Seven—

Loving and Working

DUCHAMP'S STRATEGIES for undermining his own personal coherence, employing self-contradiction as a weapon against consistency and celebrating chance as a solvent of predictability, have encouraged some critics to regard his life as irrelevant to his work. And yet his campaign to bring art back into the sphere of everyday existence suggests just the opposite, that his way of living was an essential part of his career as an artist. How closely was Duchamp's work tied to his life? Having found some persistent preoccupations in the work, we can approach this question by seeing whether they correspond to themes in his life, beginning with a subject to which his work constantly returns, sexuality. It is not an easy topic to explore, because much of Duchamp's adult sexual history remains obscure and mysterious, and the materials for piecing it together are both fragmentary and suspect, sometimes intentionally veiled or limited by reticence and discretion, and sometimes colored by the desire of his friends to idealize one or another side of his personality. All the same, Duchamp's life as a lover seems to follow certain patterns, formed out of a curious combination of erotic excitement on the one side and indifference or even renunciation on the other.

Of his romantic connections, one of the best documented and most intriguing is his relationship with Beatrice Wood, the spirited and at-

tractive young actress and aspiring artist (she became a well-known ceramicist) he met during his first months in New York. From a wealthy and cultured family, Wood had lived in Paris just before the war; in America she appeared in French plays, and her ability to speak French was an important tie to Duchamp at a time when he still had rather little English. (Although he had begun to learn the language while accompanying his sister Yvonne to England in 1913, he arrived in New York able to speak only halting sentences.) She later gave a number of different accounts of their liaison, but we will follow the most complete, since it is also the one whose details best match what we learn from others who knew her and Duchamp at the time.[1]

Their first encounter took place when both were visiting the composer Edgard Varèse, in hospital on account of a broken leg. Duchamp's presence immediately overwhelmed her, first because of his "extraordinary" face and his "luminous" personality, then because of the powerful wave of attention he directed toward her, talking about her interests, encouraging her to draw, and almost immediately addressing her with the familiar tu . "At that moment we were lovers."[2]

Except that they were not lovers, certainly not then, and possibly never. Most accounts of Duchamp's life assume that a physical relationship followed, and Wood herself said as much, but just what she meant remains murky and uncertain. Following that first meeting the two were often together, Wood visiting his studio and feigning a greater interest in drawing than she felt, "as an excuse to be near him." She went out in his company, and he introduced her with pride at the Arensbergs, giving an impression that may have deceived some: "Though we acted like lovers from the moment we met, the act itself did not occur for quite some time. It was not necessary."

Instead, Wood began an affair—her first—with Duchamp's new friend, the diplomat and art dealer (he later became better known as a novelist) Henri-Pierre Roché; this did not stop her from dreaming about Duchamp or telling Roché about her state of mind, which did not displease him, "for he too loved Marcel." The three commenced what she called a relationship à trois , meaning that they met regularly in cafés, studios, salons, and galleries; all had a part in submitting the urinal dubbed Fountain to the 1917 Independents show and in publi-

cizing the episode afterward. Before long, however, Roché began to find interest in other women, leaving Wood "crushed"; he departed on a visit to Paris "and, like tides moving towards the moon, Marcel and I became closer." But tides never reach the moon; what about Wood and Duchamp? Her words are again both clear and confusing: "A physical relationship was inevitable. But he still continued to utter the same words [ones he first used about the objects she saw in his studio], a phrase that he would repeat time and time again, 'Cela n'a pas d'importance.'"

Does Wood mean that the "inevitable" physical relationship in fact occurred or not? Here is her summary comment on Duchamp's personality:

There is a wonderful Indian saying that the eyes cannot see until they are incapable of tears. Marcel's saying that "nothing has importance" somehow reflects the same idea. It was as if he had gone through all the trials of the flesh and left that behind. With his grave perception, did he realize that, in the long space of time, nothing really mattered? He had the objectivity of a guru. His mind touched stillness, beholding the unity of life. Yet with this understanding went a certain deadness. Many have observed it. The upper part of his face was alive, the lower part lifeless. It was as if he suffered an unspeakable trauma in his youth.[3]

If Duchamp had "gone through all the trials of the flesh and left that behind," then in what did his intimacy with Wood consist? Is she saying that intimacy with him did not require physical fulfillment, since "nothing really mattered"? At the very least, her account depicts a Duchamp whose way of being a lover was strangely uninvolved. In a later interview Wood repeated her declaration that the two "became intimate" after her affair with Roché ended, but she made it harder to take the words in the usual sense: his personality was enchanting, but—lowering her hand from the bridge of her nose—"he was dead from here down. I wondered if he had had a childhood shock."[4]

Given what else we know about Duchamp's amorous life, it seems likely enough that he and Wood did have some sort of physical rela-

tionship; yet in some way it must have involved the "deadness" to which she repeatedly refers, and perhaps we ought not wholly exclude the possibility that her descriptions of the two as lovers should all be taken in the sense she gave the phrase when she used it about the strong current of feeling generated by their first encounter. What makes her account so striking is the way it links together the two modes of erotic life that often recur in his work, one an intense, even pressured flow of sexual feeling and desire, the second a cool, distant recursion of sexuality into a space of delay. Whatever may have actually happened between Duchamp and Beatrice Wood, something in their erotic relationship throve on the deferral of its physical outcome, consisting rather in the erotic charge that drew two people together across a distance that they may never have entirely traversed.

