PART THREE—

THE REVISION OF THE MODERN

Chapter Five—

Architects and Creative Work

"You could not help getting [from Louis Kahn] this sense of hope that architecture was ultimately poetry and art, transcending accommodation, shelter, and program." This statement has the generality of a cliché. Yet Charles Gwathmey pronounced it with absolute conviction, and one can see it emanating from a man's serious involvement in his work. Less celebrated architects than Gwathmey also take it for granted that art and meaning make architecture more than mere building. Here is, for instance, the principal of a commercial firm with a three-generation history and a more recent one of making production drawings for many famous designers: "I think art has a lot to do with architecture. . . . What you want is a businessman who is willing to spend a little bit of money so the buildings you are designing have an ability to say something. We have a number of jobs that we think have a lot of art in them." The creation of meaning—"saying something"—still appears to be the distinctive quality of architecture, but it is implicitly quantified and made into a commodity. If "a lot of art" can go into a building, it is also possible to put in "a little" or none. One can only tell when it is "enough" by the money it costs.

The skeptic might see these two preceding statements as candor on the one hand and pretension on the other. Yet architects are wont to repeat (with variations) Gwathmey's notion that architecture must transcend the requirements of practice and therefore go beyond its conditions of existence. Joan Goody, for instance, treats architecture as the architect's secret

intention in a constrained process. She does not try to say what it is , except the undefined beauty that could not be quantified and is not paid for: "Architecture is the most valuable, the hardest to make of the things that we do. . . . They pay us to be sure they make it through the building inspectors and the zoning, that the clients will be happy, that they are rented . . . but the extra layer of beauty we have to sneak in." Because of general properties inherent in building, it is difficult to articulate what architecture is . Architects' occupational ideology forms around this difficulty.

As physical artifacts, buildings do more than articulate spaces within their shells: They also make the space around and between them perceptible and organized. As significant artifacts, buildings give spatial expression to the social relations and basic social hierarchies that inform a culture, nourishing its language and cosmology with spatial metaphors.[1] In this sense building is like music or poetry: It is impossible to fully describe in words what has been created, for our ability to describe depends on experiencing with our senses an artifact that has "feeling and form."

Each culture has its specific building arts, and in ours architecture is that which our architects do. In Western culture, architects profess to be specialists in transforming the complexity of buildings into beauty. Art critics and architectural historians specialize in telling us what that beauty consists of, but architects lay claim to its creation. Their claim implicitly rests on a syllogism characteristic of this profession: Architecture is an art. Only architects produce architecture. Architects are necessary to produce art.

The profession of architecture depends on clients, on executants, and on rival professions to whom it is often subordinate in the field of construction. This means that the profession of architecture is not autonomous but rather is fundamentally heteronomous. Yet architects "own" both the name and the discourse of architecture; the basic syllogism affirms and preserves the profession's identification with beautiful buildings. When noted designers grant interviews, the syllogism is tacitly taken for granted: The lay interviewer must identify architecture with what respondents do; otherwise no interviewer would be asking them about their work and their views.

While the syllogism of architecture establishes the profession's collective authorship of buildings, authorship for elite architects (the "gurus," as the press says) merges with charisma derived from the ideology of art. The syllogism and the authorship it claims are basic prerequisites of architectural ideology.

This ideology assumes that the art of architecture transcends the utilitarian and technical tasks of building. Beauty is what justifies a building's

permanence in time and its significance in history. Architects with an exalted conception of their work aspire to do something beyond the practical services that clients require. Directly, in their work, and indirectly, in what they say about it, they make rhetorical choices intended to prove architectural quality to their peers, their clients, themselves, and something undefined they call "the public"—in this order.

In this chapter I consider, first, how architects articulate the object of architecture (the thing to which they are committed) and the subject of architecture (their role as author). We should not expect them to penetrate what the critic Reyner Banham, borrowing an image from science, calls architecture's "classic 'black box,' recognised by its output though unknown in its contents."[2] Rather than the specific substance of architecture, their rhetorical constructions reveal different parameters and expressions of the occupational ideology.

The contours of this ideology become clearer in the second section, where I examine the orientations that architects have toward three ways of seeking transcendence in their work: by creating meaning for their buildings, by emphasizing the craft of architecture, and by highlighting the enhancement of life that architecture provides. Each represents for elite designers an attempt to transcend the narrow mandate of their work.

Architecture's Subject and Object

Architects talk about the art of architecture in four main ways: in general terms that do not tell us how it is different from other forms of building; in personal terms that focus on the frustrations of a misunderstood and threatened enterprise; in very specific terms that explain what they want to achieve in particular projects and how they go about it; and in prescriptive terms that offer specific critiques or variations on the theme "this is not architecture."

There is no theory of architecture or, as one historian writes, "none that has not been used to justify totally different styles of architecture over the past two centuries."[3] Peter Eisenman, the architect and cultural entrepreneur, thinks that architecture lacks "cultural power" because it lacks theoretical foundations. This implicitly explains why architects have difficulty imposing their syllogism, or, which is the same, their own distinction between architecture and building, on the public and potential clients. Comparing architecture to law and economics, Eisenman argues that architecture has always vacillated between extracting theory after the fact from realized projects and engaging in "ideological practice," which proceeds

from developed theory. The opposite of theory is, for him, the business of architecture; only theory can provide autonomous criteria for judging the results of practice: "In architecture, the theory is under-valued because it does not matter. . . . Everything is concerned with selling, with the media. We seem to have no corrective, no notion of what the discipline is against which to measure results."[4] Eisenman's argument implies that "the capacity to shape society as law and economics do" depends on the recognition of professional criteria by the state and by relevant others: "When the government wants a legal opinion it goes to the Harvard Law School or the Stanford Law School for advice. When there is a question of development or environmental concern, nobody goes to the architecture schools for advice."[5] Now, in the United States as in Europe, practicing architects (rather than academics) invariably sit on fine arts commissions, design review boards, and city planning committees, even if their advice is often ignored. Eisenman's point is that they are not taken seriously because their expertise does not rest on autonomous theory.

Eisenman's argument was part of an exchange with Henry Cobb, whose reply (as the senior partner in I. M. Pei's firm rather than the chair of the Department of Architecture at Harvard's Graduate School of Design, which he was at the time) is significant. Architecture, Cobb implies, must choose between doing anything and advancing as a purely theoretical form of knowledge. But the choice is already made: In order to exist, architecture needs realizations. Invoking the theoretical authority of an outsider, Cobb cites Michel Foucault: Architecture belongs among the composite practices (like the practice of government) that the Greeks called techne; it is "a practical rationality governed by a conscious goal."[6] Cobb then implicitly returns to the basic syllogism of architecture, suggesting that it is bound to fail: "Architecture by definition gives three-dimensional form to the society from which it springs, portraying it in a form so vivid and influential that it has the status of a cultural artifact; on the other hand, this cultural power does not invest architects or architecture with the kind of direct manipulative power that . . . lawyers and the law or economics and economists have in the shaping of society."[7]

The culturally significant, socially valued, and long-lasting products of architecture are both the insignia of clients' power and the expression of architects' autonomous artistic aspirations. Historically, the problem of authorship was that the architect had to distinguish his contribution from the power of the patron. In addition to this, modern architects must also fight for place in ever-more-complex rosters of building specialists.

As a form of cultural production, modern architecture must simultaneously convince and deceive the client. For Vittorio Gregotti, this cunning is the architect's critical duty:

Modern culture involves a radical discontinuity: it is a critical culture, it cannot be organic vis-à-vis the society that exists. Because [Albert] Speer and [Marcello] Piacentini wanted to be organic, they interpreted our relation with nazism and with fascism. The typical duplicity of the architect is precisely that of having in mind two different goals simultaneously—architecture as autonomous culture and the client.

Yet, because the autonomous culture of architecture matters only to other architects, they must resolve ideologically the problems of authorship and of "double coding" the object—for the client and for the cognoscenti.

