1—

Painting at a Dead End

The rest of them were artists. Duchamp collects dust.

—John Cage

Among Marcel Duchamp's gestures and artistic interventions, few have created as much controversy or been as puzzling as his putative abandonment of painting.[1] Duchamp begins painting at fifteen, producing a series of competent, if not particularly distinguished, landscapes and portraits, which he qualifies as "pseudo-Impressionist" or "misdirected Impressionism" (DMD, 22). Although Duchamp starts to exhibit his work publicly in 1909, the earliest works of his that are considered significant date to 1910. At the age of twenty-three, his enriched pictorial and compositional vocabulary is deployed in a figurative context, where nudes and group scenes dominate. Reflecting the influence of Paul Cézanne and the Fauvists, the emphatic use of color and design in these works represents a decisive turn toward abstraction. Robert Lebel compares their "acid stridence to that of Van Dongen, and also, German Expressionism" (DMD , 23). By 1911, Duchamp's use of abstraction demonstrates shared affinities with Cubism, insofar as it brings into question the figurative identity of the body through its spatial fragmentation and its serial deployment. At this time he also begins to expand the meaning of the pictorial image by trying to find new ways of illuminating it, either through experiments with gaslight or by exploring how the title may have an impact on the nominal expectations of painting.

At the end of 1911 and culminating in 1912, Duchamp irrevocably establishes his authority as a painter through his signatory work, Nude

Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which is first rejected by the Salon des Indépendants in March, only to be exhibited in Barcelona in May. In late 1912, this work is chosen by Walter Pach to be included in the upcoming International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York (the Armory Show of 1913). It is during this same period that Duchamp begins to incorporate machine imagery and morphology in his paintings, leading to his mechanomorphic paintings. This three-year trajectory that establishes Duchamp's creative identity and credibility as a painter renders his abandonment in 1913 of conventional painting and drawing all the more surprising, if not altogether shocking. At issue is neither Duchamp's failure nor, ironically, his success as a painter but rather his challenge of the limits of pictorial practice.[2] The fact that in 1916 a New York art dealer named Knoedler, after seeing Nude Descending a Staircase, offered Duchamp $10,000 a year for his "entire production" (DMD , 106), alerts us to Duchamp's painterly reputation and financial worth in the nascent New York art world.[3] Duchamp's refusal of this offer at a time when his financial means were limited all the more decisively underscores his choice to move beyond painting in order to challenge the social and institutional conventions that define both pictorial production and the painter.

Thus within this three-year span (1910–13), Duchamp establishes himself as an internationally renowned painter, one who moves decisively from figuration to abstraction, only to begin to question painting altogether. In 1913 Duchamp practically gives up conventional forms of painting, but this does not mean that he stops working. Instead, he begins to experiment with chance as a way of getting away from the traditional methods of expression generally associated with art. He lets pieces of string fall and records the shapes they generate; when his work on glass cracks he accepts the cracks as part of the work.[4] These chance-generated works challenge the position of the artist as autonomous producer and the determinism that defines art as a creative medium. During this period, Duchamp experiments with mechanical drawings, painted renderings, and notations that serve as studies for his seminal work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even.

By 1923, the idea that Duchamp did not just give up painting but art altogether comes into currency. As Joseph Masheck explains: "Duchamp never discouraged it and seems to have enjoyed the mysterious notoriety

that it gave him as well as the silent isolation to carry on his activities out of the limelight. Duchamp was said to have taken up a decided antiart position, abandoning art in favor of playing chess."[5] Thus, from Duchamp's supposed abandonment of painting we arrive (through The Large Glass, which, as I argue, is also a looking glass) at the far more radical conclusion that Duchamp has reneged on art altogether, that he has abandoned art in favor of chess. How do we explain these radical transitions, from figuration to abstraction leading to the abandonment of painting, and ultimately art, given the speed at which these gestures succeed one another? Can these transitions be illuminated by particular events in Duchamp's life, and more specifically, how are they manifest when considering works from this period?[6] Are there conditions or strategies evidenced in these works that dictate a radical revaluation of painting both as artistic practice and as profession?

A small number of biographical details may prove to be significant to our discussion of Duchamp's pictorial origins. Born in a solid French bourgeois family on 28 July 1887 and following in the footsteps of his two brothers Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon and his sister Suzanne, Duchamp also became interested in art.[7] It should be noted, however, that the initial disapproval expressed by his father regarding an artist's career for his sons led his elder brothers to change their names by assuming a pseudonym (Villon, after the renowned medieval French poet François Villon [1431-after 1463]) or partial pseudonym (Duchamp-Villon).[8] Despite the paternal reluctance to endorse the professional choices of his sons and despite the age differences among the siblings, the entire family was deeply steeped in their shared interests in music, art, and literature.[9] It is important to recall, however, that Duchamp's formal art training was limited to one year of studies at the Académie Julien, from 1904 to 1905. Far more significant in his professional formation was his apprenticeship as a printer in Rouen in 1905, in lieu of doing military service. As an "art worker" he received exemption from military service after one year, having passed a juried exam based on the reprints of his grandfather's engravings. From 1905 to 1910, following the example of his brother Jacques Villon, he executed cartoons for two newspapers, the Courier Français and Le Rire. Thus, in addition to his early exposure and family background in art, both engraving and cartooning

were formative media to his development as painter.

The influence of Duchamp's exposure to engraving and cartooning impacted on his efforts to discover alternative ways of conceiving painting and art. Unlike his siblings, Duchamp is not content to simply become a painter, for he will rapidly abandon painting in favor of activities that challenge the very meaning and definition of art. When one considers attentively Duchamp's early works, one is invariably struck by his efforts to put into question the notion of pictorial image, by examining its relation to other frames of reference, the title, or the nominal expectations of the public. Moreover, his early explorations of serial works, or multiples, attest to his efforts to challenge the uniqueness and autonomy of the pictorial image. Engraving and cartooning thus enabled Duchamp to conceive the plastic image in new terms, whose technical and intellectual content opened up the possibility of redefining the notion of artistic creativity as a form of production based on reproduction. Duchamp did not becomean engraver nor a cartoonist. He did, however, draw on the intellectual and speculative potential of these two media, in order to redefine not only painting as a medium but also art itself. The fact that Duchamp began his artistic career as an "art worker" is significant, insofar as it enabled Duchamp to question the creative function of the artist and the meaning of art as a form of making:

I don't believe in the creative function of the artist. He's a man like any other. It's his job to do certain things, but the businessman does certain things also, you understand? On the other hand the word "art" interests me very much. If it comes from the Sanskrit, as I've heard, it signifies "making." Now everyone makes something, and those who make things on a canvas, with a frame, they're called artists. Formerly, they were called craftsmen, a term I prefer. We're all craftsmen, in civilian or military life. (DMD, 16).

In the pages that follow, Duchamp's effort to question the meaning of art as pictorial practice, as an institution, and as a profession will be at issue. The notion of art as "making" enlarges the meaning of artistic activity to forms of production that include not only artisanal efforts but also conceptual insights.

Painting Stripped Bare

I have been a little like Gertrude Stein

—Marcel Duchamp

In his interview with Marcel Duchamp, Pierre Cabanne asks him to explain the key event of his life: his abandonment of painting. Duchamp's response identifies Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 as the turning point. While serving to establish his reputation, the initial rejection of the work alerts him to the norms and strictures that define not just conventional art but also contemporary art movements, such as Cubism:

There was an incident, in 1912, which "gave me a turn," so to speak; when I brought the "Nude Descending a Staircase" to the Indépendants, and they asked me to withdraw it before the opening. In the most advanced group of the period, certain people had extraordinary qualms, a sort of fear! People like Gleizes, who were, nevertheless, extremely intelligent, found this "Nude" wasn't in the line that they had predicted. Cubism had lasted two or three years, and they already had an absolutely clear, dogmatic line on it, foreseeing everything that might happen. (DMD , 17)

Duchamp is less concerned with the rejection of the painting than the fact it embodies a doctrinal gesture—one where a work of art is defined by living up to its nominal expectations. By failing to fall into line, that is to conform to a set of pregiven rules, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was perceived as a challenge to Cubism, whose precepts had already been laid out by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. For Duchamp, the turning point that the Nude represents is not merely its challenge to the public but also to his peers, whose artistic and intellectual expectations define the work's conditions of possibility. For Duchamp this incident was symptomatic of the dogmatic, programmatic character of art, and led him to abandon both painting and the artistic milieus he frequented, in favor of a job as a librarian at Sainte-Geneviève Library in Paris.

