19—

Waiting in the Wings

From 1955 to 1956, the 84th Congress was concerned with tension in the Formosa Strait, de-Stalinization of the Soviet empire, revolt in Poland and Hungary, and war at the Suez Canal.

As the new year began, the New York Times named Bill Knowland one of the ten most influential members of Congress:

The hierarchic heir of the late Senator Taft, 46-year-old William F. Knowland of California is a man with an unquestionably sincere mission to harden our policy toward Asian communism—and one whose convictions have unquestionably damaged his mission as GOP leader. Without great flexibility, and without the seemingly indolent, casual grace in action of his opposite number, Senator Johnson, Knowland for all that retains great power in the Senate.

More nearly than not, he still articulates most of the basic views of the orthodox Republicans who still outnumber the "Eisenhower Republicans." His leadership is one of open thrust and parry; one of recurring, more or less ad lib accommodations with now one and now another of the Republican factions. Large, solid, stable and deeply courageous, he is a good "Senate man," regardless of whether he is a good Administration man.[1]

The new year also was to end his reign as majority leader. The balance of power had shifted to the Democrats, who now held a 49-to-47 edge in the Senate.

The shift did not silence but seemed to exacerbate the tirades of the now-discredited Joe McCarthy, who was bitter over the Republicans' loss of control of the Senate. While that doubtless upset Knowland, at least he didn't blame it on Eisenhower. Not so McCarthy; he com-

plained that Eisenhower's failure to support Republican Herman Welker of Idaho, who lost to the young internationalist Frank Church, had cost the Republicans control of the Senate.

It had also cost McCarthy his bully pulpit—the chairmanship of the Senate Government Operations Committee, which he had used as an investigatory panel. He would not have at his disposal any weapon to attack those who voted to censure him. "This year, I believe for the first time in history," McCarthy raged on the Senate floor, "we saw the President trying to purge a member of his own party after the primary. . . . The control of the Senate today by the Democrats is the direct responsibility of a so-called Republican president. Eisenhower did not do it inadvertently. He did it deliberately. He knew what he was doing."

Bristling, Knowland hauled his large frame from his chair and rose to defend the president against the man he had tried to shield from censure. Knowland noted that Eisenhower had made speeches for Welker in Idaho and had written laudatory letters in support of Welker's re-election. No other senator defended the president. Later McCarthy stepped up the attack, claiming that "the White House palace guard encouraged the raising of money in New York to be sent into Idaho to defeat Welker and elect a Democrat." At that point, Knowland read from a letter Ike had written Welker, quoting Eisenhower's praise of his fellow Republican: "little recognition has been given to the many times you have wholeheartedly supported the Administration in advancing key parts of its program." Then he told McCarthy, "I don't want any unfairness to be implied to the President of the United States."

As Associated Press reporter Jack Bell put it, "This was the Knowland of responsibility, a grim-visaged mastodon with convictions and the courage to back them up. Here was Taft's unwanted legacy to the Eisenhower administration, a man who would be fair to friend and foe, but who was not more likely than Taft to wear any man's collar, including the President's. Armed with a fierce integrity and a deep devotion to his country, Knowland would plow his own furrow. If it ran parallel to administration efforts, well and good. If it did not, that was regrettable, but not something to worry about for long."[2]

On the morning of January 18, 1955, Eisenhower and his press secretary, James C. Hagerty, met to discuss a speech Knowland had given

the previous night in Chicago, during which he had ignored the president's admonition against attacking the United Nations. Knowland had lashed out at Dag Hammarskjold, the UN secretary general, for his failure to negotiate a return of the eleven airmen still held by the Chinese Communists, and had insisted that the United States ought to take action on its own to get them back. Knowland warned the president that any "appeasement of the Communists will be subjected to not only the most searching scrutiny by the American Congress but by a far more potent and solemn referendum of the American people in 1956."