In the public, nonspecialist discourse of architects, the ideological construction of architecture moves on a continuum between two poles: On the one hand, discourse must establish the architect as the creative subject of architecture, proclaiming the superiority of the idea over its realization. On the other hand, it must construct the significance of the created object in a mostly "nonarchitected" environment, emancipating the building from either utilitarian or hedonistic vocations. The rhetorical strategies by which practitioners sustain the collective claims of their profession move imperceptibly from one focus to the other. My argument is that both remain central, even though contemporary professional ideology has abandoned the "strong programs" with which they were once associated.

Let us begin with the architect as subject in Le Corbusier's manifesto of 1923:

The Architect, by his arrangement of forms, realizes an order which is a pure creation of his spirit; by forms and shapes he affects our senses to an acute degree and provokes plastic emotions; by the relationships which he creates . . . he gives us the measure of an order which we feel to be in accordance with that of our world, he determines the various movements of our heart and our understanding; it is then that we experience the sense of beauty.[8]

While few architects would dare to talk in these terms today, the glorified role that architects seek among other design professionals silently evokes them. Architects' willingness to assume practical and legal responsibility for all aspects of good construction (functional and environmental performance, beauty of form and adeptness of space, respect for materials and structural economy) implicitly asserts authorship.[9]

Similarly, the fact that architects' discourse almost inevitably veers toward description or graphic exhibition of their intentions, moves, and

procedures in specific designs indicates another way in which architects claim creative responsibility. Indeed, it is not only the case that architects feel more comfortable with specifics than with generalities but also that the active "I" of their descriptions assigns them a protagonist's role, rivaled only by the buildings they claim as their creations.

The fusion of creation and creator comes through in the prose of Louis Kahn, the great American architect, who reinvigorated the principles of Beaux-Arts planning learned from his teachers in Philadelphia:

Architecture is a thoughtful making of spaces . . . spaces which form themselves into a harmony good for the use to which the building is to be put.

I believe the architect's first act is to take the program that comes to him and change it. Not to satisfy it, but to put it into the realm of architecture, which is to put it into the realm of spaces. An architectural space must reveal the evidence of its making by the space itself.[10]

Architects often say that architecture animates inert matter. This ability of architecture is captured in common language that employs anthropomorphic terms (walls rise and turn corners, roofs drop, windows look down, moldings run, buildings have character) and in more vivid metaphors in architects' discourse (spaces form themselves and slide into one another, fifty-story buildings cannot stop rotating, and an urban square leaks space). Beaux-Arts teaching was centered on the generative properties of the plan—a principle as important for Le Corbusier ("the plan is the generator" that "holds in itself the essence of sensation," he wrote) as it was later for Kahn.[11] The phrase "the powers of the plan" is a specialist's way of metaphorically attributing powers of agency to built space. This metaphor links the architectural principles of modernism to the social-engineering orientation of its professionals.

Incorporating, among other things, the idea of the generative plan, the Modern Movement developed a more absolute principle: The exterior of a building must be an expression of its structure and its interior. But the principle could be knowingly contradicted (as it often was by modernist masters), and the facade could be built up as the boundary between the inside and the outside. Yet the principle that form must follow plan and structure (a more exact phrasing than "form follows function") rephrases the general conception that architecture is the active organizer of space. This is the architectural counterpart of the "strong program" of architectural determinism, which extends (on an ideological level) the agent powers of architecture from space to its occupants.

For an architectural determinist, "architectural design has a direct and determinate effect on the way people behave." Writing in the 1960s, the

sociologist Alan Lipman observed: "In this psychologically and sociologically conscious period, the profession's traditional belief that it satisfies aesthetic 'needs' can be extended to psychic and social 'needs.' It is difficult to imagine a more gratifying belief, one which could better recompense the architect for the vicissitudes of his professional activities."[12] No contemporary architect would credit architecture with reordering social powers; yet traces of the basic metaphor of architectural agency survive. Paradoxically, they inform the formalist emphasis on architecture's aesthetic meaning.

Obviously, architecture must have some purpose and meaning for people who devote their lives to it. The point is that even Richard Meier, an architect known for his uncompromising aestheticism, attributes to architecture the power to create and convey meaning for society in general: "I am not sure [that architecture] shapes or reorders society, but I think it gives some focus, some sense of purpose or meaning that otherwise might not be there in the chaos of our time."[13]

"Meaning" has become an essential ideological justification of postmodern revisionism. Having retreated by will or by force from exalting architecture as an agent of social reform to exalting its single products as works of art, their authors must still insist on making them "speak."[14] Signification, as Meier suggests, extends beyond the signifier.

The idea of communicating through architecture is old. One historian sees in the eighteenth century the emergence of "a tradition in architectural writing . . . of ignoring the origins and importance of 'style' and of explaining architecture away as a consequence or a manifestation of something else."[15] In the nineteenth century, Victor Hugo noted that Notre Dame, "the gospel of stone," had lost its powers of denotation to the printed word; connotation, however, is never lost. It was therefore logical that a profession rendered doubly insecure, by the disintegration of its neoclassicist language and by the revolutionary change in the relations of patronage, would look for justification outside its own canon.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the advance of academicization has changed the substance of architectural criticism and extended its public. Criticism uncovers methods of composition and spatial results that are not only difficult to interpret but even to see by untrained eyes. Yet academicization also promotes the continuing search for external theoretical legitimacy: It goes on, looking to science and technology or, on the aesthetic side, to philosophy and literary theory.[16]

Despite all the talk, architecture cannot be read like a written language: The basic vocabulary of doors, windows, walls, ceilings, floors, and columns

does not compose a text to be read but a building to be lived in. Functional elements and ornamental figures are more readily accessible than "spatial grammars," yet they are inseparable from practical and historical connotations. Therefore, the conventions of building type, the multiple practical functions, and the social origins of buildings always persist as "impure" associations in the viewer's memory.

In sum, theory or, more simply, the esoteric analysis of architectural objects cannot displace whatever it is that the large numbers of viewers or users "read" in them. An obvious contention is that people mainly see size, place, and use in a context that is always already social—a meaning as far from the "purely architectural" as its users' behavior is from being caused by the built environment.

Transcendence and Ideology

In the discourse of contemporary American architects, three ways of seeking transcendence in one's work stand out: First, architects seek to create meaning for their buildings, an effort that can be called signification; second, they emphasize the process, the quality, or the craftsmanship that goes into thinking architecture; and, third, they highlight the enhancement of life that architecture provides as it looks beyond clients and users to a general notion of human fulfillment. These orientations are not incompatible, although they can become contradictory.

In the aesthetic inheritance of modernism, art should not represent something outside itself but should reveal the very process of its making and the conflicts overcome in its creation. For this aesthetics of specialists and cognoscenti, serious architecture is one that shows the tensions the architect has attempted to resolve. As one critic puts it, writing of Le Corbusier's 1930 house in Chile: "[It] displays an intention not only of accommodating the occupants' basic needs but of creating a basic confrontation between architecture as an abstract idea and architecture as craft and tradition."[17] Despite ideal or actual confrontations, meaning, craft, and service all concentrate on the single architectural object. All three orientations to some extent reflect an ideological distance from the obligatory team work of more comprehensive projects; they reflect a turn toward individuality.

Signification

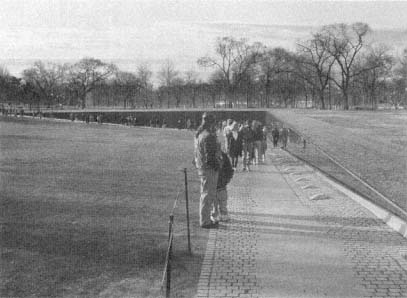

Robert Venturi called on architects to enrich the experience of architecture by making deliberate use of the multiple connotations of the architectural

sign. "A valid architecture," he proclaimed in 1966, "evokes many levels of meaning and combinations of focus: its space and its elements become readable and workable in several ways at once."[18] Contemporary critics tend to see a clear bifurcation in the search for meaning in architecture: on the one hand are the heirs of modernism, who concentrate on signification accessible to still very small circles of specialists and cognoscenti; on the other, traditional postmodernists (who should more properly be called premodernists) deliberately look to the past of architecture for symbolic associations, accepting the "impure" pomp, power, and grace that the past evokes.

