PART THREE—

OF THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANIARDS, INTRODUCTION OF THE CHRISTIAN FAITH, AND OF THE MISSIONS

Chapter One—

Futile Expeditions of the Spaniards to California.

Father Salvatierra Gains a Firm Footing and Establishes Mission Loreto

The only purpose of Divine Providence in the discovery of the route to the East Indies around the Cape of Good Hope and in the finding of the fourth continent seems beyond a doubt to have been the expansion of the Christian Faith and the eternal salvation of the many heathen who live in the East and the West. Aside from this, as Saint Theresa has said, these discoveries have brought to Europe and Europeans more harm than good. Many white men go to eternal perdition in India who could have found salvation in Europe. Men could have lived very well, just as in former times, without the goods, without the gold and silver which are brought from the New World and which only serve to increase pomp and voluptuousness. These things, however, were the little decoy whistles, or the bait, which lured foreign nations into the New World, and their explorers certainly did not spare any effort—particularly in America—to find treasure. There was no ocean they did not cross, no river they did not ford, no corner they did not search in the first century of their occupation.

As a consequence of this untiring zeal to search for and to discover new treasures in these new lands, poor California could not very long remain hidden. The conqueror of the land and city of Mexico, Hernán Cortés himself, wanted also to become the conqueror of California. In the 'twenties of the sixteenth century he had sent several people to California, but all of them had poor success. Cortés' luck was better than that of the previous explorers; he at least saved his skin and got away to Acapulco! After Cortés, more than ten other Spaniards attempted to conquer California for the Crown of Spain, partly at the king's expense, partly at their own; but until the end of the century all their efforts and expenses were in vain. Their enterprises remained fruitless more because of the barrenness and aridity of the soil, as

described in Part One of these reports, than because of the resistance of the inhabitants which the Spaniards encountered. Although there were bloody heads at times, because the California Indians felt bitter toward the whole Spanish nation, thanks to the evil behavior and infamous practices of the many pearl fishers who had enraged the natives.

The Spaniards thought they would find rich gold and silver veins in California, as well as rich and productive soil. Since they found neither and were forced to live off the provisions they had brought along on their ships, all of them soon lost courage and turned back. It went so far that the Royal Council in Mexico proclaimed California an unconquerable land, and with this decision, California was forgotten. During the reign of Charles II, a certain Francisco Luzenilla[26] wanted to risk one more expedition to California—at his own expense and without assistance from the royal treasury—but his request was rejected.

A member of the Spanish expeditions to California undertaken in the 1680's was Father Eusebius Kino,[27] then a Jesuit missionary in Sonora and formerly professor of mathematics at Ingolstadt. It did not seem impossible to him, or even very difficult, to conquer this land, provided the sole purpose was the eternal salvation of the natives, and if one brought with him a good supply of patience, generosity, and fortitude.

One of Father Kino's contemporaries was Father Juan María Salvatierra, a Jesuit from Milan, of noble ancestry, formerly missionary in Tarahumára, Superior of all the missions, and later Provincial of the New Spain or Mexican Jesuit province. He was known to be a man of great religious zeal, gentle disposition, humility, patience, and kindness. At the same time he also possessed a healthy, strong, and powerful constitution. He gave many proofs of his qualities, as can be read in the history of his life, which has appeared in print. Father Kino discussed California at length with Father Salvatierra when the latter visited the missions of Sonora in his official capacity. Both men longed to go there; both felt a great desire to start the missionary work and the conversion of the Indians in California; however, God reserved this honor for Father Salvatierra alone. He finally received permission to sail to California after overcoming many objections from his superiors, as well as from the High Council and the Viceroy of Mexico, and after many presentations, much pleading, and loss of time. The Viceroy, however, stated that the undertaking must be carried out at the expense of Father

Salvatierra, that the Father could not hope for help from the royal treasury, and would have no right to demand such help. Father Salvatierra had nothing except a few good friends, his gentle disposition, and his faith in God. And God did not forsake him, but provided him with a number of benefactors who desired to participate in such a holy work. Among others, a secular priest from Querétaro, Juan Cavallero y Ozio, donated no less than twenty thousand pesos; that is, forty thousand Rhenish guilders. He added to this gift his pledge to honor and pay promptly all notes drawn by Salvatierra on Juan Cavallero's name. A rich gentleman from Acapulco, Gil de la Sierpe, lent him a small galleot, gave him some alms, and made him a present of another vessel.

Thereupon Salvatierra enlisted five soldiers, hired several others who could be of use, and loaded the ship with a small cannon and enough corn, dried beef, and other necessities to supply the group, as well as the California Indians, for several months. In October, 1697, Father Salvatierra ordered the anchors to be lifted and set sail from the province of Sinaloa under Divine guidance and the mighty protection of Our Lady of Loreto. Happily he landed nine days later, on a Saturday, in the Bay of San Dionisio, which is now named after Our Lady of Loreto.

The California natives soon noticed the difference between these foreigners and new guests and those others whom they had seen previously in their land from time to time. After a few days, they laid aside their mistrust and sought to make friends with the newcomers. Father Salvatierra increased this friendship day by day with the help of small gifts and his own kind and gentle manner. Yet at times minor frictions did occur, but were settled without bloodshed. It was impossible to let the Indians have their will in all things, or to satisfy completely their voracity, because they sought to acquire by force what was not given to them voluntarily.

A tent was set up to serve as a chapel, several huts were built of the poor California lumber, and all was enclosed by a parapet and a low bulwark. Everything which was necessary or customary under such circumstances was done as well as possible as a safeguard against unexpected or sudden attack from the barbarians.

No time could be lost. There were too many mouths to feed, few provisions available, and absolutely nothing could be drawn from the land. For these reasons it was considered wise, after a few weeks had

passed, to send one of the two ships back to Sinaloa in order to fetch more provisions for California. In the meantime, Salvatierra began to learn the native language and to instruct his new parishioners. For this purpose he taught Spanish to a few young Californians. Thus he laid the foundations for the first mission, which he wished to be called Loreto in honor of the Mother of God.

After a few months, the little ship which was sent to fetch provisions returned well loaded, just as want was beginning to make itself felt. It also brought some new soldiers and Father Píccolo, a Jesuit from Sicily. Before a year had passed, Father Salvatierra had learned the essentials of the native language, and he undertook a trip into the surrounding territories to visit neighboring tribes. Father Píccolo, however, laid the foundations for a second mission, eight hours from Loreto, in the year 1699. He named it for the Apostle of the Indies, St. Francis Xavier.

Chapter Two—

Of the Progress of the Established Missions and of the Founding of New Ones

The year was 1700. Heretofore the enterprises of Father Salvatierra had brought no expense to the Catholic King. With the growth of the new mission, however, and with the preparations to penetrate farther into the land to found additional missions, expenses increased considerably. Salvatierra submitted a complete account and report to the Viceroy of Mexico, informing him of all that had occurred up to that time. He put before the Royal Council in Guadalajara an account not only of past expenditures, but stressed particularly the poverty of the mission. He mentioned the shipwreck of one of the vessels, the poor condition of the other, and emphasized the necessity of putting the

soldiers' pay on a stable basis. He pointed out that the casual alms which he received might cease any day, and might suddenly force him to abandon the enterprise. The Royal Council referred Father Salvatierra's case to the Viceroy. The latter reminded Salvatierra that he had been granted permission to go to California only if he could cover his own expenses. The Viceroy, however, did not consider the fact that taking possession of land is one thing, while holding it for the future is another. Salvatierra had already accomplished the first. The latter, however, he could not promise to do. After many remonstrances and a lengthy correspondence, the whole case was submitted for the king's judgment. Owing to His Majesty's sickness and subsequent death, however, as little was achieved and gained in Madrid as in Mexico.

