Three—

Maturity

The Berlin Secession

Corinth's rise to fame in Berlin was closely linked to the growing importance of the Berlin Secession as the strongest and most influential artists' association in Germany. Within a few years of its founding the group's exhibitions eclipsed the much larger shows at the Berlin Glass Palace by appealing to liberal and well-to-do intellectual circles receptive not only to new developments in German art but also to new impulses from abroad. The second exhibition, in May 1900, which paid special tribute to Hans von Marées, the nineteenth-century German painter whose experiments with problems of pictorial structure have since been recognized as milestones in the evolution of modern art and aesthetics, included works by no fewer than forty-four foreigners, among them Pissarro, Monet, Renoir, Rodin, and Whistler. In 1901 the French Impressionists were again well represented, as was van Gogh. Manet made his belated debut in 1902, the year that Wassily Kandinsky exhibited with the Berlin Secession for the first time and Edvard Munch was represented by twenty-eight pictures from his Frieze of Life cycle. Toulouse-Lautrec and Cézanne dominated the exhibition in 1903. The names Max Beckmann, Hans Purrmann, and Alexey von Jawlensky were added to the Secession's membership roll in 1904.

In 1902 the Berlin Secession held the first of its annual winter exhibitions devoted exclusively to the graphic arts, an unusual undertaking at the time. These black-and-white exhibitions, as they were called, featured in quick succession the work of such diverse artists as Käthe Kollwitz and Aubrey Beardsley. Emil Nolde, Kandinsky, and Lyonel Feininger participated in the graphic show of 1903. In the winter of 1908 the exhibition was highlighted by a selection of drawings by the early nineteenth-century Berlin realist Franz Krüger and prints by the young men of Die Brücke: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Max Pechstein. By 1908 Nolde, Kandinsky, Feininger, and Ernst Barlach had become members of the Berlin Secession. By 1911 the organization had shown the work of virtually every leading artist of the then burgeoning movements of Expressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism.[1]

In its efforts to introduce modern art to Berlin, the Secession found continued and energetic support in Bruno and Paul Cassirer. The two dissolved their partnership in 1901 and henceforth each worked independently. Bruno Cassirer took over the publishing firm and in 1902 founded the journal Kunst und Künstler , which developed into Germany's leading art periodical under the editorship first of Emil Heilbut and then of Karl Scheffler. The journal also became an eloquent proponent of the Berlin Secession. Until shortly after the First World War, Bruno Cassirer continued to publish important books on art and aesthetics as well as illustrated books still acclaimed for their handsome typography and design. Paul Cassirer, in turn, assumed responsibility for the Cassirer gallery and remained the sole business manager of the Berlin Secession. After 1908 he reentered the publishing business. In addition to the Paul Cassirer Verlag, he started the Pan Presse, which specialized in luxury editions of books, graphics, and print portfolios; and he created Pan , a cultural and political periodical named for the journal founded in 1895 by Julius Meier-Graefe and his two friends the poets Otto Julius Bierbaum and Richard Dehmel. All of these operations came to be closely associated with the Berlin Secession.

In his gallery, Paul Cassirer mounted on the average six major exhibitions a year. He regularly featured the leading exponents of the Berlin Secession and reinforced the organization's international outlook by opening his gallery to artists from abroad. In 1903 he showed works by Munch, Bonnard, Vuillard, Degas, and Monet, and with an exhibition of paintings by El Greco he revived interest in a master whose idiosyncratic style was being revalued as younger artists pursued an analogously expressive use of color and form. In the spring of 1904 Cassirer held the first major exhibition in Germany of oils and watercolors by Cézanne. In 1908 he showed paintings by van Gogh and Jawlensky as well as a series of landscapes by Christian Rohlfs; in 1910 he organized the first major exhibition of works by Kokoschka. Soon Paul Cassirer's salon was known as the country's leading gallery of modern art and the main source for French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works for museums, galleries, and private collections in central Europe.

Remarkably courageous, the Berlin Secession and Paul Cassirer opposed not only the official Berlin art world, embodied in Anton von Werner and his fellow academicians, but also the aesthetic precepts espoused by the political regime. Indeed, the imperial court took more than a passing interest in such matters. Wilhelm II liked to think of himself as a monarch under whom the arts could prosper. He himself painted, designed monuments, composed music, and occasionally even directed rehearsals at the Royal Opera and the

Royal Theater. His taste was conservative, and—chauvinistic to the core—he delighted in any artistic effort celebrating the achievements of the house of Brandenburg-Prussia. A comment in the conservative Reichsbote of February 14, 1897, in which the "ridiculous fad for the foreign" is thoroughly disparaged, aptly echoes his suspicion of any cultural influences from abroad: "The wealthy, educated circles in Germany still have to understand far more clearly than they do at present that they owe it to the Fatherland and to their honor to favor German art and thus spur it on to great achievements."[2]

Wilhelm II even liked to foster the illusion that Germany had been appointed the sole guardian of Western civilization. "To us Germans, great ideals, more or less lost to other peoples, have become permanent possessions,"[3] he proclaimed in a speech of September 18, 1901, inaugurating the Siegesallee. This broad avenue, which leads through the Berlin Tiergarten to the Brandenburg Gate, was lined with thirty-two larger-than-life-size statues of his Hohenzollern forebears carved in Carrara marble under the direction of Reinhold Begas. He envisioned the lower classes, after a day's hard work, uplifted by art, by the contemplation of beauty and the ideal. But he reviled all art that—in his view—descended to the gutter (he called it Rinnsteinkunst ) by depicting misery as more wretched than it really is. A number of writers and artists had by this time already felt the sting of his criticism. When Gerhart Hauptmann's working class drama Die Weber opened on September 25, 1894, at the Deutsches Theater, Wilhelm II registered his displeasure by canceling his subscription to the royal box. When Hauptmann was subsequently recommended for the prestigious Schiller Prize in 1896, the kaiser decided to grant the award to Ernst von Waldenbruch, his own favorite, who wrote historical plays in the manner of Schiller's Wilhelm Tell . Moreover, the emperor vetoed the gold medal proposed in 1898 for Käthe Kollwitz in recognition of her print cycle The Weavers' Revolt (1893–1897), a work inspired by Hauptmann's drama. Regis voluntas suprema lex was one of his favorite expressions; and there was no doubt that he meant what he said.[4]

By deliberately dissociating itself from the Glass Palace, an institution that enjoyed the emperor's personal patronage, the Berlin Secession aroused the kaiser's annoyance. By showing, especially in the early exhibitions, works by Liebermann and Uhde that, though by no means anarchistic, dealt with working-class themes, the Secession seemed to encourage the kind of art Wilhelm II dismissed as Rinnsteinkunst . And since the work of several Secessionists so obviously tended toward Impressionism, whose French origins were known even in imperial circles, the Secession quite openly defied the kaiser's claim that only a genuinely German art had value. The astonishing

success and popularity of the Berlin Secession in the face of such opposition can be explained partly by the political and ideological dimensions that inevitably colored the cultural life of both the German capital and the country as a whole at this time of rising nationalism. As Peter Paret has observed, the opening exhibition of the Berlin Secession resembled "an early election victory by a new political party, which arouses strong positive and negative reactions merely by the fact of its existence."[5]

Lovis Corinth profited immensely from his association with the Berlin Secession. By 1902 he was a member of the executive committee and had signed a contract with the Cassirer Gallery. After Paul Cassirer started up his press, he published two books by the painter: a teaching manual, Das Erlernen der Malerei (1908), and a biography of Walter Leistikow (1910). Corinth also illustrated for Paul Cassirer the Book of Judith (1910; Schw. L54) and the Song of Songs (1911; Schw. L82), both published with the Pan Presse imprint. In 1909 Bruno Cassirer's press brought out Corinth's autobiographical account Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben .

From a technical point of view, Corinth's new environment had a liberating effect on his style. As a result of his growing familiarity with French Impressionism, his brushwork became more vibrant, his colors lighter. The same development can be seen in the work of Max Slevogt who, like Corinth, had been a member of the Munich Secession and its rebellious offshoot the Free Association. Slevogt, too, was elected to the executive committee of the Berlin Secession in 1902 and signed a contract with Paul Cassirer. Prior to the arrival of Slevogt and Corinth in Berlin, Max Liebermann had been the most potent artistic force in the Secession. After 1901 the leadership of all three painters was recognized.

A School for Women Painters: Charlotte Berend

During the ensuing years Corinth devoted much of his energy to teaching. On October 15, 1901, he opened a private school in his studio on Klopstockstrasse. Like Stauffer-Bern's enterprise earlier, this was planned as a school for women painters, although a small contingent of men rounded out the student body from the very beginning. From 1904 on Corinth taught his students in a second studio he rented on nearby Händelstrasse. He also taught for many years in the school of the sculptor Arthur Lewin-Funcke, which was modeled on the Académie Julian. Only a few of Corinth's students have found a place in the history of art. They include Oskar Moll, Ewald Mataré, and August Macke, all of whom, however, ultimately evolved an art independent of Corinth's example.

