis of the left anterior coronary branch)

evidence that ischemia involves large sections of cardiac muscle

Coronary angioplasty was developed in 1978 and has been a popular alternative to bypass surgery (see fig. 19, p. 55). The technique of coronary angioplasty is described in chapter 4. Originally conceived as a method of dilating proximal stenosis of one of the three major coronary branches in single-vessel disease, the use of this procedure has now been extended to handling lesions in smaller coronary branches and in two- or three-vessel disease.

Angioplasty has proven immensely successful in eliminating or reducing stenosis of coronary arteries by compressing atherosclerotic plaques. However, in about 5 percent of cases the procedure can damage the arterial wall and close off the affected artery altogether. In such cases an immediate bypass operation may have to be performed: standby surgical facilities should be available in hospitals routinely performing angioplasty. Another possible complication of angioplasty is recurrence of stenosis within weeks after the procedure, which develops in 20–30 percent of cases. Repeat angioplasty is usually performed, and the probability of recurrent restenosis is greatly reduced. The advantages of angioplasty over bypass surgery are obvious: it is the simpler of the two procedures, its cost is lower, and recovery is swift.

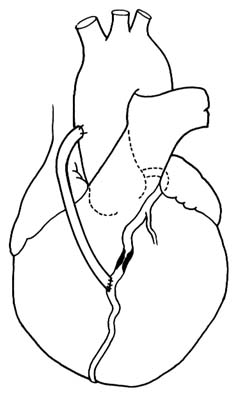

Coronary bypass surgery provides an artificial channel connecting the aorta with the coronary artery beyond the area of stenosis or occlusion (see figs. 29 and 30). The operation is performed under

Figure 29. Coronary bypass graft. A portion of a saphenous vein

from the patient's leg is used to connect the ascending

aorta with a coronary branch beyond the point of severe stenosis.

direct vision as open-heart surgery: a segment of a saphenous vein (a superficial vein running under the skin of the inner surface of a leg) is excised and then grafted to serve as a connecting tube between the aorta and the coronary artery. An alternate method is to connect the lower end of the mammary artery (an artery running inside the chest on either side of the breastbone) with the obstructed coronary artery.

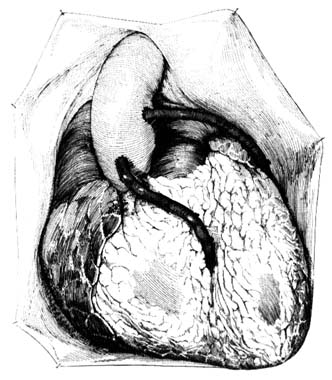

Coronary-bypass surgery is now the most frequently performed cardiovascular operation. More than three-hundred thousand of these procedures are performed in the United States annually. The risk of the operation is relatively small, with mortality rates of 1–5 percent in hospitals with experienced cardiac surgical terms. Patients

Figure 30. Coronary bypass graft as seen with the chest open.

generally tolerate the operation well, and results are usually satisfactory, although closure of the bypass graft occurs in a significant number of cases, particularly if the graft is connected to a smaller coronary branch.

Interventional treatment of stable angina as well as coronary-artery disease does not represent a cure. Apart from unsuccessful results of the intervention (restenosis after angioplasty, graft closure after an operation) progression of the disease in other coronary branches may bring about new symptoms or more-serious manifestations of coronary-artery disease. Repeat operations or angioplasties are often needed even if the original procedure is fully successful. Yet interventional treatment may delay the progression of the disease by years or even decades. Furthermore, enhanced quality of life and freedom from symptoms as a result of interventional

therapy have made it an exciting advance in the management of heart disease. However, statistical proof that patients who have undergone interventional treatment live longer than those treated medically is not yet available, except in some special high-risk situations. This lack of proof is in part related to the fact that the prognosis of patients with stable angina pectoris who have never suffered a myocardial infarction and have normal function in the left ventricle is good.