Gonds

Among the tribal populations of India the Gonds stand out by their numbers, the vast expanse of their habitat, and their historical importance. No exact figures for the present size of the group of Gond tribes is available, for the census of 1961 was the last in which all individual tribes were enumerated. At that time 3,992,905 persons were returned as Gond, and there can be little doubt that by now the number of Gonds must long ago have exceeded the four million mark. Figures for the speakers of tribal languages are still being published, and in 1971, 1,548,070 Gondi-speakers were recorded. But this does not give an indication of the present strength of the ethnic group embracing the various Gond tribes, for more than half of all Gonds speak languages other than Gondi, such as Chhattisgarhi Hindi, an Aryan tongue which must have replaced the Dravidian Gondi.

The majority of Gonds are found today in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Their main concentrations are the Satpura Plateau, where the western type of Gondi is spoken, and the district of Mandla, where the Gonds have adopted the local dialect of Hindi. The former princely state of Bastar, now included in Madhya Pradesh, is the home of three important Gond groups, namely, the Murias, the Hill Marias, and the so-called Bisonhorn Marias, all of whom speak Gondi dialects. The states of Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh also contain substantial Gond populations, and the majority of these have traditionally been described as Raj Gonds, though in their own language they call themselves Koitur , a word common to most Gondi dialects. The term Raj Gonds , which in the 1940s was still widely used, has now become almost obsolete, probably because of the political eclipse of the Gond rajas. The rulers of Chanda, situated now in Maharashtra, were until 1749 powerful princes whose dominion included a large part of the Adilabad District of Andhra Pradesh. The rule of the Gond rajas of several princely states in Chhattisgarh lasted until 1947, when the British withdrew from India and the Gond states were merged with Madhya Pradesh.

There exists little accurate information on the early history of the Gonds, and it was not until Mughal times that Gond states figured in contemporary chronicles. But the ruins of forts ascribed to Gond rajas suggest that in past centuries the Raj Gonds did not live in the isolation typical of many other tribal communities but entertained manifold relations with other populations whose style of living their rulers imitated. Until comparatively recent times, a feudal system prevailed also in the highlands of Adilabad, and myths and epics depict the life of Gond chieftains who were not subject to any outside power. The Gonds were then already settled farmers who cultivated their land

with ploughs and bullocks. Land was plentiful, and individuals could freely move from one settlement to another. In the following chapters we shall see that this mobility has now come to an end, and with this the entire life-style of the Gonds has changed.

Gond society has both its vertical stratification and its horizontal divisions, and while with the decline of the raja families the stratification based on hereditary rank has been reduced in relevance, the division of society into exogamous patrilineal units has retained its importance. The basis of the social structure is a system of four phratries, each subdivided into clans, and the origin of this system is attributed to a divine culture hero. The members of each clan worship a deity described as persa pen ("great god"), and in some cases the shrine of this deity lies within the ancestral clan land. Today the clans are widely dispersed, but they still form a permanent framework which regulates marriage and many ritual relations.

Closely linked with each individual Gond clan is a lineage of Pardhans, bards and chroniclers, who play a vital role in the worship of the clan deity and many other ritual activities. The Pardhans, though themselves not Gonds and of a social status lower than that of their Gond patrons, are nevertheless the guardians of Gond tradition and religious lore. The recent deflection of their interests and energy to other enterprises will undoubtedly have an adverse effect on the preservation of Gond traditions.

A role similar to that of Pardhans is being played by another and much less numerous group of bards and minstrels known as Toti. These too have hereditary ritual relations with individual Gond lineages and act as musicians and story-tellers.

The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh, whose fortunes in recent years are the subject of a large part of this book, are only one of the many sections of the Gond race, and differ in cultural characteristics from the various Gond groups inhabiting the hill country of Bastar, which lies due east of Adilabad.

The Gond tribes of Bastar are themselves by no means uniform. The Hill Marias, a population of some 15,000 concentrated in the Abujhmar Hills, are slash-and-burn cultivators, and their agricultural methods resemble those of Konda Reddis and Kolams. Each group occupies a territory within which its members shift their settlements as well as their fields every few years, returning after some time to the same village sites. A few communities of Hill Marias have moved across the state boundary into the Bhamragarh region of Chandrapur District. Those who live in the high hills continue their traditional way of life, but in recent years quite a number have migrated to lower ground. There they have learnt plough cultivation from the local plains people, and now grow rice on rain-fed fields.

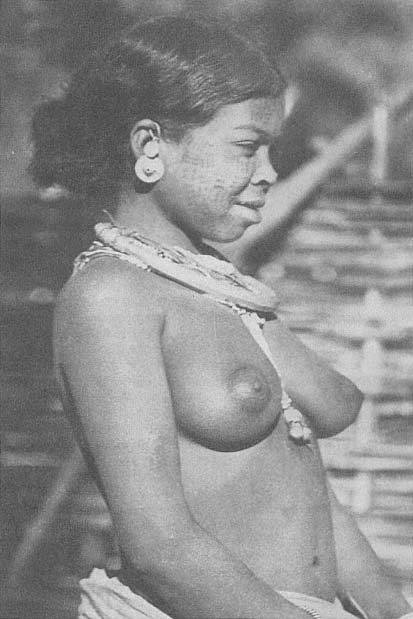

Hill Maria woman with extensive face tattoo wearing a hollow necklace

of white metal and silver ear-rings.

