2—

PROLIFERATING RESPONSES

4—

Contrary to What Is Said:

The Response au Bestiaire d'amour and the Case for a Woman's Response

What kind of beast would turn its life into words?

Adrienne Rich

I should not seem to, be teaching Minerva herself.

Héloïse

As the medieval clergy conceived of it, the "response" (responsio ) was pivotal to the workings of intellectual mastery.[1] In the structure of disputation, it provided a way for the disciple to assume an authoritative role and argue the master's knowledge in his stead.[2] It was the occasion for establishing his position. This process reveals a paradox inherent to the response, and examining its paradoxical character brings us straight to the problem posed by a woman's response. On the one hand, the numerous works designated responses appear repetitive, reiterating the terms established by the master's work. Precisely because the response follows that lead, it is caught in the circuit of the always already said. While it may elaborate upon the masterly prototype, the response serves to reproduce that type, with the result that the respondent is a mimic, cast in the role of yes-man. On the other hand, the response represents a virtual space for difference. Rather than conforming to the contours of the master's earlier work, the response can diverge from its dictates. Point for point, the response can answer in opposition and thereby create a type of counterbalancing resistance. Far from confirming a redundant structure, the response jeopardizes it. Dissembling and combative, in this sense it breaks ranks.

True to its disputational spirit, clerical writing during the high Middle Ages cultivated the paradoxical response form because it could vent various agonistic impulses and in the end resolve them. This is particularly evident in the didactic narratives called enseignements that we studied in chapter 1.

As we saw, the master/disciple rapport was highly charged: both figures were drawn together and polarized by a drive for intellectual control that worked itself out within the framework of their disputation. In fact, it was the very process of working this drive through—of responding in contestatory and iterative fashion—that prepared certain disciples to become master. Far from countermanding each other, the affirming and the oppositional aspects of the response served to secure the same end: the master's dominance and the disciple's eventual graduation to that position.

The thirteenth-century Dialogues de Salemon et Marcoul offers a case in point. In the exchanges between an exemplary wise man and his protégé, Marcoul represents an implicit challenge to Salemon's wisdom.[3] Yet the fact that the lesser Marcoul comes each time to reformulate that wisdom insures the continuity of Salemon's authority:

Dame otroie a ami

Cors et cuers autresi,

Ce dit Salemons;

Fax amanz sanz merci

On meint beax cors trahi,

Marcol li respont.

(stanza 12)

When a lady pledges herself to her lover, she pledges him heart and body; so says Salemon. False lovers are without mercy and have betrayed many beautiful bodies, Marcoul responds to him.

In this kernel of debate between master and student over women, Marcoul's response makes him complicitous with the system of mastery. While it qualifies the master's definition of women, the response still commits Marcoul to the system. So it is with many contemporaneous sapiential narratives; their staging of debates between magister figures such as Aristotle and the inscribed audience of initiates revolves around the dual quality of the initiate's response.[4] By responding to the master's pronouncements, the inscribed audience also undergoes the rite of passage of disputation. Their paradoxical response seals the legitimacy of both the knowledge they are disputing and the system in which it functions. The mechanism of responses works not only to reinforce the complementary positions of dominance and subordination, as Hans-Robert Jauss has argued, but also to authenticate the master's authoritative knowledge by means of the respondent.[5] Rising to respond thus involves participating in the ongoing consolidation of the hierarchical order of mastery.[6]

This reinforcing function is so powerful that it even informs narratives structured only implicitly as responses. Take the example of the Livre

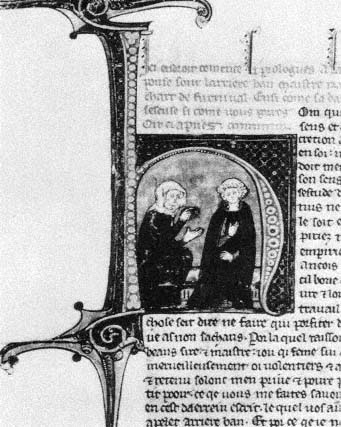

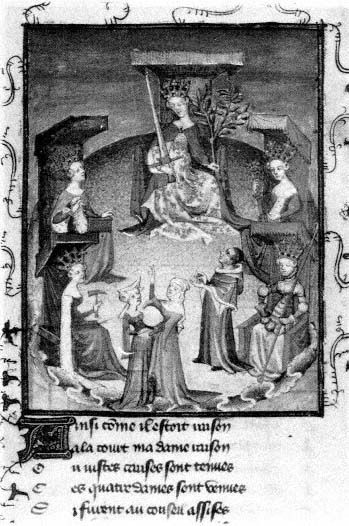

7. Responding in writing. La Response au Bestiaire d'amour .

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Cod. 2609, fol. 32.

Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

d'Enanchet or the contemporaneous Chastoiement d'un père à son fils . They present their sententious material within the framework of a father/son or elder/disciple debate. Through the animated give-and-take of both parties, the father/elder's teachings are finally imparted. The disciple's responsiveness is similarly pivotal insofar as it supplies some obstacle internal to the system of mastery while upholding its logic. Combining a deep-seated sense of respect with a measure of insubordination, these implicit responses constitute the site where the master figure confirms the operations and apparatus of clerical learning.

By delineating the paradoxical aspects of the clerical response form, we can begin to see the problem posed by a woman's response (Figure 7). If the facets of contentiousness and iteration that define a response apply

easily to texts attributed to women, their net result does not. While we have little trouble cataloguing myriad representations in vernacular narrative of women replying oppositionally or iteratively to their male interlocutors, rarely does such narrative yield the profile of a woman master. While the two sides of the response are the veritable prerequisites for the male student entering the system of mastery, in the case of the woman respondent they suggest the limits of her access. They seem to furnish the reasons for her exclusion and progressive objectification by that same system. According to the Ovidian and Aristotelian orders of mastery, the paradoxical response generates, in the case of women, a non sequitur: a female disciple cannot enter the ranks of magistri .

This inquiry into responses attributed to women enables us to break through to the other side of this clerical model of representation. To begin with, doing so involves recognizing the pervasiveness of the tenacious clerical topoi about women during the Middle Ages. It also means reckoning with the tenacious influence they exert over critical discourse today. Across the range of didactic literature, it was the figure of women saying "Yes" and "No," of women responding both iteratively and antagonistically, that pointed to their disqualification from any type of intellectual mastery. The conventional scholastic analysis of feminine responsiveness justified taking women in hand. Indeed the recommendation became an integral element of vernacular clerical learning. In the case of the Bestiaire d'amour , the choice of merging the master and lover personae intensifies the clerical desire to formulate a woman's response as a tacit invitation to ravishment. The Bestiaire narrator's mastery is bound up with the assumption that she would be his yes-woman or that, prevaricating as ever, her contestatory response would signal her eventual capitulation—a far cry from her ever joining his ranks.

Both these designs for the woman's response dramatize the most widely held patriarchal presumptions about female speech. In the case of the iterative response, as we have seen, the issue of redundancy is particularly exaggerated with women interlocutors. Because the medieval clergy interpreted the figure of Eve in such a way as to assert the "natural" repetitiveness of female speech, the woman's response was logically deemed excessive and derivative. Even when this redundancy is cast pejoratively, and Eve is represented as overeager in her responsiveness to the devil, her aptitude for being a yes-woman is underscored. "Original sin" is a consequence of the first woman being too quick to answer. With the oppositional response as well, we find corroborating evidence of a longstanding clerical attempt to conceptualize negativity as feminine. The Ovidian pattern of representing women interlocutors as obstreperous enables the narrators to exacerbate antagonism usefully so as to validate the operations of mastery.

From a clerical perspective, characterizing a response as adversarial and as the work of women amounts to much the same thing; they offer similar ploys in securing the master's authority. This is a ploy that can be used by critics today. When Alexandre Leupin describes the Bestiaire respondent as "a lady who functions as the text's point of refraction, abstention, opposition," he restates a postulate perfectly consonant with those of medieval masterly personae.[7] The woman's response is understood to be negative insofar as it provides the tension necessary to the functioning of mastery. This it does without ever seriously menacing such mastery and without ever including women. In critiquing clerical compositions of the feminine, the danger lies, then, in duplicating or assimilating them to a significant degree.