To these complications must be added the false rumors and the jealousy of those Spaniards who did not believe that the Jesuits should have ventured to penetrate into the California world of rocks, thorns, and barbarians, to live there solely and exclusively for the glory of God and the salvation of California Indians. Many Spaniards had sailed to California before the Jesuits; yet they could not and would not remain there. These rumors had already caused a decline in the generosity of some donors. Furthermore, in reports sent to Mexico, the captain of the soldiers then in California violently slandered the padres, sarcastically referring to their enterprise as an impossibility, as an insane whim. He did this because he was not permitted to employ the natives for pearl fishing as he wished. According to a royal decree, he owed obedience to Father Salvatierra, and the latter forbade him to use the Indians for such purposes. Besides, the great amount of work and hardship, of which there was no lack in such a country and at the beginning of such an enterprise, had already tired and irritated him.

In view of so many negative answers and delays, and in view of the dangers and difficulties in securing quickly and safely the necessary provisions from across the sea, Salvatierra conceived the idea of opening a land route to California. At that time it was still uncertain whether California was a real island or only a peninsula. Missions had been established along the coast, on the Mexican side of the Gulf of California, from the twenty-fifth to the thirty-first degree. Salvatierra believed, if California were not an island, that it would not be difficult to establish communication by land between these missions and others to be founded

in California in the future. This would be an advantage to the new missions. He did not know, nor could he imagine at that time, that seventy and more years would pass before the missions on either side of the gulf would meet at the Río Colorado. He begged his old and good friend Father Kino to undertake a trip from Sonora to the abovementioned river to determine whether California was part of the mainland of North America, or was cut off by an arm of the sea and therefore an island. The journey was made not once but several times, although not along the seashore because of lack of water and the sandy coast, which is rather wide and almost thirty hours in length. By long, though necessary detours, the Río Gila was reached, and finally the Río Colorado. The expedition sailed down the river for several miles, crossed it, and marched many miles inland on the other shore. For the first time, although not with absolute certainty, California was declared a peninsula, much to the pleasure of Father Salvatierra. Nevertheless, much was lacking and still is to this day to bring about communication by land and to make possible the transport of provisions from the Pimería to California, as conceived by Father Salvatierra. Although by now the missions in California extend to the thirty-first degree, there still lies a considerable stretch of apparently bad land across from the point where California meets the Pimería. In the Pimería, Caborca is still the last mission to the north, just as it has been for more than seventy years. The many revolts and incursions, not only by the Pima and Seri Indians, but above all by the cruel Apaches, have kept these territories in constant fear for the last sixty years. These savages have plundered the land, destroyed the missions, and with their lances and arrows sent many a Spaniard to his grave.

Meanwhile, not only had the two original missions of Loreto and San Xavier become more and more firmly established, but one by one eighteen others had been erected. The entire work was accomplished by missionaries themselves, although their efforts, worries, and troubles were more than once about to be abandoned and destroyed, since hundreds of dangers had to be faced, hunger, numerous shipwrecks, and native wars and uprisings.

Philip V, of glorious memory, contributed not a little to this growth, for hardly had he ascended the throne than he ordered his regent in Mexico to pay annually to all the missionaries of California as much as to all the other missionaries, that is, six hundred Rhenish guilders for

their support. Furthermore, the California churches were to be equipped with bells, appointments for the celebration of Mass, and other necessities. In addition, a company of twenty-five soldiers was established, and a ship with a pilot and eight sailors was provided to serve the missions. For the permanent support of the entire undertaking, the treasury of Guadalajara was instructed to pay thirteen thousand pesos, or twenty-six thousand florins, annually. These were the royal orders. Many years passed, however, before they were carried out. Since no news from Mexico was received in Madrid announcing the execution of these decrees, they were reissued in 1705, 1708, and 1716, and, finally, in 1716 actual payments were made for the first time.

Before that time, that is, from 1697 to 1716, more than three hundred thousand Spanish pesos duros , which is more than six hundred thousand guilders, had been spent on poor California. This sum, not so impressive in the New as in the Old World, yet not small or insignificant anywhere, had been collected by Father Salvatierra and his padres, and magnanimously donated by private persons eager to help in the work of saving souls. This may illustrate the generosity of rich Spaniards born or residing in America in instances where God's honor was concerned. These benefactors of the California missions were not left without just reward. For instance, money almost seemed to rain into the house of His Excellency, the high and well-born Marqués de la Villa-Puente, whose money chests were at all times at the disposal of the California and China missions, as well as other spiritual and worldly charitable organizations. He could equip and deliver several regiments of soldiers to his king during the protracted War of the Spanish Succession. When his good friend Don Gil de la Sierpe died in Mexico, Father Salvatierra envisioned his entrance into heaven, guided by fifty innocent and beautifully clothed children, at the exact hour of his death. The Father told those who were about him of this vision, and soon thereafter news from Mexico arrived verifying and ascertaining the truth of his statements as to the day, hour, and passing of Don Gil. All of these fifty children were baptized California Indians, and just that many and not more had died up to that time. Would similar rewards be lacking elsewhere if examples such as Don Gil's were followed? There is no virtue, according to Holy Scripture, which promises more rewards than charity. Yet even without any advantages it would be recompense enough for a

Christian heart to have done good, to have helped the soul or body of a person in need, and thus to have offered a helping hand to Jesus our Lord Himself.

Meanwhile, in 1704, the first church was consecrated to Our Most Blessed Mother of Loreto. Shortly thereafter the sacrament of baptism was administered to a large number of adult California natives for the first time. It was considered prudent, yes, necessary, to test the perseverance of the newly converted for six years.

About this time, Father Salvatierra had to leave California for a time. In spite of his refusals, he had been forced to take upon himself the office of Provincial in the Mexican province. His absence, however, was not of long duration. Even during the first year of holding his new office, he crossed the sea, spent two months in California, and worked like any other misssionary. In 1706, he received permission from Rome to resign his post, and returned to California in the following year, firmly resolved to spend the rest of his days among the natives. In 1717, however, he had to obey the orders of His Excellency, the Viceroy of Mexico, who called him to that city in order to confer with him about California. Father Salvatierra undertook this trip in spite of his advanced age and feeble health. He did not get farther than Guadalajara, the residence of the bishop, about a hundred and fifty hours distant from Mexico. He fell ill, and in the college, amid his brethren, Father Salvatierra died. It is to be believed that he soon reached the shores of eternal bliss after having crossed the California Sea more than twenty times and having exposed his life to many dangers by helping others solely for the love of God and his fellow men. The glory he acquired through his heroic virtues and his pains and labor for the salvation of the natives is everlasting. For this reason the whole city mourned, and he was interred there in the Lauretan chapel with all signal honors rendered to him by the cathedral chapter as well as by the Royal Council.

I have already reported that, all in all, eighteen missions had been established in California. Of these, some were later transferred to other places and given different names. Two were combined into one, so that at the beginning of 1768 fifteen missions were counted. I want to enumerate them, not in chronological order, but according to their geographic location from the south to the north.

The first is called San José del Cabo because it is situated very close

to the cabo or promontory of San Lucas on the California Sea. It was founded in 1720. The next, Santiago, or St. James, is twelve hours distant from the first named and four hours from the California Sea. It was established in 1721. The third, Todos Santos (All Saints), is situated across the peninsula from the aforementioned mission, almost on the shores of the Pacific Ocean. It was established in 1720. A missionary could make the trip between the two missions in one day were it not for an almost insurmountable mountain range, the furthermost point of which is called San Lucas, running between the two. A detour of three days is necessary should one of the two missionaries wish to visit the other. The one living at Santiago also administered Mission San José del Cabo. The fourth is called Nuestra Señora Dolorosa (Our Lady of Sorrow). It is about seventy or more hours distant from Todos Santos and six hours from the California Sea, and was founded in 1721. The fifth, San Luis Gonzaga, is situated between the two seas, seven hours from Mission Dolores, and was established in 1731. The sixth, San Xavier, is thirty hours distant from the aforementioned mission and eight hours from the California Sea. It was founded in 1699. The seventh, Loreto, was started in 1697. It is eight hours northeast of San Xavier, within a stone's throw of the California Sea. The eighth, San José Comondú, is situated closer to the Pacific than to the California Sea, a day's journey from San Xavier toward the northeast. It was established in 1708. The ninth, Purísima Concepción (Immaculate Conception), is a hard day's journey from San José del Cabo, going northwest, and not far from the Pacific. It was established about 1715. The tenth, Santa Rosalía, lies half an hour from the California Sea, a long day's journey from Purísima Concepción in a northeasterly direction, and was founded in 1705. The eleventh, Guadalupe, and the twelfth, San Ignacio, were founded in 1720 and 1728, respectively. Mission Guadalupe is a two-day journey from Purísima Concepción toward the north, not far from the Pacific Ocean, and San Ignacio is situated almost in the middle of the country, a one-day trip from Guadalupe and Purísima Concepción. The thirteenth, Santa Gertrudis, a two-day journey northwest of San Ignacio, was established in 1751. The fourteenth, San Borja, is a hard two-day journey from Santa Gertrudis in a northeasterly direction. It was founded in 1762. The fifteenth and last, Nuestra Señora de Columna (Our Blessed Lady of Columna), is a three-day journey from San Borja toward the California

Sea, and below the thirty-first degree, north. It was established in 1766.