I mentioned in chapter 2 Robert Stern's distinction between "traditional" and "schismatic" postmodernism, as well as Charles Jencks's proliferating categories.[19] Whatever the validity of the classifications, all the revisionist tendencies remain within the basic parameters of the architectural ideology. None rejects the identification of architecture as an art, and all equate this art with what architects do. Furthermore, in the revision of the modern, all the tendencies are interested in signification. Even the self-proclaimedly radical "deconstructive" tendency appropriates for architecture the task of communicating the "impossibility of meaning." Here, for instance, is Peter Eisenman's text for a hotel competition in Barcelona:

The resulting form and space no longer can mean in the conventional sense of architectural meaning. . . . In this sense it means nothing. But because of this meaning nothing, another level of potential significance previously repressed by conventional meaning is now liberated. . . . Thus this project not only symbolises the spirit of new Spain in the world of 1992, but also the new world of an architecture possible for the 21st century.[20]

If embodying the Zeitgeist seems a bit much for a hotel, we should remember that formalism elides considerations of program and function and thereby hints at the waning of distinctions between commercial and "high" art.

Signification crosses the boundaries of approach and style, adding its quest for transcendence to the syllogism of architecture. While architects seldom challenge the Western idea of art as personal expression, they professionalize it: Signification (like beauty) becomes a manifestation of their expertise. They and no others will determine what there is to be said and how to say it best. But, of course, to whom they say it (the client, the users, or the ideal audience) determines in large part the formal strategies of architectural signification. Proposing signs that will be legible only to certain publics creates at the same time special market positions for their makers.

For a theoretically sophisticated formalist like Eisenman, being misunderstood and accused of arrogant hermeticism is, on the one hand, the inevitable consequence of being at the avant-garde:

Essentially the profession sees itself as providing comfort. It is a consumer profession, and the elite is not producing comfort. . . . Deconstruction deals with the questions of text and absence and displacement . . . certainly too much for the public to deal with, but it's not too much for a literate public. There is a class of literati, but what is interesting about them is that they have no sensitivity to architecture at all! The intellectual public, which is appealed to by philosophers, scientists, theologians, literary critics, are only interested in comfort when it comes to architecture .

On the other hand, Eisenman is accumulating an impressive international track record from his special market niche: "I get clients, basically, that no one else will get, because there is no one else occupying my territory. I beat Michael Graves in Cincinnati because I took the, quote, 'radical risky position,' the unsettling, unstable position, and I've always done that from the first of my clients. . . . The thing is how do I remain unestablished?"

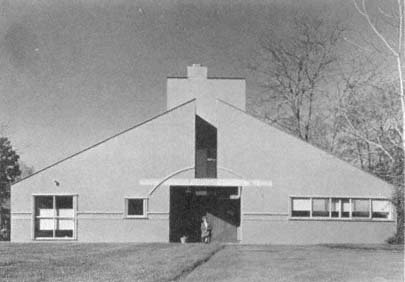

Communicating with the "happy few" and shocking the rest is the classic position of the avant-garde. Traditional postmodernists reject in principle the elitism of this position. With different architectural elements, different measures of eclecticism, and different degrees of reflexive irony or seriousness, architects like Robert Venturi, Charles Moore, Michael Graves, Robert Stern, Stanley Tigerman, Thomas Beeby, Stuart Cohen, William Pedersen, and even Philip Johnson (to mention only some we have encountered) rely on traditional or vernacular forms to make their architecture more accessible. In other words, they aspire to a different and possibly a much broader market than Eisenman.[21]

The different stages of Michael Graves's work illustrate different levels of tension between broadening "meaning" (and thereby reaching a larger public) and veering too far from the narrow professional foundation of fame, toward an architecture that strives to delight on "the other's" terms. Of all the American postmoderns, Graves has probably the most consistently sought to use the simple elements of architectural composition—doors, windows, walls, ceilings, floors, and columns—in a personal language. In the early 1970s, he moved away from an abstract formal repertoire derived mainly from Le Corbusier toward a vocabulary that he thought richer and more intelligible: color and figures and meanings taken from the "high" traditions of the Renaissance and mannerism. He explained his gradual shift from schismatic to traditional postmodernism this way:

We can't have any purposeful ambiguity in our language unless there are abstractions. But at the same time we run the risk, if we are not figurative enough, of losing our audience. There has to be some balance between what is figurative, what is associational, what is understood as symbolic in terms of its figural association, and what is multifaceted in the sense that the abstraction allows the several readers . . . to read what they want into the composition.[22]

For the historian Alan Colquhoun, Graves's formal choices reflected a "nostalgia for 'culture' which is characteristically American, and . . . depends on the existence of a type of client who has similar—though less well defined—aspirations." Graves's work of the late 1970s was becoming "a meditation on architecture," in which "the substance of the building does not form part of the ideal world imagined by the architect. . . . The objective conditions of building and its subjective effect are now finally separated." Graves's architecture was becoming image.[23]

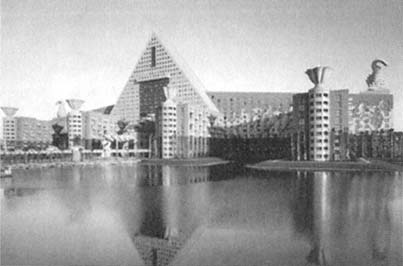

In the 1980s, Graves's work for an emblematic client, the Disney Corporation, completed the passage toward an architecture that is pure sign. Disney epitomizes the culture industry's tremendous capacity to create mythical figures and the most effective simulacra of real "places." The audiences for these images never share in direct social relationships—the lifeblood of traditional communities and autochthonous myths.[24]

Doing architecture for Disney sends multiple messages beyond the buildings themselves. In the new world of indirect and mediated social relationships, Graves's implicit message to architects is that architecture as it used to be can no longer compete with the connotative powers of the culture industry. In the Swan and the Dolphin hotels at Disney World, Graves designs "cosmic cartoons in toto, their shapes abnormally few, obvious and vast."[25] Yet "entertainment architecture," as the company defines it, and expensive hotels designed for "vast conventions of sober-suited executives" are not cartoons. In a tightly controlled private town with not a shadow of democratic government, the architecture points beyond itself and beyond Mickey Mouse: The Magic Kingdom represents a phantom public life—one, however, that must be paid for . The architecture, like all the other forms of delightful simulation, is a piece in the vast marketing strategies of the archetypal postindustrial corporation.[26]

Precisely because they represent extreme cases of image-making, Michael Graves's brilliant designs for Disney illustrate inescapable problems of architectural signification. Walter Benjamin, the Frankfurt school critic, saw architecture as "the prototype of a work of art the reception of which is consummated by a collectivity in a state of distraction." He saw that architecture, like the cinema to which he compared it, pointed a way

out of the "rapt attention" and the reactionary aestheticism that surround art in Western culture. Architecture, embedded in social relationships, was appropriated habitually "by use and by perception or, rather, by touch and by sight."[27]

Benjamin was wrong about the culture industry. Disney's world of paid entertainment proves that most people pay attention not to architecture but yes to the fantastic images and associations it connotes. The viewers do not relate either to each other or to the architecture by habit or use but rather by the imaginary bonds of spectacle.

For the critic Mark Girouard, modern architecture had failed "to produce images of enjoyment or entertainment or images of domesticity with which any large number of people could identify."[28] The case of Disney architecture, like the architecture of films to which it is so close, reiterates the dilemma of contemporary art: caught between the esoteric advancement of a specific art and signifying something for a broader public—essentially by giving it what (artists think) people want. Only world-famous architects, whose names have market value, actually ever face a choice that stark. Even so, the client always has the last word.