Three days before he gave the speech, Knowland had met with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles over the fate of the airmen. "I assured him that no 'deal' was contemplated involving recognition, UN seat, trade or like subjects," Dulles wrote in a memorandum of his conversation with Knowland. "Senator Knowland expressed considerable dissatisfaction at developments, although he did not press for any drastic action." The California senator told Dulles he realized that military action might not free the airmen and could, in fact, harm them; but he was also worried about America's self-respect. "He said he agreed with me that we should be 'slow to anger' but that does not mean that we should never be angry," Dulles said. Knowland said that perhaps it was appropriate and would be helpful if he spoke out vigorously against the continued holding of the fliers. "I said I saw no serious objection to the expression of such a sentiment," Dulles said, "although I hoped that he would not urge specific drastic action, which, in fact, the Administration would not be disposed to take."[3] Thus while Eisenhower was angry with Knowland for attacking the United Nations, his own secretary of state did not object to Knowland's tirades, at least before the fact.

At the beginning of 1955, the Communist Chinese launched a number of offensives against a string of islands in the Formosa Strait, including the Tachen Islands and the little island of Yikiang, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff demanded that Eisenhower take some action. When the president argued that the islands were not strategically important, Knowland was incensed. However, Ike agreed that if the Chinese should launch an attack on Quemoy or Matsu, two strategic islands that were stepping-stones to Formosa, the United States would act. On January 24, the president delivered a message to Congress calling for passage of the Formosa Resolution, proposed a few months earlier,

which would give him authority to protect the island that served as headquarters of the Nationalist Chinese. Although Eisenhower said he did not need this authority from Congress, he wanted to make it clear to the Communists that the full force of the U.S. government was behind his move.

At a meeting with Eisenhower on January 25, Knowland told him that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was likely to report out the Formosa Resolution that day. Eisenhower told Knowland, "You know, Senator, sometimes we are captains of history. Formosa is a part of a great island barrier we have erected in the Pacific against Communist advance. We are not going to let it be broken. . . . We just can't permit the Nationalists to sit in Formosa and wait until they are attacked, and we just can't try to fight another war with handcuffs on as we did in Korea. If we see the Chinese Communists building up in their forces for an invasion of Formosa, we are going to have to go in and break it up." Knowland replied that he believed the president would have overwhelming Senate support for the resolution. He noted that William Langer of South Dakota would probably vote against it, but that while Estes Kefauver and Wayne Morse would make long speeches against it, they would vote for it.[4]

The resolution went so far as to give the president the authority to defend "related positions and territories now in friendly reference to Quemoy and Matsu." Some Democrats tried to get that provision stricken from the resolution, but they were beaten back. To quell their discontent, Eisenhower sent a dispatch to Democratic Senator Walter George of Georgia stating that the president and only the president would make the decision whether to commit American forces to any attack on the mainland. Senator George then declared, "I believe that President Eisenhower is a prudent man. I believe that he is dedicated to a peaceful world. I believe what he says, and I am willing to act on it."[5] With that, most opposition disappeared. The Senate passed the resolution 83-3, and on January 29 Eisenhower signed it. Senators Langer, Morse, and Herbert Lehman of New York were the three opposing votes.

It was a major victory for Knowland, who told Newsweek magazine that Quemoy and Matsu were the last areas of defense between the mainland and Formosa. "To use a football analogy, the defense cannot wait until the team with the ball crosses the line of scrimmage before resisting. By that time, it may be too late to stop the advance," he said. But the resolution, he thought, would also decrease the danger

of war, "although it must be clearly recognized that the Communist world holds the key to the final answer."[6]

Reflecting on that resolution in 1967, Knowland would call it a necessary act to tell the Communist world that the United States was willing to draw the line. He believed that had the United States taken similar action it might have averted World Wars I and II as well as the Korean War. "We felt, to our national interest, it was better for any potential aggressor to understand thoroughly that if an attack was made upon Formosa that we considered to be vital to our Pacific line of defense which ran from Japan through Okinawa to the Philippines and anchored on Singapore and Australia, that a breach of that line would be contrary to our best national and international interests." The resolution proved successful, he noted, for the Communist Chinese had made no further attempt to breach that line.[7]

Hostilities in the Formosa Strait were heating up again, as the Communist Chinese were making threatening overtures toward Quemoy and Matsu while Eisenhower once more was trying to determine whether the United States should be put in a position to defend the Nationalists. In March 1955, Admiral Robert Carney leaked to the press a story that the Red Chinese were set to invade the strategic islands and that Eisenhower was going to order a bombing of mainland industries.

