Part III

The Islamic Jihad

6. Muslim Youth

The development of an Islamic movement in a country depends on the mercy of God. When God wants to show mercy on a place, he orders the wind and clouds to gather and leads them to a specific point where he wants it to rain. There it rains, and immediately the land changes, and a movement is created in it. The soil breaks up, and life raises its head from that spot. The Holy Qur’an is like this, and the country and people of Afghanistan are like that fallow land.

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar made this statement in a speech to Afghan refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan, in the early 1980s. [1] As the leader (amir) of Hizb-i Islami Afghanistan (the Islamic Party of Afghanistan), one of the principal Islamic parties then fighting to overthrow the Marxist regime in Afghanistan, Hekmatyar was primarily concerned in his speech with condemning the leftist leadership in Kabul and its Soviet sponsors. However, the head of the most radical of the Afghan resistance parties also took time to inform his audience about the origins of his party as a student group at Kabul University in the late 1960s. This reminiscence of student days was not a digression or flight of fancy. To the contrary, Hekmatyar’s historical reflections had considerable significance in the context of Afghan national politics, for it was through history that Hizb-i Islami staked its right to rule Afghanistan. Thus, because the Muslim student organization could claim to have been the first group to have warned the nation of the dangers of Soviet communism, Hizb-i Islami could declare its preeminence among the various resistance parties in Pakistan and assert its leadership of the Islamic government that it hoped to establish in the homeland. And because so many of the group’s early leaders were arrested and martyred by the communists, Hizb-i Islami was able to justify its often controversial actions: its relentless control over party members, its summary execution of political opponents, its often ruthless attacks against rival resistance parties, and its sabotage of attempts at political compromise to end the interminable conflict in Afghanistan.

In Part Three, I am again concerned with history, specifically, the history of the Hizb-i Islami political party, and with how this organization, which began as a campus study group, was transformed into an authoritarian political party. Although Hizb-i Islami has faded in importance, it was the dominant Islamic political party in the period preceding and following the Soviet invasion, and more than any other group it was responsible for undermining independent regional efforts to overthrow the Marxist regime; it also created the organizational template adopted (more or less successfully) by other Afghan resistance parties, and it established the climate of distrust and division that has plagued the development of an Islamic governing structure in Afghanistan to this day. [2] Hizb-i Islami had an impact far beyond the number of its fronts, which were many, or the effectiveness of its military operations, which was considerable. Indeed, the party’s principal legacy was political not military, and it is my contention that, along with the Khalq party, which it resembled in many respects, Hizb-i Islami was responsible for prolonging the conflict by consistently destroying grounds for common cause within the resistance and within Afghan society more generally.

My interest here is not only how this particular party forged a dominant place for itself in the Afghan resistance during the early 1980s but also how the party deviated from more traditional forms of Islamic political practice, especially the clerical and mystical traditions that had been at the center of earlier antigovernment political movements, and how it helped to keep the various Islamic political factions disunited in the face of the Soviet invasion, thereby laying the groundwork for the eventual takeover by the Taliban militia. In keeping with the general pattern of this book, this first chapter of Part Three has both a biographical and a historical focus. My main concern here is with the development of a political party and ideology, and my principal strategy for dealing with that topic is to consider one man’s life in the context of the larger historical events shaping his personal career and the trajectory of the party during the last half of the twentieth century. The second chapter of Part Three examines the structural divisions within the Islamic political movement in the wake of the Marxist revolution and the role of Hizb-i Islami in exacerbating these divisions.

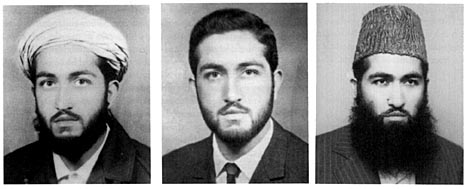

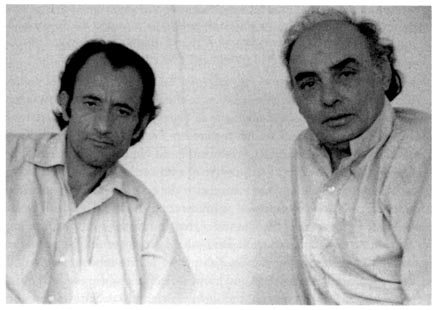

The life history at the center of this chapter belongs to a man known as Qazi Muhammad Amin Waqad, whom I met in Peshawar and interviewed once in 1984 and twice in 1986. “Qazi” means “judge” and is an honorific deriving from the fact that Muhammad Amin’s father was an Islamic judge and Muhammad Amin himself completed his studies in Islamic law and was qualified to serve as a judge. Muhammad Amin’s last name—“Waqad,” or “enlightener” in Arabic—is also significant, for it is a name he gave himself. Afghans traditionally do not have family names, but this lack began to create problems for those living in urban centers and mixing with large numbers of unfamiliar people, most of whom had similar names. Tribal Pakhtuns frequently dealt with this problem by using their tribe’s name as a family name, and the children of well-known fathers sometimes adopted their father’s name as a family name (for example, the sons of the Paktia tribal chief Babrak Khan became known by the name “Babrakzai”; sons of Mir Zaman Khan came to be known as “Zamani”). Others, however, among them many of the students who streamed into Kabul to attend the newly opened university in the 1960s and 1970s, made up their own last names (takhalus). Qazi Muhammad Amin was one of those students, and he chose a name that symbolically denoted the role he hoped to assume in the revolutionary political matrix that was emerging in his student years.

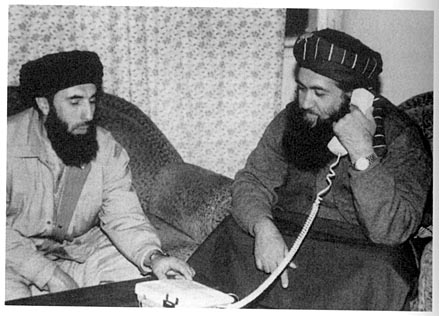

Although he served as the amir of Hizb-i Islami at various times during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Qazi Amin’s most familiar post was that of deputy amir (mawen), or number two man in the party. He held this position until resigning from the party in 1985 in protest over the acceptance of a Saudi-brokered political alignment that brought together the seven major political parties. Thereafter, he headed his own minor party but stayed mostly on the sidelines until a short-lived appointment as communications minister in the Islamic government that formed between the collapse of the Najibullah government in 1992 and the Taliban takeover in 1994. During the period of my interviews with Qazi Amin, the war inside Afghanistan was bogged down in what appeared to be a limitless stalemate; in Peshawar the resistance parties were engaged in their usual internecine disputes, and various outsiders—Pakistanis and Arabs in particular—were hovering around the edges of the action, trying to exert their authority. It was a time of corruption and of maneuvering for position—not a time of fervent conviction or inspired action.

Qazi Amin was very much in the middle of a scene that many people, outside observers and Afghans alike, were growing to loathe and resent. Ordinary mujahidin and civilians were getting killed, the refugees were sweltering in fetid camps, and—as far as I could discern—the party leaders were concerned primarily with their own interests and not with those of the people they supposedly represented. By the time I met Qazi Amin, I had already interviewed most of the party leaders and was convinced that the jihad would drag on endlessly and that the political situation would likely get more fragmented and corrupt before it got better. I was generally depressed with the whole situation and would not have been displeased had all the leaders been dispatched in a sudden accident.

Despite this attitude, I was able to muster some enthusiasm for meeting Qazi Amin, in part because I suspected that he might provide interesting links to historical figures like the Mulla of Hadda, whom I had already spent many months investigating (and whose story is told in Heroes of the Age). I had been informed that Qazi Amin was a Mohmand from eastern Afghanistan and that he was the son of a locally prominent judge who had also been a disciple of one of the Mulla of Hadda’s principal deputies. I also knew that, in keeping with family tradition and in contrast to most of the Muslim student militants who came to Islamic politics from secular schools, he had attended religious schools and had originally set out to follow the same conservative religious career path trod by his father.