Was Duchamp's dramatic gesture an expression of his "distrust of systematization," of his inability to contain himself to "accept established formulas" (DMD , 26)? Duchamp rejects Cubism not just as an artistic movement but as a discipline with a set aesthetic program: "Now, we have a lot of little Cubists, monkeys following the motion of a leader

without comprehension of their significance. Their favorite word is discipline. It means everything to them and nothing."[10] Duchamp deliberately distances himself from the aesthetic agendas of Cubism, since his aim is to "detheorize Cubism in order to give it a freer interpretation" (DMD , 28).[11] If this is true, then one must examine in what sense Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 challenges preestablished Cubist pictorial and generic formulas. Coming in the wake of a series of representational nudes in 1910, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 marks Duchamp's decisive turn from figuration to abstraction. As this study will demonstrate, however, Duchamp's passage through abstraction involves the speculative goal of getting away from "the physical aspect of painting" by putting "painting once again to the service of the mind."[12] As Arturo Schwarz observes, Duchamp's aim was to liberate the notion of painting from its aesthetic function to please the eye, in order to reassess its intellectual potential.[13] Duchamp's efforts to expand the horizons of painting, by exploring the literal and nominal expectations that define it, led to his subsequent abandonment of the medium.

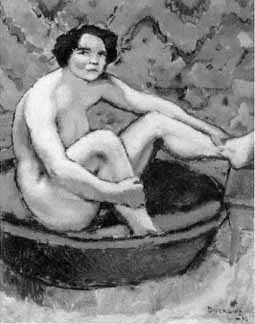

Duchamp's adoption of the nude as pictorial genre did not have entirely auspicious beginnings. It is also interesting to recall that he failed the Ecole des Beaux-Arts competition over a test that involved doing a nude in charcoal (DMD , 21). In 1910, when Duchamp turns to the genre of the nude

Fig. 1.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Seated in a Bathtub (Nu

Assis Dans Une Bagnoire), 1910. Oil on canvas,

36 1/4 x 28 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

after extensive work in landscape and portraiture, his explorations of this subject matter reveal an acute awareness of pictorial traditions and contemporary artistic movements and styles. Schwarz notes that in Nude with Black Stockings (Nu aux bas noirs; 1910), the "use of heavy black lines—characteristic of the Fauves' reaction to the Impressionists' careful avoidance of black—is freely adopted."[14] Duchamp's deliberate deployment of one of the signatory gestures of Fauvism, which is itself a reaction to the aesthetic ideology of Impressionism, suggests his recognition of the plastic and strategic character of artistic conventions. It reflects an understanding of the extent to which an artistic movement may be defined by its strategic response to the aesthetic tenets of a previous, or even contemporary, movement. Duchamp's use of heavy black lines to outline the body, as in Nude Seated in a Bathtub (Nu assis dans une bagnoire; 1910) (fig. 1), Nude withBlack Stockings (fig. 2), and Red Nude (Nu rouge; 1910) (fig. 3), establishes a tension between the rhetoric of drawing and that of color. The black lines emphatically reframe the successive color shadings, thus

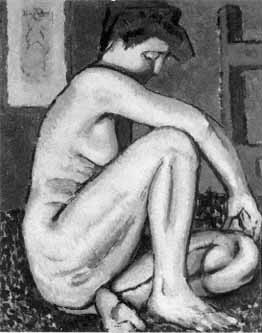

Fig. 2.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude with Black Stockings (Nu

Aux Bas Noirs), 1910. Oil on canvas, 45 3/4 x 35 1/8 in.

Galleria Schwarz, Milan. Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

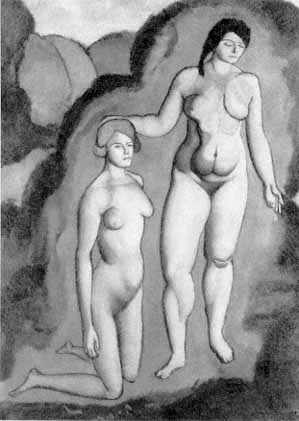

Fig. 3.

Marcel Duchamp, Red Nude (Nu Rouge), 1910. Oil

on canvas, 36 1/4 x 28 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

inscribing a graphic dimension into the painterly impact of these works. In the Red Nude, color as one of the constitutive elements of painting is deployed in a manner that reveals its affinity to engraving. The red shadings and black lines compete as color templates that redefine the pictorial appearance of the nude as a successive set of impressions or imprints.

If these nudes are graphic, it is in their treatment of painting and not in their ostensible subject matter. When comparing Duchamp's Nude with Black Stockings with Gustave Courbet's Woman with White Stockings (Femme aux bas blancs; 1861), one is struck by its unerotic demeanor that resists voyeuristic appropriation as an image. Rather than emphasizing and framing genitality, as the white stockings do in Courbet's painting, the black stockings dismember the body by erasing it from the

Fig. 4.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bush (Le Buisson), 1910. Oil on

canvas, 50 x 36 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and

Walter Arensberg Collection.

knees down. Duchamp's cropping of the nude body displaces the viewer's attention from the frontality of sex to the pictorial frame that cuts the body off—a feature shared by other works, such as Two Nudes (Deux Nus; 1910), and Red Nude. The effort to draw the spectator's attention to framing devices is deliberately underlined in Red Nude , where the profile of the crouching red nude breaking out of the frame of the painting also cuts into the frame of another painting. Located in the upper lefthand corner of the image, this painting is further disfigured by the painter's signature cutting across the head of a female figure. The authorial signature is displaced into a position where its nominal content interferes with the visual content and consumption of the image. Rather than merely stripping the nude, Duchamp begins to strip away the visual conventions that define the nude as a pictorial genre.

By 1910, Duchamp's exploration of the nude enters a new phase, one where issues of pictorial abstraction are reframed by their interplay with nominal expectations triggered by the title. Loosely identified as his "Symbolist" phase because of its visual affinities to the works of Paul Gauguin and Pierre Girieud, Duchamp's works betray the Symbolist conceit of combining word and image.[15] Duchamp challenges notions of visual and verbal reference by playing them against each other through puns. The doubling of female nudes in The Bush (Le Buisson ; 1910) (fig. 4) and in Baptism (1911) is underlined by framing of the figures by a shrublike halo, an aura that conflates their physical outline with the landscape that surrounds them. For Lawrence Steefel, The Bush "seems to point towards the ultimate goal of turning the world inside out."[16] This doubling and melding of background and bodily composition can be seen as a pun on the painting's title, The Bush , which nominally makes available the sexual referent that is traditionally dissimulated or visually veiled in the representation of nudity. Duchamp trivializes the visual referent by his puns on the title "bush," thereby defying the nominal expectations of the spectator as voyeur. In Paradise (Le Paradis; 1910) (fig. 5) the abject representation of the male and female nudes challenges the promissory tone of the title. There is no illumination nor spiritual "Ascension" here. The title Paradise contradicts the viewer's expectations, unless it is interpreted literally, as a pun on the French word paradis, which means no radiance, to be struck out, canceled, or just broken. The lack of radiance in Paradise

Fig. 5.

Marcel Duchamp, Paradise (Le Paradis), 1910. Oil on

canvas, 45 1/8 x 50 1/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

may reflect the fact that Symbolism as a pictorial style, rather than the painting's subject matter, has reached exhaustion.

While Duchamp admits in his interview with Cabanne: "I don't know where I had been to pick up on this hieratic business" (DMD , 23), this statement should not discourage us from considering this question. This halo effect or aura can be found in another work of this period entitled Portrait of Dr. R. Dumouchel (Portrait du Dr. R. Dumouchel; 1910) (fig. 6), where a nimbus surrounds the upper torso of the figure and, especially, the hands. Referring to this painting, Duchamp wrote in a letter to his patrons Louise and Walter Arensberg: "The portrait is very colorful (red and green) and has a note of humor which indicated my future direction to abandon mere retinal painting."[17] The note of humor that Duchamp evokes here may be a reference to the painting's caption "à propos de ta 'figure' mon cher Dumouchel" (loosely translated as, "by way of your 'appearance' my dear Dumouchel"). The word figure means figure, shape, or form, but its use by Duchamp suggests that it refers to Dumouchel's appearance: it is a reflection on the way he looks, his "air," or "aura." The colorful nature of this painting, its red and green colors, is a pun on color blindness. This pun on color blindness in the context of painting foreshadows, as it were, Duchamp's denunciation and subsequent aban-

donment of retinal painting. For Duchamp, the hieratic aura associated with Symbolist painting becomes the locus of investigation of the interplay of word and image, not under the guise of symbols but as puns.

This "halo" effect or aura continues to reappear throughout Duchamp's works, either as an analogy to smell (in such works as Fountain [1917] and Beautiful Breath, Veil Water [Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette; 1921]), or as an analogy for electricity (in Bec Auer [a gas lamp circa 1902]; The Large Glass [1915–23]; Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas (1946–66); and in a set of prints entitled The Bec Auer [1968]).[18] The word "aura" (in Greek, breeze or breath) signifies an influence or emanation issuing from the human body, although invisible to ordinary eyes and surrounding it as an atmosphere.[19] In Duchamp's later works the "aura" is deployed as a critique of painting as a visual event, in

Fig. 6.