With clients less experienced than Disney in the creation of images, the choice is already made: Architects who aspire to make a mark on architecture—the subject of professional discourse—seek the client's license, in order to communicate with those who pay attention. Thus, despite Venturi's original pleas for a nonelitist "pop" architecture, the traditional revision of modernism has been identified chiefly with the revival of the neoclassical language and with the search for a vernacular style.

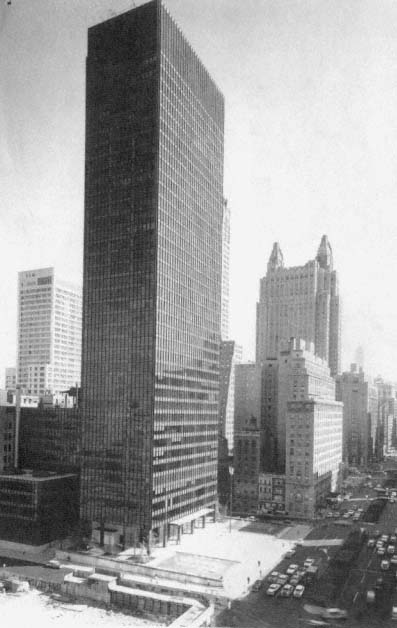

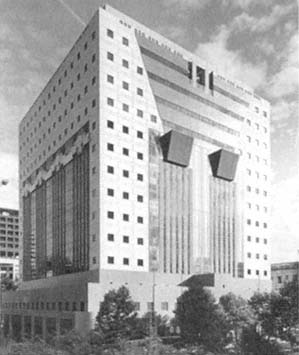

Contextualism, the hallmark of postmodernism, inflects the architecture of single buildings toward the discovery or invention of vernacular forms. For the public, contextualism tends to mean only conformity with what is already there. For the designer, it means that signification emerges from the insertion of one object within a preexisting system of built objects and from their spatial and temporal relations. The predominance of neoclassicism (among other high styles of architectural history) has a reason: it has a long history in the urban environment. In the visual and vital chaos of many modern cities, there is no vernacular and no discernible "context" capable of ordering the design of single buildings. In this account by William Pedersen, we detect an almost inevitable return to the tried language of the "high" architectural tradition:

Since most of the contexts we were building in gave off confusing and contradictory signals, wasn't it possible for the building itself to be composed of different pieces, each drawn in reference to different conditions within the context?

. . . Certainly, a large building could be more sensitively scaled to the city if it was made up of distinct pieces. . . . [But] the individual building could only go so far in representing the complexity of the city. Consequently, our buildings became less complex. . . . The issue of the tall building, addressing the public realm, presenting a facade to the street which would join other buildings to make a continuous and cohesive unity out of the street, became a dominant preoccupation in our work. We started to introduce classical compositional techniques, primarily those that were aimed at encouraging the textural environment and unification of surface.[29]

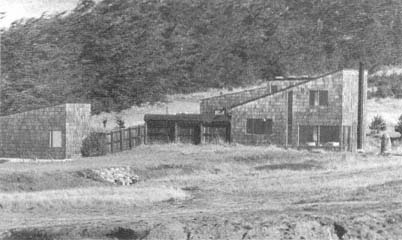

In suggesting the difficulty of contextual design, Pedersen shows that accommodating the single building to its environment can be a supreme expression of architectural craft. A new object can be fitted into its surroundings if the architect pays enough attention to detail and creatively interprets the past and present context. But it can also be made to fit in mass and facade if the architect uses rapid gestures and a silhouette, vocabulary, and ornament that satisfy zoning boards and commercial clients. The emphasis on craftsmanship does not reject signification but the quick creation of illusion.

Craftsmanship

Architectural craftsmanship requires care, technical competence, proverbial attention to details, subtle handling of spaces, efficient and elegant interpretation of the program, and ingenious and sensuous use of materials; above all, perhaps, it requires considering the consequences that each move implies. Craftsmanship takes time —and time in architecture is, of course, money. An inventive designer can achieve scenographic solutions and brilliant effects in less time than it takes the craftsman architect to design a small building. This is one reason developers are not the latter's typical or choice clients.

Craftsmanship entails a reverence for embodied perfection. The perfect objects produced deserve permanence and respect. Indeed, craft-oriented architects emphasize that their designs will last—or would last, if construction was as good as the care that went into the designs. Well-crafted architecture seems "naturally" contextual, like the architecture the great Bay Area architect and educator William Wurster called anonymous—so married to the site, so simple and so lasting, that it looks like a Tuscan farmhouse or a wood barn in California, something that has always been there. For Joseph Esherick, an architect in Wurster's tradition, "the ideal piece of architecture is one that you don't see." The disappearance of the architect as creative subject is, of course, a rhetorical strategy, for viewers and

users know that these perfect syntheses cannot just happen, that an invisible human subject was responsible for devising what was made to be forgotten.

Although independent of size, well-crafted architecture connotes both an emphasis on control and a close relationship with the client, both of which seem easier to obtain in the design of smaller projects—notably private houses, unique commissions in which the client-user has a personal stake.

Houses occupy a large place in Stanley Tigerman's practice. Predictably, he sees small projects as a much more fertile ground than large-scale buildings for the development of new architectural ideas. This is, in part, because small buildings admit his playful vision of architecture "as commentary," even as joke (as in Bruno Taut's motto of 1920, "Down with seriousism!"), while all the enormously expensive "humorless buildings . . . are the joke." The owner of several south Florida burlesque houses, dying of intestinal cancer, came to Tigerman to ask him to design a beach house. Tigerman decided he could only try to make him laugh. Accordingly, he developed (and explained to everybody) the plan of the very successful "Daisy House" as a phallic emblem. Ten years later, its main occupant was still alive!

Tigerman's account of his practice typifies the emphasis on craftsmanship, including the ideological notion that the match with the client is "made in heaven":

It's like when I was a teenager, you would see an attractive girl . . . you'd never let her know that you wanted to go out with her! You wanted her, somehow , mysteriously, to find you. So I have been waiting for them mysteriously to find me. I don't want to find anybody. . . . I just want to sit and do work. Of course, I don't want too much. . . . If you have too much work, you can't do it well. You can't. You start doling it out to the people in your office to do. I only want the work that I can do well . . . . Whatever it is. If it's a back porch, a little store, a house, a skyscraper, a business, it's a building! I want to do what somebody comes to me and wants me to do. . . . I don't do marketing. I resent architects who do it. What I think an architect should do is sit in his or her office and work .

Tigerman is such a public figure in Chicago, so active talking, writing, teaching, drawing, exhibiting his work, and organizing events, that it might indeed be true he does not need to do more than that to find clients. As we know, discursive activity is a necessary amplifier for the craftsman-architect's work. Yet discursive activity is not quite enough for Tigerman; he may prefer his small practice, but he has been actively involved with

Stern at Euro-Disney and with Bruce Graham of SOM in the now defunct possibility of a Chicago Fair.

In theory, craftsmanship should not be a primary orientation toward architectural work but an ancillary one, an orientation to supplement others. It can be pressed, of course, into the making of architecture as art with meaning of its own. Yet, as Holmes Perkins perceptively notes, originality and craftsmanship are two different dimensions, and architectural judges perceive them as distinct and reward them differently. When Perkins was at Harvard in the 1930s, "the people who were real leaders in our eyes were breaking new ground. . . . One of the dilemmas in breaking new ground is that the new is almost always crude, and it takes maybe another generation or so to polish it up. I think the difference between the polished up version and the original is very very visible!" Because craftsmanship ultimately chooses integrity of process over other aspects of architectural work, it may orient itself toward "perfection," away from the possibility of failure (which lurks in expressing "meaning" or, simply, original ideas). Yet because craft work recognizes the primacy of the client's needs, it has affinities with the form of transcendence that I have called the enhancement of life.