Each one of these fifteen missions had in my time its own priest, except the first two, which were both administered by the same missionary. All of them are built along an arroyo or rain-water course. Nearly all of them stand between high, forbidding, almost barren rocks which are difficult to climb. They are situated in places, which, after much searching and counseling, were considered the most favorable. A permanent store of drinking water was of foremost importance in choosing each location.

Of these fifteen missions, six were endowed by the Marqués de la Villa-Puente; two by the Duquesa de Béjar and Gandia, of the house of Borgia; two by the secular priest Don Juan Cavallero y Ozio; one by Don Arteága; one (from his inheritance) by Father Luyando, a Jesuit from Mexico and a missionary in California; one by the Marquesa de la Peña; another by the Marqués Luis de Velasco; and finally, one by a certain congregation in Mexico. Out of gratitude and to their eternal glory, these honored founders and benefactors are mentioned here.

Many hardships were checked by the payments received from King Philip V and by the aforementioned endowments to the missions (to which all the California natives belonged who lived between Cabo San Lucas and the thirty-first degree, north). Although it required great effort, almost all the missions had found some land for sowing and planting and for breeding large and small animals, horses and mules. Thus help could be given not only to the sick and needy Indians, but also to soldiers and sailors. Notwithstanding these efforts, many thousands of bushels of Indian corn, dried vegetables, many horses and mules, fats, and sometimes also meat had to be brought from places across the sea. The supplies were at times so meager in California that a soldier received only half his grain ration, or had to eat his meat without bread, as one missionary had to do for six weeks.

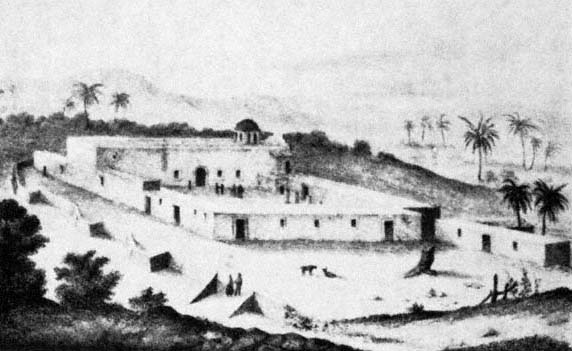

After enumerating the missions, their location, and their benefactors, it might be agreeable to the reader if he were introduced to the foremost of these missions, the one of Loreto, the capital city, and at that time the residence of the California Governor and Viceroy. From this description, the reader may draw his own conclusions about what to think of the rest of those California cities and places to be found on maps, in histories, and other books, but which are not actually in California. Loreto is, as I have already remarked, situated only a stone's throw from

the California Sea. It lies in the center of a stretch of sand which reaches for almost half an hour's distance up to the mountains. This land is without grass, without a tree, a bush, or any shade. Loreto bears as little resemblance to a city, a fortified place, or a fortress, as a whale to a night owl. The dwelling of the missionary, who was also the administrator and who had a lay brother to assist him, is a small, square, flat-roofed, one-story structure of adobe brick thinly coated with lime. One wing of the building is the church, and only this one is, in part, constructed of stone and mortar. The other three wings contain six small rooms each, approximately six yards wide and as many yards long, with a light hole toward the sand or the sea. The vestry and the kitchen are found here, also a small general store, where the soldiers, sailors, their wives and children buy buckles, belts, ribbons, combs, tobacco, sugar, linen, shoes, stockings, hats, and similar things, for no Italian or any other trader ever thought of making a fortune in California.

Next to this quadrangle are four other walls, within which dried steer and beef meat, tallow, fat, soap, unrefined sugar, chocolate, cloth, leather, wheat, Indian corn, several millions of small black bugs which thrive on the grain, lumber, and other things are stored.

Beyond these imposing buildings, a gunshot's distance away, a shed may be seen which serves simultaneously as guardhouse and barracks for unmarried soldiers. The entire soldiery and garrison of Loreto, their captain and his lieutenant included, consists occasionally of six or eight, but never more than twelve or fourteen men.

In addition, there are toward the west two rows of huts made of dirt, in which dwell about a hundred and twenty natives, young and old, men and women. About two to three and a half dozen mud huts are scattered over the sand, without order, looking more like cowsheds of the poorest little village than homes, and usually containing but one single room. These are occupied by the married soldiers, the few sailors, the one and a half carpenters and equally numerous blacksmiths, and their wives and children, and serve as lodging, living room, storeroom, and bedroom. Finally, a few poles thatched with brush make up the armory, or the shipyard. All this is Loreto, the capital city of California! He who has seen the Moscovite realm, Poland, or Lapland will know whether there is any small village in these countries or whether there is a milking shed in Switzerland more dilapidated than Loreto and its huts. Moreover,

the heat in summer is incredibly intense, and there is no other relief from it save a bath in the sea. There is neither running nor standing water on the surface, although it can be found by digging down into the sand to a certain depth. On the other hand, there is no scarcity of mosquitoes!

May God be gracious to the honorable gentleman Don Gaspar Portolá, a Catalonian, captain of dragoons, and first Governor of California from 1767. The office was conferred upon him as an honor and a reward, because of false reports about the good quality and wealth of the land. His punishment, however, could not have been more severe (except death, the gallows, or prison for life) had he sworn a false oath to the king or proved a traitor to his country. Of all the physical and mental pleasures which people of his character usually seek, none is to be found in California. He is practically forced to remain within his four little walls, day in and day out, throughout the year. Where could he go? With what and with whom could he entertain and enjoy himself or pass the time? In the environment of Loreto and in all of California, there is no hunting, except for the natives, no place to walk, no games to be played; there are no conversations possible, and no visits paid. In a word, there is nothing, literally nothing, for such a man to do. The amount of business, or the dispatching of couriers will not shorten the time for him. All that a viceroy of California can do in the course of a year is to mediate a few minor quarrels and brawls between the hungry miners, or to mete out punishment if necessary. There may be a few letters for the secretary, whom he brought along, to write ordering some Indian corn from overseas for his dragoons and miquelets.[28]

There is, however, one advantage he can draw from this governorship if he were money mad or wished to save. He receives a yearly salary of six thousand Rhenish guilders. Since there is absolutely no opportunity in California to be extravagant or to squander money, he can probably lay aside five thousand nine hundred guilders every year without being accused of penny-pinching or miserliness. His field chaplain, Don Fernandez, a secular priest, wanted to leave the country as soon as he saw that there was no one to speak to all day long and nothing to do but to sit in his hermitage, to gaze at the blue sky and the green sea, or to play a piece on his guitar.

Chapter Three—

Of the Revenues and the Administration of the Missions

Some of the revenues, which provided the missionaries and many of the Indians with food and clothing and helped to maintain the churches, were certain (except for the dangers of the sea), others accidental. To the latter group belonged everything which soil and the animals produced in return for much effort and work. More will be told about these in chapters five and six. The first mentioned were one thousand Rhenish guilders designated for each mission by the respective founder and benefactor. This sum could be spent at the missionaries' discretion.