Duchamp seems to have had similar relations with other women in New York. Ettie Stettheimer was one of three sisters whom Duchamp met in the Arensberg circle, members of a wealthy banking family and hostesses of a salon on West Seventy-sixth Street that its devotees liked to compare to famous European gatherings—certainly the sisters' models. Ettie was the most intellectual of the three, with a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Freiburg (she wrote her dissertation on William James); Florine was a painter who received some critical approval but never any commercial success, while Carrie, the most domestic, oversaw the house and raised money for charities. (An outgrowth of her charitable work was the remarkable dollhouse on which she worked for several years, and which can still be seen in the Museum of the City of New York, decorated with miniatures of modernist paintings given by her artist friends, including a tiny version of the Nude Descending a Staircase provided by Duchamp.)[5]

Although friendly with all three sisters, Duchamp was closest to Ettie, and some who knew them thought a full-blown romance, perhaps even marriage, was in the air. Such a possibility seems to lurk in the account Ettie gave of their friendship in her second novel, Love Days , published in 1923 (but mostly written two years earlier), where Duchamp appeared—as he knew very well himself—under the pseudonym "Pierre Delaire," a French artist characterized by his rejection of convention and his love of chance and adventure. "Pierre" is a fasci-

nating companion by dint of the wit and energy he invests in friendship, but the intimacy this seems to promise for Ettie's alter ego in the novel never arrives, leaving her puzzled by his surprising absence of emotionality, "his strange tendency—strange in so positive a personality—to be neutral in relationships, so to say." She too found that Duchamp generated an erotic excitement that promised something more than it delivered.[6] A young woman whom we know only as Hazel seems to have had a comparable experience with Duchamp. According to Man Ray, who thought the story worth recording in his autobiography, she played the piano in the Pepper Pot, a Greenwich Village restaurant much frequented by artists, and when Duchamp was there she "could not take her eyes off" him; but he passed his time playing chess. "She asked whether I knew Duchamp well; he was such a strange man, had responded to her advances at first, was very affectionate, but had long periods of indifference."[7] Perhaps Duchamp was simply not very much attracted to Hazel, but Man Ray may have included her story because he recognized—without saying so—its connections with other things he remembered about his friend.

Of these the most striking concerns Duchamp's first marriage, which took place in June of 1927, in Paris, and ended effectively by the following October, although the divorce did not take place until January of 1928. His wife was Lydie Sarrazin-Levassor, a young woman of good bourgeois family (enriched by the automobile industry), somehow connected to Francis Picabia, and Duchamp later said that the marriage had been "half made" by the latter, adding that "we were married the way one is usually married, but it didn't take, because I saw that marriage was as boring as anything."[8]

Many of Duchamp's friends were surprised, even shocked by the news of his marriage, first because it was carried out with all the traditional trappings, civil ceremony one day, church wedding with attendants and formal clothes the next (Man Ray, who agreed to take pictures at the wedding, later described the bride as sailing along like a white cloud and Duchamp "looking spare and gaunt beside her"), lavish reception and presents; and second because Lydie's charms were not easily visible—"Rubenesque" was one polite way to speak about her appearance (Carrie Stettheimer just called her "very fat"). Duchamp

himself described her in a letter to Katherine Dreier as "not especially beautiful nor attractive," but added that she "seems to have rather a mind which might understand how I can stand marriage." And he concluded: "Whether I am making a mistake or not is of little importance as I don't think anything can stop me from changing altogether in a very short time if necessary."[9]

Indeed the time was short. The couple lived in Paris for two months, crowded into Duchamp's small studio in the Rue Larrey. Whether the absence of a honeymoon was due to lack of funds (the income settled on Lydie by her family was rather modest) or to Duchamp's involvement in chess is not clear, but things seemed to go more or less smoothly at first, with Duchamp describing marriage in one letter as "a charming experience so far." But he added that it had not changed his life "in any way," and when a separate apartment was found for Lydie it was clear that Duchamp had no intention of sharing it with her.[10] In mid-August the two left together on a trip to Mougins, in the south of France, near Nice, where Duchamp was scheduled to play in a chess tournament. Here the story took the following turn, according to Man Ray:

I had it from Picabia afterwards that things did not run too smoothly. After dinner, Duchamp would take the bus to Nice to play at a chess circle and return late with Lydie lying awake waiting for him. Even so, he did not go to bed immediately, but set up the chess pieces to study the position of a game he had been playing. First thing in the morning when he arose, he went to the chessboard to make a move he had thought out during the night. But the piece could not be moved—during the night Lydie had arisen and glued down all the pieces. When they returned to Paris, Duchamp told me that there was no change in his way of living; he kept his studio and slept there, while Lydie stayed with her family until they could find a suitable apartment.... A few months later Duchamp and Lydie divorced, and he returned to the States.[11]

Of course, we don't really know that the story is true, but no one seems ever to have denied it; nor does it tell us much about the couple's physi-

cal relations in the first weeks of the marriage, which may have been perfectly ordinary. However that may be, Duchamp's marriage shares with some of his other attachments an unusually well-developed ability to combine erotic expectations with elaborate barriers to their fulfillment.

Some of the evidence we have suggests that the strong current of sexual interest and desire often visible in Duchamp's life flowed in fairly ordinary ways, without being diverted toward distancing or renunciation. He told Pierre Cabanne that as a young man his attitude toward women had been "exceedingly normal," and he explained his insistence on remaining single for most of his life by adding that "One can have all the women one wants. One isn't obliged to marry them." Man Ray told of sitting with his old friend on a Spanish beach in 1961, gazing at bikini-clad young women and thinking "of the naked women we have held in our arms."[12] When he went to Buenos Aires in 1918 he took with him Yvonne Crotti, the recently divorced wife of his friend and about-to-be brother-in-law Jean Crotti, he also appears to have lived with her in Paris during 1921. In addition, it seems—if Jacques Caumont and Jennifer Gough-Cooper are right—that Duchamp had a daughter with a woman who posed for one of the figures in the early picture The Bush , Jeanne Serre. Born in 1911, the child, named Yvonne, was accepted by Serre's husband; she eventually became a painter, and seems to have been told that Duchamp was her father only late in her life; he may have known about her existence for longer, and-accompanied by his second wife, who is reported to have seen a likeness between them-visited her in Paris in 1966. Finally, according to one report, another of Duchamp's mistresses, Yvonne Fressingeas, arranged for him to spend an orgiastic night together with her and two other young women—all three awaiting him, nude and tipsy, on his arrival at her room after midnight—in July 1924.[13]

Yet none of these stories or incidents speaks very clearly about the nature of Duchamp's sexuality, and some of them may veil the presence of something less easy to avow alongside the erotic intensity. He made his claim to have been "exceedingly normal" in response to Cabanne's question about whether the fact that he had been known as "the bachelor" in his mid-twenties (I do not know where Cabanne got this report)

meant he harbored a dislike of women; as for the claim that "one can have all the women one wants," there would seem to be a bit of bravado in it: taken literally it might refer better to "having" women in the way that the bachelors "had" the bride or Duchamp "had" the woman in Dulcinea than to actual sex. Duchamp may have held naked women in his arms and still had relations with them that partook of the "deadness" about which Beatrice Wood spoke. Exactly what his relations with Yvonne Crotti were in 1918 or later I do not know, but she left the Argentine capital several months before he did, unbearably bored by the city's social life and apparently finding no compensation for it in her relations with Duchamp—who, it should be added, failed to mention her departure in his letters to the Arensbergs, which speak mostly about his mounting passion for and involvement in chess, the game whose role in the brief story of his first marriage we have already encountered.[14]