If that was Ike's plan, Knowland was all for it, but he wanted a clearer commitment from the White House. He launched a vigorous attack on the Eisenhower administration for seeking appeasement rather than risk war with the Chinese. At that point, Senator George leaned over to urge Lyndon Johnson to answer "that wild boy who is trying to force Ike into a flat commitment to defend Quemoy." Although Johnson agreed with Knowland, to keep harmony in the Democratic ranks he rose and attacked Knowland for proposing an "irresponsible adventure."[8]

Then in a surprise announcement on April 23, Chou En-lai said that his government was willing to negotiate peace with the United States. But John Foster Dulles, worried that the Chinese were "playing a propaganda game," put three conditions on the negotiations: that the Nationalists be included as equals in the talks, that all American prisoners in China be released, and that China accept the United Nations' offer to participate in the talks. Chou rejected the conditions, and on April 26 Dulles modified them. He said a cease-fire was necessary in the Formosa Strait and that the United States would not talk behind the Nationalists' back. Eisenhower was even more conciliatory.

On April 27, Knowland spoke with Dulles. The secretary had an aide listen in on all telephone conversations concerning State Department business and take notes of the conversation, and those notes record Knowland questioning how Dulles could back away from the three conditions he had set forth for negotiations to proceed: "He does not see how the Sec. can negotiate a cease-fire without affecting the Nationalists and realistically he does not think the Chinese Communists will be interested in negotiating without a down-payment of the offshore island. The Sec. said he does not think so either."

Although Dulles claimed that his follow-up statement was a restatement of his original policy, "K. was most upset. He is concerned and discouraged and shocked at what appears to be a reversal of the weekend. The Sec. said he did not think it was a reversal. . . . K. thinks once we get into this kind of a pow-wow he'll be surprised if we are not prepared to give not only our shirt but someone else's and we will be accused of running out." Knowland also expressed anger about being kept in the dark about the latest policy toward Communist China, which he had first read about in the New York Times . Dulles said "he would not take back what he said, but did not know the press conference would take the turn it did."[9]

That evening Dulles invited Knowland and colleagues Bourke Hickenlooper of Iowa and Alexander Smith of New Jersey to meet with him at 6 P.M. at his home. There, Dulles explained that the Communist Chinese were building up their airfields, which would give them air dominance of Quemoy and Matsu "in the absence of an all-out United States atomic attack." But the president was reluctant to allow the Nationalists to bomb the airfields with U.S.-made planes, because "this would seem in the nature of 'preventive' war and make us seem responsible for the hostilities which would doubtless ensue." He also said that Eisenhower was reluctant to use atomic weapons because they would cause heavy casualties. "This might alienate Asian opinion and ruin Chiang Kai-shek's hopes of ultimate welcome back to the mainland," Dulles warned.

The secretary of state said diplomacy, not force, should be used "to avoid a misfortune of considerable proportions in relation to the coastal positions which might either be lost or only held at prohibitive cost." He told the senators that friends of the United States had put pressure on Chou to seek the negotiations and that a "complete turn-down by the United States would alienate our Asian non-Communist friends and allies." Dulles pointed out that the Nationalists had already agreed

under their defense pact with the United States not to attack the mainland unless they were attacked or unless the United States agreed. Therefore, he claimed, he only had to persuade the Communists to accept a cease-fire.[10]

The Republican Senate leader was not convinced; he did not trust the Communists. "I for one do not believe the Communist leopard has changed its spots," he said on May 5. "Their objective has been, is, and will continue to be the destruction of human freedom." Calling Dulles's three original conditions for the negotiations reasonable, he expressed particular disturbance at China's refusal to allow the Nationalists into the talks: "History teaches us that prior experience of great powers negotiating in the absence of small allies has not reflected great credit upon the large nations and has been disastrous to the small ones." Once again, he referred to Munich with its impact on Czechoslovakia and to Yalta with its impact on Poland and the Nationalist Chinese. "That we are at one of the great turning points of history I would not deny. Whether it is a turn for the better or for the worse only time will tell."[11]