According to the will and command of Philip V, each missionary in California was supposed to receive six hundred guilders annually from the royal treasury; that is, he was to receive as much as any other missionary who worked in the vineyard of the Lord in the Spanish possessions in the Americas. Such a decree was, however, not acceptable for three reasons. In the first place, the income was not secure, since the royal officials, using all sorts of pretexts, would at times omit payments for several years in succession. Then, too, the income did not seem sufficient, considering the infertility of the land and the necessity of importing everything which this money could buy from Mexico, which is such a great distance away. And finally, there was no lack of generous people who offered a thousand guilders. Perhaps it was foreseen that California would bring very little to the royal treasury and that the expenses for ships and soldiers, already large enough, would be likely to increase in the future.

Consequently, from 1697 to 1768 all the missionaries in California were supported by private persons and not by the Catholic King. These benefactors donated either twenty thousand guilders in cash for every new mission or enough property to guarantee an income of about one thousand guilders per year. These properties and others bought with donated money and dedicated to the support of California missionaries specialized largely in raising livestock. These were scattered all over

Mexico, some of them as far as two hundred hours away from the capital city, Mexico, the home of the administrator, who had to take care of everything. His task was not easy, and his office caused him much travel and much sweat. Every year, in March, he had to send to each missionary the equivalent of a thousand guilders in goods. Each consignment depended upon the individual missionary's needs. These goods were moved overland by mules a distance of two hundred and fifty hours from Mexico to Matanchel on the California gulf. There they were loaded on ships and sent across the sea to Loreto, another three hundred hours' journey. On sea, everything was duty free; the sea transport itself did not cost the missionary anything, but the freight on land was more than one hundred guilders for only four bales of goods, even though the mules, after being relieved of their burdens, could graze freely, without any cost, on the pastures of America.

These bales contained all the precious things which a missionary in the course of a year needed for himself and for his church. They might include a coat, a few yards of linen, a few pairs of shoes, twenty or more pounds of white wax, some chocolate (which in America is like daily bread and which any common laborer thinks he is entitled to drink), and again, some linen or cotton goods with which other possible necessities, especially Indian corn for the natives in the event the harvest at the mission was insufficient, were to be bought in Loreto during the year. One year a surplice might be ordered, or some other priestly vestment; the next, a stole; the third, a choir cope, a bell, a carved or painted picture, an altar or something else for the church. The remainder, which usually made up about three quarters of the entire consignment, consisted of all kinds of blue and white, coarse and rough cloth to cover the naked Californians.

Of these naked ones who had to be clad, as many as could be fed and employed by the missionary were, so to speak, permanent residents at the mission. They worked at agriculture; they knitted and wove. Some were needed in the service of the mission as a sexton, goat herdsman, attendant for the sick, catechist, magistrate, fiscal, or cook (there were two and they were dirty, one for the missionary and one for the natives). Only four of all the missions, and small ones at that, were able to clothe and support all of their parishioners and therefore keep them in the mission throughout the year. In all the others, the natives were divided into

three or four groups, and each in turn had to come to the mission once a month. There they had to encamp for a whole week.

Every day at sunrise all the natives attended Mass. During the service they recited the Rosary. Before and after the service they were taught Christian doctrine by being asked questions in their own language. After this, the missionary gave them instruction, also in their native tongue, for a half or three quarters of an hour. Then, after having received breakfast, each one went either to work or, if he pleased, to wherever he wished; if the missionary was unable to provide him with food, he searched in the field for his daily bread. Toward sunset, at the call of ringing bells, they all assembled again to recite the Rosary and the Lauretan litany in the church or, on Sundays and holidays, to sing. Customarily the bells were rung three times a day, but they were also rung at three o'clock in the afternoon in remembrance of the mortal agony of our Lord and, according to Spanish custom, at eight o'clock in the evening to remind everyone to pray for the dead. After the week had passed, the natives returned to their native land, some three, others six, others fifteen and twenty hours from the mission. I mean by "native land" those districts in the open where each little tribe is accustomed to live, although each of them has at least a half dozen such districts. One of these territories gives its name to many tribes.

On the highest holidays of the year and during Passion Week, the whole congregation assembled. In addition to the usual fare, they received the meat of several head of cattle and a few bushels of Indian corn. Dried figs and grapes were generously distributed, provided these things were available. Similar foods or some pieces of clothing were also distributed as prizes in games or shooting contests.

To safeguard order in and outside of the mission, fiscals and magistrates were chosen from each group. Their duties were to bring those present at the mission into the church at a given signal and, at the proper time, to round up those who had been roaming the fields for three weeks and to lead them to the mission. Furthermore, they were supposed to prevent all disorders and public misconduct, to review the catechism in the morning before the natives left the mission and in the evening after they had returned, to persuade them to recite the Rosary in the fields, to punish culprits for minor offenses, to report serious crimes to the proper authority, to see that the natives preserved silence and

were reverent during religious services, to attend the sick in the field and bring them to the mission, and similar duties. As insignia of the office and the power vested in them, each carried a staff, sometimes one with a silver knob. Most of them were proud of their position, but only a few did justice to their functions, for quite frequently they received the beating and pushing around which they should have delivered to others. In addition to these officials, there were catechists who recited the Christian doctrine to the natives and instructed those who were especially ignorant.

To prevent disorder when there was not enough food for all the natives, the missionary or someone in his place distributed every day, after Mass and Christian instruction, cooked wheat and Indian corn among the blind, the aged, the weak, and the pregnant women. This was repeated at noon and in the evening after the Rosary. For those who were ill, special food was prepared, and the sick received meat at least once a day. When there was work to do, the laborers were offered three meals a day if they attended to their duty. The work was not hard. Would to God there had been enough of it to make all California natives labor and toil industriously all day as the poor peasants and craftsmen do in Germany. How many vices and misdeeds could have been prevented every day! The working hours began very late and ceased even before the sun had set. At noon the workers took a two-hour rest. Without doubt six common laborers in Germany achieve more in six days than twelve of these natives do in twelve days. Moreover, all their labor was exclusively for their own and their fellow men's advantage and benefit. The missionary gained nothing by it except worry and annoyance, and he could easily have procured somewhere else the twelve bushels of wheat or Indian corn he consumed during a year.

However, this missionary was the only refuge of young or old, the sick or the healthy. Upon him alone lay the responsibility for everything which had to be done. From him the natives solicited food and medicine, clothing and shoes, tobacco for smoking and snuffing, and tools if one of them wanted to do some work for himself. He alone had to mediate quarrels, look after small children who had lost their parents, care for the sick, and find someone to watch over a dying person. I knew of more than one missionary who could rarely begin his breviary by the light of the sun, such was his drudgery throughout the whole day. I could relate at length how, for instance, Father Ugarte[29] and Father Druet,[30] mud and water well over their knees, worked harder in the

stifling field than the poorest peasant and day laborer. Or, how others labored for their church and house, did tailoring and carpentering, or practiced the professions of masonry, cabinet-, harness-, brick-, and tile-making, or were physicians and surgeons, choirmasters and teachers, managers, guardians, hospital attendants, or beadles. The intelligent reader will easily understand all this when he recalls what was said in Parts One and Two of this book about the character of the land and its inhabitants. For the same reason, he will be able to conclude which were the revenues and incomes of the missionaries in California as well as in hundreds of other sections of the New World.

To the "revenues" the reader may also add the hearing of confession and the visiting of the sick out in the field and far away from the mission. At all times, day or night, the missionary might suddenly be called to a distant place, three, six, twelve, or twenty hours away, to administer the sacrament to a sick person. Sometimes he arrived too late despite his zeal and speed; at other times, however, the sick man himself walked part of the way to meet him. Or perhaps the missionary, after a long and exhausting march, would find the patient at the indicated place, but with nothing more serious than a slight swelling or the colic. Of one thing the missionary was certain. He would find no roof or bed on the whole journey but the sky and earth, and no food but what he carried with him. This caused difficulties and hardships for some missions, for often there was nothing to take along on such occasions. Under such conditions the missionary had to rely upon chocolate while traveling to and fro.

On one such occasion, I had to spend three consecutive nights in the open field. Because of a particularly bad stretch of way which I did not care to traverse in the dark, I had not been able to reach my house on the third day, as I expected. For my evening meal I had not even four ounces of bread (or more correctly speaking, corn pancakes) and not quite a cupful of water, and this was to be distributed among three people! The humorous part of the situation was that, shortly before opening my "cellar" and "bread basket," I had read in my breviary the following passage from Isaiah: "Dabit vobis Dominus panem arctum; et potum brevem." The patient in this case had nothing but two swollen cheeks. This happened in 1758. He was still alive and well in 1768.