Enhancing Life

The close relationships that architects like Tigerman establish with their clients show their concern for their clients' purposes. In addition, architects show a concern for clients' lives that is typical of the architectural craft.

Architectural craftsmanship tends to see architecture as providing a setting for social life. Speaking for many architects, Joan Goody declares, "It's a bad setting if it obstructs that life and makes itself the star." She describes her idea of a good setting a little less modestly:

Architecture . . . can be intellectual in the way it is conceived, but it's got to appeal to the senses once it is built. . . . It feels good when light enters in such a way that it opens up a space rather than making it oppressive or cramped; when the proportions of a facade feel comfortable, in harmony; when the materials, colors, textures are appealing to the eye. This is a sensuous reaction, as opposed to an intellectual one, where you need a scorecard to understand that one piece of a structure alludes to something that's three blocks away and another is an ironic comment on something else three centuries away. I think one should be able to respond to a building with one's eyes and one's body.[30]

"Feels good . . . comfortable, in harmony"—these are dimensions of architecture that a theoretician like Peter Eisenman despises. While all

professional architects (and all professionals!) try in different ways to ennoble the service they render for money, this form of transcending mere service tends to steer architects toward certain types of clients and especially users. The aspiration to enhance life by means of architecture rises above the commonplace by exalting the concrete needs that are served. Therefore, its choice settings are those that represent the needs of everyday life: houses, workplaces, roads, airports, schools, community centers.

Insofar as the first motive is not profit but augmenting the quality of life, the creation of new needs (or rather, the direction of unrecognized needs toward new forms of fulfillment) is the contribution of all professions to the civilizing process.[31] Architects who spend unpaid labor time on projects they hold important seem close to that in intention.

Joan Goody, once again, illustrates how to serve unrecognized needs. In my interview with her she discussed the renovation of worse than half-abandoned public housing at Boston's Harbor Point. Cross-ventilation had been the overriding concern of all public housing from 1945 to 1960, resulting in the cross-shaped concrete towers "tossed around" in such a way that they "line up next to one another and become a single wall." Her "selective demolition" has re-created the traditional grid system of streets and opened each one to a vista of the harbor. Besides making it safe for people to get home, "the point was to get people to walk on the street."

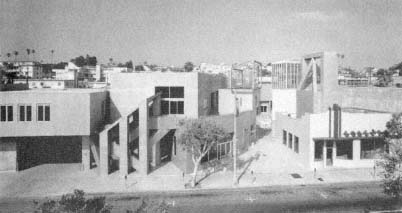

Rob Quigley explained that the single-room project for the homeless "was neither an apartment building nor a hotel, and the building codes penalized the design of such an animal," and then described almost apologetically how he worked on the developer's idea: "A working wall that incorporates the toilet in the room, a sink with garbage disposal, a spot for a microwave oven for rooms that are 10 by 10 feet. These are simple little trivial things, but it is a precedent setting idea, that you can have a bathroom not legally called a bathroom. . . . What it means in comfort, dignity, sense of privacy to not have to walk to a common toilet at night is unmeasurable." Not surprisingly, Quigley echoes the vision of the Frankfurt architects in the 1920s, the vision that Paul Tillich called "a religion of everyday life."[32] The issue here is not transcending service but, much more ambitiously, transcending life itself by enhancing its "everyday-ness": making efficiency gracious and grace efficient.

The aims of architecture, as Sir Henry Wotton defined them in 1624, were tripartite:

. . . the end must direct the Operation.

The end is to build well.

Well building hath three conditions:

Commodite, Firmenes and Delight .[33]

Few elite architects are inclined to care about comfort only, and few define signification independently of delight, except, at their most theoretical, the "deconstructive" architects with their philosophy of "violating" and rupturing form. Most architects seem to believe that "delight" is still possible and acceptable in a world like ours. Too often, they slide into believing that beautiful architecture is good in itself.

The central objective of ambitious design is to achieve this good and the "firmness" that will make it last. To their peers and to interested circles, architects of recognized talent seem able to achieve it more often than others. In the following chapter, I examine, first, how they explain the process, basic to their work, which they call design. Second, I consider the revision of modernism through the eyes of its protagonists, exploring how it has affected their way of conceiving their work.

Chapter Six—

Design and Discourse in a Period of Change:

The Protagonist's View

To Reyner Banham, the persistence and centrality of drawing, the Renaissance disegno, make for the distinctiveness of our building art. It follows in his logic that computer-aided design may well have destroyed the mystique of drawing, and hence of architecture, "not by mechanising the act of drawing itself, but by rendering it unnecessary."[1] Obviously, the process of design includes an ability to draw, as well as the much more basic competence to read two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional space. But my analysis will show that Banham greatly underestimates the complexity of what architects call design.

I begin with two eloquent accounts by Adrian Smith and Diane Legge, both of them partners at SOM-Chicago. Their firm makes available to them the most sophisticated computer technologies that exist and the technical support required to use them efficiently. It is therefore instructive to consider how they describe the formal origins of a design. In studios, architects draw as they speak about what they draw. But the accounts presented here do not rely on the combination of "drawing and speaking," which Donald Schön identified with "the language of designing" in direct observations of teaching studios. Yet, Smith and Legge think in terms of the "normative design domains" that Schön recognized.[2]

Both Smith and Legge are explaining to a lay interviewer (with faint echoes, perhaps, of how they talk to clients) the emergence of a composition. In Smith's account, siting and form predominate; precedent and the "felt path," the user's experience of moving through the created spaces,

are most salient in Legge's. Both make brief technical references, either directly to structure and technology in the case of Smith, or indirectly, by representing problems in the language of measurement or by common technical notations such as "scale" and "section." Both give much importance to the constraints of program; Legge alludes vaguely to those of cost.

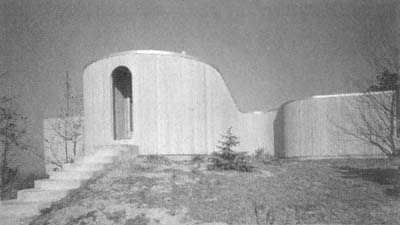

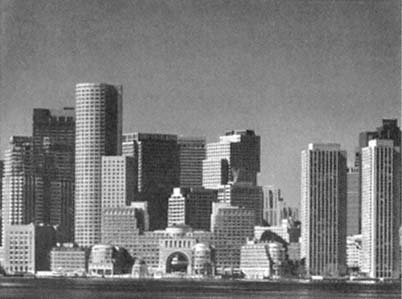

In the language of the French Beaux-Arts, architects often call their first approach to a specific design problem the parti: in Stanley Tigerman's words, "the plan-wise organization of something, typologically, categorically, so that you can understand it formally, not by function, but by formal type ." Adrian Smith explained the genesis of a parti for the Rowes Wharf complex on Boston Harbor, an invited developer-architect competition that SOM won out of a field of eight. The Redevelopment Authority's guidelines required that the Broad Street axis remain open down to the water, and Smith's solution ultimately included a spectacular arch spanning the space between two corps of building:

As you look at the city from the air . . . as it hits the water's edge, it fans out: You see all these finger piers sticking out into the water. It was just very apparent that this building had to have a continuation of those fingers sticking out of the water and that there should be an urban edge which relates to the strong street that rims it. In between the finger piers and the city is this highway that makes a very strong kind of figural piece through the city. . . . The client and his people and we, we all felt that we wanted to have some strong kind of figural piece that could be identified and identifiable as the project's memory of things.

Smith is not talking about composition but relating the genesis of a governing conception. The idea, at this level, is still vague; if it involved drawing, it would be one of the rapid sketches (sometimes clay massings) with which lay people identify, so wrongly, the architect of genius. The configuration of the site plays a determining role, which is immediately modulated by the guideline's constraints and the client's wishes; as Smith continued, he moved quickly in technical and political directions: "The arch came about from the fact that we had to span about 80 feet. If we built over it at all, we had to span it. . . . The arch became an important kind of entry way into the city. Our initial designs did not have it, because I did not think we would win the competition if we spanned over [laughs], but after we won, we were allowed to change it!"