In early August 1955, the Americans and the Chinese opened negotiations that were to last more than a year. Not long after the talks began, the Chinese freed the American fliers. It wasn't until January 21, 1956, that the State Department released a summary of what had taken place. About all that had been accomplished was an agreement not to use force in Sino-American relations. The Formosa Strait issue remained unsettled. On the one hand, the United States argued that the renunciation of force was meaningless so long as the Communists maintained their threat against Formosa; on the other hand, the Chinese insisted that Formosa belonged to the Chinese and was outside of the agreement. The stalemate led the Chinese to suggest that the talks continue at the foreign minister level, but Dulles refused, feeling this to be an implicit recognition of the People's Republic of China.

While the talks were going on, the hostilities in the strait had quieted and the immediate danger had passed. The talks had led to no firm agreements, but then no war had broken out either.

The friendship that Knowland and Lyndon Johnson shared would show its best side after July 2, 1955, when Johnson suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland. "I

sent word to Senator Johnson as soon as I could that he need have no concern about any advantage being taken of his absence," Knowland said. "But I did no more really for Johnson than I would have expected he would have done for me had the situation been reversed."[12]

In a July 12 letter to the Senate majority leader, Knowland wrote that Johnson's stand-in, Senator Earle Clements of Kentucky, was doing a fine job and that he was pleased that Johnson's health was improving. "As your 'older' or is it 'younger' brother, I want to give a little gratuitous advice which I probably wouldn't take myself. Remember that the most important thing . . . is to give first priority to the complete restoration of your health. When one has been as active as you have, it is difficult not to get restless and worry about things which should or should not be done. Avoid doing this." Knowland then proceeded to fill Johnson in on legislative action and noted that he was going to meet with Clements to discuss bills before the Senate.

On September 27, Johnson wrote Knowland that his friendship had sustained him during his recovery. "I will never forget the long letters that kept me informed of what was going on in the Senate," Johnson said. "I will never forget the generosity with which you gave of your time and your abilities to finish the work we had started together. I will never forget your visits and how much they lifted my spirits. I could not thank you adequately at the time, but I want to say now that I have never known a man whose integrity I respected more or whose friendship I cherished to any greater degree. In the Senate we may sit on opposite sides of the aisle but in personal affection there will never be any dividing line."[13]

The political campaign began heating up in early 1955, primarily because Eisenhower was hinting that he might not run for office again. In fact, as early as mid-1954 he was considering ending his presidency after one term. In a letter to his brother Milton, the president wrote, "if ever . . . I should show any signs of yielding . . . please call in the psychiatrist—or even better the sheriff."[14]

Several prominent Republicans were suggesting that Eisenhower should be drafted to run in 1956, but Bill Knowland was not one of them. He told a panel of newspapermen that he had never believed in the doctrine of the indispensable man and that the party should not have a reluctant candidate. When pressured about whether he would

be a candidate, Knowland said that he would decide only after Eisenhower declared he would not run. But Knowland disagreed with the conventional wisdom that Eisenhower was the only Republican candidate who could win in 1956. "I think the Republican nominee at the next convention will be elected," he said.[15]

Nevertheless, a poll taken on February 13, 1955, pitting Richard Nixon against Adlai Stevenson showed Stevenson favored by 61 percent to Nixon's 39 percent. An April poll had Earl Warren in a dead heat with Stevenson. On May 13 Knowland polled 40 percent of the vote against Stevenson's 60 percent. Even against Senator Estes Kefauver, Nixon was favored by only 41 percent of those polled; Kefauver, by 58 percent. The polls were a bad sign for any Republican other than Eisenhower. Nixon himself indicated that Ike was the only Republican who could win.

Pundits were suggesting that Earl Warren would seek the presidency one more time if Eisenhower were to back out. So persistent was the talk that Warren was forced to issue a statement expressing his embarrassment and trying to put an end to it. In mid-June, New York Times writer James Reston was speculating that Knowland had his eye on the vice presidential nomination. That, of course, would mean ousting Richard Nixon. Eisenhower, by selecting Knowland as his running mate, would remove him from his seat in the Senate to a job that a former vice president, John Nance Garner, had described as not worth a spittoon of warm spit.