To hear confession was in every respect a very disconsolate, highly annoying, and melancholic task (particularly after I came to know the

natives very well and learned to see behind their trickiness, hypocrisy, and their wicked way of life). This was not only because of the coercion or the fictitious devotion which was for many the only reason to go to confession, but also because of their stupidity and limited intelligence and the surprising ignorance they revealed in spite of repeated instruction. There were also the many temptations which they did not care very much to avoid, and the father confessor was unable to do anything about it. And finally, most annoying was the lack of preparation for confession and the continuous return to sin of all or most of them. I once asked a native woman who understood Spanish (it must have been during the pitahaya season) why she had not done the penance imposed on her after previous confession (and which may have consisted of reciting one or several rosaries). In good Spanish she replied, "De puro comer," "Because I was eating." I asked another woman, a rather intelligent person, what she had done or thought before my arrival at the church. The blunt answer was, "Nothing." She did not have to swear an oath; I believed it. My experience of many years with many such cases proved to me only too well that nothing is less important to the natives than to prepare for confession. One reason among others is that preparation for confession is an exertion engaging head, heart, and soul. Such efforts a California Indian dislikes even more than manual labor.

Chapter Four—

Of the Churches in California, Their Furnishings and Ornaments

The misery and poverty of California was least apparent in the churches. Although the homes of the missionaries were poorly furnished and the kitchens badly equipped, the churches were richly decorated

and the vestries well supplied with everything. The missionary's kitchen contained a copper pan, a small copper vessel in which to prepare the chocolate, both tinned for the first and last time when they were bought in Mexico; two or three pots made of clay and goat manure, unglazed and only half baked on charcoal in the open air; a small spit, which often remained unused for half a year; and some cow bladders filled with fat. In the rest of the house were to be found a crucifix, some paper pictures on the wall, an adequate library, two or three hard chairs, an equally hard bed without curtains, or in its place, a cattle skin on the bare ground. These items comprised the complete furnishings of kitchen and house. In the churches, however, it was quite different.

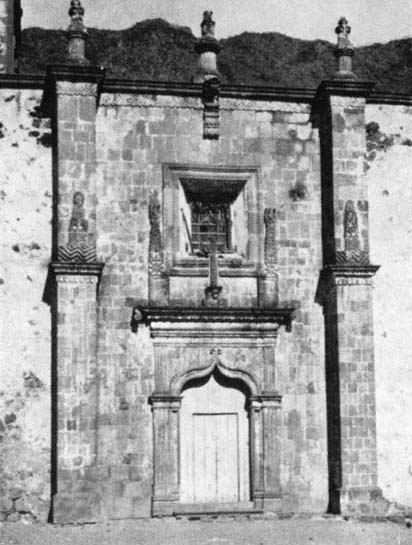

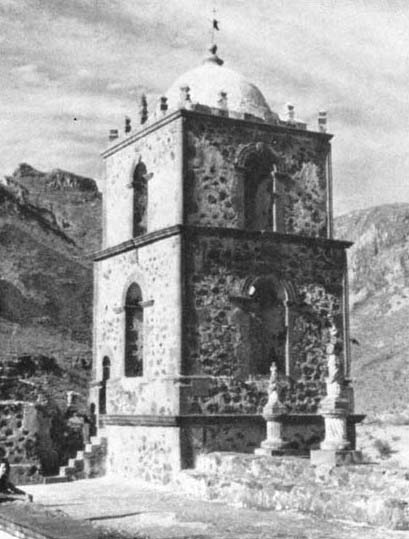

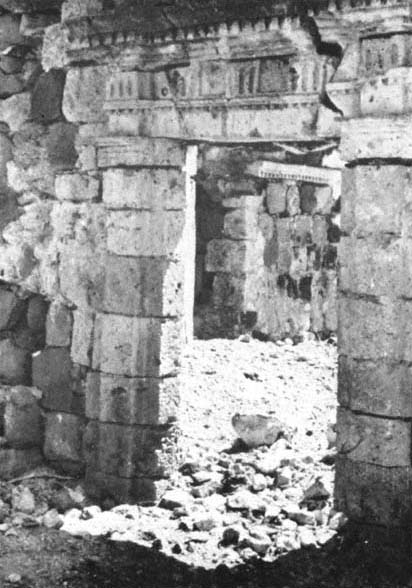

As a rule, the churches were built before any thought was given to housing comfortably its servants. The churches were well and as beautifully constructed as possible. Lime was carried from a distance of many miles, and lacking other material, the hard wacke stones were hewn into cornerstones and frames for doors and windows. The church of Loreto is very large, yet consists only of four artless walls and a flat roof made of well-joined beams of cedar wood. However, no other church could compete with its paintings or in the costliness of its clerical vestments. The vaults of three other churches were made of bricks or tufa stone. A fourth, which in size and artistic beauty was to surpass all others, was about to receive a vault when the architect, a native-born Mexican missionary and builder, was expelled and forced to depart for Europe. From the New World, his native land, he was sent to the Old World and into misery. He was not even told whether the construction of the church or something else was responsible for his banishment. The church of Todos Santos is vaulted, but with wood which was brought to the mission with the help of a great many teams of oxen over many miles from a very steep and high mountain range. It is large, richly and amply decorated. The church of the mission of San Xavier was built like a cross, with three imposing doors and three completely gilded altars, a high tower, a graceful cupola, and large windows, which were the first and only glass windows to be seen in California during those last few years.

No church had less than three bells; but at Loreto, at San Xavier, and at San José Comondú from seven to nine bells can be counted. They do not sound badly when they are rung, or to speak more correctly, when

they are struck, according to Spanish custom. Two churches had organs; a third expected to receive an organ from Mexico. Most of the altars were completely gilded, and the walls were covered with pictures in golden frames.

Aside from a few which were rarely ever used, I, never saw in California a clerical vestment or choir cope which was not silk lined and bordered with good galloons. The material of which they were made was usually very rich and costly, and thirty to forty guilders were paid for a Spanish ell (four spans). Chasuble and antipendia were matched and made of the same cloth.

In all the churches, the steps leading to the altar were covered with carpets (different ones were used on work days, Sundays and high holidays). In one church there was also a carpet for the choir, covering the entire, and not very small, floor; it was used only on the highest holidays.

All chalices, of which each mission had more than two, the ciboria, the monstrances, the little wine and water vessels, the censers, and sometimes the holy water fonts which hang near the entrance, the little altar bells, the two big lamps, the various crucifixes used on the altar and in processions, and more than two dozen big candlesticks for the altar were made of solid silver. A big tabernacle, an antipendium of hammered silver, and a chalice of solid gold can be seen in Loreto, unless they have recently been melted down.

The surplices, humerales, choir robes, and altar cloths were of the finest linen, and many of them were adorned with beautiful white embroidery. None of the surplices, choir robes, and altar covers were without lace, some of it very wide and shot through with threads of gold.

Creditable singing, like beautiful Lauretan litanies, could be heard in some churches. Father Xavier Bischoff,[31] from the county of Glatz in Bohemia, and Father Pietro Nascimben,[32] of Venice, Italy, were particularly responsible for introducing choral singing to California. They had trained the Californians, both men and women, with incomparable effort and patience.

A few questions might now arise in the reader's mind, which, before I proceed further, I should like to answer. First: How is it possible to erect such churches in California? Answer: Building material, like workable stone, lime (and the necessary wood for burning it), is hard to find

at most missions. It takes much effort to transport these and many other materials to the proper places. However, the zeal to serve the glory of God, as well as time, industry, hard work, patience, and a large number of donkeys or mules will overcome all difficulties. Many California natives learned stone masonry and brick laying. A missionary, a carpenter, or a competent soldier supervises the construction, or a master builder from another place is engaged for pay. The common labor is performed by the Indians. While the building is under construction, the natives do not have to roam the fields in search of food, and they are not missed in their household or business anyway. For scaffolding, any kind of rough lumber and poles will do. Should some pieces be too short, then two or more of them are tied together with strips of fresh leather; also the trunks of palm trees are used for scaffolding. When none are available nearby, they are sometimes brought from a distance as much as eighty or more hours away. Instead of constructing the framework for the vault with boards, all sorts of odd pieces of useless wood and the dry skeletons of thorn bushes (described in another place in this book) are used and coated over with clay or mud. Except for the three missions in the south, the land is full of common building stones. It is therefore possible to construct within a few years and with little expense such a respectable California church as would do credit to any European city.