Certainly the existence of the daughter—whether Duchamp was really the father or Jeanne Serre only thought so—seems to prove Duchamp capable of paternity, but by itself it does not tell us anything about the sexuality involved in conceiving the baby. Jeanne Serre's child was born in 1911, so that the time between conception and birth corresponded precisely with the months when Duchamp did the pictures Paradise and Young Man and Girl in Spring , with their evocations of the disappointment that comes with sexual fulfillment and of the pleasures of erotic excitement still tinged with innocence and uncertainty. As for the orgy in 1924, it may well have taken place, but we know about it from Henri-Pierre Roché, who also engineered it and hurried the next morning to interview Yvonne Fressingeas about how it had come off, so that he could write about it in the diary on which he later drew for his novels.[15] His interest in Duchamp's sexuality needs a word to itself.

Roché, the friend who became Beatrice Wood's lover when Duchamp would not, was fascinated by Duchamp's relations with women and wrote about them twice, first in a brief memoir that appeared in 1953 (it was later included in the book Robert Lebel published about Duchamp in 1959), and then in some scenes from a projected novel, never completed, but the manuscript of which was issued after his

death in 1977. (Another novel, Jules and Jim , written before the one about Duchamp and published in 1953, was made into a well-known film by François Truffaut.) Roché himself was a larger-than-life lover of women, tender and involved but also voracious and incapable of fidelity, making his journals and notebooks, part of which Truffaut helped see through the press, read like a kind of amorous adventure story. His affection for Duchamp—as Beatrice Wood reported—was profound, and he often presented his friend in a heroic light; in his memoir he recalled that during his first years in New York the artist "could have had his choice of heiresses, but he preferred to play chess and live on the proceeds of the exclusive French lessons he gave for two dollars an hour." Although Roché probably intended only to highlight Marcel's bachelor independence, the examples of Hazel and Lydie suggest that Duchamp's preference for chess could sometimes be an alternative to something more—or less—than marriage.

Later in the same memoir, Roché added: "Some day someone will have to write a romantic essay on the subject of 'Marcel Duchamp and Women.' Judging by the adjectives he employed in his notes for the Bride Motor, he must relish them. He lets none into his confidence, but he does spoil them systematically with his fantasies."[16] It is an exceedingly odd comment: given the presence in Roché's diaries of incidents like the orgy in July 1924, why should he need to offer the notes to the Large Glass as evidence for Duchamp's love of women? And the last phrases suggest that Roché understood both the distance at which Duchamp kept women and the importance of fantasy in his relations with them. In his account of Duchamp's night with the three women he quotes his friend as saying, "There were moments when I didn't know where I was, when all three were occupied with me at the same time"—as if what Roché sought to arrange was an experience of disorientation that would mirror Duchamp's image of the single bride receiving the attention of the multiple bachelors. Roché's larger-than-life view of his friend is suggested by the title he gave to the novel he never finished about him, Victor , the name he invented on their very first evening together (he then punningly altered it to "Totor"). One day in 1924, while Duchamp was in Brussels on a chess trip, Roché interviewed both Yvonne Fressingeas (whose lover he also seems to

have been) and another woman with whom Duchamp was involved so that he could write about their feelings for Marcel in his journal. It is not impossible that he colored or enlarged Duchamp's image even in his diaries, perhaps projecting onto him some of his own more direct and uncomplicated sexual feelings.[17]

Duchamp had two long-term relationships with women, his liaison with Mary Reynolds that began in the 1920s (she was the second woman Roché interviewed in 1924) and lasted off and on until her death in 1950, and his second marriage, which lasted from 1954 to the end of his life. Reynolds was a remarkable figure among the American expatriates who lived in Paris between the wars. Striking and serene (as Roché described her), she was a former dancer who became an art collector and patron as well as a notable bookbinder; she was also adventurous and courageous, and remained in France to become part of the French resistance against the Germans during World War II. Her liaison with Duchamp seems to have begun in the spring of 1924, but for some time things did not go smoothly. Although the two were often together, Duchamp seems at one point to have demanded that their relationship remain secret, even to the point of forbidding her to speak to him at the Café du Dôme, where both went in the evenings. Roché reported that she was hurt by Duchamp's insistence on continuing to see what she described as "very common" women, and that she believed him to be incapable of loving. At least once during the early stages Duchamp seems to have wanted to break off the affair, and later—apparently around the time when Duchamp's first marriage was nearing its end—Man Ray described Reynolds as made so desperate by her relations with Duchamp that she was driven to drink.[18]

According to Roché's account in his unfinished novel, Victor , what made things so painful for her was Duchamp's desire to be her lover while rejecting any sort of fidelity—not just refusing it himself, but encouraging her to be unfaithful too. In addition, Marcel seemed to want to keep the relationship from becoming stable and predictable; although there were times when they lived together for months on end, Roché quotes her as saying that Duchamp preferred the periods when he only slept at her house once or twice a week. As time went by some kind of equilibrium set in; the two mingled their books and often va-

cationed together; all the same, Duchamp's desire to retain a measure of uncertainty remained. As he summarized the connection in his interview with Pierre Cabanne, "I went to see her often. But I had my hotel room. It was a true liaison, over many, many years, and very agreeable, but we weren't glued together in the 'married' sense of the word."[19] Even if its physical side was more or less ordinary, however, or sometimes so, the affair was one in which desire was aroused and managed in such a way that it was often denied a stable resting place. Duchamp's comment that the two were "never glued together in the 'married' sense," while seeming to describe only some sort of independence, might even mean—particularly in the mouth of someone so sensitive to the literal meaning of words—that it was the physical side of their connection with each other that was somehow uncertain or incomplete.

