"The Key to Her Heart":

Music in a Life

The arts always held a proud place in the life of Isabella Stewart Gardner. As a girl and young woman in New York City, she was privately educated (attending the Miss Okill School) and acquired fair skill at sketching and watercolor. Her biographer Louise Hall Tharp informs us, although without documenting the claim, that young Isabella also learned to read music well. Presumably, this means "well" by nonmusician standards—that is, she may have been able to follow a score, more or less, and play simple pieces, or at least pick out melodies and chords, at the piano. (As a grown woman, Gardner rarely drew, however, and never played an instrument.) Clearly, her appreciation of the arts was keen and her exposure to first-rate practitioners extensive, both in New York—not least at her family's church, Grace Episcopal Cathedral (the English composer George Loder was the distinguished organist and music director)—and in France and Italy, where at seventeen she was taken by her parents for more than a year of travel and additional schooling. If, as Tharp concludes, this exposure only made the young Isabella Stewart feel unsatisfied with her own amateur accomplishments, she was not alone: upper-class American women in the later nineteenth century were generally growing impatient with the traditional female role of providing modest entertainment at the keyboard for family and guests.[7]

Whatever the motivation, Gardner's musical passion found its primary outlet in concertgoing. After settling in Boston, she faithfully attended the concerts of the Harvard Musical Association (an important predecessor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra); whenever she returned to New York for a visit, she took in great quantities of music and theater.[8] In addition, the Gardners' passion for world travel brought them into contact with some distinctive musical experiences, which Isabella vividly reported in letters and diaries. Thailand: a priest, overheard chanting by moonlight. Java: a court reception at which "a large orchestra [i.e., gamelan] in the shadow . . . played most strange music and with a strange fascination. The whole thing under one's breath, and as if something were going to happen." Egypt: a muezzin; dervishes dancing to a darabukka drum; music of shepherd pipes coming "to us from all the hillsides"; and—at an American Mission School—boys singing a familiar Protestant hymn in Arabic, which, Gardner noted, "startled and affected me." Venice: music in a Hungarian-style café, and a moonlight ride through the lagoon in Guillermo's "music boat" to the sounds of "a delightful ser-

enade" (as Jack described it to a friend). Vienna: waltzes conducted by Eduard Strauss in the Volksgarten. Berlin: the Joachim Quartet. Paris: Jules Massenet, who played his new opera La Navarraise to Isabella at the piano.[9]

By the 1880s Isabella and Jack had become pilgrims to the Wagner Festival at Bayreuth (they went together four times, and she went one other time without Jack), were spending every other summer in Venice, were hobnobbing with the rich and famous (e.g., Princess Metternich), and were beginning to collect paintings, rare books, and manuscripts, as well as signed photos of notable opera singers and other musicians.[10] Both at home and abroad, they were also attracting talented friends who were to remain faithful to them for life; among these were a number of major writers, artists, and scholars (Henry James, John Singer Sargent, Bernard Berenson), and musicians as well (including the composer-pianist Clayton Johns and Wilhelm Gericke, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra). In 1880 the Gardners acquired a house that adjoined their Beacon Street home and, by knocking down several walls, created a first-floor music room big enough for concerts by chamber ensembles or even a medium-sized orchestra, although the space was by no means as big or high-ceilinged as the Music Room in the future Fenway Court.[11]

How much Jack Gardner himself cared for music is a bit of a mystery. Tharp states that he was "well educated in music and sufficiently fond of it," but she claims repeatedly, and with a touch of ridicule, that he was less interested in music than his wife and that, in particular, he disliked Wagner. A careful examination of the evidence, though, reveals that Tharp has exaggerated the difference between the spouses in musical matters; in particular, Jack's supposed dislike of Wagner's music derives from Tharp's skewed reading of a single remark in a letter to Isabella from Gericke.[12]

But even allowing for errors and overstatements, Tharp's basic point remains perfectly plausible and even likely—namely, that Jack was less obsessively enamored of music and art than was La Donna Isabella (as friends called her). Indeed, one would be astonished had it been otherwise, given the extraordinary intensity of Gardner's artistic passions and the fact that the cultivation of the arts was at the time widely considered part of a society lady's domain and even responsibility, while her husband tended to business and financial matters.[13]

The more relevant question is not whether Jack always shared his wife's taste in music (or in paintings, poetry, or diamonds), but whether he encouraged, supported, and "indulged" his wife's tastes (as her first biographer, Morris Carter, who knew her well, put it).[14] The answer seems from the evidence to be an over-whelming "yes," even if, as has been suggested, he swallowed hard at some of her most extravagant purchases. His support, one suspects, derived in part from self-interest: the lavish parties, with splendid music, that Isabella organized surely helped confirm Jack's status among his peers, no less than did the $100,000 Titian (The Rape of Europa ) that hung in the drawing room of 152 Beacon Street.[15]

But Jack's support of her schemes and projects derived primarily from something deeper—namely, his devotion to her. He seems to have enjoyed the splash

and unpredictability—the sense of fun—that she brought into his predominantly practical and duty-bound life,[16] and he also seems to have understood her emotional needs. For one thing, her rejection by the Bostonian matrons during their first married years must have hurt Jack and certainly seems to have brought them closer together. Far worse, their adored child Jackie (John L. Gardner, Jr.) died in 1865 at the age of 20 months, and Isabella was subsequently informed that she could never again risk becoming pregnant.[17] Isabella plunged into a deep depression until Jack helped her find her bearings again by taking her to Europe (she was carried up the gangway on a mattress) for several revivifying months of touring, museums, and concerts in Scandinavia and Russia, Vienna, and Paris.[18]

