Vesuvius

The ejecta deposits of another long-active and much-studied volcano, Vesuvius, indicate that hydrovolcanic activity is significant during its eruptive cycles (Barberi et al., 1981; Rosi and Santacroce, 1983). The AD 79 eruptions of Vesuvius are among its best documented in terms of actual observations (Pliny the Younger, 1763; Radice, 1972), deposit descriptions (Sigurdsson et al ., 1985), and interpretations of eruption mechanisms (Sheridan et al ., 1981). Figure 2.18 shows representative tephra stratigraphic sections from archaeological excavations at three Roman sites that were devastated by

Fig. 2.13

Wairakei Formation tephra stratigraphy for

locations within 20 km of the vent in Lake

Taupo, New Zealand. Members 4 and 6 (m4,m6)

were previously named the Oruanui Pumice

Breccia and Wairakei Breccia, respectively.

(Adapted from Self, 1983.)

Fig. 2.14

Grain-size characteristics of the Wairakei Formation (Self, 1983). (a)Median diameter (Mdf ) ) vs sorting

coefficient (sf ) is shown for the various members (m1,m2,..) illustrated in Fig. 2.13; also noted are

textural types, including accretionary lapilli (crushed), lithic/pumice-rich ignimbrite, and base surge.

The dashed field represents pyroclastic flows. (Adapted from Wright et al ., 1981.) (b) Grain-size

fractions for m4 and m6: the dashed field represents pyroclastic flows; coarse variant shown by

symbols. (Adapted from Walker et al., 1980.) (c) Grain diameter frequency curves for fallout products

of m2 and m6 show gradual loss of coarse products with increasing distances from the source

(curve numbers in kilometers). (d) Cumulative probability distribution of size fractions (f ) for Plinian

and phreatoplinian deposits is compared to the distribution of a representative m3 sample.

(Adapted from Carey and Sigurdsson, 1982, and Walker, 1981.)

the eruptions. Fallout deposits of white and gray pumice from early magmatic eruptions were followed by hydromagmatic products emplaced as surges, pyroclastic flows, and lahars—all containing abundant lithic ejecta derived from carbonate aquifer rocks that underline the Somma Vesuvius at a >2-km depth. Figure 2.19, the model presented by Sheridan et al . (1981), interprets the stratigraphy and illustrates the effects of hydrovolcanic activity during the devastating phases of the eruption. Accretionary lapilli, abundant in the upper portions of the tephra stratigraphy, were studied in detail by

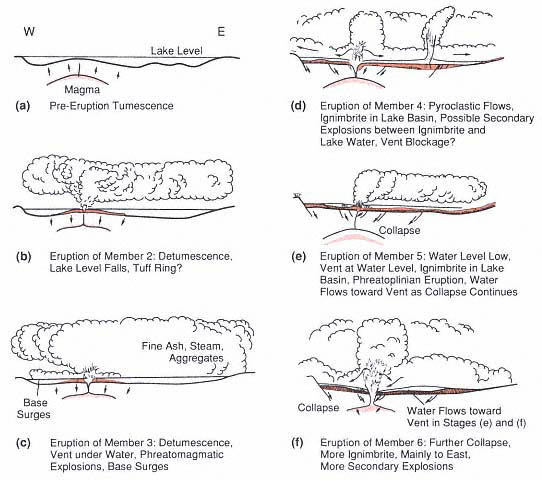

Fig. 2.15

Wairakei eruption model showing the sequential stages or eruption of the various

members and periods of lake water/magma interaction.

(Adapted from Self, 1983.)

Sheridan and Wohletz (1983b), who described possible mechanisms for their formation in wet eruption plumes.

Contrasting hydrovolcanic behavior is evident in the early-stage interaction with water at Vulcano and the late-stage interaction shown at Vesuvius. One general explanation for this contrast is the overall hydrologic setting of these volcanoes: Vulcano is an island edifice characterized by abundant near-surface groundwater, whereas Vesuvius is built on a sedimentary platform with a deep aquifer system. Access of water to the vent system at Vulcano gradually decreases during eruptive episodes as magma congeals along vent walls where water initially infiltrates. At Vesuvius, access of groundwater to the magma chamber and vent conduit is initially limited by thermal metamorphic rocks that have sealed fractures. However, as the conduit and chamber wall rocks are fractured by expansion of magmatic gases early in Plinian eruptive episodes, groundwater gains access to the magma, especially after overpressures in the magma body and conduit have fallen below the local thermally perturbed hydrostatic

Fig. 2.16

Composite stratigraphic section illustrates

the hydrovolcanic cycles of the Fossa volcano

at Vulcano, Italy. The Pietre Nere, Palizzi,

Commenda, and Pietre Cotte cycles all show

a progression from hydrovolcanic eruptions to

emplacement of lava flows.

(Adapted from Frazzetta et al ., 1983.)

pressure. The behaviors exhibited at Vulcano and Vesuvius are generally termed shallow and deep hydrovolcanic eruptions, respectively; the former becomes dryer and the latter becomes wetter as eruptions progress.

Throughout the entire Latium volcanic province of Italy, hydrovolcanism has been a vital component in the development of caldera complexes such as those of Vulsini, Vico, Sabatini, Albani, and the Phlegraen Fields. Broad, low-profile calderas with widespread, fine-grained silicic tephra characterize these volcanic areas. Because of their geothermal importance, we will describe them in detail in Chapter 4.