The biographical facts that I had been told indicated that Qazi Amin’s life would provide a useful vehicle for looking at the transformations in Islamic political culture in recent years, but, given the general reticence I had encountered in other top leaders I had interviewed, I had no reason to think that this interview would prove any more enlightening. To my surprise, however, I found that Qazi Amin was quite welcoming in his attitude and sometimes even expansive in his answers. While I had a great deal of trouble getting detailed information from Hekmatyar and other radical leaders about their formative years, Qazi Amin allowed me to probe this area of his life and was not put off when I wandered into politically sensitive areas either. I didn’t always get satisfactory answers to my questions, but I never felt any hostility for having asked them.

At the same time, however, throughout the time I was interviewing Qazi Amin, it never left my mind that he was a top-level politician in a resistance organization whose mission was to destroy the government in the country next to the one in which I was then residing and whose political philosophy was equally antagonistic to the government of my own country (even if that government was at the time the party’s chief arms supplier). Kalashnikov-wielding guards were always present to remind me of Qazi Amin’s position, lest I forget, and the sometimes bemused but always wary cast of eye in his thickly bearded countenance continually reminded me of the status of the squat man sitting on the floor mat across from me.

Since Samiullah Safi and Qazi Amin are approximate contemporaries of one another (Safi being five years older than Qazi Amin, who was born in 1947), the life history in this chapter covers much the same historical period as that discussed in the two previous chapters. [3] Both stories also share a common regional focus in the Afghan-Pakistani frontier and certain prevailing themes, such as the transformation of older moral principles and organizational forms in the rapidly changing milieu of Afghan society. Despite these similarities, however, the two life histories share little else in either content or style. When I conducted my interviews with Samiullah Safi, he had been in exile for nearly two years, and he saw little chance of his returning to Pech. Consequently, our conversations had a somewhat elegiac quality to them, and I had the distinct impression that I was being used to record the completed story of another man’s life. My job, I perceived, was to get the story straight and to recognize in it the sense of moral coherence that the speaker intended to impart through his choice of words. During the course of the several hours of interviews—and I even hesitate to use the word “interviews” since it inaccurately represents the way he dominated our interaction and dictated the direction and flow of his reminiscences—I listened, nodded, and poured more tea.

The time I passed with Qazi Amin was invariably cordial, perhaps more so than that spent with Wakil, who was quite purposeful and at times even impersonal as he went about telling his story. But where I sometimes felt as though Wakil, despite his personally detached mode of presentation, was opening up chasms in his soul, my impression of Qazi Amin was that the more friendly he became in manner the more evasive he became in his answers. Thus, when Qazi Amin discussed his father’s life or his own early memories, his reminiscence flowed along without substantial prodding. However, when we began to drift into more contentious matters, such as the conflicts among the resistance parties, he often balked, providing a clipped reply and waiting for me to ask my next question. At the time of our interview, Qazi Amin was more engaged in the flow of political events. While Wakil was an exile from his home and the center of his own political gravity in Pech, Qazi Amin was right at the heart of the things in Peshawar, where the Islamic political parties carried out their business. What I didn’t realize completely then, however, was how at the time of our interviews Qazi Amin was also in decline. Like Wakil, Qazi Amin’s greatest influence was behind him; he would never again enjoy the degree of power and authority he wielded in the early part of the jihad. Like Wakil as well, Qazi Amin declined in importance largely because he was a hybrid—neither fully one thing nor the other. In his case, hybridity had to do with his having one foot in the world of the traditional cleric and the other in the world of radical student politics. Initially, being able to negotiate and maneuver in both these worlds was his strength and great contribution to the jihad, but when the fissures in the jihad proved too deep to cross he became peripheral to the interests of men more single-minded and ruthless than himself.

To reflect the differences that I sensed in the two interviews, I have chosen to represent them in somewhat different ways. Since Wakil’s interview consisted of a series of stories, I fashioned them that way, excising extraneous comments by others who might have been in the room (including myself) and, in some cases, taking out the noise, clutter, and repetitious filler that occasionally obscured the narrative contours of Wakil’s material. For Qazi Amin, however, I have retained the interview framework within which the life history emerged because it was always within this context that our conversations proceeded, and the question-and-answer format was never left behind.

My primary concern in this chapter is with the evolution of the Hizb-i Islami party, but before turning to that subject I provide accounts of Qazi Amin’s father’s career, the transformation of Islamic politics in the first half of the twentieth century, and Qazi Amin’s own early education. These sections of personal and political history help to contextualize developments while also providing a link between the earlier forms of religious dissent and those that were to emerge in the democratic period. Following these introductory sections, I use Qazi Amin’s personal history to examine the development of Hizb-i Islami up through the Marxist revolution. As a way of organizing this discussion, I divide this history into two principal stages: an initial period of campus-focused activism and peer engagement lasting roughly from 1966 until the official founding of the Muslim Youth Organization in 1969 and a second period of increasing radicalization between 1969 and 1978, during which time the Muslim Youth launched an abortive coup d’état against the government; the failure of this coup almost destroyed the party, but it also set the stage for Hizb-i Islami’s emergence as the most radical, secretive, and controlling of the Islamic resistance parties.

Early Histories

Interviewer (I):Would you please provide us with some information about your father, other family members, and your background?

Qazi Amin (QA):My name is Muhammad Amin. My father’s name is Muhammad Yusuf, and my grandfather’s name is Maulavi Sayyid Muhammad. We are from Ningrahar Province in Afghanistan. In Ningrahar Province, our home is Batikot, and we belong to the Mohmand tribe. Within the Mohmand tribe, we belong to the Janikhel branch. My grandfather served as the prayer leader [imam] of the village and taught Islamic subjects in the mosque school. I never saw him. My father was only about fifteen or sixteen years old when his father died. . . .

My grandmother belonged to a sayyid family [those who claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad] that lived in a place near Inzari of Shinwar. They were very wise people, and my grandmother was also very wise and able and knew how to educate her sons; so she sent all four of her sons, including my father, to India to educate them in religious studies. After being in India for some time, the older brothers sent their younger brother, Amir Muhammad, back home to serve their mother while they stayed on [in India]. One of the brothers died during this time, and the other brother returned home without finishing his education. But my father, Muhammad Yusuf, spent twelve years in India and completed his education . . . at the Deoband madrasa, which was the greatest center of religious sciences at that time. Everyone who could finish his education wanted to go there. . . . He spent two years in Deoband and graduated first in his class.

My father returned from Deoband in 1937 or 1938. . . . At that time, there was a custom in Afghanistan that the religious scholars who had graduated from Deoband or from any other madrasa in India would be appointed as judges by the government. In 1938, Mia Sahib of Kailaghu asked my father to accept a position as a judge. Mia Sahib was a judge and a very high-ranking religious scholar in the Afghan government of the time, so my father accepted the offer. First, he went to Gardez and later to Khost. Then he moved to Katawaz, and for some time he was in Ghazni. In the beginning, he was a lower-court judge and later became a provincial judge.

My father was a very accomplished scholar and had an attractive appearance, and when part of his body became paralyzed, people said to each other that it was because of the evil eye. He also had the power of eloquence in his speaking, and he knew a great deal about the political and social affairs of his time, especially the different tribal traditions. Because of this, when the government accepted him as a judge, they sent him to Paktia, which is a border province of Pakhtuns, and he was able to work successfully there—first as a lower-court judge and later as a provincial judge. He was a judge for a total of six years. In 1945, the sixth year of my father’s employment, I was born in Khost [Paktia Province]. So I am now forty years old. At that time, the Safis had started their war against the government in Kunar Province.

(I):What did your father do after he got sick?

