Chapter 1—

The Camera-Eye:

Dialectics of a Metaphor

It's an obsession, really, of the eye. He'd sell his own mother for a look.

—Gilette in Sidney Peterson's Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur

Long ago, I pointed to the lens and said the trouble was here!

—Picasso, conversation with David Douglas Duncan

1—

"Everybody who cares for his art, seeks the essence of his own technique," said Dziga Vertov.[1] This characteristically modernist "mystique of purity," as Renato Poggioli has called it, pervades the avant-garde tradition and produces the desire "to reduce every work to the intimate laws of its own expressive essence or to the given absolutes of its own genre or means."[2] A typical exponent of the essentialist position was Germaine Dulac, who wrote in 1927, "Painting . . . can create emotion solely through the power of color, sculpture through ordinary volume, architecture through the play of proportions and lines, music through the combination of sounds." Thus, Dulac argued, it is imperative for film artists "to divest cinema of all elements not particular to it, to seek its true essence in the consciousness of movement and of visual rhythms."[3]

Probably the best known among the early candidates for cinema's "true essence" was Louis Delluc's photogénie . Jean Epstein declared, "With the notion of photogénie was born the idea of cinema art."[4] But Epstein also admitted, "One runs into a brick wall trying to define it."[5] The best description Delluc could come up with was, "[A]ll shots and shadows move, are decomposed, or are reconstructed according to the necessities of a powerful orchestration. It is the most perfect example of the equilibrium of photographic elements."[6]

The concept of photogénie simply did not get to the heart of the matter. It directed attention to the image—"the equilibrium of photographic elements"—but not to the properties or "elements" of the image itself. Not, in other words, to the "true essence" of cinema. Other avant-garde filmmakers and critics looked deeper and found cinema's basic principles in three interrelated elements: light, movement, and time.

"For cinema, which is moving, changing, interrelated light, nothing but light, genuine and restless light can be its true setting," said Germaine Dulac.[7] Louis Aragon called cinema "the art of movement and light."[8] And even the leading proponent of photogénie , Louis Delluc, wrote, "Light, above everything else, is the question at issue."[9] Coming closer to the present, we find Jonas Mekas declaring, "Our real material had to do with light, color, movement."[10] Stan Brakhage has called light "the primary medium" of film. "What movie is at basis is the movement of light," he has said. "As an art form really, the basis is the movement of light."[11] For Ernie Gehr, "Film is a variable intensity of light, an internal balance of time, a movement within a given space."[12] According to Michael Snow, "Shaping light and shaping time . . . [are] what you do when you make a film."[13] For Peter Kubelka, "Cinema is the quick projection of light impulses."[14]

Although Kubelka, among others, has insisted that movement is merely an illusion produced by the "quick projection of light impulses," some filmmakers regard movement as, in the words of Slavko Vorkapich, "the fundamental principle of the cinema art: [cinema's] language must be, first of all, a language of motions."[15] In a manifesto in 1922, Dziga Vertov called for "the precise study of movement," and added, "Film work is the art of organizing the necessary movements of objects in space." For Vertov, the recording of moving objects was less important than "organizing" their movement and if necessary "inventing movement of objects in space" through frame-to-frame and shot-to-shot relationships.[16] These relationships—or "intervals" in Vertov's terminology—are temporal as well as spatial. They are the basis of what Snow calls "shaping time." As Maya Deren has put it, "The motion picture, though composed of spatial images, is primarily a time form ."[17]

"Light, color, movement," "the movement of light," "the quick projection of light impulses," "light and time," "a time form"—such phrases reflect the specific interests of individual filmmakers but taken together they specify film's "true essence" in terms appropriate to the avant-garde's "mystique of purity": "light-space-time continuity in the synthe-

sis of motion," in Moholy-Nagy's neat formulation.[18] What is most significant for our present purposes is that the same terms can be applied to visual perception . The basic requirements for seeing are also light, movement, and time. As one researcher has put it, "The eye is basically an instrument for analyzing changes in light flux over time."[19] That succinct statement delineates a common ground for vision and film, and it points the direction I will take in seeking a perceptual basis for the visual aesthetics of avant-garde film.