Diane Legge reiterated the primacy of a governing idea:

All of the work I had done in architectural school, plus the work I had done for firms, was very small-scale. It seemed to me that a large project probably was, in a sense, a collection of smaller projects put together. In the end that's how

you tackle it. . . . [Yet] in order to work at a large scale you have to think of it as a single problem. . . . We try to reduce it basically to one overriding idea that directs this very large project. Once that idea is established, and you have tested it and made sure that it will work, then that idea translates itself into different subsets that influence the components of the project.

Her commentary summons up the idea of the architect's governing role in a complex design process. This role is in almost perfect correspondence with the role that primary producers assume in the flexible, "postindustrial" organization of production.[3] Her concrete example is a vivid illustration of the architect's imagination at work:

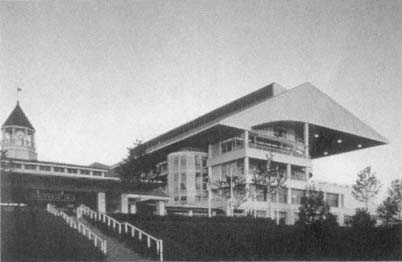

So, for example, I am working on a race track for Arlington park. . . . We believed that the overriding idea of the grandstand in the new complex should be a long, low building in the tradition of the older great race tracks. . . . (But we have a much more energetic and large program than you normally see in European race tracks; you can see in section it is a tallish building, because you have to get up to 30,000 people in it.) . . . The magic of racing is being outside and seeing the horses. So that was the basic idea. Now, how do you carry that out? You've got to keep the grandstand open; it has to have a roof, but it is not enclosed. The building is as long as we could make it: 800 feet long. (We really can't make it longer than that because of price constraints.) The paddock . . . needs to be a place where the pageantry of horse racing in the greatest tradition of the sport is played out, and so we've brought in earth: It's an amphitheater with a great walking ring at the center, and people move from the building out to the track and back into the garden space. So the long, low relationship . . . to the ground, to the scale of the horse, of a person, is played out through the whole building. . . . And yet, 30,000 people can be there at the same time, all experiencing this flow of "look at the horses, go out and watch the race, come back and look at the horses," so there is a flow back and forth. . . . You think of the massing of the building being long and low in the traditional sense.

In Legge's account, the building's particular looks come well after the directive form and the program:

Then, as you begin to think of the exterior, you still keep that in mind. . . . So we looked for the larger buildings that you see in the Midwest, and actually barns and stables were very close. . . . The building is all in white, it has clapboard siding on it and long verandas and porches on the back, so it always has a sense of the barnlike roofs that you see in the Midwest. It's all white, like all our barns here, and stables. And you just keep layering and layering the architectural ideas and solutions onto the original concept.

Smith and Legge can use computers both to generate drawings or materials specifications and to simulate how a building would look in its urban context (SOM's software can take a specific site in a specific city and peel it away, like an onion, from different viewing points). Yet there is no way

that a computer could have provided the creative effort that seems guided by experience, by the intuition of directive form, and by constraints. In these accounts, the process of design apparently begins, in Diane legge's words, by synthesizing "literally thousands of ideas and bits of information in our heads."

Both accounts are highly contextual. In Smith's, the urban context seems to immediately suggest the form; the arch is identified later as a physical and symbolic organizer of space—a gateway to the city. In Legge's explanation, the context consists of precedents, which she first takes from traditional interpretations of the building type (she accepts both the character and formal conventions of the race track grandstand) and, second, creates from a Midwestern vernacular, regionalizing a design characterized by its type. Her eloquent references to the imagined movements and evolving feelings of clients inside the building suggest how good she must be at talking to clients.

Neither Smith nor Legge refer to "high" architectural precedents. They are both talking to a lay interviewer, and it may be that only architects with an academic bent commonly use historical antecedents as a sort of shorthand in conversations among themselves. Contrast their accounts with this excerpt from an interview that a Chicago architect conducted with Thomas Beeby (just appointed dean at Yale) about the firm's work:

Right, there is a progression. First, National Bank of Ripon and the Fultz House were both sort of Miesian/Palladian schemes, with nine-square-bay partis . Then, with the Champaign Library and Hewitt Associates, . . . there are free-form figural elements, vaguely Corbusian, as filtered through John Hejduk, juxtaposed with the more Miesian, orthogonal pieces. . . . The bank in Northbrook . . . comes from Kahn, but is also based on a little tomb by [Friedrich] Gilly. It's German, super austere classicism. . . . There used to be this magic little book floating around here, the German neo-Classicists. . . . It had Gilly, von Klenze, Laves, as well as Schinkel.[4]

To the layperson, the account seems unbearably pedantic. It suggests, however, that elite designers may well take their formal cues directly from the evolution of types or from architectural history, while nonelite followers take it from what is current. If this hypothesis were true, then while Beeby looked at Schinkel, the ordinary architect would look at what Beeby published or at SOM. In any case, the architect's creativity does not consist of inventing original forms but in discovering how to use form as a directive concept.

For Donald Schön, designing is a reflexive "conversation with the materials of a situation."[5] The designer evaluates the implicit potentials of some

initial decisions and considers them in the light of criteria drawn from the normative design domains (see note 2). But constraints were weak and cost did not play any part in the teaching situation Schön studied. Contrast how Charles Gwathmey describes a work process in which thinking-as-drawing plays a large part:

Bob [his partner, Robert Siegel] and I talk the problem through at length, all the aspects of it. We evaluate all the information and all the constraints and prioritize the components of all the parts of the problem: site, overlaid with program, overlaid with budget . . . . We get a deep picture of what the problem is. Then we respond as architects, not as philosophers or theoreticians. We take notes that are drawing notes about form and plan and section simultaneously. Quickly, right after that, there is a notion of image, but it is not preconceived. And we try to make a building . . . whose idea has longevity . . . strong enough in its own right and tolerant enough to adapt, to readapt, to be renovated, and still to withstand as a recognizable valid idea. (emphasis added)

All architects repeat that there is no good architecture without a program, which means that there can be no real design work without constraints. Constraints also mean that the emphasis on one directive concept in Smith's, Legge's, and even Gwathmey's account is either provisional or a rhetorical strategy. Once the real process of design gets going, devising alternatives becomes an integral part of it. William Pedersen gives another reason that alternatives are fundamental to designing:

It is one thing to design a building, and another to convince a client of that design . . . . I presented [to the City University of New York] what I thought was an excellent solution, but because it was the only solution I presented, I gave them no means of comparison. . . . An architect has the obligation, I learned, to present many possibilities. Then the logic of the right choice will be more evident. I went back and worked out six or seven alternate schemes and presented them in clay massing models. The next presentation went much better. I had given them the tools by which they could get involved in the problem.[6]

The overriding importance of program and constraints in real design situations suggests, in fact, that the active part of designing involves politics more than drawing or even imagining. Politics means, among other things, trying to commit the client to an idea and deciding what and when to compromise. Joseph Esherick speaks for many architects in affirming: "When I spend time talking to clients, I call that design . Same if I am arguing with our central engineer."

For elite architects, design is emphatically not only drawing, nor even essentially drawing. It is both creative synthesis and an eminently political activity: the negotiated assumption of full responsibility for construction.

The directive ideas of form (and, just as important, the details of the plan and the construction) must be expressed in the technical language of architectural thinking-drawing. Yet two collaborative and potentially conflicting processes are essential in the formation of ideas and details: What Steven Izenour of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates calls "the tussle" with the client and, just as important, the ongoing critique of a collaborative team. When architects emphasize program, they evoke the client's active or silent presence. But the profession's traditional ideology of charismatic authorship and the related emphasis on directive, and therefore singular, form tend to ignore the vital collaboration of the team. In the offices of great designers, ideology insures (at least for a while) the professional staff's complicity with this neglect.