From that point on—and they had three decades more together—Jack seems rarely to have flinched at the expense of time, effort, or cash that Isabella poured into the arts, nor indeed objected to her welcoming various handsome young male artists and musicians into her entourage (see, e.g., fig. 6). Whatever limits were imposed on their collecting and other artistic activities seem to have come from a mutual awareness that their financial resources were substantially slimmer than, say, those of Andrew Carnegie or the Vanderbilts.[19] Henry Lee Higginson, the founder of the Boston Symphony and one of Jack's closest friends, summed the situation up fairly in a letter to Mrs. Gardner years after Jack's death: "You conceived nobly and have lived beyond your conception—of beauty and duty. Clearly it was your dream, and Jack helped you as he could [my emphasis]. To our country full of life and enterprise what dream could have accomplished more?"[20]

The constraints on the Gardners' collecting habits were lifted a good bit in 1891, when Mrs. Gardner's father died, leaving her $1,600,000.[21] Some of the major works in the Gardner Museum were purchased in the next few years, including, significantly, a scene of domestic music-making: Vermeer's The Concert . During the mid 1890s, the Gardners also developed the idea of building a spacious new house-cum -museum. When Jack died in December 1898, Isabella—although 58 years old—carried out the plan, thanks in part to Jack's estate of $2,300,000 (his will trustingly permitted her to tap the principal).[22] She did her part as well, instituting economies in such areas as food and servants, even bragging at times about having to darn her own stockings.[23]

"Fenway Court," as she called the new structure, is a four-story palazzo (address: 2 Palace Road) but turned outside-in, as befits a northern climate: the outer walls have few windows; instead, carved stone balconies from a mansion in Venice, where they faced outward to the canals, open onto a central courtyard that was and still is filled with flowering plants year-round (fig. 7), thanks to a protective glass roof. The building was unveiled on New Year's Day 1903, in a memorable evening that included a concert—in the large "Music Room"—by fifty members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Gericke.

In the years that followed, Fenway Court, like Isabella's previous home, served as a meeting place for local musicians and a stopping point for visiting Europeans (e.g., Pablo Casals, Ferruccio Busoni, Vincent d'Indy).[24] Gardner had now become

Fig. 6.

In the gardens at "Green Hill," the Gardners' country home in

Brookline, Massachusetts, June 1903. From left: Richard Fisher,

Isabella Stewart Gardner, two unidentified young men,

and the tousle-headed pianist (and future New England

Conservatory professor) George Proctor. Isabella Stewart

Gardner Museum Archives, Boston.

a tantalizing, often veiled eminence (fig. 8). She opened the galleries and Music Room on selected occasions, including by-invitation-only social events and fundraising performances for charities but also a small number of serious concerts open to the general public; these latter included two full seasons of Kneisel Quartet concerts, 1908–10 (including the premiere of Arthur Foote's Second Piano Trio, Op. 65, with the composer at the keyboard), several seasons of concerts arranged by Julia Terry, a 1908 Walter Damrosch lecture on Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande (coordinated with the performances at the Boston Opera Company under André Caplet), and an early performance (by the Flonzaley Quartet) of the Schoenberg String Quartet No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 7.[25]

By 1914 Gardner, aged seventy-four, was losing interest in mammoth social gatherings and feeling the need for ever more wall space to display paintings and tapestries. The Music Room was therefore split horizontally to create new and separate upstairs and downstairs areas.[26] Solo recitals and chamber music thenceforth took place in the newly created second-floor Tapestry Room. (The tradition continues: recitals are given twice a week in the Gardner Museum today, in the same room.) Beginning in late 1919, when Gardner was partially paralyzed by a stroke, she particularly appreciated the musical ministrations of the violinist Charles Martin Loeffler, the pianist Heinrich Gebhard, and others (see Vignette D), and the piano recitals by students of her former "musical protégé" (as she her-

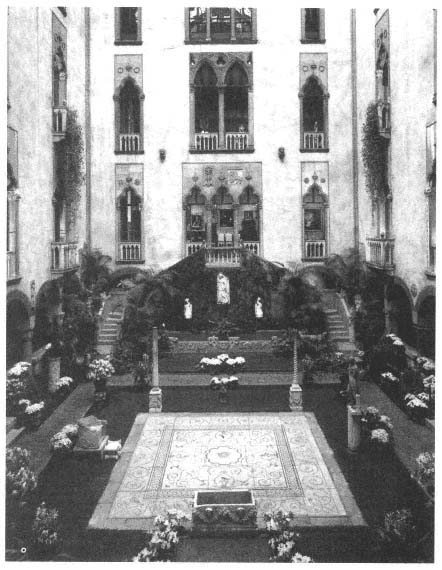

Fig. 7.

The glass-roofed courtyard at Fenway Court (built 1899–1902), including at

rear the stairs from which Dame Nellie Melba sang.

Photograph by Greg Heins, 1981; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Archives, Boston.

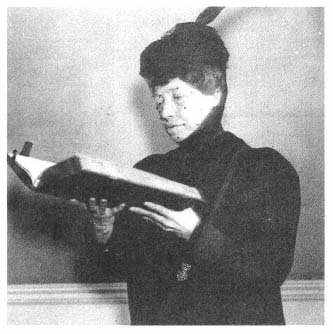

Fig. 8.

Isabella Stewart Gardner, lover of things old and rare, in 1907.

Photograph by O. Rosenheim, London, taken at the home

of Henry Yates Thompson; Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Archives, Boston.

self once put it), the New England Conservatory professor George Proctor.[27] At eighty-two, two years before her death, the bedridden Gardner reported to a correspondent: "I think my mind is all right and I live on it. . . . I really lead an interesting life. I have music, and both young and old friends. The appropriately old are too old—they seem to have given up the world. Not so I, and I even shove some of the young ones rather close."[28]