That the woman's response exemplifies the paradoxical character of the clerical genre, that it accommodates the putative conundrum of women's language: all these signs should alert us to the task of rethinking this category. Further, given the tendency of modern critics to recapitulate the medieval terms of the woman's response in their own work, it is all the more pressing to envisage different models. Are there different ways to contemplate the response inflected as feminine? How do we approach the woman's response in a way that acknowledges the determining influence of its clerical frame without discounting other valences? Such questions call for another critical point of departure. At the very least, they suggest the possibility that the woman's response can be conceptualized differently by modern-day critics. To do so opens up debate over the monolithic character of medieval clerical culture in the vernacular and its central claim of reproducing intellectual mastery unerringly. And these questions chart territory cut by fault lines in the monopoly of magisterial learning—fault lines that betray the disturbances caused by women's involvement uncovered in chapter 1.

The category of the woman's response thus becomes a key site for interrogating the structures of intellectual mastery and critiquing its symbolic domination. This critique builds on the disciple's discourse, which already brings to the surface some of the inherent weaknesses of mastery. The inscribed woman respondent occupies a disputational position similar to the disciple's. But because its critique focuses on the effects of mastery, the woman's response goes beyond the disciple's to contest the problem of the symbolic domination of masterly writing. This contesting, let me emphasize, does not involve women alone. I use the term "woman's response" to describe an attribution. The woman's response can refer to clerical forms within the world of mastery that are merely voiced by women. But the fact that such attributions were made helped create the occasion for actual women to rise to the challenge of responding. With the

advances in lay literacy during the later Middle Ages, the clerical version of a woman's response inside the masterly domain invited women outside to forge their own.

I wish to broaden the issue of the woman's response considerably—beyond that of the speech act. The response also represents a genre of text in action. As such, it is linked progressively with a variety of textual registers, with philosophical as well as amorous discourse. Such an inquiry leads to pondering the implications of individual response texts, for they signal reactions to the predominant textual practices of the clerisy. By working outward through concentric interpretative circles, my exploration of the woman's response will then move in turn from discursive strategies to specific episodes of public debate over clerical textual practices. As I suggested in the introduction, the largest, most ambitious interpretative circle will thus examine the woman's response as a social movement that calls to account clerical conceptions and figurations of women.

Because the notion of woman's response is relatively unfamiliar, I shall begin with the simplest concerns: how to respond? why respond? who is responding? The Response au Bestiaire d'amour serves as a test case for exploring these questions.[8] Not only does this late-thirteenth-century narrative constitute one of the earliest replies to a master's text already in circulation, but it responds with remarkable erudition to the style and substance of that text. Engaging with the master, the Response begins by commenting on the creation of women. It takes up the master's eroticized exegesis of bestiary exempla point for point so as to question his interpretations and their underlying intentions. This questioning results in a meditation on the public force of language. For these reasons, the Response au Bestiaire will also serve as a fulcrum text: as I hope will become clear over the next four chapters, it structures my thought on the phenomenon of the woman's response per se.

How to Respond?

The woman answering the Bestiaire master grounds her response in what I shall call a principle of contrariety:

Tout autel vous puis je dire que puis que je seroie contraire a vostre volenté et vous a le moie, et que nous nous descorderiens d'abit et de volenté, je ne me porroie acorder a vostre volenté comment que vous vous acordissiés a moi.

(Segre, 113)[9]

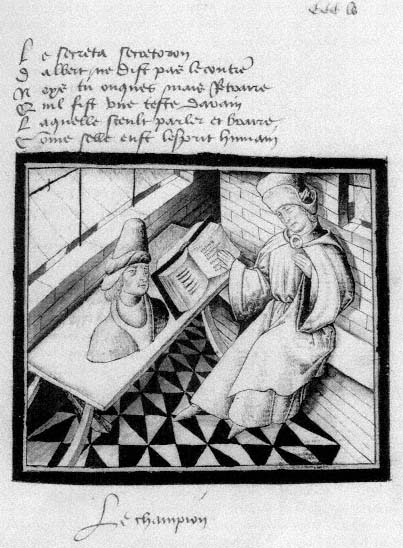

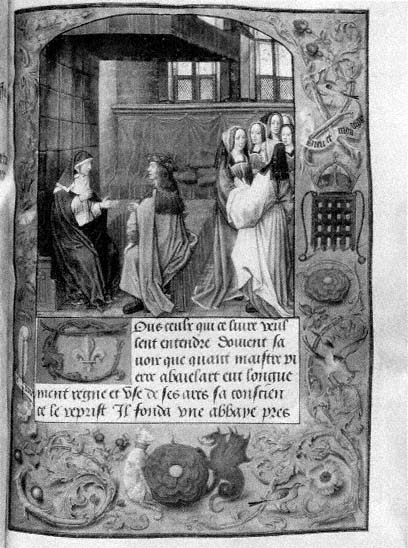

8. In the heat of debate. La Response au Bestiaire

d'amour .

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek,

Cod. 2609, fol. 34.

Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

Likewise, I could tell you that since I would be contrary to your will and you to mine, and we would disagree both in habit and in will, I could not agree with your will however much you might agree with me.

This is no mere disagreement (Figure 8). From the outset, the respondent introduces a logical structure that establishes a principle of contrariety and sets it in relation to contradiction. Whereas contradictory objects are mutually exclusive, thus canceling each other out logically, contraries constitute coexisting differences. That is, they are defined oppositionally to each other in a way that admits the separate distinctiveness of each other. Contrary pairs can stand side by side despite their evident opposite properties.

This logical distinction between contrariety and contradiction is often muddled today. The result is that they are conflated, understood to signify a single, amorphous type of negation. But in their original Aristotelian formulation in the square of oppositions, the distinction was rigorously maintained.[10] If we recall the preponderant Aristotelian substratum for

most high-medieval masterly works, especially for Richard de Fournival's Bestiaire , the woman respondent's choice of this logic is noteworthy. On one level, this contrary logic places her writing on a par with her interlocutor's: she is represented as his intellectual match. On another, her use of the terms of contrariety sets her at complete odds with several of the Master Philosopher's most formidable theories. It transforms the notion of contrariety to women's advantage.[11] In effect, the Bestiaire respondent works a contrario so as to argue against the Aristotelian postulate of the incomplete woman and its corollary of her irrationality. That the respondent retrieves one element of Aristotle's thought in order to contest another means turning the entire corpus of Aristotelian learning against itself. This iconoclastic brand of argumentation undergirds her contrary choice of how to respond.

Questions of knowledge offer the first arena in which the issue of contrariety is tested in the Response . In the prologue, the respondent acknowledges that any transaction in knowledge operates differently according to gender. Furthermore, given the relations established by the Bestiaire , a woman recipient of the master's teaching risks being adversely affected. But here this sort of scholastic discrimination prompts her to espouse a knowledge specific to women:

Et pour che, biaus maistres, vous proi je que selonc che que vous m'avés dit ne tenés mie a vilenie se je m'aïe de vostre sens, selonc che que je en ai retenu. Car encore ne puisse je savoir tout che que vous savés, si sai je aucune chose que vous ne savés mie. Dont il m'est bien mestiers que je m'en aïe selonc che que li besoins en est grans a moi, qui feme sui.

(Segre, 106)

Dear master, I ask you in accordance with what you have told me, not to take it badly if I avail myself of your meaning insofar as I have understood it. For although I cannot know all that you know, I do know something which you do not know at all. So it behooves me to take advantage of it, since I, as a woman, have great need of it.