When we look at the world around us, we do not, as a rule, see "changes in light flux over time." We see solid objects moving and standing still in a well-defined three-dimensional space (at least, that is what we see in the most focused, central area of our vision). Nothing would be visible, however, were it not for the "light flux" entering our eyes through the pupil and flowing over the photosensitive cells lining the back of our eyeballs. Experiments have shown that when the retinal cells receive a steady, unchanging light, when the stimulus is absolutely fixed and unvarying, the cells quickly "tire." They stop sending the information our brain needs to construct the visual world we see lying in front of our eyes.[20] Thus there has to be a "flux," a movement of light over the retinal cells; otherwise, we see nothing at all. (If the sources of light do not move, the eye's own movements will keep the light moving across the cells.) "All eyes are primarily detectors of motion," R. L. Gregory points out, and the motion they detect is of light moving on the retina.[21] Only by these changing patterns of illumination can the world outside our eyes communicate with the visual processes of the brain. From that communication emerges our visual world.

Since light moving in time is the common ground of vision and film, perhaps it was inevitable that avant-garde filmmakers seeking the "true essence" of their medium would hit upon the "essence" of vision as well. Avant-garde filmmakers, especially the filmmakers of the 1920s, did not necessarily make a conscious effort to equate the basic elements of cinema with the basic processes of visual perception. Whether they did so or not, their work has been influenced by an implicit equation between cinema and seeing that this chapter is devoted to making explicit.

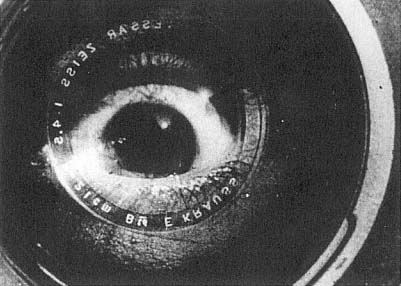

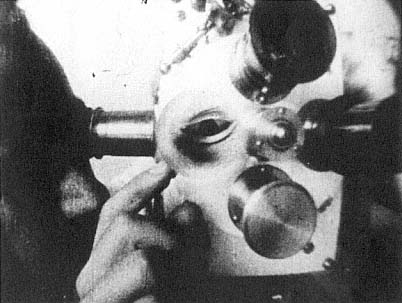

The superimposed eye in the camera lens in Vertov's The Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Man Ray's Emak Bakia (1926) is in fact an explicit depiction of that implicit equation. Less explicit references to the relationship of film and vision occur in many other images of eyes created by avant-garde filmmakers. What Steven Kovaks has called "the leitmotif

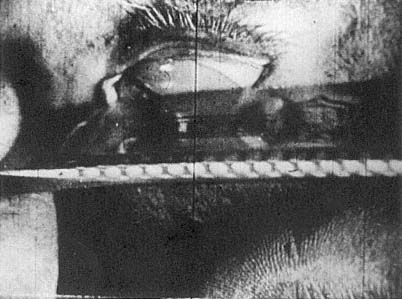

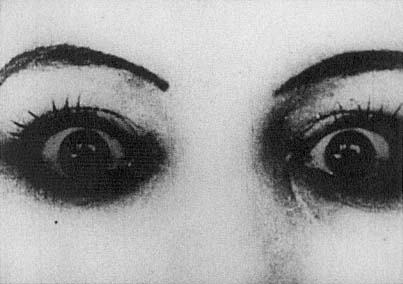

of the eye" in Emak Bakia can be traced throughout the history of avant-garde film.[22] To mention a few examples: the infamous sliced eyeball in Un Chien andalou (1928), the photograph of an eye operation in Paul Sharits's T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968), the close-ups of Kiki's eyes in Léger's Ballet mécanique (1924), the oriental eye at the keyhole in Cocteau's Blood of a Poet (1930), the artist's escaped eyeball in Sidney Peterson's The Cage (1947), the Eye of Horus in Kenneth Anger's Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954, revised 1966 and 1978) and Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969), and the "cosmic eye" created by swirling clouds of color in several of Jordan Belson's films. To end this potentially endless parade of avant-garde eyes are two especially pertinent examples: the extreme close-up of an eye at the beginning and end of Willard Maas's Geography of the Body (1943) and an eye super-imposed over a reclining woman near the end of Brakhage's Song I (c. 1964).

