Conclusion

Late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French writers on architecture found much to admire in the treatment of details in the work of their sixteenth-century predecessors, but such writers were little inclined to recommend to their readers the 'assemblage', or the manner of combining decorative forms seen on important Renaissance buildings in Paris. In the annotated 1673 edition of Louis Savot's L'Architecture Française des bâtiments particuliers, which had first appeared in 1624, François Blondel wrote

. . . the taste of the times in which this author was writing was to crowd the façades of buildings, not only with columns and with pilasters, but also with cartouches, with masks and with a thousand other ornaments composed in strange combinations, and they had not yet their eyes accustomed to the natural and simple beauty of fine architecture which pleases purely through its symmetry or the satisfying relationship of the parts, one to the other and within the context of the whole, and by the correct mixture of suitable and well-adjusted ornamental parts which gives us such pleasure when looking at some of these majestic ruins of antiquity.[1]

François Blondel (1617-1686) was the first of the Professors of the Académie Royale d'Architecture and the leading exponent of rationalist orthodoxy, and in his published lectures the Cours d'Architecture issued in five parts between 1675 and 1698 he insisted that the valid rules of architecture could be learnt only from the study of the buildings of classical antiquity, with the work of Italian Renaissance architects given an honourable second place in his hierarchy. Nowhere in Blondel's copious writings did he recommend his students to study the Royal houses of sixteenth-century France. The little said by late seventeenth-century critics about the palaces and châteaux of the previous century only shows their exasperation with all aspects of their planning and decoration, and which would be condemned or dismissed as 'gothic'.[2]

The most influential of eighteenth-century architectural teachers and critics was François Blondel's nephew, Jacques-François Blondel (1705–1774). In the four folio volumes of his Architecture Françoise published in 1752, 1754 and 1756 he argued at length in defence of the French manner in architecture, in which he traced the renaissance of good architecture in the

reigns of François I and Henri II, a process which reached its greatest flowering and final maturity under Louis XIV. Despite a more sympathetic attitude than his uncle's towards the work of mid sixteenth-century architects, Jacques-François Blondel could not suppress his feeling that the architecture of a Lescot or a de l'Orme had been a false dawn for the classical style in France. Only with François Mansart, whom he crowned 'God of Architecture', were all of Blondel's requirements of comfort, convenience and decorum fully satisfied, for in Mansart's work Blondel saw the good planning and the fresh, original and harmonious use of classical ornament which were the true virtues of the French national style. Jacques-François Blondel was keen to promote interest, and to elucidate by careful description and analysis, the particular qualities of the French manner as practised by the distinguished architects of the sixteenth, seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, but where he developed his propaganda into stylistic analyses of individual buildings, he found himself in the invidious position of being both the advocate and the detractor of the Renaissance school in France. Of Lescot's Louvre he wrote both approvingly and disapprovingly:

. . . This building originally having been begun with the delicate order, and previously only had two floors crowned by an attic, as it has been executed in the greater part of this court, following the designs of Pierre Lescot, who nevertheless ought to have put the Composite order on the ground floor and the Corinthian above, as an expression of the most declicate and the Order which is the most perfect possible for putting on the upper part of the building.[3]

On the next page Blondel lists his likes and dislikes more fully:

. . . the defective proportions of the ground-floor arcade, when compared with the diameter of the columns, and with the window openings of the first floor; just as we will be bound to notice many other short-comings, the smallness of the niches, the multiplicity of architectural members, the returns in the entablature too often repeated, the repetition of the projections, the breaking of the friezes and the architraves, in order to put inscriptions there which cannot be read, the pointless horizontal division of blocks at the wall joints, the oculi which are a foretaste on the outside of the irregularities in the arrangement of the inside, the disparity of the door frames and of the windows which disturb the balance of the decoration, the repetition of plaques and of medallions too poorly arranged, which introduce too many small distracting details, which precludes any domination by the orders which always ought to have the first consideration, and to appear to preponderate over the remainder of the composition. Finally, we shall be constrained to recall the disproportion which one notices between most of the sculpture and

the Architecture; so many condemnable discords, and so many breakings of the rules which show that the Sculptor was not directed by the Architect, and the latter neglected the spirit of propriety, without which one cannot achieve the best results.