This respondent maps out her own intellectual province. The Bestiaire master's erudition notwithstanding, she reserves for herself something inaccessible to him. Her distinct and separate knowledge is fundamentally allied with the subjective enunciation: "je . . . qui feme sui." Not only does she recognize gender's part in the production of knowledge, but she asserts her intellectual power on that basis. The claim to her epistemological field is made on the strength of her subjective identity: one gesture follows from the other. Together they suggest this respondent's very different approach to learning. Instead of meeting the master's erudition

head-on, in the habitual agonistic stance, the woman respondent defers rhetorically. She bows and scrapes in a familiar posture of humility. Yet this self-deprecating manner, which Hélène Cixous has dubbed wittily the rhetoric of sexecuser , is the very means whereby she can move past the stark, mutually reinforcing confrontations between antagonists.[12] A semblance of acquiescence can point the way out of a magisterial system of controlling conflict. By configuring difference in nonexclusive, nonadversarial terms, the Bestiaire response posits a woman's knowledge that is not defined in contradiction to the master's. It advances an oppositional epistemology. From the very beginning, this respondent argues for a specifically feminized relation of contrariety with the world of clerical learning.

In this context, she sets into play an alternate account of female generation. Having distinguished the particular terms of her knowledge, the respondent proposes a different model of creation. Her version recoups the theory of dual creation from Genesis 2, a theory discounted by orthodox Christianity and yet widely circulating in apocryphal form in Talmudic exegesis and elsewhere.[13] In other words, the female persona deploys a reading at complete odds with the canonical account of Adam's rib. Its deviance is twofold; for not only does it describe the woman's birth as simultaneous and independent of the man's, but it relates how he murders her:

Dont il avint que quant dex eut doune lun et lautre vie et cascun forme et doune a cascun sens naturel, il lor conmanda sa volente a faire. Et ne demora mie longues apries quant adans ochist sa feme pot aucun courouc dont ie ne doi ci faire mention. Dont saparut nostre sires a adan et li demanda pour coi il avoit ce fait. Il respondi ele ne m'estoit rien, et pour cou ne la poole iou amer.

(Vienna 2609, fol. 32 verso; Segre, 107)

Then it happened that when God had given to one and the other life, form, and natural intelligence, He commanded them to do his will. And it was not long after that Adam killed his woman out of anger, which I shall not discuss here. Our Lord then appeared to Adam and asked him why he had done this, and Adam replied, "She meant nothing to me and so I could not love her."

Through such a scene of murderous violence, the woman's response develops its contrariety in two further ways. First of all, it confronts the preeminent topos of a nefarious woman apt to kill the lover. If the Bestiaire lover complains of the siren's lure, here, the respondent points out, the first woman is killed without provocation. Her answer to the master's symbolic death is to match it and deflect it with her own. Moreover, her

rendition of Adam's crime offers a parable of man's enormous difficulty in entertaining any contrary element, for he is represented killing out of sheer ambivalence toward Eve's existence: "ele ne m'estoit rien." His reflexive reaction is to strike out her being; even in Eden, man's antipathy toward a potential female rival generates violence against her.

Despite its violent and misogynistic terms, the lesson of this parable is far from grim. By reviving an alternative account of woman's genesis, the respondent comes to argue for a superior female composition. This is an argument concerning matter well known by the late thirteenth century: "Adam was made from the mud of the earth while Eve was made from Adam's rib" (de materia qui Adam factus de limo terre, Eva de costa Ade).[14] The respondent bolsters this argument with the language of Aristotelian materialism and contends that the first woman's murder occasions a new female creation of more suitable material, "de mains soufissant matere."[15] Made from peerless ingredients and still further refined, the species of woman is a handiwork apart. Since God continues to work over the matter of the first man, he produces in the woman a better artifact—"une matiere amendee" (fol. 34). The second, female object builds on the original, enhancing it. No mere pejorative sign of derivation, the respondent's Eve exemplifies a perfectible human being. Such an account is confounding insofar as Eve's origin in the male body does not prove her inferiority, as Aristotelian wisdom and countless medieval commentaries would have it. On the contrary, it proves her greater integrity.[16] While the respondent retains the shell of this well-known scholastic argument, she changes its very matter to discomfiting effect.

I play with this pun on "matter" here because it is in perfect keeping with the respondent's tactics. Her experiment with the term "matter" salvages it from its usual disenfranchising Aristotelian context and casts it anew. This she accomplishes by parodying the concept of sufficient matter (souffisant matieres ), usually reserved for the concept "man" to the detriment of "insufficient woman." By forging the notion of "improved matter," the respondent can place a woman in a category apart. Her recuperation of Aristotelian formulae turns the criterion of matter to women's advantage, for it refers to both the raw materials of creation and those of writing. The two "matters" are often combined so that the respondent's text reads like a multilevel commentary on this primordial issue. Again and again she returns to it, developing the links between the creation of the first woman and the fashioning of her text. What matter makes up her writing? In the wake of her anti-Aristotelian meditation on matter, the respondent envisages a female matter relatively free of disabling connotations.[17]

This notion of matter as writing material sets up her exploration of the master's characteristic figurative language. In exegetical style, she approaches tropes as the building blocks of clerical composition. And the figure singled out epitomizes the clerical project to render women figuratively. In the respondent's terms, it is "the castle that is woman." This figure of the female body as military fortification is so endemic that most medieval works assess it from the outside alone—as a facade to scale, a construction to besiege and overwhelm. The only perspective is that of the aggressor. Remarkably, this woman's response places us within the castle wall:

Et por cou qe chastiaus de feme si est souent pourement porueus solonc cou que dex sine douna mie si ferme pooir a la feme come il fist al home: mest il roestiers de meillor garde auoir qe il ne feroit uous qi hom estes solonc cou que deuant est traitie. Et uoel uenir a cou que corn il soit ensi que dex uous ait done plus ferme pooir: ne fu il pas si uileins que il ne nos donast noble entendement de nous garder tant come nous nos uorrons metre a deffense. Et por cou que iou ai oi dire que il nest plus de faintisses que de soi recroire rant come force puist durer. Iou ai mestier que ie gietie de mes engiens au deuant et face drecier perieres et mangouniaus ars atour et arbalestres a cest chastel deffendre que iou uoi que uous auez asailli.

(Segre, 105)

The castle that is woman is so poorly protected because God gave much less firm power to woman than he did to man. It is necessary for me to be on close guard against you who are a man as was mentioned before. And so I wish to come to this point: since God gave to you this greater power, it would have been wicked if God had not given us noble intelligence so that we can protect and defend ourselves properly. And so I have heard it said that it is hardly cowardly to renounce the fight so long as force prevails. It is crucial that I employ my shrewdness, that I know how to deploy my weaponry in order to defend this castle, which I see you have already assailed.

The response makes over the castle so that the audience can observe the trope working from a contrary position—from inside the female body. There is no impetus to dismantle the predominant figurative structure. Rather, the move is to open it up and examine it ironically from the inside out. The castle still stands, but in disarming fashion it is represented subjectively, as feminine. From this rarely adopted vantage point the respondent converts the standard elements of the erotic trope according to an explicitly defensive vision.

Central to this problem of defense in the Bestiaire Response is a conception of power that contrasts the physical force of man with the

intelligence of woman. Such a conception redresses the usual balance of power whereby the cognitive belongs exclusively to a man on the attack. Here, by contrast, the woman is credited with rational faculties and her putative physical vulnerability acts as a cover for them. As Elizabeth Janeway has elucidated, the patriarchal presumption of feminine weakness can translate for women into a show of improbable strength.[18] By protesting her limitations, the respondent, in fact, musters her own intellectual resources. What's more, she exercises them in her defense. The flourish of naming weaponry, "perieres et mangouniaus ars atour et arbalestres," identifies a woman's resources in the very figurative idiom that is, as a rule, marked off-limits to her. Unlike the women in Capellanus's De amore , this respondent is adept at allegorical discourse and uses it to construct her rhetorical defense. Not only does the Response disclose the destructive motives behind a hallmark clerical symbol such as the castle, but it represents a woman wielding the master's figurative language to her own ends.