Second: Where did all these treasures come from, such as silver vessels, altars and paintings, since there are no painters, goldsmiths or sculptors, and there is not even a skillful tailor in California? Answer: Everything is imported from the city of Mexico, five to six hundred hours away from California, where there is such a surplus of these artists, artisans, and craftsmen, white and dark, that at times they purposely produce poor work so they may soon get another order. The high altar of San Xavier was sent in thirty-two boxes, piecemeal, and already gilded. The cloth for the church vestments was also imported, but they were made in California. When I was forced to leave California, I was at work on a piece of cloth which cost forty guilders an ell, and hardly any of the silk could be seen in it.

Third: How is it possible to acquire such rich church ornaments in a country as poor as California? The answer to this question and the solution of this riddle I shall withhold until the end of the fifth and the sixth chapter. Meanwhile I will state, however, that such treasures could

be and were purchased thanks to good management. The fervent aim was to induce reverence and respect for the house of God in the newly converted Indians, and also to create among them prestige for the Catholic religious services. It is to be desired that certain gentlemen in Europe—particularly those living in the country—take this as an example. Their houses are incomparably better decorated and equipped with necessary and ornamental fittings than their churches and sacristies, and these gentlemen appear better dressed in public than in front of the altar. Although churches of many villages are poorly endowed and have little or no income, those who attend the services of such a church or own the village get so much more. These gentlemen undoubtedly could win the love of their fellow parishioners and subjects and earn eternal gratitude if they donated some of their surplus to their church, either for the acquisition of a new, clean altar, a neat pulpit and benches, a fine alb, a respectable mass book, or a silver ciborium, or something similar. Thus they might make it possible to throw aside the age-old, worn out, badly torn, shrunk and half-decayed altar vestments, and coarse surplices which have served them and their ancestors long enough.

Chapter Five—

Of Agriculture in California

It says in the Holy Scriptures that the evangelical worker deserves his pay and that he shall eat that which is given to him by the people he instructs and to whom he preaches. But what can the California Indian, who has nothing and who is barely able to ward off starvation, give to his missionary? And how could the latter endure the California victuals for a long period of time without the aid of a miracle? At which market could he buy what he needs? It was, therefore, important that

the first missionaries who lived on the grain and meat they had brought with them from Sonora and Sinaloa, across the sea, should be intent on agriculture and animal husbandry in order to feed themselves and their successors, as well as the soldiers and sailors, the sick Indians and catechumen. Thus, at all missions where conditions permitted, the land was cultivated and livestock was introduced. Concerning land, there is enough of it, even though the soil is hard and full of rocks. But there is not sufficient water. Consequently, water was taken wherever and however it was found. The site for a new mission was determined, if possible, by the availability of at least some water which could be used to irrigate the land, either at the mission, or in a place several miles away. No effort was spared. In some places, water was brought half an hour's distance over irregular terrain through narrow channels or troughs carved out of the rock. At other locations, water was collected from six or twelve places—a handful from each source—and conducted into a single basin. Some swamps were filled with twenty thousand loads of stones and as many loads of earth. And sometimes just as many stones had to be cleared away to make this or that piece of land tillable. Nearly everywhere it was necessary to surround the water as well as the soil with retaining walls or bulwarks, and to erect dams, partly to keep the small amount of water from leaking out, and partly to keep the soil from being washed away by the torrents of rain. Even so, all the work was often useless. At best one had to patch and to repair every year, and sometimes it was necessary to start all over again.

But in spite of all this, and even though not the smallest area of productive land was left to lie fallow, and though the corn ripened twice a year, there was never enough corn and wheat to feed twelve to fifteen hundred adult Californians, or to get along without bringing in several thousand bushels of grain and other requisites from some other place for the sustenance of the soldiers.

The plow of California—and, from what I have seen, also of other districts in America—consists of a piece of iron shaped like a hollow tile, with a long point or beak on one end. On the other end a wooden stick is inserted into the hollow iron, which permits the plowman to guide the plow. It has no wheels, and the oxen drag rather than pull it. After the soil is cut and turned over by the plow, deep furrows are hoed. With a pointed stick, small holes are made on the slanting sides of each

furrow. The wheat is placed in these holes, which are closed by pushing in the dirt with the foot and tamping it down. This is slow work, and much help is required. As soon as the seed is in the ground, the crows arrive and march from one hole to the next. Unless a large number of sentinels are standing guard to ward them off, the birds dig up all the grain.

The mice are even worse than the crows because they work unseen and during the night like other thieves. Thus, many times after half the seed had sprouted, more days were required for a second and third seeding. When the planting was finished, water was run through the furrows once every week throughout the growing season until the kernels began to harden. Grain could be planted all year long, but it was generally done in November. In May the wheat was either cut or the spikes were broken off one by one.

The same system was used for planting corn, beans, and a variety of large Spanish peas called garbanzos (chick-peas), without which the Spaniards cannot live and which they cook together with many other vegetables. As a rule, they are hard when served at mealtime.

Other things grown in California were squash, pumpkins, watermelons, and other melons. In three missions even some rice was raised. Besides these various garden plants, figs, oranges, lemons, pomegranates, bananas, and some olive trees and date palms were grown. Of European and German fruits, there were none in California except a few peach trees. From them, two rather small and stale peaches were once sent to me from a place thirty hours away. At two missions there was sugar cane. At several others cotton was planted, from which summer clothes, stockings, caps, and other things were woven and knitted for the natives.

It was not necessary to buy sacramental wine elsewhere. The land produces it, and without doubt it could become an excellent and generous product if cool cellars, good barrels, and skilled vintners were available, because the grapes are honey-sweet and of superior flavor. Five missions have vineyards. The juice is merely pressed from the grapes by hand and stored in stone jars. These jars hold approximately fifteen measures (one measure is two quarts, approximately) and are left by the ship which makes a yearly visit to California on her way from the Philippine island of Luzón to Acapulco in Mexico. The storage cellar for the wine is an ordinary room on level ground and—in California—

necessarily warm. Therefore usually half of the grape juice, or even more of it, turns to vinegar. Ten or fifteen jars full of sacramental wine were sent each year to the missions across the California Sea and to the four or six missions in California which had no vineyards. When it left the cellar, the wine was good, but it did not always arrive in the same condition because it had to be carried on muleback in the hot sun for fifty or more hours. As a result, the wine often turned sour, sometimes on the way, sometimes soon after it was delivered.

It was not permissible to give wine to the Indians. Some of the missionaries never tasted any except during Mass. One measure of it sold for six florins, so that neither soldier nor sailor could afford to get drunk frequently. Yet there was no aged or choice wine in California.

From these facts it can be seen that only a small quantity of wine was successfully produced. It was not surprising that many times I and my colleagues had no wine, even for the Holy Mass. Yet it has been claimed that the missionaries of California sold much wine and sent it to other lands. The grape vines, as well as the fig and other trees in California, have to be watered just like wheat and corn.

Chapter Six—

Of the Livestock in California

Animal husbandry was the other temporal matter which required much care and thought at the California missions, and without which they could not have survived. For that reason, horses and donkeys, cows and oxen, goats and sheep were brought there in the very beginning. Had any of these animals known about California or how badly they and their offspring would fare in the new colony, they would surely have preferred a hundred times to run away as far as their legs could carry them rather than to let themselves be shipped to California.