(QA):After his sickness, my father spent the rest of his life in Kot. Even though the government asked him many times to go back to his job, he wouldn’t agree. We lived on the income of our land. We had oxen for plowing and also a tenant farmer to work on our land. Besides that, our father was the preacher in the main mosque, and he also had some students. But unlike other mullas, he didn’t accept any assistance from the people, and because of this, the people of the area called him “khan mulla,” the mulla who is like a khan. Our father was a mulla who had his own guesthouse and fed every kind of visitor there. We didn’t need anyone’s help. Our father always tried to help the people in our area settle their disputes, so our living standard was equal to a khan’s living standard. We had land, we had a guesthouse, and we could solve the problems of the people.

(I):Did your father have any kind of relation with pirs or Sufis like Enzari Mulla Sahib?

(QA):My father was a disciple of Pachir Mulla Sahib, who lived in Pachir, which is near Agam. I have seen him myself. He was alive until recently. His sons were martyred in the jihad: Maulavi Abdul Baqi and his other son. Pachir Mulla Sahib was a disciple of the Mulla of Hadda, and my father was a disciple of Pachir Mulla Sahib, who was a very prayerful and pious man. [Pachir Mulla] liked to lead the life of a simple man of God [faqir].

(I):You said before that your father was both a good preacher and was popular with the tribes. Did the government send him to work in the tribal areas because he was better able to control the tribes than a secular person would have been?

(QA):Yes, that was the way the government kept control of the tribes. In those days, the people were uneducated, and the military bases weren’t very strong, so the only way the government could keep its control over the people was by using religious scholars and popular tribal leaders. Military force was not enough. For example, the people of Paktia were uneducated, and the military bases were not strong enough to control the tribes. The government at that time was newly formed and still quite weak. Consequently, they had to depend on religious scholars and popular tribal leaders to maintain their authority over the people. On the one hand, religious scholars had spiritual influence and power, and as good orators and preachers of Islam they could easily find an esteemed position among the people. On the other hand, they had government authority, too. [4]

Qazi Amin’s description of his father’s life reveals some traditional patterns in Afghan religion. Following time-honored precedents, Muhammad Yusuf, while a young man, journeyed far afield for scriptural knowledge before returning to his homeland to assume the mantle of a respected cleric in the government. Like the young Najmuddin Akhundzada, who later became known as the Mulla of Hadda, Muhammad Yusuf had a religious background. He was, in fact, more favored in this regard than Najmuddin, for not only were his father and grandfather religious scholars, but his mother had also inherited sanctity as the result of being a member of a family claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad. Muhammad Yusuf, however, also had the same disadvantage as Najmuddin—of being left fatherless at a young age—and like Najmuddin and many other boys in similar circumstances, he responded by going in search of religious knowledge and the credentials that would allow him to establish his own identity and social position as a scholar.

All of this is familiar, and so is the fact that on completing his education Muhammad Yusuf returned to his home area to marry and begin employment in a local mosque as a prayer leader and teacher. This was not the route that Najmuddin took, but few had the inner disposition to lead the life of a mystic and ascetic who could forego family, wealth, and position to single-mindedly serve God. While he had mystical leanings of his own and became a disciple of a well-known pir, Muhammad Yusuf’s orientation was primarily scholarly, and his decision to return to his home to start his own madrasa reflects this fact. Traditionally, Afghan men of religion have combined elements of both the mystical and the scriptural in their lives. While in some settings Sufism and scripturalism tend to attract different sorts of adherents, who keep their distance from one another, most well-known Afghan mystics (including the Mulla of Hadda) have been respected scholars, and likewise most respected scholars have been themselves Sufi pirs or disciples of Sufi pirs. The decision whether to be primarily a mystic or a scholar is an individual one, but clear social incentives and disincentives come into play in each situation. In the case of Najmuddin, apparently very little pulled him back to his home area. He was from a poor family, and he would likely have ended his days as a poor village mulla if he had returned home. Muhammad Yusuf, however, was from a relatively prosperous family, which meant that, on his return from India, he had land and income waiting for him, along with the prospect of a socially beneficial marriage.

Another pattern that we see in the father’s life history that is less familiar, at least if we take the Mulla of Hadda and his disciples as our point of reference, is the scholar accepting employment with the government. As I discussed in depth in Heroes of the Age, the reputation of the Mulla and his closest followers stemmed in large part from their separation from and periodic opposition to the government, but such opposition became increasingly rare through the early part of the twentieth century as the government expanded and offered an ever larger number of religious scholars employment in its service. [5] In this sense then, Qazi Amin’s father’s life exemplifies the increasingly common trend toward the routinization and bureaucratization of religious authority—and the increasing irrelevance of religion as a force of political dissent through the first half of the twentieth century.

The pattern of increasing cooperation between religious leaders and the states can be seen quite clearly by considering the case of the Mulla of Hadda’s tariqat (Sufi order). Following the death of Amir Abdur Rahman in 1901, his successor, Amir Habibullah, persuaded the Mulla to return to Afghanistan and treated him with great respect and tolerance. [6] The Mulla had been a vociferous opponent of Habibullah’s father, who had tried to arrest him. The Mulla escaped, but several of his disciples had not been so fortunate. Habibullah wanted to mend this break, and signaled this attitude in a number of ways, one of which was the exemption of religious leaders from paying taxes and, in some cases, the assignment to them of tax revenues. Because of the Mulla of Hadda’s standing as the most renowned religious figure of his day, Amir Habibullah gave him valuable land in the fertile valley of Paghman, a few kilometers outside of Kabul, and later issued a decree that the government’s tax receipts from the area around Hadda, which amounted to 3,500 rupees in cash and thirty-two kharwar of wheat, be given to the Mulla for the support of the langar where he fed his disciples and guests. [7] The state also allocated annual stipends to his principal deputies, including Sufi Sahib of Batikot, who received 2,500 “silver rupees,” and Pacha Sahib of Islampur, whose allowance included 1,400 silver rupees and twenty-one kharwar each of wheat and straw to support and maintain his langar and mosque. [8] While many religious figures appreciated this more favorable treatment, a number, including the Mulla of Hadda himself, recognized the potential danger entailed in accepting government largesse. Hadda Sahib even went so far as to return to the amir the land he had received, saying that it was the property of the people (bait ul-mal) and therefore forbidden to him.

Though Amir Habibullah’s efforts at placating traditional religious leaders appear at odds with his father’s style of rule, the same impulse toward consolidating monarchical authority was at its root. Where Abdur Rahman had recognized the necessity of strengthening the power of the center at the expense of religious and tribal leaders, Habibullah apparently believed that the balance of power had now shifted in the government’s favor and that the moment was auspicious for taking a more conciliatory approach focused on symbolic inclusion of dissident elements rather than forcible removal. [9] Whatever his motivation, one effect of his largesse to religious leaders was the decline of their popular authority. Acceptance of government funds for the upkeep of a langar was tolerable in most people’s minds, but the perception became increasingly widespread that some of the mullas’ deputies and their offspring were on the government dole and were more devoted to property than piety. [10] Given the unstable nature of charismatic authority, it is probably the case that the Mulla of Hadda’s tariqat would have declined with or without Habibullah’s assistance, but government interference certainly accelerated the process, as did the government’s practice of implicating religious leaders in local administration.

This policy was played out during the Anglo-Afghan War in 1919. In the decade and a half between the Mulla of Hadda’s death in 1903 and the outbreak of hostilities with Great Britain, various of the Mulla’s deputies, including Mulla Sahib of Chaknawar and Sufi Sahib of Batikot, had appeared from time to time among the border tribes to try to provoke an uprising against the British government in India. None of these efforts had created the sort of widespread disturbance that the Mulla of Hadda had helped to instigate in 1897, but the labors of the mullas were sufficient to keep the frontier in a state of nervous alarm for much of this period. [11] They also succeeded in keeping alive their own reputations as men of political action, but this was to change when their independent efforts were harnessed to the government’s cause in 1919.