The eye in Geography of the Body alludes directly to the extremely close and (literally) magnified seeing that is the principal concern of that film—not the voyeur's secret sexual gratification but the explorer's fascination with the human body as terrain seen for the first time.[23] Brakhage's Song I also alludes to visual exploring, or what Brakhage would call the "adventure of perception," which should prompt all filmmaking. The eye in that film, which Guy Davenport has called "an overply, the flesh window," is seen in the world it sees, as it sees the world.[24] The Brakhagean eye is a participant-observer (perhaps the anthropologist rather than the explorer is the appropriate analogue). It refers specifically to the inseparability of seeing and filmmaking—as do Vertov's and Man Ray's images of the eye in the camera lens. As I pointed out in the Introduction, there are significant differences between Brakhage's emphasis on "the flesh window" of the human eye, and Vertov's and Man Ray's emphasis on the "mechanical eye" of the camera. But both make direct reference to the metaphor of the camera-eye and more indirectly to film as (in James Broughton's phrase) "a way of seeing what can be looked at."[25]

To show that film is "a way of seeing," that it resembles visual perception in basic and specific ways, I will reexamine the metaphor of the camera-eye. Visualized directly through the superimposition of eye and camera lens, alluded to indirectly in many other variations on "the leitmotif of the eye," it is a metaphor so intrinsic to the visual aesthetics of avant-garde film that despite (or perhaps because of) its familiarity, it requires close, careful explication.

The eye and lens superimposed in

The Man with a Movie Camera

(Dziga Vertov).

The eye replaces the lens in Emak Bakia

(Man Ray).

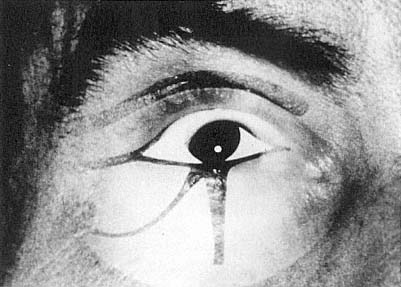

A razor slices the eye in Un Chien andalou

(Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali).

An eye operation in T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G

(Paul Sharits).

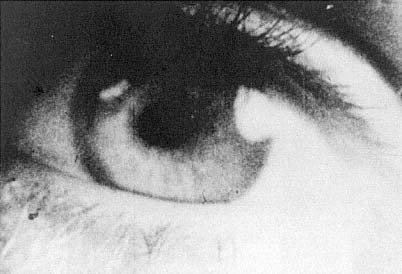

The eyes of Kiki, the Parisian model, in Ballet mécanique

(Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy).

The eye at the keyhole in Blood of a Poet

(Jean Cocteau).

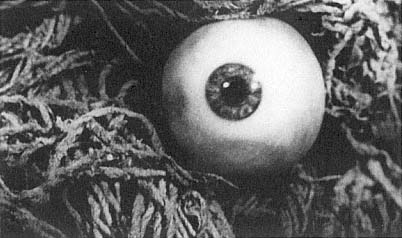

The escaped eyeball of an artist caught in a mop in The Cage

(Sidney Peterson).

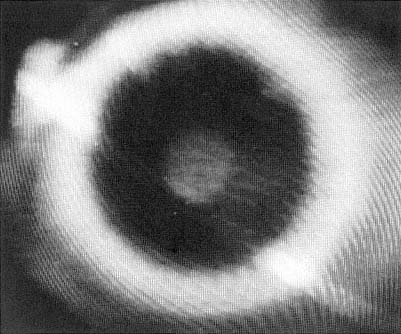

The Egyptian Eye of Horus superimposed on

a human eye in Invocation of My Demon Brother

(Kenneth Anger).

The "cosmic eye" in Infinity

(Jordan Belson, video version).

The magnified eye in Geography of the Body

(Willard Maas).

The superimposed eye in Song I

(Stan Brakhage).

2—

The metaphor of the camera-eye is constructed of synecdoches. That is to say, the eye and the camera are parts standing for the whole of their respective visual apparatuses. Vision is no more a product of the eye alone than pictures (especially the "moving pictures" of cinema) are made by the camera alone. In each case, what we see is the result of complex processes that only begin in the eye and the camera. No doubt it is because they house the beginnings of their respective ways of seeing that the eye and the camera have acquired their synecdochic weight. They are the outermost extensions of visual systems whose other structures and functions are hidden inside the skull and inside film labs, editing rooms, and projection booths. Even the crucial light-receptors of each system (the retina and the film) are hidden from view. An analysis of the camera-eye metaphor may properly begin with the eye and the camera per se, but if it is to demonstrate the metaphor's relevance to the visual aesthetics of avant-garde film, it must go on to seek other, less apparent correspondences between the two visual systems.