Cattle, sheep, and goats had to supply the meat for the healthy and the sick, but they were also needed because their tallow was used to make candles and soap, for ships and boats, and they furnished the fat to prepare the beans. In California as well as elsewhere in America, the beans are not prepared with butter churned from milk, but with the so-called lard or rendered fat and the marrow of the bones. For this purpose, every time a well-fed cow or ox was killed, which was a rare occurrence, every bit of fat was carefully cut from the meat, rendered, and conserved in skin bags and bladders. This fat was used for the preparation of food and for frying the very lean or dried meat. Some of the hides were tanned for shoes and saddles and for bags in which everything was carried from the field to the mission or anywhere else. Other skins were used raw to make sandals for the natives, or were cut into strips for ropes, cords, or thongs, which were used for tying, packing, and other similar tasks. The natives used the horns to scoop up water or to fetch food from the mission.

Without horses or mules it would also have been impossible to exist. They were needed for guarding the cattle and carrying burdens, and also as a means for traveling by the missionary or by the soldier. It would have been difficult to make much progress on foot in such a hot and uneven land.

Sheep too can serve a good purpose for people who have no clothes—if only the flocks had not been so small because of the lack of feed. Moreover, the sheep left a good part of their fleece on the thorns through which they passed. Wherever a flock could be maintained and increased to a good number, there were also spinning wheels and weaving looms, and the people received new outfits more frequently than at other missions. Of pigs, there were hardly a dozen in the whole land, perhaps because they cannot root up the dry, hard ground and have no mud holes to wallow in.

Wherever circumstances permitted it, no labor was spared to plant or seed the ground. Small or large herds of sheep and goats were maintained, as well as a "flying corps" of cows and oxen, and care was taken that horses and mules would not die out.

The goats and sheep returned every evening with full or empty stomachs to their folds. At times it was difficult to extract a pint of milk from six of the goats. The cattle had free passage and were per-

mitted to wander fifteen and more hours in every direction to find their feed. They were brought in only once a year when their tails were trimmed to make halters from the hair. At the same time, the calves born during the last year had a piece clipped off their ears and were branded with a sign, so that they could be identified if they lost their way or strayed into other territory. The same thing was done to colts and young mules.

To keep the livestock from straying too far, or from disappearing entirely, five or six herders were necessary. It was their job to ride one week in one direction, the next week in another, in order to keep the animals closer together. When the herders rode forth, they always took half a legion of horses or mules with them. Then they would go at full gallop over mountains and valleys, over rocks and thorns. Since neither horse nor mule was shod and fodder was so scarce and poor, and since at times the galloping lasted for many days, often weeks in succession, the herders needed to change their mounts many times a day. To protect a few hundred cows, therefore, almost as may horses were required. Hunger alone did not make these animals run so far afield. They also suffered from persecution by the natives, who killed more of them in the open than were brought to the mission for slaughter; nor did the Indians spare horses or mules. They relished the meat of the one as much as that of the other.

All these animals were very small. Scarcely three or four hundred pounds of meat and bones could be obtained from a steer. The milk was only for the calves. I have already reported in another chapter that for nine months of the year the animals were as skinny as dogs and carried not a pound of fat on their bodies. They ate thorns, two inches long, together with stems, as though they were the tastiest of grasses. Thus, except to furnish poor and insufficient food for not too many people, three or four hundred head of such cattle barely paid enough to buy the bread that two Spanish cow herders and their helpers ate in one year. Yet the herders were as essential at some missions as was the livestock. To allow the animals to go unguarded in California was like sending them to the slaughtering bench, or like setting the wolf to guard the sheep.

The goats and sheep were no better off than the cattle, and the laziness of the native herders added a good deal to their hardships.

More than once during these seventeen years have I seen a flock of sheep numbering four to five hundred head reduced by hunger to eighty or even fifty. More than half of this time I received very little from them, because after they were skinned, the carcasses were more fit to be used as lanterns at nighttime than as roasts in the kitchen.

Among the California horses there was one very good strain, agile and hardy. They were small, however, and increased in number very slowly, so that every year others had to be bought outside of California to keep the soldiers mounted. Only the donkey, who is not so fussy and always patient wherever it may be, was fairly well off in California. It worked little and ate the thorns and stalks as though eating the finest oats.

If what I have reported in this and in the preceding chapter about agriculture and animal husbandry in California should lead to the conclusion, or even suggest, that the missionaries sought or found profit in these activities, such would be an error. I knew not one among them who did not regard this work as a heavy burden which he would gladly have slipped from his shoulders. It was definitely a hardship—equal to the services of shiftless soldiers—which had to be endured in order to help the California Indians win the Kingdom of Heaven. Aside from this benefit, the natives derived another profit from the labors of the missionaries. Through small gifts the hearts of a poor, barbarian people could be won, and such gifts saved many of them from pernicious laziness and idle roving.

Furthermore, even if the mountains of California had been made of solid silver, I cannot see what temporal prestige or selfish gain the missionaries could have acquired from such labor and worry, to which they certainly were not accustomed. Voluntarily and irrevocably they left their country, parents, brothers and sisters, friends and acquaintances, and last but not least, an easy life, free from worries, to enter an existence full of a thousand dangers on water and on land. All this they endured so they could, in the New World, in a wilderness, among wild and inhuman people, among disgusting vermin and cruel beasts, live well and gather wealth for others! To judge, to speak, or to write in such a way is not just average stupidity. It is rather to brand as the world's biggest fools a number of intelligent men, of whom it is said and written that they are not lacking in knowledge and reason. In respect to "gathering wealth for others," Father Daniel has already said, a short time ago, that since

Father Baegert's Mission San Luis Gonzaga

Automobile Club of Southern Calafornia

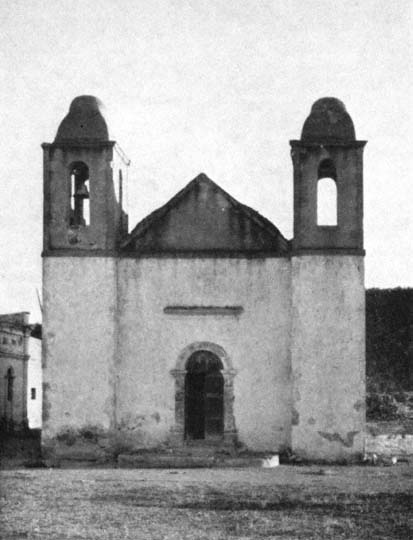

Nuestro Padre San Ignacio de Kadakaamang

Neal R. Harlow

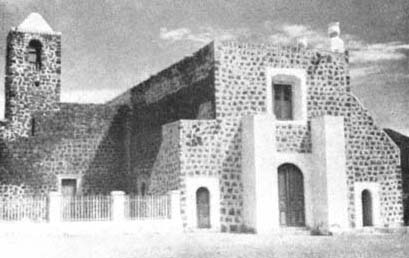

Santa Rosalía de Mulegé

Neal R. Harlow

San Francisco Xavier de Biaundo

Neal R. Harlow

Side Door of Mission San Francisco Xavier

Neal R. Harlow

Tower of Mission San Francisco Xavier

Neal R. Harlow

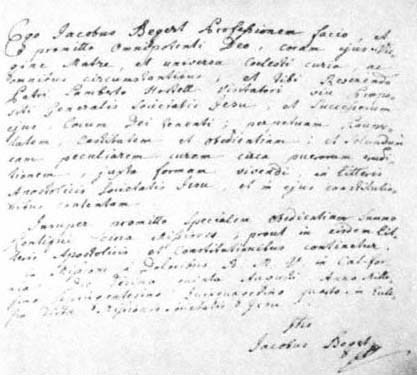

Father Baegert's Profession, August 15, 1754

Archives of the Society of Jesus, Rome

Nuestra Señora de Loreto, Mother Mission of the Californias

Rivera Cambas, Mexico Pintoresco

Ruins of the Chapel of Mission San Juan Londó

Neal R. Harlow

the beginning of the world, no one has ever heard of a band of thieves or robbers in which any of the group chose to live alone in the forests in constant danger of being broken on the wheel, so that the rest of the band might live in the city, well and at ease, and become wealthy from loot.