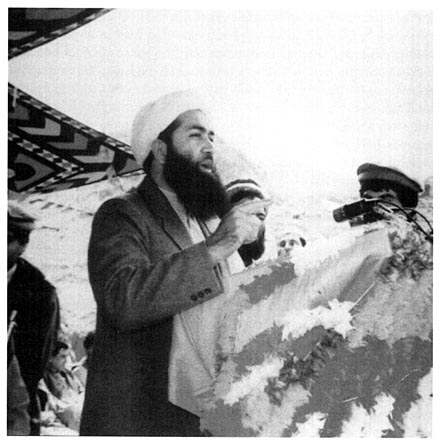

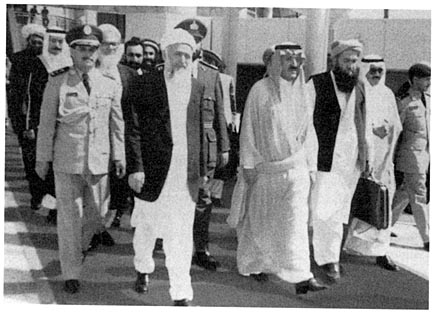

Upon declaring jihad against the British, Amir Amanullah, Habibullah’s son and successor, immediately sought the assistance of religious leaders, including the Mulla’s deputies. By this time, many of those personally associated with the Mulla were getting on in years, but those who were still in a position to participate in this new jihad did so. [12] This time, however, they were not treated as independent leaders but rather were incorporated into the command structure as subordinates of Amanullah’s own representative, Haji Abdur Razaq Khan, who recognized the value of these spiritual figures for organizing the tribes. Religious leaders were a key ingredient in Abdur Razaq’s plan because of their ability to move across sometimes hostile tribal boundaries and coordinate activities among groups that might otherwise have only ill-will for one another. Razaq also understood that spiritual leaders had both the education and the trust needed to oversee the movement of weapons, ammunitions, and supplies to different locations and to keep rival tribes focused on the enemy rather than on each other. [13] The religious leaders went along with this plan because of their longstanding interest in combating British influence on the frontier, but their cooperation came at a cost. The Mulla of Hadda had been careful never to accept a subordinate position to the Afghan amir and in fact had contested the amir’s right to declare a jihad on the grounds that he was not a proper Islamic ruler. In the 1919 war with Great Britain, however, the Mulla’s deputies, who succeeded him after his death, not only conceded the right of announcing jihad to the state but also ceded their position as independent leaders of their tribal followers for the more circumscribed role of logistical coordinators charged with supervising operations at a middle rung in the chain of command.

While the organizational arrangements established during the 1919 war demonstrate the changing relationship of religious leaders to the state, the best illustration of the government’s harnessing of religious leaders to its own ends came in the ceremony that the government held following the conclusion of hostilities to commemorate Afghanistan’s “victory” over Great Britain. [14] The site of the ceremony was a field next to the Mulla of Hadda’s tomb. When the delegates to the assembly had all gathered, General Nadir Khan (later King Nadir Shah), who was Amir Amanullah’s representative, called on the members of the assembly to prove their readiness to renew the jihad against the British by signing their names on the inside cover of a Qur’an. As each leader signed his name, he was also asked to indicate the number of mujahidin he would provide and the area where he would fight. Nadir then presented them with engraved pistols and battle standards inscribed with Qur’anic verses. Playing the symbolic dimensions of the occasion to maximum effect, the government had decorated the meeting ground with black banners (a time-honored emblem of Islamic militancy) that had been consecrated at the shrine of Hazrat ‘Ali in Mazar-i Sharif, the principal shrine and pilgrimage site in Afghanistan. These banners were embroidered with religious motifs, such as the outline of a hand (symbolic of the five principal members of the Prophet’s house), the star and crescent, and the silhouette of a mosque.

The deployment of these symbols for the state’s purposes demonstrates the way in which Afghanistan was moving from a nineteenth-century kingdom to a twentieth-century nation-state. The symbols that we see arrayed on this occasion were traditional ones that governments in the past had also found it in their interest to use. So, to a certain extent, nothing new is going on here. However, if seen in relation to more general patterns of government centralization and administrative rationalization, the political performance at Hadda, with its skillful management of tribal and religious leaders, can also be recognized as one part of an overall consolidation of political authority in the hands of the government. In 1920, when the assembly at Hadda occurred, this consolidation was by no means complete, and in the years to follow religious and tribal leaders would make renewed assertions of independence, but the overall direction was toward increased government control and a more institutionalized role for traditional religious leaders. [15]

The general trend toward compartmentalizing religious leaders in the apparatus of state rule would appear to have suffered a major setback with the overthrow of Amanullah, which is generally thought of as a victory for conservative Islamic leaders over the social reformers who wanted to modernize Afghanistan and the high-water mark of religious influence in the affairs of state. [16] The legacy of that event is more ambiguous and complex than it might appear however. One of the interesting features of the movement that succeeded in toppling Amanullah is that its principal religious leader, the Hazrat of Shor Bazaar, had his base not in the tribal areas (as was the case with the Mulla of Hadda and his deputies), but in Kabul itself. It is true that most of the Hazrat’s disciples were Pakhtun tribesmen living in the tribal areas, but he himself chose as his base of operations the capital city. In the past, religious leaders tended to have regional power bases, but the Hazrats found that they could sustain a multiregional constituency from Kabul. This reflects the changing articulation of religious authority, as more and more of the Hazrat’s disciples were doing business in Kabul, and it became easier to stay in contact with his scattered deputies from the capital than from a rural location. The Hazrat gave up the security of having tribesmen close at hand and mountains nearby to flee to in case of government attack; however, he discovered that his larger base of disciples gave him protection, even in Kabul, since the government feared the agitation that would result if it tried to arrest a leader of his stature. At the same time, having established himself in the capital, the Hazrat was loath to see the dismantling of the state, even if he had been more than willing to help unseat the head of state. Thus, even though the overthrow of Amanullah unquestionably represents the moment when the expanding authority of the Afghan state received its most crushing setback (at least until the upheaval of the 1980s), the two consequences that stand out after the sound and fury of the uprising itself are put aside are how quickly the central government reasserted its authority in a form much like that which had preceded it and how quickly religious leaders like the Hazrat of Shor Bazaar acquiesced to this development and accepted an administrative niche within the structure of state rule. Kabul may have been overrun and the various palaces and offices of the government ransacked and looted, but those who had attacked the city quickly returned to their places of origin and resumed their former lives. Government bureaucrats reoccupied their offices. The army was put back together. Students took their seats in class as they had before, tax collectors returned to their rounds, and the fiery Hazrat of Shor Bazaar accepted a post in the new government, becoming the head of a council of clerics (jamiat ul-ulama), which was appointed to advise the government on religious policy.

In fact, neither the Hazrat nor the council ever wielded as much influence as they seemed prepared to do at the beginning of Nadir’s reign, when he reportedly availed himself of their counsel and accepted their authority in certain areas such as judicial sentencing and the oversight of government legislation. Likewise, in testament to the preeminence of the Hazrat, Nadir not only contracted marriage relations with his family but also gave the family a large tract of land for a new compound on the outskirts of Kabul. These privileges and perquisites, however, did not provide the ulama with the authority that they sought. Indeed, bringing them into the councils of power and even into the royal family itself seems to have gradually reduced their authority by diluting the importance of their relations with the people in the rural areas. Ultimately, once the throne was secure and the tribal areas were pacified, the king and his ministers gradually began to pay less attention to the advice and dictates of the council of clerics. While the state continued to pay stipends, build madrasas, hire judges, and otherwise ingratiate itself with religious leaders in material ways, it also came to pay less heed to their admonitions on social and legislative matters.