Marcel Duchamp, Portrait of Dr. R. Dumouchel (Portrait Du

Dr. R. Dumouchel), 1910. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 25 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise

and Walter Arensberg Collection.

order to recover its intellectual potential. Considered from this perspective, Duchamp's early experiments with the hieratic can be understood as an allusion to the history of painting. This was at a time when the appearance of the nude, like painting itself, attained value by virtue of its religious, philosophical, and moral function, and was thus in excess of visual semblance. If painting exuded an "aura," this is because its significance was originally defined by its social rather than cultural function. The loss of painting's "aura" in the age of mechanical reproduction heralds the end of painting as a purely manual and visual event and its conceptual rebirth as a practice stripped of the hallowed echoes of visual semblance.[20] Duchamp's antiretinal stance reflects his effort to expand the meaning of painting by returning to a historical understanding of painting that takes into account its functional role. As Duchamp explains to Cabanne:

Since Courbet, it's been believed that painting is addressed to the retina. That was everyone's error. The retinal shudder! Before, painting had other functions: it could be religious, philosophical, moral. If I had the chance to take an antiretinal attitude, it unfortunately hasn't changed much; our whole century is completely retinal, except for the Surrealists, who tried to go outside it somewhat. And still, they didn't go so far! (DMD , 43)

In this context, painting is redefined: it is considered no longer merely visual/erotic stimulation but also conceptual intervention.

If Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (fig. 7) scandalized both the critics and the public alike, this is because it challenged the nominal expectations of the viewer more than any of Duchamp's previous works. Its rejection by the Salon des Indépendants in 1912, and the public furor occasioned by its exhibition at the New York Armory Show in 1913, are a barometer of the painting's transgressive character. Described as an "explosion in a shingle factory," Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was further humored by a cartoon depiction entitled Rude Descending a Staircase. The word rude appropriately captures the impact of the Nude, its deliberate disregard for the artistic conventions of the genre. This work scandalized not only the general public but also the avant-garde circles of the time. Duchamp withdrew his work from the Salon des Indépendants

Fig. 7.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Nu Descendant Un Escalier,

No. 2), 1912. Oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 35 1/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

by refusing to comply with Metzinger's and Gleizes's request to change the title because it was too "literary," in a caricatural sense. As Duchamp explains, the title plays a significant role in explaining the particular interest and impact of this work:

What contributed to the interest provoked by the canvas was its title. One just doesn't do a nude woman coming down the stairs, that's ridiculous. It doesn't seem ridiculous now, because it's been talked about so much, but when it was new, it seemed scandalous. A nude should be respected . (DMD, 44; emphasis added)

Duchamp's comments indicate that the reception of this painting was being filtered through a set of expectations, whose nominal character was staged by the title. The abstract nature of this work and thus its failure to provide a visual referent for the title only increased the public's disappointment. Nude. . . No. 2 presents a clash of nominal and visual expectations that are the expression of the history and conventions of painting. Instead of reclining passively, Duchamp's fractured nude is actively descending a staircase. The scandal surrounding the exhibition of Nude. . . No. 2 thus reflects the destruction of the nude as traditional subject matter of painting. In his book The Nude, Kenneth Clark maintains that the nude is not the starting point of a painting but a way of seeing that the painting achieves.[21] The nude embodies a set of representational strategies that imply a particular relation between the spectator and the spectacle of the body reduced toan image on display. Constructed as the subject of desire from the Renaissance to the late nineteenth century, the nude as a pictorial genre involves a structure of spectatorship that relies upon the objectification of the female body. This interplay of visual and nominal expectations staged by the nude as a pictorial genre was put into question by painters such as Edouard Manet, who in Olympia (1863) and Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe (1862–63) challenged the inscription of the desiring look of the spectator.[22] Moving away from figuration into abstraction, Duchamp's Nude. . . No. 2 further challenges this congruence of visual, nominal, and generic expectations.

The Nude. . . No. 2 reduces the anatomical nude to a series of successively fractured volumes: "Painted, as it is, in severe wood colors, the

anatomical nude does not exist, or at least cannot be seen, since I discarded completely the naturalistic appearance of a nude, keeping only the abstract lines of some twenty different static positions in the successive action of descending."[23] The renunciation of the naturalistic appearance of the nude in favor of its twenty positions in the successive act of descent reflects Duchamp's radical critique of painting through chronophotographic freeze-frame techniques.[24] What is at issue here is a challenge of the pictorial medium through sequential photography: a critique of vision as a cognitive medium that conflates spectatorship and pleasure. The splintering of vision into a series of frames that fragment and abstract both the identity of the nude and the process of movement inscribe into the painting an interval, a temporal dimension. Functioning neither descriptively nor prescriptively, the title Nude Descending a Staircase inscribes a temporal delay that interferes with the visual consumption of the image. This strategy of delay also redefines and defers notions of visual reference that are traditionally associated with photography. While appealing to techniques of mechanical reproduction, such as photography, to redefine the pictorial medium and its subject matter, Duchamp succeeds in redefining painting itself as a process whose plasticity includes temporal considerations.

Asked by Cabanne how did the painting originate, Duchamp responded:

In the nude itself. To do a nude different from the classic reclining or standing nude, and to put it into motion. There was something funny there, but it wasn't funny when I did it. Movement appeared like an argument that made me decide to do it.

In the "Nude Descending a Staircase," I wanted to create a static image of movement: movement is an abstraction, a deduction articulated within the painting, without our knowing if a real person is or isn't descending an equally real staircase. Fundamentally, movement is in the eye of the spectator, who incorporates it into the painting. (DMD, 30)

The picture presents the viewer with a "vertigo of delay," to use Paz's term, rather than one of acceleration.[25] Duchamp's interest in kinetics here is conceptual: the movement in the painting is produced through the

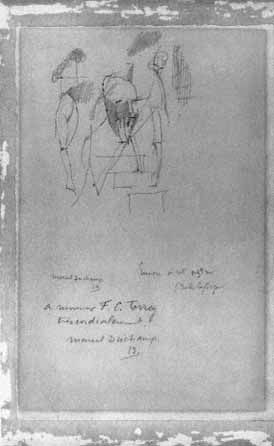

Fig. 8.

Marcel Duchamp, Once More to this Star (Encore

À Cet Astre), 1911. Pencil, 9 3/4 x 6 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

decomposition of the graphic elements. The staggered motion of the "nude" demonstrates an analysis of movement rather than the Futurist seduction with the dynamics of movement.[26] The kinetic character of the nude is not merely the thematization of movement as a pictorial fact but rather the discovery that the retinal is not an essential given but a rhetorical condition.

But why is the nude descending? This question is all the more interesting, since in its preliminary sketch Once More to This Star (Encore à cet astre; 1911) (fig. 8), based on the title of Jules Laforgue's poem, the primary figure is ascending a staircase. A network of visual puns connects Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 to Once More to This Star: instead

of ascending to a star, the star becomes a staircase for the obverse movement of descent. Duchamp explained his interest in Laforgue's poetry, particularly his prose poems Moralités Légendaires, in terms of their humor and poetic quality, as such: "It was like an exit from Symbolism" (DMD, 30). Just as Laforgue's poem denounces the idealist aspirations of Symbolist poetry by pointing out that the stellar image of the sun is undermined by its ordinary and pockmarked appearance, so does Duchamp transform the idealism that underlies pictorial praxis into a mere stair, a pun on the notion of descent understood both literally and figuratively.[27] The fact that the nude may be descending from its pedestal should be of no surprise, given that its ascension into a "genre" is ungendered by being at once sexually and pictorially redefined.

The ambiguous title of the Nude (nu, in French) gives no particular indication as to the referent's gender, although critics have identified it generically as female, de rigueur. Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 thus emerges as a critique of pictorial representation to the extent that it challenges the ideological underpinnings of the nude as a genre that is invariably femininely gendered. Unable to incarnate the nominal expectations of the spectator, the nude visually fractures the spectator's gaze by setting it into a spiraling motion. In doing so Duchamp points both to the title and to the spectator's gaze as the sites on which hinges the facticity of gender. This resistance to the equation of spectatorship with visual consumption and delectation is explicitly thematized in Duchamp's later works. In Selected Details After Courbet (Morceaux choisis d'après Courbet; 1968), for instance, the spectator's gaze is conflated with the falcon (faucon, inFrench: a pun on the facticity of sex) in the foreground, thereby revealing the role of language in the constitution of gender as sexual referent. The Nude 's descent thus functions as an index of Duchamp's strategic displacement and rethematization of the nude as a pictorial genre and its declension from the spectator's nominal expectations.