Accordingly, we will pass over these mistakes, and we will stress the admiration which one should have for each of these parts, which are such masterpieces when considered individually, whether for the beauty of such a great number of details, or for the brilliance of the hand which carved the ornaments, which enrich each architectural feature, and which deserve the greatest praise. Likewise, we acknowledge also that it is the genuine beauty of these various parts we would wish had been done with a greater overall economy in the ornaments, and a more general harmony between the whole and the parts. However, despite the irregularities of which we have been speaking just now, there is hardly a building in France more likely to inspire the proper taste in ARchitecture than the scrutiny of this moment; above all when informed of the rules of the Art, one will be able to judge the worth of each of its beauties, and to make judicious use of them on one's own work; this being the only way of gaining knowledge of that which is truly beautiful, to purify one's compositions, and to avoid the indistinct imitation of the works which have preceded us.

Many of Blondel's criticisms of Lescot's Louvre are expressed poorly and are difficult to follow. Few can understand his meaning when he states, ' . . . The oculi which are a foretaste on the outside of the irregularities in the arrangement of the inside . . .' Modern architectural historians prefer to describe and cautiously to analyse Lescot's Louvre, and Blondel's value judgements would be thought unreasonable and absurd if pronounced by a contemporary critic whose views could not stem, as did those of Blondel, from a living and a developing classical tradition with accepted mathematical rules and aesthetic aims. The problem of Lescot's Louvre, or of de l'Orme's Tuileries, is that they appear to have little context within Western European architecture of their time, and stylistic sources of parts or of the whole of their compositions have not been easily sensed, and never proven. The value of Blondel's strictures and compliments of Lescot's Louvre is that the eighteenth-century critic was fully confident of his rectitude in matters of design and taste, and he was sympathetic to the early classical style in architecture in France. It is almost certain that Blondel was only the most specific of a long line of critics of Lescot's seminal work, which extended back to the sixteenth century. The same points might have been made by ' . . . those who are expert in the art find it [Lescot's Louvre] full of errors, both on the outside and on the inside . . .' mentioned by Blaise de Vigenère writing about 1590. Twentieth-century writers on Renaissance architecture have been neither qualified nor inclined to criticize a building for deviations from Vitruvian pro-

136

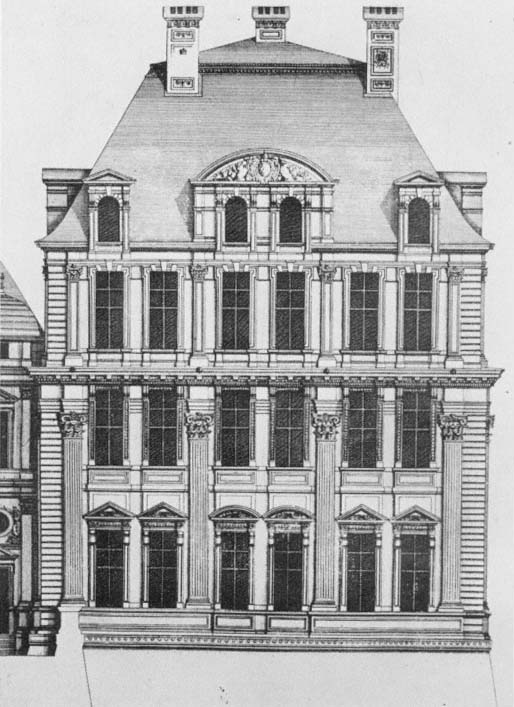

The Pavillon de Flore. West elevation. Engraving by Jean Marot, c. 1660.

137(a)

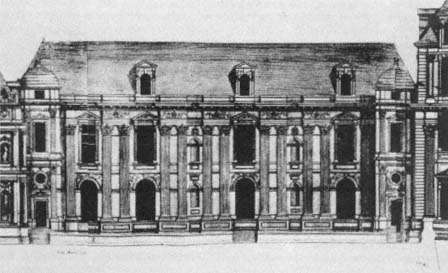

Tuileries 'galerie'

Henri IV façade

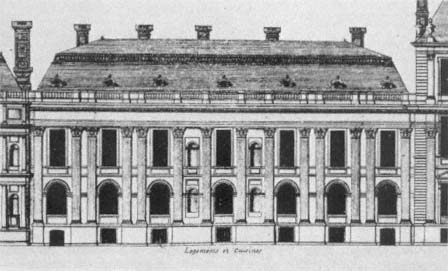

137(b)

Tuileries 'galerie'

Le Vau façade.

portions, or for inaccurate or unclear quotation from antique architecture.