Since the government was not embarking on any radical reform programs that might have stirred the ire of religious leaders, they had little to protest; most clerics simply accepted the largesse offered them without complaint. The government’s generosity was of the calculated variety, however, and its principal objective appears to have been to forestall the religious establishment from uniting against the government in the future. While it was impossible for the government to prevent the appearance of charismatic malcontents like the Mulla of Hadda, it could limit their effectiveness by maintaining a stable of compliant clerics who could be called on to denounce outsiders’ charges and complaints. This strategy was in fact recognized by the very group that was implicated in the government’s web of generosity, as is indicated by the following statement made to me by the descendant of one of the Mulla of Hadda’s deputies who had served for many years as a judge in the Afghan court system:

[Prime Minister] Hashim Khan [1933–1946] encouraged the children of pirs to move toward the government. He wanted to enroll them in madrasas to turn them away from Sufi orders [tariqat]. Hashim also offered them good government positions and did his best to provide them with everything possible. In this way, he also strengthened his own position and power. He could claim that that pir or his sons are working for us or they are our subordinates and we pay them. In this way, Hashim gradually broke the people’s link [to the pirs]. [17]

Returning to the case of Qazi Amin’s father, we can see that while he was situated far lower on the ladder of prestige than the Hazrat of Shor Bazaar or the children of the Mulla of Hadda’s deputies, he too was affected by the changing balance of power. Like these more exalted luminaries, he was consumed with affairs of government, and when a tribal uprising appeared on the horizon, he and his fellow scholars naturally tended to take the government’s side and protect its interests. Thus, according to Qazi Amin’s recollection, his father helped to mediate three tribal uprisings—one among the Zadran tribe in Paktia Province, the Safi uprising in 1945 (about which Qazi Amin had little information), and an uprising among the Shinwari, which he believed occurred in the late 1930s or early 1940s. [18] The one traditionally independent political role that Qazi Amin’s father did perpetuate was in connection with the practice of amr bil ma‘ruf (calling people to proper faith and action), a role that the Mulla of Hadda and many of his deputies also performed. In this tradition, groups of religious leaders traveled from village to village, urging people to renew and purify their faith. Sometimes they also tried to convince the people to abandon customary practices, such as taking interest on loans and money in exchange for giving their daughters or sisters in marriage. The continuation of this form of proselytizing at a time when other political activities were discontinued would seem to reflect an interiorization of religious politics—a movement toward local social reform as opposed to the more dangerous and uncertain area of antigovernment dissent.

The Making of a Muslim Radical, 1959–1964

(I):Tell me about your early education and how you got interested in Islam as a career.

(QA):We are two brothers. My elder brother is Muhammad Yunus. He is eight years older than I. After my elder brother, my sister was born, and I was the last one. . . . Our life was a typical rural life. It was an ordinary village life. We were away from the city. My elder brother started his primary education under his father’s supervision, and he also attended the madrasas that were located close to our area. When I reached school age, I also started to study some elementary books of Islam. . . .

I was fifteen years old at that time. I didn’t attend any official madrasa, and I thought that I couldn’t finish my education at home. So, without my father’s permission, I came to Pakistan. I was sixteen years old, and I made up a story that I wanted to visit my uncle’s family in Kama. First, I went to Kama, and from there two other boys and four sons of my uncle joined me, and we all came together to Pakistan through Gandhab. Here, we stayed in an official [government] madrasa [rasmi madrasa]. My family found out where I was after six months of searching, and my brother came after me. He asked me, “Why did you come here?” I replied, “You know that there isn’t any suitable place for higher education in our area, and I have the right to continue my studies. I knew that father wouldn’t let me go to Pakistan, so I came without his permission.”

I had spent nine months in the madrasa. Then I went home and tried to convince my father to let me stay. I told him that I had gone to get my education, and eventually he allowed me to go to Pakistan for a second time. Again, I spent nine months here, this time at the madrasa in the Mahabat Khan mosque in Peshawar, where I studied some advanced books and learned calligraphy. At that time in the madrasa, they didn’t pay much attention to calligraphy. After that, the idea came to my mind that it would be difficult to continue my education in this foreign country. There was another problem also that if someone had graduated from [a school or madrasa in] Pakistan they would be criticized by the government. When I was a student [taleb] in the Mahabat Khan madrasa, the idea came into my mind that I had to go back to Afghanistan and register myself in one of the official madrasas of the government.

So in 1340, which is equivalent to 1961, I returned to Afghanistan after being in Pakistan for eighteen months. Then I applied to madrasa and took an examination. After successfully passing the examination, I went with my father and registered in the fifth class of Najm ul-Madares of Hadda. Although the usual period of study was seven years, I finished the program in six years. Since I was good at my lessons, I prepared myself for the examination of the eleventh class during vacation, and I passed and registered in the twelfth class.

(I):What were the rules for admission to the madrasa?

(QA):Generally, they admitted just those who had finished in the first, second, or third positions in their classes, and they also had to pass the examination. Recently, they have been accepting talebs from local mosques as well.

(I):Can you describe the program of study? Did you just attend classes in the morning, or did you have them in the afternoon as well?

(QA):Our lessons were conducted from eight in the morning until twelve noon. Since this was a religious school, the majority of the subjects were of a religious nature, but there were some other, nonreligious subjects like Pakhtu, Farsi, and Arabic. In the preliminary program up to class six, there were also mathematics, geography, geometry, and history. In the last year before my graduation, they added English to the preliminary program as well. There was also a little bit of modern science in the advanced program—courses like mathematics, geography, and social science—but the main subjects were religious.

(I):Did you take any interest in Sufism [tasawuf] at that time, and did you ever become the follower of a pir?

(QA):No, I didn’t pledge obedience [bayat] to any pir.

(I):Was this because you didn’t believe in it, or were there some other reasons?

(QA):I didn’t have faith in what they were doing then. The other side of Sufism is its spiritual side—doing zikr for Allah. [19] I believe in this side. It has a positive effect on people’s morale. I have some books about it. One of them gives directions for [making] amulets [tawiz] and [doing] zikr. I study [this book], but what the pirs are doing nowadays is simply deceiving people to get money, and this is condemned by Islam. They are using religion as a way of getting material benefits and power, which is a very bad use of religion. Because of this, I haven’t taken an interest in that kind of master/disciple [piri-muridi] relationship.

(I):What did you do when you graduated from madrasa?

(QA):It was a rule of the government at that time that they would employ some of the graduates as madrasa teachers and they would choose others to be judges. It seemed like a crime to the majority of people if someone wanted to go to university after graduating from madrasa. The people considered it frivolous and maybe even deviant. Despite this, I thought that my education was insufficient. I had to study more, and for that reason I asked my father about going on for more education. He asked me what kind of position the government wanted to give me after graduation from the madrasa. I replied that I could be a teacher now or a judge after attending a special one-year judicial course. He told me that being a judge was an important job: “It is my advice to you that you don’t need more education. You can attend the judicial course, and later you will be a judge, and it is enough for you.”

I didn’t accept his advice, however, and convinced him that I had to complete my education. I was the only graduate of the Hadda madrasa at that time who registered his name for the university examination. A total of twenty-four students graduated from the Hadda madrasa, and I was number two in my class. All my classmates rebuked me. Even our teachers criticized my action, especially Maulavi Fazl Hadi. He asked me, “Why are you going to go to the university? That is like a Western society there, and the people are decadent. So how can you—the graduate of a madrasa—go to such a place?”

(I):Why did you decide to go to university when no one else supported this decision?

(QA):I registered in the madrasa in 1961. Democracy came to Afghanistan in 1963, when Daud was deposed [as prime minister]. Afterward some of the political parties started their activities. For example, Khalq and Parcham began their work in 1964. The Afghan Millet party also began its activities at that time. So after democracy came to Afghanistan, we could get some information about political ideas, but the political awareness of our teachers was very low. I myself was not very aware when I was in madrasa, but, in spite of this lack of awareness, I and Maulavi Habib-ur Rahman [later a founding member of the Muslim Youth Organization], who was three years ahead of me, and some other close friends had a feeling of hatred toward the deviations and unjust activities of the government. . . .