Corinth once remarked that the money he had earned from teaching had made him a "well-to-do man."[6] But financial considerations were not the reason that he attended conscientiously to his students for so many years, offering firm but encouraging counsel, impatient only toward those who sought to impress him with technical virtuosity or willfully nurtured stylistic peculiarities.[7] He felt "called" to be a teacher.[8] Whatever he had learned at the academies in Königsberg and Munich and at the Académie Julian in Paris, he now wished to pass on to a younger generation of painters, not only directly but also indirectly, by way of the teaching manual he published in 1908. Corinth in fact looked on teaching as a learning process that further clarified his approach to his own art. As he wrote in his autobiography: "Only now did I grasp many things my teachers had tried to make me understand earlier. To be constantly surrounded by models, moreover, is highly instructive. I suggest that every artist, by all means, seek his final perfection through teaching."[9]

Corinth's School for Women Painters brought him face-to-face with the person who was to play the most decisive role in his subsequent professional and personal life: Charlotte Berend, one of the first students to come knocking at the door of his studio in October 1901. The daughter of a well-to-do cotton importer, Charlotte Berend managed to combine the social conventions of her upbringing with a generous and outgoing spirit. She was twenty-one when she first came to study with Corinth. At least initially the painter must have represented for her something of a father figure, for at forty-three he was only five years younger than her own mother. Despite her youth, however, Charlotte Berend soon developed an intuitive grasp of Corinth's character. Her initiative, resourcefulness, and sensitivity toward his art quickly made her his favorite pupil. In a matter of months their relationship blossomed into mutual affection. They spent a good part of the year 1902 traveling together: they went to Horst on the Pomeranian seacoast in the summer and in early fall to Munich and Tutzing. On March 26 the following year they were married in Berlin.

Nothing is known about Corinth's earlier relationships with women, but it is safe to assume that these were at best casual affairs that meant little to him. Charlotte Berend, as a fellow painter, brought to her role as lover and wife a keen awareness and understanding of his needs as an artist. She was unfailingly supportive whenever he expressed the slightest doubt in his work and knew just how to coax him if the occasion demanded. Corinth, who had spent his childhood in a household devoid of domestic warmth and who as a bachelor had experienced that warmth only in the homes of others, found emotional stability through his marriage to Charlotte Berend.

Corinth's son Thomas was born on October 13, 1904, his daughter Wilhelmine on June 13, 1909, one month before the painter's fifty-first birthday. Charlotte Berend provided the pivotal link in this home of three generations, and her central role in Corinth's life is amply documented in his work. Not only are there many portraits of her, but she also appears anonymously in pictures of nudes, in interiors, and in figure compositions. Many of the paintings and drawings Corinth made of his wife had their origin in a spontaneous situation she herself created: a new dress or a shawl, her way of twirling a parasol or adjusting a garter, or simply a clownish face made in jest. It is no exaggeration to suggest that by her gentle guidance Charlotte Berend single-handedly enriched Corinth's perception of human nature and unlocked in him resources that were to bear ample fruit in the years to come.

Early Portraits of Charlotte Berend

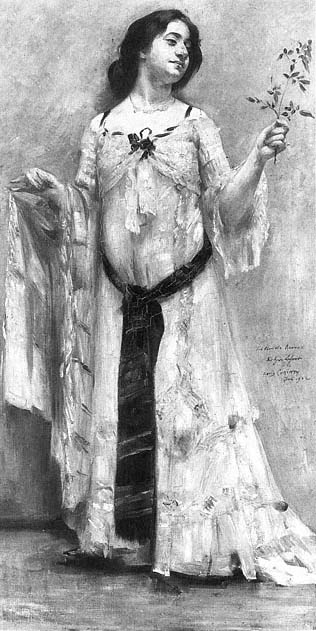

Corinth's first portrait of Charlotte Berend (Fig. 80) is dated July 1, 1902. The painting was a gift to the student; it bears a dedicatory inscription to "Frl. Charlotte Berend" and is signed "Herr Lehrer Lovis Corinth." The formal tone of the inscription is matched by the painter's conception, which stresses the conventional, representative qualities common to Corinth's full-length portraits of this type. As in the portraits of 1900 of Bianca Israel (B.-C. 175) and Margarethe Hauptmann (B.-C. 196) and in the portrait of Frau Simon of 1901 (B.-C. 197), emphasis is on the handsome dress, which is set off to particular advantage by the shallow, undifferentiated ground. In contrast to the earlier portraits, however, Corinth gave the painting an allegorical dimension by adding the twig of rose leaves that Charlotte Berend holds. Read in conjunction with her white dress, it alludes to her youth and innocence. As he came to recognize the special attraction Charlotte Berend had for him, Corinth was surely troubled by their great difference in age; with the allegorical allusion he may have acknowledged a growing sympathy he was not yet prepared to state. Charlotte Berend, in turn, perhaps unsure of her feelings toward Corinth, took refuge in a staged and mannered pose that allowed her to maintain psychological distance. That both teacher and student needed the shield of some playful subterfuge to hide their emotions is confirmed by an episode that took place while Corinth was at work on the portrait. The package in which Charlotte Berend had brought the white dress to Corinth's studio also contained several items she had worn earlier to a ball: a black scarf, a fan, and a mask. One day, when Corinth asked her about the other contents of the

Figure 80

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Charlotte Berend in a

White Dress , 1902. Oil on canvas, 105 × 54 cm, B.-C. 241.

Berlin Museum, Berlin.

Photo: Hans-Joachim Bartsch.

package, she put on the scarf and the mask and fanned herself coquettishly to show him how she had looked at the ball. Corinth was so enthralled that he painted her in this disguise as soon as the first portrait was finished.[10] This second portrait (B.-C. 236) is astonishingly free in execution; in gesture and posture it conveys Charlotte's vivacious temperament far more than the first. But her thoughts remain hidden by the mask.

During the weeks the two spent together at the Pomeranian seacoast, Corinth painted Charlotte Berend four times. Only one of these pictures (Fig. 81) is a portrait in the conventional sense; it is also the most intimate of the four paintings and a testimony to the affection and trust that by then had developed between teacher and student. As in the first portrait from Berlin, the pictorial structure is simple. Only a corner of the window in the upper left enlivens the background. The wildflowers in the glass on the windowsill echo the colored floral pattern of Charlotte's black dress. Her posture is graceful but without affectation, and her open gaze meets the painter's own with sympathy and understanding. Corinth underscored his affection by inscribing the words "Mein Petermannchen" in mirror writing on the arm of the chair.[11] Charlotte Berend had only recently told him how several years earlier, while on vacation with her parents and sister, she had managed to ward off the advances of a snobbish young suitor by pretending that she was not at all the bourgeois girl he wished to court but rather a Gypsy by birth, a foundling and adopted child, whose real parents, members of the tribe Petermann, had abandoned her in infancy. Petermann and the diminutive Petermannchen (sometimes emphasized for greater effect as Petermannchenchen) were henceforth Corinth's names of endearment for Charlotte.[12]

An early pencil drawing of Charlotte Berend (Fig. 82) dates from the trip the lovers took to the Starnberger See in the fall of 1902. Charlotte, who had unexpectedly fallen ill, lies asleep at the couple's inn at Tutzing. The drawing bears eloquent witness to Corinth's empathy. The face is lovingly modeled; only at the periphery of the image does the shading give way to a more summary rendering. The conception recalls the portrait of Luise Halbe from 1898 (see Fig. 73), and the drawing, with an independence of expression previously reserved for Corinth's work in oil, signals a new role for his graphic works. This is seen even more clearly if the drawing is compared to the oil sketch (B.-C. 259) Corinth completed in the course of his vigil at Charlotte's bedside. The oil sketch retains all the freshness and spontaneity of the drawing, making the latter, by implication, an autonomous work of art.[13] Henceforth Corinth's drawings frequently surpassed his paintings in their harmony of content and form.

Figure 81

Lovis Corinth, Petermannchen , 1902.

Oil on canvas, 119 × 95 cm, B.-C. 240.

Private collection.

Figure 82

Lovis Corinth, Charlotte Berend Asleep ,

1902. Pencil, 35.2 × 34.3 cm.

Collection, The Museum of

Modern Art, New York.

The Joan and Lester Avnet Collection.

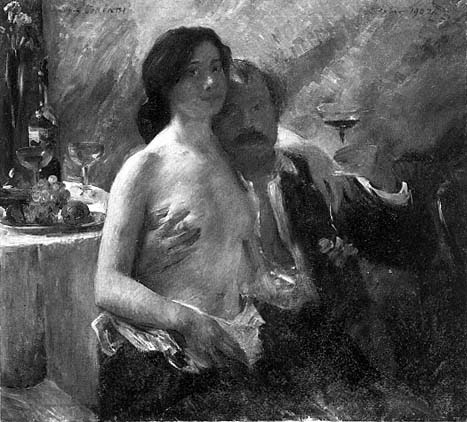

Figure 83

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with Charlotte Berend and Champagne Glass , 1902.

Oil on canvas, 97 × 107 cm, B.-C. 234. Auctioned July 3, 1979, at Christie's,

London; present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Christie's-Artothek.