In 1954, at the age of sixty-seven, Duchamp took as his second wife Alexina Sattler—called Teeney—a widow whose first husband had been Pierre Matisse, a New York gallery owner and son of the famous painter. The marriage seems to have been calm and happy. Duchamp had good relations with his wife's three grown children, and one of them, Paul Matisse, became involved with his work, editing the surviving notes for the Large Glass that Duchamp had not included in any of his three published "boxes."[20]

In his interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp explained his willingness to marry at this late stage on the grounds that his wife was too old to have more children (she was forty-seven), the outcome he had sought to avoid by not marrying before. The implication was that the couple could have sex without worrying about offspring, but something more mysterious is suggested by the gift Duchamp gave his wife when they married in January 1954. It was a small sculpture (just over two inches high), called Chastity Wedge (Coin de chasteté; Chastity Corner is another possible rendering), consisting of two interlocked pieces of plastic, one in the shape of a wedge, its edge inserted so that it fills up the slit-like opening of the other, a rounded block of material of a flesh-like color and texture (Fig. 62). The title confirms that the space stopped up by the wedge is the opening of the female genitalia, making it impossible for anything else to find entry there; later Duchamp re-

Figure 62.

Duchamp, Chastity Wedge (1954)

ported that the couple kept it displayed on a table and that, when they traveled, "we usually take it with us, like a wedding ring."[21] Certainly it suggests a preoccupation with sex, but somehow blocked rather than freely engaged in; whatever else, it is hard to read it as the emblem of a couple with an ordinary sex life.

In the years before he made Chastity Wedge , Duchamp produced two other "erotic" objects, and they too seem to derive fascination from sexual uncertainty. One, Objet dard (the title combining in pun Dart Object and Objet d'art ) is certainly phallic, but the penis it offers is limp (Fig. 63); we might read it as invoking the same post-coital condition that seems to be called up by the drawing Le Bec Auer , but by itself the state it represents could be impotence just as well as satisfaction, suggesting even an inability to distinguish between the two. More complicated is Female Fig Leaf (Fig. 64), apparently produced by using the prone figure of Given as a mold. The resulting plaster object is certainly a reference to female anatomy, but is the protruding lip the reverse of

Figure 63.

Duchamp, Objet dard (1951)

Figure 64.

Duchamp, Female Fig Leaf (1950)

the vaginal slit, or a clitoris? Here fascination with sexual anatomy seems inseparable from the need to cover it with uncertainty and mystery.

These objects recall the strange—some would say shocking—picture he made around 1946 for a woman with whom he had some sort of relationship during and after World War II, Maria Martins. The wife of a Brazilian diplomat and herself a sculptor who moved in surrealist circles in New York, Maria Martins may have been the first model for the nude figure in the interior of Given . The picture Duchamp made for her in 1946 was an abstract landscape of sorts, or as its title, Paysage fautif , translates, a faulty or offending landscape. The title seems to hint at what analysis confirmed only at the end of the 1980s, that the viscous material fixed to the picture surface vaguely suggesting a kind of natural scene is seminal fluid, doubtless Duchamp's own. One might see the work as intended above all to poke fun at art, and especially at those who give it some kind of sacred status. But the picture is also, like many others, a kind of self-portrait, the readymade image of Duchamp as a lover of sorts, but a lover who makes his link to the woman on his mind, and creates an image of himself to send her, through masturbation.[22]

Despite the occasional flamboyance and intensity of Duchamp's sexual life, the pieces of evidence we have about it leave an impression of strange uncertainty, even of mystery, a result which must have pleased him. In 1921, writing to his sister and brother-in-law Suzanne and Jean Crotti to say that he would not participate in a dada show they were helping to organize, he explained: "You know very well that I have nothing to show—and that to me the word show sounds like the word marry."[23]Exposer does sound close to épouser in French, but the pun did not stop at the apparently intended implication that not showing work in public preserved his independence in the same way as bachelorhood; behind it lurked the possible admission that—at least at this still relatively young stage—he feared marriage as an exposure (exposer means that too) of something that his life of privacy and independence kept hidden. What might it have been?

Several possibilities deserve to be considered, even if we finally discard them. One is that Duchamp sometimes—or in some circum-

stances—experienced physical impotence, a condition that would correspond to the "deadness" Beatrice Wood spoke about, while also casting a certain light on the strange symbolism of Chastity Wedge, Objet dard , and Paysage fautif . The hypothesis of impotence need not be abandoned simply because Duchamp once fathered a child (if indeed he did); the case of men impotent in some situations or with some kinds of partners, but capable of normal sexual functioning at other times, is far from rare, and Freud even wrote an essay about the subject in 1912.[24] In Freud's view, such people suffer from psychic conflicts that require them to seek sexual satisfaction from women they cannot love in a fully emotional way, thus often from prostitutes or women like the "very common" ones with whom Mary Reynolds complained about having to share Duchamp, or from people like Yvonne Fressingeas (nominally a typist but probably some sort of prostitute) and her two friends, whom Roché may well have paid for their participation in the 1924 orgy. If Duchamp did sometimes experience impotence, however, there is little to suggest that the condition ever troubled him or made him unhappy; on the contrary, his repeated assurance that "cela n'a pas d'importance" and Beatrice Wood's image of his guru-like calm testify to the contented indifference with which he apparently faced sexual life. It seems unlikely, moreover, that an impotent person who valued his own mental powers would have spoken about grasping things with the mind "in the same way the penis is grasped by the vagina."