Seventeenth- or eighteenth-century examples of architects quoting from the decorative motifs of Lescot's Louvre in their own designs, or in Blondel's words ' . . . judicious use of them in one's own work . . .' are easy to find. The grandiose Hôtel d'Avaux, now the Archives de la Ville de Paris, of 1644 to 1650 by Pierre Le Muet has ground-floor windows,

recessed in arches and with mouldings which were copied with few alterations from the Louvre. Lescot's window mouldings reappear frequently throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries on the elevations of haut-bourgeois and aristocratic houses. The most interesting example of the reform of a sixteenth-century style by the orthodoxy of the later seventeenth-century is seen at the Tuileries, as remodelled and completed by Louis Le Vau from 1664 to 1666.[4] The 'galerie des Tuileries' built under Henri IV between 1603 and 1606, which connected the Bullant pavilion with the Pavillon de Flore (Fig. 137), had a garden front with an irregular rhythm of 1:2:4:4:1 of giant paired-pilasters between the windows, and had first-floor windows whose pediments broke into the frieze. Amongst Le Vau's 'corrections' was the introduction of an uninterrupted frieze cleared of relief decoration, and he reorganized the pilasters into a symmetrical arrangement. This example of the domination of the orders, unfettered by distracting detail, would have met with Blondel's approval. Above the arcade of the de l'Orme wing of the Tuileries, Le Vau had the dormers pulled down and replaced them with a full storey with an attic (Fig. 126b). Le Vau retained de l'Orme's tapered pilasters on the first floor, a compromise which provoked Blondel to complain that Le Vau was meddling with an imperfect elevation, rather than redesigning it.

Blondel's most persistent complaint is that sixteenth-century Parisian architects did not use a module, the diameters of columns or the width of pilasters, as the basic unit with which all proportions and ratios of a façade should be calculated. On this principle he disliked both the Fontaine des Innocents and the de l'Orme wing of the Tuileries which, he went so far as to say, ought to be demolished to make way for a building in the proper taste.[5] Modular architecture was not a concern of Lescot, of de l'Orme or the architect of the Hôtel d'Angoulême, as it was a preoccupation with Italian fifteenth- and sixteenth-century architects, and which became an ingrained principle at the Académie Royale d'Architecture and with Palladians.

Partly as a reaction against the austerity and stylistic economy of much later eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century neo-classical architecture, many historians and architects of the second half of the nineteenth century admired the idiosyncratic and varied French Renaissance architectural styles without their consciences being troubled by the ghosts of Vitruvius or Blondel. Country houses in the French Renaissance style were built not only in France, but also in England and Germany. This nostalgia did not extend to a critical examination of the development of the classical style in ecclesiastical building, nor to a French Renaissance revival in church building. Individual monuments found their historians, but the churches of sixteenth-century Paris, with the sole exception of the Goldsmiths' chapel, were planned in the Gothic tradition, and their decorations are so unusual and disparate, that an analysis of them as a group has never seemed to be worth attempting.

138

Cloister of the Célestins. Engraving c . 1790.

In the 1650s Sauval could count more than three hundred churches in Paris, and of these only four of the largest churches were begun or largely built during the sixteenth century.[6] Sauval shared many of the stylistic prejudices of the Blondels in scorning the application of classical forms to unsuitable 'gothic' contexts. Only in the cutting of some of the Corinthian pilaster capitals could Sauval find anything to admire in Saint-Eustache, the largest of France's Renaissance churches, which was begun in 1532 but not completed until 1632.[7] The most spirited abuse of Saint-Eustache was written in the nineteenth century by Viollet-le-Duc who dismissed it as ' . . . a monument which is badly conceived, badly built, a confused accumulation of bits taken from here and there, unrelated one to the other and without harmony, a kind of gothic skeleton clothed in Roman rags and tatters stitched together like the pieces of a harlequin's costume'.[8] Mystery surrounds the identity of the man or the group of men who designed Saint Eustache, and no architectural writing survives from the time of the building's inception to give an insight into the thinking behind this unique and eccentric use of columns and pilasters, and whether

it was an unwitting or forced marriage of distinct and unrelated styles.