Double Portraits with Charlotte Berend

Charlotte Berend's expanded role in Corinth's life is documented by several paintings from 1902 for which she posed in the nude. They include the large double portrait (Fig. 83) painted in October after the lovers' return from Bavaria. An immense gulf separates this painting from the preceding double portrait (see Fig. 79) in which Corinth, assured in his professional calling, had depicted himself at work in the company of a young model. Primacy of place now belongs to Charlotte Berend. Her body, naked to just below the waist, is fully illuminated, and she engages the viewer's attention with her open gaze. She holds a flower in her left hand, again most likely in symbolic allusion to her youth. Corinth himself looks younger and trimmer than in any of the self-portraits from the 1890s. Supporting Charlotte on his knee, he raises a glass in celebration of their love. According to Charlotte Berend, the idea for the double portrait originated with Corinth himself, and the execution of the painting proceeded as swiftly as the energetic brushstrokes suggest:

As he began to paint, it seemed to me that I had never known him like this. He rejoiced as he worked . . . and shouted: "How happy this makes me. . . . Just look, the picture is painting itself of its own accord. Come, let's take a short break! I'm going to have some wine, and you have some too.". . . He laughed. "Cheers, my Petermannchen, and now back to work!"[14]

The conception of the painting was no doubt inspired by the famous double portrait in Dresden in which Rembrandt depicted himself with his wife Saskia on his knee. Rembrandt, however, moralized in the manner characteristic of similar seventeenth-century Dutch pictures, painting himself in the guise of the Prodigal Son, warning against frivolous pleasures while ostensibly delighting in them. Although Corinth's painting, too, transcends the specific experience of the two figures, vibrant and tactile brushwork transforms it into an unequivocal evocation of the joy of life.

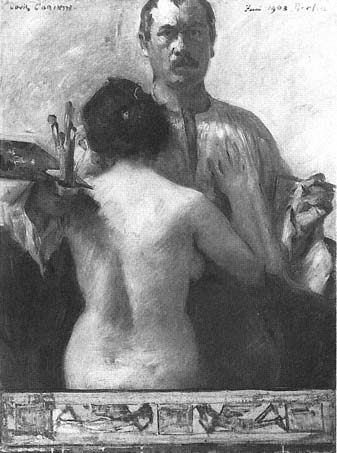

In June 1903, about three months after his marriage to Charlotte Berend, Corinth returned to the subject of the double portrait in a considerably modified form (Fig. 84). Although Charlotte again occupies the frontal plane of the picture, the painter dominates it, showing himself with the tools of his profession recording the image he sees before him. There is no longer any hint of apprehension about Charlotte's youth, and the intoxication of courtship has given way to a new self-assurance. Corinth has clearly regained control of his emotional life. He confronts himself boldly; Charlotte, her back toward the

Figure 84

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with Model , 1903. Oil on canvas,

121 × 89 cm, B.-C. 256. Kunsthaus Zurich (1951/17).

viewer, stands close to the painter, protected by his arms, but also shielding him, her gesture at once suppliant and supportive. The emotional equilibrium the couple has achieved is echoed in the balanced pictorial structure. The two standing figures emphasize the central vertical axis of the composition; the painter's hands accentuate the corresponding horizontal division. A few years later Corinth reproduced a photograph of this painting in his teaching manual as an example of how to distribute the structural elements in a pictorial field so as to achieve a well-thought-out, balanced composition.[15]

Figure 85

Lovis Corinth, Charlotte Berend in a Deck Chair , 1904. Pastel

and charcoal on gray paper, 49.5 × 60.0 cm. Westfälisches

Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte/Westfälischer

Kunstverein, Münster (939 WKV).

Charlotte Berend as Mother and Other Family Portraits

The months just before the birth of their two children were for Corinth and his wife a period of particularly close communion. In the charcoal and pastel drawing of July 31, 1904 (Fig. 85) Charlotte is six months pregnant. Her intent look no doubt reflects Corinth's own anxiety as much as it expresses her need for affection and security. Though contemporary with the painting In a Deck Chair (B.-C. 285), the drawing is not a preliminary study for the picture but, like the earlier pencil sketch from Tutzing (see Fig. 82), another autonomous document of the spiritual bond between artist and model.

Corinth was spellbound by the processes of new life as they were revealed to him in the course of his wife's pregnancies. In addition to the picture from July 1904, he painted Charlotte five days before the birth of Thomas (B.-C. 281) and twice in 1909 as she awaited the birth of Wilhelmine. In conception each of these paintings is personal, but the 1909 paintings also speak of Corinth's need to universalize the experience of Charlotte's motherhood. One shows her nude (B.-C. 401); the other (see Plate 14) depicts her seated in Corinth's studio, her breasts partly exposed. Only her posture alludes to her pregnancy. The general disposition of the figure is anticipated in both a canvas (B.-C. 354) and a drypoint (Schw. 27) from 1908 depicting Charlotte seated by a window. But now no environmental allusions interfere with the subject. The subdued colorism reinforces the simple pictorial structure. As in the drawing from July 1904, Charlotte's expression mirrors both trust and devotion. While the painting has rightly been compared to Wilhelm Leibl's portrait of Mina Gedon when she was expecting a child,[16] Corinth himself invited another challenging comparison when he borrowed the title of the picture, Donna gravida , from Raphael's panel in the Pitti Palace.

Corinth brought the same empathy with which he had observed his wife during her months of pregnancy to the theme of mother and child. Except for the rather conventional double portrait from 1901 of Gertrud Mainzer and her daughter Lucy (B.-C. 223), the subject does not occur in his earlier work. Only with the birth of his own children did he begin to fathom the bond of parental affection. Whereas Frau Mainzer poses proudly with her daughter in the comfort of her well-appointed Berlin home, the real subject of Corinth's first painting of Charlotte and Thomas (Fig. 86), completed between April and May 1905, is the loving interaction of mother and son. Charlotte holds the boy on her lap, gently directing his attention to the painter, who is thus allowed to share in the spirit that unites the two. Though barefoot, Charlotte wears a splendid dress that lends the painting a festive air reminiscent of Rubens's double portrait in the Alte Pinakothek of Helena Fourment and her son Frans, a picture that may well have influenced Corinth's conception. Indeed, Rubens's unusual group of paintings of his two wives, Isabella Brant and Helena Fourment, and the Rubens children surely furnished the prototypes for Corinth's own family portraits. More intimate than the picture with Thomas is the one Corinth painted in June 1909 (B.-C. 391), four days after the birth of Wilhelmine. As Charlotte nurses the infant, her affection expresses itself eloquently in her tender gaze and protective gesture. The extreme close-up view is no doubt a measure of Corinth's empathic response to the domestic scene.

Figure 86

Lovis Corinth, Mother and Child , 1905.

Oil on canvas, 127 × 107 cm, B.-C. 312.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Marburg/Art Resource, New York.

Figure 87

Lovis Corinth, Mother and Child , 1906. Oil on canvas,

80 × 95 cm, B.-C. 326.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

In addition to several portraits of young Thomas (B.-C. 278, 311, 374) and three more double portraits of Charlotte with Wilhelmine, Thomas, and again Wilhelmine (B.-C. 392, 393, 456), there are several works that invest the subject of mother and child with a more general meaning. In a painting of 1906 (Fig. 87) both Charlotte and Thomas are shown in prototypical nudity. Charlotte reclines on a couch and turns, smiling toward the boy. The flower she holds

Figure 88

Paula Modersohn-Becker,

Kneeling Mother and Child ,

1907. Oil on canvas, 113 × 74 cm.

Staatliche Museen Preussischer

Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie,

Berlin (West) (NG 7/85).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

and the bouquet in the upper right corner of the composition underscore the allusion to fecundity and new life. Unfortunately, the painting is burdened by the implicit erotic appeal typical of Corinth's mature depictions of the female nude and remains much too close to the model to be convincing in generalized terms. The same physiognomic veracity and forced expression greatly diminish the effect of Motherly Love (B.-C. 457), another painting of Charlotte and Thomas, from 1911. The weakness of Corinth's solution in these pictures is especially apparent in comparison with Paula Modersohn-Becker's symbolic representations of about the same time (Fig. 88). Under the influence of van Gogh, Gauguin, and several primitive and antique sources Modersohn-Becker had evolved a simplified and monumental pictorial language with which to express convincingly the eternal truths of womanhood. Her anonymous mothers, painted in flat, warm colors and heavy, volumetric shapes, evoke the generative processes of life.