The classic essay on the subject is George Wald's "Eye and Camera," published in Scientific American in 1950. Wald first asserts, "Today every schoolboy knows that the eye is like a camera," and summarizes these likenesses as follows:

In both instruments a lens projects an inverted image of the surroundings upon a light-sensitive surface: the film in the camera and the retina in the eye. In both the opening of the lens is regulated by an iris. In both the inside of the chamber is lined with a coating of black material which absorbs stray light that would otherwise be reflected back and forth and obscure the image.[26]

Wald goes on to point out similarities in the light-sensitivity of the film and the retina. Just as a fine-grained, "slow" film is designed for high intensities of light and a more coarsely grained, "fast" film for low intensities of light, so the retina has two kinds of receptor cells: the cones, which operate in bright light and provide the more sharply defined details of our visual world, and the rods, which work at lower light levels and are the source of the coarser, less sharply defined details in the peripheries of our visual world.

Moreover, the cones and rods are on the ends of minute stalks that respond to the light's intensity, so that when the light is dim, the rods are pulled forward and the cones pushed back; when the light is bright the cones move forward and the rods draw back. As Wald says, "One could scarcely imagine a closer approach to the change from fast to slow film in a

Comparable structures and functions of the camera and the eye

(adapted from George Wald, "Eye and Camera,"

Scientific American , July 1950).

camera." In subsequent layers of the retina, according to more recent research by Frank S. Werblin, the bipolar cells emphasize high contrast in the retinal image, while the amacrine and ganglion cells moderate contrasts. "It is as if," Werblin writes, "a camera system could switch automatically from a high-contrast film to a low-contrast film when it encountered a rapidly changing or a very contrasty scene."[27]

For Wald, the retina and photographic film offer another kind of analogy, because of their chemical response to light. The rods contain a pigment, rhodopsin, that bleaches in the light and is resynthesized in the dark. This led the nineteenth-century physiologist Willy Kühne to devise an experiment in which he was able to take a picture with the living eye of a

rabbit. First, the rabbit's head was covered to allow rhodopsin to accumulate in the rods. Then it was uncovered and held so that it faced a barred window. After a three-minute "exposure," the animal was killed, its eye removed, and the rear half containing the retina "fixed" in an alum solution, so that the bleached rhodopsin could not be resynthesized. "The next day," Wald reports, "Kühne saw, printed upon the retina in bleached and unaltered rhodopsin, a picture of the window with a clear pattern of its bars."

Wald's own variation on this experiment was to extract rhodopsin from cattle retinas, mix it with gelatin on celluloid, expose it to a pattern of black and white stripes, then "develop" it in darkness with hydroxylamine. The result was a "rhodopsin photograph" showing the same black and white pattern. Thus, just as exposure to the light produces a "latent image" in a film's emulsion, so, Wald argues, "light produces an almost invisible result [on the retina], a latent image, and this indeed is probably the process upon which retinal excitation depends. The visible loss of rhodopsin's color, its bleaching, is the result of subsequent dark reactions, of 'development.' "It is now known that the cones also contain rhodopsin-like pigments that make color vision possible, which leads John Frisby to write, "So really the rods and cones are two distinct light-sensitive systems packaged together into a single 'camera'—the eye."[28]

If the vertical bands of light and dark gray make one think of the barred window that left its lasting impression on the retina of Kühne's rabbit, it is an appropriate—if somewhat ironic—association, so long as one remembers that neither image duplicates actual vision . They are simply chemical traces of rhodopsin's response to the "light flux" that reaches the retina from the outside world; they are images of "the process upon which retinal excitation depends," as Wald put it. Nevertheless, Wald's and Kühne's experiments show the eye to be more like a camera, and seeing more like photography, than is often recognized. They strengthen the metaphor of the camera-eye by grounding it in processes that can be scientifically verified. In Wald's words, "The more we have come to know about the mechanism of vision, the more pointed and fruitful has become its comparison with photography."