As a descendant from the lineage of painterly traditions, Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 stages both its genealogical derivation, as well as its own deviation from this ancestry. The descent of the Nude is not merely the mark of a genealogical decline but also the legal index of the passage of an estate through inheritance.[28] The Nude's

descent illuminates Duchamp's own inheritance of previous pictorial traditions and his efforts to literally draw on this heritage by reproducing it in new ways. Is it surprising then that Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is the first of Duchamp's serial works, having been preceded by Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1 (Nu descendant un escalier, no. 1; 1911) (fig. 9), only to be followed by Duchamp's full-sized photographic and hand-colored facsimile entitled Nude Descending a Staircase, No.3 (Nu descendant un escalier, no.3; 1916). As Joseph Masheck notes: "Typical of Duchamp is this work's self-illustrative and self-reproductive function, as well as the fact that as an actual photograph it returns to one of the technical sources of the 'original' painting."[29] The self-illustrative and self-reproductive aspects of Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase demonstrate his efforts to redefine the notion of pictorial production, as a genealogical intervention based on reproduction.

However, this reproductive industry did not stop short with the fullsized versions of the Nude. This work was further reproduced as a miniature pencil-and-ink drawing Nude . . . No. 4 (1918) for the dollhouse of Carrie Stettheimer. This doll-sized version of the Nude was followed by further miniature reproductions in The Box in a Valise (1938–41). From a single work that is by definition a multiple, insofar as it is part of a series, Duchamp generates an entire corpus. By discovering the self-productive and self-reproductive potential of the Nude, Duchamp redefines the nude as a medium of and for reproduction. Eroticism in this context no longer refers to the visual appearance of the nude but instead functions as an index of its proliferation as modes of appearance. Duchamp challenges the eroticism traditionally associated with spectatorship and voyeurism by proposing an alternative eroticism whose speculative, technical, and humorous character restages through reproduction the notion of artistic creativity and production.

Given Duchamp's explicit rejection of the equation of vision and eroticism, how are we to explain his interest in the nude as pictorial genre? It seems that the entire trajectory of his life's work is defined by the arching movement from Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 to The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, and culminating in his testamentary work Given: 1) the waterfall, 2) the illuminating gas. While Duchamp maintains that eroticism is the only -ism he believes in, it is

clear that eroticism for him is not linked to an anatomical or essentialist destiny but rather, like humor, it is defined through movement, as transition instead of stasis. Eroticism in the figurative arts is most commonly represented as the relationship between clothing and nudity, and thus, as Mario Perniola suggests, it is conditional on the possibility of movement or transition from one state to another.[30] For Duchamp, however, eroticism signifies conceptually and philosophically as a reflection on representation, a presentation understood in the mode of reproduction, where appearance is the result of repeated modes of impressions.

Now we begin to understand the conceptual import of both engraving and cartooning in Duchamp's work. Engraving is one of the earliest forms of mechanical reproduction that involves a different way of conceiving

Fig. 9.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 1

(Nu Descendant Un Escalier, No. 1), 1911. Oil on

cardboard, 38 1/8 x 23 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and

Walter Arensberg Collection.

the plastic image. Not only is the appearance of the engraved image the result of multiple reproductions but its very identity is defined as a technical process, involving multiple impressions or imprints. An engraving is a template, a sculptural mold that functions like a photographic negative. Engraving as a medium challenges the autonomy of the pictorial image, insofar as the image acts as a temporal record of multiple impressions.[31] Although associated historically with craft rather than art, engravings challenge both the uniqueness of the plastic image and traditional notions of artistic creativity. Duchamp's pictorial series of Nude Descending a Staircase, as a multiple that undergoes extensive reproduction, illustrates the logic of engraving operative in his works. This is not to say that these works are engravings, since they are clearly paintings; rather, the conditions of production and reproduction evidenced in these series suggest conceptual processes akin to those involved in the technical reproduction of engravings.

You may ask how cartoons inform Duchamp's oeuvre? The answer by now is clear. Regarded as a form of popular art associated with the print medium, cartoons are images that are constructed like rebuses, as composites of language and image. Their humor is not just visual but intellectual. They are often visual analogues of linguistic puns. This is not to suggest, however, that Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is merely a cartoon, a rude joke at the expense of painting. Rather, Duchamp's use of the title as nominal intervention in order to restage the expectations of the spectator reframes the reception of this work as an intellectual, instead of a purely visual, experience. Consequently, despite its mechanomorphic character, Duchamp's Nude can also be seen an an "anti-machine." As Octavio Paz explains: "These apparatuses are the equivalent of the puns: the unusual ways in which they work nullify themselves as machines. Their relation to utility is the same as that of delay to movement;they are without sense and meaning. They are machines that distill criticism of themselves."[32] If the Nude is an elaborate visual and linguistic pun, where exactly is the joke? As this study has suggested, Duchamp's humor lies in redefining the visual image as a serial imprint, as a construct where appearance does not refer to an external reality but to a mode of production whose logic is reproductive. Duchamp doubly displaces painting: first, by redefining it through the logic of engraving, as a print medium, and second, by draw-

ing on the linguistic and intellectual logic of cartooning in order "to put painting once again at the service of the mind."[33] Eroticism in this context is no longer defined as a transitional movement between clothing and nudity. Instead, it becomes the rhetorical interplay between language and vision, which constructs the facticity of gender as a pun.

The Mainspring of the Future: Playing the Field

While all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.

—Marcel Duchamp

When asked by Katherine Kuh, one of his interviewers, which of his works he considers to be the most important, Marcel Duchamp replied:

As far as date is concerned I'd say the Three Stoppages [3 stoppages étalon ] of 1913. That was really when I tapped the mainspring of my future. In itself it was not an important work of art, but for me it opened the way—the way to escape from those traditional methods of expression long associated with art. I didn't realize at that time exactly what I had stumbled on. When you tap something you don't always recognize the sound. That's apt to come later. For me the Three Stoppages was a first gesture liberating me from the past.[34]

As Duchamp subsequently explains, the idea of letting a piece of thread fall on a canvas was accidental, but "from this accident came a carefully planned work."[35] What exactly did Duchamp stumble on that enabled him to escape the traditional means of expression associated with art? Was it the idea of chance, or its plastic deployment and embodiment as an event or work? Before exploring in more detail the role of Three Standard Stoppages (3 stoppages étalon; 1913–14) as a gesture that would liberate him from the past, one must first understand how this work emerges out of Duchamp's pictorial experiments, for this work decisively signifies both his break with painting and his strategic turn toward the ready-mades and The Large Glass.

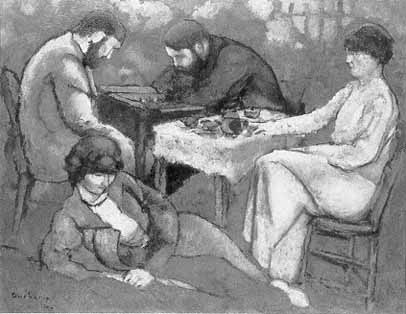

Duchamp's interest in chance as a way of redefining conventional forms of artistic expression appears early on in his paintings and is tied to his interest in chess. For Duchamp, chess is not merely a pastime or an ordinary game because its intellectual character represents for him a plastic

Fig. 10.

Marcel Duchamp, The Chess Game (Le Jeu D'échecs), 1910. Oil on canvas,

44 7/8 x 57 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter

Arensberg Collection.

Fig 11

Paul Cézanne, Card Players, 1892.

Courtesy of The Courtauld Institute Gallery, London.

and thus, by extension, an artistic dimension. As a strategic game that requires the interplay of two opponents, chess provides Duchamp with a new way of envisioning art in its dialogue with the tradition. The analogy of art and chess enables Duchamp to appropriate chance and redefine its plastic impact in a field of already given determinations. Starting with The Chess Game (Le jeu d' hecs; 1910) (fig. 10), and continuing through 1911, Duchamp produces a series of works dealing with chess. These include six drawings/sketches, which culminate in the painting Portrait of Chess Players (Portrait de Joueurs d'échecs; 1911).[36] These works range from a relatively conventional depiction of a chess game, to progressively more abstract renditions of the players, the board, and the chess pieces.

Duchamp's lifetime interest and preoccupation with chess is well known, but its significance and precise impact on his art is less recognized.[37] While Duchamp openly acknowledges his indebtedness of The Chess Game to Paul Cézanne's Card Players (1892) (fig. II), it is clear that he is already playing another game (DMD, 27). In The Chess Game the centrality of the table in Cézanne's Card Players is displaced on a diagonal axis along which there are two tables, one with a chessboard on it and another set in the manner of a still life.[38] Duchamp's choice to replace the card game with a chess game makes visible something that would otherwise remain invisible: the chessboard as a metaphor for the mental ground rules that define it as a game. The checkered pattern of the board, however, is also an allusion to another set of rules, those of Albertian perspective that have guided the development of painting.[39] This allusion is reinforced by the fact that the chess players are Duchamp's brothers, who are both practicing artists. If we pursue Duchamp's analogies in The Chess Game, art no less than chess emerges as a strategic, rather than purely plastic, domain. Both chess and perspective are systems whose normative standards prescribe and determine the nature of representation. What had been originally conceived as an arbitrary relation between painting and the world is now revealed to be a strategic, albeit conventional game, a chess game.