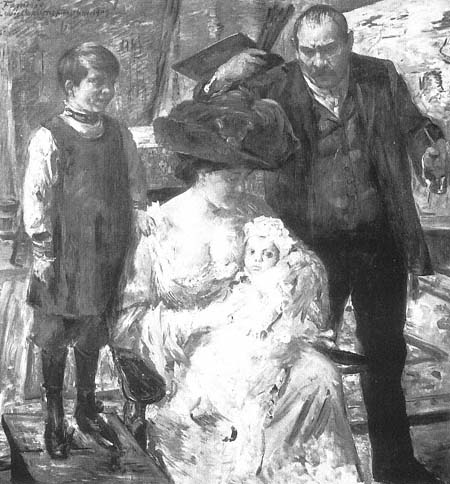

Corinth's pictures of his young family culminated in the group portrait (Fig. 89) he painted in November 1909. According to Charlotte Berend, he prepared the painting with great care. He selected a canvas that had exactly the same dimensions as the large mirror he was using for the occasion, and he insisted that the four figures pose together as a group rather than individually. While painting, Corinth kept moving back and forth between the canvas and his place in the composition.[17] The arrangement of the figures parallel to the picture plane might easily have resulted in a monotonous group-

Figure 89

Lovis Corinth, The Artist and His Family , 1909. Oil on canvas, 175 × 166 cm,

B.-C. IV. Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 7/1918).

ing had Corinth not enlivened the background with a variety of colors, textures, and shapes and allowed each figure a considerable measure of independence. The painting is indeed a study in contrasts skillfully reconciled. Thomas, who had just turned five, stands on a stool at the left and places one hand on his mother's shoulder. His attention is focused on the canvas on which Corinth is at work. Charlotte Berend, wearing a luxurious dress and a large hat, is seated in the middle, looking down at five-month-old Wilhelmine in her lap. Charlotte is the physical and psychological center of the painting, her role as mother underscored by her intimate contact with both children. Corinth shows himself in the act of painting and thus partakes of the family idyll primarily as an observer. The scattered attention of the various figures finally comes to rest on Wilhelmine, the only one in the group to look straight into the mirror. Corinth also emphasized the relationship of the figures coloristically. White is distributed so as to predominate in Charlotte and Wilhelmine. Shades of brown link the painter and his son. Charlotte, however, shares in both colors to a significant degree and thus further unifies the family gathered around her.

Portraits of Friends and Other Artists

Except for the works that originated in the intimacy of his family, Corinth painted relatively few portraits between 1902 and 1910. Although the prospect of lucrative portrait commissions had helped persuade him to settle in Berlin, the market for portraits of members of Berlin society close to the Secession turned out to be dominated by Liebermann and Slevogt, and Corinth apparently decided to carve out a special niche for himself by channeling his creative energy into figure compositions instead. Moreover, potential patrons may have thought Corinth uncongenial as a painter, for his portraits did not necessarily flatter, and he approached pictorial problems in decidedly unorthodox ways. He was freer to follow these inclinations when he painted a portrait on his own initiative or, as in the group portrait of the Berlin painter Fritz Rumpf's family (see Plate 15), when he was assured of the client's sympathy and understanding.

This particular painting is as much a painting of light as a representation of individual likenesses. In fact, it can be argued that the painting achieves the character of a group portrait only through the independent agent of light. A comparison in this regard with the painting of the Johannes Lodge (see Fig. 74) is instructive, especially since the two compositions are similar, the figures in

both works having been arranged in two rows parallel to the picture plane. The earlier painting depicts twelve distinct individuals independent of one another; in the 1901 work Corinth managed to unify the group in a way that expresses something about the figures' family relationships. Indeed, the painting is the precursor of the large group portrait he painted of his own family in 1909. Margarethe Rumpf and her six children are seated in the elevated alcove of the family's dining room before a leaded window. The figures are illuminated from several directions and, depending on the strength of the light that envelops them, assert their individuality within the group. Frau Rumpf is seated at the far right of the second row. Her features are the most clearly defined, and she engages the viewer's attention by her gaze. The faces of the boy and the girl at the extreme left are shown in profile silhouetted against the bright window, a view that clearly reveals their resemblance to their mother. Corinth subordinated the younger children to the form-dissolving effects of light according to the development of their features, concentrating the light on the two youngest and enhancing this part of the canvas with special coloristic appeal. The pink dress of the curly-haired boy in the center is brought into harmony with the bright red of his socks and intensified by the adjacent tones of white, orange, and olive green. As in Rembrandt's famous family portrait in Braunschweig, the splendor of the colors transforms the image into something immaterial. The vibrant brushstrokes, too, suggest more than they describe. As they unify the group, they carry a meaning in human terms that transcends the specific character and situation of the individuals portrayed.

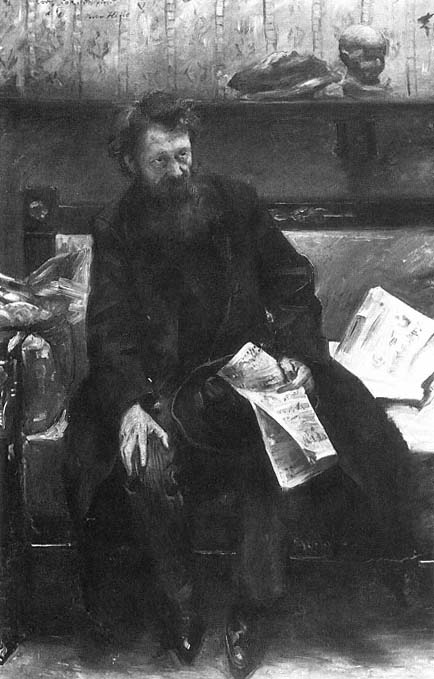

When he painted the portrait of the poet Peter Hille (1854–1904) (Fig. 90), Corinth found himself face-to-face with an incorrigible eccentric, and he responded with a character study that, while less subtle, equals in perception the portrait of Eduard von Keyserling (see Plate 13). Hille's shabby appearance and unconventional demeanor made him a curious sight in the bourgeois milieu of the German capital. Yet he was tolerated in the city's intellectual and artistic circles, where he showed up unannounced, carrying a large satchel filled with voided streetcar tickets and the other scraps of paper on which he scribbled his poems and epigrams. Aversion to discipline and disregard for bourgeois conventions were among Hille's character traits, along with an almost childlike innocence that accounted for much of his popularity. Hille, a native of Erwitzen, near Paderborn, rebelled early against the strictures of family life. After working briefly in the late 1870s in Bremen, on the editorial staff of the Deutsche Monatsblätter and the Bremen Tageblatt , he tried to establish himself as an independent writer in Leipzig. When this effort failed, he went to London to study in the library of the British Museum but

Figure 90

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Poet Peter Hille , 1902.

Oil on canvas, 190 × 120 cm, B.-C. 237.

Kunsthalle Bremen.

spent most of his time from 1880 to 1882 in the slums of Whitechapel. He subsequently traveled, mostly on foot, as far as Italy and Hungary. While serving as the manager of a small troupe of itinerant actors in Holland, he squandered what remained of a small inheritance from his mother. Although Hille gained recognition in the late 1880s for his novel Der Sozialist (1887), he is remembered now more for his Bohemian life-style than his literary output. Always neglectful of his health, he died of a lung hemorrhage in Berlin at the age of forty-nine.

Corinth has spoken of the circumstances that led to the Hille portrait. When he mentioned to Peter Behrens that he was in search of an interesting-looking model, Behrens called Hille to his attention, warning him that the talkative poet was wont to make interminable visits. When Hille came to call on Corinth and began to remove his outer garments, the painter, remembering Behrens's words of caution, quickly told him: "Don't bother. I'll paint you just the way you are."[18] In the large, life-size portrait Peter Hille is indeed still dressed in his overcoat, his hat on his knee. But the anecdote alone hardly explains the painter's conception; only deliberate artistic decisions could have produced so apt a characterization. Everything about the sitter speaks of his restless nature—his fidgety posture, the folds of his coat, and the crumpled hat and sheets of newspaper—and Hille imparts this restlessness to his immediate surroundings, as in the squashed-down pillow at the left. He hovers on the edge of the sofa, his feet hardly seeming to touch the floor, and his gaze is turned upward as if something had suddenly caught his attention. The unusually well-ordered pictorial structure accentuates the disquiet of his bearing. The lines of the sofa and the shelf above it divide the canvas horizontally into parallel planes, providing a sense of stability at odds with the poet's restive figure. The conch shell and the small bust—perennial appurtenances of bourgeois culture—on the shelf above him further signify a world in which Peter Hille is no more than a peripatetic guest.

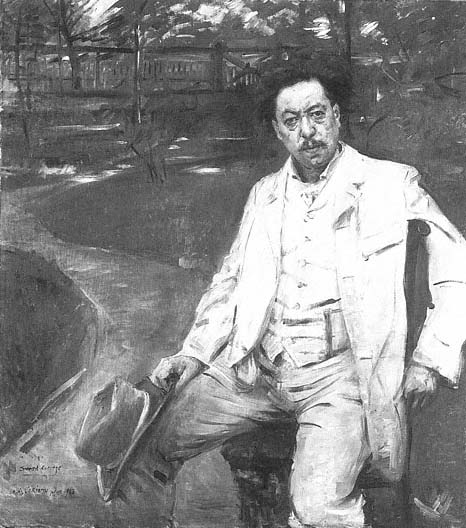

The otherwise very different portrait of the pianist Conrad Ansorge (1862–1930) is equally perceptive (Fig. 91). Here again Corinth set out to fathom the enigmatic inner life of a creative individual, and his approach to the task is as unconventional as it is successful. One might expect, for instance, to see Ansorge at the piano or, possibly, in the privacy of his study. Instead Corinth painted the musician outdoors, seated in the garden as if relaxing after a walk. What is more, Corinth divided the pictorial field so as to give equal physical weight to the sitter and the landscape. Coloristically, too, these parts of the composition balance, the white of Ansorge's suit holding its own against the green and earth tones of the garden. From an expressive point of view, how-

Figure 91

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Pianist Conrad Ansorge , 1903. Oil on canvas,

141 × 125 cm, B.-C. 264. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (FH 247).

ever, the musician's spiritual presence dominates the painting. The fence in the background and the vertical axis of the chair lead resolutely to Ansorge's head, which forms the psychological, if not the physical, center of the composition. Even the outdoor light is not allowed to interfere with the modeling of the thoughtful face, encroaching on the sitter only in the quick brush-strokes with which Corinth accented the folds of the suit. Whereas the portraits of Keyserling and Hille bear witness to precarious physical and emotional states, the portrait of Ansorge is the very image of equanimity.