As convincing as that may sound, it is not a view all scientists of vision share. In Handbook of Perception R. M. Boynton offers a pointed and thorough rebuttal:

The eye most emphatically does not work just like a camera, and the differences are worth discussing. The eye is a living organ, while the camera is not. In a camera, light passes through the image-forming optics of high refractive index, and then back again into air before striking the film plane. In the eye,

high-index media are encountered as light enters the eye at the outer surface of the cornea, but the light never again returns to air. The control of pupil size begins with the action of light upon the identical photoreceptors that initiate the act of vision, while the camera's photoelectric analog, when there is one, is located so that the light falling upon the photocell is not affected by the size of the opening in the iris diaphragm. The lens surfaces in most cameras are sections of spheres, to which an optical analysis developed for spherical components can properly be applied. There is no spherical surface anywhere in the eye. The camera lens is homogeneous in its refractive index (or at most contains a few such distinct elements, each of which has this property). The lens of the eye is layered like an onion, with the refractive index of each layer differing slightly from the next. Cameras have shutters and utilize discrete exposures, either singly or in succession. The pupil of the eye is continuously open. Cameras must be aimed by someone; the eye is part of a grand scheme which does its own aiming. Images produced by photographic cameras must first be processed and then viewed or otherwise analyzed; the image produced upon the retina is never again restored to optical form, and the mechanisms responsible for its processing are perhaps a billionfold more complex than those used in photography.[29]

The list of differences "could be expanded," as Boynton says, but it is surely long enough to discourage anyone from turning to literal-minded scientists for validation of the camera-eye metaphor.

The fact that the eye does not work "just like a camera" is indisputable, but it is also irrelevant, since the significant similarities between the two are metaphorical, not literal. Boynton's effort to discredit the camera-eye metaphor is useful, however, for several reasons. First, it specifies the basic difference underlying the likenesses implied by the metaphor. The difference is between a machine and, in Boynton's words, "a living organ"—between Vertov's "mechanical eye" and Brakhage's "flesh window." It is the basis of the dialectical relationship of eye and camera, from which the visual aesthetics of avant-garde film have emerged.

Second, Boynton repeats a common objection to equating the camera and the eye when he emphasizes the difference between the photographic image and the retinal image. It is true that the retinal image is "never again restored to optical form" and is nothing more than a stimulus for retinal cells at one of the earliest stages in the total visual process. What must be stressed, however, is that the production of an optical image in the camera and in the eye, though essential to both visual processes, is not in itself the basis of their most significant resemblances. Light moving in time—not images—is the "essence" they share.

A third point arises from Boynton's critique of the camera-eye metaphor. Like virtually all commentators on the camera and the eye, Boynton

implies that the photographic image is the visible equivalent of the image cast by the lens on the film plane of the camera. In still photography this is more or less true (allowing for the inevitable differences created by the chemistry of processing and printing photographs), but in cinema, it is not. What the film viewer sees are not images on film but images projected on a screen . These images are created by light moving in time, and therefore they much more closely approximate the sources of seeing than do the images fixed in the emulsion of photographic film.

Cinematic images partake of the same "optical flow" described by Gunnar Johansson: "The optical flow of images into the viewfinder of a camera (or into the camera itself when the lens is open) corresponds to the optical flow impinging on the retina during locomotion."[30] In fact, since the eyes are always in motion, the image falling on the retina is always flowing over the retinal cells. Of course, cinematic images can not reproduce the same "optical flow" that entered the camera. There are too many intervening steps to permit the original "optical flow" to emerge from the projector unchanged (not to mention the fact that cinematic images may be made without the use of a camera at all). They can, however, represent the same kind of "flow" that impinges on the retina, the only difference being that their "flow" is shaped by the filmmaker through the materials and processes of the cinematic apparatus. Thus the camera-eye metaphor continues to be valid, if one takes into account the actual nature of the film image and conditions of film viewing.

A fourth point is suggested by Boynton's sentence "Cameras must be aimed by someone; the eye is part of a grand scheme which does its own aiming." The camera-eye metaphor should remind us that the camera, too, is "part of a grand scheme" that controls the way it is "aimed" at the world. Whether the camera is held in the hands of Stan Brakhage and "aimed" by Brakhage's intuitive response to his feelings and immediate environment, or attached to a motorcycle's handlebars and "aimed" by Vertov's cameraman as he steers around an inclined track, or perched atop Michael Snow's elegant remote-controlled machine and "aimed" at the Québec landscape by electronic impulses scripted by Snow—the camera is integrated in "a grand scheme which does its own aiming." Metaphorically, it is like the eye in its own "grand scheme" of muscles, tissues, nerves, and brain cells. Here, in fact, is another way of comparing the eye and the camera as synecdoches representing a whole—the "grand scheme"—of which each is a particularly conspicuous but totally integrated part.