Why, you may ask, did Duchamp choose not merely to reshuffle Cézanne's cards but to play a different game altogether? The answer lies in his understanding of chess as a plastic, rather than a purely intellectual, game. As Duchamp's comments to James Johnson Sweeney indicate, playing

chess is like painting insofar as "it is like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind" (WMD, 136). This plasticity, however, is not in the realm of the visible but in the abstraction of the movement of pieces on the board. In his interview with Francis Roberts, Duchamp explains how the strategic and positional nature of chess generates plastic effects:

In my life chess and art stand at opposite poles, but do not be deceived. Chess is not merely a mechanical function. It is plastic, so to speak. Each time I make a movement of the pawns on the board, I create a new form, a new pattern, and in this way I am satisfied by the always changing contour. Not to say that there is no logic in chess. Chess forces you to be logical. The logic is there, but you just don't see it.[40]

The plasticity that Duchamp ascribes to chess is not aesthetic in the visual sense but rather intellectual. The movement of the pieces on the board creates patterns and forms whose contours are constantly shifting. This moving geometry is described by Duchamp as "a drawing" or as a "mechanical reality" (DMD, 18). As Duchamp elaborates: "In chess there are some extremely beautiful things in the domain of movement, but not in the visual domain. It's the imagining of the movement or the gesture that makes the beauty, in this case. It's completely in one's gray matter" (DMD, 18). The beauty that Duchamp appeals to is not one based on aesthetic categories, on visual appearance and artistic self-expression. Rather, the beauty in question is defined by the plasticity of the imagination, by the poetry of its ever changing contours.

The analogy of chess and art is one that is mediated by an allusion to the abstract nature of both music and poetry. As Duchamp explains:

Objectively, a game of chess looks very much like a pen-and-ink drawing, with the difference, however, that the chess player paints with black-and-white forms already prepared instead of having to invent forms as does the artist. The design thus formed on the chessboard has apparently no visual aesthetic value, and it is more like a score for music, which can be played again and again. Beauty in chess is closer to beauty in poetry; the chess pieces are the block

alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chessboard, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem. Actually, I believe that every chess player experiences a mixture of two aesthetic pleasures, first the abstract image akin to the poetic idea of writing, second the sensuous pleasure of the ideographic execution of that image of the chessboards.[41]

Relying on analogies to the media of music and poetry, Duchamp uses chess as a way of expanding the meaning of art. No longer bound to the creation or invention of visual forms, the chess player "paints" with already given black-and-white forms. The interest of the exercise lies in the composition of the design, a visual score that is open to multiple performances, for the nature and value of chess exists only as a performance, a duet where two interpreters put their heads together, so to speak. The chess pieces in this game function as linguistic elements already given by convention, but ready to be redeployed poetically in new ways. While subject to particular rules governing the possibility of movement, the mechanisms generated, as the "ideographic execution of that image," are always open to further reinterpretation. Thus Duchamp uncovers within chess a paradigm for the reinterpretation of aesthetic pleasure as a pleasure derived neither from invention nor the sensuality of the pieces themselves, but from their recomposition and poetic deployment as a game.

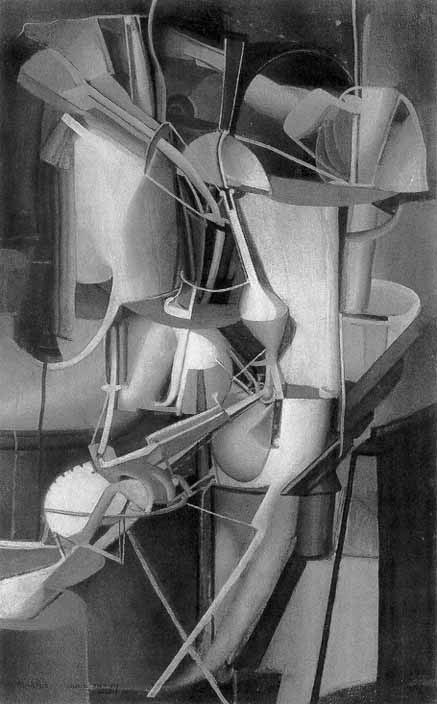

Is it then surprising that the later versions of The Chess Game, including the pen-and-ink drawings/sketches that culminate in the highly abstracted painting Portrait of Chess Players (fig. 12), represent a visual decomposition of the image in terms of the chessboard? Another painting from this period, Yvonne and Magdeleine (Torn) in Tatters (Yvonne et Magdeleine déchiquetées; 1911) (fig. 13), representing Duchamp's sisters, provides one with some verbal clues in regards to the mechanics of these images. The expression "torn in tatters" (déchiqueter, in French) means to hack, slash, tear to shreds, or tear up. As Duchamp explains to Cabanne, "this tearing was fundamentally an interpretation of Cubist dislocation" (DMD, 29). The word for tearing (déchiqueter, however, is also a pun on chessboard or checker pattern (ßchiquier, in French). Rather than interpreting this tearing as Cubist dislocation, Duchampis reinterpreting Cubism itself conceptually from the perspective of chess, as a game whose

Fig. 12.

Marcel Duchamp, Portrait of Chess Players

(Portrait de Joueurs D'échecs), 1911. Oil on

canvas, 42 1/2 x 39 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Fig. 13.

Marcel Duchamp, Yvonne and Magdeleine (Torn)

Tatters (Yvonne et Magdeleine Déchiquetées), 1911.

Oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

illogical visual character becomes legible once seen from the perspective of chess. More specifically, the serial fragmentation and multiplication of the protagonists into shards, while depersonalizing them into mechanical patterns, illuminates painting in a new light. Duchamp visibly draws on Cubism, only to redefine its logic as a representation: the dislocations visible in the image are but the diagrams of movements ideographically transposed from chess.

While such an interpretation seems to force Duchamp's hand, as it were, it is important to recall Duchamp's comment to Cabanne regarding the fact that Portrait of Chess Players was painted not in ordinary light, but by gaslight:

This "Chess Players," or rather "Portrait of Chess Players," is more finished, and was painted by gaslight. It was a tempting experiment. You know, that gaslight from the old Aver jet is green; I wanted to see what the changing of colors would do. When you paint in green light and then, the next day, you look at it in day light, it's a lot more mauve, gray, more like what the Cubists were painting at the time. It was an easy way of getting a lowering of tones, a grisaille. (DMD, 27).

Duchamp's innovative use of a green gaslight as a way of lowering the color tones of this painting (grisaille, in French and in English) also func-

tions as a way of illuminating it from a conceptual or mental perspective (a pun on matière grise, in French). Rather than merely seeking to reproduce Cubist colors, Duchamp uses the "gas" light as a pun that reframes the notion of pictorial "gaze." The title Portrait of Chess Players alerts the viewer to the mise-en-abyme representational nature of this work: its visual character is mediated conceptually: "it's light that illuminated me" (DMD, 27). Duchamp's portrait (pourtraire, in French, from Latin, pro [forth] and trahere [to draw]) draws upon and restages earlier versions of chess games and chess players by redefining the meaning of pictorial representation as a practice that is not merely visual but also mental.

If the sequence of paintings and sketches from The Chess Game to Portrait of Chess Players represents Duchamp's artist brothers playing chess, in later paintings the chess pieces themselves become the subject matter of art. They take over the board, as it were. Having uncovered the affiliation between art and chess by revealing their shared strategic and positional nature, Duchamp now proceeds to examine the plastic dimension of the mechanics of strategy. As Duchamp observes: "In chess, as in art, we find a form of mechanics, since chess could be described as the movement of pieces eating one another."[42] This analogy highlights another aspect of chess—its adversarial nature—which is equally applicable to art, for Duchamp's own effort to rethink painting means devising new strategies for an old game. Whether his adversaries may be his own brothers, who were also artists, or artistic movements such as Cubism, Duchamp's understanding of art as a strategic game enables him to redefine the notion of artistic creativity as a form of production based on reproduction. Duchamp's redefinition of art in terms of chess involves, on the one hand, accepting one's affiliation to traditions, that is, the readymade character of pictorial convention, and on the other hand, the effort to redraw the board in order to radically rethink the terms of the game. Consequently, artistic innovation is freed from the "anxiety of influence," since tradition itself provides conventional or ready-made elements that Duchamp can redeploy in a strategic fashion.[43]