Reston reported that Knowland and Goodwin Knight were forming a California coalition to take Nixon out of play at the Republican National Convention; the plan was to send Knight to the convention holding California's 70 delegates. "Mr. Knowland's supporters hope that Mr. Knight will not agree to cast the state's delegation for Mr. Nixon in the vice presidential balloting. They also hope they will be able to persuade the president that he should not insist on Mr. Nixon as his running mate if Mr. Nixon cannot even get the support of his own state delegation."[16] But the Knight/Knowland coalition was never formed, and the Sacramento Bee 's Washington correspondent, Gladstone Williams, discounted that scenario: according to him, Knowland really was looking to the presidency if Eisenhower decided against running.[17]

On September 24, Eisenhower suffered a heart attack—a coronary thrombosis that totally incapacitated him for several days and kept him hospitalized for almost two months. Nixon's name, of course, came up as a candidate to replace the sixty-four-year-old Eisenhower, but Knowland scoffed at the idea. "I do not consider a Pepsodent smile, a ready

quip and an actor's perfection with lines, nor an ability to avoid issues, as qualifications for high office."[18] It was one of the few times that Knowland spoke publicly in a derogatory manner about Nixon.

Governor Knight's animosity toward Nixon can be traced back to 1950, when Nixon put up a candidate to oppose Knight's bid for reelection as lieutenant governor. After winning that race, he moved up to governor when Warren was appointed chief justice. Their relationship continued to sour, and on October 5, 1955, Knight said that if Eisenhower chose not to run again he would head up the California delegation to the Republican National Convention as a favorite-son candidate, even if it meant confronting Nixon directly. "The Republicans of California will want to be represented by a completely independent delegation devoted to the Republican Party and not to the ambitions of any one man," he declared.[19] The California governor said he would go ahead with his favorite-son slate regardless of what Nixon did, stressing that he was for Eisenhower "first and foremost" and that he would head the delegation to support the president if he chose to run again. Few sophisticated followers of politics in California were fooled. Favorite-son candidates almost always have their hearts set on the White House, hoping that somehow their long-shot run will succeed.

Knowland disputed Knight's position, saying that the Republican voters in California would determine whom the delegates would support. Representative Carl Hinshaw, chairman of the state's Republican delegation in the House of Representatives and a Nixon supporter, also jumped on Knight, who, he said, was seeking to position himself as a presidential candidate: "Except in the ambitious dreams of Mr. Knight, he is something of a joke in national politics and it will prove most unfortunate for the Republican Party of California and in the nation if this unseemly and almost indecent haste to exploit the unfortunate illness of President Eisenhower should result in creating a false impression of his real standing."

Knight responded sharply to the criticism. "Although I have been endorsed and supported by organized labor, still both in public and private utterances, I have made it clear I have the word 'Republican' blazoned across my chest. I have done nothing inimical to the Republican Party or the Republican platform. From 1932 to 1952 we were affected with creeping paralysis and couldn't talk to anyone but fellow Republicans. Let's not lose the contact we now enjoy."[20] But not long after, Knight said he doubted whether either Nixon or Knowland could be elected president.

While Nixon and Knight were sparring, Knowland was keeping out

of the fight, even though he was thought to have joined Knight's camp in a stop Nixon" effort. Knowland was urging that presidential aspirants proceed cautiously until it was determined whether Eisenhower was going to run again. Although Nixon was organizing his troops, Knowland was sitting quietly in the background in California. After all, there was plenty of time; the primary in California wasn't until June.

William L. Roper wrote for Frontier magazine that California could "become the battleground of one of the bitterest pre-primary fights in the history of the Grand Old Party. Even if does not commit suicide, it will never be the same."[21] (During the 1958 gubernatorial campaign, Roper would become Knowland's publicity director in Southern California.) After New York, California would have the largest bloc of delegates at the Republican convention and Knight, Knowland, and Nixon each wanted that bloc. There were proposals for a coalition delegation with votes split among Nixon, Knowland, and Knight. Knight dismissed them, saying that "bloc delegations are stupid, dangerous and inevitably disastrous."[22] But when Eisenhower decided to run again that's just what happened, with California's three most important political leaders sharing the delegation.