To tell the truth, for eight years I also had four to five hundred head of cattle and as many sheep and goats running around in California, until the thieving of the Indians from my own and another mission forced me to do away with them. For several years I had a small field of sugar cane in front of my house, until the Indians again went too far and pulled up nearly all of it before it was ripe. In six or seven years I gathered several thousand bushels of grain—corn and wheat—from the six or seven small pieces of land which I had caused to be planted here and there. Yet most of the time I had no bread in my house. And when I wished to honor a guest, I had to request a fowl from one of my soldiers—who kept a few chickens on his own corn rations—while I saved my wheat and corn for needy Indians. In my kitchen I also used suet, even on days of fasting, because I had no butter. In many years I hardly tasted meat other than that of lean bulls, which were killed every fourteen days. I never had veal. I seldom saw my roasting spit on the table, although more than once I saw maggots there. Finally, not to mention many other things, I often found myself forced to give up the evening meal entirely because I had nothing I cared to eat. For several years I fasted for forty days on dry vegetables and salted fish five or six times within twelve months. To let the fish swim in their element, my drink was precious, although not always the freshest, water.

Several times I could have changed my post and gone to another place where, I am sure, I would have found better food and many other things I did not have, but it was not very hard for me to resist the temptation. In California the missionary has small regard for temporal goods or personal advantages.

Now is the time to answer the third question in Part Three, chapter four, as I have promised to do. How then was it possible, in a poor land like California, to acquire such beautiful and rich church ornaments? Answer: It was possible to acquire them: first, from the thousand florins or more per year which represented the income from the endowed estates to each mission; second, from the sale of wheat and corn, wine and

brandy (the latter was distilled from wine which was about to turn to vinegar), sugar, dried figs and grapes, cotton, meat, candles, soap, fat, leather, horses, and mules, all being products grown or made at the missions. These exceeded what the missionary needed for the support of the mission, and were sold to the soldiers, sailors, and miners. These sales could hardly have been refused, especially in cases of necessity, when crops had failed outside of California. Furthermore, whatever was of no value to the Indians was sold. Finally, everything a missionary could have but did not use for his own person, that is to say, what he denied himself, was also sold. Soldiers and other people often drank wine which the missionary could have enjoyed himself without drinking to excess. A good deal of this income was used to supply the Indians with clothes and provisions which they lacked and which had to be purchased. With the remainder the above-mentioned costly church ornaments were acquired little by little.

If anyone wishes to find fault with such expenditures or wishes to raise his voice against them—like the traitor Judas against the extravagance of Magdalene (John XII)—as someone has done in the Spanish language, although not about the California missions but about the churches of a certain religious order in general, and if he be a Christian, a Catholic Christian, I refer him to the words in Psalm XXV: "Domine, dilexi decorem domus tuæ." (Lord, I have striven for the beauty and adornment of thy house.) I wish also to advise him to look homeward concerning extravagance, and to criticize the silver dishes, tapestries, and the like found nowadays in private homes before he censures the ornaments in the houses of the Lord.

Leave to the Lutherans and Calvinists—until God will convert them—their austere altars, their bare walls and empty barns, and let us beautify our churches as true houses of God, as best we can. Those who do not care to contribute should leave other people who desire to do so unmolested.

It was impossible to use all the revenue from animal breeding or agriculture for the benefit of the Indians. They were poor, so poor that their poverty could not be greater, but their poverty is of a different nature and character from that prevalent among so many people in Europe. An Indian cannot be helped by paying his debts or by releasing him from prison, by giving money to a girl so that she might enter a con-

vent or be married. It is not necessary to pay their rent or buy their freedom from servitude, pay their doctor or apothecary bill. For the California Indian, everything centers on food and clothing. With these two necessities the missions were well provided through agriculture and livestock breeding. They could, considering the standards of the native, give them all the help they needed. There was no other use for the surplus than to adorn the churches, to make the service of the Lord impressive and dignified, and to console the servants of the Church through the greater honor of their God and through the edification of their fellow men.

Finally, because I have spoken several times of "bread" in this little work, I must make it clear to the reader that I did not speak of bread made of wheat or corn flour, but of little pancakes made of corn meal. The corn is lightly boiled, then ground by hand between two stones. The meal is formed into thin, flat, little cakes, made warm over a hot iron plate. These pancakes are eaten by all the people in all America, and are served like warm bread with meat and other foods. I found them a healthful food and very pleasing to the taste after having eaten them for several weeks.

Chapter Seven—

Of the Soldiers, Sailors, Craftsmen, as well as of Buying and Selling in California

The entire Second Part of these reports dealt with the black-brown natives of the California peninsula, and in the First Part all that is essential about a handful of silver miners has been told. What remains is to report about some other white men who are living in California.

It would be foolhardy to go and preach the Gospel to these half-

human Americans without taking along a bodyguard. It would even be daring to live without protection among those already baptized, because of their vacillating and changeable character. The only thing a missionary without protection could expect to find among these people is an untimely death and the loss of the expense of such a long journey. For this reason, the Catholic Kings have recently issued a decree forbidding a missionary to venture among these heathen without sufficient escort of armed guards. In all the new missions one or more soldiers have to be maintained at the expense of the king. Therefore Father Salvatierra supported as many soldiers as were deemed necessary to keep the newly converted natives and the neighboring heathen in check and to put down possible revolts; or, to state it correctly, he maintained as many soldiers as the alms he received permitted. This situation lasted until 1716, when for the first time the soldiers received their pay from the King of Spain. At that time there were twenty-five of them. However, owing to the serious revolts which broke out at different places, particularly in the southern part of California, and after two missionaries had been killed by the Pericúes, the number of soldiers, including the officers, was finally increased by royal order to sixty men.

These men are not regular soldiers. They know nothing of military exercises; they ask for and receive their discharge whenever they desire it. They are in every respect inexperienced, ignorant, and clumsy fellows born in America of Spanish parents.[*]

Their officers are a captain, a lieutenant, a sergeant, and an ensign. Their weapons are a sword, a musket, a shield, and an armor of four layers of tanned, white deerskin, which covers the entire body like a sleeveless coat. Otherwise they wear whatever they like; they have no uniforms. They serve on horseback or on mule, and because of the rugged trails, each man is obliged to keep five mounts. The soldiers have to buy these animals as well as their weapons, clothing, ammunition, and all their food. Their annual pay amounts to eight hundred and fifty guilders.

Their duties are these: to serve the missionary as a bodyguard, to

[*] One of them asked me, after reciting the Rosary, "What is an hour?" Another remarked, while we were riding through a territory full of great masses of stones in the plain and in the mountains, "God must have worked hard bringing so many stones to the surface."

accompany him on all his travels, to keep watch during the night, to keep an eye on the Indians, and if a crime is committed, to carry out the punishment. They take turns riding out every day to see that their or the missionary's horses do not stray, for these animals roam freely in the field. And finally, the soldiers have to obey the missionary in everything which concerns good discipline and the affairs of the mission. Such were the wise and beneficial orders issued by the Catholic Kings, Philip V and Ferdinand VI. These orders keep the soldiers from roving through the land at will, using the Indians and their wives for pearl fishing and for other work, or abusing them in any other way.

A certain Viceroy of Mexico[33] changed these provisions, but after a short time of confusion, he found himself compelled to reestablish the old order.

To increase the dependence of the soldiers and to make sure of their obedience to the missionary in matters mentioned before, the two kings also authorized the missionary to send all those who misbehaved and were more troublesome than useful back to their captain in Loreto without giving them any previous warning. It was also ordered that the soldiers were to receive their pay from the head of the missions or his representative at the place. All these precautions were not adequate, however, to keep such people within the limits of decent behavior. In the course of only a few years, I had to send at least two dozen of these men back to Loreto, though as a rule there were only three or four soldiers stationed at my mission. Yet these regulations were better than having none at all. Imagine what would happen if these soldiers possessed complete freedom at the missions and were permitted to do or go where they pleased or to visit anyone anywhere and at any time!

The same arrangement regarding the pay of the soldiers also applied to the sailors, of whom there were only about twenty. Every year in April these men sailed from California to Matanchel in two small sloops (these and three of four rowboats made up the entire California navy). They brought back Mexican goods and wood, so that the cabinet-makers and carpenters could repair the ships. Several times a year the ships went across the gulf to Sinaloa. They returned with Indian corn, dried vegetables, and also meat, fat, horses, and mules.