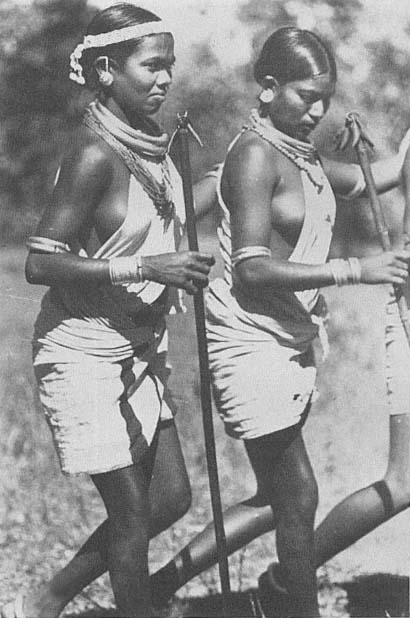

Hill Maria girl wearing silver nose-studs and ear-rings, and several strings

of glass beads.

Bisonhorn Maria girls of Bastar during a dance, wielding sticks with rattles

attached; their necklaces and armlets are made of white metal.

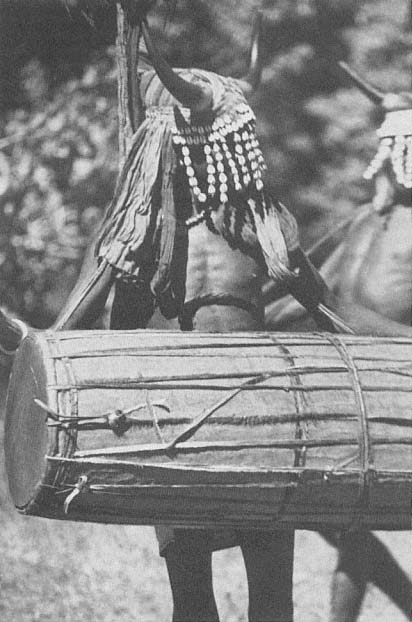

Bisonhorn Maria dancer with a mask of cowrie shells playing a large cylindrical drum.

Far more numerous than the Hill Marias of the Abujhmar Hills are the Dandami, or Bisonhorn Marias, with a population of over two hundred thousand, spread over a large part of Southern Bastar, including the hills of Dantewara, the forest lands of Bijapur, and the low country of the Kutru, Sukma, and Konta regions. The designation Bisonhorn Marias , which has become current in the ethnographic literature, is derived from a distinctive head-dress adorned with the horns of wild bison and worn at marriage dances. These Marias are more settled than the Hill Marias and farm their land in a manner similar to that prevailing among the Raj Gonds of Adilabad. Like the latter they have a cult of clan gods, each of whom is connected with a traditional clan territory. The system of phratries subdivided into clans, so characteristic of the Raj Gonds, extends also to the Bisonhorn Marias.

Distinct from Hill and Bisonhorn Marias are the Murias, a Gond tribe spread over an extensive region in Northern Bastar. The most distinctive feature of the Murias is the ghotul or youth dormitory, and it is due to this institution, reminiscent of the youth dormitories of the Oraons in Bihar and most Naga tribes, that the Murias have a special place in anthropological writings on Indian tribal societies. Their compact villages are distinguished by spacious houses more solid than the dwellings of most other Gond groups. Their principal crop is rice, cultivated on permanent fields, usually embanked and irrigated, but where level land is scarce they also practise slash-and-burn cultivation on hill slopes, and much speaks for the probability that this was the original type of tillage before the Murias acquired ploughs and bullocks. Today the Murias of the Narainpur Taluk are among the most prosperous Gond communities.

The Koyas, a tribal population largely, though not exclusively, concentrated in Andhra Pradesh, are the southernmost section of the great Gond race. Known also as Dorla Koitur, they merge on the southern border of Bastar with the Bisonhorn Marias, and some groups of Koyas, notably those in the lower Godavari regions, also possess bisonhorn head-dresses. In that area Koyas still speak a Gondi dialect, but the majority of Koyas have lost their own language and now speak the Telugu of their Hindu neighborus. In the districts of Khammam and Warangal, Koyas make up the majority of the tribal population. There they have suffered a fate similar to that of the Gonds of Adilabad District, in the sense that they have lost much of their best land, which they used to cultivate with ploughs and bullocks, and are largely reduced to the role of tenants and agricultural labourers. The process of detribalization has progressed further among Koyas than among any other Gond tribe.

Bibliography

Elwin, Verrier. Maria Murder and Suicide. Bombay, 1943.

——. The Muria and Their Ghotul. Bombay, 1947.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Raj Gonds of Adilabad. London, 1948.

——. The Gonds of Andhra Pradesh. Delhi/London, 1979.

Grigson, Sir Wilfrid. The Maria Gonds of Bastar. London, 1949.

Jay, Edward J. A Tribal Village of Middle India. Calcutta, 1970.

Rao, P. Setu Madhava. Among the Gonds of Adilabad. Hyderabad, 1949.