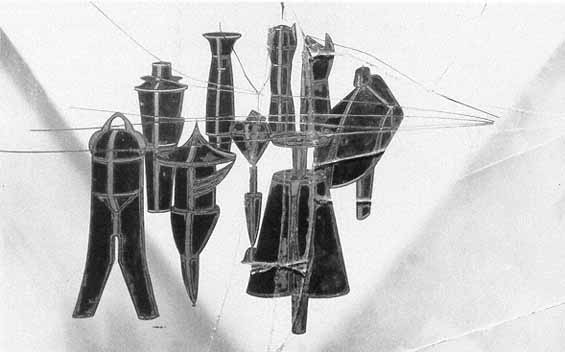

Following Portrait of Chess Players and Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Duchamp produces a set of sketches and paintings whose mechanomorphic appearance is underlined by titles that pursue chess analogies. Among the most significant are The King and Queen

Surrounded by Swift Nudes (Le Roi et la Reine entourés de nus vites; May 1912) (fig. 14) and The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride (Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée; 19) (fig. 15), the latter being one of the preliminary works to The Large Glass. According to Duchamp, the title "'King and Queen' was once again taken from chess, but the players of 1911 (my two brothers) have been eliminated and replaced by the chess figures of the King and Queen."[44] In the case of The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride, the chess analogy is embedded in the notion of marriage implicit in the transformation of the virgin into the bride. In some card games, pinochle for instance, the term marriage refers to the combination of the king and queen of the same suit. In these paintings we are witnessing the passage from chess analogies into works whose diagrammatic character begins to challenge the very limits of art.

The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes was painted on the back of an earlier painting, Paradise, which was turned upside down. Commenting on this work to Katherine Kuh, Duchamp notes:

You know this was a chess king and queen—and the picture became a combination of many ironic implications connected with the words "king and queen." Here the "swift nudes," instead of descending, were included to suggest a different kind of speed, of movement—a kind of flowing around and between the two central figures. The use of nudes completely removed any chance of suggesting an actual scene or an actual king and queen.[45]

The irony in question here involves the substitution of chess pieces for the traditional subject matter of painting, which as reproductions put into question the referential status of painting. His choice of renaming the nudes in terms of their quality or agility of movement was "literary play," a way of transposing sport terminology into painting.[46] The juxtaposition of the king and queen with the "swift nudes," which are reproductions of Duchamp's earlier descending nudes, redefines painting itself as a space of reproduction, where visual appearance is merely the diagrammatic record of various transitions.

When discussing the relation of Nude Descending a Staircase and The King and Queen Traversed by Swift Nudes (Le Roi et la Reine traversés

par des nus vites; April 1912), Duchamp describes it as minimal, except that they share "the same form of thought": "as for the swift nudes, they were the trails which crisscross the painting, which have no anatomical detail, no more than before" (DMD, 35). The introduction of speed into these paintings is not merely a concession to Futurism but rather the affirmation of the affinity between art and chess. If playing chess is like designing or constructing a mechanism, then art becomes a way of setting this mechanism into motion strategically. Instead of visually representing motion, Duchamp, following Marey's chronophotographic techniques, maps it as a "system of dots delineating different movements" (DMD , 34). He thus reduces the intervention of vision by demonstrating that all the visible traces are but forms of ideographic mapping. By interpreting painting as a conceptual intervention that converts visible objects into cartographic networks, Duchamp redefines painting as a philosophical enterprise. As Octavio Paz observes:

Fig. 14.

Marcel Duchamp. The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (Le Roi et la Reine

Entoures de Nus Vites), 1912. Oil on canvas, 45 1/8 x 50 1/2 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

Fig. 15.

Marcel Duchamp, The Passage from the Virgin to the Bride

(Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée), 1912 Oil on canvas,

23 3/8 x 21 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In these canvases the human form has disappeared completely. Its place is not taken by abstract forms but by transmutations of the human being into delirious pieces of mechanism. The object is reduced to its most simple elements: volume becomes line; the line a series of dots. Painting is converted into a symbolic cartography; the object into idea. It is not the philosophy of painting but painting as philosophy.[47]

The painting The passage from the Virgin to the Bride (fig. 15) thus literalizes a transition that Duchamp is effecting from visual to conceptual painting. The resonant tension that this work sustains between abstraction and figuration is amplified by the punning echoes of the title. Itself a transitional work, between two preliminary sketches Virgin No. 1 and Virgin No. 2 , this painting is a study for the final painting of Bride (Mariee; 1912) (fig. 16). The "passage" in question here refers both to the intermediary status of this work and, more importantly, to the redefinition of painting itself as a transitional activity, a "rite of passage" of sorts.

Fig. 16.

Marcel Duchamp, Bride (Mariee), 1912. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 x 21 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.

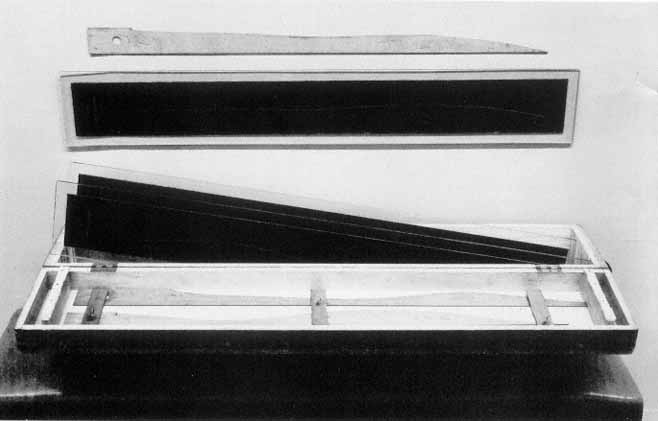

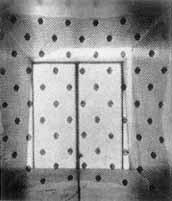

Fig. 17

Marcel Duchamp, Three Standard Stoppages (3 Stoppages Étalon), 1913–14. Semi-Ready-Made Three Threads, one meter in

length, dropped from a height of one meter and glued to preserve their outline onto a canvas painted Prussian blue. The canvas

was cut into three strips (47 1/4 x 5 1/4 in .), which were then glued onto three glass panels (49 3/8 x 7 1/4 in.) ) Three flat wooden

strips (47 x 2 3/8 in; 42 7/8 x 2 1/2 in ., and 43 1/2 x 2 1/2 in) were cut to repeat the curves of the threads. The entire assembly is

enclosed in a wooden box (50 7/8 x II x 9 1/8 in .)

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Katherine S. Dreier Bequest

If engraving has enabled Duchamp to conceive painting itself as a transitional activity, as a set of impressions or imprints, chess enables him to redefine it strategically. From the chess Queen of King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes, Duchamp now stages the process of becoming painting, the passage from visual ("Virgin") to conceptual ("Bride") painting. As Thierry de Duve observes: "the painting does what it says, and says what it does," but in so doing it opens up the space for a new kind of passage, away from painting altogether.[48] By visibly deploying the strategies that define painting, Duchamp effectuates a climactic passage through painting that opens up the possibility of resituating artistic activity within a terrain that no longer requires the confines of the pictorial space or the handiwork of the brush. The nuptial rites that The PASSAGE from the Virgin to the Bride initiates and enacts by covenant involve the redefinition of both painting "the Bride" and the painter, as "the groom." Duchamp, however, is no ordinary groom in the sense of assuming the position of a liveried servant, that is, an inferior attendant in relation to painting. His job is not that of an ordinary groom—merely to equip, prepare, or dress up painting—but rather, equipped with the insights that painting provides, he draws on painting in order to redefine the meaning of art.

Given Duchamp's exploration of the limits of painting as a kind of end game (to use an expression that is common in chess), it is not surprising that by 1913 he begins to envisage leaving it behind altogether. He starts experimenting with chance operations, which, while drawing on pictorial traditions, also announce his future discovery of the ready-mades. As Duchamp himself noted, Three Standard Stoppages (fig. 17) represents a radical turning point in his work, marking his abandonment not only of painting but also of the conventional notions of art. This work is an assemblage (a semi-ready-made) consisting of a croquet box that contains three separate measuring devices that were individually formed by chance operations. Three different threads, one meter in length, were dropped (or allowed to fall freely, depending on one's perspective) onto a canvas painted Prussian blue, and glued into place. The resulting impressions, capturing the curved outline of their chance configurations, were then permanently affixed to glass plate strips. These plates served as imprints for the preparation of three wood templates.

Designated as an instance of "canned chance," this work is also categorized by Duchamp as "a joke about the meter."[49] Francis M. Naumann concludes that "the central aim of this work was to throw into question the accepted authority of the meter," as a standard unit of measurement.[50] Duchamp's own description of this work, as "three meters of thread falling and changing the shape of the unit of length," verifies Naumann's contention with a twist. Not only does Three Standard Stoppages distort the length of the meter through curvature but in doing so, it demonstrates the recognition that the meter itself as a unit of length is generated through approximation: the straightening out, as it were, of a curved meridian.[51] Duchamp sets the viewer straight by graphically showing that the authority of the meter as a measuring device relies upon distortions that he corrects through chance operations.