Knowland later recalled that there were serious doubts whether Eisenhower could or should run for president again because of his heart attack. Immediately the name of Eisenhower's brother Milton came up as a possible candidate to replace him. Knowland rejected the idea, saying there should be no "heir apparent" and that the president should do nothing to influence the choice of his successor; Knowland knew, of course, that Eisenhower would never choose him. "I don't think I need to point out . . . that this was greeted with something less than enthusiasm by not only what might be termed the Taft wing of the party, but by most of the people who had supported Eisenhower," Knowland said. "Had this happened, I think there would have been a major confrontation in the Republican Party, because they were not prepared to accept Milton Eisenhower in place of Dwight Eisenhower."[23] Members of Congress, cabinet officers, and other friends wanted to know before the 1956 primaries whether Milton was going to be substituted for the president. They didn't want the president coming into the Republican National Convention in August making known at the last minute his desire for his brother to succeed him.[24]

Eisenhower also was considering Tom Dewey as a possible replacement. "You know, boys," Eisenhower told Sherman Adams, Jim Hagerty, and others, "Tom Dewey has matured over the last few years and he might not be a bad presidential candidate. He certainly has the

ability and if I'm not going to be in the picture, he represents my way of thinking." Hagerty and Adams were shocked. Hagerty said the president was asking for a revolt of the right wing of the party if Dewey were put forward again. They might even nominate Knowland, Adams protested. "I guess you're right," Eisenhower said and dropped the idea.[25]

It didn't matter, because Knowland had his own plans. He would be a "provisional" candidate for president. He would not run against Eisenhower, but if the president wasn't going to seek a second term, Knowland wanted to know as soon as possible so he could put his campaign into gear. He made it known that he would be "available" in case Eisenhower bowed out. Knowland already was planning to enter the California campaign in hopes of landing its 70 delegates, regardless of what Nixon or Knight might do. Knight still wanted to go to the convention as a favorite-son candidate, a position that would give him political leverage at the convention. In a three-way race, according to the political prognosticators, Nixon would win, but if Knight were to throw his weight to Knowland then Knowland would carry the delegation. No one saw Knight as having a chance of winning.

Toward the end of the year, Knowland had given four major speeches, in Boston, New York, Cleveland, and Peoria, Illinois. And he had scheduled at least thirty speeches outside of Washington in the months ahead. The Sacramento Bee editorialized, "It would be unreasonable to suppose he would be laying the foundation he is without some conviction [that Eisenhower wouldn't run again]. He may be tight."[26]

On December 12, Hagerty asked Eisenhower if he was planning on running again in 1956. "Jim," Ike told his press secretary, you've always known that I didn't particularly want to be President, and that I had always thought that while I was in the White House the Republicans would have an opportunity to build up men who could take my place and who could successfully keep out of that office the crackpot Democrats who were seeking it. I don't want to run again, but I am not so sure I will not do it. We have developed no one on our side within our political ranks who can be elected or run this country. I am talking about the strictly political men like Knowland. He would be impossible and so in answer to your question, I don't want to but I may have to. "[27]

Eisenhower was worried that Knowland couldn't beat men like Adlai Stevenson, Estes Kefauver, and Averill Harriman. "I can't see Knowland from nothing. . . . Actually I can't see anyone in the Senate who impresses me at all on both sides of the aisle."[28] The president's dismis-

sive statement reveals his remarkable distance from the upper house, which would in fact produce every presidential nominee for both parties for the next four elections.

The men closest to Eisenhower didn't like Knowland much either. They devised a scheme that Knowland resentfully called "a squeeze play." The plan was to get Eisenhower to withhold any announcement of his intentions until late March to keep Knowland and any other presidential hopeful from entering the early Republican primaries. Then if Eisenhower decided against running, the plan went, he could announce his chosen successor just before the convention opened. Knowland had other plans. He gave Eisenhower an ultimatum: if the president didn't announce by January 31, he was going to enter the primaries anyway. But one Eisenhower aide remarked, "Knowland can't alter our plans. He's the only man trying to force an early announcement, and one person can't make much of a stir. If you think about it a moment, you realize that it's almost miraculous that no one else in the party is insisting on an early announcement. No matter what he does, there will be no change in our present plans."[29]