There was a rule in the madrasa then that the students who had reached the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth classes had to preach twice a week in front of a big gathering. Our preaching was different from the others. Sometimes we discussed the current political problems that the other mullas never talked about. We had some teachers in the madrasa who were against that sort of political awareness. There were some other people who didn’t know anything about political ideas and were unaware of that kind of political thinking or feeling. For instance, they didn’t know what jihad is, what politics or the movement is, and what the significance of the leftist parties is, what democracy is. We were in a very backward environment, and since I had a feeling about these things, I decided to go to Kabul University for my higher education. So it was in the university environment that I became aware in a good way about the problems of my country. [20]

Qazi Amin’s story begins much like his father’s (and that of so many other scholars before him) with the mandatory pilgrimage in search of knowledge. In his case, the act of undertaking this pilgrimage also entailed an act of disobedience since he did not have his father’s permission to make the trip to Pakistan. That such permission was not forthcoming is not surprising considering both the boy’s tender age and his father’s established position in society. Qazi Amin was not an orphan seeking social advancement as his father had been, and there were better career options close to home than there had been when Qazi Amin’s father was a young man. At any rate, Qazi Amin’s decision to leave his home shows early on his independent character, just as the later decision to return home shows his pragmatic bent.

At the time of his journey (roughly 1959–1961), Afghanistan and Pakistan were embroiled in a bitter dispute over the control of the tribal territories along the frontier. The status of the frontier tribes was an ancient source of acrimony, but the tensions had escalated further when Muhammad Daud became prime minister in 1953. As a result of this dispute, there had been occasional clashes between army units of the two nations, sporadic border closings, and much vituperative rhetoric flowing out of both Kabul and Rawalpindi. While it was still as easy as ever for local people to cross the border, it was not always expedient to do so, and Qazi Amin wisely decided to return home so as not to jeopardize his chances for either further schooling or future employment in Afghanistan. The fact that a young religious scholar from the border area would have government employment on his mind is one indication of the extent to which the balance of power had shifted in favor of the state.

In a few short years, Qazi Amin’s life would take an unpredictable turn that would make considerations of employment irrelevant; but in 1961 he was preparing for a career as an Islamic judge, and that meant applying for entrance into one of the government madrasas, whose graduates were being awarded an ever larger percentage of the judgeships in the country as well as the most sought-after teaching posts in government secondary schools. All of this seems unremarkable, unless we compare the course of Qazi Amin’s early education with that of an older scholar, like his father or, better yet, the Mulla of Hadda. Such a comparison makes clear the degree to which education was becoming both routinized and centralized. In the past, students had had to go far afield to gain the requisite training, but increasingly that was neither necessary nor, from a career standpoint, desirable. The government had always looked to religious scholars to meet many of its administrative needs, but from the time of Abdur Rahman on, and particularly in the middle decades of the twentieth century, it strove to exert control over the process by which religious scholars were produced.

As revealing as Qazi Amin’s choice of career trajectories is for understanding the changing nature of relations between the state and Islam, an even more telling index of the government’s control over religious affairs is the fact that he received his preliminary training for later government employment in a madrasa built next to the Mulla of Hadda’s center. At the turn of the century, this very same center, whose grounds the government was now grooming, had been one of its primary sources of worry and irritation. In the Mulla’s day, the center at Hadda had been a pilgrimage site for disciples and scholars. Following the Mulla’s death, however, Hadda began a slow decline into ramshackle senescence. Given the renown achieved by the Mulla, it might have been expected that the center to which he had devoted a good portion of his life would have become a place of pilgrimage after his death, but Hadda, for reasons that are difficult to assess, failed to flourish as a shrine center. [21] During the 1930s and 1940s, the government, prompted by religious scholars, embarked on a program of underwriting the construction of madrasas in various regions of the country. In all, ten government-sponsored madrasas were established, and the graduates of these institutions went on to become judges, administrators in the Ministry of Justice, and high school teachers in the secular educational institutions that the government was then constructing with even greater avidity. [22] The madrasa at Hadda was not only established on the site of the Mulla’s center but was also named after him (the najm in Najm ul-Madares comes from the Mulla’s birth name, Najmuddin) and used his collection of books as the core of its library.

Although the Mulla was long dead by the time Qazi Amin arrived in 1961, the Mulla’s spirit, it seems, was all around and was often invoked. Yet one wonders what he would have thought of the government taking so prominent a role in the maintenance of his legacy. On the one hand, it was precisely the sort of development he had always advocated. The state needed to be guided by religious precepts, and what better way to ensure that it was than by providing religious adepts in each generation with education and employment. On the other hand, religious leaders had the responsibility to ensure that the government was not corrupt, and it was not always easiest or most reliable to seek such assurances from within, particularly in the absence of men on the outside decrying lost virtues and rallying the opposition. One can imagine that Hadda Sahib would have had good reason to worry, and the reason can be seen in the career choices of the offspring of his own deputies, the majority of whom pursued the path of Islam on the government payroll.

However, Qazi Amin’s generation was to prove different, for while its members were afforded the opportunities of a government-sponsored education, some were skeptical of the government’s good will and were inclined to challenge authority generally. As Qazi Amin’s testimony indicates, most of his classmates were not radically disposed. They viewed their education as the necessary means to the end of a decent government sinecure, and they were not inclined to talk back to those who were offering this largesse. But some, and Qazi Amin was among this number, were more aware of the political currents then beginning to circulate in the country and more cognizant of the limits of their own education.

In contrast to the situation at the time of Hadda Sahib, or even later during the movement against Amanullah, government opposition was no longer centered in the hinterlands but rather was focused in Kabul, within the narrow universe of the educated elite. During Qazi Amin’s youth, in the 1950s and early 1960s, the most vociferous opposition came not from the conservative side of the political spectrum but from the left. Several newspapers published briefly in the early 1950s advocated social reforms of a type that had not been espoused since Amanullah’s rule. [23] The most vocal of these publications demonstrated a willingness to attack not only the religious establishment but also popular religious practices, which many adherents of secular reform were ready to brand as superstitious and inimical to progressive ideals. This provocative attitude was dramatically demonstrated in a letter to the editor in which the government was criticized for spending money to refurbish the so-called mou-i mobarak (miraculous hair) shrine in eastern Afghanistan, which housed what was purported to be one of the beard hairs of the Prophet Muhammad. Clerical outrage over this letter led to public protests against the growing influence of secular reformers in Afghan public life, and the government responded in 1952 by banning Watan and other independent newspapers that were giving voice to these inflammatory challenges to traditional beliefs and practices. [24]

By the time Qazi Amin was finishing his education at the Hadda madrasa in 1968, leftist provocations were being revived through the efforts of leaders like Nur Muhammad Taraki and Babrak Karmal, both of whom had cut their political teeth working for progressive newspapers in the early 1950s. By and large, those living in the rural districts of the country were only dimly aware of leftist activities in Kabul, but news of a few episodes, like the mou-i mobarak incident, did reach the countryside and created a general though unfocused sense of alarm. Qazi Amin did not mention any incidents specifically, but he and his madrasa classmates were aware of the reputation of leftists in Kabul. They were equally aware that established Muslim leaders had proven ineffective in responding to these events, and in his own immediate context he could see the reluctance with which the ulama involved themselves in political matters. Older religious leaders had risen up to meet the challenges of colonial rule in India and of corruption and abuse in Kabul, but the current generation of religious leaders seemed more interested in maintaining their positions and their paychecks than in embracing their political responsibilities. Equally distressing, they appeared hardly to recognize the nature and extent of the challenge represented by leftist forces in Kabul, a challenge that would demand forms of redress unlike any that Muslims in Afghanistan had ever resorted to in the past.