Despite the objections raised by Boynton, then, the camera-eye meta-

phor not only continues to make sense but gains strength and pertinence as it is given closer scrutiny—so long as (1) it is understood to be a metaphorical juxtaposition, not a literal equivalence, producing a dialectical relationship of mechanical and organic structures and functions; (2) its implied similarities between the retinal image and the photographic image are recognized to be less relevant than its allusion to the flow of light essential to both visual and cinematic perception; (3) it is treated as a comparison of interrelated parts and processes constituting the "grand schemes" of visual and cinematic perception.

3—

The camera's "grand scheme" includes taking in the light (shooting), converting the light to images on film (developing), arranging the images in a meaningful order (editing), reproducing that order in combination with all other visual effects (printing), and reconverting the images into a "light flux" (projecting), from which the viewer's own visual system constructs the cinematic image. The original "light flux" entering the camera goes through a series of interactions and transformations, so that the light emerging from the projector will take on the shapes and rhythms imposed by the total filmmaking apparatus (in which the filmmaker plays an important though not necessarily the chief role). Only in this extended sense can one properly call the cinematic image a representation of what the camera "sees."

Only in an equally extended sense can one refer to what the eye "sees." The visual world is a product of the brain. The brain's building materials are electrical impulses traveling through millions of cells in a network connecting many different parts of the brain. No single line of cause-effect events (like those that constitute the camera's "grand scheme") can be traced from the eye to the completed visual world. Many parts of the brain contribute to the eye's "grand scheme," and at least some of those parts communicate with each other in an order that scientists have been able to map.

A small area at the back of the brain called the visual association cortex seems to pull together all the information supplied by other parts of the brain. Data on color, motion, and three-dimensionality probably come from the immediately adjacent prestriate cortex which has already received information on shape, size, and spacial orientation from the striate cortex. The so-called hypercolumns of cells in the striate cortex receive and coordinate data arriving (after several intermediate steps) from the

optic nerves, whose ganglion cells make up the last of four layers of cells in the retina. These cells have already begun to make preliminary discriminations between lighter and darker areas and their movements. Their information comes from impulses produced by the rods and cones as they respond to the retinal image. The rods and cones, as we have already seen, have their own specialized functions, the most obvious being the rods' response to the movement of light and the cones' response to the wavelengths (i.e., color) of the light. Although some visual information also comes from nerve cells monitoring the movements of the eyes, it is reasonably accurate to say that the visual process begins when the rods and cones respond to the light moving over them.

(At this point, it should be remarked parenthetically that all visual activity is not initiated by light falling on the rods and cones. Much can be seen when the eyes are closed. There are phosphenes and other visual phenomena produced by the internal workings of the visual system, as well as dreams and visions that are seen as vividly as anything the eyes encounter in the external world. Similarly, not all cinematic images begin in the camera. Film may be exposed directly to the light, and it may be scratched, painted, or otherwise invested with shapes and colors that the projector's light will cast on the screen. Within both "grand schemes," in other words, there are alternative sources of seeing, about which much will be said in the chapters that follow. For the moment, one need only note that the "grand schemes" underlying the camera-eye metaphor do not necessarily require the presence of either a camera or an eye.)

Because light rays entering our eyes cross at the pupil, they produce a retinal image that is upside down and backwards, relative to the visual world as we perceive it. And because the eye moves—not only in large, intermittent movements, but also in minute and continuous jumps and tremors—the image darts this way and that across the retina. The retinal image is fluid and unstable; yet we normally perceive a solid and stable visual world. The retinal image spreads across a curved, two-dimensional surface; whereas, the visual world fills three-dimensional space. These transformations of retinal image into visual world are products of the eye's neural network in the brain.

Actually, the network begins in the eye itself. The cells of the retina develop from the same embryological tissue that produces the brain, and they function just like other brain cells. By surfacing in the eye, the brain makes direct contact with the "light flux." As the retinal cells make their preliminary discriminations, the brain is beginning to "think" about the visual world it will produce. The visual world is the completed "thought."