Ansorge, who looks older than his forty-one years, was just beginning his great international career. A native of Silesia, he had studied with Franz Liszt and in 1887 completed a successful first tour of the North American continent. He made his home in Berlin in 1895 but traveled all over Europe and South America giving concerts and recitals. He was especially acclaimed for his interpretation of the great Romantics, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, and Chopin; but he was also a keen champion of the works of contemporary composers and himself set to music texts by Stefan George, Alfred Mombert, and Stanislaw Przybyzewski. Though famous for his command of the keyboard, Ansorge despised the pursuit of virtuosity for its own sake and distinguished himself among the pianists of his generation by faithfully adhering to a composer's intentions. Sensitivity and intelligence were the hallmarks of his playing and earned him the love and respect of his many students. Corinth, too, perceived the spiritual side of Ansorge as his very essence and underscored it in the portrait.

The Mature Figure Compositions

Although Corinth exhibited several of his portraits—and some, such as the portrait of Peter Hille, elicited much favorable comment—he solidified his reputation in Berlin on the basis of his figure compositions, the works with which he asserted his independence among the leaders of the Berlin Secession. For Liebermann, by comparison, who had long abandoned his earlier aspirations of becoming a history painter, subject matter in painting mattered little or mattered only insofar as it related to purely artistic matters. To him "a well-painted turnip," as he put it, was "as good as a well-painted Madonna."[19] Corinth, in contrast, owed his real recognition to such weighty themes as the Pietà and the Deposition and to his provocative Salome and thus had every reason to believe that other paintings like these would continue to attract wide public attention.

The figure compositions from Corinth's early years in Berlin are for the most part large in scale and feature many characters in complicated foreshortened postures. Because the pictures, like the Tragicomedies cycle, explore parodistic elements, they often created something of a spectacle at the exhibitions of the Berlin Secession. The general public greeted them enthusiastically, but critical reaction was usually mixed. Gustav Pauli called Corinth's figure compositions "fatal aberrations of a brilliant technician."[20] Meier-Graefe found in them a gap, difficult to bridge, between content and form. "From many a painting by Lovis Corinth," he observed caustically, "emanates the physical potency of animals in heat. Sometimes one is tempted not to look for fear of having to smell what one sees. Tender souls recoil horror-struck. Painters rejoice."[21] Both Pauli and Meier-Graefe judged Corinth's figure compositions from a pro-Impressionist bias, and in the context of the painter's late works these pictures indeed appear not only superficial but often in bad taste as well. Nonetheless they are important for a full understanding of Corinth's development, for only in relation to them can his final achievement as an artist be appropriately measured.

Naturally, Corinth himself thought highly of these pictures. Summing up his activity during his early years in Berlin, he singled out several of them, convinced that in time they would be counted among his best works.[22] Critical perception and the high quality of Corinth's later output have contradicted his own assessment; yet the original success of his figure compositions affected even the most unsuspecting of his fellow Secessionists. Several melodramatic compositions by Slevogt, such as Samson Blinded (1906; private collection), The Massacre of the Innocents (1907), Rape (1905), Battle of Titans (1907) (all in the Niedersächsische Landesgalerie, Hannover), and Knight and Women (1902; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister), as well as Liebermann's Samson and Delilah (1902; Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt), their subjects by then so at odds with those of other mature works by both these painters, illustrate how persuasive the popularity of Corinth's figure compositions could be. The effect of Corinth's figure compositions on younger artists like Max Beckmann was more lasting. Indeed, Corinth to a large extent passed on to Beckmann the nineteenth-century tradition of the grand theme.[23] It is difficult, if not impossible, to look at the dynamic figure groupings and rugged brushwork of such early paintings by Beckmann as Drama (1906; destroyed in World War II), Crucifixion (1909; Collection Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt), or Battle of Amazons (1911; The Robert Gore Rifkind Collection, Beverly Hills) without thinking of the example set by Corinth. Subsequently the younger painter developed out of this tradition new symbols for the visions, aspirations, and suffering of modern man.

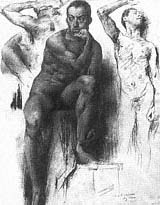

Figure 92

Lovis Corinth, Male Nude ,

1904. Pencil and crayon

heightened with white;

dimensions unknown. Formerly

Collection Johannes Guthmann,

Ebenhausen; present

whereabouts unknown.

Photo courtesy

Hans-Jürgen Imiela.

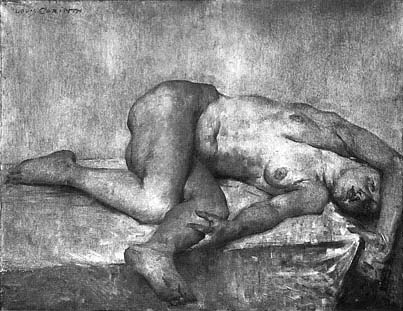

Figure 93

Lovis Corinth, Reclining Female Nude , 1907. Oil on canvas, 96 × 120 cm,

B.-C. 345. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (MG 55/ÖG 3809).

Not surprisingly, Corinth's academically most ambitious figure compositions date from the years during which he was actively involved in teaching. The centerpiece of Corinth's teaching program remained the study of the live model, and the drawing of a male nude (Fig. 92) from December 1904 may well have been done while he worked alongside his students, as he sometimes did. The same concept of form, epitomized in the complicated posture and plasticity of the naked body, is seen in the painting from 1907 of a reclining female nude (Fig. 93). Sprawled awkwardly across a firm support, the

figure was most certainly painted as a demonstration piece, and Corinth published the picture as such in his teaching manual—logically enough, in the chapter on foreshortening.[24] The same illustration further served to support his view, stated several brief chapters later in the book, that "the model is the most important aid the painter has at his disposal. He studies it during his years of training and relies on it when in his paintings he wants to translate the figures of his imagination into reality."[25]

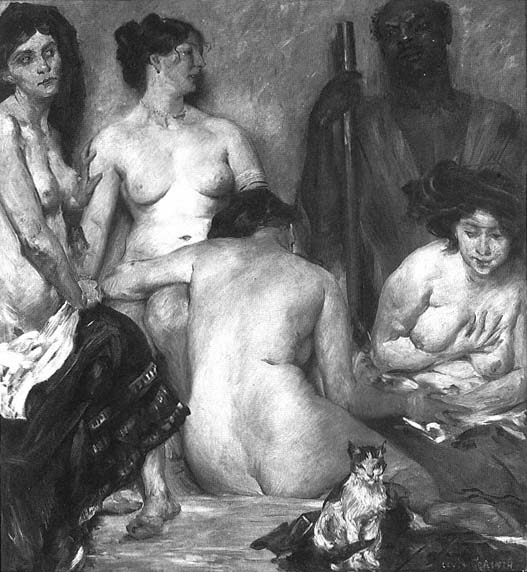

Several of Corinth's figure compositions are actually no more than expanded studies of the nude model, a number of figures having been grouped together in some fashion. These paintings usually bear rather perfunctory titles that more or less describe what is shown. They include The Graces (B.-C. 233), a depiction of three standing female nudes in almost sequential and complementary front, back, and side views, and Girl Friends (B.-C. 297, 298), two pictures in which four nude models in a variety of postures crowd around a chaise lounge. In Harem (Fig. 94) Corinth modified this subject only slightly by adding the figure of a black eunuch. The delightful little cat in the foreground gazes attentively out of the picture and by its prim composure accentuates the languid sensuality of the four women. No wonder pictures like this helped to establish Corinth as one of the great modern painters of the female nude and gained him the reputation of a man himself possessed of a robust libido. It is impossible to say to what extent this reputation was justified. Apparently, however, Corinth believed that the sensual life of artists was intimately bound up with their creative activity, and he is said to have insisted that artists not deprive themselves of sexual gratification, since erotic experiences are wont to increase their creative energy.[26] In his autobiography Corinth expressed a similar opinion when he spoke of his belief that sexual contact enhances an individual's emotional life.[27]

The generally large scale of Corinth's figure compositions more than once tested his skills to the limit. The fate of the ambitious Perseus and Andromeda (B.-C. 208) has already been mentioned (see p. 124). Samuel Cursing Saul (B.-C. 225), a picture with ten life-size figures painted in 1902, was cut apart two years later for similar reasons, leaving only three fragments (B.-C. 226–228). The same misfortune befell the right half of The Ages of Man (B.-C. 273, 275), two pictures from 1904 that were originally joined in a monumental frieze. Corinth is said to have often referred jokingly to this composition as his "matriculation" picture on account of the thirteen life-size figures—twelve of them nude, including a woman, five men, and an assortment of children of all ages—included in it.[28]

Figure 94

Lovis Corinth, Harem , 1904. Oil on canvas, 155 × 140 cm, B.-C. 299.