While it is impossible to judge how politically aware Qazi Amin was during his madrasa days, it is interesting that he represented his resolve to meet the challenge presented to him as an act of defiance against his teachers and his father. Two paths were available to him. The first was the one for which he had been training all his life—the path of an Islamic judge, the path his father took before him and that he himself set out on when he followed his father’s example of seeking religious education in the subcontinent. This path was the one expected of him and the one that the majority of his contemporaries chose, but he rejected it in favor of the second path, enrollment in the university. Like Samiullah Safi, who felt the pull of the city and the allure of participation in the emerging political debate over national development, Qazi Amin recalled this turning point in his life in relation to the national political debate of the time, and he too framed his decision to join that debate as an act of disobedience, which links him not only to his contemporary, Samiullah Safi, but also to Taraki, to Samiullah’s father, Sultan Muhammad Khan, and to the Mulla of Hadda, all of whom likewise had to break from their fathers and the traditions of the past in order to become what they imagined themselves to be.

The Birth of the Muslim Youth Organization, 1966–1969

(I):What was the atmosphere like when you arrived at the university?

(QA):Our four years of university were the most important years of political involvement because democracy had just come into being and the parties were just starting their activities. The parties that were actively working at that time were Khalq, Parcham, Shula-yi Jawed, Afghan Millet, and Masawat; but among all of these the communists were the most active, especially in 1968, when I registered in the university. It was the time of political clashes and conflicts at the university. On that account, among some Muslim youth at the university the idea occurred to form a movement according to Islamic rules. I joined this movement in its first stages.

(I):Where were most of the students who attended the Faculty of Islamic Law [shariat] from and what kind of conditions did you find there?

(QA):I graduated from madrasa in 1968 and entered the School of Islamic Law at Kabul University in 1969. There was only one university in Afghanistan, and the students were from all parts of the country. Since the Faculty of Islamic Law admitted only graduates from religious schools, most of the students at the faculty came from Abu Hanifa Madrasa [in Kabul] and from [madrasas in] the northern parts of Afghanistan. There were only two students in the school from the Hadda madrasa, and there were very few students in general from other border-area madrasas. About 60 percent of the Islamic law students did speak Pakhtu however.

(I):What were conditions like in the university dormitory?

(QA):Kabul University had one dormitory, which could accommodate twenty-five hundred students. We were all living in the central dormitory of the university. About six students could live in one room, and I lived with students from different parts of the country. One was from Kunduz. His name was Yusuf, and now he is an official with Jamiat-i Islami. Two others were from Mazar-i Sharif. Some of the students in our room went to the Faculty of Islamic Law, but others attended different schools. . . . There was a mosque on the fourth floor of our hostel. The students who prayed there knew each other well. . . .

(I):In which faculty did the movement first begin, and later on how were relations established with other faculties?

(QA):When the Islamic movement began at the university, it wasn’t started through the efforts of one faculty’s students or teachers. It depended on the feelings, thoughts, and social awareness of everyone who joined the movement. The students who had deeply studied the goals of the communist parties and had the desire to struggle against the regime and the influence of the West and who could think clearly about the future of the country, these people felt a kind of responsibility to form an Islamic movement. It was a matter of feeling responsibility toward Islam for the future of the country. Since the students and teachers of the Islamic law school were studying Islam and knew a lot about it, their feeling of responsibility was stronger than that of others toward Islam and society. For that reason, a greater number of our students and teachers joined the movement and had a more active part than others. . . . Other members were from different schools like engineering, agriculture, medicine, and so on, but still the number of students in the movement from the Faculty of Islamic Law was more than from any other school. At the second level were the students of engineering, medicine, and agriculture. The students from other schools like literature were very few and also dull-minded.

(I):Was there one leader at the beginning?

(QA):The most active student of all was [Abdur Rahim] Niazi. He was among the senior students of the Faculty of Islamic Law, and in 1969 he had the first position in his class. He had a very active role in the movement. He was a leader in all the meetings and demonstrations and all the other activities of the Islamic movement. He was a good speaker, and a spellbinding preacher. His speeches had a strong effect on people, and he was able to attract people through his speaking. He always explained the weak points and defects of communist ideology and their parties. Because Niazi was from the Faculty of Islamic Law, people thought that the movement was limited to there. Some people even called members of the movement “mullas,” so they started to be called by this name. The Khalqis, for instance, always called them “mullas,” but actually the movement was spread throughout the university and involved students and faculty members from different schools.

(I):How did Abdur Rahim Niazi first organize the group? Did he meet with people privately, or did he bring them all together?

(QA):In the beginning, when the demonstrations and meetings of Khalq and Parcham and Shula were first going on, students with Islamic ideas became familiar with each other because they would argue with the communist students. Because of these discussions, the Muslim students came to know which ones had an Islamic ideology and hated communism and other colonialist activities. For instance, I knew Maulavi Habib-ur Rahman because we had graduated from the same madrasa, and we were aware of each other’s ideas and feelings. In the same way, Maulavi Habib-ur Rahman had also spent time with Niazi at Abu Hanifa madrasa—Habib-ur Rahman as a student, and Niazi as a teacher.

They knew very well what everyone’s ideas were, and when Niazi started the movement, he invited the students, like Maulavi Habib-ur Rahman, whom he knew directly and in whom he had confidence. Then, in consultation with them, he chose other students from other schools who were also known to them, such as Engineer Hekmatyar and Saifuddin Nasratyar. They were known to have Islamic thoughts and feelings, and so were some others like Ghulam Rabbani Atesh, Professor [Abd al-Rab Rasul] Sayyaf, Ustad [Muhammad Jan] Ahmadzai, Sayyid Nurullah, and so many others. They were all known as Muslims and anticommunists, so Niazi brought them together and convened the first meeting in Shewaki.

(I):Do you know how many people attended that first meeting and when it was held?

(QA):We were about twenty to twenty-five people, and he discussed the issues and problems that we were facing. He said, “We are working individually everywhere; let’s come together and establish a regular way of working.” All the invited people agreed with him, and then we talked about the plan of how to work.

(I):Do you know the date of that first meeting?

(QA):It was toward the end of 1347 or at the beginning of 1348 [winter/spring 1969], but I don’t remember the exact day and month. . . . When these people came together, they organized groups of five persons each, and they were directed to make that kind of circle [halqa] wherever they found others in whom they had confidence. And they were told to give regular reports of their work to the head [sar halqa] of their circle. . . . Niazi always met with the heads of each of the circles privately, and sometimes they would bring new members to introduce them to Niazi or to have him answer their questions or explain the goals of the movement. He gave answers to their questions about different aspects of Islam, especially economic matters. . . . In private meetings, they trained the members how to discuss and explain their goals. There wasn’t enough time to write brief notes for them, but the members could use the books of famous writers. . . .

Unfortunately, Niazi was alive for just one year after starting the movement. He died in June 1970, so he lived just fourteen months after the beginning of the Muslim Youth Organization (Sazman-i Jawanan-i Musulman). He delivered a total of six speeches during that time—one was at Ningrahar University and another was in Qandahar. He had studied very deeply and was a very eloquent speaker. He had a full command of Pakhtu and Persian and could deliver speeches in both languages. There is no doubt that he was a very knowledgeable and extraordinary man. Every one of his speeches explained some aspect of the movement, like our goals, foreign and domestic policy, the quality and conditions of Islamic ideology. The speeches of other elder brothers of the movement like Maulavi Habib-ur Rahman or Hekmatyar were not equal to his speeches. Every time he spoke, it was like a lesson in theory for the members of the movement. [25]

The most important fact to keep in mind when considering the development of radical Muslim politics in Afghanistan is the place where it all began—the campus of Kabul University. Although originally established in 1946, the university was a small, scattered, and insignificant institution until the mid-1960s, when a major expansion was undertaken that included the consolidation of the formerly dispersed faculties onto a single campus. Bankrolled by large grants from the United States Agency for International Development and other foreign-assistance programs, the university added new classrooms and laboratories, as well as dormitories for the ever-increasing student body, whose numbers rose from eight hundred in 1957, to two thousand in 1963, to thirty-three hundred in 1966. Along with the infusion of money, students, and facilities came foreign instructors from the United States, Europe, and the Soviet Union.