Such a strategy is conceived in terms of the recurring issue of matter:

Premierement iou uoel qe uous sacies de qoi iou me uoel deffendre contre le premier assaut de cest arriere ban que uous auez amene sor mi. Iou qui principaus sui de la guerre ameintenir vous fac sauoir qe se uous fussies auises dune chose dont iou me sent forte et garnie que molt le doit on tenir a merueilleuse folie. Et ne tenes mie a mencoigne la raisson tele come ie le uous dirai solonc cou qe iou lai oie. Il est uoirs qe souent auient que li fors sil ceurt sus le foible por ce que il ne salt pooir de deffendre. Et por cou que uos cuidies que ie meusse pooir de deffendre mauez uos del premier enuaie. Or uous semble qe uous ne seres ia recreus, tant come alaine uous dure. Et iou mestres si me deffenc de ce que iou daussi soffissant matere sui engenree et fake come uous iestes qui seure me coures et le uous uoel prouuer ensi.

(Segre, 105–6)

First of all, I want you to know, I can defend myself against the first assault that your writing has directed toward me. I, who am the principal defender in the war, must advise you that I feel strong and well guarded, so much so that some might take it as wild folly. Don't take lightly the reasons that I am telling you according to what I have heard. True, there are those who secure their strength on the weak since they do not know how to defend themselves; so you may think that I do not have the power to defend myself and that you have me at the first shot. It may seem to you that you will never be vanquished so long as you have breath. But I, master, defend myself because I was engendered from just such sufficient matter as you who are secure, and I want to prove it to you in this manner.

The feminized trope of the castle constitutes an inviolable defense because of its makeup. Since the first woman is distinguished from Adam on the basis of her material, so too are the respondent's figures. The bedrock of a contrary female substance transforms the significance of her symbolic structures. Engendered from a different, yet equally suitable matter, she is depicted as one who takes the initiative in conceptualizing her body anew and defending it rhetorically. Thereby she is shown to gain a masterful position. This last point may appear dubious. The epithet, maistres , slips in subtly, like so many gestures of respect. We are accustomed to read it in terms of the clerkly interlocutor. But the phrasing is unlike any other in the text. It can qualify her subjective stance. This possibility of it referring to the female subject—iou mestres —inflects it otherwise. For the woman respondent to articulate her subjective power in a reformed symbolic language implies a mode of mastery.

The chance of her assuming this title calls into question the relations governing the Bestiaire and its Response . The figure of a female master reverses the conventional dynamic between an irreproachable magister and his pusillanimous female pupil. This reversal is all the more apparent in a woman's response that puts on the mantle of scholastic authority with such ease. Her text reads as a scholastic set piece comparable to the Bestiaire and far surpassing most contemporaneous Old French texts. Small wonder then that the Response pushes still further the connection between female matter and symbolic language.

The respondent's next argumentative move is paradoxical, for it reaffirms the orthodox hierarchy "in which the woman should obey the man, and man the earth, and the earth the Lord Creator who rules over all creatures" (dont doit la feme obeir al home et li hom a la terre et la terre a diu ki creeres fu et souverains de toute creature; fol. 34). The respondent can afford to reiterate the quintessential scholastic view of world order because a woman's domain has already been staked out. At the heart of this divinely ordained system there is a designated material site at complete odds with it. Yet situating womankind in this different matrix does not necessitate destroying the superstructure. Beyond any mere iconoclasm, the respondent's debate with the master bespeaks the desire to design a rhetorical and epistemological space for women. This is a space both contiguous with and outside the bounds of man's dominion. While located within the conventional superstructure, it is also disengaged from it. At the very moment of taking on the master, the narrative lays out this contrary space as a legitimizing ground for a woman's response.

I have teased out the prologue of the Response au Bestiaire line by line because it clearly articulates the axiom of woman's contrariety. Beginning

with beginnings, this narrative posits a distinctive female matter, and with it a different epistemology. On these twin bases, the respondent can answer the master efficaciously. For she is positioned right away in a contrary relation to the master's erudition and can thus dispute his propositions. Having forged a way to respond, the narrative moves on to confront the problem of a dominant figurative language. It tackles the question: why? If the prologue lays the groundwork for a woman's response, then the main narrative shows why it is crucial for her to answer the master. The Response builds on the incipit alluding to the potential damage of linguistic constructions: "Nothing should be said or done to hurt a person" (a cose nule dire ne faire par coi nus ne nule soit empiries; Segre, 105). The focus is on gauging the effects of clerical composition.

Why Respond?

Faced with the master's bestiary figures, the respondent makes the following observation:

Car je sai vraiement qu'il n'est beste qui tant fache a douter comme douche parole qui vient en dechevant. . . . Car vos paroles ont mains et piés, et sanle vraiement que nule raison ne doi avoir de vous escondire cose que vous voeilliés.

(Segre, 118)

For truly I know that there is no beast who should be feared like a gentle word that comes deceiving. . . . For your words have hands and feet, and it truly seems that I can have no reason to refuse you anything that you want.

In her hands, the habitual figurative equation breaks down. The bestiary metaphor no longer refers to an aspect of human erotics but to language, specifically the master's "gentle deceptive word."[19] The respondent's analysis goes on to demonstrate the treacherous character of his bestiary formula. It is not the woman who is dangerous like a siren or vulture, but rather the master's discourse, which transforms her symbolically into such a creature. The "beasts" to watch out for are those figures describing women in consistently noxious terms.

The respondent's metaphorical equation is doubly ironic. Rending the veil of the master's metaphors, it unmasks the manipulative design behind the prevailing symbolic language. Since her metaphor identifies the master's "soft word" as an instrument of deception, it implies that all those sinister, threatening, female personae in the master's Bestiaire are a form of

9. Further disputation. La Response au Bestiaire

d'amour .

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek,

Cod. 2609, fol. 44.

Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

displaced animus, an expression of the misogyny informing medieval vernacular writing. This ironic finding is itself cast metaphorically. The respondent does not relinquish the privilege of figuration even in the act of criticizing its conventional uses. As in the prologue, her dispute with the master's language is played out on the same level (Figure 9). It works through a recuperated and transformed figurative idiom. But of what kind? Presented as a subjective truth claim (car je sai vraiement), the respondent can appraise magisterial symbolic language differently, in a language particular to a woman. Anchored in this "I" (je . . . qui feme sui ), her critique deploys a figurative register that is by definition contrary to the master's.

We come here to a crux in the Bestiaire Response . If this narrative breaks down the magisterial symbolic language, why does the female persona persist in analyzing the various bestiary exempla? Part of an answer involves the principle of gender contrariety undergirding this narrative. With each new bestiary metaphor, the Response pushes the difference further between a woman's analysis of the symbolic and the master's. Her explications de texte operate according to a different logic that necessitates a distinct language. Precisely because the respondent is represented

contesting the master's entire repertory of bestiary images, the principle of feminine contrariety is systematically developed—linguistically, as well as epistemologically and materially.

The reason for developing it systematically (and here we get to the other part of the answer) is the respondent's thesis that the master's discourse is deceitful. If the Response is to demonstrate "what she knows to be true" (line 1), that is, the profound deceitfulness of such language toward its intended female audience, then it must do so on a comprehensive scale. For anything less would serve only to reinforce the master's discourse. In order to prove how it works to the detriment of its female public, the Response mounts an exemplum-by-exemplum critique.

Consider, à titre d'exemple , the Response's undoing of the wolf exemplum:

Je doi bien dire que je fui premierement veüe de vous, que je doi par cesti raison apeler leu. Car je puis mauvaisement dire cose qui puist contrester a vous. Et pour che puis je bien dire que je de vous ai esté veüe premiers: dont je me doi bien warder, se je sui sage.

(Segre, 110–11)

I must well say that I was seen first by you, who I must for this reason call the wolf. For I can only poorly say anything that could counter you. And for this reason I can well say that I was first seen by you, and I must be on guard if I am prudent/wise [sage ].

We remember the master's ploy of feminizing the wolf and taking it upon himself; here the respondent is quick to thwart the maneuver. She catches the master acting the helpless woman. Her analysis reveals the transfer mechanism of his feminine figures and their potentially detrimental effect. In turn, the respondent reverses the transfer. She makes the wolf signify again a predatory animal, and by inference, the master. This reversal is couched in the self-deprecating terms typical of the prologue: the sexecuser rhetoric prevails. But as we have seen, this rhetoric can belie an improbable flourish of knowledge, in this instance a pun on sagesse . Referring to both prudence and wisdom, this play of words highlights the fundamental connection between wisdom and self-protection. Whereas the master's sagesse suggests an outward, aggressive motion, the woman respondent's, by contrast, entails an inner consolidation. In this sense, her interpretation of the master's predatory figure does not launch a comparably predatory language.