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt.

Figure 95

Lovis Corinth, Entombment , 1904. Oil on canvas, 172 × 185 cm, B.-C. 272.

Formerly City Hall, Tapiau; destroyed 1915.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

The effort Corinth put into his figure compositions can still be traced in several surviving preliminary studies. This process is especially well documented for the Entombment (Fig. 95), a large work from 1904 that the painter subsequently donated to his hometown of Tapiau, although the painting itself was destroyed when the town was invaded by Russian troops in 1915. The preparatory drawings for the painting include sketches for the composition and individual figure studies done to determine the distribution of the figures and to clarify specific postures and gestures. These drawings were followed by a tempera sketch and an elaborate charcoal drawing on canvas, both approximating the scale of the painting. This was the working method Corinth had learned at the Académie Julian, and, not surprisingly, the original com-

Figure 96

Lovis Corinth, Entombment , 1904. Pencil,

33.6 × 49.2 cm. Staatliche Graphische

Sammlung, Munich (1919:120).

Figure 97

Lovis Corinth, Entombment , 1904. Charcoal heightened with white,

119.5 × 180.0 cm. Sammlung Georg Schäfer, Schweinfurt (271474).

position study for the painting (Fig. 96) has close affinities with one of his Lamentation drawings from 1884. As mentioned previously, Corinth had kept that Paris drawing and eventually published it in his teaching manual to illustrate the "mental gymnastics" an artist must do to visualize the emotions appropriate to various participants in a given action. The gestures and expressions of the figures in the later drawing are intensified, in keeping with Corinth's mature conception.

Although he transferred both the stage-like composition and excessive pathos without major change to a nearly life-size tempera sketch (B.-C. 271), he ultimately chose a simpler solution for both content and form. In the large charcoal drawing on canvas (Fig. 97), which bears the incorrect date 1903, the

nine figures of the original composition have been reduced to four, and the expressions and gestures have been subjected to greater restraint. The figure of Christ, carefully modeled and heightened with white chalk and circumscribed by smooth, reinforced contours, is possibly Corinth's most idealized and heroic nude. Except for the reversal of the pose, the figure recalls the youthful, Adonis-like Jesus in Botticelli's famous Pietà in the Alte Pinakothek. Indeed, Botticelli's shallow space and balanced, frieze-like composition may well have been in Corinth's mind from the beginning. Although he did not sustain the idealized conception of the charcoal drawing in the painting, nonetheless—again like Botticelli—he maintained a precarious balance between overt pathos and introspection.

This borrowing from Botticelli was not an isolated instance. Repeatedly during these years Corinth turned his attention to artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The vertical space and expressive figure types in Golgatha (B.-C. 306) from 1905 have their antecedents in a Crucifixion by Mair von Landshut and in the central panel of the Schöppingen Altarpiece, both then in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin.[29] In 1909 Corinth also made several color drawings after woodcarvings by the Master of Rabenden in the same collection and derived a number of details for the large Carrying of the Cross in Frankfurt (B.-C. 410) from the well-known prints of this subject by the Housebook Master and Martin Schongauer as well as from the corresponding panel of Hans Multscher's Wurzach Altarpiece, now in West Berlin.[30]

Unlike Max Liebermann, who as late as 1905 reproached Matthias Grünewald for having indulged in "painted poetry,"[31] Corinth shared this interest in late medieval German art with several painters of the younger generation. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for example, acknowledged in his chronicle of Die Brücke the immense debt he and his friends owed to Cranach, Beham, and other German old masters.[32] Max Beckmann first learned to admire Grünewald in 1903, when he saw the Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar, and he eventually counted such painters as Gabriel Mälesskircher, Jörg Ratgeb, and Hans Baldung Grien among those who had given his own art a decisive direction.[33]

But unlike his younger contemporaries, Corinth was not induced by the arbitrary color and form of late medieval German art to move away from nature. Aside from borrowing a compositional device now and then and a few isolated motifs, and no doubt appreciating the grotesque exaggerations of gesture and expression in these earlier paintings, he remained resolutely committed to visual truth. A large preliminary figure drawing of Christ for the Deposition (B.-C. 331) from 1906, which vaguely recalls the same scene in a Lower Rhenish altarpiece from the early sixteenth century in the old Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum,[34] illustrates just how closely he observed the live model.

Figure 98

Lovis Corinth, Samson Taken Captive , 1907. Oil on canvas,

200 × 175 cm, B.-C. 343. Landesmuseum Mainz.

Details such as the joints of the painfully extended arms are studied right down to the diagrammatical rendering of the skeletal structure. Corinth's concern for the veracity of the action in this painting is confirmed by Charlotte Berend, who reports his asking her whether one can really tell exactly how the nails that still hold Christ's feet fastened to the cross are being removed.[35]

Corinth relied on early German sources only for his Passion scenes; some of his other figure compositions were derived from the great masters of the baroque. The Rape of Woman (B.-C. 302, 303) from 1904 closely follows Rubens's Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus in the Alte Pinakothek. Samson Taken Captive (Fig. 98) from 1907 is dependent on Rembrandt's gruesome treatment of the

subject in Frankfurt. In each case, however, Corinth intensified the expressive elements of the prototypes with a more pointed naturalism as well as gestural and facial exaggerations. In the picture of Samson's capture, moreover, he assured himself of the greatest possible empathic response by restaging the event so that the figures occupy a space that seemingly extends the viewer's own. The viewer looks downward at the herculean giant whose figure forms a diagonal that leads the eye further back into the scene. Like Rembrandt, Corinth selected the climactic moment of the story when Samson is over-powered by the Philistines. One of them has already fastened a rope to Samson's ankle, two others seek to tie him in chains, and yet another approaches from the upper left, ready to plunge a spear into his eyes. Delilah, kneeling on the bed in the background, leans forward and looks down on the struggle with an expression that combines detached curiosity and cruel satisfaction. The savagery is oddly burlesque because of the crude figure types and the soldier in the lower right, who in the heat of the struggle has been thrown off balance and reacts with humorous consternation to the unexpected loss of his helmet. "Tender souls," as Meier-Graefe observed, might indeed "recoil" from this melee of wildly screaming and kicking figures, but the technical qualities that make "painters rejoice" are evident as well. The subdued earth colors underscore the primeval character of the subject, and the vigorous brushstrokes, reinforced by scrapings with the palette knife, further enliven the violent scene. Corinth ultimately stabilized the centrifugal energy of the composition by arranging the figures, as Rembrandt had done, along two diagonals that converge on Samson's head. He countered these with repeated vertical accents, the most pronounced of which juxtaposes the heads of Samson and Delilah at either end of the painting's central axis, underscoring structurally the consequences of their fateful encounter.

The Bathsheba (B.-C. 349) from 1908 can also be traced to Rembrandt. Once again Corinth modified the prototype by adopting a more provocative frontal view of the subject and by subordinating the Dutchman's poignantly melancholy mood to a coarse and even vulgar naturalism. The motif of milking the goat in The Childhood of Zeus (Fig. 99) is found in both Poussin and Jordaens. Jordaens also anticipated the humorous subplot of the story when instead of painting the nurturing of the infant god, as told by Ovid, he depicted the boy hollering for food because his bowl of milk has been overturned by the goat. Corinth elaborated Jordaens's conception by dwelling on the commotion necessary to keep the boy's cries from being overheard by his father Saturn, who had the nasty habit of devouring his children at birth because it was prophesied that one of them would usurp him. Jupiter's mother Rhea had managed to

Figure 99

Lovis Corinth, The Childhood of Zeus , 1905. Oil on canvas,

120 × 150 cm, B.-C. 305. Kunsthalle Bremen.

save the child by feeding the unsuspecting Saturn a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes and spiriting the newborn off to the slopes of Mount Ida, where nymphs raised him on wild honey and the milk of the goat Amalthea. In Corinth's painting nymphs and satyrs join forces in cheering up the bawling child while his food is being readied, making enough noise in the process to ensure that the boy's cries are not heard. The nymph Adastreia, with the unruly young god in her lap, is distinguished from her bucolic sisters by her decorous gown and restrained demeanor. Seeking to calm the boy, she behaves more like a gentle nursemaid than a wild inhabitant of mountains and

grottoes. For the figure of the young god Corinth drew on his sleeping son, Thomas, whom he had watched one evening sprawled naked in his bed.[36] In the course of the preliminary studies for the painting the motif underwent considerable change, but its final state still testifies to Corinth's practice of developing even his imaginary subjects from life. Similarly, the goat and the rabbits in the picture were painted from the "models" that Corinth habitually assembled for such purposes in his studio.