The only ecclesiastical buildings whose forms allowed for a coherent use of classical ornamentations were the cloister of the Célestins of 1541 (Fig. 138) and the Goldsmiths' chapel begun in 1550 (Fig. 139). The destruction of the Célestins cloister during the first decade of the nineteenth century meant the loss of the most admired Renaissance building in Paris. Sauval remarked: 'The ceilings of the cloister are arranged with great skill. It is the most beautiful cloister; and the good architects do not shrink from saying that it is the finest piece of architecture in Paris.'[9] It would be most interesting to know the names of the 'good architects' referred to by Sauval, and the stylistic features which might be admired by an architect of the generation of Lemercier, a Mansart or a Le Vau. Testard's engraving is the only record of the cloister's appearance, and shows that its form was in the medieval tradition (it was probably rebuilt on the foundations of a fourteenth-century structure), but with the decoration thoughtfully and skilfully adapted. The three principal orders, the Doric, the Ionic and Corinthian were combined in a most unusual way, with giant Doric pilasters facing the cloister walk, full Ionic columns for the outer faces of the piers, and pairs of diminutive Corinthian columns for the arches of the arcade. When compared to Saint-Eustache, begun less than ten years before the Célestins cloister, the stylistic advance looks considerable, and the explanation may lie in the long-standing association of the Order of Célestins in France with the Royal household dating from the reign of Charles V.[10] A contract for the masonry of the cloister of April 1541 has been discovered, which names Pierre Hannon as the master mason for the work, but does not give the name of the architect.[11] On 15 November of the same year Jean Cousin signed a contract for six statues of saints for the cloister, three of which can be seen in Testard's engraving, under the pediment on the east side of the cloister.[12] Jean Cousin the Elder (c . 1490–1560) was the leading native artist of his generation, with a greater range of abilities than any of his fellow painters,[13] and he could well have been the architect of the cloister. The vaults of the cloister walk were of wood, and reports of their outstanding quality strongly suggest an attribution to Scibec da Carpi, who had been established in Paris for at least ten years before the first of his major commissions from the Crown.[14] The Célestins cloister contains few points of comparison with Lescot's architecture at the Louvre, but a common independent spirit in the use and organization of the orders is seen in both buildings, unaffected by the beginnings of the proliferation of architectural books.

Only the façade of the Goldsmiths' chapel survives, and it is in a much mutilated condition, but when fully finished by the mid 1560s, with stained glass designed by Jean Cousin, and with an altar with statues of the Trinity, the Virgin Mary and Saint-Eloi by the eminent Germain Pilon, the Goldsmiths' chapel must have been one of the most impressive small jewels of French Renaissance art.[15] Amongst project drawings for the

139

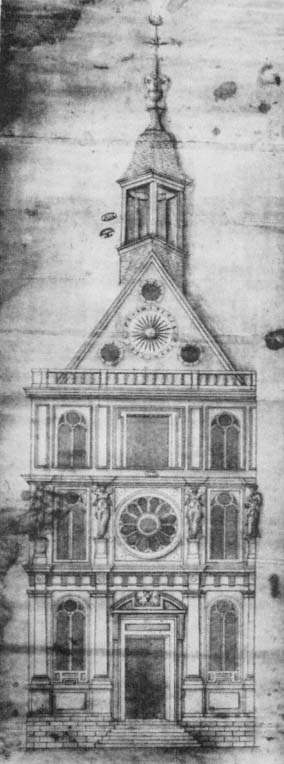

Goldsmiths' chapel. Façade project.

140

Doorway design by Philibert de l'Orme,

from the Architecture f° 252.

141

Doorway at Saint-Nicolasdes-Champs,

1570/1580.

chapel in the Archives Nationales are two designs for the façade, both of which consist of three tiers. The drawing which is thought to be the earlier of the two façade designs has a correct succession of applied Doric, Ionic and Corinthian attached columns.[16] . The other surviving façade design (Fig. 139) is a brilliant, original essay in the use of the Doric order in the context of a tall narrow elevation. Here the architect has avoided the risk of breaking the classical rules of proportions by using an order of grouped Doric pilasters on the ground floor only, with caryatids on the middle storey and panels for the vertical accent of the top storey. This allowed him to reduce significantly the height of each succeeding tier, which would not have been possible in a composition using all three orders correctly. Designed on the basis of simple proportions and ratios (for example the height from the ground level to the Doric cornice equals the height of the second and third tiers) this project is a clever and elegant solution to a problem which had vexed many fifteenth- and sixteenth-century architects, of how to articulate a church façade with properly proportioned classical ornament.[17] The solution proposed in this drawing is more sophisticated than any classical church façade in France either before 1550 or of the later decades of the sixteenth century. The design of the Goldsmiths' chapel as built has traditionally been credited to Philibert de l'Orme, and no serious objections have been raised to contradict the attribution. One of the drawings in the Archives Nationales, showing a section of the chapel, with its architecture of Doric pilasters and panels for the upper tiers, has an inscription in Italian. It records the writer's approval

142

Doorway at Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois,

1570/1580.

of the use of the Doric 'after careful consideration'.[18] It is certainly Serlio's handwriting, and it is most unlikely that Philibert de l'Orme would have wanted to see his designs vetted by the Italian, which suggests that it was the patrons who were keen to have a good building in a correct classical style, and who sought a second opinion from another Court architect.