Using the master's tropes for seduction, the Response extends its exposé of their harmful effects. Take her reading of the tiger:

Car je voi bien et sai que tout aussi que on giete les miroirs devant le tigre pour lui aherdre, tout aussi faites vous pour mi vos beles paroles qui plus delitaules sont a oïr que tigres a veoir, si comme deseure est dit. Et bien sai queil ne vous caurroit qui i perdrist, mais que vo volentés lust faite.

(Segre, 117)

For I clearly see and know that just as one casts mirrors in front of the tiger to catch it, so you make for me your beautiful words. They are more delectable to hear than the tiger is to see, as has been said above, and I know well that it would not concern you who perished by them as long as your will be done.

The Response returns to the traditional bestiary typing of the female tiger—a revision that, at first glance, appears to reinforce the clerical commonplace of the narcissistic woman. Yet if we look closer, the comparison between the beauty of the tiger and the more beautiful words of the master shifts attention away from the putative issue of female narcissism and toward the damaging function of the mirror. The problem is less one of a woman enthralled by her self-image than of the mesmerizing quality of the master's words. The respondent's contrary metaphorical formula equates the master's comely discourse with the fatal attractions of the mirror. It also makes explicit the dialectical terms of power so characteristic of the master's reasoning: "And I know well that it would not concern you who perished as long as your will be done" (Et bien sai que il ne vous caurroit qui i perdrist, mais que vo volentés lust faite). Uncovering the master's show of will (vo volentés) gives the respondent more reasons why she should argue against him.

If the Response exposes the malicious tropes for seduction, it also challenges their various symbolic associations with death. Hence the elimination of all the master's figures for resuscitation and resurrection. In the woman's schema, there is no place for the pelican, lion, and beaver exempla for the simple reason that once seduction is interpreted as a form of death for a woman, it is absolute. As the respondent describes it: "For who loses his honor is truly dead. Indisputably it is true: who-ever is dead is unlikely to recover" (Car qui s'onneur pert, il est bien mors. Certes c'est volts; qui mots est, pau i puet avoir de recouvrier; Segre, 121).

A figure unique to the Response equates such "death" with a threat of sexual violence:

Tout aussi comme li cas qui a ore mout simple chiere, et du poil au defors est il mout soues et mout dous. Mais estraingniés li le keue: il getera ses ongles fors de ses .iiij. piés, et vous desquirra les mains se

vous tost ne le laissiés aler. Par Dieu, je cuit aussi que teus se fait ore mout dous, et dist paroles de coi il vauroit estre creüs et avoir se volenté, que seil en estoit au deseure et on neli faisoit du tout se volenté, qui pis feroit que li cas ne puist faire.

(Segre, 123)

Just like the cat who has the straightest face, and the softest, gentlest fur outside, is very sweet and gentle. But were you to pull its tail, then it will stick out its claws on all four paws and rip your hands to pieces until you let go. By God, I believe there is that type of man who is all gentleness and who speaks words to convince you and to get his way, and yet he is capable of far worse, were he on top and not getting his way.

The cat exemplum dramatizes the nexus in the master's amorous discourse of elegance, malicious intent, and force. The effects are graphically portrayed: what passes for love talk is a language of physical blows. There is little mistaking the image of the cat on top for the type of sexual force described in the Aristotelian didactic treatises considered in chapter 1. The respondent's original trope underscores the link between the master's exquisite figurative language and its domineering impetus expressed in sexual terms.

At these junctures, where the Response supplants the master's figures with its own, the full import of its contrariety comes into focus. Dismantling the Bestiaire 's metaphors, stroke for stroke, exposes the detrimental power of the master's language. It shows the harmful aftereffects of that language on the public of women. In short, the Response formulates the problem of verbal injury. There is no quibbling or self-belittling rhetoric here: it disputes the amorous discourse of the Bestiaire on the grounds of its mjunousness.

The linchpin of this indictment occurs in a mock dialogue between lovers:

Mais che seroit bien parlers a rebours se je disoie a aucun cose dont il me vausist traire en cause et mener maistrie seur moi. Car mout se moustrent bien amours ou eles sont, si queli parlers et li descouvrirs amie a son ami, ne ami a s'amie, n'est fors parlers a rebours. Jou ne di mie que bien n'ait raisson de dire amie a son ami: "Il me plaist bien que toute li honneurs et li biens que vous poés faire soit en mon non"; et chil a l'autre lés dira: "Dame, ou damoisele, je sui du tout sans contrefaire a vostre volenté." Mais dire: "Amie, je me doeil, ou muir, pour vous; se vous ne me secourés je sui traïs et me morrai," ja, par Dieu, puis qu'il se descouverra ensi, je n'i arai point de fianche; anchois me sanle que teus paroles sont mengiers a rebours.

(Segre, 129–30)

But that would be "speaking at cross purposes" if I were to say something that he could use against me and thereby master me. For love truly shows that talk and secrets shared between lovers, whether woman to man or man to woman, is nothing more than "speaking at cross purposes." I am not saying that it is not right for a woman to say to her lover: "It is pleasing to me that all the honor and good that you accomplish is done in my name" or that a man says to her: "Lady, I am completely at your service." But to say: "Lady, I'm tormented, I'm dying for you; if you do not save me, I am betrayed and shall die." My Lord, whosoever reveals himself in that manner is not trustworthy. Such a talk, it seems to me, is "eating [speaking] at cross purposes."

All the key elements of the respondent's analysis converge in the term "parlers a rebours" (speaking at cross purposes). First: the issue of figurative language. The risk of speaking at cross purposes arises from the metaphors specific to amorous discourse. This is especially the case with the paradigmatic figure of lovesickness, li maux d'amour . By resorting to such metaphors, both men and women run this risk. Second: the drive to dominate. At the core of such a figurative parlers a rebours is the desire for domination, flagged by the vocabulary of will (volenté ) and mastery (maistrie ). Once we recognize the connection between figuration and domination, the differences between so-called masculine and feminine rebours are patent, and those differences are bound up with the desired effect on the interlocutor. Whereas the respondent evaluates a man's speech act—the infamous death threat—as manipulative, she introduces no female analogue. In fact, the woman's speech act may result in her being mastered herself (se je disoie a aucun chose dont il me vausist traire en cause et mener maistrie seur moi). This scene is set up hypothetically (che seroit . . . se je disoie). As if for argument's sake, the respondent considers the possibility of a woman speaking a rebours , but it remains pure conjecture. On two scores, then, the Response argues that it is virtually impossible for a woman to speak in this manner. Since her own figurative language reveals no dominating impulse, it does not impose the respondent's will on her audience. And since her male interlocutor is incapable of understanding the recourse to figurative language otherwise, he is likely to exploit hers as an opportunity for his own mastery (et mener maistrie seur moi).

Through this notion of parlers a rebours , the Response brings pressure to bear on that proposition linking figurative language to domination. It calls to account the process whereby the figurative speech act inflicts harm, a process so utterly conventionalized through the configurations of

vernacular writing that it appears unremarkable—except, according to the Response , in the case of women speakers. Precisely because their language shows no signs of injuriousness, because the male interlocutor interprets it instead as an invitation to overpower, that proposition breaks down. What is rebours , then, is not a woman's negativity, as the master's paradigm would have it, but rather the potential destructiveness of the reigning figurative language. Parlers a rebours exemplifies the system of mastery operative in vernacular love narratives insofar as it reveals how its founding theorem—using the figurative ® achieving dominance—is invalid for a woman. She is represented as neither able to achieve a dominant position through the figurative nor desirous of it. For a female persona, such a proposition does not hold.