The episode with the sleeping Thomas that helped to inspire the painting accords with Corinth's advice to his students to paint themes whose "universal human" significance can be understood from one's own life experience.[37] His early tendency to see literary subjects as paradigmatic of human situations (see the discussions of Figs. 35 and 36, pp. 61–64) increased markedly with his move to Berlin and his marriage to Charlotte Berend, informing, as already noted, such pictures as the double portrait of 1902 (see Fig. 83) and the 1906 painting of Charlotte and Thomas (see Fig. 87). The list of figure compositions with both an autobiographic and a universal dimension is indeed long and includes paintings like the Judgment of Paris (B.-C. 301, 338), Rape of Woman (B.-C. 303), and Faun and Nymph (B.-C. 325), a subject with which Corinth also decorated his nuptial bed.[38] Similarly, the archetypal episodes he selected in 1904 to signify the various ages of man (B.-C. 273, 275) apparently took on a personal meaning for Corinth during this year when his son was born. Moreover, although there is no evidence that Corinth was religious in the conventional sense, he felt attuned to the feast days of the Christian calendar. Both the Deposition from 1906 (B.-C. 331) and The Carrying of the Cross from 1909 (B.-C. 410) were painted at Easter time and are specifically so inscribed. And Corinth celebrated his fiftieth birthday in 1908 by painting a melodramatic Lament of the Dead (B.-C. 352), transposing the traditional theme of the Pietà into a generalized memento mori . These paintings, however, are not necessarily a measure of Corinth's inner commitment to these themes. In 1908, for instance, he painted a second "birthday picture," a surrogate self-portrait in the form of a fettered bull in a stable (B.-C. 360).[39]

The eclecticism for which contemporary critics censored Corinth was also his way of teaching by example, as can be seen from the comments he made in his teaching manual on the subject of personal creativity. Unusually well read himself, he considered the study of the history of art fundamental to an artist's education because it introduced young painters to the famous subjects of the Bible and mythology and helped them to understand the great masters of the past.[40] For him an artist's inventiveness manifested itself less in new subjects than in the manner of conceiving an old subject. And he cited as an

Figure 100

Lovis Corinth, Odysseus's Fight with the Beggar , 1903. Oil on canvas, 83 × 108 cm,

B.-C. 253. National Gallery, Prague (0-9238).

example the generations of artists from Giotto to Raphael who drew on the same subjects from the Bible and legends but achieved fame and immortality for their individuality.[41] Corinth's crude naturalism and his sensual and often bawdy interpretations of borrowed motifs were for him thus clearly a mark of originality and a means to self-expression.

Not surprisingly, Corinth often pursued his aggressively naturalistic conception as an end in itself. Such compositions as Samuel Cursing Saul (B.-C. 225), Ages of Man (B.-C. 273, 275), and Lament of the Dead (B.-C. 352) are independent of any prototypes, and in each the pictorial world of the painter's imagination takes on a vividly tangible presence. Another eloquent example is the boisterous composition Odysseus's Fight with the Beggar (Fig. 100) of

Figure 101

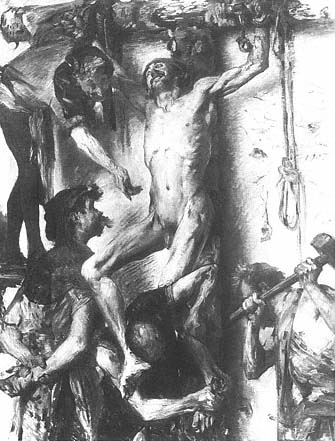

Lovis Corinth, The Large Martyrdom , 1907.

Oil on canvas, 250 × 190 cm, B.-C. 332.

Museum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg.

1903, whose genesis is well documented, right down to the selection of the costumes.[42] What makes this particular work especially interesting is that in it Corinth simultaneously eschewed the academic decorum traditional for such a subject and followed Homer's story almost to the letter. Homer describes the events surrounding the long-delayed return of Odysseus to Ithaca in elaborate detail, including the episode in which the hero, disguised as an old beggar, finds himself insulted by Irus, a common tramp, who threatens to

drive him from the gate of his own home. A fight between the two soon ensues, to the great amusement of the suitors who for years had been wooing Penelope, feasting in Odysseus's palace, and lording it over his people. To their astonishment, Odysseus "made his shirt a belt and roped his rags around his loins, baring his hurdler's thighs," and quickly dispatched his opponent by striking Irus a blow to "his jawbone, so that bright red blood came bubbling forth from his mouth" (Odyssey 18.1–109). As in The Childhood of Zeus , Corinth rendered the commotion in Odysseus's house almost audible in his effort to make the ancient tale come alive.

Similarly remote from convention yet historically justified is the conception underlying The Large Martyrdom , which Corinth painted in 1907 (Fig. 101). To visualize the scene as clearly as possible, he had a cross made for the occasion and periodically hoisted the naked model onto it, keeping the unfortunate fellow strapped there as long as he could possibly bear it. This allowed Corinth to paint the executioners and their victim at the same time.[43] The proximity of the figures to the picture surface and the way they are cut by the frame, especially at the lower margin, almost force the viewer to participate directly in the cruel action. The man at the lower left, seen obliquely from the back, reinforces this response by drawing attention to the figure of Christ. The painting is a far cry from Corinth's earlier Crucifixion (see Fig. 65) and from the exegetic exposition of the subject he was to attempt in the Golgatha Triptych in 1910 (B.-C. 411); both depict Christ's ordeal as a divinely ordained redemptive sacrifice. There is no such promise of redemption in the unmitigated atrocity of this Crucifixion. The clinical emphasis on the executioners' matter-of-fact attitude underscores that these are men punishing a fellow human being.

Role Portraits and Self-portraits in Costume

Corinth's figure compositions of these years are closely related to both his portraits of actors in their roles and his interesting self-portraits and double portraits in which he wore disguises he associated with prototypical human experiences. The role portraits were a direct result of Corinth's work for the theater of Max Reinhardt, with whom he collaborated from 1902 to 1907, contributing designs for costumes, and in some instances sets, for a total of eight productions. Reinhardt had left Otto Brahm's ensemble at the Deutsches Theater in 1902 to become director of the Kleines Theater. The event not only marked a turning point in Reinhardt's career but also ushered in one of the most exciting periods in the history of the Berlin theater. When in 1903 the

Kleines Theater proved too small to hold the audiences that Reinhardt's productions attracted, the enterprising young director rented the Neues Theater as well. In 1905 he assumed responsibility for the Deutsches Theater and the following year extended his reign to the Berliner Kammerspiele.

For years Otto Brahm had fought for the recognition of naturalism on the German stage; Reinhardt now sought to reveal the content of any drama through expressive features in both acting and decor.[44] Assigning a significant role to the stage designer, he eventually achieved a synthesis of content and appearance by using sets and costumes not merely to create the illusion of nature and historical plausibility but to reveal the very essence of the play.

This new emphasis on creating an evocative milieu seems to have found its first full expression in Reinhardt's staging of Maeterlinck's Pelléas und Mélisande , which opened on April 3, 1903, at the Neues Theater. Corinth designed the costumes for the play and together with Leo Impekoven also worked on the sets. Unfortunately, only a fragmentary image of Corinth's work for the theater can be reconstructed from scattered reviews and a few surviving photographs. That Corinth and Impekoven successfully transformed the naturalistic stage into an instrument of greater expressive force is suggested by Carl Niessen's observation on the scenery for Pelléas und Mélisande : "Just as in Maeterlinck's poetic world reality lies behind things and can only be imagined with apprehension and longing, so a mysteriously threatening darkness emanates from the slender gray trees of a forest."[45] And Max Osborne speaks of the same setting as "a fairyland with wide open eyes, a world of mystery and fathomless depth, illumined for a brief moment by a ray of light."[46]

The most controversial play on which Corinth collaborated with Reinhardt was Oscar Wilde's Salome , first performed in Germany before a private audience at the Kleines Theater on November 5, 1902. The play premiered before a general audience almost a year later, on September 29, 1903, at the Neues Theater. Corinth designed the costumes; the sculptor Max Kruse was in charge of the sets. Kruse replaced the customary painted backdrop with a new type of three-dimensional stage architecture that was to become a hallmark of Reinhardt's productions. Beyond Herod's palace, flanked by guardian monsters and lions, was a gloomy night landscape. The shadows cast by the statuary and the building blocks of the scenery created a sense of foreboding as soon as the curtain rose. Corinth's costumes added barbaric splendor to this ominous mood. In their garish magnificence, the multicolored robes, encrusted with colored stones, expressed the high-pitched depravity that propelled the lurid plot.