Returning to the acknowledged "tussle" with the client, Denise Scott Brown's story about the firm's and Venturi's approach to design suggests that excellent designers listen perhaps better than others; however, they also know how to stand firm for their directive ideas, once they are formed.

A lot of times people say things like "You sound as if you really listened to us. You didn't look as if you were going to ram something down our throats." That's very important. Bob listens. But there comes a time, and it may be a year into the process, when he says "Look, it's been decided now. Don't try to change pieces because it won't work that way." . . . The president of Princeton [University] tells a beautiful story about it. One of the trustees had questions whether that flattened column with the tiger on top in front of Wu Hall should be there at all, and whether it should have a tiger on top. Bill Bowen pushed Bob. He imitates Bob crossing his arms and saying: "I am perfectly happy with my tiger." And Bill Bowen said "OK." . . . You try to be as negotiable as you possibly can, but there comes a time when you can say, even in the tussle , "Look, for the way this building is happening, you really do need the stairs going in this direction. If you go in the other, then we will need a whole new point of departure, a whole new philosophy." Saying "take that element off the building because I don't like it" will lose you your architects. The architects will feel their baby has broken a leg.

So, good design is clearly more than satisfying the client. It is, in Cesar Pelli's words, "choosing what you can control, because you cannot do everything." It is quitting a client who wants to mix and match parts of different alternatives, as Joan Goody did, because architecture is not "a Chinese restaurant, where you order one from column A, one from column B." It is Frank Gehry talking about the program for the Los Angeles Disney Concert Hall to the members of the orchestra, one by one, to help them find the "Ten Commandments" essential to the project: "One is the fidelity of the musical delivery, and with that the experience of listening to the

music which connects with the way the lighting works and the room is designed. That means you cannot select an acoustician who comes in and says 'Either you do it this way or like that' because then . . . you are saying that the acoustics is more important than the experience of listening to the music."

In sum, not all design is a political activity: Good design becomes political because its authors have a competence, and often a reputation, on which to stand, and that gives them authority and something to defend. This competence is complex. It consists not only of aesthetic talent, which must bow to the belief that "everyone has his own taste." It does not consist only of thinking-drawing formal ideas that organize space. Good design is imagining building. Among other things that mere building technicians do not normally pursue, this implies the sensitivity to materials for which Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn are rightly famous.

The architects I interviewed still speak eloquently about materials. Materials do not matter to the architectural imagination because they are precious. Although elite architects like the luxury of expensive materials, they insist that architecture does not depend on it; somehow, they are more articulate when they talk about cheap materials, perhaps because there is not much that needs to be said about travertine, except that it does not age well in certain climates.

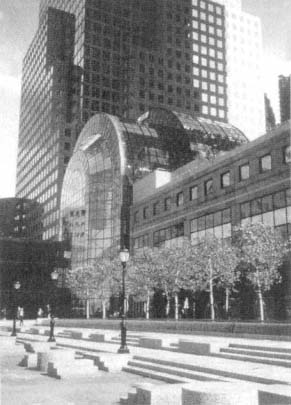

For instance, Cesar Pelli's long-standing interest in the architectural possibilities of glass dates from his work in the commercial practices of DMJM and Gruen, to which clients came "looking for building, not for architecture." As a designer, he was free to concentrate mainly on the building's enclosure or "skin," for the designs were for the most part standard spaces. Pelli explains that his commitment to glass as a material that is both cheap and architecturally "active" dates from that period:

Several architectural decisions were necessary to create the appropriate conditions for the delightful surprises of interpenetration and overlap. First is the dominance of the glass wall; the glass is not contained in a frame or hanging from a fascia. Second is the presence of a thin grid of mullions that define the surface of the glass and the form of the building. Third, the thinness of the mullions and their minimum projection . . . do not obscure the reflections; they help maintain the plane of the glass and the tightness of the surface. Fourth, the choice of tinted glass. . . . Fifth, the balance of outdoor and indoor light, which allows both reflections and transparent perception to take place at the same time. Sixth (although minor), the glass wall brought to eye level, where most of the points of reference, inside and out, occur. Seventh, the position of the building in relation to its immediate environment; the environment becomes absorbed in the architecture; through transparency the figure becomes ground and in the reflections the ground becomes figure.[7]

A cheap material like glass became a worthy substitute for stone and a hallmark of classic modernism; Pelli suggests that the fragility and transparency of glass make it now a symbolic medium for a new phase of our modernity.

Frank Gehry also became famous while using the humble, mass-produced materials of the industrial age. The choice was initially dictated by economics: Gehry worked for a long time with tight budgets, very unlike today's $100 million budget for the Disney Concert Hall. His imagination, primarily similar to that of a plastic artist, found enormous possibilities in omnipresent materials like corrugated metal and chain-link fencing.

What fascinated me about the chain-link from the beginning (I never liked it either!) was that the amount of it that's been installed into the world culture is staggering! And there was so much denial about it! And when you used it intentionally, everybody hated you for it, and that really excited me! . . . I said in one lecture "I do not know what's ugly and what's beautiful," and it got quoted. I said it in the spirit of a lawyer who asks "What is the law?" It's a good question to ask. . . . "How do you put a box around this thing they call Law?" How do you put a box around beautiful and ugly? I've been confused about it because things I find beautiful sometimes are the things people find ugly, and vice versa. And they have immediately tagged ugly something that's made with cheap materials.

His friend, the painter Michael Heizer, thought that with expensive, lasting materials there could be a chance that someone, some day, would eventually like Gehry's work. But Frank was more interested "in the momentary and what was going on and how I saw it" than in architectural permanence. The irony is that his stucco and chain-link are holding up better than the precious, fancy buildings: "No, it won't last the two thousand years! but I did a little house in stucco that looks as good as anything, and that was 1964. . . . There is a little travertine building down the street that Dan Dworsky did. The travertine is not as nice as it was; it has lost its feeling, it has lost its spark, where my funny little stucco building has retained the energy I put in it. . . . It's the idea that counts more than the object. " Whatever the size, the scale, the function, the environment, and the cost of a project, architecture for these architects should be about ideas that transcend mere service to a program. While drawing is only a specialist's "language," design is the creative process (technical and political, hence collaborative) that gives content and substance to the ideas. The process is so complex and so difficult that ideas have to be controlled: Ethically, they should not interfere with the client's needs (in practice the client often has the power to forbid this interference). Joseph Esherick says about Frank

Gehry and powerful architectural ideas: They "can actually help solve the very particular problem that he has in front of him. But not if he lets his search for a particular Weltanschauung get in the way. . . . I think he will always remain responsible to the task at hand. Nobody ever said that you cannot give to a project more than what's in your contract." Ultimately, Esherick believes there is so much to think about in designing architecture that it is pure romanticism to think one can even remember the Zeitgeist:

That's the problem with historicism: You've got so much to do that you cannot assume a historicist position without excluding the whole process of design. Nobody I know can integrate it into the complexity of the issues—the methods are sloppy, vague, heuristic. . . . What really happens is that they solve the problem by very ordinary methods and then they lay all this historicist junk on it. It is a sort of add-on thing. The same if you have some particular world view: You have one, and it exists, but I wouldn't be able to consciously go through designing with the idea that somehow I am going to express my world view or that of my social group! It is conceivable that I may have two different ideas (and I consider it a failure if I only have two!), and then I might say which one is the more likely expression of my particular world view. . . . You can never tell, I might take the least likely! The process is very messy and, you know, you just do it!

Good designers trust their own competence. Professional and artistic self-confidence are necessary for the apparently arrogant task that involves imposing a form upon a site and taming a program, if necessary by means of an arbitrary discipline. In the legend of the genius architect with a manic ego, the formal discipline is an act of the creative will, but, as the designers tell us, architectural form is never invented. It is taken from a historical and typological repertoire and from a canon that, it is true, has been broken open by architecture's most recent evolution. It is to the architects' personal visions of this process of change that I now turn.