Although it seems simply to be there, in front of our eyes, the visual world is, in fact, the product of what R. L. Gregory calls the "internal logic" of the brain's visual system, a system based on collecting, comparing, and drawing conclusions from data that is both "stored" in the brain and constantly arriving for the first time via the retinal image.[31] This process, which is still poorly understood, is not nearly as linear and hierarchical as my brief summary may seem to imply, and it is composed of nothing but electrical impulses traveling along millions of neural pathways at the same time. Shape, size, depth, movement, color, texture—all the components of the visual world are really millisecond-by-millisecond configurations of electrical activity in the brain.

4—

Scientists of vision are careful to distinguish between what we see and the sources of our seeing. In one sense the source is the external world from which light flows to the eyes. In another sense, the source is the light itself, or the retinal image formed by the light. In still another sense, the source is the combination of electrochemical computations made by the millions of cells throughout the visual system of the brain. These sources produce what we see, but we do not see them. We see "an internal representation," as David Marr puts it, of what the eye's "grand scheme" has been able to derive from its encounter with "the light flux over time."[32]

Likewise, what we see in cinema is the result of a complex process that begins with the external—or profilmic—world from which light streams into the camera's lens. Like the eye, the camera uses optical principles to form an image and photochemical principles to make that image available to subsequent cinematic processes. After that point, however, the camera's "grand scheme" operates quite differently from the eye's "grand scheme." In the latter, the photochemical transformation of the image on the retina produces changes in the voltage of the retinal cells. Those changes cause electrochemical impulses to pass from cell to cell throughout the brain's visual system until the final constellation of impulses creates what we see as the visual world.

In the camera, the incoming light changes the chemistry of the film's emulsion, producing a latent image that is made visible by chemical processing before it continues on to subsequent stages of analysis, modification, rearrangement, and reimaging within an optical-chemical system, not (as in the brain) a chemical-electrical one. Whereas the brain cells

complete the eye's "grand scheme" without further reference to an image, the collective "brain" of the camera's "grand scheme" continues to work with images until the projector turns them back into the "light flux" received by the viewer's eyes.

The camera-eye metaphor should not be allowed to blur these distinctions, but neither should it be dismissed because of them. Clearly, its relevance varies according to which aspects of the two "grand schemes" are being compared. While the metaphor suits the light-gathering and image-forming capacities of the eye and the camera, it seems to have little relevance to their subsequent production of the visual world and the cinematic image. It can be applied, however, to their over-all function, which is to invest the originating "light flux" with a final, visual form. Neither "grand scheme" is simply a series of relay stations through which the external world sends along visible replicas of itself. Both schemes subject the light to mediating and transforming processes built into their respective visual systems. Looking at visible objects is not the basis of the camera-eye metaphor; rather, it is creating visual representations out of light moving in time.

The dialectic of eye and camera finds its synthesis, then, in the viewer's perception of these visual representations emerging from the "grand scheme" of cinematic production. While this is true of all film viewing, only avant-garde films call attention to that dialectical process and treat its synthesis as an aesthetic problem. As subsequent chapters will show, different avant-garde filmmakers have resolved that problem differently, but all in their own ways have responded to the dilemma raised in the two quotations that serve as epigraphs to this chapter.

In Sidney Peterson's Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur (1949), the model Gilette says of her lover, Nicolas Poussin, "It's an obsession, really, of the eye. He'd sell his own mother for a look." In an afterword to Prismatics: Exploring a New World , David Douglas Duncan recalls that while he was photographing Picasso in his studio, the artist said to him, "Long ago, I pointed to the lens and said the trouble was here!"[33] In these brief quotations we have the visual artist's obsession with seeing (probably the most extreme form of what Arnold Gesell has called "the visual hunger of cultural man") juxtaposed with the artist's deep suspicion of the camera and by implication the photographic process as a whole, because of its dispassionate and manufactured ways of seeing.[34]

Although both sentiments are attributed to painters, their relevance to avant-garde filmmakers should be apparent by now. The "leitmotif of the eye" testifies to the avant-garde's obsession with seeing. The camera-eye

metaphor implies that film artists can satisfy that obsession through the apparatus of cinema. But to do so they must confront and resolve the "trouble" in the lens. Otherwise, the camera will shape their vision to suit its own limited ends. To appreciate the strategies avant-garde filmmakers have employed on behalf of their "obsession of the eye," we must take a closer look at the "trouble" Picasso pointed to. Where did it come from? How did it get built into the camera? What does it imply for a visual aesthetics of film? The next chapter will try to answer those questions.