In addition to his work on Salome and Pelléas und Mélisande , Corinth designed costumes for Hofmannsthal's Elektra (1903) and Gorki's Nachtasyl (1903), the sets for Wedekind's König Nicolo (1903), and perhaps both the sets and costumes for Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor (1903). He also designed figurines for the 1907 productions of Hamlet and Lessing's Minna von Barnhelm .[47]

Corinth's work for the Berlin theater may well have helped to intensify the dramatic character of his contemporary figure compositions, for despite the demands he made on his models, it is unlikely that these paintings were entirely staged in the studio. They resulted from a synthesis of content and appearance, a pictorial challenge to which Corinth alluded in his teaching manual when he explained the special difficulty of depicting an actor in a given role, a task that requires coming to terms not only with the reality of the sitter but also with the illusion of the disguise.[48]

In Gertrud Eysoldt (1870–1955), whom he painted in January 1903 in the title role of Oscar Wilde's Salome (Fig. 102), Corinth encountered an unusually versatile actress whose ability to bring to life the heroine's hybrid character allowed him to experience the biblical figure directly. Eysoldt imbued Herodias's daughter with both childlike innocence and lustful cruelty. According to Tilla Durieux, another great exponent of the role, Eysoldt's body resembled that of a child and she knew how to accentuate the ambivalence of her child-woman persona without attracting the attention of the censors.[49] Unlike the anecdotal figure composition he had devoted to the subject in 1900 (see Plate 12), Corinth's role portrait sought to capture the ambiguity of the character's emotions as invoked by Eysoldt. Soon after the play's first private performance at the Kleines Theater, she posed in Corinth's studio, wearing the costume and the jewelry he had designed for her and holding the dish with the Baptist's severed head, a grisly prop borrowed for the occasion from Reinhardt's theater. Unaided by the ambience of the stage action, Eysoldt has assumed the character of the vile princess in the play's closing scene. Her wish fulfilled, Salome has taken possession of her prize and anticipates the ecstasy of kissing the dead prophet's lips. Without any further reference to Wilde's play, Corinth in this portrait represented a generalized image of depravity, partly, perhaps, in response to the then current vogue for pictures of the prototypical femme fatale but surely also out of his own interest in the universal human dimension.

The special nature of the Eysoldt-Salome portrait is evident if the painting is compared either with Max Slevogt's portrait of the Philippine dancer Marietta de Rigardo (1904; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Neue

Figure 102

Lovis Corinth, Gertrud Eysoldt as Salome , 1903. Oil on

canvas, 108 × 84 cm, B.-C. 252.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

Meister) or with Slevogt's portrait of the singer Francesco d'Andrade in the role of Mozart's Don Giovanni, the so-called White d'Andrade (1902; Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart), which was exhibited with great success at the Berlin Secession in 1902. Slevogt re-created in both paintings the excitement of an actual performance and thus—in contrast to Corinth—invited the viewer to experience these pictures in a specifically theatrical context.

Corinth's portrait of Rudolf Rittner (1869–1943) in the role of Florian Geyer (see Plate 16), painted in 1906, is no doubt indebted to Slevogt's example insofar as it emphasizes physical action rather than psychological expression. The painting shows the actor in the climactic scene from the last act of Gerhart Hauptmann's drama about the Peasants' Rebellion. Having sought refuge at Castle Rimpar, Florian Geyer has been routed out by his enemies. Exhausted and outnumbered, he summons all his strength and counters the demand to surrender with a thundering challenge. A few moments later he is killed by a shot from the crossbow of Schäferhans.

Figure 103

Lovis Corinth, Tilla Durieux as a Spanish Dancer ,

1908. Oil on canvas, 85 × 60 cm, B.-C. 350.

Sophie Althaus, Riezlern.

Rittner, whom Max Reinhardt called a man of "healthy, strong, impulsive temperament,"[50] was the ideal interpreter of Hauptmann's hero and secured for Florian Geyer a permanent place in the German repertoire when Otto Brahm revived the play at the Berlin Lessingtheater in 1904. In Corinth's painting too the actor and the character have become one. Yet in Rittner's vigorous portrayal Corinth himself found embodied not only the essence of Hauptmann's drama but also a struggle transcending that of the historical person. The large size of the painting monumentalizes one person's battle against an unknown fate. Although Corinth depicted an anecdotal moment in the action, he isolated the actor—as in the Salome portrait of Gertrud Eysoldt—from the larger narrative context of the play, replacing the hall at Rimpar with a neutral ground. And Florian Geyer's enemies are anonymous foes whose threat is all the more awesome because they cannot be seen.

The portrait that Corinth painted in 1908 of Tilla Durieux (Ottilie Godeffroy, 1888–1971; Fig. 103) was not inspired by a theatrical performance. The

actress's posture is motivated by nothing more than the desire to create a mood appropriate to the long-fringed scarf she wears over her left shoulder—a gift from Paul Cassirer, who had brought it earlier in the year from Spain. Nonetheless this painting is connected to the role portraits of Eysoldt and Rittner. The only difference is that Durieux does not play a specific part but expresses her joy in a prototypical context. For the moment she simply is "la belle Espagnole dansante la sequedilla," as the inscription—written, though not entirely idiomatically, in French, perhaps in allusion to Bizet's opera—in the upper left corner of the canvas indicates. The ease with which Durieux brought to life virtually any character has become legendary. She played leading roles in the dramas of Shakespeare and Schiller and was equally at home in the naturalist and symbolist plays of Hauptmann, Shaw, Wedekind, and many others. Her range and power of characterization made her the quintessential "Reinhardt actor," for Reinhardt thought of the theater as the collective manifestation of human experience, and he demanded that an actor use a role to fathom his own inner being: "The actor must not disguise but reveal. . . . With the light of the poet he descends to still unpenetrated depths of the human soul, and from there he emerges—hands, eyes, and mouth full of miracles."[51] Tilla Durieux echoed Reinhardt's insistence on self-revelation when she called the actor "an exhibitionist devoted to truth," who tears off every mask before the public until the throbbing flesh lies exposed.[52]

This intuitive approach to acting parallels Corinth's approach to his role portraits, his tendency to enlarge their meaning beyond the historical-ideal truth of the characters depicted, and also sheds light on a group of self-portraits in which he wore various costumes to engage in a self-revelation not possible in the conventional self-portrait. Seven of the eleven self-portraits he painted during his first ten years in Berlin show Corinth in some sort of disguise. In the earliest of these, from 1905, he depicted himself as an ecstatic bacchant with a wreath of vine leaves on his head (see Plate 17). In keeping with Durieux's demand that actors expose themselves in their roles, Corinth here cut through surface appearances by attacking the canvas with ferocious strokes of the palette knife, transferring his heightened emotional state to the texture of the paint itself. According to Charlotte Berend, this disguise came quite naturally to the painter. "When Corinth wound vine leaves in his hair, when he lifted his glass and embraced his bacchic young wife, the world around him changed into the realm of Dionysus, to whom he felt closely allied."[53] In 1908 Corinth elaborated the bacchic allusions of the double portrait of 1902 (see Fig. 83) into a more specific costume piece (B.-C. 355) that does indeed vividly illustrate Charlotte Berend's recollection, except that the bacchante at the painter's side is not his wife but another model who hap-

pened to be conveniently at hand. Corinth's sensuous nature was apparently evident to perceptive eyes in a more public context as well, as the following irreverent description of the painter by Meier-Graefe indicates:

Like a polar bear with small red eyes he moved through the ballrooms of Berlin. He looked greedily at many a banker and at many a banker's wife as she danced in his arms: a pig ripe for slaughter! It was one of the joys of the Berlin winter to watch him dance. At dinner he always had two jugs of wine next to his plate. People spoke to him about Impressionism and sensibility. Corinth was, in turn, Florian Geyer, Samson, Arminius the Liberator, a tamed Hun. If one half-closed one's eyes, one saw naked limbs move underneath shaggy fur. One young lady swooned.[54]

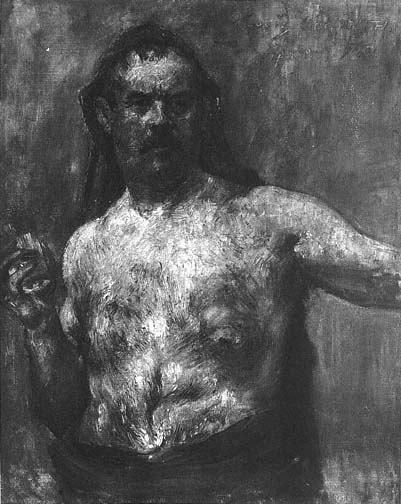

Closely related to the bacchic self-portraits are two self-portraits, from 1907 (Fig. 104) and 1909 (B.-C. 400). In both Corinth is nude except for a curious headdress of red cloth that trails down over his back and shoulders and, in the earlier work, is gathered up around the waist. In each case the painter projects an image of physical vigor on a primeval level, and both self-portraits have been seen as conjuring up memories of "lost cults, . . . drink offerings, and ancient mysteries."[55] In each work, however, Corinth's skeptical expression as he gazes at his mirror image is puzzling. He seems to be contemplating an illusion he knew he could not represent. The mood of uncertainty is further emphasized by the word ipse inscribed on the painting from 1907 and the even more eloquent inscription on the later work: Aetatis suae LI . That Corinth's health was seriously undermined at the time he painted these pictures is suggested by the recollections of his student Margarethe Moll. Writing about the circumstances surrounding the portrait he painted of her in 1907 (B.-C. 340), she mentions that the hands of the painter, then only forty-nine years old, trembled noticeably and that during one of their outings Corinth had considerable difficulty entering and leaving their boat without assistance.[56]