Having explicated the domineering function of men's parlers a rebours , the Response pins it explicitly on the clerical caste:

[C]he sont chil clerc qui si s'afaitent en courtoisie et en leur beles paroles, qu'il n'est dame ne demoisele qui devant aus puist durer qu'il ne veullent prendre. Et sans faille bien m'i acort, car en eus est route courtoisie, si que j'ai entendu. Et en aprés sont li plus bel, de coi on fait clers, et sont li plus soutil en malisse, et sousprendent les non sachans. Pour che les apele je oisiaus de proie, et bon feroit estre garnie contre aus.

(Segre, 133)

These are clerks so expert in courtesy and fine talk that if they are after women, there is no one, neither lady nor young girl, who can withstand them. And I can well understand, for these men are impeccably courteous, according to what I've heard. And moreover they are among the most handsome which is why they are made clerics, and most subtle in their malice, and they outwit the untrained. For this reason, I call them birds of prey, and it would do well to guard oneself against them.

This is no standard outburst of anticlericalism. Instead of attacking clerks for what they are lacking, as in the long line of clerc/chevalier debates, the Response focuses on their outstanding talents. The clerical skill in formulating intellectual problems, subtilitas , transmutes into a form of malice. It signals a perverse desire to use those skills to the detriment of others. Whence the relevance of the birds of prey exemplum: the nefarious "beles paroles" of the clergy resemble so many snares for the unsuspecting. Rather than use this exemplum to describe the animalistic quality of erotic relations, the respondent works it back the other way, portraying how bestial the clerical representations of those relations are, which she describes elsewhere as "wounding, beautiful talk" (si trenchans cose n'est comme de bel parler; Segre, 118).

Just as the respondent disputes clerical figuration per se, she defends

women in general. Increasingly, she speaks on behalf of "all those women who need persevere in love" (toutes celles qui enamor vauront perseverer; fol. 33). These inclusive gestures function both negatively and positively. Negatively, they function as a caveat, because the respondent depicts those gullible women who "thrill to hear the clerks' words" as an antitype (celes qui s'aerdent a escouter leur paroles; Segre, 134–35). She uses them to designate the female type targeted by clerkly amorous discourse. In fact, the Response goes so far as to show the way deceived women often reproduce their own deception among other women (Segre, 132–33). At the same time, the Response projects a positive female type, an image around which women can rally so as to avoid complicitous self-deception.

Tout aussi vaurroie je vraiement que toutes se vardassent . . . que quant .j. venroit qui si feroit le destravé, et puis si li deïst on une cose que il feroit le plus a envis et dont mains de damages seroit.

(Segre, 130–31)

I would truly like all women to watch out for themselves . . . so that when a man comes along and acts desperately, he would then be told something that he would do most begrudgingly, and from which the least damage would ensue.

In a gesture of solidarity, the respondent envisages those women who could deflect the advances of a feigning male interlocutor. She hypothesizes a general guardedness in women. What is most striking about this projection is the aim of avoiding all destructiveness. In this scenario, the woman's response to the feigning male speaker incurs little or no damage (dont mains de damages seroit). Unlike clerkly amorous discourse, a woman's speech act has no backlash on its intended audience. The destructive character of a man's requeste is not met in kind.

To the question why respond? then, the Bestiaire Response replies not only "Because," as the response form dictates, or "Because a woman should," as the gendered logic of contrariety has it, but most importantly, "Because clerical discourse should answer to a woman's charge of injuriousness." Herein lies the innovation of this text. Rarely did French narrative of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries represent the act of bringing an accusation against a discourse. However self-conscious this culture was about literary composition, it was preoccupied for the most part with the process of writing. Even when it broached the problem of a writing's effect on its audiences, this did not implicate its own practices. At the time of the Bestiaire Response , Old French literary culture seldom pursued the possibility that it could commit acts of verbal injury so abundantly in evidence in other contexts. Like the clerical catalogues detailing

various verbal infractions, narratives in the line of the Roman de la rose addressed the problem only to locate elsewhere. To be sure, this culture was concerned with slander and calumny and all malicious language meant to harm. Such are the habitual complaints about mesdisants (gossips, slanderers).[20] Yet the concern over mesdisance involves a threat coming from outside the domain of amorous discourse. Never is mesdisance associated with or deemed representative of a normative discourse.

Bringing the charge of verbal injury against the prevailing masterly discourse makes the Bestiaire Response singular in another way. It locates all problems of textual representation in the social domain. Its attention to the effects of figuration places that figuration in relation to a community. In turn, the Response suggests that group's chance of regulating it. The case of one respondent does not constitute a community, especially when she is part of the intricate configurations of erotic/didactic narrative. Yet the fact that the Bestiaire respondent evaluates the ways textual representation can injure a public raises in a powerful manner the idea of social controls. The fact that a female persona raises the idea of verbal injury in terms of a female public bespeaks a critical connection in late medieval culture between women and the social accountability of clerical discourse. I shall return to this point again and again.

Naming Names

Surprisingly, in one instance we are able to see how the Response 's charge against clerical discourse resonated for some of its audiences. In one manuscript, the Bestiaire and Response are followed by yet another woman's response (hereafter referred to as Response 2).[21] Someone saw fit to extend the exchange between master and respondent and to pursue the problem of injurious language. At the center of this second Response is the question of fame or reputation.

By taking up the topic of reputation, this text builds on the question of a discourse's effects posed in the first. It considers the object of such discursive damage: women's names. To broach this topic represents another effort to dispute the masterly discourses. In the largest scheme of things, it suggests other ways of naming women.

Response 2 introduces the notion of a name as a symbolic value established publicly. In contrast to proper names such as Marie or Blanchefleur, the name it considers refers to the sum of properties that a person/ persona represents for a particular community.[22] As the woman respondent stresses, it is constituted primarily by those discourses in public circulation:

Et dautre part sens et valours si sunt ausi comme ensamble quant il sunt sans loenge, ne mis ne doit savoir quil soit larges et boins sil na autre tiesmoingnage que lui li quel lensiucent et sacent que cou soit voirs par le conversation quil ait entre eaus.

(Vienna 2609, fol. 46)

And on the other hand, if the intelligence and reputation [of a person] are also together when they are without praise, it is impossible to know, and indeed one should not know, whether they are widespread and good unless there are other witnesses that follow from it and know it to be true from the conversation that there was between them.

Everything hinges on the ways a person is represented before the public. However deserving an individual, his or her good name depends on the witness of others. Reputation is contingent on the prevailing public discourse. It follows, then, that the process of gaining a reputable name is necessarily subject to what the respondent calls "conversation . . . between them" (le conversation quil ait entre eaus; fol. 46). Caught in the web of such discourses, a name cannot escape their terms. On the one hand, there is the model of panegyric (loenge , fol. 46), an excessive, idealizing discourse that Leo Braudy has associated with the "frenzy of renown." And on the other, there are multiple negative forms—damning praise (fausse loenge , fol. 46), "name-calling," outright denunciation. Common to both these discursive modes is the threat of falsehood. In the public domain where the recourse to witnesses and the criterion of verifiability do not hold uniformly, the status of names becomes increasingly difficult to evaluate. How to account for the discursive involvement of others in shaping a name? If a person/persona can exist publicly in name only, how exactly is that name created and regulated?[23]

The Response reformulates these questions subjectively: "Oh God, what is it to me that the witness of others attest to my intelligence and reputation since I know it to be true that he would be openly lying?" (Ha! Dex, que me vaut tiesmoignage de gens a moi essaucier pour quel raison iaie sens et valor puis que ie sai de voir quil mentiroit tout a plain; Vienna 2609, fol. 46). We have here the nub of the problem of reputation making: the difference between a subjective articulation of a "good name" and a public construction of it. By comparing the two, the respondent accentuates the process of making a name and the dominant discourses governing that process. She questions the legitimacy of reputations based solely on the "tiesmoignage de gens" (the witness of others). In her own case, the discursive constructions of others are exposed as patently fraudulent: "ie sai de voir quil mentiroit tout a plain." Yet the respondent's critique still takes the form of a question: how much is the witness of others worth?—a rhetorical question, perhaps, but one that conveys the importance of

reckoning with that tiesmoignage . The fact remains that a person's reputation, such as the respondent's, hangs invariably in the balance of the predominant public discourses.