A second possibility is that Duchamp was secretly bisexual, or even a homosexual who sometimes tried to deny his attraction to men by seeking relationships—at least some of which were in the end unsatisfying—with women. This suggestion might find support in his assumed identity as Rrose Sélavy and the occasions it afforded him to dress and be photographed in female clothing. At a surrealist exhibition in Paris in 1938 where each of the exhibitors was represented by a mannequin, Duchamp chose to place his own jacket and shirt on a female figure naked from the belly down. (A light bulb in her breast pocket completed the outfit.) Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia spoke about his way of fabricating a personality "disengaged from the normal contingencies of human life" together with "his attitude of abdicating everything, even himself," as "part of the attraction he exerted on men and women

alike."[25] When Ettie Stettheimer wrote to Alfred Stieglitz about Duchamp's first marriage, she declared, in the midst of her disappointment, that she was "somewhat relieved nevertheless and that will tell you a little how I feel about him," to which Stieglitz replied: "At any rate it's a woman he married."[26] If one were trying to build up a case that Duchamp felt discomfort and hostility toward women as sexual beings, the hairless and prone figure of Given , on which he worked in secret for two decades, might be offered in evidence (although I have tried to suggest the limits to such a reading above), and Chastity Wedge , too. As for the large presence occupied by female bodies in his work, he would not be the first artist or writer to hide homosexual passions behind descriptions of ostensibly heterosexual involvements-one need think no further than Marcel Proust and "Albertine." No clues point to the identity of any possible male lovers, but Duchamp spent much time in chess clubs, out of sight of those who knew about his artistic life, and it is conceivable that he found sexual partners there. Yet if Duchamp was a closeted gay, the secret was very well kept; the few hints cited above—if they even count as such—seem the only intimations that this may have been the key to the mystery. Other well-known French cultural figures of the time who were homosexual thought it necessary to cast a veil over their orientation for propriety's sake, but they could not avoid, nor were they harmed by, having a certain number of people know the truth, as the examples of both Proust and Roussel attest.

Both these hypotheses come up against the additional objection that each would be hard pressed to account for the central place Duchamp's work gives to disillusionment as a consequence of sexual possession, and its celebration of desire without fulfillment. An impotent male would seem more likely to experience sexuality as frustrating at the moment he attempts to engage in intercourse than to regret satisfaction itself. A secret homosexual may face the problem of not desiring the objects others expect him to, but this would not account for the feelings described in the note on shop windows, where there is no reason to regard the items displayed as gendered. It might be suggested that disapproval and repression had buried Duchamp's real sexual impulses so deeply that he could not recognize them himself, but could a person

whose psychic economy was structured around keeping homosexual feelings out of consciousness have turned himself into Rrose Sélavy?

A third possibility is the one Beatrice Wood suspected: that he may have "suffered an unspeakable trauma in his youth." Perhaps his bland confession to Robert Lebel, that he had been hurt by his mother's indifference before he learned to develop a similar protective façade himself, veiled a more painful experience, to which he did not want to allude publicly or which he could not even wholly remember, although some residue of it may have surfaced in the 1912 dream of the bride turned into a great beetle and torturing him. Some practicing psychotherapists with whom I have discussed Duchamp's career suggest that if we combine the retreat into indifference and "deadness" reported by Beatrice Wood with the sense of female sexuality that Given conveys—invested with mixed elements of suffering and threat and imposed on the viewer as a moment of surprise and shock—the compound points to some sort of Freudian "primal scene," a traumatic infantile experience of sexuality either inflicted by some older person or observed and misperceived as violence.[27] That such an event may have occurred is certainly possible, but what makes it doubtful, in addition to the lack of any biographical evidence to support it, is that it would seem to point to a Duchamp more psychically troubled than most of the evidence of his life suggests. However unnerved by his sexual conduct some of his women friends may have been, for him his intimate relationships seem to have been sources of pleasure; nor did he ever seem to have difficulty in forming warm friendships with both men and women.

From a psychoanalytic viewpoint one other possibility can be suggested, and it returns us to the question of his relations with his sister Suzanne. It seems that one source of uncertain sexual identity in adults is having identified closely with a person of the other sex in childhood, a situation that arises with some regularity in the case of boy-girl twins, and a number of psychoanalytic writers report that a similar tendency to sexual confusion occurs as well in siblings near in age who were raised together in a twin-like configuration. Marcel and Suzanne, playmates and confidantes, and separated from the other siblings, seem to fit this pattern (as, by the way, does Raymond Roussel, also a person whose sexuality was not ordinary, and one in whom Duchamp found

much sympathetic fascination).[28] Some residue of such an early and powerful identification with femininity might help to understand why Duchamp was drawn to the identity of Rrose Sélavy and why he could envision a doubly gendered Mona Lisa blossoming out of her desire. It would seem to fit the central themes of his work with less trouble than either impotence or homosexuality. Combined in some way with the indifference he remembered in his mother, it might be made to account for the conjunction of a ready flow of erotic energy and a deferral of satisfaction and commitment that characterized many of his relations with women, and the reflection of this complex in his work.

But this remains just a hypothesis. Even if it could be pronounced true, we would still be hard put to distinguish between the ways that such childhood experiences may have continued to control and limit Duchamp's thinking and behavior and the ways that they became material for his conscious imaginative elaborations. The only thing it seems possible to say with certainty about Duchamp's sexuality is that the erotic themes that recur in his work do seem to reflect visible patterns in his life. The realm of sexuality provides good reason to reject the claims sometimes made about him, that his art was impersonal and unconnected to his own feelings, impulses, or preferences. As other writers on Duchamp have also suggested, the Large Glass was in some way a self-portrait, labeled as such by the reference to his own name in the first syllables of mariée and célibataires ; in another place he referred to it (even while denying that his art was one of self-expression) as "a little game between 'I' and 'me.'"[29] As an image of himself, the Glass portrayed more than one thing; on one level it was a picture of his deep ambivalence about communication, his desire to be at once present to others and absent from them. But this same two-sidedness is exactly what we find in the form of sexuality that combines an intense flow of erotic feeling with one or another form of withdrawal or "delay." Duchamp's resistance to permanent attachments was rooted more deeply than he made it seem by equating it with preference for a life free of responsibility; it arose out of the more radical need to give positive meaning to a pattern that recurred in many areas of his life. Finding pleasure in detachment was the general and underlying project that also found specific and visible expression in his attempts to undermine

habit, taste, and personal style, and in the trajectory that led through the readymades to the abandonment of painting.