Very little can be said of Parisian ecclesiastical architecture during the troubled 1560s, 1570s and 1580s. Important work was carried out on the interior of the church of the Augustins and on the fabric of the Cordeliers during the reign of Henri III,[19] and the small chapel seen in Sylvestre's view of the Louvre garden (Fig. 128) may be the building designed by Baptiste Androuet du Cerceau for the King in 1582. A woodcut from Philibert de l'Orme's Architecture showing an arch which he had designed for the festivities at the Tournelles in 1559 (Fig. 140) was imitated on the churches of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs and Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois (Figs 141–142). The differences between the woodcut and the doors of Saint-Nicolas and of Saint-Germain cannot properly be called reinterpretations of de l'Orme's design, for none of the alterations can be described as corrections following the recommendations or instructions of another architectural writer of the period. The designer of both the Saint-Nicolas and Saint-Germain doors closely imitated de l'Orme's design up to the frieze, above which a change to a full-triangular pediment was introduced. De l'Orme might have been gratified by the re-use of his woodcut design for two church doorways, but he could not have foreseen that this composition, of relatively minor importance within the context of his

treatise, was to become the architectural 'leitmotif' on a monumental scale of the western half of Henri IV's Grande Galerie of the Louvre and of the Petite Galerie of the Tuileries.[20]

The criticisms of later generations of architects, or the wrath of the orthodoxy of architectural teachers, are more likely to encourage instead of discourage a fascination with the distinctive and unique qualities of sixteenth-century Parisian architecture. During the course of the twentieth century there has been a considerable growth in interest in the art of the later Renaissance in Italy and in Northern Europe, and few modern art or architectural historians are persuaded by Wölfflin's notion of the later sixteenth century as a period of decline or stagnation. The use of the term 'mannerism' to characterize the stylistic refinement and iconographical complexity in much Italian, Netherlandish and German painting and engraving, can only be used with very great caution when writing on architecture. The term 'maniera' first appeared in Cennini's Libro dell'arte , written about 1390, where he advised a young painter to copy the work of an established artist in order to arrive at an understanding of the technical and stylistic secrets of a master. Over four hundred years later critics and painters of the Romantic period were speaking of 'mannerism' as an excuse for a preoccupation with art and technique in preference to the study of nature.[21] Mannerism in later sixteenth-century French architecture has been more associated by modern writers with excessive use of ornament than with the more significant sense of national artistic and stylistic independence, which can be sensed in Lescot's Louvre, and which is made clear in the writings and in the architecture of Philibert de l'Orme. The spirit of affinity with, but independence from, ancient culture is most clearly stated in the poetry and prose of the second and third quarters of the century.

Joachim Du Bellay's famous Deffence et Illustration de la Langue Francoyse was first published in 1549, and part of the special interest of the text is Du Bellay's acknowledgement of the imperfection of the French language in comparison to Greek or Latin. He believed that inadequate or attempted literal translation of ancient poetry could be of little use, or even could harm the reputation of the original texts, and above all could be of little service to the creativity of modern poets and writers. Du Bellay used an architectural metaphor in a passage where he ridiculed the absurdity of those who wished to rebuild the achievements of ancient civilization by using scattered remains, for such an approach to writing or to other liberal arts precluded the full control of the creative intellect and inhibited the development of an original conception.[22] In Du Bellay's view the gifted artist is one who is the master of his erudition, and imitation is a symptom of a perverse use of knowledge. The architects of Renaissance Paris created new styles for Royal palaces, aristocratic and haut-bourgeois hôtels , in which each aspect of classical decorative design was thought out afresh. It is not possible to estimate when the feeling arose that a classical architectural

manner should be encouraged and developed in France which would be a distinctive national style. In creating a French order for the Tuileries in the early 1560s, de l'Orme certainly was not the instigator of a revised language of architecture or national style. The virtues of the French manner as described by Jacques-François Blondel were based on functional practicability and stylistic restraint and harmony. The mid sixteenth-century pioneers of new classical styles cannot be blamed for ignorance of architectural orthodoxy, in an age when such concepts hardly existed in any of the important artistic centres. The great variety of Parisian Renaissance architecture makes the interpretation of these buildings a part of a wider insight into a society in the process of profound social, political and cultural change.