This balance is all the more precarious when it comes to women's names. As the first Response argues, they are a frequent target of an injurious clerical amorous discourse. For the second Response , this circumstance underscores the importance of reclaiming their names. Where one text identifies the problem of verbal injury, the other attempts to alleviate such injury by taking over the function of making a woman's name. Early on in the text, the respondent states:

Pour coi ie di que dex et nature a bien moustre que li hom est la plus dingne coze que il onques feist. Et quant ie noume home, jou entent a noumer home et feme ausi cornroe il avient.

(Vienna 2609, fol. 44 verso)

For this I say that both God and nature well demonstrate that man is the most noble thing that he ever made. And when I name man, I mean to name man and woman as it is fitting.

The respondent returns to the Genesis scene. In so doing, she assumes nothing less than the divine prerogative of naming. She denominates woman along with man, thereby guaranteeing the distinct and particular existence of both parties.[24] By adopting the Genesis formula to create woman herself, the respondent claims responsibility for the female name. From the determining space of Eden, she attempts to secure women's reputations for a wider social domain.

As a result, the second Response challenges implicitly the public construction of women's names.[25] The respondent's gesture throws into question the multiple arbitrary versions of women's reputations fashioned by the predominant discourses. By calling forth the name of woman, this narrative disputes the validity of the existing ones. And it does so not only by echoing the irreproachable divine voice, but by speaking through it subjectively: "I mean to name man and woman" (iou entent a noumer home et feme). If only in the discrete space of the second Response , a woman's name is also ordained by a woman subject. Having transformed the process of naming into a divinely inspired, female, subjective affair, the second Response impeaches the public and conventional standard of women's reputations.

This problem of women's names pushes still further the first Response 's concern with injurious language. Together the two responses specify the circumstances whereby a woman's name is held hostage by the predominant discourses and made vulnerable to their vagaries. A woman's name

is both authorized product of such discourses and its most common casualty. As both respondents intimate, if a woman does not participate in the normative discursive system, she cannot exercise control over her public name. Such a person is subject to existing in name only—a name as malleable as putty. To quote a contemporaneous poem, the villein can have thirty different names, each more abusive than the last.[26] A woman may leave a similarly long trail of misshapen, distorted reputations.

Nevertheless, the second woman's response does represent a woman who articulates women's names anew. It signals some attempt to break up the discursive stronghold. The effort is admittedly small-scale, the opening little more than a crack. But the very fact that the respondent dwells on the question posed by women's names foregrounds the cardinal issue of verbal injury. Both Responses focus attention on how clerical discourse on women can operate damagingly, and how to reckon with that pattern. Their dispute involves making it a public issue—a strategy that would be exploited dramatically several generations later.

Who Is Responding?

Who is responsible for such a critique of masterly figuration? This final question concerning the phenomenon of the woman's response has elicited conflicting views. Insofar as the two Responses are cast in a subjective voice, the issue of the respondent's identity rears its head tantalizingly (Figure 10). Or should 1 say heads? With the pair of narratives, the initial respondent transmutes into another, multiplying progressively by dint of "variant authors and scribal variance."[27] In the plural or singular, the respondent figure nonetheless spurs critics to pin her down. There are those who attempt to identify her personally: her full name, her whereabouts, her biography.[28] Their detective work endeavors to link the Bestiaire respondent with a distinct individual, akin to Héloïse or, a century earlier, Constance, the learned respondent to the clerical writer from the school of the Loire, Baudri de Bourgueil.[29] There are others who, espousing the ludic character of medieval narrative, regard the subjective profile of the Bestiaire respondent as fundamentally and delightfully suspect.[30] Far from providing a lead to a historical personage, her subjectivity functions parodically, its very fictiveness mocking the critic's desire to secure provenance. As Alexandre Leupin puts it, "she" involves nothing more than a figure of speech (165–66). In fact, that a scholarly woman respondent emerges as a subject corroborates the wide range of personae in medieval vernacular narrative.

10. Another rejoinder. La Response au Bestiaire d'amour .

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f.fr. 412, fol. 236.

Photograph, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Caught between these two poles—individual mystery woman and textual ruse—analysis of the Bestiaire respondent's identity runs quickly aground. Reading "her" is restricted either to an indefinite search for one learned woman, now as ever unidentified, or an exercise in deciphering textual conundrums. The Response thus appears an isolated, extraordinary example of opposition voiced by a woman or, at the other extreme, a quintessential game-playing narrative that confirms Ovid's ploy of using feminine and masculine pronouns interchangeably to fool the public.

Are these the only possibilities? By way of proposing a different answer, I suggest listening to Christine de Pizan, who several generations later ruminated on the conventions of creating female personae. In the course of the early-fifteenth-century Querelle over the Roman de la rose , she asked:

Qui sont fames? Qui sont elles? Sont ce serpens, loups, lyons, dragons, guievres ou bestes ravissables devourans et ennemies a nature humainne, qu'il conviengne fere art ales decepvoir et prandre? Lisés donc l'Art : aprenés a fere engins! Prenés les fort! Decevés les! Vituperés les! Assallés ce chastel! Gardés que nulles n'eschappent entre vous, hommes, et que tout soit livré a honte! Et par Dieu, si sont elles vos meres, vos suers, vos filles, vos fammes et vos amies; elles sont vous mesmes et vous meesmes elles.

(Hicks, 139)

Who are women? Who are they? Are they serpents, wolves, lions, dragons, vipers, or ravenous predatory beasts and enemies of human nature whom one must plot against to deceive and capture? Read the Art of Love then: learn how to be ruseful! Take them by force! Trick them! Malign them! Assault the castle! Take care that none of the women escape from you men, and that all is accomplished shamefully! And by God, if they are your mothers, sisters, and daughters, your wives and friends, they are you, and you yourselves are these women.

As Christine reminds us, the question of identity in complex figurative texts like the Rose is ultimately a misleading one. Whether it involves depictions of women characters, the bestiary/bestial portrait, or in our case, the profile of a female subject, identity looks problematical. For when it comes to figuration in such texts, no relation of equivalence pertains, no one-way correspondence between character and author. Instead these texts involve a chiasmus: "if they are your mothers . . . they are you, and you yourselves are these women." A crossover occurs, one that in the wake of Ovidian models operates easily across gender lines. Through the mechanisms of subjective figuration and personification, a poet assumes a variety of personae that at the same time display characteristics of that poet's writing culture.[31] Not only does a poet use the subjective figure as a mask, but that mask relays cardinal features of conventional textual composition.

This distinction of chiasmus is all the more crucial when it comes to the creation of female personae. The pressure to identify those personae with the values of a male author and audience is enormous. And presuming that a female subject can only be their projection serves to obliterate her female character. In this sense, Christine's phrase "if . . . they are you, and you yourselves are these women" recalls hauntingly the Houneurs des dames formula, "femme/lui meismes ," that we considered in chapter 1. Yet there is one significant difference. The Houneurs phrase bridges the chiasmus, merging femme with lui meismes in order to extinguish the difference between them. The result is to see them in identical terms. By contrast, Christine's phrase maintains the chiasmus in order to underline the correspondences between the bestiary/bestial femme and lui meismes .

It thus emphasizes the discrepancies between mothers, sisters, daughters, and lui meismes . Christine recognizes the way clerical figuration of women reveals more about the writers and their views than it does about the women they claim to depict. Taking stock of the chiasmus enables Christine to separate out persona, person, and poet. As a consequence, it points to the social circumstances shaping all three.