Duchamp did his final painting on canvas, Tu m ', in 1918 (the last previous one was finished in 1912), and stopped working on the Large Glass five years later. Afterward he gave many explanations for why he no longer made pictures, sometimes teasingly hinting at the surprise he would deliver with Given by denying that he ever took a specific decision to stop, and insisting that nothing would prevent him from going back to work if ever he felt the urge.[30] But he often admitted that his interest in painting had never been wholehearted and that he seldom felt altogether comfortable doing it. In 1957 he recalled that he had felt "disgusted with the cuisine of painting" even as a student, adding that even though he did it "diligently and with pleasure" for a number of years, his underlying urge was never great and he found the work itself slow and sometimes painful. "I never had the enthusiasm of the professional painter; with me it was the idea that counted more."[31]

By privileging "the idea" in this way, Duchamp seems to have meant two things: first, that his paintings were inspired by ideas, like the philosophical notions or speculations connected with the Large Glass; and second, that what interested him was the idea of being a painter rather than the actuality of making pictures. In the first regard, he once explained his turn away from making visual images on the grounds that he preferred to keep his ideas inside his head: "I have not stopped painting. Every picture has to exist in the mind before it is put on canvas, and it always loses something when it is turned into paint. I prefer to see my pictures without that muddying."[32] In the second he recalled that his reasons for becoming a painter were like those of many other young people in search of a kind of life that avoided taking on ordinary responsibilities: "One is a painter because one wants so-called freedom. One doesn't want to go to the office every morning."[33] Each of these ways of preferring the idea of painting to the execution deserves to be considered on its own. We will look into the first in this chapter, and the second in the next.

One way to see what the first means is to compare Duchamp's words with something his contemporary, the poet Paul Valéry, said about po-

etry: "The greatness of poets is to grasp with their words things that they could only weakly glimpse in their minds."[34] Valéry was profoundly a man of ideas, at least as much so as Duchamp, but he had a different notion of how mental contents were related to artistic expression. In his view art was a mode of thinking, and the material means an artist used—words for a poet, colors and shapes for a painter—were media through which the mind could achieve forms of understanding unattainable without them. Duchamp recognized that aspect of painting too—at least he seemed to for a time—when he sought to explore ideas about motion and "the dissolution of form" in some of his early works. But his later notion that the ideas a painter puts into his work already exist full-blown in the mind, so that giving them painted form amounts to "muddying" them, takes away from art whatever special powers it possesses to grasp experience in ways different from some kind of inner and immediate intuition. Assigning ideas wholly to an enclosed, immaterial space implies that human thought gains nothing from the forms into which it is cast by the various material means—words, images, sounds—that give to each art form its particular way of encountering the world.

Valéry—to stay with him for a moment—was equally aware that giving material expression to ideas had another side, one that threatened to corrupt or pervert them. He knew that language was conventional and replete with the survivals of discredited or discarded ways of thinking, and he often spoke about it in the same terms of anxiety and suspicion employed by Jules Laforgue. To these dangers he added the deeper peril that a writer, in the act of setting down thoughts, is likely to be turned aside from pursuing inner truth, whether knowingly or not, by the need to consider how a potential audience may react. So deeply troubled was Valéry by the fear that he would "lose his soul" by writing, sacrificing his intellectual liberty and purity to worries about what others might think, that he left his early verse unpublished and stopped producing any for a number of years, becoming one of Duchamp's predecessors in the self-conscious abandonment of art.

Valéry found a way out of this crisis; it led through the recognition that the unalloyed purity of self he sought to preserve from being corrupted by language was at best an ideal, at worst an illusion, rooted in

the ability consciousness possesses to objectify every element of experience and thus to imagine its own independence of everything outside the mind. Any person who actually seeks to live at such a distance ends up in a void, cut off from life itself; the only escape is a return to the external world of ordinary existence, and to the language that is imprinted with it. Every person, and especially every writer, was thus a complex mixture of two selves, one "pure" in its ability to conceive itself apart from the conditions of its own life, able to call even its own personality into the court of consciousness and to condemn it, the other finite and particular, attached to everything that makes a given person what he or she actually is—and can only exist by being—in real life. The dilemma of being human, and of trying to be an artist, lay in the Janus-faced recognition that these two ways of being were deeply at odds and yet each needed the other, each remained incomplete without the other. The core of creative activity was a neverending dialectic of self-making, in contrast to Mallarmé's search for a perfect work that would dissolve the mere individuality of its author; what made works of art meaningful was their witness to some person's momentary struggle, successful in the best cases, to effect a mutually nourishing encounter between the internal and external facets of experience and selfhood.[35]

Duchamp's words and actions testify to a different sense of self, with a different orientation to the world. According to the note on shop windows, to yield to the temptation to find satisfaction in the objects that beckon from the other side of the glass is to fall into disillusionment, and the drama of desire perpetuated in the theater of the Large Glass enacts an image of a self that grows and expands only when nurtured by the contents of its own imagination. The notion that ideas are merely "muddled" by the attempt to give them material form in paint describes the process of art making in a precisely parallel way, equally positing that the self can be free only as long as it avoids attachment to outside objects and that it can find sustenance only in the images of them it carries within. Duchamp's stance was like the one ruling Valéry's mind at the time he abandoned writing for the public, but whereas Valéry criticized and then altered his original desire for purity and dis-

tance, Duchamp made this desire more and more the principle of his life and the content of his work.

In this perspective, Duchamp's readymades take on a different set of meanings from the ones usually attached to them. An object removed from its context of use may be shifted to an environment where its aesthetic qualities gain independence and relief, but a prior displacement operates first, allowing the person who seizes on it in this way to employ it as an instrument for achieving distance from the world in place of involvement in it. Duchamp began his assemblage of objects—not yet seen by him as "art" but already fulfilling this other, more primary function—at the time he was withdrawing from artistic activity and social life, following his return from Munich. By collecting them in his studio, Duchamp made his bicycle wheel and bottle rack first of all signs of his ability to appropriate objects without being subjected to the conditions their ordinary use imposed—on travel or exercise in the one case, on obtaining wine or cider in the other. The objects might provoke ideas or desires, but these remained within Duchamp's closed mental world.

As art objects, too—once they entered into that status—Duchamp's readymades were able to satisfy his need for giving immediate, intuitive expression to his ideas without the "muddying" he feared the act of painting would bring. Making a representation of something, whether verbal or visual, can often be a difficult and drawn-out process, requiring erasures, revisions, abandonments, startings-over—as Duchamp said of his own painterly practice during the years when he was still occupied with it. With a readymade, by contrast, the artist achieves a relationship of complete mastery and possession all at once, absorbing an object into a universe of consciousness without ever experiencing the resistance of the material world. The use Duchamp made of his bicycle wheel and bottle rack transformed them instantaneously into metaphorical signifiers. With such means, the artist's power to represent his ideas becomes immediate and unrestricted.