On another front, an anonymous group was circulating posters seeking support for Knowland if Eisenhower decided against another term. Copies of the posters can be found among Nixon's papers in the National Archives, indicating the extent of his interest in his rivals. The poster was explicit that the efforts on Knowland's behalf were only to be made in the event Eisenhower decided against running again, and it was printed by the "Knowland for President . . . If . . . Committee." It listed no names—only a Glendale, California, address for anyone interested in receiving more copies of the poster: "Please do not attach any special importance to the personnel of this committee, or to the headquarters. We are busy people who will have no time for interviews. That is why we are using only a post office box." But the writers claimed, "If we do not take such steps, it is very possible that the next President of the United States will be named in a smoke-filled room occupied by an amazingly small number of people operating under the direction of political strategists whose choice for President would be very unsatisfactory to the Knowland-Taft-MacArthur elements."

Those who devised the poster said that Knowland knew nothing of the group's efforts. "If we had gone to him first, he would very likely have opposed it on the grounds that it might embarrass his position in the party. We believe that the situation is so fraught with danger in the light of the world crisis that a 'Draft Knowland' Movement should rise above even its own personal desires, to the end that the Republican Party

be saved from the menace of appeasement, New Dealism, U.N. tyranny and a score of other threatening potentials that might mature if a last-minute decision had to be made by a handful of men who literally hate such statesmen as Knowland, Bricker, MacArthur, McCarthy, Jenner, Welker and their compatriots."[30]

Knowland was endearing himself to the growing conservative movement across the United States. The archconservative William Buckley Jr. began to publish a new magazine, the National Review , and Knowland wrote an article for its first issue on November 14, 1955. He warned against Soviet disarmament proposals and called for the Republicans to return to the 1952 platform pledge to seek the freedom of people enslaved by Communist dictators. Another article in the issue reported that "right wing organizations are trying to interest conservatives in the possibility of a coalition campaign for the presidency to start that fall. Senator Knowland, according to the plan, would act as the titular standard bearer on the understanding that the coalition's final selection will not be made until the convention. Knowland's immediate task will be to capture the all-important California primary, to enter the Oregon primary, and perhaps, Minnesota's."

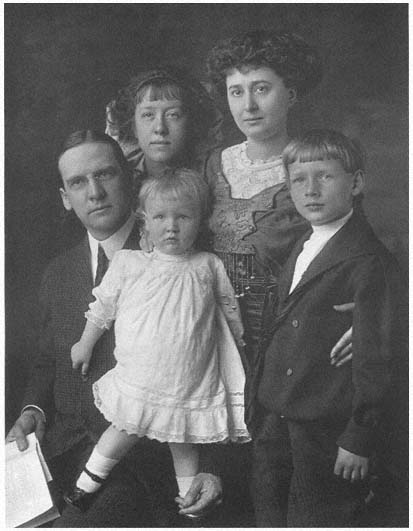

The Knowlands: young Bill (center)

with, from left, JR. (father),

Eleanor (sister), Emelyn (stepmother),

and Russ (brother)

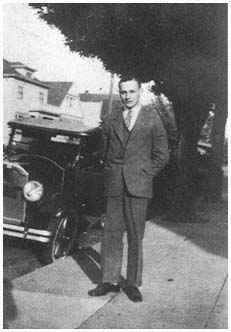

William F. Knowland in 1926

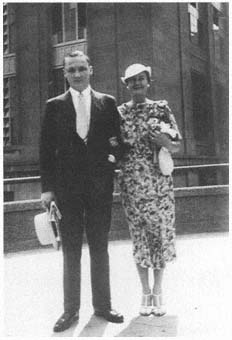

William F. and Helen Knowland on a visit

to Washington, D.C., in 1936

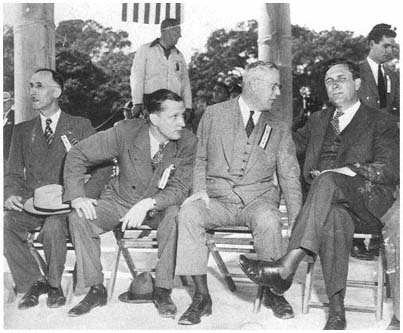

From left: Congressman Ralph Elste, William F. Knowland,

Earl Warren, and Wendell Willkie in Oakland in 1940

Major William F. Knowland in Paris in 1945

The Knowlands during the Senate years: William F. (center)

with, from left, Joseph (son), Emelyn (daughter), Helen (wife),

and Estelle (daughter)