While this work may parody the authority of the meter, and thus by extension challenge notions of authority in general, it is less clear whether it reflects Duchamp's effort to champion individual rights, as Naumann claims.[52] As a quasi-scientific device, Three Standard Stoppages draws on the authority of a scientific standard, only to uncover its arbitrary and institutionally sanctioned character. Duchamp's invocation of chance is not a strategy to personalize the laws of physics but merely to ironically "strain" its laws in order to reveal their instability. As he explains:"I was satisfied with the idea of not being responsible for the form taken by chance."[53] Chance suspends the notion of personal responsibility by redefining the notion of artistic creativity as a form of production whose plasticity is contingent rather than deliberate.

Duchamp's experiment with "canned chance" not only questions scientific authority but also notions of artistic authority, which by their embedded and ingrained character reduce art to a mechanical practice. Roberts's question whether the dependence on chance betrays a disdain for the mechanics of art, leads Duchamp to respond:

I don't think the public is prepared to accept it . . . my canned chance. This depending on coincidence is too difficult for them. They think everything has to be done on purpose by complete deliberation and so forth. In time they will come to accept chance as a possibility to produce things. In fact, the whole world is based on

chance, or at least chance is a definition of what happens in the world we live in and know more than any other causality.[54]

The notion of coincidence challenges through its arbitrary logic both personal and institutional forms of determinism. More important still, it puts into question the voluntaristic and intentional logic that defines the creative act and the identity of the artist. To assume chance as a locus for production is to understand causality itself not as an origin but as a productive event, whose plasticity can redefine the notion of artistic creativity.

While Three Standard Stoppages captures the "form taken by chance," it does so not as a unique event but as a series of impressions that are recorded first on canvas, then on glass, only to become the molds for a set of wood templates. The first set of chance operations is twice reproduced, each time redrawing the meter and reshaping it as the unit of length. The systematic transposition of the impression of the string to the painterly surface, which is affixed to glass, becomes like a printing plate that generates the outline of wood templates as its photographic negative. In this work we begin to witness the stripping bare of painting, the reduction of its operations to chance understood as a mode of production that relies on "mechanical" conventions. Under the rubric "The Idea of Fabrication," Duchamp discusses the compositional strategies of this work: "3 patterns obtained in more or less similar conditions: considered in their relation to one another, they are an approximatereconstitution of the measure of length" (WMD , 22). Chance deployed as a strategic set of operations replaces the notion of pictorial composition by that of fabrication, a mode of production defined by reproduction.

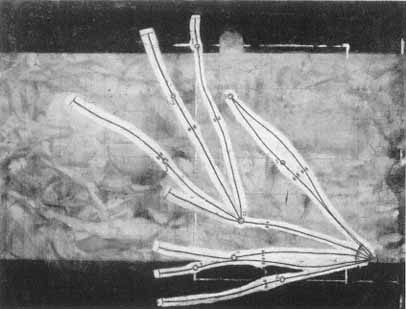

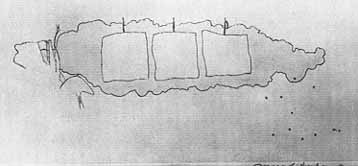

When Duchamp playfully suggests that Three Standard Stoppages may be a "joke about the meter," he also opens up the possibility that the meter in question may involve a poetic and musical referent, rather than a purely metric one.[55] In poetry the meter is not a unit of length but is instead an indicator of rhythm: a measured arrangement of a line of verse, or groups of syllables, having a time unit and regular beat. This may explain why Duchamp in the Box of 1914 refers to Three Standard Stoppages as "the meter diminished" (WMD, 22). Duchamp's efforts to "diminish" the meter are visible in his musical experiment Erratum Musical (from The Green Box; 1934) (fig. 18), which lacks both time signatures and measure markers.

Fig. 18

Marcel Duchamp, Erratum Musical, from The

Green Box, 1934 8 x 10 in

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection

As Carol P. James explains: "To bend meter in music, Erratum actually straightened it out, giving each note the same time value. Having no difference of length in relation to each other, the notes have no real time at all; all are equally hollow."[56] Just as Duchamp straightened out our idea of the meter, so does Duchamp in Erratum bend the notion of musical meter, by straightening it out and thus reducing it to meaninglessness.

In his Erratum Musical Duchamp sets to music a randomly chosen dictionary definition of the verb "to print": "Make an imprint mark traits a figure on a surface print a seal on wax" ("Faire une em-prein-te mar-quer des traits u-ne fi-gure sur une sur-face im-pri-mer un sceau sur ci-re" ).[57] This definition of printing as a mode of impression also alludes to the fate of music in the modern age, the fact that early recordings of sound were made in wax. As James observes: "The text of the Erratum cannily repeats the processes of reproduction of meaning, be they the printing of alphabetic letters, the visual traces codified as representations of meaning, i.e., writing, or do-re-mi (mi sol fa do ré) of the musical code recorded in

wax."[58] This insistence on printing as a recording device captures its affinity with music as a medium that generates "meaning" through successive reproductions. Whether it is a question of a figure or a melodic line, representation in prints or in music challenges conventional modes of artistic creativity, since meaning is constructed reiteratively and successively, rather than in the sweep of an off-handed manner.

Following Three Standard Stoppages, Duchamp transposes his experiments with chance operations back onto one of his last pictorial works entitled Network of Stoppages (Réseaux des stoppages étalon; 1914) (fig. 19). This work marks Duchamp's effort to contextualize chance not merely as an event but as a set of reiterative impressions whose plasticity is diagrammatic—a cartographic network. It involves the mirrorical return onto painting of chance operations exercised in Three Standard Stoppages. Using an already painted vertical canvas, Duchamp rotates it horizontally, divides it into two sections, and lightly repaints over the right section in white wash. This gesture anticipates his sectioning into two regions that we later find in The Large Glass. Duchamp remaps on the surface of an

Fig. 19

Marcel Duchamp, Network of Stoppages (Réseaux des Stoppages Etalon),

1914. Oil and pencil on canvas, 58 5/8 x 77 5/8 in.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

already given painting, a set of bifurcating lines and angles that redefine the painting as symbolic cartography. He redeploys chance operations by drawing upon painting, only to redraw painting itself according to the plastic logic of the network stoppages. Proceeding from chance understood as a stopgap measure, Duchamp generates a set of imprints whose reproductive character serves to redefine the originality of pictorial practice.

Through the Looking Glass

His [Duchamp] finest work is his use of time.

—Jean-Pierre Roché

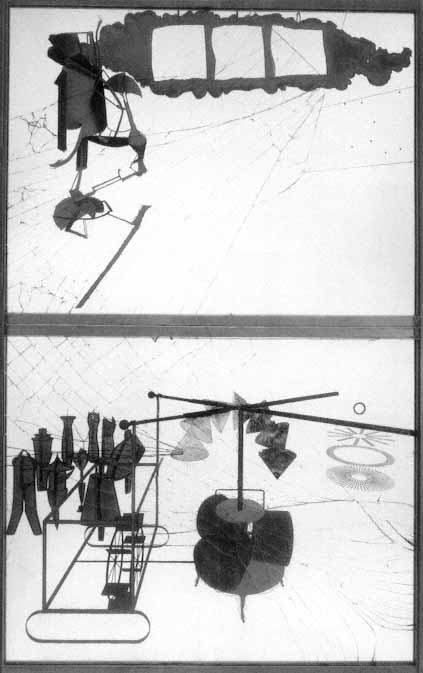

In the wake of his pictorial efforts and concomitant with the discovery of the ready-mades, Duchamp began a series of sketches and works that culminate in the production of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, also known as The Large Glass (figs. 20, 21). The sheer duration of this work (which took eight years to evolve and was "finally unfinished" in 1923) and its accidental completion (it cracked in 1926 while in transit from its first public showing to its owner Katherine Dreier), reveal the magnitude of Duchamp's desire to leave traditional forms of art behind.[59] As he explained to Cabanne: "Art was finished for me. Only the 'Large Glass' interested me." (DMD, 41). Considered as Duchamp's major opus, this work has elicited enormous critical reflection and engendered many debates in regard to its meaning and significance. As Calvin Tomkins observes:

The Large Glass stands in relation to painting as Finnegan's Wake does to literature, isolated and inimitable; it has been called everything from a masterpiece to a tremendous hoax, and to this day there are no standards by which it can be judged. Duchamp invented a new physics to explain its "laws," a new mathematics to fix the units of measurement of the new physics, and a condensed, poetic language to formulate its ideas, which he jotted down on scraps of paper as they occurred to him and stored away in a green cardboard box for future reference.[60]

Despite its visual transparency, or perhaps because of it, this work continues to resist definitive critical appropriations. Like the viewer's body, which is inscribed in this work as the tain, or silver backside, of a mirror, this

work's opacity most often reflects the presuppositions of the critical discourses that have sought to illuminate it.[61] My purpose in this study is not to provide a definitive account of The Large Glass, since it may be impossible to do so, but rather to use it as a vehicle, as a looking glass—a context for understanding Duchamp's particular passage through art as he explores the very limits of its conditions of possibility and its potential future.