This chiasmic character of female subjective identity thus leads us to consider it in relation to specific social situations. Rather than limit analysis to the fact that certain female figures constitute masks—an idée fixe for many critics—I wish to investigate how such figures are disposed. In Christine's example, associating the female personae of dragons and predatory beasts with "you men," that is, with her masterly interlocutors, marks only the first step. The critique widens to include evaluating how the masters' social situation supports such a "beastly" portraiture of women. The crossover works both ways. To answer questions like "who are women?" or "who is this woman?" means exploring the degree to which a woman's identity could be imputed to a particular social group. It involves turning the female figure around so as to gauge its social matrix. Just as Christine links the animalistic female personae to works such as Capellanus's De amore and their clerkly milieu, we can hypothesize a connection between the Bestiaire respondent and a particular setting. As Toril Moi has argued, what matters is not so much whether a particular work is formulated by a woman or a man, but whether its effects can be characterized as sexist or feminist in a given situation.[32] Even if we could attribute the Response to an individual woman, the respondent figure's social context remains crucially important. Conversely, even if we deem her identity a textual cipher, it is still embedded in a specific social matrix. Our interpretative challenge lies in assessing that context. My aim, then, is to study the respondent herself as a constituent part of a certain social logic.[33]

The Bestiaire responses afford us an unusual chance to pursue the question of a female persona's social circumstances. Because the first Response occurs in a small number of manuscripts, each with localizable features, and Response 2 in only one, these narratives can be more precisely situated in a particular milieu than many Old French works.[34] The consensus has long been that these various texts belong to the Artois and Hainaut in the north of France and in the Brabant in modern-day Belgium.[35] Compared with the Bestiaire that circulated widely in Europe in several vernaculars, the Responses seem principally linked to this northern Francophone setting.[36] What has not been acknowledged, however, is the link between the one manuscript containing both Bestiaire responses (Vienna 2609) and the mid-fourteenth-century gathering containing the Consaus

d'amours (Vienna 2621).[37] As we mentioned in chapter 1, this manuscript's provenance can be established by its dedicatory address to the duke and duchess of Brabant. Identified explicitly as Brabantine property, it was likely commissioned by the circle of Jean III and Marie d'Evreux and read first in the major Brabantine centers of Brussels and Louvain. If we consider these two manuscripts together, we find striking similarities. Layout, scribal hand, dialect, iconography, thematic coherence: their many common features suggest not only a homogeneous pattern of poetic composition but the stamp of similar circumstances of production. Both manuscripts can be associated with the same workshop. They appear to share the same context. Without claiming that the Response and the Consaus were grouped together in a single codex, we can posit a Brabantine court setting for both.

To situate the Responses in mid-fourteenth-century Brabant involves placing the respondent persona in a notoriously charged social landscape. Virtually every account of medieval Brabantine culture begins by underscoring the perennial strife that troubled its social relations.[38] "The Brabant has as many quarrels as France has vineyards."[39] This thirteenth-century proverb sums up multiple conflicts. The local nobility was struggling with an encroaching royal Capetian power. But they were also at loggerheads with their own citizens over the government of the towns. Clerical communities were deeply divided as well. They were caught between their longstanding alliance with the seigneurial caste and their growing involvement in bourgeois affairs. Their aristocratic loyalties conflicted with their support for the class of nouveau fiche. This turmoil has been interpreted largely in economic terms, the result of the ascending bourgeoisie in cities across Brabant and neighboring Flanders, Hainaut, and Artois.[40] In these terms, the story of the Brabantine Communes is one of urban emancipation based on the growing mercantile influence and autonomy of the middle classes.[41] Yet another aspect of this characteristic climate of contention in the Brabant became discernible in the arena of what we might call cultural politics. While the balance of power in matters economic and political was being sharply contested between the local duchy and the bourgeoisie, such fractiousness also impinged on intellectual life. It affected the commerce and use of texts. The authority over learning was no longer exclusively regulated by the nobility and clergy. As the bourgeoisie fought for greater municipal control, they also sought greater involvement in the world of letters and learning.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the issue of schooling.[42] In Brussels, Ghent, Cambrai, and across Picardy, the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries witnessed an important social struggle over lay education.[43] Custom granted the privilege of establishing schools and selecting

schoolmasters to the local nobility—one that, in practice, depended upon the close collaboration with the clergy. Yet there is much evidence that many municipalities across the north agitated for the right to administer their own schools independently of the nobility. Such a struggle often gave way to an outright split between the bourgeoisie and the court, between the city and the Cité —the ducal residence. Local ordinances drawn up during this period confirm the common maneuver among the urban bourgeoisie of abandoning the schools designated by the court and founding their own with clerks and masters of their own choosing.[44] Action was taken to wrest control over education from the nobility and thereby to intervene strategically in the arena themselves. At the time of the Brabantine Responses , the bourgeois was challenging the clerk and the duke for the management of rudimentary lay literacy. Behind their representations of a laywoman debating with a master, then, we might well divine a controversy between these various factions arising from the bourgeoisie's mounting activism in the world of letters.[45]

Where does the woman respondent figure in this picture? In most surveys of lay literacy, the claim has been repeated ritually that the spread of Aristotelianism and scholastic culture proved disadvantageous for women.[46] Put another way, the high-medieval practices of intellectual mastery and women's learning were not easily compatible. In the case of Brabant, where Aristotelian treatises were in vogue at the ducal court, the climate seemed hardly favorable to the development of women's intellectual life.[47] We have only to recall the miniature from the Consaus manuscript depicting the duchess of Brabant (Figure 4). Side by side with the duke, she is still not portrayed as an equal participant in the dialogue with the master. While the duke holds a book, the marker of his involvement in the master's erudition, the duchess has a scroll inscribed with a love song (amour amoureces ). Associated with amorous refrains alone, she has limited access to their debate. She is effectively left out of the duke and master's rarefied academic discourse.

Yet let us not forget that out of the same milieu comes the image of the respondent equipped with the tools of textual culture (Figure 7). Not only do we find the commonplace repressive image of the woman who approaches the master only in a diversionary way, but also the surprising one of the actively engaged literate woman. The fact that these manuscripts present both images is telling. Indeed, the fact that their Brabantine communities could accommodate them together leads me to suggest that our respondent persona exemplifies the tensions concerning lay learning in general and the training of laywomen in particular. Far from confirming an existing situation or intensifying a fantasy, the respondent persona galvanizes the

conflicting attitudes prevailing in fourteenth-century Brabant. She recapitulates the differences—promising and limiting—that made up the dispute over the regulation of lay instruction and the laity's access to texts.

What has often been overlooked is the way the controversy over education—itself the consequence of considerable social turbulence—changed the prospects of laywomen's training. Bourgeois militancy tested the established categories that reserved the practices of writing and debating for the clerisy and the male nobility. The campaign to diversify pedagogical opportunities across social lines could also translate into changed opportunities for women across classes. With the laicization allied to the rise of urban culture, a space opened up for noble and bourgeois women that was not as tightly surveyed as the hermetic enclosure of courtly society.[48] And the moral necessity to discipline women's reading to pietistic works was conspicuously absent in the heady context of fourteenth-century Brabant. We find no prescription comparable to those issued in the Capetian court.[49]

Several points are in order here. If we take a cross section of the urban landscape in northern France and Brabant at the time of the Bestiaire Response , we find that a primary school for girls was commonly established at the same time as one for boys. In Brussels, one seat of the Brabantine duchy, a statute survives that details the foundation of a girl's school (Stallaert, 101). This school made provisions for upper-level instruction. Not only could laywomen learn to read and write, but they were able to pursue studies beyond the rudiments of Donatus's ABCs, notably in ars dictaminis (the art of composition). Whereas these skills hardly point to the sophisticated labor of scholastic commentary, they nonetheless do associate a wider group of laywomen with a textual practice beyond that of mere passive reading and recitation.

That such an opportunity existed is borne out by the incidence of city women who owned books. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there are cases of those who possessed a basic collection of romances and religious works—a pattern that surely contributes to the early-modern reputation of Flemish bourgeoises as linguists and bibliophiles.[50] One exemplary case, several generations earlier than the Response , involves a certain Maroie Payene of Tournai who in 1246 willed to her children grammar books, a Marian devotional manual, and a copy of the Roman du chevalier du cygne .[51] Her testament makes clear the range of texts in her possession and their importance to her. The fact that she transmitted them legally, together with her property and jewelry, emphasizes just how committed she was to her personal library.

If we can account for laywomen as students and as bookworms, it is hardly surprising to discover that in this context they were also emerging