The most significant feature of the university, however, was not that it brought Afghans together with foreigners but that it brought Afghans face-to-face with each other. Never before had there been an opportunity for so many young Afghans to interact over an extended period of time with other young Afghans from different regions of the country. Despite efforts by rulers like Abdur Rahman to convince citizens that their primary identity was as subjects of the state, Afghanistan had remained a patchwork of disparate tribes, regions, sects, and language groups that was held together, at times rather flimsily, by strong men at its center and foreign enemies along its borders. The one institution that consistently worked to mitigate and blur the boundaries between groups was the army, but since many of the army units retained a tribal and ethnic cast and most soldiers were illiterate and poor, the influence of this institution was limited.

The university, however, brought together students from all over the country. Entrance to the university was difficult. A large number of students were from the elite—not all of whom deserved or desired to be in university—but many others made their way to the campus by dint of their own achievements in provincial secondary schools. And those who did make it were rewarded not just with an education and the prospect of a life lived outside the village but also with the prospect of being an instrumental part of the nation’s development. Never before had Kabul been so flush with funds. Never before had so much building been undertaken for the benefit of ordinary people. This munificence helped to inculcate in the students a sense of their own importance. So too did the fact that they had been dropped down in this exciting new place at a moment in the nation’s history—the period of the “new democracy”—when it appeared that just about anything was possible. These were exciting times, and it seemed to the students that they themselves were one of the things that was most exciting about it. That, anyway, was the perception. The reality, not surprisingly, was different.

In Heroes of the Age, I discussed the importance of location in the success of Sufi orders in the late nineteenth century. The Mulla of Hadda, as well as most of his principal deputies, situated their centers in areas interstitial to tribes and the state. Hadda itself was a barren area between the provincial capital of Jalalabad and the mountain fastness where the Shinwari, Khogiani, and other tribes made their homes. Most of the Mulla’s deputies set themselves up in villages in the Kunar Valley, where they were accessible to but not dependent on their tribal disciples, who were living in the mountains lining both sides of the valley. Interstitiality was equally important for the development of radical politics in the contemporary era, but in this case that interstitiality was located at the university campus.

Students from rural areas, who were accustomed to hearing only their native language spoken and to dealing primarily with kinsmen and others they had known their whole lives, were suddenly placed in tight quarters with people from different ethnic and linguistic groups. Most of the students were serious and valued the opportunity to be at the university, but a number had gotten into the university through family connections, and they had no interest in studying. Some of these students spent their time gambling and smoking hashish—which was less expensive and more readily available than alcohol—and in extreme cases students who didn’t want to attend a course on a given day coerced others into staying away, so the professor had to cancel the class.

The two places where tensions ran highest were the cafeteria and dormitories, both of which were severely overcrowded. Endless lines formed at meals, and students with reputations as tough guys cut into lines. Dormitories had only a few showers, and hot water was available for only a few hours during the day, so students had to sign up ahead of time for showers. Here again, some students abused their rights, daring the student who lost his place to protest. Many of these tough students were known to carry knives; one informant told me of witnessing a knife-wielding bully chase another student through the dormitory into the fourth-floor mosque, where other students were praying, and stabbing him in the shoulder. School administrators generally kept their distance in these situations, in part at least because some of the worst violators of school rules were the sons of well-connected men whom the administrators could not afford to offend. [26]

If, as I argued in Heroes of the Age, becoming a disciple of a Sufi pir was for some a response to the heartlessness of the tribal world, joining a political party was for students to some degree an antidote to the friendlessness and anarchy of the university. Students who were even moderately inclined to religious feeling, who had prayed regularly at home and wanted to continue this practice at university, were impelled to seek the company of likeminded students not only because of the corruption and abuse they saw around them but also because of the petty annoyances of leftist students who reportedly took great pleasure in making fun of the customs of the devout. Niazi and other founding members of the Muslim Youth offered a bulwark against what appeared in the concentrated atmosphere of the university to be a tidal wave of atheistic behavior. Niazi, intelligent and charismatic, held daily meetings after prayers, during which he discussed with younger students sections of the Qur’an and hadith and helped them interpret the significance of these passages in light of current events. Initially, these meetings did not have a specific political content and were not sustained by any organizational apparatus. When campus elections were held, Muslim students at first did not have a specific party affiliation, referring to themselves rather as bi-taraf, or “nonaligned,” but eventually the members of this group, recognizing their common interest in Islam, joined together as Sazman-i Jawanan-i Musulman—the Organization of Muslim Youth.

Accounts of the origins of the Muslim Youth Organization differ depending on the political affiliation of the speaker, but it is generally accepted that Muslim students began to meet on the campus of Kabul University in 1966 or 1967 and that a group of students representing different faculties within the university formally established the Muslim Youth Organization in 1969. The founding members of the Muslim Youth were initially inspired by a group of professors in the Faculty of Theology, most importantly Ghulam Muhammad Niazi (not a relative of Abdur Rahim Niazi, though both were from the Niazi tribe), who had studied in Cairo in the 1950s and had come in contact with members of the Muslim Brotherhood during his stay there. Although Ghulam Muhammad Niazi and other professors did not take a direct role in student activities, they informed the students of movements going on in other parts of the Muslim world and provided them with a sense of how Islam could be made relevant to the social and political transformations everywhere apparent in the latter half of the twentieth century. [27]

This was an important requirement for many of the students, for as heady as it was to be at Kabul University during this period, it was also disorienting. Many of the students had never been far from their native villages before their arrival at the university, and for most of their lives Kabul itself had been little more than a distant rumor and a radio signal. In this context, many of the old ways—the customs and traditions that had bound together the villages from which most of them sprang—lost their vitality and their basic viability. What had given structure and meaning in the local community—the centrality of the kin group, the respect due senior agnates, the rivalry between cousins, the informality and warmth of the maternal hearth—were irrelevant in the university setting, where unrelated young people came together unannounced and unaware. In its earliest days, the Muslim Youth can be seen as a response to the experience of disorientation. In the beehive of a dormitory with twenty-five hundred denizens, groups of students sharing common interests began to gravitate to one another, and their association with one another helped stave off the loneliness and alienation that attended being strangers in a strange land. Significantly, the list of the founding members of the party included an even mix of Pakhtuns and Tajiks from a variety of provinces. Most of the students were Sunni, but there were a few Shi’a members as well, and this demographic mix speaks to the relative egalitarianism of the movement at this point as well as to its inclusiveness, both elements that would be lost as time went on.

In his life history of a religious scholar in Morocco, Dale Eickelman points out that some of the most significant educational experiences of his subject occurred outside the classroom in the peer learning circles that students formed among themselves. [28] The same could be said of Qazi Amin, and when I spoke with his contemporaries, the experiences they tended to emphasize as most memorable were also those they had in the company of their peers. [29] Even the stories of leftist provocation were told with a certain relish; it was clear that these incidents, which were recounted to indicate the immorality of the enemy, also were recalled with a sense of nostalgia. These provocations brought the movement into being, generated that first sense of righteous indignation and purposefulness, and led to a feeling of communal solidarity that the students had never felt before and that they had rarely felt since. [30]

Confrontation, Armed Conflict, and Exile, 1969–1978

(I):Do you remember any particular events from that period that you were involved in? Are there any clashes or demonstrations or other specific memories that you recall?