Modernism, Postmodernism, and Beyond

This is not the place to review the flood of literature on modernism and postmodernism; while architectural discourse may have started the flood, it is now a small stream compared to the rivers of literary criticism and philosophical debate. The American architects on whose views I draw belong to different generations, represent different types of practice, and are at different stages of their careers; nonetheless, a majority of them have played an important role in the revision of the modern. Postmodern revisionism is in part a generational challenge. It is intertwined with the intellectual construction of "modernism" as its target. How architects view

modernism and its revision obviously depends on their age and professional status; less obviously, the kind of professional transcendence to which they aspire influences their construction of the postmodern passage. They are able to say more about the passage itself than to draw a conclusion from an evolution still in the making. Tolerance of eclecticism, which has replaced the International Style, appears to have left them with a sense of malaise, as if something very important had been lost and could only be recaptured now as a historical memory.

The Defense of Corporate Modernism

Since challengers and defenders need to construct their enemy, it is helpful to start with an interpretation of modernism that brooks no doubts about how it was practiced in the United States. For the late Gordon Bunshaft, "the period after the war, until about 1970, is probably the greatest and most unique building period in the history of architecture. . . . We were building a kind of architecture that was not derivative from anything—maybe that will be bad or good, I don't think anybody can judge now, but it was unbelievable and it became worldwide and there was a tremendous amount." Bunshaft does not distinguish the derivative modernism appropriated by American business from the modernism of Le Corbusier (as much his idol as most revisionists') and Mies van der Rohe. Formally, it is the same architecture, and his generation "owned" it. He does not see any difference either between his kind of modernism and the schismatic revisions of architects who try to redefine modernist aesthetics at the source: "The best work that is done today is all modern." There has been no revision. Bunshaft limits the postmodern challenge to the eclectic historicism of the "gray" variety ("ugly on purpose," like Venturi's buildings, or "freaks," like Graves's, or "copies," like Stern's), and it has failed. He complains about the proliferation of Venturi's lunette windows all over Long Island houses (yet he does not consider houses "important architecture") but never mentions the modernist glass boxes that spread all over the world mainly because they were relatively cheap to imitate. He caps his defense by resurrecting the aesthetic enemy of the 1920s and 1930s modernists: "Victorian is now back. If somebody can tell me there is any aesthetic quality in Victorian, I'll eat my shirt. It's all heavy, clumsy, and overstuffed."

Bunshaft's polemic traces an unbroken formal line from the beginning of our century to the 1970s. Other defenses of modernism admit its formal complexity, as does Bruce Graham, who belongs to the cohort of SOM-Chicago partners following Bunshaft.

Graham takes care to distinguish the American modernism of the 1890s from that of Europe in the 1920s, which was "a highly revolutionary movement, inspired by painting and poetry, against the history of Europe, against imperialism, and mainly against the First World War." The first American modern architecture, as Sullivan and Wright have themselves claimed, "was actually a result of building cities in a hurry . . . rather than a negative idea. And it was a search for a democratic expression in architecture, one that expressed the people. . . . The European movements were completely devoid of decoration, while Sullivan and Wright were decorative, and [their] symbols, like the onion, were symbols of Chicago and the Midwest." But when Graham drafts a sanitized version of post-World War II modernism, he does not maintain his previous distinction between ideological and commercial orientations. Graham's Hancock and Sears towers were going up in Chicago when architecture, like other professions in the late 1960s, began to stir. In the late 1980s, Graham was about to retire but was still at the apex of professional power. In my interview with him he took the 1988 special issue of Progressive Architecture on private houses and dismissed all but one from the field of architecture with a common theme: "What does this mean to building cities? It's fashion, it's nice, but so what?" This rhetorical move is an integral part of a defensive reaction to the attack on the modernist aesthetic.

Graham (like Bunshaft) appropriates postmodern contextualism for his side, citing the convincing example of his Banco de Occidente in Guatemala City ("The building is not air-conditioned, it is all naturally ventilated, naturally lit, with colors that deal with Guatemala, which is not the same as Mexico, quite different"). By avoiding the accusation of ignoring (or destroying) the context, an accusation frequently waged against the International Style, he thus opens the way to a protective account of the architecture of the 1950s and 1960s: It was only the result of what clients wanted and of what a public insensitive to cities allowed. On the one hand, government ("with a lot of influence from Europe and a lot of Easterners who looked at it as social scientists") dumped people into buildings that were "abstractions."[8] On the other hand, clients prevented architects from putting shops on the ground floor "to bring people in and make the building part of the street."

The 1960s changed the public's perception of buildings and their role: "At first, it was probably in universities, not so much Vietnam, as simply a consciousness of looking around and seeing how ugly things were. And that because a power for architects to use, so we used it " (emphasis added).

Graham credits Jane Jacobs for much of this change. But for younger architects, it was Vietnam.

The Populist Challenge

Stanley Tigerman makes a forceful connection between events of the 1960s and the discourse of his profession: "Bob Venturi was to architecture what Vietnam was to America: . . . They both made the subject fall from grace. . . . The Vietnam War was one of the most stunning examples of a country coming to grips with its own imperfection. Similarly, architecture was thought to be high art . . . until Venturi came along and pointed out that Las Vegas was part of our heritage and that this was OK."[9] Instead of focusing on the confusion of the 1960s and the complexities of architectural discourse, I will take the postmodern challenge strand by strand.

In the excerpt above, Tigerman, like many of his contemporaries, combines two distinct processes that converged for a time in the delimited field of American architecture: One was the broad social and political ferment of the 1960s; the other a critique of what the aesthetics of modernism had become. The political movement fueled a professional critique that had started independently before the late 1960s. In this composite movement, the definition of the object of criticism determined to a large extent where the challenge would be headed.

Briefly, the different phases of the postmodern challenge were as follows. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the concern of younger architects with their role in society transpired in architectural discourse about form and meaning. In the late 1970s and the 1980s, as the political movement ebbed, discourse veered toward transforming architectural objects; it seemed crucial then to obtain architectural legitimacy for diverse kinds of professional realizations. In other words, the challengers by and large kept themselves within an established professional identity, limiting their defiance to challenging the boundaries of legitimate professional discourse. As defiance ebbed and business more or less as usual returned in the late 1980s, the social and formal dimensions of architecture tended once more to diverge. Because of the legitimacy that had been gained for projects of all sorts, small-scale architectural craftsmanship emerged as a credible alternative to subordinating one's talents to power. Let us consider how these elite designers see different moments of this passage.

Tom Wolfe has flippantly dismissed the barren functionalist vocabulary of the once hegemonic International Style as "workers' housing."[10] Yet its

most visible embodiments were quite the opposite: the towers that changed streets and urban skylines in the United States and the world during the long boom that ended in the mid-1970s. A younger generation of architects, having as yet no vested interest in the design of downtown office buildings, could afford to attack simultaneously the architectural language and its foremost type of building. Corporate architects could not.

We understand, then, why Bunshaft's formalist defense completely avoids the issue of building types and also why Graham concedes the negative urban effects of freestanding monoliths without questioning their presence or functions; why, in fact, he dissolves objections to the skyscraper's program into a technocratic ideology about the physical "building of cities." We can imagine younger architects responding to Graham that suburban houses for the rich are distinctly less harmful than crowding the world with office buildings, even though they may be just as inane for society and the collective welfare.

Tigerman's combined reference to Vietnam and Las Vegas is more perplexing. First, the barrenness and brutal antiurbanism of International Style skyscrapers had capitalist sponsors. A government fully identified with capitalist interests was waging a savage war against Vietnam, and losing it. It was easy to defy the whole by challenging its parts. Metonymy was a major rhetorical recourse, not of architecture only but of most disciplinary challenges in the 1960s.