Although this way of understanding Duchamp's readymades has usually been hidden by the standard images of him as the great rebel against art and dissolver of personal coherence, a somewhat similar

view was proposed in 1965 by three artists in search of a radical escape from the Western humanist tradition, which, they believed, devalued nature in order to justify subjecting it to human order and control. Duchamp, they found, offered no support to their project of giving dignity and independence back to the nonhuman world, because just where he had seemed to undermine the premises of humanism he had in fact strengthened them.

Marcel Duchamp's brusk rupture with oil painting was, in reality, accompanied by no reversal of perspective. The move from the cubist object, entirely constructed by the constitutive act of the painter, to the manufactured object merely touched from a distance by a signature, entails no transcendence of the traditionally demiurgic notion of the "creative act." How could [Louis] Aragon have seen in this attack on pictorial practice and the idea of the person as a maker "the indictment that puts the personality on trial?" If one wants art to cease being an individual matter, it is better to work without signing than to sign without working. How can people not have understood that to prefer the personality that chooses over the personality that makes things is just to take another step in the exaltation of the omnipotence and ideality of the creative act? It is the final arrival at a magical liberty, at absolute subjectivism: whatever the thing, its meaning is only what man gives to it.[36]

The writers of this comment recognized the power Duchamp was claiming over objects by making them readymades, even without being aware that in turning to them he drew them into a private universe of symbolic meanings. They also understood that behind Duchamp's claim to have devoted his career to destabilizing his personality, countering the pull of taste and habit with an aesthetic of indifference and avoiding the trap of fixed identity by his various strategies of selfcontradiction, there lurked an uncompromising exaltation of the self. All Duchamp's modes of seemingly undermining his own coherence as a consciousness were actually ways to assure his detachment from things that might draw him into conditions or relations he could not

control; they freed him to live wholly in the world his imagination projected.

The universally accepted image of Duchamp as the hero of anti-art also takes on some different features when placed in this light. From the time he created the category of readymades in New York, and especially after the scandal of Fountain , Duchamp was often viewed, and often presented himself, as a destroyer of traditional artistic practice. But as we have seen, this was not Duchamp's original intention when he took over his first objects as "distractions." By giving the readymades new public status as weapons in the war against art, Duchamp cast a veil over their original role as elements in a private universe of meaning. Becoming the knight-errant of anti-art masked him against recognition as the person who had given totally free reign to the subjectivist impulse to enclose art in the unenterable space of its maker's consciousness, the possibility Gleizes and Metzinger had identified and warned against in On Cubism .

One celebrated aspect of Duchamp's career suggests he continued to value the retreat into privacy at least as much as the public challenge that grew out of it: from the mid-1920s he devoted much of the time others expected him to give to art making to playing chess. The image of Duchamp as the artist who abandoned art for chess added to his mystery and fascination, and many people have speculated about why he did it. No full answer can be given, and we ought not to underestimate the simple circumstance that he was really quite good at it, competing on the French international chess team for a number of years, gaining reputation as a player, and even writing a book and for a while a regular newspaper column about the game. Moreover, chess had long been one of his passions, shared by other members of his family and serving as one of his artistic subjects almost from the start. His early pictures show that the links between chess and art he described in later comments and interviews had been present to his mind in some way all along.

But for the young Duchamp to play chess was not the same as for the painter of Nude Descending a Staircase or the instigator of Fountain to devote himself to it. Chess was a pursuit that could never issue in

the kind of public confrontation for which Duchamp was famous by 1920; like vanguard art, it appears to outsiders as an enclosed, private realm, peopled by enthusiasts who alone understand its intricate mysteries, but unlike the art world it contains no potential to make public scandal. Duchamp did not flee scandal, any more than fame, but he had not really set out seeking it either. After his return from Munich he had withdrawn into a more private life, employed as a librarian and contemplating a project—the Large Glass—that could be expected to keep him out of sight and in his studio for a long time. The news of his success at the Armory Show had drawn him out of this quietude, and it is not hard to see the turn to chess as a kind of reentry into it, even as another of those periodic journeys into some more private and protected space that Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia had noted in him before the war. Duchamp's aggressions were impossible without his withdrawals, as the birth of Given would demonstrate for the last time.

In addition, chess had a recurring relationship to Duchamp's strange amorous history, playing a role in the fiasco of his first marriage, and recognized by both Man Ray and Henri-Pierre Roché as his way of avoiding involvement with women whose desires he aroused. As an alternative to making both art and love, chess filled the space in Duchamp's life left vacant by his equation of épouser with exposer , providing a way to interact with other people and to manipulate symbols while shielding him from both kinds of self-revelation. During the intense flurry of painterly activity leading up to his trip to Munich, Duchamp had used chess as a way to approach questions about the outside world, constructing a meditation on various forms of human relationships in The Chess Game of 1910 and using chess symbols as elements for exploring the dissolution of form in the "king and queen" pictures of 1912. Later, however, chess became one of his ways to substitute purely mental forms and images for actual objects of experience, as he wrote to Louise and Walter Arensberg in 1919: "I feel altogether ready to become the chess maniac—everything around me takes the form of the knight or the queen, and the outside world has no other interest for me than its transposition into winning or losing positions." Chess, in other words, drew Duchamp so powerfully because it was a way to

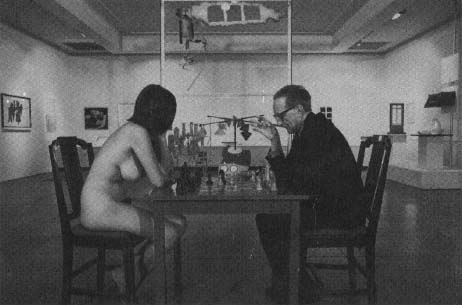

Figure 65.