When challenged by Pierre Cabanne to provide his own interpretation of The Large Glass, Duchamp responded:

I don't have any, because I made it without an idea. There were things that came along as I worked. The idea of the ensemble was purely and simply the execution, more than descriptions of each part in the manner of the catalogue of the "Arms of Saint-Etienne." It was a renunciation of all aesthetics in the ordinary sense of the word . . . not just another manifesto of new painting. (DMD , 42)

Duchamp's reluctance to provide an interpretation of his own work should not be understood as a mere refusal, as evasiveness, or as a sign of the work's intelligibility. Rather, Duchamp's statement repositions the significance of this work as a process: a repository of meaning not as given but as generated by the spectator through his or her active interplay with the work. The idea of this work does not function as a mere blueprint; rather, the logic of the ensemble emerges through the execution and assemblage of its specific elements. Using the analogy to the Arms of Saint-Etienne (the early twentieth-century French equivalent of a Sears and Roebuck catalog), Duchamp underlines the encyclopedic character of this work, as well as its ready-made logic.[62] By referring to a logic of assemblage whose nature is not artistic but technical and commercial, Duchamp is able to enact his renunciation of traditional aesthetics. His insistence that this work does not represent "just another manifesto of new painting," marks his effort to redefine aesthetics by invoking the mechanical logic of media of mass production, such as printing, engraving, and photography. The Large Glass thus represents "a sum of experiments," without the idea of creating yet another movement in painting, in the sense of Impressionism, Fauvism, or, for that matter, the contemporary Cubist and Futurist avant-gardes of the period.

Fig. 20.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, or The Large

Glass (La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, Méme), 1915–23. Oil,

varnish, lead foil and wire, and dust on glass mounted between two glass panels,

9 ft. x 1 1/4 in. x 5 ft, 9 1/4 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Katherine S. Dreier Bequest.

Fig. 21.

Diagram based on Marcel Duchamp's etching, The Large Glass Completed, 1965.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

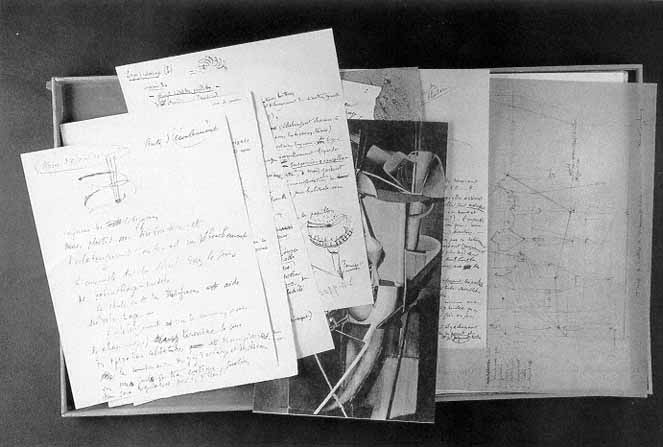

The idea of the glass as a compendium of experiments is further compounded by the fact that the spectator's visual experience of it is intended to be mediated by the intervention of Duchamp's notes in a box. As he explains to Cabanne:

For the "Box" of 1913–1914, it's different. I didn't have the idea of a box as much as just notes. I thought I could collect, in an album like the Saint-Etienne catalogue, some calculations, some reflections, without relating them. Sometimes they're on torn pieces of paper. . . . I wanted that album to go with the "Glass," and to be consulted when seeing the "Glass" because, as I see it, it must not be "looked at" in the aesthetic sense of the word. One must consult the book, and see the two together. The conjunction of the two things entirely removes the retinal aspect that I don't like. It was very logical. (DMD, 42–43)

The notes, calculations, and speculations that are part of the "Box" constitute a catalog, an arbitrary inventory of items to be consulted when looking at The Large Glass. The conjunction of written and visual information disrupts the visual consumption of the Glass by interfering with its "retinal" character. The act of vision is contextualized, thereby redefining the aesthetic autonomy of the Glass . As Duchamp explains: "The Glass is not to be looked at for itself but only as a function of a catalogue that I never made."[63] Although Duchamp did not produce an actual catalog to accompany The Large Glass, his comment indicates that the Box of 1914 (Boîte de 1914 ; 1913–14) (fig. 22) is intended to serve as its companion piece.[64] By designating the Box of 1914 as a kind of manual to the Glass , Duchamp emphasizes the conditions of its production. In doing so he removes the Glass from the aesthetic realm by introducing technical considerations. By mediating the perception of the Glass through the Box of 1914, Duchamp redefines the Glass not as an object in its own right but as a prototype, a blueprint of sorts, whose function is to redefine through industry the very meaning of art.

Duchamp's appeal to mechanical drawing as a way of challenging painting is a "reaction against the easy splashing way," reflecting his continued struggle: "I was fighting against the hand."[65] Considered in

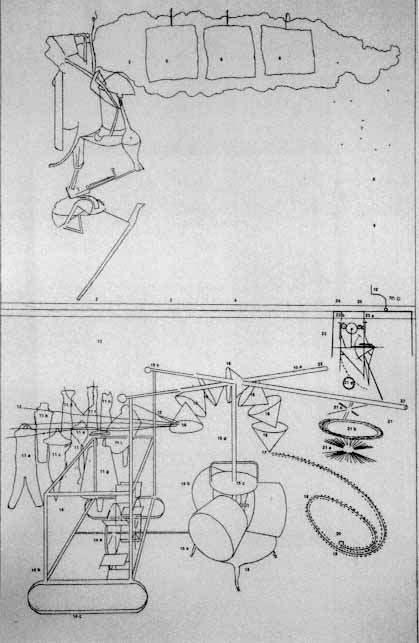

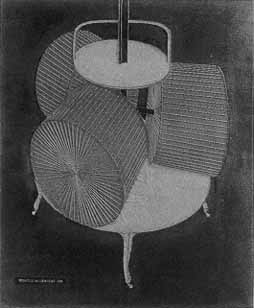

Fig. 22.

Marcel Duchamp, The Box of 1914 (Boîte de 1914), 1913–14.

Kodak photographic box containing sixteen photos of manuscript

pages and one of the design. To Have the Apprentice in the Sun,

9 7/8 x 7 1/4 in. Galleria Schwarz, Milan, Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Fig. 23.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataries,

Même) from The Green Box, 1934. 8 x 10 in.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg

light of the Box of 1914, and the subsequent Green Box (1934) (fig. 23), which bears the same title as The Large Glass (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), the Large Glass emerges as a compilation of various forms of mechanical reproduction, a work whose transitional status reflects Duchamp's efforts to challenge pictorial conventions through mechanical drawing.[66] Duchamp's use of mechanical drawing, however, reflects his effort to move away from pictorial representation by appealing to a form of schematism that relies on both visual and discursive cues. As he explains to Francis Roberts: "My approach to the machine was completely ironic. I made only the hood. It was a symbolic way of explaining. What was really beneath the hood, how it really worked, did not interest me. I had my own system quite tight as a system, but not organized logically."[67] Duchamp's experiments with mechanical drawing and other forms of technical reproduction are not based on physical or scientific principles; instead, they represent a "symbolic way of explaining," one that privileges the logic of the machine, only to reveal its ironic underpinnings. Commenting on Duchamp's annotations on the painted Bride, Richard Hamilton observes that: "They are an after-the-fact determination of a possible physical nature and operation, justifying the fortuitous disposition of forms which would be abstract if they did not give a strong illusion of existence and if some alien causality could not be read into them."[68] Using straightforward descriptions that are as exact as those of a "patent engineer," Duchamp hints that the fortuitous visual appearance of the Bride may be the expression of some form of physical causality, a manifestation of hidden physical laws and operations.

The Large Glass thus embodies both Duchamp's appeal to technical means of production and the machine, only to discredit through this very fidelity the logic of science. But why challenge painting by introducing scientific and technical considerations, only to humor them in turn? The answer, as provided by Duchamp, is quite simple:

All painting beginning with Impressionism, is antiscientific, even Seurat. I was interested in introducing the precise and exact aspect of science, which hasn't often been done, or at least hadn't been talked about very much. It wasn't for the love of science that I did

this; on the contrary, it was rather in order to discredit it, mildly, lightly, unimportantly. But irony was present. (DMD, 39)