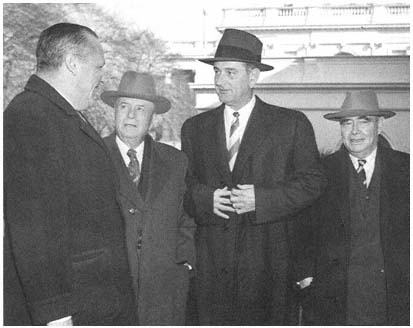

From left: Senate Minority Leader William F. Knowland,

House Speaker Sam Rayburn, Senate Majority Leader

Lyndon B. Johnson, and House Minority Leader Joe Martin in 1957

President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Senator

William F. Knowland (Courtesy United Press International)

Helen and William F. Knowland reading early results in

1958 gubernatorial race (Photo: Lonnie Wilson)

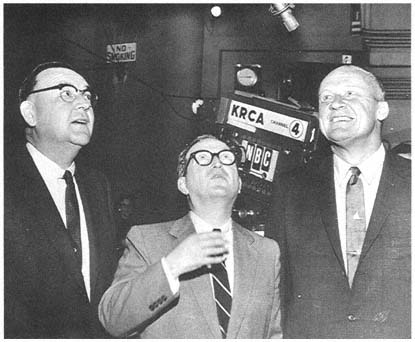

Gubernatorial contenders Pat Brown (left) and William F. Knowland (right)

watch Lawrence Spivak toss a corn to decide who will be interviewed

first on 1958 TV program (Courtesy Los Angeles Times )

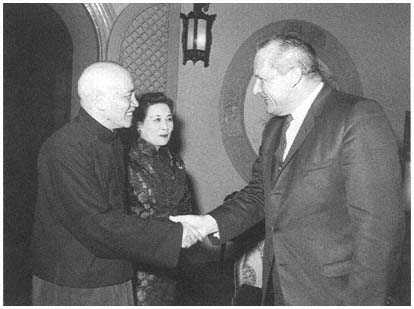

From left: Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang with

William F. Knowland in Formosa in 1963 (Photo: Wu Chung Yee)

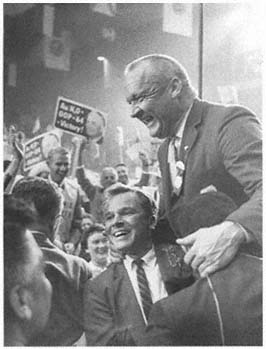

William F. Knowland amid California delegates at 1964 Republican

National Convention in San Francisco (Photo: Lonnie Wilson)

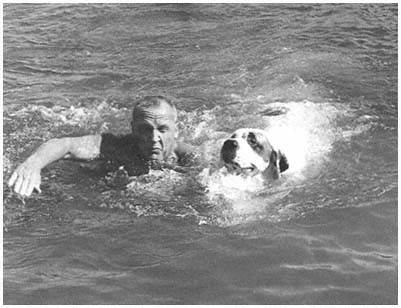

William F. Knowland at play with one of his two St. Bernards

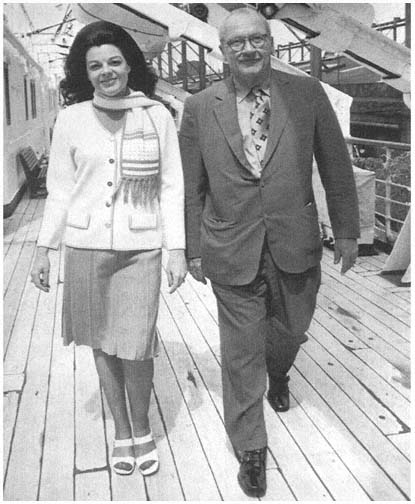

William F. and Ann Knowland on their honeymoon

in 1972 (Courtesy Associated Press)