Julian Wasser, photograph of Marcel Duchamp and Eve Babitz playing chess at the

Pasadena Art Museum (1963)

live in a universe where symbolic equivalents replaced objects instead of referring to them. Explaining his fascination for the game to Pierre Cabanne, he insisted that in it "there is no social purpose. That alone is important." He liked living among chess players because they "are completely cloudy, completely blind, wearing blinkers. Madmen of a certain quality, the way the artist is supposed to be, and isn't in general."[37]

These comments provide the perspective from which to understand why he was so charmed in 1963 when one of the organizers of the first major retrospective of his work, at the Pasadena Art Museum, staged a picture of him, fully clothed, playing chess with a totally nude woman. In the photograph (Fig. 65), Duchamp points toward the woman with two fingers of one hand, but his eyes are firmly fixed on the chessboard before him. She may arouse desire in him, but his interest in her has been displaced onto the elements of the game, and her presence only serves to underline his cloudy and blinkered absorption in its separate

universe. To make the point more clear, they sit before a reproduction of the Large Glass, icon of the power of perpetuated but unfulfilled desire.[38]

Certain features of chess make it an excellent stand-in for Duchamp's own aesthetic attitudes and ideas. Chess pieces are symbols for social identities—king, queen, bishop, knight, pawns—which the players manipulate in ways that resemble the assemblage of words into sentences in a language. But the appearance of reference to a world outside the chessboard is false, each piece possessing powers that may vaguely echo those of its worldly counterpart but which in fact belong only to the marked-off space of interaction defined by the board and the rules; hence the language of chess possesses from the start the character of apparent reference transformed into self-reflection that Duchamp sought to give to verbal language in The and Rendezvous of Sunday, February 6, 1916 . Moreover, in French the word échecs contains the associated connotation of "checks" that appears in the game but is absent from its English name, hence it creates a pun on "failures" or "restraints," exactly the conditions Duchamp sought to impose on ordinary linguistic reference by his language games (and whose sexual counterpart he depicted in Chastity Wedge ). Chess pieces resemble a language whose journey to signification is perpetually "checked," a symbolic system perfectly enclosed in the space Duchamp called "delay."

In 1932 Duchamp wrote a brief book about chess, collaborating with a rather well-known expert, Vitaly Halberstadt. As one with a very elementary knowledge of the game, I have not tried to read this book, but it deals with a rare and obscure problem of the endgame that arises in certain configurations where only the two kings and a few blocked pawns remain. In this situation, a winning strategy requires that one king choose its moves with respect to the colors of the squares occupied by the other. According to one expert player who knew Duchamp, the reasons for this necessity are quite mysterious, so that the solution proposed in the book establishes a "relationship between squares that have no apparent connection," a kind of telepathy between the squares. Such a description is bound to call up echoes of the strange communication between the bride and the bachelors; moreover, one of the things that gave Duchamp pleasure in explaining this (along with the

conviction of having solved a difficult and obscure problem) was that "even the chess champions don't read the book, since the problem it poses really only comes up once in a lifetime."[39] Issuing the book, in other words, was a way of simultaneously entering the public realm and remaining in an obscure place where no one would notice him, fulfilling his sense of chess as a place where one lived with ideas that meant nothing to anyone else.

In 1952 he spoke about chess to the annual banquet of the New York State Chess Association, giving an account with multiple echoes of his own practices. A chess game "looks very much like a pen-and-ink drawing, with the difference, however, that the chess player paints with black and white forms already prepared instead of inventing forms as does the artist"—hence it was an art of readymades. Although the design formed by the pieces seems to have "no visual aesthetic value," the reason it appears to lack beauty is only that its form "is closer to beauty in poetry; the chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chessboard, express their beauty abstractly , like a poem." This meant that the aesthetics of chess had its source in "imagination, inventiveness," which the players use in putting pieces into what each hopes will be a winning combination; but there is "a real visual pleasure" in the "beautifully elaborated combinations and conceptions" that a series of moves turns into "an ideographic story." Hence Duchamp could condude "that every chess player experiences a mixture of two aesthetic pleasures, first the abstract image akin to the poetic idea in writing, second the sensuous pleasure of the ideographic execution of that image on the chessboard." Chess, then, was a visual art with intellectual and literary roots, the images acquiring beauty through their association with ideas rather than by virtue of their formal qualities; the sensuous pleasure comes from being able to see ideas in visual form, resembling the enjoyment he said he found in contemplating his Glass, when he described it as an amas d'idées . For Duchamp, playing chess was one more way to paint a portrait of himself as man and artist.[40]

These, however, are Duchamp's views, and the light in which they make chess appear is not the only one in which to consider it. Looking at chess from a different perspective one might notice first of all that

unlike art—at least modern art—it is a realm where the rules never change; despite all the imagination and inventiveness players may bring to bear on it, the game retains its classic stability, providing an enduring framework of interaction.[41] The only way to demonstrate originality is by agreeing to remain within the rules, and success depends on the agility and imagination with which a player who accepts the limitations of existing social roles—as defined by the moves allowed to the individual pieces—can still discover new possibilities in their combination. (Such originality was just what Jules Laforgue refused to acknowledge when he denied that people could attain genuine selfhood as long as they had to assume roles others had played before them.) Nor can the conception behind a winning game remain hidden once it has achieved victory; what is on one player's mind may be obscure to the other one for a while, but in the end each has a chance to read the other's moves as a revelation of his thinking and strategy. In this light chess takes on the features of a much more traditional notion of art than Duchamp's, and of a more integrated and conventional model of social life.

How much Duchamp may also have been drawn to this second way of experiencing chess we can never be certain. Some aspects of it—notably the formal stability and permanence—seem to have been in his mind in 1912, if, as suggested above, he was using the king and queen to stand for durable and unchanging forms against the forces of decomposition represented by "swift" or "high speed" nudes. It may be that on some level Duchamp's later turn to chess revived this appreciation of its formal stability, as a respite from the spirit of boundless fluidity he helped to introduce into the art world, and that he valued the clarity that the game finally established between two minds, all the more because his work set up so many barriers to communication. But there is no way to know for sure, and such attitudes would have brought him toward an orientation of which one finds few signs elsewhere in his life. Even if the turn to chess in some way signaled a desire for stability and communication, his own comments about the game indicate that he saw it above all as a continuation of the same determination to inhabit a purified and hermetic mental world that was dramatized in the Large Glass and enacted in the turn to readymades. What the other, non-Duchampian view of chess points to are similarly non-

Duchampian views of art and life, ones which recognize that the acceptance of limitations is the condition for playing any social game and which posit communication and interaction as the final aims of aesthetic activity. These alternatives remain, as Duchamp always knew they would, the stable backdrop that makes his rebellions visible; without them his escapes and challenges would lose their meaning.